Delphi Technique: Predicting Emerging Opportunities and Challenges in Renewable Energy

3 | Designing and Planning for Delphi

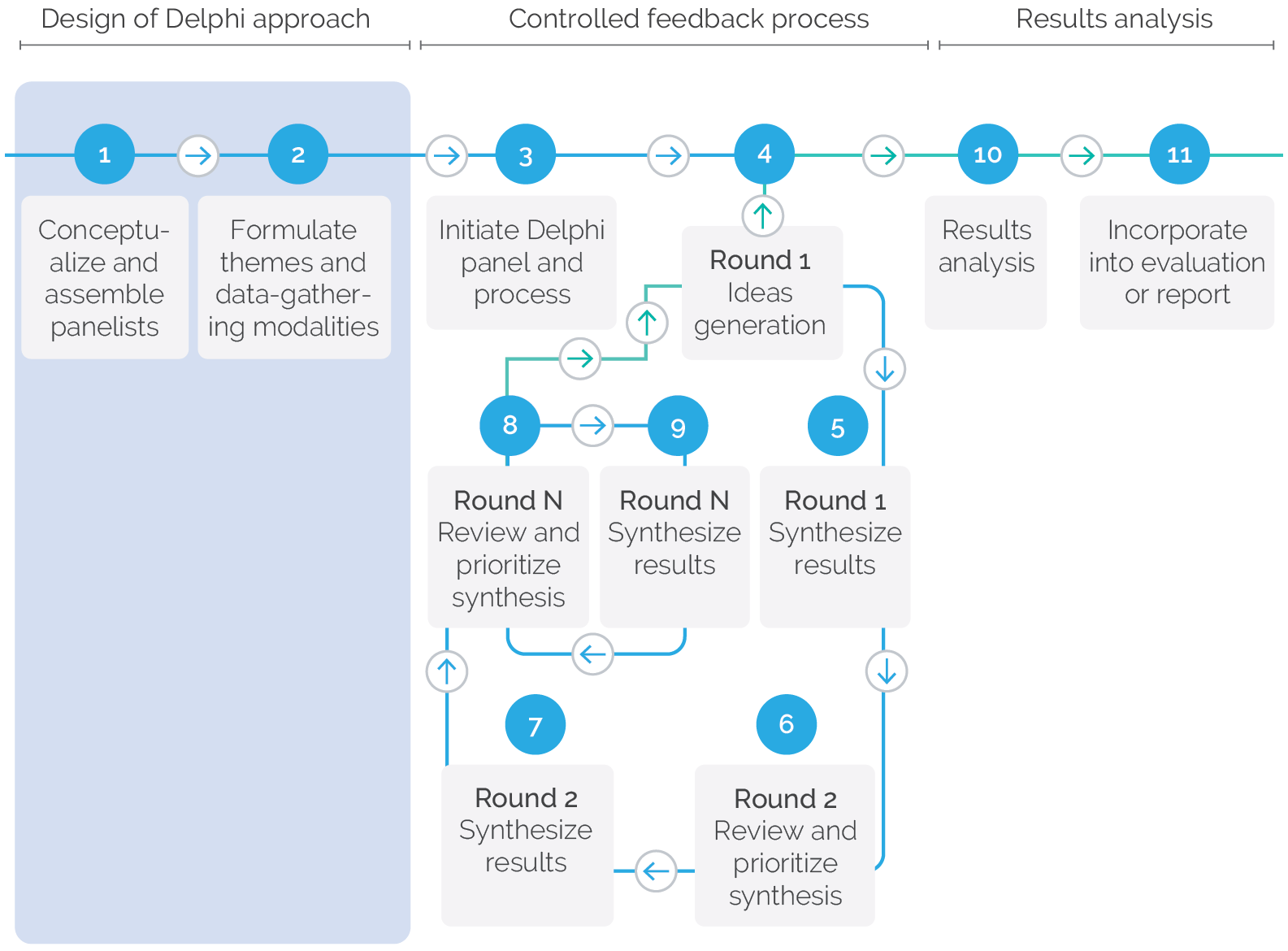

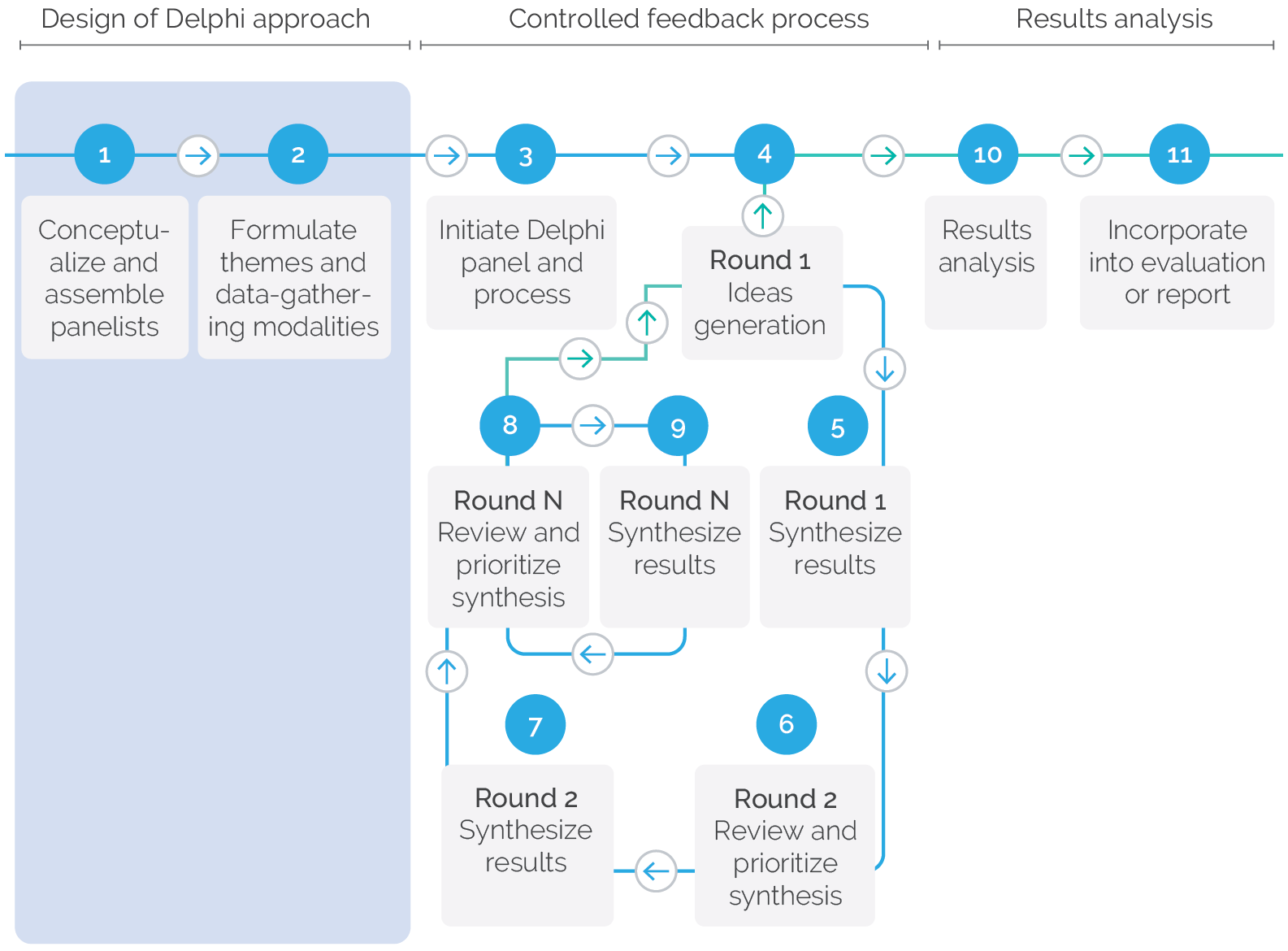

The successful application of a Delphi technique requires careful design and planning, a tightly administered feedback process, and robust analysis of results to formulate conclusions. The illustration in figure 3.1 diagrams the key steps to completing a Delphi process.

Figure 3.1. The Delphi Process—Design Stage

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

This section focuses on the first stage of applying a Delphi process (highlighted in blue in figure 3.1), which is to design and plan the approach. The aim is to develop the strategy and the preparatory steps needed to effectively capture feedback from experts and analyze the results. The specific approach that was applied in the RE evaluation is detailed for each step.

Conceptualize the Delphi Process

Conceptualizing the Delphi process requires rationalizing the purpose of using a Delphi process with a panel of experts and how the results would be used, whether in a stand-alone manner or as a part of a multimethod evaluation, as was the case with the RE evaluation (figure 3.1, 1). It is also useful to consider the time frame and budget needed to carry out the Delphi activities.

In the RE evaluation, the Delphi technique was selected as a key method specifically to help frame the responses to a key evaluation question: What lessons from experience can be identified to strengthen the role of the Bank Group in helping clients achieve their emerging RE goals (that is, scale up for meeting SDGs and the clean energy transition)? To answer this question, more than an assessment of the Bank Group’s capacity and position of influence was needed; it required a prediction of the investment climate that would prevail in developing country RE markets in the coming years. The decision by IEG to assemble a global panel of experts on RE and lead them through a Delphi process was an essential element of making such a forecast. It would help determine the Bank Group’s readiness to help clients navigate future RE markets based on its capacity assessed against the predictions of the Delphi panel. The findings from the Delphi process could then help draw conclusions when triangulated with results from other methods, such as a qualitative comparative analysis (QCA), a project portfolio review, and interviews with Bank Group staff and developing country stakeholders.

Administering a Delphi panel also fit within the schedule of the overall RE evaluation. Although the Delphi approach was conceptualized early in the process of preparing the overall RE evaluation, most of the other methods were already underway by the time IEG assembled the global panel of experts in RE. It was anticipated that the Delphi approach could be completed in two to three iterative rounds before the results could be analyzed for incorporating into the RE evaluation. The anticipated costs were also budgeted, including payments for panel members and expenses for administering the Delphi process.

Assemble Panel of Experts

The identification of suitable panelists (figure 3.1, 1) is a critical element to the successful application of a Delphi process, since the results crucially rest on the panel. It is vital to include specialists who have strong reputations with regard to their expertise on the subject matter. This may be straightforward when exploring a narrow subject with well-understood industry norms. Appropriate representation can be more complex when the subject is broader (possibly at the congruence of multiple subjects, such as climate change) or less well defined. The size of panels ranges widely based on Delphi-related literature; some are more akin to smaller focus groups, and others can be large and almost surveylike. A consideration for smaller groups is ensuring that there are not significant dropouts over the multiple rounds, as this may compromise the integrity of the results. With very large groups, it may be asked whether the highest level of expertise on the subject is so widely dispersed.

The RE evaluation was exploring the sector at the energy and environment nexus as a key solution to sustainably meeting energy demand and helping mitigate global climate change. This made the subject matter wider than delving into the narrower area of RE, requiring broader expertise within the Delphi panel to provide a global environmental perspective. Therefore, several overarching criteria were applied when inviting experts to participate in IEG’s global expert panel on RE:

- Extensive knowledge, applied experience, and globally recognized expertise in issues of energy, climate change, or both.

- A mix of representation within the panel from developed countries, where much RE development has occurred, and developing countries, which represent the lion’s share of future expansion (and make up the Bank Group’s clients).

- A combination within the panel of experts in private sector development of RE, which is expected to make a significant contribution to the clean energy transition, and those with deep knowledge of public sector initiatives in policy and investments, which are likely to be important in facilitating the expansion of RE in developing countries.

- Experience addressing climate change at the global level and an understanding of the implications for it of scaling up RE.

The aim was not to be dogmatic about the criteria but to ensure that the overall global panel of experts on RE would adequately represent these important considerations, so that panelists would take into account a diversity of perspectives related to RE in arriving at conclusions. Ultimately, IEG’s global panel of experts on RE included eight members. The panelists were from developing and developed countries, representing both the public and private sectors. The private sector was represented by a RE investor in emerging markets and the leader of a global RE equipment manufacturer. Large developing countries with a significant global environmental footprint and ambitious RE targets, such as China and India, were represented, as were smaller, less polluting countries at different stages on the development spectrum. Several experts from globally significant carbon dioxide (CO2) emitters and from those countries most urgently affected by climate change participated in the panel. Each of them had played a prominent role in the Paris Agreement negotiations. Some experts also represented global think tanks on energy and academia. One shortcoming in the panel was gender balance. Despite efforts by IEG, some invited female participants declined because of scheduling difficulties, and in one case, a possible conflict of interest. Perhaps inviting more female panelists earlier in the process would have resulted in better gender balance.

Formulate Key Themes and Questions

Based on the conceptualization, determine what themes the panel of experts is expected to explore through the Delphi process (figure 3.1, 2). Once the themes are selected, it will be important to carefully craft the specific questions posed to the panel, ensuring that they are clearly formulated to prevent ambiguous interpretations. Jargon that might be variously interpreted should be clarified or entirely avoided, but commonly understood industry terminology is appropriate.

In the RE evaluation, the objective was to explore in greater depth certain aspects of the theory of change (ToC) that were developed by IEG based on global (including Bank Group) experience. The ToC, elements of which are described in more detail in box 3.1, was predicated on investments in RE resulting in (i) benefits to consumers from the increase in electricity supplied, and (ii) contributions to mitigating global climate change stemming from the displacement of alternative fossil-based power generation sources that would have otherwise emitted CO2 (a causal link that was subsequently confirmed through a separate QCA). However, mobilizing investments in RE can be hindered by several key barriers, according to the ToC. Therefore, adequately addressing these barriers was vital to achieving the energy and climate goals. The dynamic evolution of RE markets over the evaluation period also changed the nature of these barriers to RE, while other opportunities for scaling up various technologies emerged. Similar market shifts are expected to continue and change the future investment landscape in the sector. Through IEG’s global expert panel on RE, the RE evaluation sought to identify these future changes in RE markets that may help or hinder the envisaged scale-up in the sector by proposing the following questions:

- What are the main emerging opportunities to further develop RE around the developing world for power generation to meet climate and SDGs (and why)? An opportunity was defined as a specific condition that is favorable or conducive to scaling up RE per the clean energy transition, including but not limited to technological advances, improving market conditions, changes in demand patterns, shifts in policy, and influences outside the RE space (such as shifts in fossil fuel prices or the impact of climate change).

- What are the main emerging challenges that could hold back developing countries from further development of RE for power generation, and hamper their ability to meet climate and SDGs (and why)? A challenge was defined as a specific constraint or barrier that countries are likely to face in attempting to scale up RE per the clean energy transition, which, if not addressed, will hamper their ability to achieve RE development goals.

- For the emerging opportunities and challenges that are predicted by the respective panelist, what specific key action(s) should be taken by developing countries to seize each opportunity and address each challenge? The aim was to solicit potential solutions that could be implemented by developing countries.

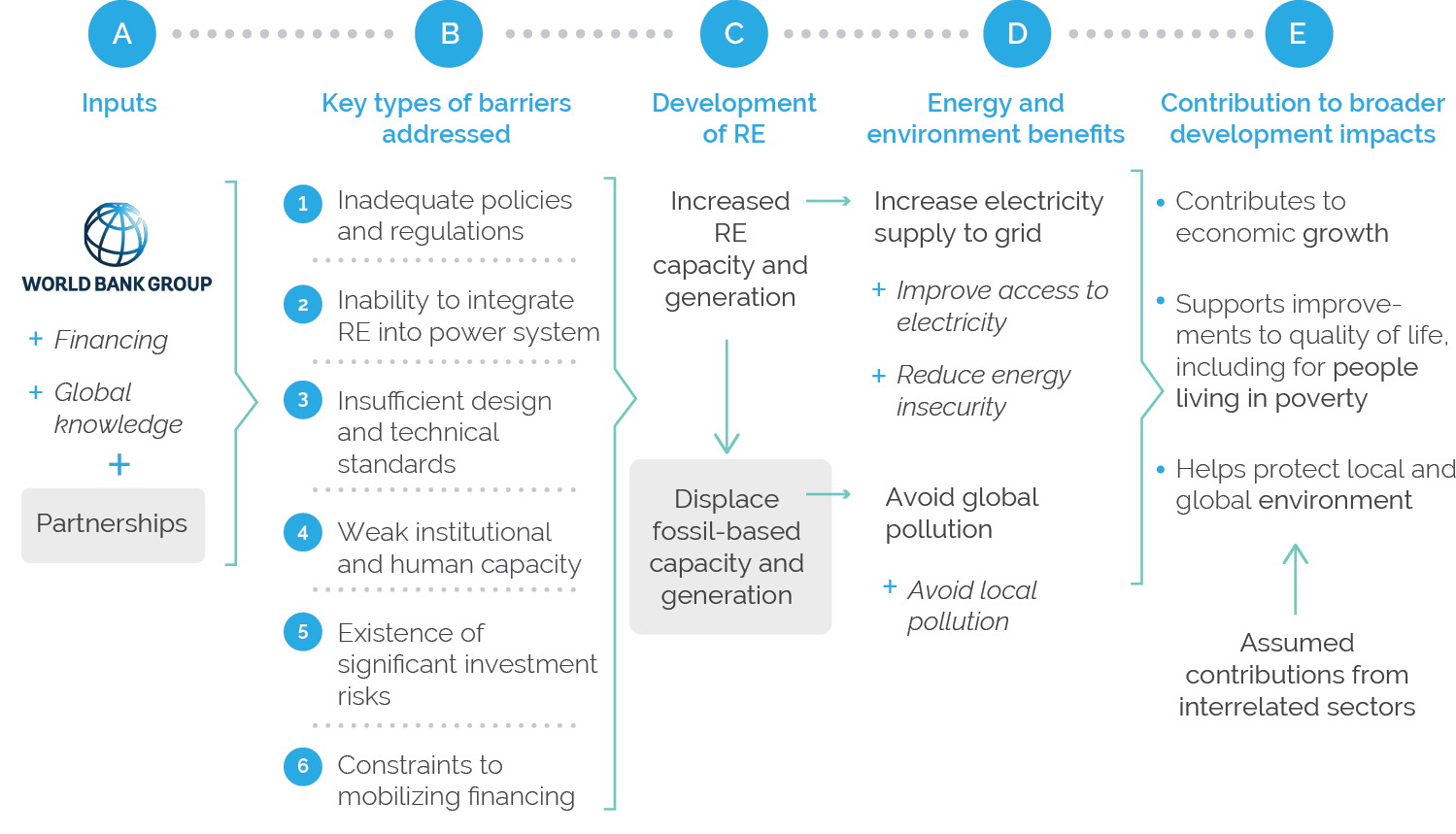

Box 3.1. Theory of Change for RE Evaluation

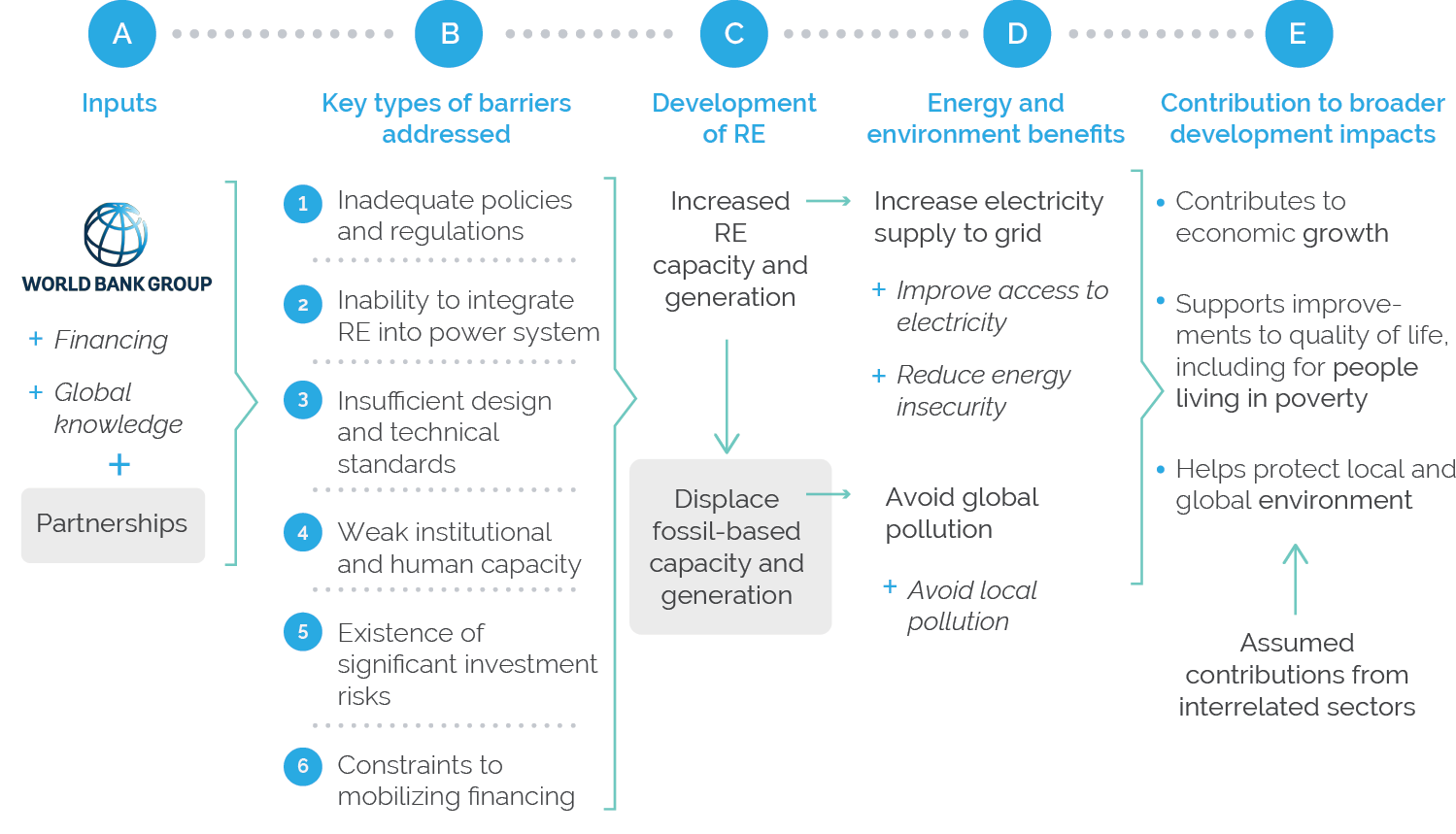

The following theory of change (ToC) was developed by the Independent Evaluation Group to define the causal relationship for expanding renewable energy (RE), incorporating the World Bank Group’s role in supporting clients achieve their energy and environmental goals.

Figure B3.1.1. Theory of Change for Renewable Energy Development

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: RE = renewable energy.

The ToC is most easily understood beginning with the column labeled C, which depicts an output of increasing investments in RE technologies, which essentially means the construction and operation of RE power plants and associated infrastructure such as transmission lines to evacuate the electricity for supplying consumers (that is, to load centers). Column C also illustrates that investments in power generation from renewable sources lead to the displacement of an equivalent amount of alternative generation capacity from fossil fuels.

Column D identifies the outcomes that result from this increase in investments in RE and the displacement of fossil-based power generation. The primary energy benefits are accrued to grid-based consumers from the increase in supply as a result of RE-based power generation. Additionally, RE-based electricity can also help increase access to those who currently are not connected; and, as indigenous resources, RE-based electricity can reduce energy insecurity that arises from greater reliance on fossil fuel imports. The environmental benefits are derived from the displacement of fossil fuel–based generation by RE, which helps curtail carbon dioxide greenhouse gases that would have been otherwise emitted, contributing to global climate change (that is, avoided global pollution). Additionally, the displacement of fossil fuels also helps avoid local pollution from the emission of sulfur oxide, nitrogen oxide, and particulate matter, which can lead to respiratory illnesses and other health impacts. Column E illustrates how the energy and environmental outcomes, interdependently with outcomes from other development efforts, contribute to larger development impacts.

Although mobilizing investments in RE, as depicted in column C, is a major contributor to meeting energy needs while protecting the environment, the ToC suggests that this is dependent on adequately addressing several major barriers that affect the investment climate for RE, as illustrated in column B. The ToC also suggests that a major contribution of the Bank Group to expanding RE is to help clients address these key barriers through disseminating global knowledge, extending financing, and mobilizing partnership support using its global convening capacity, as illustrated in column A.

Members of the Independent Evaluation Group’s global panel of experts on RE were requested to share their expertise, primarily on addressing barriers to RE development (column B) and the World Bank’s readiness to support clients in this effort (column A), although they were free to comment on any aspect of the ToC.

The previously mentioned themes aimed to elicit perspectives on the energy sectors in developing countries, irrespective of the involvement of the Bank Group. They reflect challenges that must be overcome by countries seeking to scale up RE, opportunities they could seize to do so, and the actionable solutions they could undertake toward these ends. However, IEG also wanted to explore the extent to which the Bank Group can support clients in successfully implementing these actions or solutions identified by the global panel of experts on RE. It was recognized that, although the panelists were sector experts who were aware of the Bank Group’s global role in supporting RE, their knowledge regarding the institution could vary across the panel. However, when triangulated with evidence from other methodological sources, expert perspectives could provide meaningful insights into the readiness of the Bank Group to help clients navigate future RE markets that continue to evolve. Therefore, IEG’s global panel of experts on RE was asked to assess, for each of the actions or solutions identified (for addressing challenges and seizing opportunities), the Bank Group’s position to influence and capacity to help clients:

- Identify how well the World Bank Group is positioned to help clients to successfully carry out [each] action/solution. The aim was to identify the institution’s sphere of influence and the corresponding comparative advantage to support clients in implementing reforms, recognizing that there are other actors that can shape actions, including the clients themselves.

- Identify specific interventions/engagements the World Bank Group can take to support clients more successfully implement each respective action/solution. The Bank Group could support clients in a range of ways that include sharing of global experiences and knowledge transfer, financial support, and mobilizing additional support from other partners based on the institution’s global convening capacity.

- Identify the current capacity of the World Bank Group to successfully undertake each intervention/engagement for supporting client actions/solutions. The aim was to identify whether the institution has the expertise and experience to adequately help clients undertake their specific actions or solutions for scaling up RE.

Design Data Gathering Modalities

Once the questions are clearly defined, the next key step is to determine how the feedback from panelists will be gathered (figure 3.1, 2). Typically, a questionnaire or template is prepared, which can be administered electronically or on paper. It is at this stage that the designers of the Delphi process will determine the structure through which panelists will prioritize or score various inputs and how these results will be (statistically) evaluated to form conclusions. Panelists’ familiarity with different technological modalities is a consideration when designing feedback questionnaires or templates, as is the simplicity and ease with which they can respond to others.

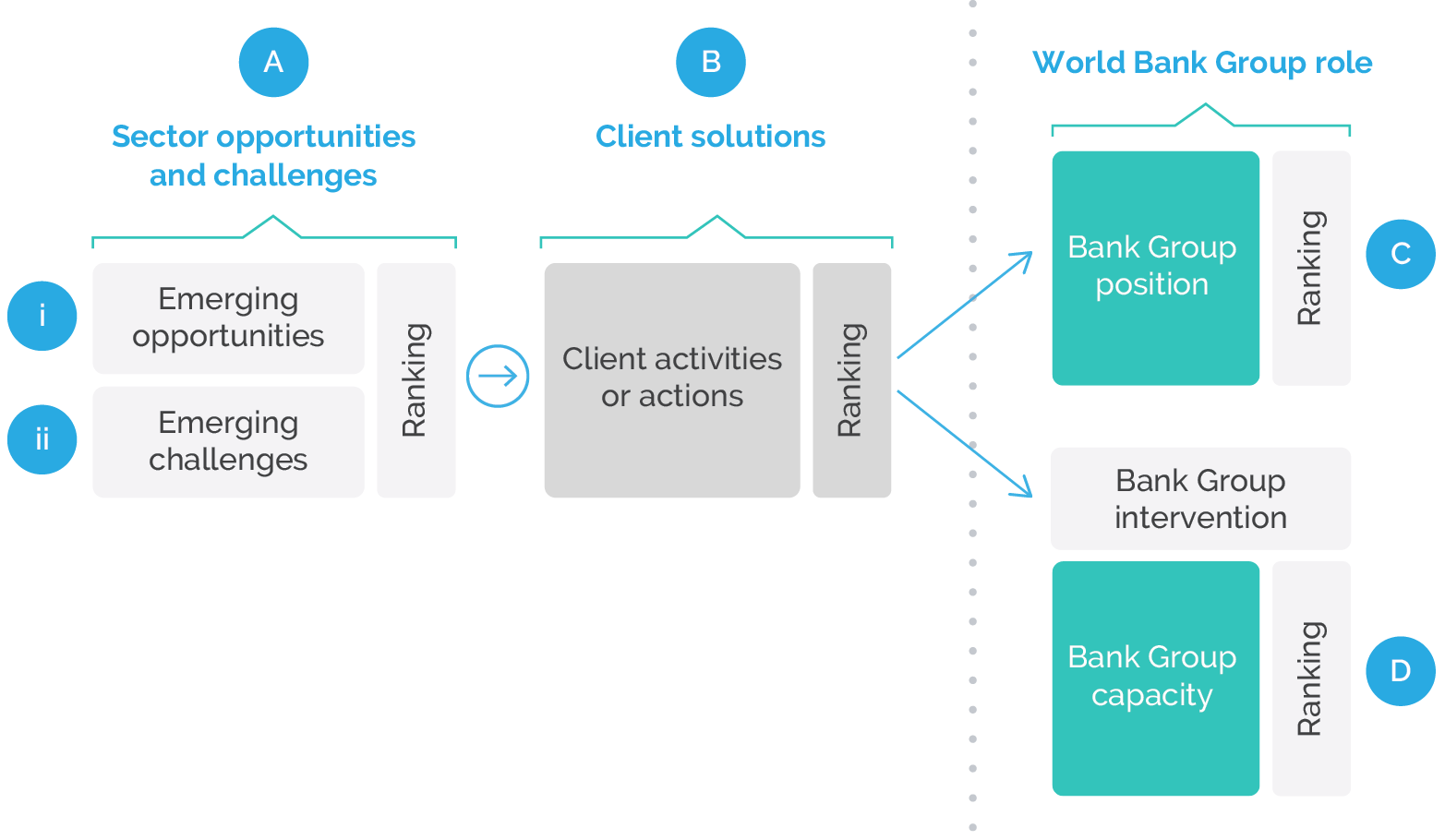

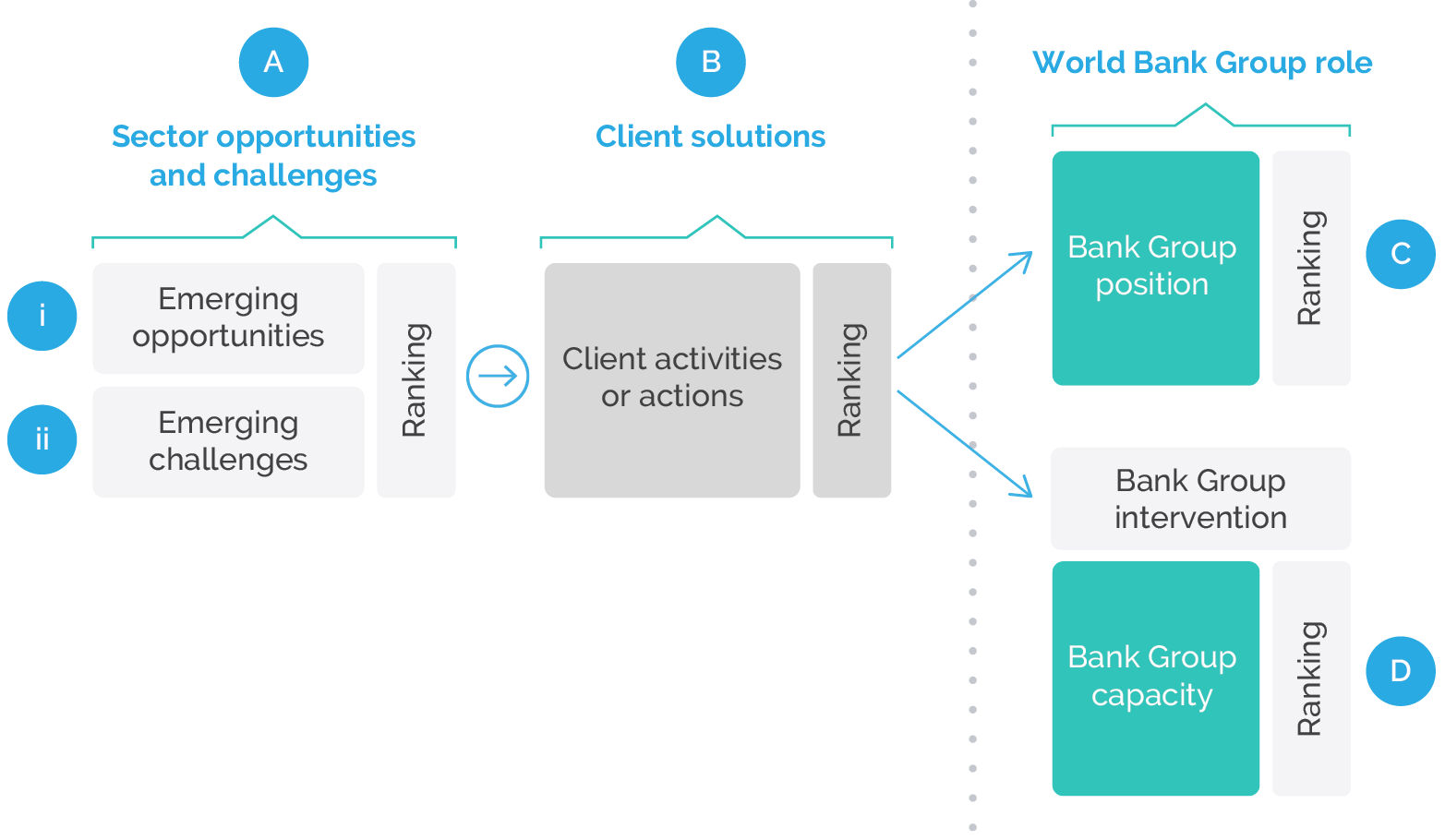

In the RE evaluation, the questionnaire was formulated as a Microsoft Word template, given a diverse international panel’s likely familiarity with that software. An option to develop a web-based interface was discussed and discarded, as such a prototype was not needed and the effort to manage such feedback from a relatively small panel could not be justified. The template that was created played an important role in maintaining control and structure in obtaining feedback, so that results were comparable and could be aggregated with consistency. Two templates were used, one to capture perspectives on emerging opportunities and the other to solicit views on challenges facing the scale-up of RE (figure 3.2, i and ii). The blank templates used for the information initially gathered from IEG’s global expert panel on RE are presented in appendix B. Figure 3.2 also highlights the main structure of each of the two templates, emphasizing the areas where expert opinions were solicited from the panel, consistent with the themes identified in the previous section.

Figure 3.2. Structure of Feedback Template

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

- Identify specific opportunities or challenges facing the expansion of RE, including rationale for the significance of the selection (figure 3.2, A). The panelists were also requested to provide a score ranking for each selection to ascertain their initial prioritization. The responses were open ended, although each panelist was restricted to a maximum of 10 opportunities and 10 challenges, to maintain a sense of priority.

- For each of the opportunities and challenges identified, indicate up to three actions or solutions developing countries could undertake to expand RE (figure 3.2, B). Ideas for actions or solutions were only solicited at the initial stage, and later stages requested the panelists to prioritize actions or solutions.

- The remainder of the templates focused on the Bank Group’s readiness to support clients in undertaking their respective actions or solutions identified by panelists for each opportunity or challenge. This included obtaining expert opinions on how well the institution is positioned or placed, especially when compared with other development partners, to influence the changes identified as actions or solutions (figure 3.2, C). The panelists were asked to score the strength of the institution’s place or position to undertake each intervention.

- The templates also solicited up to three specific potential Bank Group interventions or support that could help clients successfully undertake their respective actions or solutions.

- For the same actions or solutions, panelists were requested to provide their views on the Bank Group’s existing capacity to help client countries successfully design and implement such actions or solutions through specific interventions (figure 3.2, D). The capacity could include a combination of the institution’s skills and experience, and ability to convene and influence stakeholders and extend financial support. The panelists were asked to score the institution’s level of capacity to undertake each intervention.