Findings: IFC’s Investments and Advisory Services in FCS

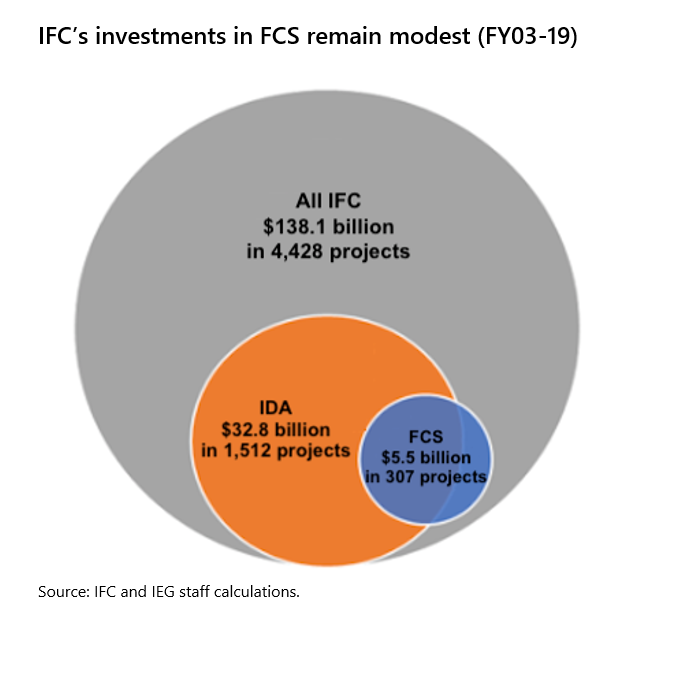

IFC ’s investment volume in FCS has been modest and has not shown an increasing trend over the last decade. In FY10-19, long-term investments reached 4.5 percent of its total new commitments and 7.5 percent of the number of projects. IFC’s portfolio in FCS countries is diversified across industry groups.

Advisory services are a key modality for IFC’s engagement in FCS. They are more highly concentrated in FCS compared to its investments; FCS account for 16 percent of advisory projects and 14 percent of project expenditures (both numbers exclude regional advisory services projects).

More findings related to IFC’s Engagement in FCS since 2003 (Chapter 2)

Findings: Results of IFC in FCS

Evaluated IFC investment projects in FCS perform similarly to those in non-FCS: 54 percent of projects in FCS countries are rated mostly successful or above for their development outcome, compared with 58 percent for projects in non-FCS countries. These results indicate that it is feasible to implement developmentally and financially successful projects in complex and risky FCS environments (see Chart).

These results also reflect IFC’s current business model, approach and policy and risk parameters, which may, however, also constrain IFC’s ability to scale up business in FCS as the flat business commitment volumes in FCS countries since fiscal year 2010 suggest.

Evaluated investments have a range of positive development outcomes in their FCS host countries, including increased employment and income-earning opportunities, upstream and downstream linkages with local businesses, the generation of government revenues, lower consumer prices, and increased access to infrastructure and services. Evaluations observed that IFC’s due diligence standards have generally been high and did not find any significant adverse effects on local communities or private sector development in FCS.

By industry group, projects in telecom and infrastructure and natural resources performed well, while manufacturing, agribusiness and services projects faced challenges in meeting their financial and development objectives.

Stronger results among evaluated investments were associated with larger investment sizes and larger economies – characteristics that may be limited in FCS countries and may constrain scaling up IFC engagement in the future. In some cases, inherent risks related to fragility and conflict such as security risks adversely affected project performance. IFC worked with strong and sophisticated clients in FCS, which likely supported positive outcomes and helped mitigate country risks. However, the focus on stronger clients may also indicate a degree of risk aversion to work with new types of clients.

The quality of IFC’s own work in appraising and supervising its investments in FCS was strong. IEG has consistently found that work quality is strongly associated with development outcome ratings. This analysis also indicates that there is a higher potential payoff from strong work quality in higher-risk markets such as FCS.

An initial IEG review of IFC’s use of blended finance suggests the instrument can help support projects with high financial risk perceptions but it does not provide significant risk reduction in non-financial risk areas.

Evaluated IFC advisory services interventions in FCS performed below those in non-FCS countries. Forty-seven percent of advisory services interventions achieved mostly successful ratings or above for their development effectiveness compared with 56 percent in non-FCS. Several projects highlighted the importance of capacity building and absorptive capacity in FCS. Regarding assistance to investment climate reform, IEG evaluations conclude that reforming business environments is a necessary condition in the medium term but not sufficient to overcome constraints to private investment in FCS.

Lessons

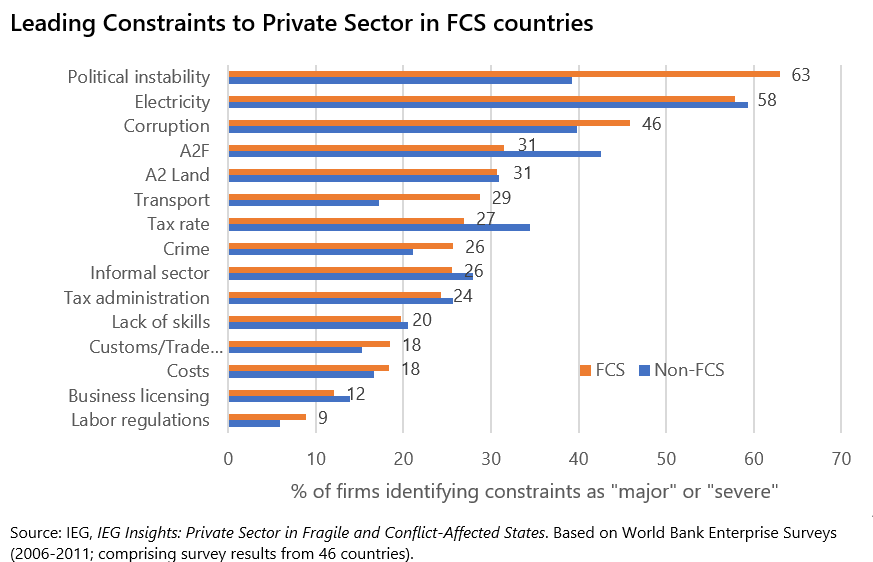

Promoting private sector development and private investment in high-risk FCS remains a major challenge. IEG evaluations emphasize the challenges related to leveraging the private sector for sustainable development in FCS countries, including investing in difficult operating environments with specific fragility risks (such as security, weak capacity of clients and governments), different characteristics of the private sectors and potential project sponsors, distinct features of investment opportunities, and higher cost of doing business. A key knowledge gap remains concerning which approaches and instruments are effective in engaging the private sector in FCS countries.

IEG evaluations suggest several lessons for IFC in engaging in FCS:

Adapting IFC’s business model, instrument mix and risk tolerances to FCS countries and to the characteristics and needs of the private sectors in such countries can help scale up business opportunities for IFC. IFC has adjusted its strategy and introduced several new mechanisms and instruments to support business in FCS. However, it has not systematically adapted its business model to work in FCS.

Similarly, aligning internal incentives and performance metrics to IFC’s strategic objectives can support increased engagement in FCS. To this end, IFC recently added corporate targets and metrics for its commitments in FCS and low-income countries in its corporate scorecard and redesigned its corporate awards program. IFC can further link its corporate goals to individual performance metrics. Finally, past evaluations point to the importance of adequate staffing for FCS. These evaluations also found that IFC has deployed relatively few investment officers to FCS.

The range of potential private sponsors in FCS countries suggests different pathways to increasing business in FCS – including through proactive upstream efforts to conceive projects, working with existing clients not yet invested in FCS, and engaging with non-traditional sponsors.

Given the low capacity of firms in many FCS, advisory services may be important to enhance the capacity of some clients.

IFC can have high additionality when it is working with smaller domestic sponsors or existing clients investing in an FCS for the first time. Its implied political risk insurance and implementation support helped enable several investments in FCS. In some cases, however, additionality was more limited where an established client may have been able to attract similar financing from commercial sources.

Nobody can do it alone. Engaging with the private sector in FCS countries requires collaboration and offers opportunities for synergies among World Bank Group institutions. Collaboration among WBG institutions facilitated private sector investment in high-risk countries.

More lessons from IFC’s Experience in FCS (Chapter 4)

Past IEG evaluations have identified the following three areas of attention that can potentially strengthen IFC’s engagement and support the scale-up of its investment and advisory activities in FCS countries:

- Tailor business development to different typologies of FCS markets and different types of potential private sector clients in FCS countries;

- Address IFC staff incentives, skills, and staffing to enhance their ‘fit for purpose’ to FCS-related work;

- Adapt IFC’s approach, risk appetite, instruments, and metrics of success to the context of FCS countries.

More implications for IFC’s Work in FCS and for Future Evaluation (Chapter 5)