The World Bank Group in Madagascar

Chapter 5 | World Bank Group Support for Fostering Development in Rural Madagascar

Highlights

World Bank support to smallholders, although consistent with good practice, often overestimated the capacity of Madagascar’s farmers living in poverty, particularly in relation to supporting the adoption of improved technology.

The World Bank Group contributed to developing value chains, including poultry, beef, cocoa, and vanilla, as part of an integrated, regional approach, focusing on geographical areas with high growth potential. Success in integrating smallholders into agricultural supply chains, however, was more limited.

World Bank support contributed to short-term increases in agricultural production and resilience. However, this support contributed little to longer-term improvements in the livelihoods of rural smallholders (with the notable exception of benefits stemming from food security interventions).

The World Bank’s approach to supporting natural resource management and the environment shifted from a focus on biodiversity conservation to integrated approaches that combined agricultural support. It is still too early to gauge the effectiveness of this pivot.

World Bank support for human development led to tangible contributions and helped prepare the government to respond to the ongoing coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis.

The Bank Group’s support contributed modestly to developing Madagascar’s rural areas and improving the welfare of rural Malagasy. Support to rural areas consisted of efforts to enhance agricultural productivity (subsistence agriculture and support to value chains); natural resource management and the environment, including integrated land management; access to infrastructure; and access to basic services, including health, education, and social protection. However, results were limited given the lack of sustainability of many interventions (in part due to weather-induced shocks that reduced the impact of irrigation infrastructure) and challenges in the scale-up of others. This section details the Bank Group’s approach and efforts to support the development of rural areas.

Consistent Strategic Focus on Developing Rural Areas

The Bank Group focused on developing Madagascar’s rural areas and reducing rural poverty throughout the evaluation period. The CAS (FY07–11) noted that to achieve its poverty reduction objectives required a strong focus on developing rural areas, given the large concentration of poverty and low human capital there. The ISN (FY12–13) emphasized the need to increase the resilience of the most vulnerable (the majority of whom are in rural areas), which required a medium-term perspective on health, education, nutrition, and social protection. In the short term, however, attention was given to high-impact interventions in rural areas that created employment, smoothed consumption, and built or reconstructed productive assets (for example, infrastructure; World Bank 2011b).

This focus on rural development was supported by the World Bank’s diagnostic work on poverty in Madagascar. Figure 1.2 shows the geographic distribution of poverty in Madagascar. The SCD identified the need to give special attention to increasing agricultural productivity, enhancing management of natural resources, and creating mechanisms to protect rural Malagasy living in poverty from weather-related shocks. There was a clear recognition of the complex and cross-cutting constraints and bottlenecks to reducing rural poverty. This included recognition of the need for adequate and more efficient government spending on human capital (for example, health and education) and recognition of nutrition as a critical input to improving health, education, and productivity (World Bank 2015b). The CPF proposed measures to achieve its goals of increasing the resilience of the most vulnerable and promoting inclusive growth. To achieve these objectives, the Bank Group was to work in fewer areas but to employ multisectoral and integrated approaches to the interconnected challenges impeding the development of rural areas.

Agriculture, Agribusiness, and Food Security

The Bank Group supported agriculture, agribusiness, and food security over the evaluation period. The Bank Group supported the sustainable development of rural areas by seeking to (i) increase the agricultural productivity of smallholders, (ii) foster economic growth by developing global and domestic agricultural value chains, and (iii) provide safety nets for Malagasy living in vulnerable, food-insecure areas. Project support included the Rural Development Support Project; the Irrigation and Watershed Management Project; the Agriculture Rural Growth and Land Management Project; the Sustainable Landscape Management Project; World Bank and IFC agribusiness projects, such as the Integrated Growth Poles and Corridor projects; IFC’s investments in poultry, beef, and vanilla value chains; and the World Bank’s Emergency Food Security and Social Protection Project.

World Bank support to smallholders was consistent with evidence of what works but failed to adapt adequately to Malagasy smallholders. World Bank interventions focused on increasing agricultural production by (i) creating and rehabilitating irrigation and infrastructure; (ii) promoting new technologies and innovations to increase agricultural productivity and sustainability; (iii) supporting policy reforms—for example, land tenure, investment climate; (iv) supporting agricultural research and extension to build the capacity of farm organizations; (v) rehabilitating a small number of feeder roads to facilitate market access and rural connectivity; and (vi) developing and enhancing previously underexploited value chains. Box 5.1 describes some of the evidence from agricultural interventions on what worked, what did not work, and why.

Box 5.1. Agricultural Interventions: A Review of What Works, 2000–09

A systematic review of World Bank agriculture interventions spanning 2000–09 provided lessons on the impact of specific agricultural interventions. The global evidence from impact evaluations is consistent with the results of the World Bank Group’s engagement in Madagascar’s agriculture sector.

The following outlines the results by intervention in terms of percent positive (or negative) for various outcomes:

- Land tenancy and titling: 65 percent significant positive impacts—crop yield, value of production per hectare, agricultural profits, and household income across regions and types of reforms.

- Extension services: 50 percent significant impacts—beneficiary knowledge and farm yields. Extension services, designed to diffuse knowledge among farmers, such as training of trainers, did not produce the expected results. Trained farmers were not able to effectively demonstrate complex decision-making skills to other farmers.

- Irrigation schemes: 33 percent significant negative or nonsignificant impacts—agricultural or farm income. Negative or nonsignificant impacts were limited to microdams or water reservoirs, not canals or other irrigation infrastructure or technology. Negative or nonsignificant impacts were associated with, for example, declining labor productivity despite production increases.

- Marketing or farm groups (for example, value chain participation): 64 percent significant positive impacts—yields, crop prices (and profits), and value of production. Participating in value chains provided access to improved inputs, farming technology, and markets.

- Natural resource management: 50 percent significant impacts—farm yields or other agricultural indicators. Interventions that promoted technologies related to soil structure or composition—for example, stone bunds and systems for rice intensification (that is, guidelines for spacing and transplanting crops)—were most effective.

- Input technology interventions: 70 percent significant positive impacts—variety of farm outcomes (for example, improved seeds).

In addition, microfinance, rural roads, other infrastructure, community-driven development, and safety net interventions showed positive impacts on rural development outcomes related to farm performance. Those outcomes were primarily household income or consumption (poverty reduction).

Sources: World Bank 2011a, 2011b.

Note: Income = earnings from all activities; production = amount of farm production cultivated and farmed; profit = marginal gains or net benefits (sales minus costs) reported by farmers; yield = production or labor per total area of cultivated land.

World Bank support for the adoption of improved technology to increase agricultural productivity was not adequately targeted to smallholder production systems. The World Bank supported improving or intensifying rice cultivation, agroforestry, and conservation agriculture. However, many Malagasy smallholders were not able to adopt these new technologies (or adopted but quickly dropped them) because of human capital constraints (for example, education, labor, and poverty) or infrastructure constraints (which impedes farmers’ access to markets). Constraints included (i) the limited investment capacity of smallholders living in poverty, (ii) continued incentives to migrate to forest frontiers, (iii) risk aversion and the desire for immediate returns, (iv) social organization models that were not specific to the context of Malagasy smallholders, (v) low human capital, and (vi) lack of coordination at the sectoral and regional levels (including the need for substantial investments in transport and market organization). Smallholders require access to land and incentives to improve their land (for example, building terraces, fences, or irrigation schemes or using manure). Although aggregate agricultural productivity did increase somewhat, selective adoption of the new technologies by smallholder (or subsistence) farmers did not contribute significantly to this increase and therefore did not contribute to inclusive growth and rural poverty reduction objectives.

From about 2016, drawing on the findings of the SCD, the Bank Group’s agricultural engagement shifted from direct support to smallholders to support to agribusinesses and value chains. The World Bank’s support shifted to joint World Bank–IFC–MIGA efforts in an intersectoral approach to supporting the development and deepening of value chains. Smallholders were included in the design of these projects, given an expectation that these farmers could be integrated along the supply chain. The Integrated Growth Poles and Corridor projects supported value chains (for example, cocoa, cotton, seaweed, lychees, vanilla) as part of an integrated, regional approach, focusing on geographical areas with high growth potential. The World Bank’s Agriculture Rural Growth and Land Management Project focused on improving value chains (cinnamon, granadilla, lychee, turmeric, dairy, and small ruminants) through improving land security and providing safety nets and response mechanisms in the case of natural disasters. Support is ongoing to assist the government’s effort in amending law 2021-016, on untitled private property, which is expected to enable the distribution of more than 1 million land certificates to Malagasy households by the end of the project. IFC’s investments in agribusiness value chains relied on agricultural policies supported by the World Bank, which were included in the Integrated Growth Poles and Corridor projects (for example, land reform, investment climate reforms) and de-risking mechanisms (for example, linking investments with advisory services and using the de-risking mechanisms [blended financing] offered under the Private Sector Window of the Global Agriculture and Food Security Program; see box 5.2). IFC invested in medium- to large-scale clients in areas with export potential and backward links to small-scale farmers, developing agricultural value chains in poultry and beef processing and certified and traceable vanilla. Additionally, broader IFC investments in energy, transportation, and financial services had indirect impacts on rural development.

Successful value chain interventions provide lessons to replicate. The World Bank successfully supported the cocoa value chain. Interviews suggest that the Integrated Growth Poles and Corridor projects were an exception. Their success was due, in part, to collaboration with regional and local authorities and coordination of project activities, both of which were facilitated by regional implementation units, as noted earlier. Another important factor of success was the World Bank’s support to the National Cocoa Council. In Madagascar, cocoa production is managed through the Council, which involves all actors along the value chain. To replicate the approach of the Integrated Growth Poles and Corridor projects approach requires inclusivity along the value chain and institutions that are mandated to coordinate activities in project areas.

Box 5.2. International Finance Corporation and the Global Agriculture and Food Security Program: Efforts to Integrate Madagascar’s Smallholders into Value Chains

The Global Agriculture and Food Security Program (GAFSP) was added to the Private Sector Window during the 18th and 19th International Development Association Replenishments. GAFSP is a multilateral mechanism established to support private sector investments in sustainable agriculture. By de-risking investments, GAFSP sought to demonstrate the viability (profitability) of private sector investments in International Development Association countries. GAFSP investments sought to integrate smallholders into value chains, build smallholders’ capacity, and focus on investments that supported improving nutrition, empowering women, supporting gender equality, and adopting climate-smart agriculture.

Vanilla value chain. Investment by the International Finance Corporation helped integrate Madagascar’s smallholder vanilla farmers into a global agricultural value chain. The International Finance Corporation client increased its direct sourcing of vanilla from farmer cooperatives, which included smallholders, and an International Finance Corporation advisory services project helped farmers obtain proper certification and ensure traceability of their produce. The client’s business model supported sustainable vanilla sourcing; the company directly supported farming communities by improving access to health care and schooling infrastructure, cooperative management, and income diversification and loans, and its model was supported by corporate and social responsibility activities of one of the world’s largest vanilla suppliers.

Poultry value chain. GAFSP reinvested its participation in the project to directly benefit the community surrounding the International Finance Corporation investment. Approximately US$1.6 million was used to build schools, housing, health centers, and electricity infrastructure, among other community infrastructure, in the Anosy and Androy regions of southern Madagascar. (Androy is one of the poorest and most food-insecure regions of the country.) However, the business model of the poultry investment was not focused on integrating rural Malagasy farmers into the supply chain.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Successful integration of smallholders into agricultural supply chains was more the exception than the rule. To integrate into a cash crop value chain, farmers need to produce a marketable surplus, which would have required smallholders to move beyond subsistence agriculture. Combined with the lack of rural roads and electrification, incentives to increase investments, and other constraints, this was a significant hurdle to overcome.

The World Bank’s support contributed to short-term increases in agricultural production and resilience. Between FY07 and FY21, World Bank support rehabilitated and constructed irrigation systems, which contributed approximately 95,000 hectares of irrigated land (out of Madagascar’s 2.2 million hectares of irrigated land). The number of hectares was likely larger, as the cited number excludes the construction and rehabilitation of irrigation schemes supported by community-driven development and social protection project activities. For example, the Emergency Food Security and Social Protection Project’s cash-for-work program supported 2,321 activities, which included irrigation infrastructure, and contributed to increasing agricultural production, food security, and resilience.

Limited contributions of Bank Group agricultural support to longer-term improvements in the livelihoods of rural smallholders led to a shift to integrated approach to agriculture. World Bank–supported agriculture interventions targeted areas with the greatest production potential, typically large, irrigated plains, the highlands, or areas with potential for cash cropping, all of which are better off economically. However, interventions tended to benefit advantaged farmers capable of producing surplus crops, rather than vulnerable farmers (within rural areas). In certain value chains (such as rice), smallholders could not afford to invest in new technologies; technological adoption required higher investments, was riskier, and offered delayed benefits, which excluded smallholders. In response to this, the World Bank has increasingly designed projects implemented by multiple ministries and with interministerial coordination, such as the Sustainable Landscape Management and the Resilient Livelihoods in the South of Madagascar projects.

Natural Resource Management and the Environment

Over much of the review period, the World Bank–supported natural resources management program focused on protecting forest habitat by expanding the coverage and strengthening the management of Madagascar’s System of Protected Areas. For 25 years, the World Bank supported implementation of the government’s National Environmental Action Plan through a programmatic investment loan series of three environmental programs. This plan focused exclusively on protecting biodiversity by developing a system of protected areas that restrict human use (it did not work to address the drivers of biodiversity habitat destruction across the country). The EP3, effective from 2004 to 2015, was approved on an exceptional basis and was complemented by projects and technical assistance to facilitate access to carbon finance markets. EP3 aimed to simultaneously conserve the country’s critical biodiversity and improve the livelihoods of local communities dependent on natural resources. Specific activities that were supported included the preparation of forest management plans; the establishment of an endowment fund, expected to generate resources to cover the recurring costs of managing the protected areas; and forest maintenance, surveillance, and monitoring.

EP3 was successful in increasing the area of forests placed under protection status, but it did not reduce deforestation rates. This was in part because it did not adequately address underlying drivers of forest losses from declining agricultural productivity around forests. Production of staple crops is both a key livelihood activity for communities in the forest frontier and a driver of deforestation. Low soil fertility drives farmers to cut the forest, where soil fertility is higher.

One shortcoming, however, was that the World Bank’s planned complementary support for incentives for communities to change unsustainable production practices within and around protected areas did not materialize. The core activities of the EP3 project focused on the management of forests within the protected areas as the World Bank intentionally opted not to directly support local communities’ livelihoods. Indeed, the Project Appraisal Document explicitly notes that earlier, more ambitious, phases of the environmental program registered weak results when biodiversity and community livelihoods were addressed in the same project; it also recognized the need for complementary investments to reduce pressures on natural forests by intensifying agricultural production but made the assumption that this would be best addressed by the World Bank–financed Rural Development Support Project, which was operating in the same province. Although the implementation agencies of the two projects signed a memorandum of understanding for the rural development project to carry out community development activities for EP3, no Rural Development Support Project funds were earmarked to support communities around protected areas as a result of inadequate coordination in implementation (World Bank 2021d).

Through additional financing, EP3 added safeguard community development activities, but this did not improve farmer livelihoods or result in more sustainable use of forest resources. Safeguard activities included (i) safeguard compensation to individuals whose livelihoods were impacted by the loss of access to forest resources from the expansion of protected areas and (ii) community development activities to promote the transition to more sustainable agriculture production practices around protected areas. IEG found that safeguards compensation activities in EP3 were poorly designed, underfunded, and insufficient to compensate forest-dependent communities for the loss of income from long-term restriction to forest resources (World Bank 2021d). The community development activities provided (i) improved rice seeds and a year of technical support or (ii) small-scale livestock. However, these activities did not address the fundamental problem of low soil fertility, which encourages forest encroachment, and did not transition agricultural practices in the long term.1 IEG’s Project Performance Assessment Report of the project also found that many farmers abandoned the new techniques after the project closure.

Governance problems in the forestry sector also undermined the impact of EP3, as can be seen in the fact that deforestation rates did not decline. Lack of monitoring and lack of enforcement by the government were key drivers of deforestation. The World Bank’s support to help the government address illegal mining of rosewood (mentioned in chapter 4) was not effective. During the crisis period and EP3 implementation, illegal trafficking of rosewood increased as monitoring and enforcement capacity declined. Through the Sustainable Landscape Management Project, the World Bank is now supporting a government traceability system to improve forest governance, although IEG was unable to identify any preliminary results to date.

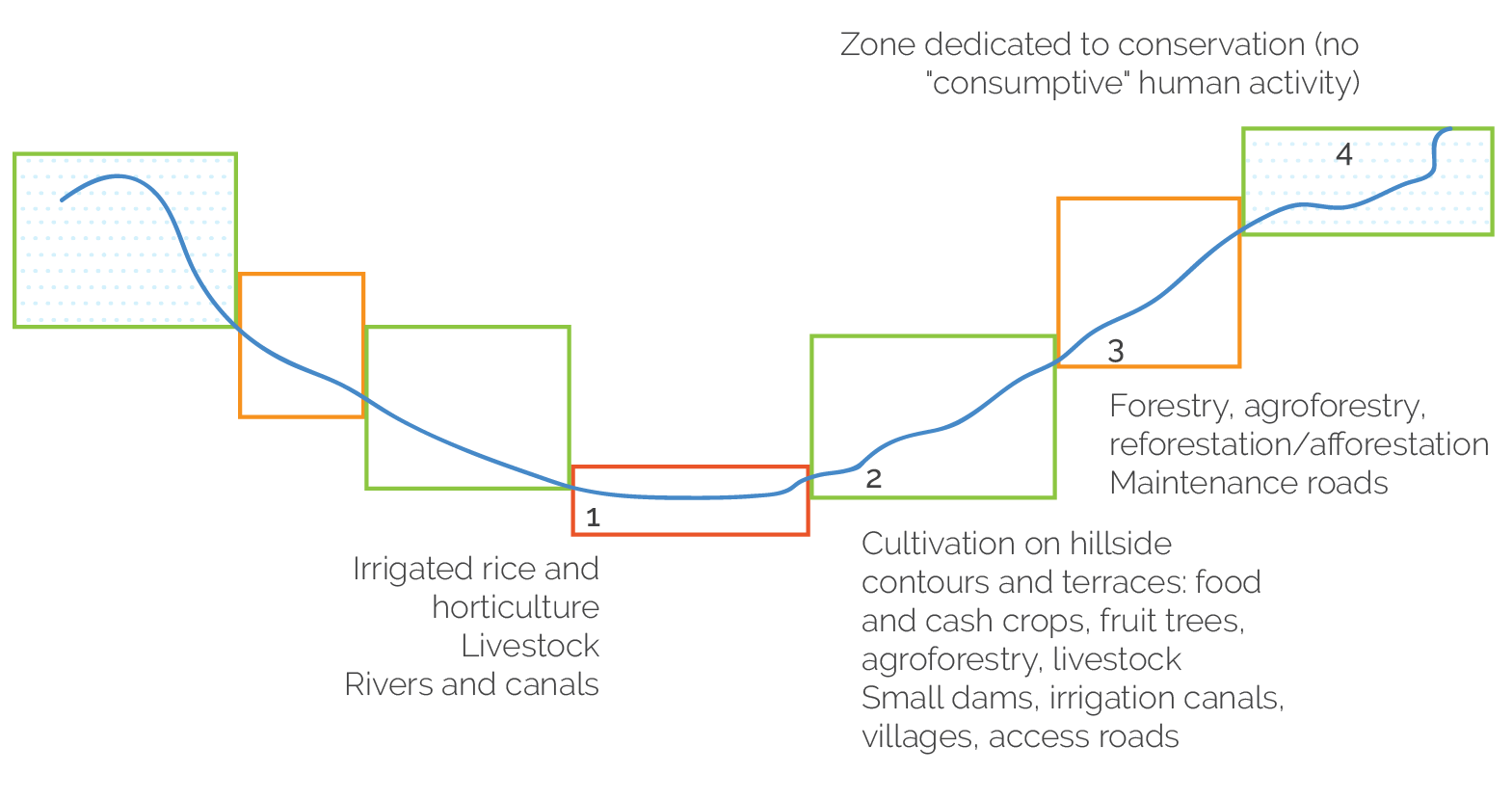

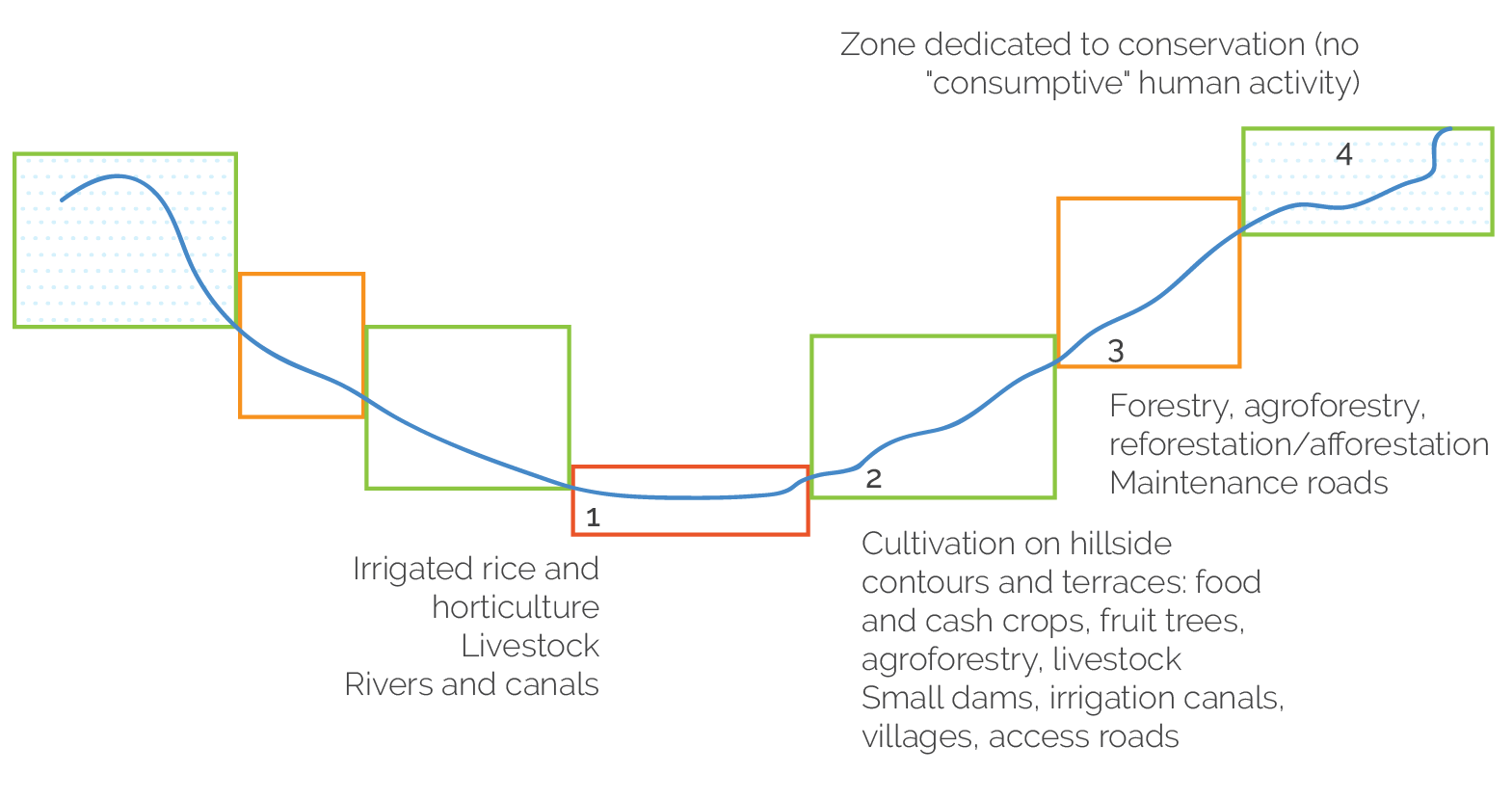

From 2018, the World Bank began to promote an integrated landscape management approach that integrates agricultural development and sustainable resource management into land use planning within a given area. This approach is currently being implemented by the Sustainable Landscape Management Project, active since 2019, that appears to be showing early signs of results at the household level. Under the project, a landscape is defined as the set of watersheds that are the source of water for a selected irrigation scheme. Four main land types are zoned within the landscape. The landscape approach identifies land uses within each land type (figure 5.1). The project identifies the key land users across the landscape and brings them together through a highly participatory process to prepare a land use management plan for the landscape. The project then finances priority productive investments within these land use management plans. It attempts to address lack of institutional coordination among key sectors by including three ministries responsible for planning for water, agriculture, and forests. Investments targeting downstream zones (zones 1, 2, and 3) aim to address constraints that contribute to low agricultural productivity and enhance the resilience of agricultural production systems. Investments targeting upstream zones (zone 4) support the management of critical ecosystems and protected areas. The project includes support to improve soil fertility to stabilize staple crop production around protected areas and pilots incentive-based conservation approaches that compensate communities for avoided deforestation.

Figure 5.1. Land Use within a Landscape—Profile of a Typical Valley

Source: World Bank 2017d.

Although this approach has several theoretical advantages for furthering rural development over the earlier support for protected areas management alone, it is too early to determine whether this new approach is producing results.2 Limitations of landscape management approaches reported in the literature that would need to be addressed to further rural development include approaches not necessarily addressing all actors involved in deforestation; for example, impoverished and landless migrants who clear land are often hired by richer farmers within a community to clear additional forest land. Lessons from EP3 and past agricultural productivity projects also point to the need to tailor the delivery of agriculture support to meet the needs and capacity of subsistence farmers. There is also a limit to what the agriculture sector alone can do to improve the livelihoods of the population in the forest frontier in a sustainable manner. Once basic food needs are met, households need to be provided with opportunities and a suitable business environment to diversify away from unsustainable agricultural practices.

Health, Nutrition, Social Protection, and Education

Between FY07 and FY21, the World Bank supported human capital development, targeting the health, education, and nutrition of rural Malagasy. Health, education, and nutrition support targeted vulnerable women and children living in remote and disadvantaged areas. Social protection targeted the poorest and food-insecure regions of rural Madagascar, promoting resilience through income-generating activities, reducing consumption poverty, and investing in human capital (for example, productive safety nets and conditional and unconditional cash transfers).

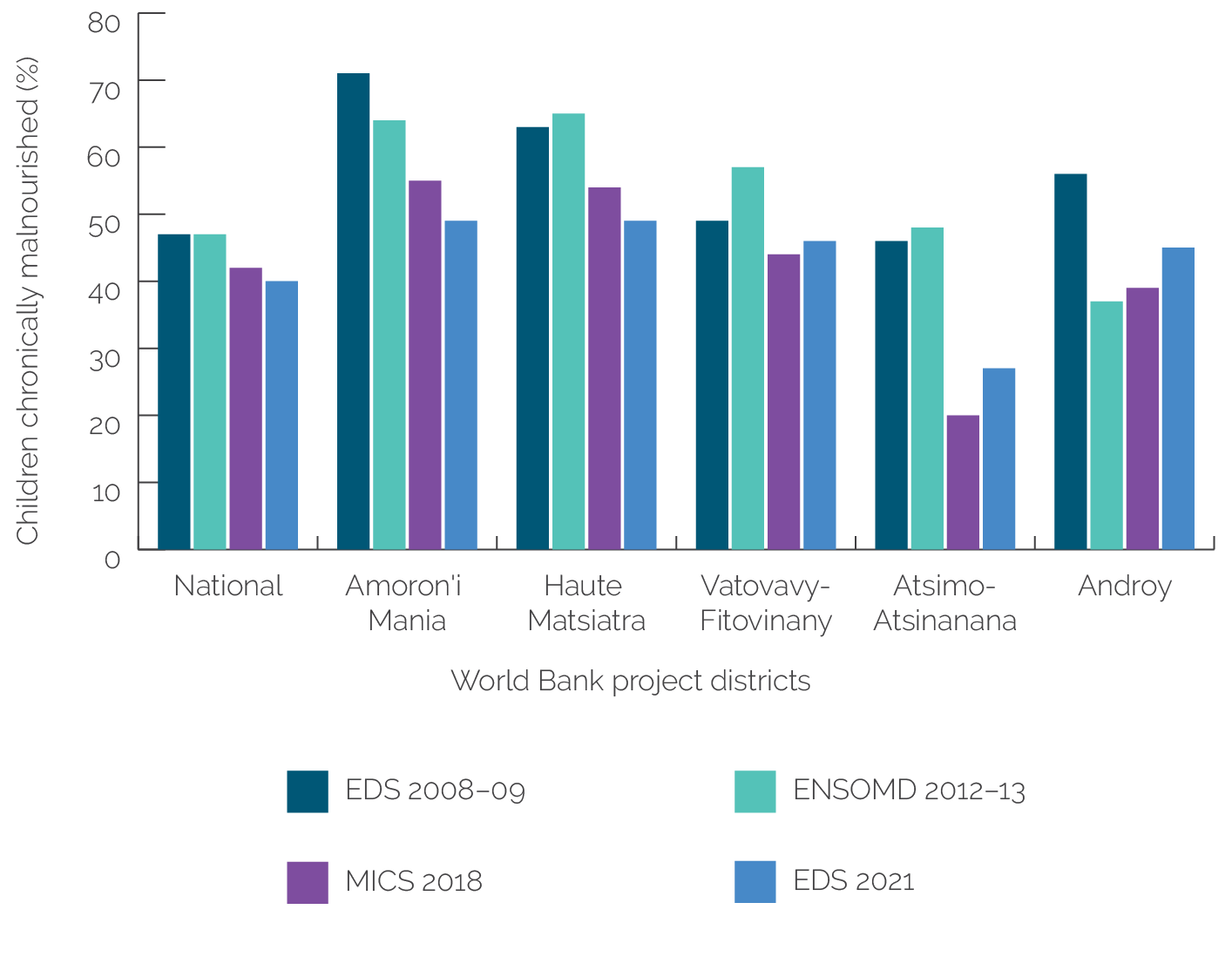

The World Bank contributed to tangible outcomes in nutrition by quickly adding or reallocating funds to respond to emergencies and crises. The Emergency Support to Critical Education, Health, and Nutrition Services Project provided emergency financing to bridge the funding gap and stop the deterioration in health, education, and nutrition outcomes that occurred during the period of World Bank (and other donor) disengagement during OP 7.30. The project contributed to a reduction in the rate of stunted growth among children under the age of five years in project regions. IEG upgraded the project rating from satisfactory to highly satisfactory after visiting Madagascar in 2019.3 Between FY13 and FY18, the national rate of stunted growth declined from 47 percent to 42 percent. Over the same period, project regions, which initially had rates much higher than the national average, declined at a faster rate than the national average (figure 5.2).

Figure 5.2. Chronic Malnutrition Rates, Children Five Years Old or Younger

Source: National Institute of Statistics.

Note: EDS = Enquête Démographique et de Santé de Madagascar (Demographic and Health Survey); ENSOMD = Enquête Nationale sur le Suivi des Objectifs du Millénaire pour le Développement (Madagascar National Survey on Monitoring the Millennium Development Goals); MICS = Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey.

World Bank engagement to improve education outcomes in Madagascar adapted in response to changing needs brought about by the political crisis. The political crisis curtailed government and donor financing for education, undermining the delivery of basic education services. Education projects were more successful in increasing access, with little progress made in improving student performance. Two World Bank projects (targeting different regions) provided emergency support, filling financing gaps, to maintain service delivery. First, the Emergency Support to Education for All Project supported preserving access to primary education and improving the teaching and learning environment. The project subsidized community teachers, built classrooms, and provided school kits and one meal per day to pupils to improve access and retention in primary education. The theory assumed that training schoolteachers and directors, subsidizing schools, enhancing school management, and building classrooms would improve the teaching and learning environment. The project targeted 12 of the most vulnerable regions, based on poverty and education indicators. The Emergency Support to Critical Education, Health, and Nutrition Services Project focused on preserving education service delivery in vulnerable areas, emphasizing access and affordability. Access to education increased in part due to the World Bank’s support, including the subsidizing of community teachers’ salaries, the training of nongovernment teachers and new recruits, the provision of school kits to primary school students, the provision of school grants to complement school funds from the government, the strengthening of decentralized technical services, the training of local communities in school management, the development of social accountability tools to improve community participation and transparency, the construction of classrooms, and the provision of school health and nutrition services (for example, providing medicines, vitamins, or meals in drought-affected regions).

Recent World Bank support prioritizes student learning, which is more likely to contribute to developing rural areas. Postcrisis, World Bank education interventions prioritized teaching and learning, while maintaining attention on access, attendance, and repetition and dropout rates. The Basic Education Support Project continued to support school management and teachers’ professional development; however, it also supported the professional development of school directors, the changing of the school calendar to accommodate agricultural seasons and weather cycles (both of which reduce attendance of teachers and students), and the changing of the language of instruction in the first two years (that is, increasing the use of first language instruction in the classroom). Regionally developed teacher training plans to improve early grade reading, writing, and mathematics supported central-level institution strengthening: preschool activity centers, public primary schools, and community-based early learning centers were supported through partnerships with local communities, CSOs, and private educational institutions to better prepare children for school. These results were reinforced by the Human Capital DPO, which, in the case of education, encouraged the government’s adoption of a merit-based approach to teacher recruitment and promotion, as well as reforms to the school grant formula.

World Bank support has contributed to significantly increasing enrollment in beneficiary areas. The 12 regions supported by the Emergency Support to Education for All Project experienced a 5 percent growth in enrollment rates in the three years before the start of the project, which was lower than in the rest of the country. For the period 2014–17, the growth of enrollment in the project’s regions was 3.85 percent annually, more than twice the annual growth rate in nonproject regions over the same period (1.9 percent) and in the rest of the country. Nationally, enrollment increased by 2.8 percent annually between 2014 and 2017.

The World Bank’s support to social protection directly contributed to reducing the prevalence of underweight children under the age of five years and increased food security. World Bank projects provided conditional and unconditional cash transfers to maintain Malagasy investments in human capital and provided productive safety nets (a cash-for-work, productive safety net, and human development cash transfer programs) to boost households’ income in the short term and invest in community assets to build resiliency (for example, microirrigation schemes, taking a landscape approach). The Second Community Nutrition Project (FY98–11) contributed to reductions in the rate of underweight children from 36 percent to 18 percent in target areas; long-term impacts of the community-based nutrition program were found for acute, but not chronic, malnutrition. The Emergency Support to Critical Education, Health, and Nutrition Services Project (FY13–14) contributed to food security by providing training and starter materials to vulnerable women so that they could start small-scale farming or small-scale husbandry. The grants contributed to improving the reliability and nutritional content of food sources and generating income. Women were found to invest their money, buying land, building houses, sending their children to school, and using health services.

The social protection system supported by the World Bank provided the means to respond to the COVID-19 crisis more quickly. During the 2009–14 crisis, the World Bank’s Emergency Food Security and Social Protection Project increased attention to targeting to ensure that those living in poverty benefited; this was done by targeting eligible beneficiaries for the cash-for-work safety net program. More recently, the Social Safety Net Project helped lay the foundation for a national social protection system; it was used to provide a rapid response to the poorest households affected by cyclones and floods. Its identification, targeting, and payment mechanisms have been used over the past two years to provide social safety nets to urban Malagasy more exposed to COVID-19.4

- International experience suggests that short-term support for intensified agricultural production is a first and necessary step to reduce the pressure on the forest and provide food security, but it is not sufficient to reduce deforestation. There is also a limit to what the agriculture sector alone can do to improve the livelihoods of the population on the forest frontier in a sustainable manner. Once basic food needs are met, households require opportunities and a supportive business environment to diversify away from unsustainable agricultural practices.

- The project’s Implementation Status and Results Reports track only the number of management plans signed, the area provided with irrigation, and the number of farmers adopting new production techniques. These indicators do not determine whether agricultural productivity is improving in an environmentally sustainable manner.

- Health, education, and social protection projects met or exceeded their targets. Eight out of nine closed projects were rated moderately satisfactory or better.

- In parallel, the Agriculture Rural Growth and Land Management Project provided social protection through emergency credits. The project was restructured during the pandemic: instead of financing regular agribusinesses and small to medium enterprises, it provided credits to keep businesses afloat (for example, to pay rent and salaries).