Creating Markets: Are PPPs the Answer?

World Bank Group experience suggests several fundamentals need to be in place for PPPs to contribute to infrastructure market creation.

World Bank Group experience suggests several fundamentals need to be in place for PPPs to contribute to infrastructure market creation.

By: Stefan ApfalterJosé Carbajo Martinez

If they are designed and implemented well, infrastructure PPPs ‘can deliver the goods’: mobilize private sector finance, help the public sector improve its procurement skills for the preparation, selection and design of infrastructure projects; transfer risks from the public to the private sector; achieve on-time and on-budget project execution; and ensure adequate service operations and maintenance.

Under the Maximizing Finance for Development (MFD) agenda, the World Bank Group (WBG) has outlined a new approach that prioritizes private financing and sustainable private sector solutions to help countries achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.

With its potential to attract private funding, design expertise and operational know-how, many view Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) as an example par excellence of private sector solutions that can help build infrastructure, deliver access, and provide quality services.

Much hope, therefore, rests on PPPs to help mobilize an estimated $1.8 trillion every year, the amount needed from the private sector to bridge the investment gap to achieve the SDGs. Most of these funds would flow into construction of basic infrastructure such as roads, railways, ports, power stations, water and sanitation. But is such hope realistic or overstated?

If they are designed and implemented well, infrastructure PPPs ‘can deliver the goods’: mobilize private sector finance, help the public sector improve its procurement skills for the preparation, selection and design of infrastructure projects; transfer risks from the public to the private sector; achieve on-time and on-budget project execution; and ensure adequate service operations and maintenance.

By contrast, poorly structured PPPs can quickly materialize high risks, and create many headaches for the public sector and private parties involved through a variety of unwelcome developments. Overly optimistic demand forecasts, for example, can quickly turn into insufficient revenue and lead to bankruptcy or public-sector bailout; poorly designed payment mechanisms can result in excessive tariff increases creating affordability problems; inefficient provision of government guarantees can have severe fiscal implications through the related contingent liabilities.

Hence, for PPPs to help deliver adequate services and create markets for infrastructure, a good understanding is required of the underlying incentives of the private parties involved and of the political economy factors that contribute to successful outcomes.

Recent IEG work, such as the 2014 evaluation on PPPs; the 2016 Synthesis Report on Health PPPs; and the 2017 Learning Note on Transformational Engagements contain a rich set of lessons from the PPP experience of the World Bank Group, which identify fundamentals required for PPPs to succeed and create markets for infrastructure:

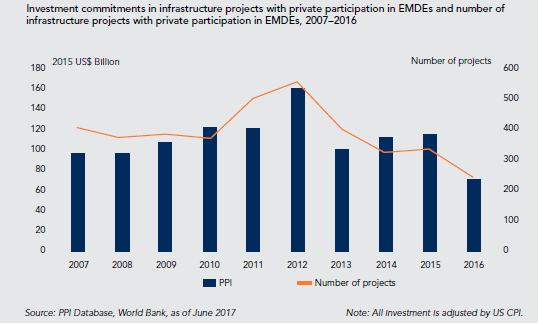

Perhaps the difficulty of putting in place all the above fundamentals, including the complexity associated with PPP arrangements, explains the recent decline in private sector participation in infrastructure. According to the 2016 World Bank Private Participation in Infrastructure (PPI) Database, the year 2016 experienced the lowest level of investment commitments compared with the previous 10 years. The volume of PPPs in 2016, for example, decreased by 41percent compared to the preceding five-year investment average of $121.4 billion.

A new report, Contribution of Institutional Investors to Private Investment in Infrastructure, paints an even gloomier picture: the current level of institutional investor activity in new infrastructure deals is only 0.7 percent of total private participation in infrastructure investment in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs).

This evidence points to the importance of the “Cascade Approach” in the Bank group’s MFD agenda, with its focus on remedying the obstacles that block private sector solutions. Helping client countries identify sound PPP opportunities and subsequently “de-risking” those through regulatory reform and building of national capacities appear more relevant than ever.

[NB: This is the third blog in the Creating Markets blog series. The motivation for the blog is to share lessons from relevant IEG evaluations early enough to help the Bank Group be successful in its systematic implementation of the Creating Markets concept.]

Comments

An excellent blog, and very…

An excellent blog, and very much aligned with our findings from an independent evaluation of 10 years of experience with PPPs in infrastructure in the Inter-American Development Bank (www.iadb.org/ove/ppp), which found that a thorough analysis of whether the environment is appropriate for a PPP and whether a PPP is the most appropriate option in a specific context is essential. It also found that strong collaboration between the public and private sector sides of the IDB Group is essential. It was good to see strong follow-up to the evaluation at the IDB, including a presentation together with IDB operations to discuss the findings and how to move forward (here is a link to the video): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6506v-3yKjs

Roland Michelitsch, Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE), Inter-American Development Bank (IDB)

Thank you Roland. It is…

Thank you Roland. It is interesting that many factors determining the success or failure of PPP arrangements are common across regions, including those our blog highlights. Another relevant finding from IEG's PPP-related work, which coincides with the IADB's infrastructure PPP evaluation your comment refers to, is the importance of a good organizational framework, the right skill mix, and staff incentives. Without those in place, IFIs tend to struggle to develop a PPP pipeline.

I am of the view that…

I am of the view that decline in PPP portfolio is not due to dearth of proper structuring and concession managing skills. We seem to have enough of that.

The issue is we are not able to take the PPP projects to its full life i.e. till the end of concession period. 25/ 30 years is too long a period for the assumptions/ basis of project structuring to be valid/sacrosanct. No doubt, the renegotiation (I would prefer to use the word restructuring) of concessions faces the issues of sanctity of contract, competitive bidding adopted while awarding the project and similar transparency issues but we do not have any option except to accept it.

So many in this field, feel the necessity but are not going ahead fearing from subsequent scrutiny by Regulating Agencies. The only way to handle it is to have transparent and detailed guidelines and implementation framework on the subject with least subjectivity.

To me this appears to be the most important step to arrest and reverse the declining trend of investment in PPPs.

Great blog and many good…

Great blog and many good ideas poured on it. However, time and again the picture about what "institutional" investors are after is often lost. This investors are investing someone else's money and their earnings are attached to successful transactions. Therefore, they are as adverse to risks as any other financial institution, or even more.

Greenfield projects, which account for the majority of the projects within those $1.8 trillion, are risky proposals that can barely capture a fraction of the money that those investors are able to mobilize, and as long as there are projects in the developed world, where the rule of law and the experience in this arrangements is already in place, projects in developing countries will be always a second or third priority, when not an exotic testimonial intervention, but rarely a tendency that will overcome the shortage of funding for infrastructure where is needed the most.

The ones that take the initiative in developing those infrastructure remain pretty much within the developers and contractors with limited resources for bidding and investing, but they cannot be locked in on many projects an in many places. Most PPP frameworks developed do not acknowledge the possibility to change the share ownership or securitizing those assets, making it possible for other investors to take stakes on the capital once the business have become less risky.

More than another guideline, or legal frameworks that are hard to enforce, these projects need to diminish the risks inherent to any new development and opening to the possibility for these institutional investors to invest on a fully functional system proven to produce results may be a step forward. Certainly the $ 1.8 trillion figure will still be needed to get the projects in place, but the moment that there is a secondary market feeding on projects developed, will certainly make easy to mobilize the primary market necessary to help those developers to carry on with the primary risks.

No. If it is about globe or…

No. If it is about globe or even bottom 40's. PPP's vary in accordance to the capacity, capabilities and most importantly will of state or governance structure and private individuals including multi national's demand and requirments. This is only possible when initiatives of PPP were designed, fixed with goals and time lines. Just wondering if sufficient research data findings available specifically for PPP sustainability is authenticated data? Don't we feel for more research with action's?

What I understand it's wise to experiment focusing individuals rather than group's, organisations and companies especially non profit, it's an amazing debate to discuss forget them at moments but essence of time is to realise the realities and justifications for quality, design and impact especially the region who are supposed to be beneficial.

Policy analysis very common terminology now a days but amezed to know anyalsis against what.

Fixing many things would be great before problem specific solutions. Law, regulations, functionary bodies of the state, what kind of governance structure opted, resources avaliable and required, demand of every human after globalisation through information technology.

Geographical, rule of law and sincere approaching efforts towards human development alliance with local demands will be hopefully core component of the idea with visible and measurable tools.

Add new comment