The World Bank Group in Madagascar

Chapter 3 | World Bank Group Portfolio in Madagascar, Fiscal Years 2007–21

Highlights

Following the triggering of Operational Policy 7.30 in 2009, the World Bank Group suspended disbursements and new commitments; lending operations were subsequently restructured to focus on the local level—an approach that the Bank Group maintained beyond the crisis period.

This pivot contributed to more effective project implementation in the face of political instability. By decentralizing implementation and management of projects, sectoral engagements were shielded to some extent from central-level political instability and state capture.

Despite the pause in lending, the Bank Group sought to maintain its influence during this period by shifting to nonlending activities and, in particular, analytical work on identifying and understanding the impact of political economy constraints on portfolio performance.

The International Development Association’s Turn Around Allocation contributed to increasing the government’s commitment to address the country’s development constraints. It also provided a platform for dialogue with development partners.

World Bank leadership was crucial to reengaging donors and building momentum for recovery after the political crisis. However, collaboration with civil society organizations was ad hoc and mostly consultative, missing the opportunity to leverage support for the implementation of reform.

Lending and Nonlending

Lending

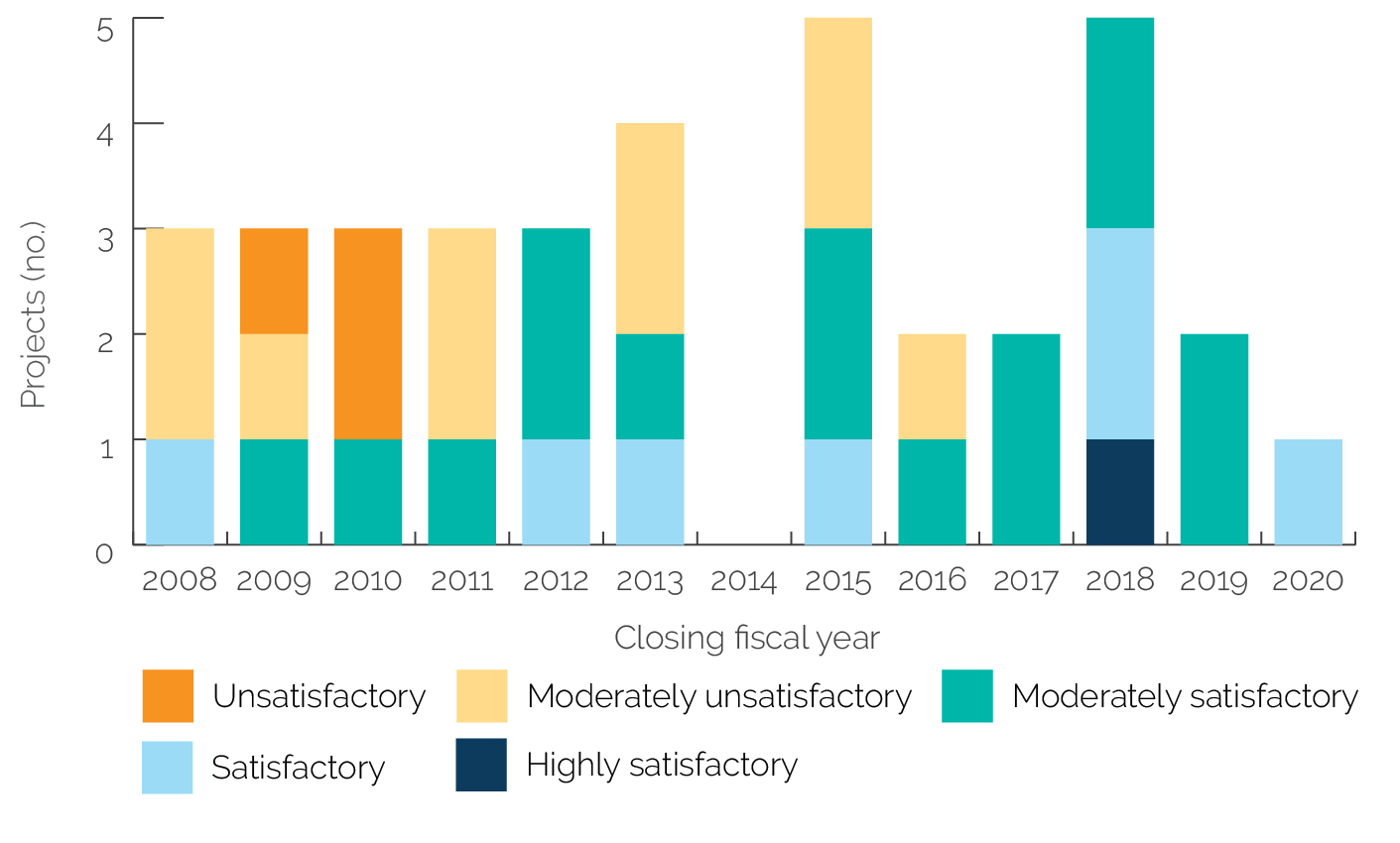

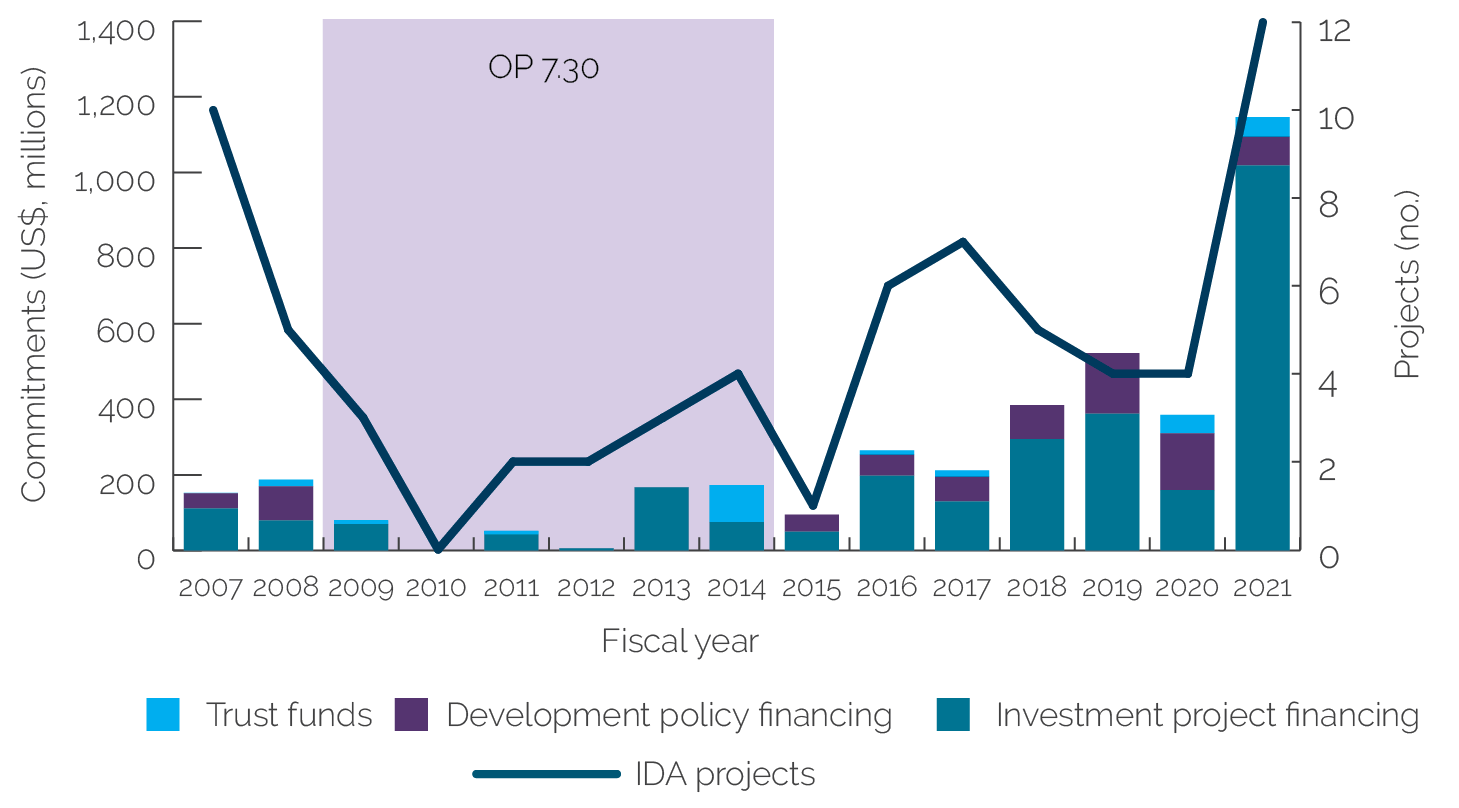

Bank Group commitments to Madagascar amounted to $2.9 billion over FY07–21. The Bank Group–supported program included (i) $2.7 billion in IDA grants and credits, of which $1.7 billion was investment project financing, $700 million was development policy financing, and $220 million was trust fund financing; (ii) $122 million in International Finance Corporation (IFC) investments, including long-term financing, swaps, and rights issues; and (iii) $107 million in Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) maximum gross exposure at issuance. (See figure 3.1.)

In line with strategy evolution, projects under implementation at the time of the political crisis were restructured to focus on the local level.1 Examples include providing grants to communes, supporting the strengthening of government grant transfer and equalization mechanisms to communes, building revenue collection and management capacity at the local level (with a focus on mineral and natural resources), and deepening partnerships with civil society organizations (CSOs) to support social accountability for improved service delivery at the local level (box 3.1).

Figure 3.1. New Commitments to Madagascar by Financing Mechanism, Fiscal Years 2007–21

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: IDA = International Development Association; OP = Operational Policy.

Box 3.1. Examples of the World Bank’s Pivot to Local-Level Engagement

Several projects were restructured during the 2009–14 political crisis, expanding the roles of local and nonstate actors:

- The Second Governance and Institutional Development Project—the World Bank’s flagship governance project during the political crisis—was restructured in 2012 to provide grant support to decentralized entities and civil society organizations at the commune level to support participatory budgeting and strengthen the capacity of accountability institutions, such as observatories and the ombudsman, to monitor reform implementation.

- Additional financing for the Third Environment Program Support Project was provided to help maintain conservation support in protected areas and support for project-affected people. The additional financing was designed to enhance the involvement of the national parks and international conservation nongovernmental organizations and aimed to provide livelihood support for local communities. This included support for community development activities, such as community forestry management groups.

- The Integrated Growth Poles Project was restructured to shift project management and decision-making to the local level. The national steering committee was replaced with several regional steering committees that included municipal and regional authorities and private sector representatives. The shift helped strengthen ownership as a result of the greater proximity to day-to-day implementation, enabling the project to surpass outcome targets for job creation, business registration, and project beneficiaries. The approach was strengthened in the follow-up Integrated Growth Poles and Corridor Project 2, which supplemented the central project implementation unit with decentralized technical units in each regional pole. The project strengthened the focus on building local government capacity and anchoring the project locally. Outcomes were substantial: annual municipal revenues in the target poles increased by several billion ariary, thousands of tourism and agribusiness jobs were created in the target poles (more than 4,000 in tourism and more than 8,000 in agribusiness), and thousands of businesses were registered (more than 3,000 in tourism and more than 2,000 in agribusiness; World Bank 2015c). For both projects, strong implementation arrangements were partially credited for the projects’ success: the Independent Evaluation Group rated the World Bank’s performance as moderately satisfactory for the first project and satisfactory for the second.

Although the pivot to the local level helped the World Bank achieve sustainable results, it was not universally successful.

- Community development and safeguard activities included in additional financing for the Third Environment Program Support Project were “poorly designed and underfunded” and did not result in improved community livelihoods (World Bank 2021d, 54). According to the Project Performance Assessment Report, community development activities were “not tailored to the needs of local communities and documented low satisfaction by beneficiaries” (World Bank 2021d, 27). The same report noted that “the use of nonrepresentative local institutions allowed local elites to influence decision-making, and social safeguards can hence exacerbate social inequalities instead of addressing them” (World Bank 2021d, 28).

Sources: World Bank 2015c, 2015d, 2016b, 2021d.

This pivot contributed to more effective implementation across several projects in the face of political instability and elite capture. By decentralizing implementation and management of projects, sectoral engagements were shielded to some extent from central-level political instability and elite capture. This translated into improved project results in some cases, with some exceptions (box 3.1).2

Bank Group support rebounded in FY16, fueled by additional IDA financing through the Turn Around Regime and, later, the TAA. By reorienting the strategy to directly address fragility drivers, Madagascar was able to double its IDA performance-based allocation, from $110 to $230 million per year during the 17th and into the 18th IDA Replenishments, through a total additional $1.35 billion from the TAA.

The pivot to the local level manifested itself in both lending and nonlending portfolios. Political economy analysis helped identify the incentives of different government actors in the Public Sector Performance Project (World Bank 2016a), which were then aligned in a project context, using disbursement-linked indicators (now, performance-based conditions). Examples include removing intermediaries from the processing of tax payments and introducing performance management in the customs authority to increase the identification rate of suspicious customs transactions. Political economy analysis on tax and customs administration reform contributed to an increase in the rate of intercepted suspicious customs transactions for the Toamasina port from 5 percent to 26 percent (surpassing the initial target of 12.5 percent). As part of the scale-up in budget support from FY14 onward, the reengagement development policy operation (DPO) included prior actions on the filing of ministerial asset declarations.3 This led to an increase from 20.5 percent in 2013 to 100 percent in 2015 in the share of cabinet ministers filing asset declarations with the Independent Anticorruption Bureau (Bureau Indépendant Anti-Corruption). Additionally, analytical work helped make the case for fiscal decentralization, focusing on reducing geographic inequities in funding at the subnational level. This was reflected in the Inclusive and Resilient Growth DPO, which had a prior action requiring publication of all planned and executed transfers to local governments.

The TAA strengthened government commitment to reform while providing a platform for dialogue with government and development partners. Increased financing from the TAA helped the World Bank, through a series of DPOs and with other multilateral assistance, to “help…avert a potential social crisis” (World Bank 2020a, 24). According to Demetriou (2019), Madagascar achieved substantial progress in (i) establishment of democratic institutions, (ii) macroeconomic stability, (iii) increased revenue mobilization, and (iv) implementation of priority public financial management reforms; it achieved moderate progress in (i) reform of the security sector, (ii) decentralization, (iii) fight against elite capture, (iv) strengthening of checks and balances, (v) tightening of SOE management, and (vi) private sector development and sectoral productivity; it made inadequate progress, however, in (i) national reconciliation and (ii) social services.

In line with other development finance institutions, IFC and MIGA limited new investments during the political crisis (2009–14). Over the evaluation period, support amounted to $105 million in IFC investments, including long-term financing, swaps, and rights issues, and $107 million in MIGA gross exposure at issuance. IFC’s 10 investments were in financial markets (or access to finance), agribusiness, infrastructure, and the telecoms sector. IFC also provided a short-term guarantee of $178 million as part of the Global Trade Finance Program. During the crisis, IFC undertook one loan in the poultry sector and rights issuance to two financial sector investments in the commercial banking sector and the microcredit sector. MIGA’s 13 guarantees covered services, infrastructure, and tourism and centered on power generation and airport infrastructure.

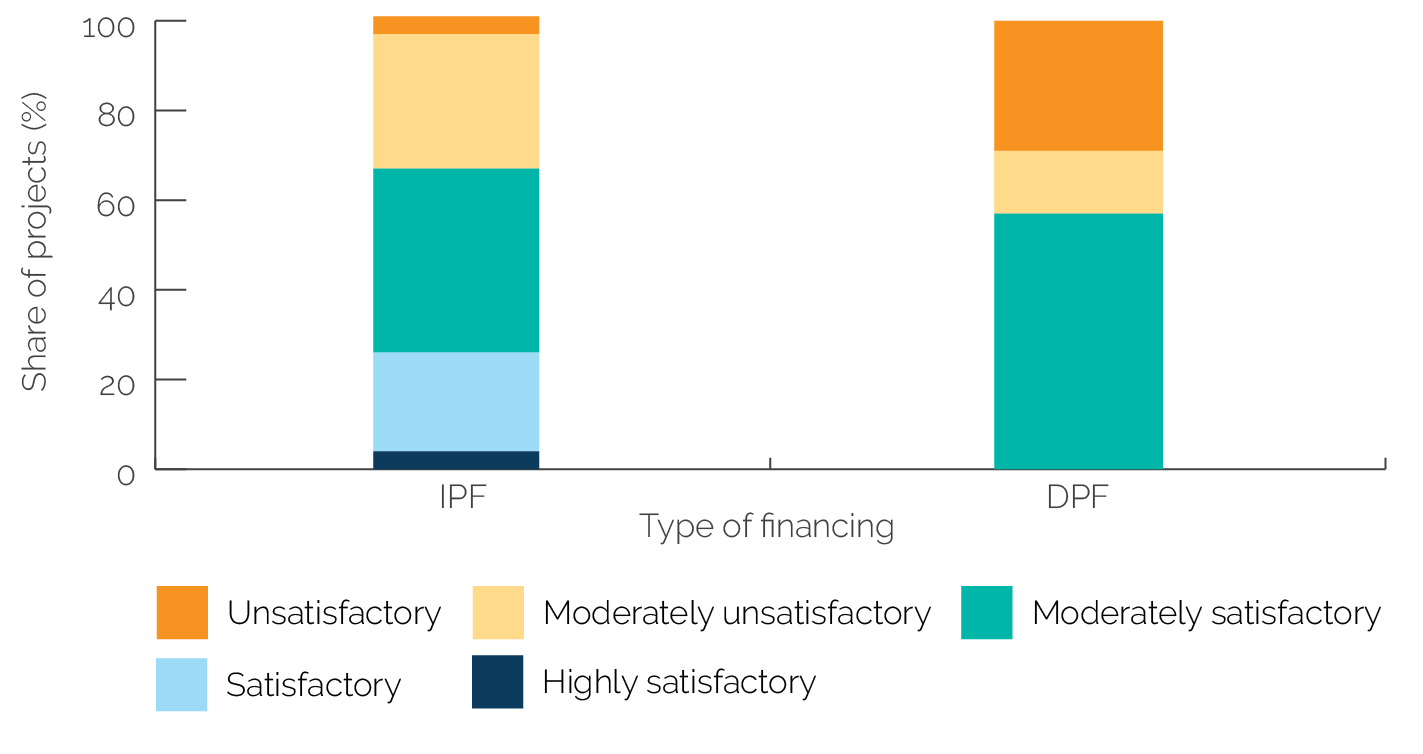

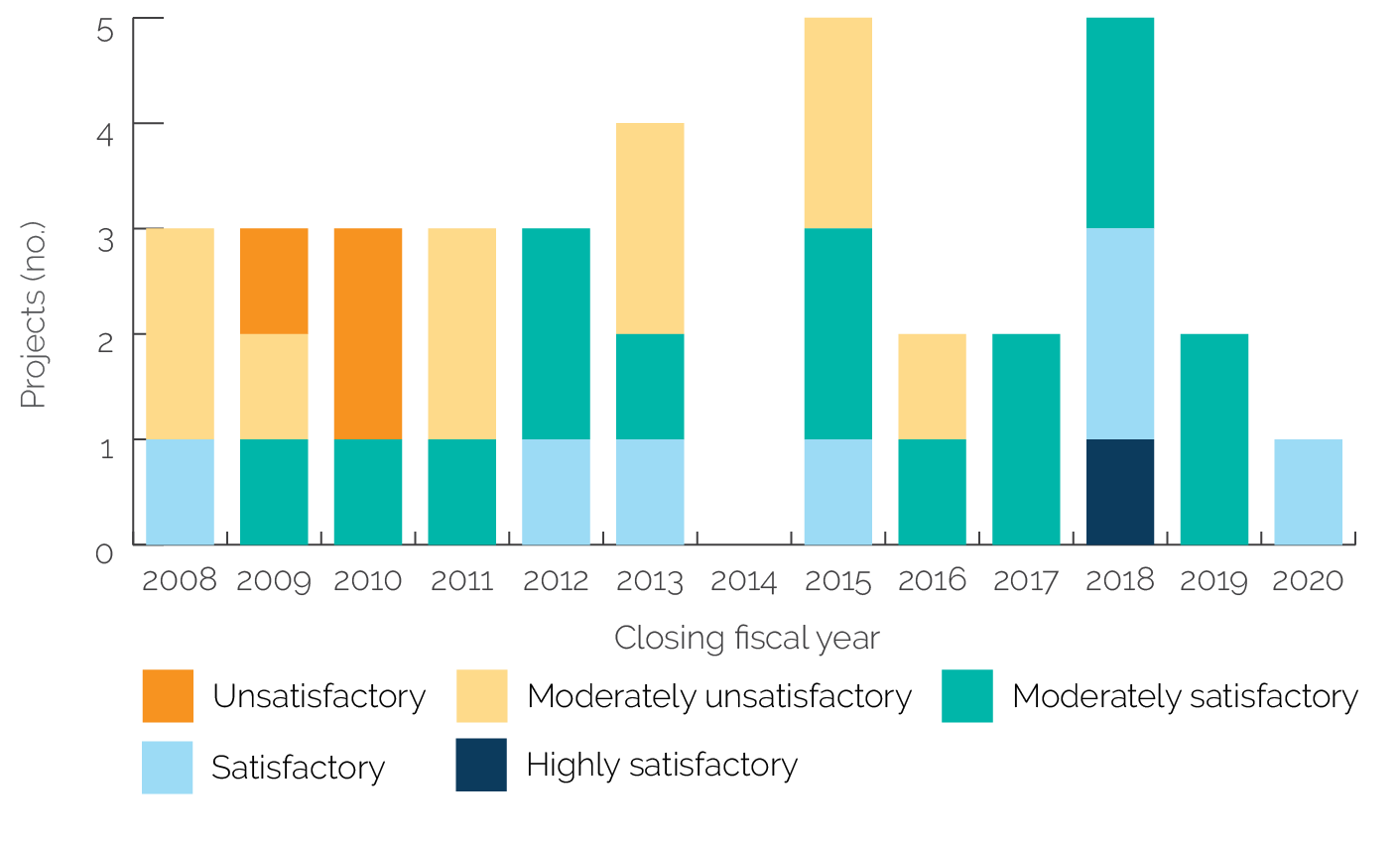

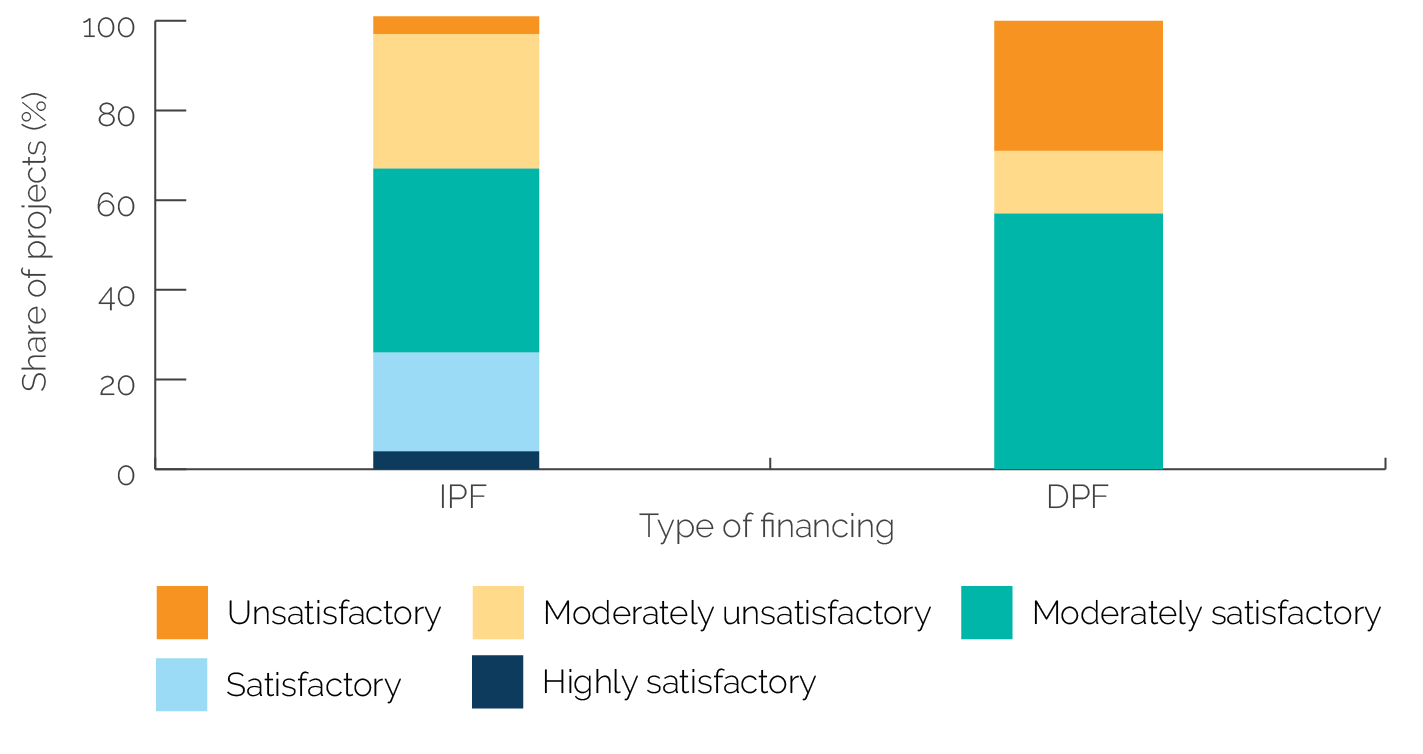

World Bank projects that closed after the crisis had a better track record of achieving their targets and objectives than those closing before and during the crisis. The crisis complicated implementation of the World Bank’s portfolio across the board, triggering a portfoliowide restructuring and the closing of several projects. In recognition of this, the World Bank’s Completion and Learning Review rated achievement of all three ISN objectives as unsatisfactory. Outcome ratings for projects closing after the political crisis were rated higher on average. Outcome ratings for all projects closing after FY16 were rated at least moderately satisfactory (figure 3.2). The highest outcome ratings were for emergency projects—developed in the later years of the crisis to support education, health, nutrition, food security, social protection, and private sector development. Although the projects were relevant to the crisis-related challenges facing Madagascar at the time, their objectives were more short-term in nature and therefore less commensurate with the intractable development challenges the country had been facing. The poorest outcome ratings were for governance projects implemented before and during the political crisis and for budget support operations approved before the crisis. Overall, investment projects performed better on overall outcomes than development policy financing over the evaluation period (figure 3.3).

Bank performance ratings were consistently favorable over the evaluation period, except for two early governance projects. Of the 27 investment projects that closed between FY07 and FY21, 9 had Bank performance rated satisfactory by IEG, 15 were rated moderately satisfactory, 2 were rated moderately unsatisfactory, and 1 was unsatisfactory. Two of the three most poorly rated projects were governance projects: Governance and Institutional Development Project I and Governance and Institutional Development Project II. In reviewing Bank performance for both projects, IEG cited as reasons for the low ratings (i) shortcomings in design or overly ambitious design and (ii) insufficient engagement with stakeholders (which led to weak government ownership); these lessons were successfully applied to the follow-on governance project, the Public Sector Performance Project (box 4.1), whose most recent self-ratings on progress toward achievement of development objectives and overall implementation progress were moderately satisfactory (World Bank 2021b).

Figure 3.2. Project and Operation Outcome Ratings, by Closing Fiscal Year

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Figure 3.3. Overall Outcome Ratings: Investment Project Financing versus Development Policy Financing Approved since 2007

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: DPF = development policy financing; IPF = investment project financing.

Nonlending

The Bank Group implemented a substantial program of ASA work on Madagascar. Nonlending support included 17 IFC advisory services (client facing or market and client development operations, mostly in financial markets, agribusiness, and infrastructure) and 116 World Bank reports. Although nonlending support continued to be delivered throughout the political crisis, the number of ASA products declined from FY09 to FY13, with ASA work scaling back up alongside the World Bank’s reengagement in FY14 and FY15.

ASA played a critical role in helping the World Bank remain relevant during the political crisis, when lending was curtailed and meetings with the government were limited to the technical level. Starting in 2010 with a series of Policy Notes, the World Bank scaled up ASA activities under the ISN, with a strong emphasis on governance and political economy. The first series, written shortly after the Bank Group froze disbursements and halted new lending, took stock of the situation in critical sectors (World Bank 2010b). The second was written shortly before lending resumed, with the lifting of OP 7.30 (World Bank 2014c). Both directly influenced the World Bank’s technical discussions with the client and informed project design for when the World Bank restructured its lending portfolio.

The analysis of political economy constraints directly influenced the World Bank’s lending portfolio. ASA provided a road map for how the World Bank could mainstream governance support across its portfolio, including in natural resource management (mining and forestry) and other sectors:

- In natural resource management, World Bank support helped develop legal, regulatory, fiscal, and institutional frameworks for the effective and transparent management of natural resources and revenues and boosted local capacity to manage revenues from mining operations.

- In health, problem-driven applied political economy analysis (World Bank 2019) led the World Bank to integrate within the Human Capital DPO measures to support direct transfers of budget allocations from the Ministry of Public Health to the commune level (which led to the piloting of a project funded by the Global Partnership for Social Accountability [GPSA] for citizen health management monitoring).

- In private sector development, analysis of corruption and elite capture—including an influential internal analysis of the private sector from 2016 (World Bank 2016c)—contributed to IFC’s decision to use preemptive integrity due diligence screening on preidentified local companies and conglomerates active in sectors of interest. IFC’s preemptive due diligence screening was undertaken to expand business in the challenging context of elite capture and help inform the viability and soundness of the IFC country strategy, which identified textile, tourism, and agribusiness as strategic sectors for the country. The integrity due diligence screening resulted in a vetted list of key local players in these sectors of interest to aid in generating a new investment pipeline and validate the existing pipeline in other sectors. The recently published Country Private Sector Diagnostic extended the World Bank’s political economy analysis of the private sector; it identified “deep-rooted governance issues (especially as they relate to policy unpredictability, red tape, and the uneven playing field in key sectors of the economy)” as the primary constraint affecting private sector participation (World Bank Group 2021a).

Integrating Gender Sensitivity

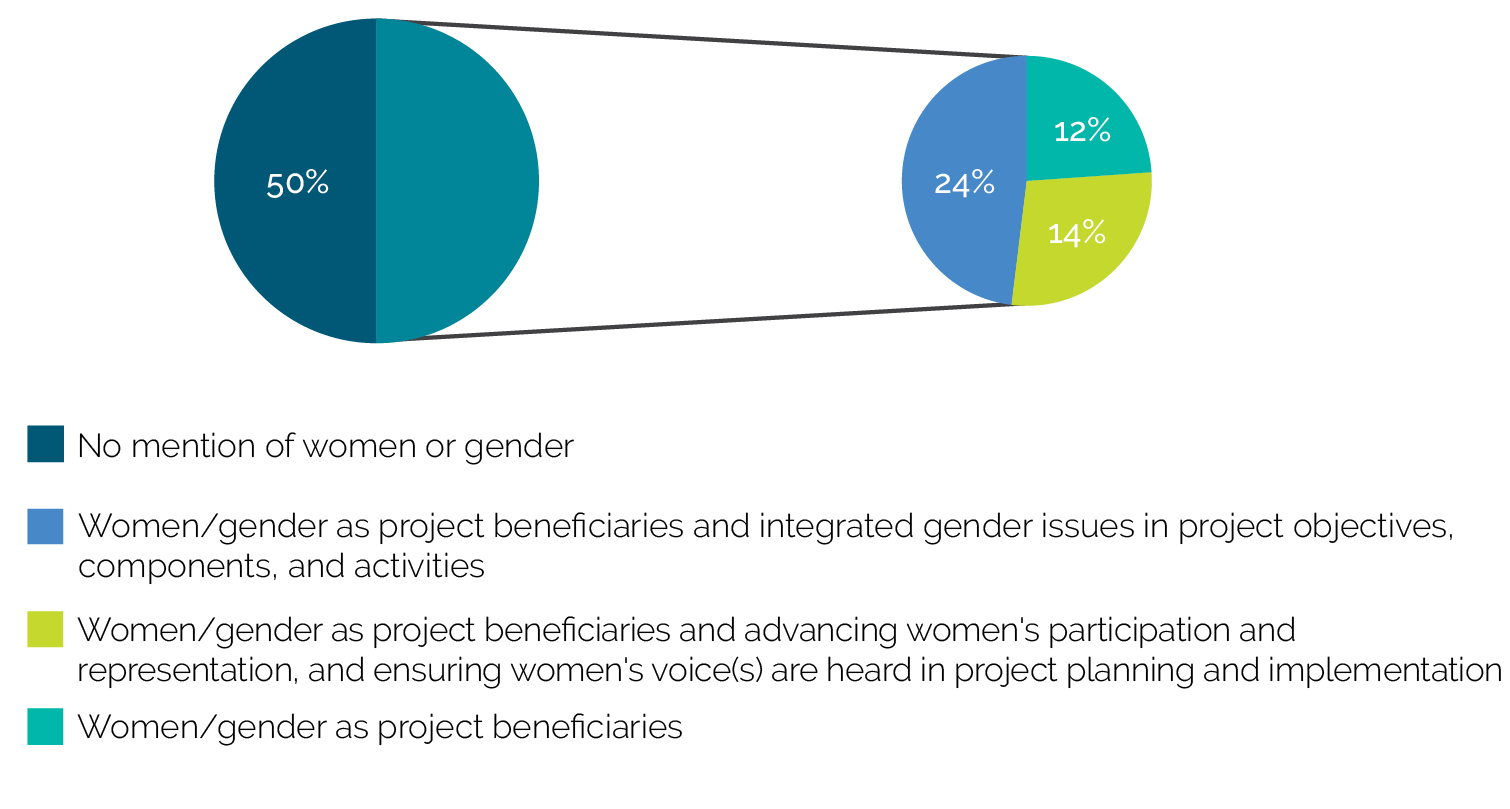

The Bank Group was only partially successful in integrating gender into project design. Although addressing gender gaps is a corporate commitment of the Bank Group and country strategies have identified major gender issues that have impeded rural development and governance in Madagascar, half of the portfolio of Bank Group projects did not mention gender at all in their design. (However, 80 percent of human development projects [11 of 13] mentioned gender.) Of the 25 projects that mentioned gender, about half went beyond the mere disaggregation by sex of results indicators. Most of the projects that did not mention gender concerned macrofiscal objectives (5 of 6 projects), public sector governance (5 of 9), and private sector development (4 of 7; figure 3.4). IFC included gender-focused activities in several investments, including the BoViMa advisory engagement, and, like the World Bank, increasingly tracks gender-disaggregated indicators.

World Bank projects in Madagascar have increasingly integrated gender into project design, including by identifying and addressing the unintended consequences of projects. More recent projects have been targeted in terms of gender interventions, for example by including support for the promotion of legal reforms to combat GBV in the human capital development policy financing or by addressing the gendered dimensions of poverty, fragility, and insecurity (that is, looking not only at women but also young men) under the Support for Resilient Livelihoods project.

Figure 3.4. Breakdown of Projects Mentioning Gender (percent of total)

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Coordinating with Partners

Over the evaluation period, the World Bank coordinated well with development partners. Through the increased allocation of IDA resources from the TAA, the World Bank catalyzed development partner reengagement (World Bank 2019). The World Bank coordinated particularly well with partners active in governance. It participated actively in the Public Financial Management Donor Coordination Working Group, the Partnership Agreement (which coordinated budget support providers and the government), and the Decentralization Donor Coordination Working Group. An informal agreement with the European Union (EU) after the political crisis on a division of labor had the World Bank responsible for supporting revenue generation while leaving much of the expenditure-related work to the EU.

There was ad hoc consultation with CSOs working on public financial management. Several CSOs active in the accountability space noted that engagement with the World Bank had been more systematic in the earlier years of the evaluation period and expressed the view that, since reengagement, the World Bank had only involved them in consultations. The World Bank’s Extended Governance and Anticorruption Review of 10 then-active projects found little strategic engagement with CSOs and other nonstate actors (World Bank 2015a). This could be partially explained by the limited capacity of Malagasy CSOs and their concentration in the capital. However, over the past several years, their capacity and geographic reach have improved, but collaboration remains limited.

World Bank coordination with partners was strong in the forestry sector, but less so in the broader agriculture sector. The World Bank actively coordinated with the principal development partners in forestry. This included the French Development Agency, the EU, the German Agency for International Cooperation, and the United States Agency for International Development. Throughout its support of the National Environmental Action Plan, the World Bank partnered closely with conservation nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and participated in the early stages of the donor coordination committee. It also partnered closely with the French Development Agency as a co-financer of projects and regularly participated in sector donor platform meetings, alongside the Ministry of Agriculture. Coordination with development partners was less apparent in the fisheries sector, with some donors pointing to the need for greater coordination to avoid overlap and duplication, given the proliferation of donor-funded projects. Although the World Bank is one of four main donors in agriculture, alongside the African Development Bank, the International Fund for Agricultural Development, and the EU, it was seen by some partners as not always willing to share information, particularly in relation to the preparation of new projects.

- These operations did not include development policy lending, which was suspended during the World Bank’s disengagement.

- This is in contrast to the Rural Development Support Project, which did not significantly shift its approach (the project was late into its implementation, with a planned end date of fiscal year 2011) and was less successful at maintaining results during this complicated period: “as a result of its national presence, the project was pulled in different directions to address the challenges arising from the external shocks” and thus failed to achieve a “catalytic effect” on rural development (World Bank 2013b, 19).

- Although filing alone is not sufficient, reviewing declarations to verify accuracy and then publishing them to enhance accountability is considered good practice.