Delphi Technique: Predicting Emerging Opportunities and Challenges in Renewable Energy

5 | Analyzing Results

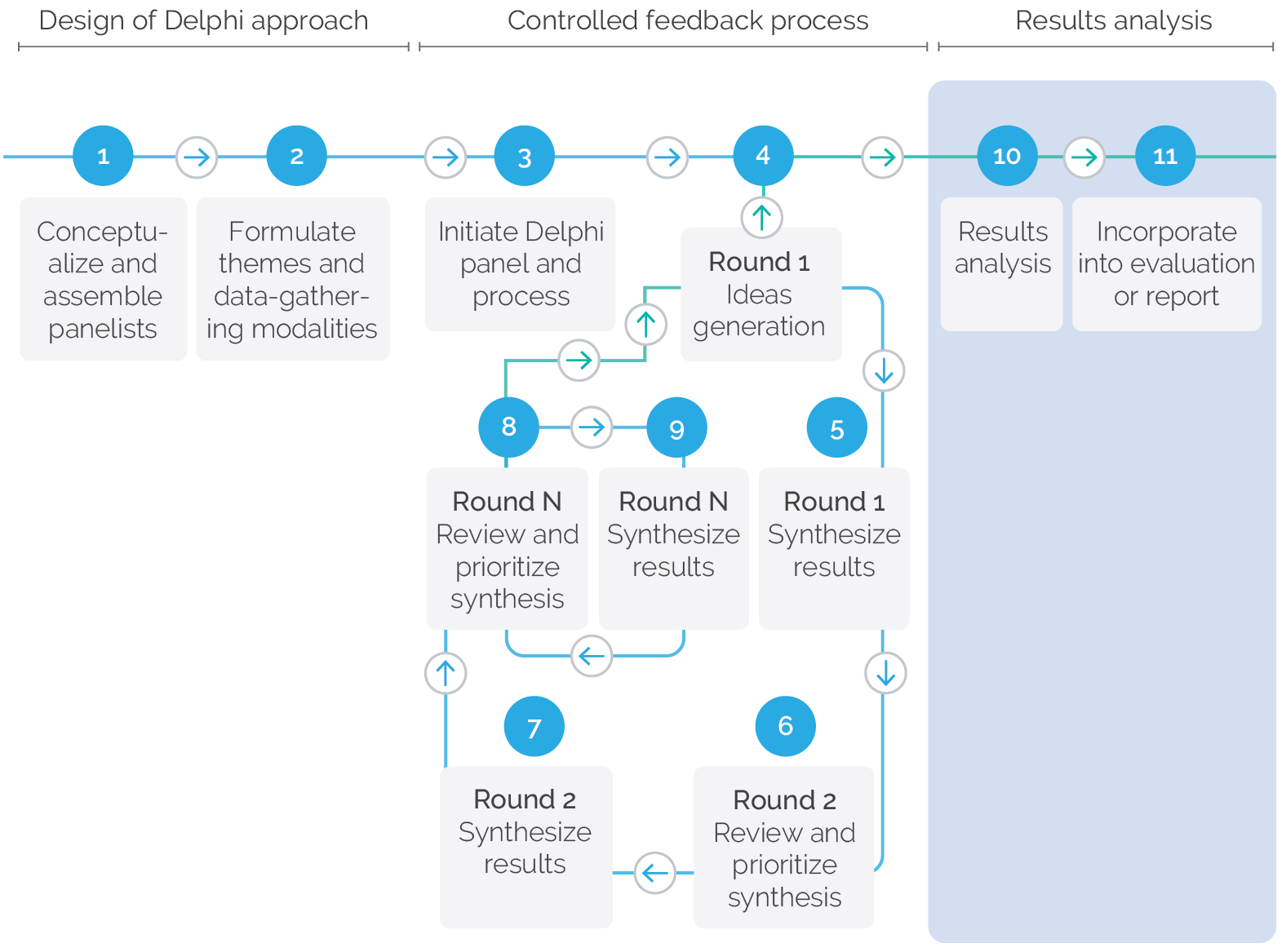

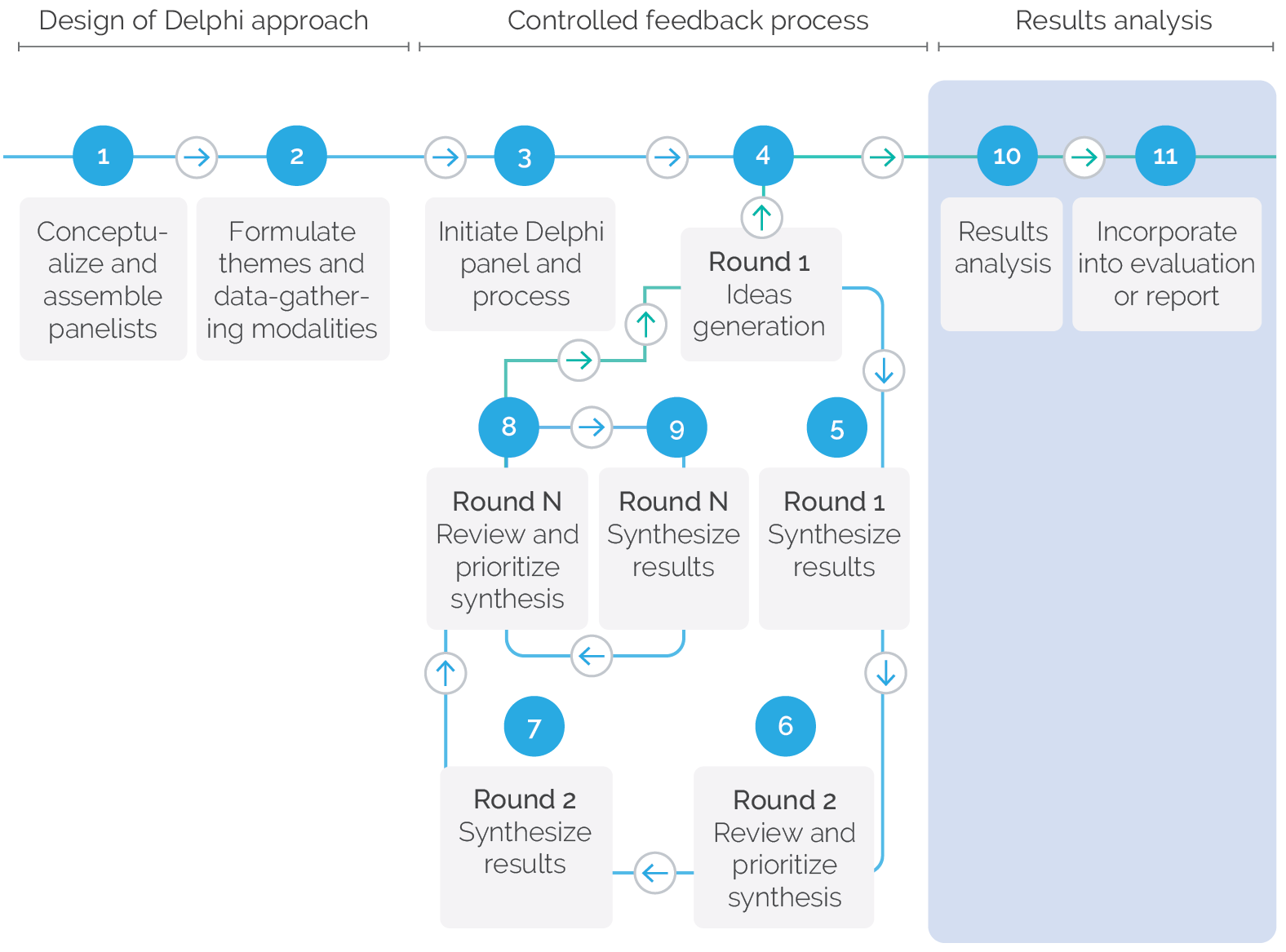

The third and final stage is to analyze results from the Delphi process and triangulate them with other methods in the RE evaluation to draw conclusions. This chapter focuses on analyzing the results, and chapter 6 describes what conclusions were drawn from the results and how they were integrated into the broader RE evaluation. Greater subject matter focus was provided, given that the results needed to be analyzed using an energy sector perspective. At this stage, no further iterations nor participation by the panelists are required except to seek specific clarifications regarding their responses as needed. The analysis is carried out by the team administering the Delphi process. The Delphi process step covered in this chapter is marked 10 in the blue-highlighted area in figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1. The Delphi Process—Results Analysis Stage

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Analyze Results to Extract Key Findings

The ideas generated and the data on prioritizing these opinions can now be summarized, represented visually, and analyzed statistically to draw key conclusions from the Delphi exercise (figure 5.1, 10). This can be typically carried out using spreadsheet and other data analysis software. Subject matter expertise and a basic understanding of statistics are important at this stage of the process to formulate robust conclusions.

In the RE evaluation, a combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches was used to analyze results. Basic data analytics or statistics were used to calculate the average (mean) scores to rank priorities collectively for the panel and standard deviations from the mean to ascertain the degree to which panelists reached consensus related to specific responses. The qualitative interpretation and contextualization beyond statistical measures relied heavily on sector expertise within the evaluation team to decipher the subject matter knowledge embedded in panelists’ responses. The Delphi results from IEG’s global panel of experts on RE were analyzed in three steps:

- Future opportunities and challenges for scaling up RE for achieving the clean energy transition.

- Reform actions or solutions related to these opportunities and challenges.

- The Bank Group’s readiness to support clients in implementing actions or solutions.

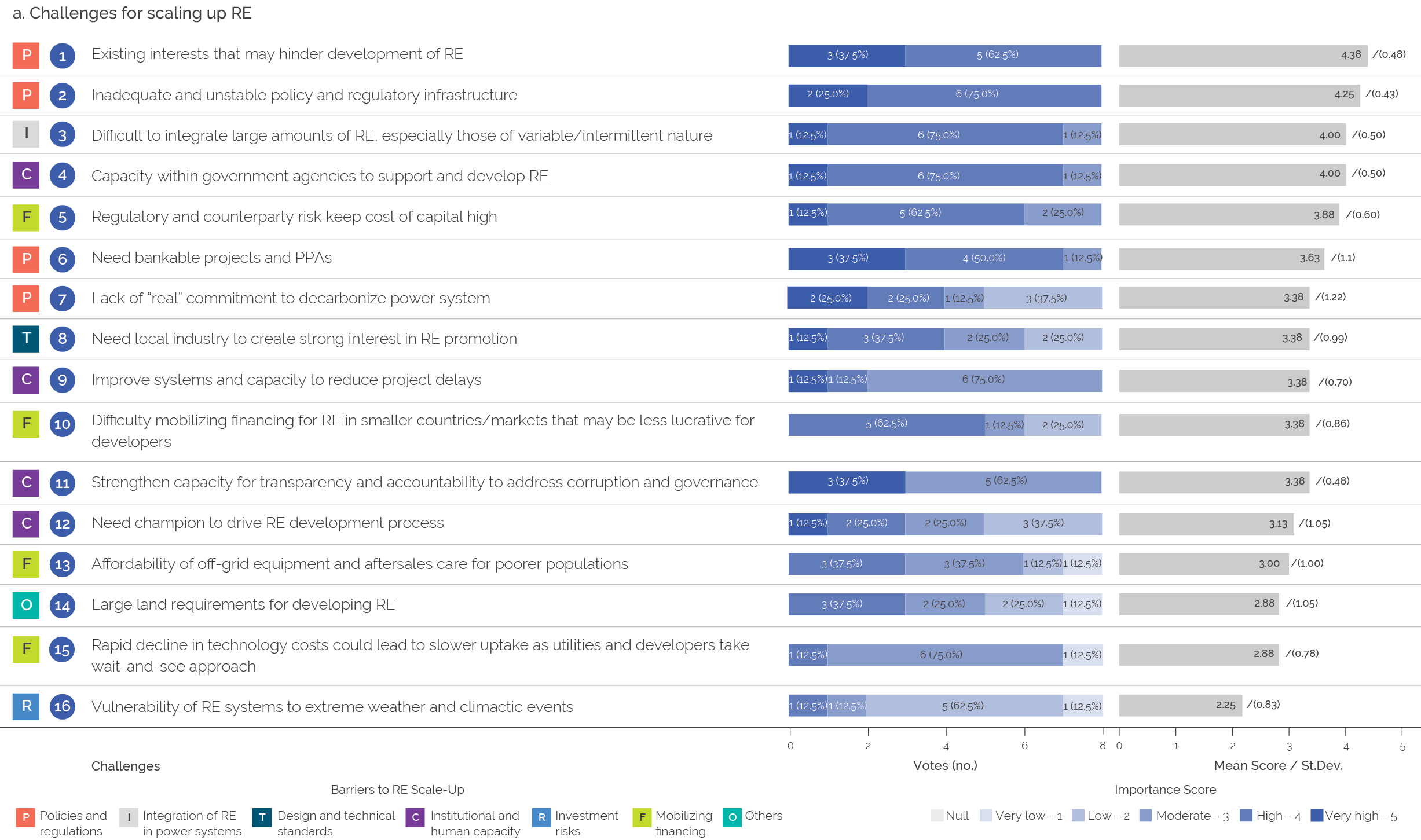

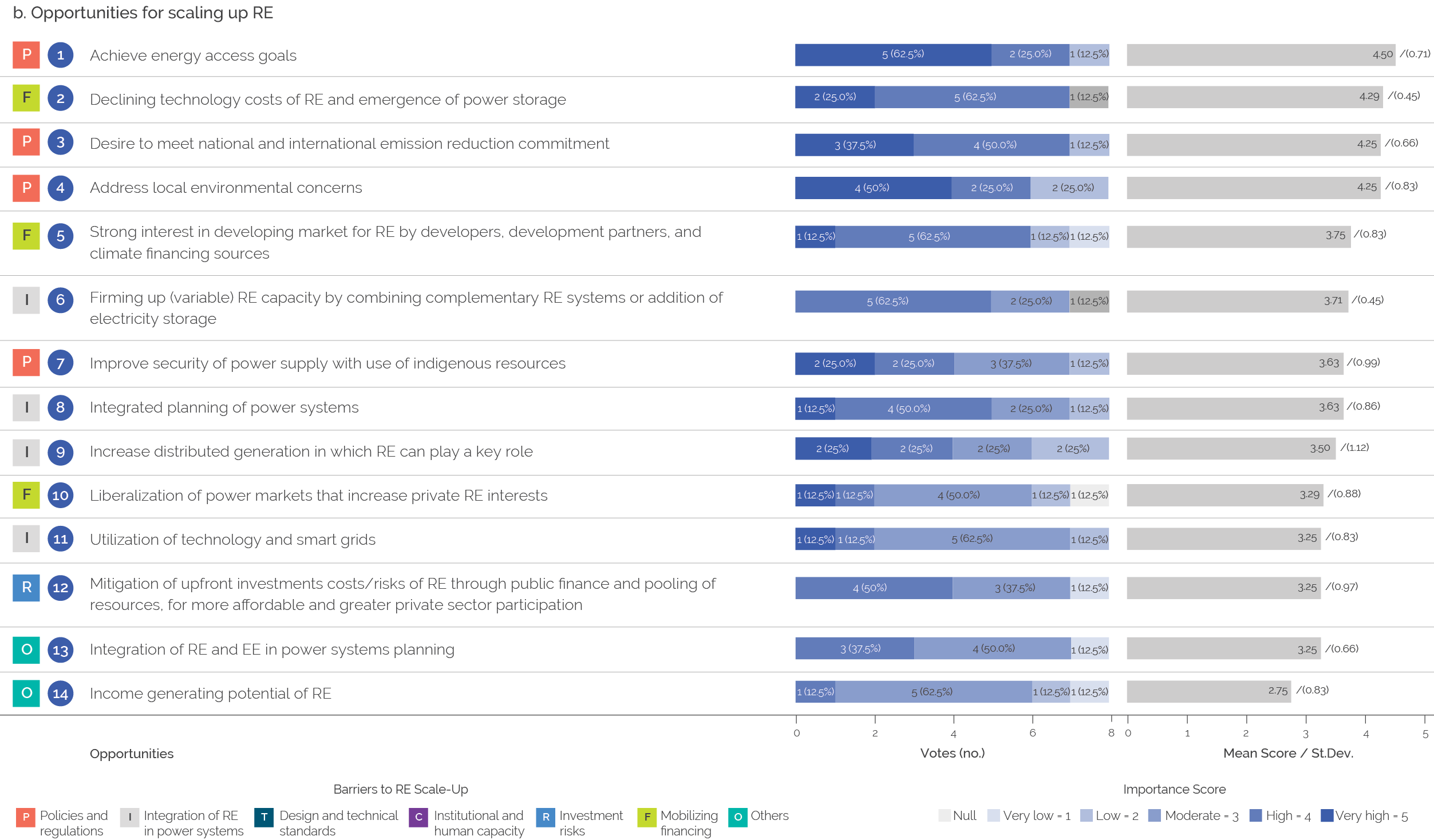

Analyzing Opportunities and Challenges

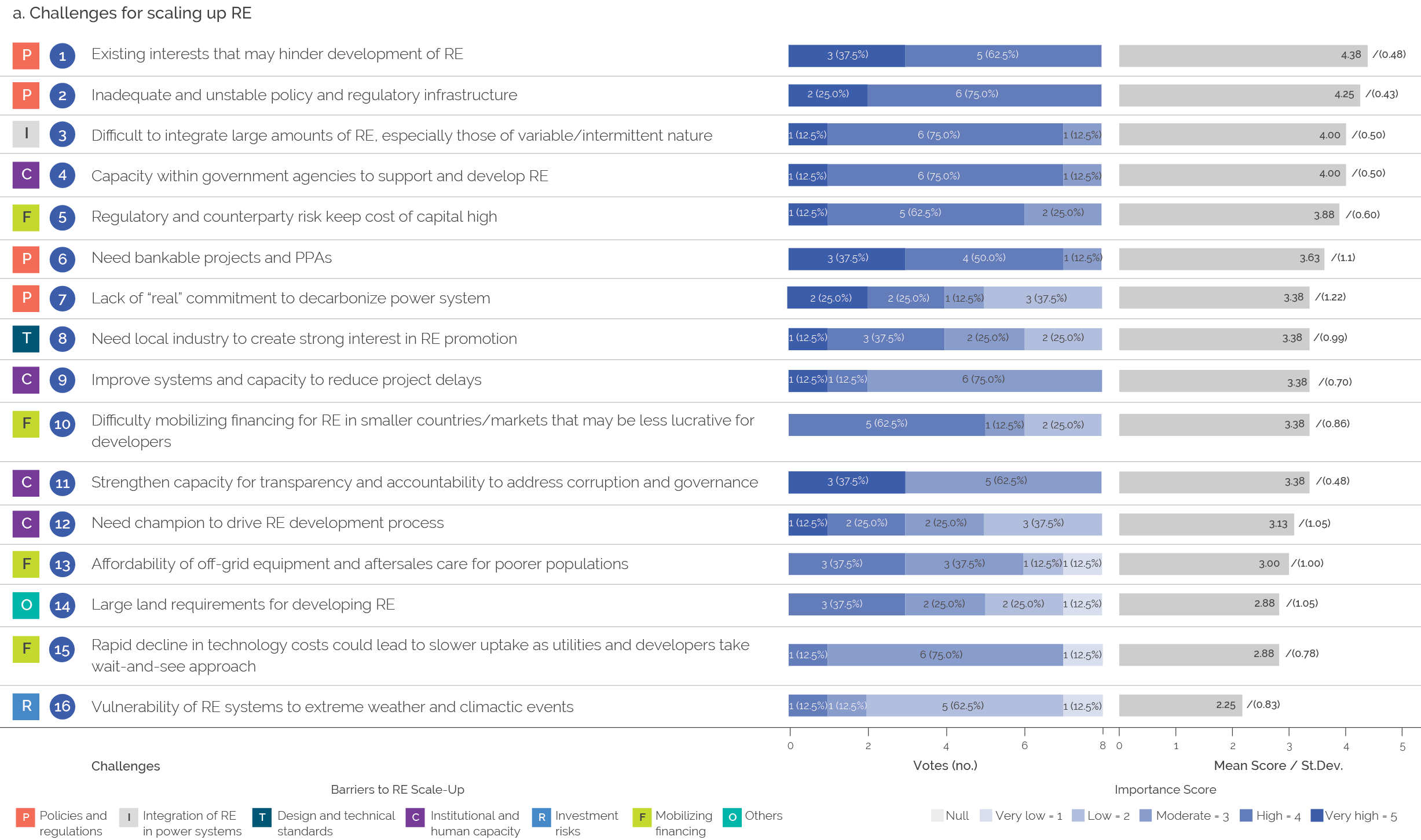

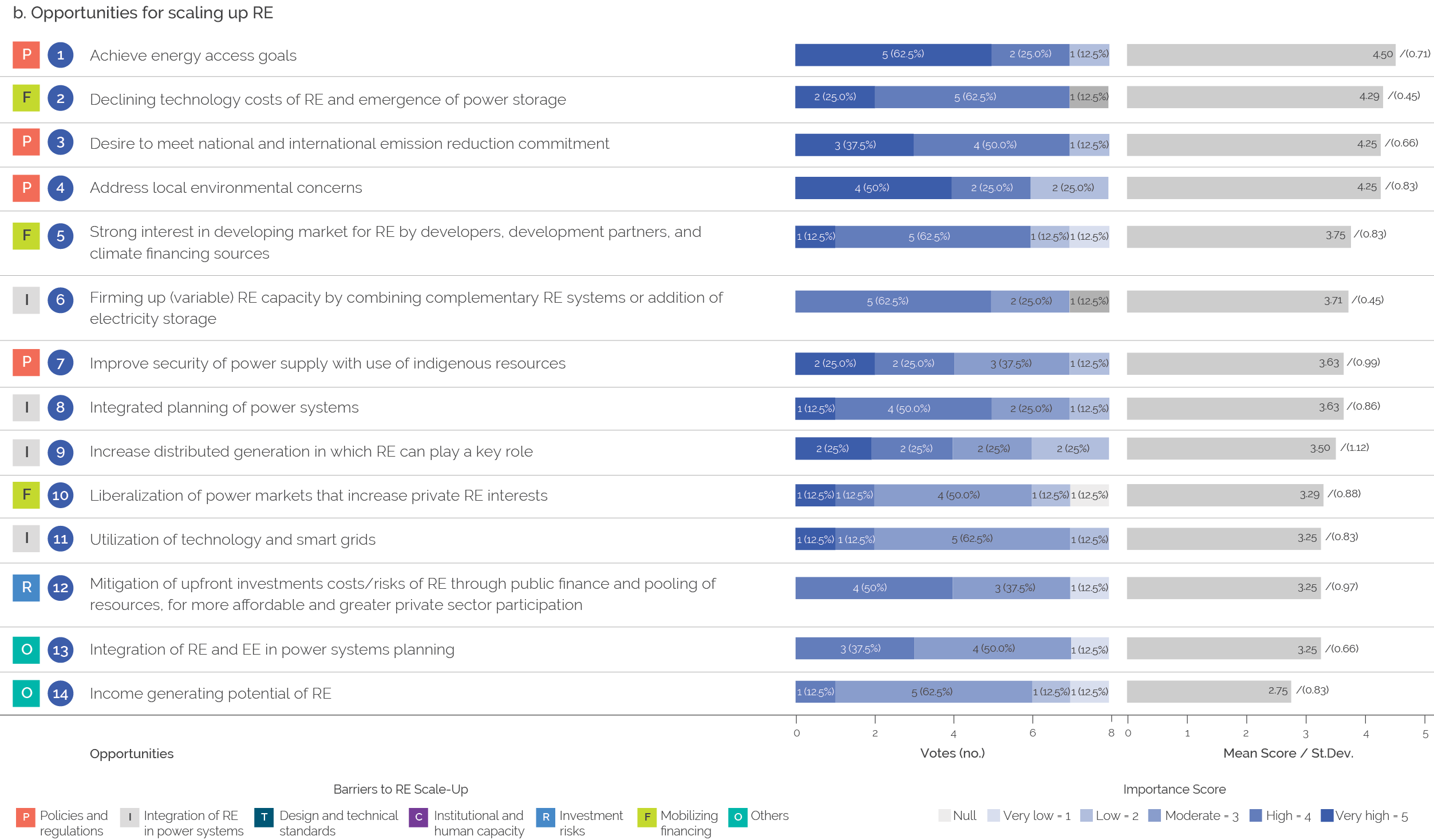

The first step was to analyze the major conclusions that can be drawn from the 14 opportunities and 16 challenges that were identified by the panel. The responses were analyzed based on a combination of scores on importance (indicated by average of the five gradations of Likert scale scores from very low to very high), and dispersion of scores across the panel (indicated by standard deviation from the average Likert score) as a proxy for the degree of consensus among the experts. The two parts of figure 5.2 summarize the results from the panelists’ feedback for the challenges that are expected to confront the future expansion of RE and for emerging opportunities that developing countries can seize to scale up the sector. Often, opportunities identified by the panel highlighted the need to address corresponding challenges. In some instances, opportunities reflected emerging options for addressing some of the future challenges RE will face. In other instances, lower-priority items reinforced related higher-order challenges or opportunities. The following section accounts for these links in analyzing the feedback from the panelists. It presents conclusions that are an amalgamation of challenges and opportunities, broadly paraphrasing the views expressed by IEG’s global panel of experts on RE.

The desire to meet national and international commitments to reduce greenhouse gases will open up greater opportunities for scaling up RE, although existing interests for maintaining the status quo can greatly hinder progress. IEG’s global panel of experts on RE noted the greater global awareness of climate change and the associated nationally determined commitments made by countries to reduce CO2 after the Paris Agreement as a high-ranking (third of 14) opportunity for scaling up RE. Greater consideration of carbon prices can also create a level playing field for RE in relation to other technologies. However, the top challenge that could stymie the expansion of RE, according to the panel, is resistance from vested interests. The opposition could be from coal and other fossil fuel–based interests that stand to be displaced by greater market penetration by RE. These industries could end up with stranded (existing) assets and suffer job losses as a result. Some power utilities may also resist a transition to increased generation from RE. This could occur when the scale-up occurs through independent power producers, which may be perceived as a loss of dispatch control within their operations, or if utilities are compelled to make additional costly investments in dispatchable capacity for integrating RE, especially variable renewable energy (VRE).

Figure 5.2. Prioritization of Challenges to and Opportunities for Scaling Up RE

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: EE = energy efficiency; RE = renewable energy; PPA = power purchase agreement; VRE = variable renewable energy.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: EE = energy efficiency; RE = renewable energy; PPA = power purchase agreement; VRE = variable renewable energy.

Several specific barriers, consistent with the ToC for the RE evaluation, were predicted to prominently challenge the scaling up of RE as the sector quickly expands and markets continue to evolve. Therefore, to achieve the targets in the clean energy transition, countries and RE stakeholders will need to adequately address these barriers to mobilize investments in the sector. The panel stressed the following:

- Inadequate and unstable policy and regulatory framework. All panelists viewed the importance of this barrier as high or very high. They perceived a stable RE policy framework, in which the direction of the sector is predictable, as a requirement for scaling up RE, especially for gaining the confidence of private investors. The enforcement of policies, including through an independent regulator, was seen as vital for attracting high-caliber developers. The panel also recognized that fair pricing policies are needed to ensure the financial viability of utilities and to attract investors, including the availability of bankable RE projects and adequate offtake agreements. Also, lack of transparency in procurement and other related processes can result in governance issues that can stymie competition and dissuade qualified developers from participating in the RE sector.

Inadequate policy and regulatory framework

Shortcomings in the policy and regulatory environment established by governments can hinder public and private investments in RE, especially when they do not provide adequate opportunities or incentives for investors.

Barrier as defined in the RE evaluation

Difficulties integrating large amounts of RE, especially those of a variable or intermittent nature, without enhancing the flexibility of power systems. Nearly 90 percent of the panelists scored this barrier as having high or very high importance, ranking it as one of the top three challenges for scaling up RE. This reflects the decreasing technology costs for solar PV and wind power, leading to a global expansion of VRE. This trend is expected to accelerate as reflected in the sizable share of the two technologies incorporated in the clean energy transition. Integrating increasing shares of VRE requires greater flexibility in power systems to accommodate intermittent availability of these RE resources. Although integrated planning of power systems garnered less significance on its own as a barrier, the panel acknowledged that a holistic approach is an important part of enhancing system flexibility to avoid bottlenecks and speed up RE deployment. Improved planning specially to integrate VRE should include building out transmission networks to supply demand centers, and where feasible, interconnection of power grids (within country or with other countries) to create future regional networks. There was extensive input by the panel on energy storage and its prospects (including from responses to additional question on the subject), which, together with other tools for integration, will have a significant impact on achieving the clean energy transition. The panel emphasized that the cost of battery storage at utility scale is already declining but acknowledged that this is presently uneconomical for most systems as a solution for integrating VRE (and that these costs should be included as part of the investment costs of VRE technologies). However, there was considerable consensus that economical battery storage is a clear and emerging trend, with some indicating a near- to medium-term time horizon when it will be cost-effective at large scale. There was also a call for developing hydropower (including pumped storage), which is presently an economical solution for sustainably enhancing system flexibility. Another emerging trend is the expansion of distributed generation (DG) from RE (including ambitious targets established in countries such as China and India), which can help integrated RE by injecting electricity directly into the distribution system and bypassing potential short-term transmission bottlenecks.1 The panel was divided and unable to reach consensus on the subject, since half viewed DG from RE as important or highly important and the other half thought its significance was moderate or low.

Inability to integrate RE into power systems

Inadequate planning, transmission bottlenecks and insufficient capacity, limited scope for power trading and pooling, inability to store electricity—can all result in inflexibility of power systems to smoothly and efficiently integrate RE, especially as the share of VRE such as wind power and solar PV increases.

Barrier as defined in the RE evaluation

- Inadequate capacity within governments to implement their RE development plans, including facilitating private investment mobilization. Most panelists viewed this as a shortcoming of high significance, as it leads to implementation delays and higher costs of projects and programs. Limited experience and capacity within energy ministries and other related institutions on RE-related issues was seen to disadvantage governments when negotiating with investors. The capacity constraints that extend the time necessary to design, build, and commission investments lead to higher costs that can compromise their economic viability. This is especially the case when mobilizing investments in advanced RE and related technologies, according to the panel.

Weak institutional and human capacity

In many developing countries, various institutions involved in the development of RE do not have sufficient capabilities to undertake new investments or operate ongoing projects.

Barrier as defined in the RE evaluation

- Regulatory and counterparty risks can increase the cost of developing RE. This is especially the case given the capital intensity (for example, high up-front costs) for many RE technologies. As noted by the panel, this can limit or make expensive available financing for RE projects; driving up costs of investments makes RE-based generation options less competitive. The panel indicated that countries with similar natural resource potentials have widely different levels of RE investments and costs as a result. Some panelists saw an opportunity to mitigate some of these risks through public financing (initial investments and then divesting) and pooling resources. Such initiatives were viewed as being especially useful for mobilizing private investments in RE.

Existence of investment risks

Even with improved policies and enhanced institutional capabilities, there may be residual risks that projects face, either on a transitional basis while reforms are being implemented or permanent risks that are outside the control of developers, and which may discourage investments (such as commercial or off-taker risks, political risks, RE resource risks).

As defined in the RE evaluation

- Several other challenges to overcome were identified, which may have significance in specific environments for developing RE. The need to develop local industries in RE was rated by some panelists as being high in importance. Although such efforts to develop local capacity propelled a country such as China to become a global leader in RE development, it may be a lower priority for smaller countries with less resource potential, smaller markets, and more limited human capacity. The challenge of mobilizing financing in smaller countries or markets was also raised, since these may be less lucrative for developers to invest in (ranked 10th out of 16 challenges). Further down the list of priorities was the potentially large land requirement for developing utility-scale RE, which can be a unique but important challenge in geographically smaller countries or densely populated areas. There was also acknowledgment that mobilizing supply-side solutions to climate change through the development of RE is only a partial pathway to achieving the greater objective of mitigating climate change, and that efforts should be combined with energy efficiency initiatives for better demand-side management of electricity use.

Although the overarching premise for the clean energy transition is to supply electricity sustainably through RE and avoid global environmental pollution, it is also an opportunity to achieve several other local development priorities prevalent in select circumstances. IEG’s global panel of experts on RE highlighted several energy and environmental benefits that are also part of the RE evaluation ToC that may accrue from scaling up RE (box 3.1):

- Achieve energy access goals. The highest-rated opportunity from expanding RE among the 14 identified was the ability to achieve energy access goals, echoing one of the key objectives of SDG 7. It was scored by over 60 percent of the panel as having very high importance and seen as an opportunity to connect the nearly 1 billion people presently living without electricity. The decreasing technology costs of RE were seen as a way of more affordably expanding electrification to people living in poverty. Off-grid RE was also seen as a solution to overcoming various institutional and other constraints facing conventional grid expansion, through household-level connections and from the rollout of self-standing minigrids as a regional electrification pathway in areas with little or no access to electricity in developing countries.

- Address local environmental concerns. The panel noted that fossil-based generation “presently contributes to three million premature deaths, which may increase to between six and nine million fatalities by 2060,” if current trajectories continue. As a result, addressing local pollution was ranked fourth among the 14 opportunities identified for expanding RE, with half the panelists placing very high importance on the matter. Recent challenges facing large cities such as Beijing, China, and New Delhi, India, underscore the importance of addressing local pollution from power generation and point to RE as a key solution. Ultimately, the direct benefits of avoiding local pollution may be as much a factor for countries developing their RE resources as global climate considerations.

- Improve security of power supply with the use of indigenous resources. The use of indigenous RE resources can enhance energy security by limiting exposure to the volatility of international markets, since it reduces reliance on fossil-based alternatives that are subject to price fluctuations typical of tradeable commodities. However, this ranked in the middle of the list of opportunities identified by the panel (seventh of 14). Although 25 percent of the panelists found energy security from developing RE to be of very high importance, half of the group viewed the opportunity as moderate or low in significance.

Analyzing Actions or Solutions

The second step was to analyze the actions or solutions that IEG’s global panel of experts on RE mapped to different challenges and opportunities to scale up RE. Therefore, the primary focus of this section is the actions or solutions that correspond to the priority challenges and opportunities highlighted in the previous section. The conclusions and sector narrative are drawn from the priority actions or solutions identified by the panelists based on the corresponding numeric Likert scale scores: (i) solid rating of important or very important (a Likert scale average score of 4.0 or higher marked as green in tables 5.1 to 5.5); (ii) a rating of important at the lower end (a Likert scale average between 3.5 and 3.99 marked as yellow in tables 5.1 to 5.5); and (iii) a rating of moderate importance or lower (a Likert scale average below 3.5 marked as blue in tables 5.1 to 5.5). As in the previous section, the standard deviations from average scores were used to gauge the consensus within the panel for the selected actions or solutions. Panel responses were interpreted into a narrative based on subject matter expertise and sector context.

Phasing out existing fossil-based power plants and avoiding construction of new ones will need to consider and address the concerns of stakeholders affected by the transition, including power utilities and investors with stranded assets. IEG’s global panel of experts in RE affirmed the need to strategically displace fossil fuels over time. The highest-rated actions included phasing out the most polluting power plants, especially in hotspots where they are a major contributor to poor local air quality. To a lesser degree, the panel also called for the cessation of constructing new fossil-based power plants and the removal of fossil fuel subsidies that exist in some 40 countries worldwide.2 The resulting unmet demand can then be supplied from RE sources. However, the panel clearly recognized that such actions will generate resistance from fossil-based interests, which stand to lose business and suffer potential losses as a result of stranded assets. As noted previously, these existing interests were identified by the panel as the most important challenge or barrier that could hinder the expansion of RE. Therefore, a successful transition would need to address these concerns, including alternative opportunities for investments and employment in RE and other areas. Furthermore, the panel placed a high level of importance and reached considerable consensus on the need for a long-term view and targets agreed with power utilities, since their operations can also be affected by greater use of VRE resources, increases in distributed generation, and, in some cases, the growing supply from independent power producers. Ultimately, it was proposed that clear policies and legislation will be required to set targets for expanding RE and displacing fossil-based generation. There was a recognition of opportunities to learn from the experiences in other countries in resolving these issues and transitioning smoothly. Table 5.1 provides a list of key proposed actions or solutions as prioritized by the panel for addressing existing interests that may constrain the expansion of RE.

Table 5.1. Actions or Solutions to Address Existing Interests That May Hinder Development of Renewable Energy

|

Actions or Solutions Proposed by Delphi Panel |

Priority Ranking mean (std. dev.) |

|

|

Existing interests may hinder development of RE |

Phase out fossil fuel power plants over time, starting with the most polluting ones |

4.38 (0.70) |

|

Closure of strategically located coal-based power stationsa |

4.25 (0.66) |

|

|

Legislate clear long-term RE targets and agree with utility how to achieve these targets |

4.13 (0.33) |

|

|

Create alternative employment for areas affected by removing fossil electricity production |

4.00 (0.50) |

|

|

Identify hotspots where power generation is a major contributor to local air quality and provide strong incentives for switch to REa |

4.00 (0.71) |

|

|

Legislate market liberalization to allow IPPs |

4.00 (1.00) |

|

|

Stop building fossil fuel–based power plants |

3.88 (1.17) |

|

|

Bring off-grid options into long-term electrification plan |

3.75 (1.09) |

|

|

Learn from successes of other countries |

3.63 (0.48) |

|

|

Remove subsidies on kerosene |

3.63 (1.22) |

|

|

Increase awareness on job creation potential of RE |

3.38 (0.70) |

|

|

Experiment with off-grid electrification concessions |

3.25 (1.09) |

|

|

Provide incentives to convert conventional power plants into RE, storage, or both |

3.25 (1.20) |

|

|

Remove VAT and import duty on solar |

3.00 (1.12) |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: IPP = independent power producer; RE = renewable energy; VAT = value-added tax. a. Reflects a related action or solution identified for seizing an opportunity.

The significance of rectifying an inadequate policy and regulatory framework to improve the investment climate for mobilizing investments in RE was underscored by the strong consensus within the panel that all corresponding actions or solutions identified by them are important. This includes modernizing the policy framework for promoting RE, with new or revised legislation and policies regarding national strategies on energy that align with the goals in SDG 7. The panel also called for avoiding or removing statutory or regulatory policies that can be barriers to the deployment of RE, and for fair and predictable implementation of policy through greater independence of regulators. The likely need to streamline permitting and development processes was recognized, especially for accelerating RE development through the private sector. Reforms were proposed for tender processes, including consideration of competitive bulk procurement for RE capacity, and for factoring life cycle costs and the potential for avoiding greenhouse gases in investment decision-making. Such approaches need to be supported by strong anticorruption laws and robust and consistent enforcement so that market confidence is enhanced to attract investments. The selected developers should also be subject to adequate environmental review and land acquisition. Depending on the extent of these reforms and the existing market structure, electricity market restructuring may be required. Table 5.2 provides a list of proposed key actions or solutions as prioritized by the panel for overcoming an inadequate and unstable policy and regulatory framework that affects the investment climate for RE.

Table 5.2. Actions or Solutions to Address Inadequate Policies and Regulations

|

Actions or Solutions Proposed by Delphi Panel |

Priority Ranking mean (std. dev.) |

|

|

Inadequate and unstable policy and regulatory infrastructure |

Facilitate easier finance for RE by reducing policy-based risks to such investmentsb |

4.50 (0.50) |

|

Create enabling environment for investments in RE—modernized legislation, energy policy, independent regulatorb |

4.38 (0.48) |

|

|

Develop stable policy frameworks that support RE development |

4.38 (0.70) |

|

|

Amend procurement or tendering practices to allow for consideration of life cycle costs when making decisionsb |

4.13 (0.33) |

|

|

Do not erect statutory or regulatory barriers to the deployment of hybrid technologiesb |

4.13 (0.60) |

|

|

Establish independent electricity regulator |

4.13 (0.78) |

|

|

Undertake electricity sector restructuring |

4.13 (0.78) |

|

|

Encourage rule of law through strong anticorruption laws and robust, consistent enforcementa |

4.13 (0.78) |

|

|

Inclusion of GHG price (as a cost) in cost-benefit analysis for new generation capacityb |

4.13 (0.78) |

|

|

Develop national RE strategies and long-term plans |

4.00 (0.71) |

|

|

Align national energy policy to achieve targets in SDG 7 to receive official development assistanceb |

4.00 (0.71) |

|

|

Repeat bulk procurement of RE electricity on a competitive basis to accelerate price reductions with increasing volumesb |

4.00 (0.71) |

|

|

Streamline permitting and development processes, including adequate environment review and land acquisitiona |

4.00 (0.87) |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: GHG = greenhouse gas; RE = renewable energy; SDG = Sustainable Development Goal.a. Reflects an action or solution related to addressing a different challenge.b. Reflects an action or solution related to seizing an opportunity.

Integrated planning and strengthening grid infrastructure for transporting RE to demand centers was seen as vital for expanding RE, followed by measures for balancing power and especially for assimilating VRE. The panel placed the highest importance on prioritizing grid infrastructure investments to improve the transmission and distribution networks to accommodate RE. There was a similar call to modernize grid operations and governance and strengthen the capacity of grid operators. Given the anticipated expansion of VRE, the panel placed high importance on solutions to support the integration of solar PV and wind power. Key proposed solutions included the promotion of pumped-storage hydropower and battery storage. Integration of grids within regions or countries was also viewed as an important solution for scaling up RE, since it can present more options for balancing power. Although the adoption of grid integration protocols, especially for RE DG, can ease some of the transmission bottlenecks and support load balancing in the short term, there was a divergence of views within the panel, as previously noted, on the significance of DG as a major long-term solution for scaling up RE. As the penetration of VRE increases in power systems, it may be necessary to reconfigure electricity markets to provide for price discovery of the balancing energy market. Although a key to integrating VRE is creating greater generation flexibility, the panel also recognized the complementary role that demand-side energy efficiency measures can play. Table 5.3 provides a list of proposed key actions or solutions as prioritized by the panel for better integrating RE into power systems.

Table 5.3. Actions or Solutions to Address Integration of Renewable Energy into Power Systems

|

Actions or Solutions Proposed by Delphi Panel |

Priority Ranking mean (std. dev.) |

|

|

Difficult to integrate large amounts of RE, especially those of variable/intermittent nature, without developing flexibility of power systems, which can be costly |

Improve transmission and distribution network |

4.38 (0.70) |

|

Prioritize grid infrastructure investmentsa |

4.38 (0.70) |

|

|

Integrate grid systems |

4.25 (0.66) |

|

|

Ensure adequate grid capacity for RE; modernize operations and governance of grida |

4.25 (0.66) |

|

|

Balance load to optimize local RE and grid electricity capacitya |

4.25 (0.66) |

|

|

Develop and adopt grid integration protocolsa |

4.13 (0.60) |

|

|

Make it easier to integrate VRE sources into grid and support solutions that involve storagea |

4.13 (0.60) |

|

|

Strengthen capacity of grid operators |

4.00 (0.50) |

|

|

Promote pumped storage and battery storage |

3.75 (0.97) |

|

|

Undertake long-range transmission planning |

3.63 (0.86) |

|

|

Unlock flexibility in generation and the demand side by creating appropriate market incentives |

3.63 (0.70) |

|

|

Reconfigure electricity markets to provide for price discovery of balancing power |

3.50 (0.87) |

|

|

Monetize future loss reduction to pay for RE DG installations now |

3.50 (1.09) |

|

|

Develop smart grids |

3.38 (0.70) |

|

|

Develop risk guarantee mechanism to compensate fossil-based plants for capacity cost when use is too low to recover these costs because of preference for RE electricity |

3.13 (0.60) |

|

|

Progressively move to reflect full RE costs, especially as its share in energy generation rises |

3.13 (0.60) |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: DG = distributed generation; RE = renewable energy; VRE = variable renewable energy.a. Reflects an action or solution related to seizing an opportunity.

Strengthening the capacity within government agencies would improve the implementation of public projects and also make them better partners in facilitating private investments in RE. IEG’s expert panel on RE placed very high importance on the capacity to plan, implement, and monitor and evaluate RE investments—spanning the spectrum of a typical project cycle. Given the fast-evolving RE markets, similar significance was placed on training businesspeople, managers, and engineers, so they are familiar with the latest developments. Although such voids can be filled to an extent by mobilizing domestic and foreign private actors, the capacity within governments to negotiate such agreements is often lacking. The panel proposed seeking development partner assistance as a solution. They stressed that many countries have national plans but often lack the human capacity to implement them. The actions or solutions proposed by the panel for strengthening capacity were, however, limited and general, as shown in table 5.4—a deviation from the extensive suggestions made for other high-ranking challenges.

Table 5.4. Actions or Solutions to Develop Capacity for Supporting Renewable Energy

|

Actions or Solutions Proposed by Delphi Panel |

Priority Ranking mean (std. dev.) |

|

|

Capacity within government agencies to support and develop RE |

Capacity within government agencies to support and develop RE |

4.50 (0.71) |

|

Training on RE for businesspeople, managers, and engineers |

4.00 (0.87) |

|

|

Seek support from development partners to assist with negotiations to be undertaken |

3.75 (0.97) |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: RE = renewable energy.

Approaches to reducing counterparty risks can facilitate financing for RE by making projects more bankable for investors. There was significant consensus regarding the high importance placed by the panel on actions to de-risk or minimize counterparty risks faced by RE investors, including using grants or concessional finance, and consideration of life cycle costs in decision-making. The highest score given by the panel for risk mitigation actions was for developing a clear and robust investment framework, although there was considerable divergence of opinions within the panel regarding the solution. A specific proposal was that smaller countries could pool similar projects within a region to generate greater investment interest through economies of scale. A less significant solution was to have a risk guarantee mechanism to compensate fossil fuel plants for underuse of capacity resulting from preference for RE, so that they will not present a roadblock for scaling up RE as an alternative. Table 5.5 provides a list of proposed key actions or solutions as prioritized by the panel for better mitigating investment risks.

Table 5.5. Actions or Solutions to Mitigate Regulatory and Counterparty Risks

|

Actions or Solutions Proposed by Delphi Panel |

Priority Ranking mean (std. dev.) |

|

|

Regulatory and counterparty risks keep cost of capital high |

Create a clear and robust investment framework |

4.25 (0.83) |

|

Amend procurement or tendering practices to allow for consideration of life cycle costs when making decisionsb |

4.13 (0.33) |

|

|

Minimize counterparty risk |

4.00 (0.50) |

|

|

Explore opportunities for de-risking investments through the use of grant or concessional financinga |

4.00 (0.50) |

|

|

Organize small countries to pool similar projects in same regiona |

3.75 (0.97) |

|

|

Develop risk guarantee mechanism to compensate fossil-based plants for capacity cost when use is too low to recover costs because of preference for RE electricitya |

3.13 (0.60) |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: RE = renewable energy.a. Reflects an action or solution related to addressing a different challenge. b. Reflects an action or solution related to seizing an opportunity.

Analyzing the Bank Group: Readiness to Support Clients

The third step was to analyze the Bank Group’s role in terms of its readiness to support the clean energy transition. IEG’s global panel of experts on RE shared their perception of the Bank Group’s position (to influence the outcome) and its capacity (expertise and experience) to support clients, for each action or solution for addressing challenges and seizing opportunities. Therefore, the primary focus of this section is the institution’s readiness to support clients in implementing various reforms (actions or solutions) identified by the panel. It is important to interpret this information with greater caution, and ensure it is ultimately corroborated with other methodological sources. Although the panel has extensive expertise in RE development globally and each member is familiar with the work of the Bank Group, their respective understanding of the institution and its functions and their own experience with it may vary considerably. Therefore, the views of the panel on the institution’s role may be less generalizable.

The Bank Group’s position and capacity to support clients to implement specific actions or solutions is scored on a different scale. The panel was presented with a four-point Likert scale (instead of a five-point scale). The scale for the Bank Group’s position to influence outcomes was 4—extremely well, 3—very well, 2—moderately well, and 1—poorly; the scale for institution’s capacity to support clients undertake actions or solutions was 4—very high, 3—high, 2—moderate, and 1—low. In both cases, each panelist had the option to not opine (by responding “Do not know” or “No opinion”), although the response rate with a perspective was 84 percent (89 percent for position and 79 percent for capacity). As for previous sections, the results were analyzed based on priorities identified through panel scores (mean, standard deviation).

Overall, the Bank Group was moderately well to very well positioned and had moderate to high capacity to help clients navigate the clean energy transition. The average score for the Bank Group’s position to influence the 16 challenges was 2.61 and the 14 opportunities was 2.56, which is at the lower end of “very well”, barely surpassing “moderately well.” The institution’s capacity to support clients to undertake actions or solutions was only slightly better, for challenges at 2.66 and for opportunities at 2.73, at the threshold between “moderate” and “high.” The panel did not view the Bank Group to be extremely well positioned or possess very high capacity to influence the clean energy transition. Mitigating regulatory and counterparty risks was the only priority challenge where the Bank Group was perceived to be clearly very well placed with high capacity to support clients. The panel viewed the institution as very well positioned (mean 3.13, std. dev. 0.72) and having a high level of capacity (mean 3.00, std. dev. 0.88) to help clients develop a clear and robust investment framework and help minimize regulatory and counterparty risks, which likely reflects the multiple instruments available within the Bank Group for risk mitigation (guarantees, political risk insurance, concessional financing, and ability to mobilize grants). The score was also likely based on the institution’s role helping improve the regulatory and policy frameworks in client countries (another high-ranking challenge, noted previously). Risk mitigation also garnered one of the highest levels of consensus for a challenge within the panel.

The Bank Group’s readiness to support clients in addressing other priority challenges was perceived with greater ambiguity within the panel. Most were scored by the panel as being moderately well and very well placed and having moderate to high capacity to support clients. There was also a diversity of views that did not represent a definitive consensus, which may reflect the different experiences of panelists with the institution. The Bank Group’s readiness to help clients overcoming other priority barriers include the following:

- Inadequate policy and regulatory infrastructure. In the case of this barrier, the Bank Group’s capacity fell just below the threshold for a clearly high rating. Within the specific barrier, the institution was viewed as clearly having high capacity to help clients develop RE strategies and long-term plans and to support power sector restructuring where there are clients committed to such reforms, although its ability to help establish and support independent regulators was rated modest. The Bank Group was seen to have between moderate and high capacity for helping develop a stable policy framework for RE.

- Integration of RE to power systems. Although the overall rating for capacity to help clients overcome this barrier was mostly modest, integration of grid systems and promoting pumped-storage hydropower and battery storage were specific actions where the Bank Group was viewed to have high capacity (and was very well positioned). Integrated systems and long-range transmission planning capacity was also perceived to be high, although the institution was seen to be less influential with clients in this regard. The Bank Group had more moderate capacity for many other related actions or solutions, including unlocking flexibility in generation and reconfiguring power markets for price discovery for balancing power; developing smart grids; strengthening capacity of grid operators; increasing RE DG; and even to some extent improving the transmission and distribution networks.

- Lack of capacity within governments to develop RE. The Bank Group was very well placed with high capacity for training various officials in developing RE, which in turn would also help establish the public sector as a credible partner for the private sector to invest in RE. The institution was seen to be less capable in terms of supporting the public sector to negotiate various aspects of RE development with the private sector.

The Bank Group is very well positioned to mobilize financing for RE, especially in smaller countries or markets, according to the panel. Capital flows may be more limited in such markets, especially for financing emerging technologies or solutions. The institution was rated close to high in its ability to use grants and concessional financing to supplant such gaps. However, it is more modestly capable of organizing smaller countries to pool projects to attract financing.

The Bank Group is well placed to share successful experiences from other countries. The panel recognized the institution’s global footprint as positioning it very well to disseminate global knowledge based on its high level of experience in RE from other countries. It was seen as a way of contributing to overcoming existing interests that may hinder the expansion of RE.

The panel did not view the Bank Group as being particularly well positioned to help clients achieve electricity access and local environmental goals—two highly ranked opportunities that can be achieved by expanding RE. In both of these areas, the institution was moderately well positioned with moderate capacity. Within the actions or solutions for increasing access, the highest capacity rating was for helping clients align national policy with SDG 7. With regard to the local environment, the rating was highest for facilitating electricity-powered transport for reducing pollution. The panel gave a higher score for enhancing energy security using indigenous RE resources, although it was ranked as a lower-priority opportunity.

- However, scaling up of solar photovoltaics, in particular, will increase the share of variable renewable energy, which can, in turn, generate the need for more flexibility in power systems through additional dispatchable capacity of energy storage options.

- The list includes countries that provide direct subsidies for coal, oil, natural gas, and electricity. There are additional countries that may provide tax breaks and other incentives for fossil fuels, which can also undermine the competitiveness of renewable energy.