The World Bank Group in Madagascar

Chapter 2 | World Bank Group–Supported Strategies for Madagascar, Fiscal Years 2007–21

Highlights

World Bank Group–supported strategies adapted over time in response to the changing country context, including, critically, the political crisis of 2009–14.

The Bank Group correctly identified key bottlenecks that limited inclusive growth and poverty reduction in Madagascar. Its portfolio increasingly reflected the importance of addressing weak governance and limited rural development.

The triggering of Operational Policy 7.30 engendered a pivot in the Bank Group’s approach, leading to a focus on the local level and drawing more directly on nonstate actors, which allowed for continued engagement amid—and after—political instability.

The International Development Association fragility, conflict, and violence allocation expanded the Bank Group’s influence and ability to support Madagascar. The Turn Around Allocation’s requirement that a country make meaningful progress in addressing its fragility drivers (weak governance, in Madagascar) enabled the Bank Group to address critical binding constraints more explicitly.

Evolution and Adaptation of the World Bank Group’s Approach

Over the evaluation period, the Bank Group increasingly identified correctly the key bottlenecks that drove fragility and limited inclusive growth and poverty reduction in Madagascar. These constraints—weak governance and limited rural development—remained throughout the evaluation period and were reflected across Bank Group–supported strategies for Madagascar. Governance and rural development are interconnected and cross-cutting constraints, touching multiple sectors. Governance includes transparency, accountability, and citizen participation; domestic resource mobilization; public expenditure management; and decentralization, including the enabling environment for service delivery. The Bank Group–supported strategies sought to (i) increase fiscal space (through greater domestic revenue mobilization) to allow for greater spending on priority and social sectors to improve public service delivery; (ii) strengthen the role of, and resources available to, local governments; and (iii) improve government transparency and accountability and reduce corruption, particularly in the natural resources, education, and urban development sectors. Support for rural development (that is, improving livelihoods and the quality of life of people living in rural areas) is multidimensional and multisectoral. It included agriculture, natural resources, and the environment; human capital development; connectivity infrastructure; access to basic services (for example, health, education, social protection); and food security.

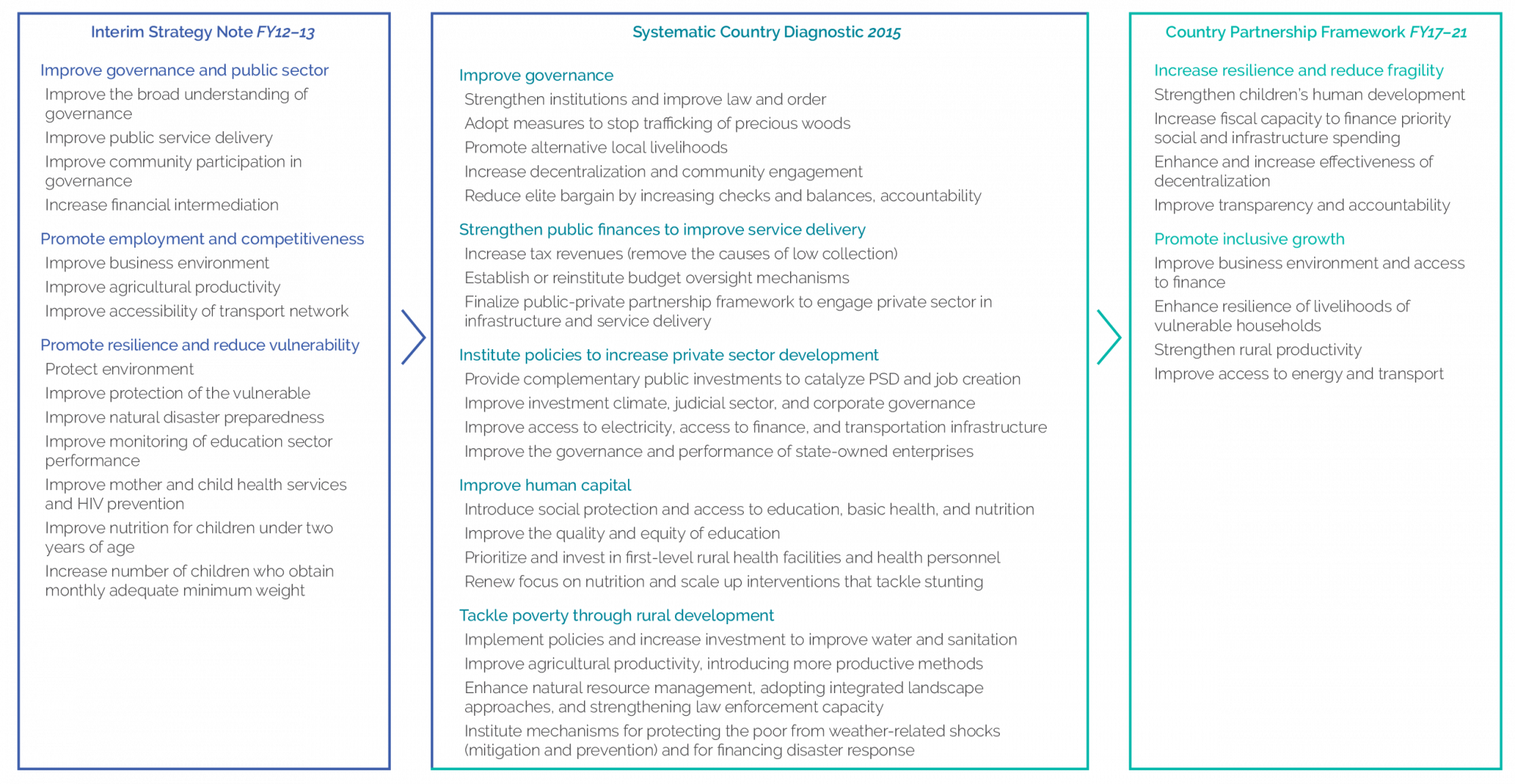

Three strategies guided Bank Group support during the evaluation period. These were the Country Assistance Strategy (CAS) for FY07–11, the Interim Strategy Note (ISN) FY12–13, and the Country Partnership Framework (CPF) FY17–21. Appendix A presents the strategic objectives of these strategies in detail. Appendix B illustrates the alignment between the government’s objectives and Bank Group objectives. Figure 2.1 presents a flowchart showing how the objectives of the ISN, SCD, and CPF fit together.

Prepared when economic growth was relatively strong, social indicators were improving, and poverty was declining, the FY07–11 CAS was ambitious and covered a wide range of development challenges. The CAS was built around two pillars: (i) removing key bottlenecks to investment and growth in rural and urban areas, and (ii) improving access to, and quality of, services. To support the government’s Madagascar Action Plan, CAS interventions included support to private sector development (including access to finance and reducing regulatory burdens), infrastructure (transportation, energy, and infrastructure supporting agricultural productivity and diversification), domestic resource mobilization, primary education, and child and maternal health and nutrition. The World Bank extended the Poverty Reduction Support Credit cycle to provide regular budget support, sustain sectorwide approaches, promote public-private partnerships and guarantees for infrastructure, and support institutional and capacity building (World Bank 2007). Although the Madagascar Action Plan was widely praised by the World Bank and other development partners at the time, in hindsight it was overly broad and insufficiently prioritized—shortcomings that were reflected in the CAS (FY07–11).

The political crisis in early 2009 disrupted implementation of the CAS and triggered a temporary suspension of disbursements and new commitments by the Bank Group. The unconstitutional change of government triggered the Bank Group’s Operational Policy (OP) 7.30, on dealing with de facto governments, which led the Bank Group to pause all lending to Madagascar (box 2.1). In late 2009, disbursements for five projects resumed on “humanitarian and safeguard grounds,” and in May 2010, an exception was granted to resume disbursements for more projects, partly to permit the government to pay arrears and to fund project implementation units. In 2011, as the country made efforts to restore a constitutional government, IDA adopted an ISN, restructured all active projects, and resumed implementation of existing projects. The resumption of lending was partly motivated by the sharp increase in the share of the population living in poverty between 2008 and 2013 (up by more than 10 percentage points).

Madagascar’s 2009 political crisis engendered a recalibration of the Bank Group–supported strategy because of the direct impact that governance shortcomings were having on its portfolio. The political crisis was largely unanticipated and triggered a ramping up of analytical work by the World Bank to better understand the causes of political instability. Starting with the ISN, a concerted effort was made to better understand the risks and determine how to adapt World Bank operations to political economy constraints. Following the restoration of constitutional order, the World Bank continued to prioritize such analysis, including through fragility assessments and a forthcoming risk and resilience assessment on southern Madagascar (Pellerin 2014; World Bank 2021c).

Box 2.1. Madagascar’s 2009 Political Crisis and the Triggering of Operational Policy 7.30

In February 2009, army dissent led to an unconstitutional transfer of power. This move was broadly rejected by the international community and led to sanctions being placed on the de facto government by the African Union and others. Political turmoil continued, as power-sharing deals collapsed, and countercoups were attempted.

In response, in March 2009, the World Bank Group triggered Operational Policy 7.30 on dealing with de facto governments. This involved the immediate suspension of disbursements on existing loans and no new lending, resulting in the country using less than a quarter of its 15th Replenishment of International Development Association allocation of approximately US$600 million. Most bilateral and multilateral donors temporarily halted or scaled back development assistance at the same time.

Portfolio disbursements were progressively resumed beginning in December 2009 to “attend to the plight of the most vulnerable segments of the population” (World Bank 2011b, 14). An exception to new lending was granted in June 2011, for additional financing to the World Bank’s environment program, on the grounds that “its unique global public good and substantial social safeguard risks [are] linked to the end of the current financing.” New lending of US$18 million was later allowed for emergency projects (in health and for urgent repairs to cyclone damage), using savings from projects that were closed during the portfoliowide restructuring. Overall, the World Bank’s portfolio shrank from 20 active projects in FY09 to 7 by FY14.

Madagascar’s status under Operational Policy 7.30 was lifted in 2014, after the return to constitutional order.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

The ISN acknowledged the World Bank’s earlier failure in monitoring political economy dynamics and the negative impact this had had on portfolio performance. It noted, “more vigilance may have been needed when the signs of governance deviations and the risks of conflict of interest were becoming increasingly apparent, eventually causing the crisis” (World Bank 2011b, 17). This shift took hold with the launch of an advisory services and analytics (ASA) program under the ISN, “which included highly relevant and much needed political economy analysis” (World Bank 2017a, 65).

The Bank Group’s interim strategy for FY12–13 focused on addressing Madagascar’s immediate needs in the context of extreme political, social, and economic instability. According to the ISN, this required addressing the root causes of the political crisis, boosting the resilience of the most vulnerable, and fostering job creation. At the time, the country was becoming more fragile because of the ongoing political crisis and deteriorating security situation. The situation was particularly dire for health, education, and food security, given the partial collapse of the country’s public service delivery system. The ISN focused on (i) improving governance and public sector capacity (for example, improving public financial management, building social accountability in mining areas and enhancing transparency in the management of the sector, and strengthening land tenure); (ii) addressing basic health services (including HIV/AIDS and nutrition) and disaster risk reduction (including addressing the most urgent repairs from cyclone damage and supporting risk reduction activities in vulnerable areas); and (iii) improving access to small and medium enterprise finance and microfinance, promoting private sector investments in poor areas (including through the restructuring of the telecom public-private partnership), and improving support for artisanal and small-scale mining activities in the south and elsewhere (World Bank 2011b).

The Bank Group’s approach to working with Madagascar adapted to the evolving political economy and addressed governance constraints by pivoting engagements to the local level. There was a tangible shift across strategies in the Bank Group’s approach, with the 2009 political crisis being a watershed moment. Although the CAS (FY07–11) took a centralized, top-down approach (that is, focusing on central-level reforms, such as strengthening systems and budget preparation and execution processes), the ISN (FY12–13) emphasized “decentralized systems and community-based interventions,” including the rollout of social accountability mechanisms (for example, community scorecards and participatory budgeting) at the local level. In a departure from the CAS, the ISN emphasized the need for a stronger role for civil society and the media in implementing programs, as well as “a sounding board to leverage policy changes and reforms.” This bottom-up approach continued to some extent with the CPF, which prioritized reinforcing the capacity of local administrations to deliver services and recover and manage revenue in a more transparent and accountable way.

The return to constitutional order in 2014 led to a restoration of Madagascar’s relations with the Bank Group and other donors. Democratic institutions and political stability were restored, thanks in large part to the Roadmap to Peace brokered by the Southern African Development Community. Macroeconomic stability improved, and growth rose. Critically, OP 7.30, which had been in effect since March 2009, was lifted in 2014, allowing the Bank Group to fully resume lending. However, given the disruptive nature of the political crisis, including the broad slippage in development gains that occurred during this period, the Bank Group sought to reengage differently.

The CPF FY17–21 sought to leverage the World Bank’s portfolio to address the structural causes of the country’s fragility. This was an important development given earlier avoidance of some politically sensitive areas of engagement. Drawing on political economy analysis (box 2.2), the CPF was anchored in the country’s main fragility drivers: (i) elite capture, (ii) social fragmentation in the context of a centralized state, (iii) weak governance of natural resources, and (iv) nascent checks and balances (World Bank 2017a, 3). The CPF noted that “overcoming fragility—a sine qua non for reducing poverty in a lasting way—requires consolidating political reconciliation and rebalancing the power between a strong central state and the decentralized structures” (World Bank 2017a, 4); these are core elements of the government’s postcrisis strategic development plan, the 2015–19 National Development Plan. The first of the CPF’s two objectives, on increasing resilience and reducing fragility, focused on strengthening public institutions to improve the state’s ability to mobilize resources, manage its economic affairs, deliver security and justice, and increase resilience to climate change and economic shocks, thereby contributing to social cohesion. Focusing squarely on Madagascar’s fragility drivers allowed the World Bank to leverage additional IDA resources through the Fragility, Conflict, and Violence Envelope’s Turn Around Allocation (TAA; box 2.3).

Figure 2.1. Madagascar’s Main Development Challenges to the World Bank Group Strategic Objectives, Fiscal Years 2012–21

Sources: World Bank 2011b, 2015b, 2017a.

Note: FY = fiscal year; PSD = private sector development.

Box 2.2. Influence of Political Economy Analysis for Risk Mitigation and Scenario Planning within the Country Partnership Framework

The Country Partnership Framework, “acknowledging that a scenario of renewed political unrest cannot be dismissed,” integrated analyses of the causes of weak governance and emphasized risk evaluation. In comparison with the Country Assistance Strategy—or even the Interim Strategy Note—the Country Partnership Framework more clearly stated the World Bank Group’s approach to risk mitigation: “adapt[ing] project design to take into account political economy and governance dynamics,” including by focusing on “implementation at the local level and includ[ing] systematic citizen engagement as a means to monitor results and manage risks” (World Bank 2017a).

The Country Partnership Framework also considered how objectives and activities might need to be restructured in the event of heightened political tensions or instability, for example by narrowing the program and scaling up mechanisms for citizen engagement and social accountability at the local level. The framework included three objectives pertaining to governance: decentralization, transparency and accountability, and fiscal space.

Source: World Bank 2017a.

The TAA’s requirement that a country makes meaningful progress transitioning out of fragility has empowered the Bank Group to confront Madagascar’s fragility drivers over the past five years, despite their overtly political nature. Objectives within the TAA framework included: (i) “[set] up other democratic institutions” (for example, the announcement of the 2018 parliamentary and presidential elections), (ii) “fight against rent capture and trafficking economy,” and (iii) “strengthen checks-and-balances (civil society, media).” Although the World Bank portfolio did not directly address all of these areas, it nevertheless supported them by tying financial incentives to completion of annual goals: failure to make significant progress toward milestones would lead to cancellation of undisbursed allocations from the TAA.

Box 2.3. International Development Association’s Turn Around Allocation

The International Development Association’s Turn Around Allocation (formerly the Turn Around Regime) provides additional support to countries undergoing complex transitions, beyond the amount determined through their performance-based allocation. It was designed to provide financial incentives to countries seeking to mitigate the drivers of fragility and take advantage of opportunities to build stability and resilience with the support of the World Bank.

Eligibility for the allocation requires, among other things, (i) development by the government of a strategy with concrete steps to accelerate its transition out of fragility and (ii) recalibration of the World Bank–supported strategy to bolster the government’s reform agenda. Continued eligibility is determined by the World Bank’s annual monitoring of the country’s progress relative to the corresponding milestones of the government strategy.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

The lack of engagement on the TAA with Malagasy civil society dampened the TAA’s impact on good governance. Although negotiated with other active development partners, failure to engage with civil society to ensure that the government’s proposed actions would actually address the country’s fragility drivers limited the overall efficacy of the TAA. In fact, some of the milestones supported indirectly or directly through the allocation—including, critically, the establishment of the High Court of Justice1—may have actually exacerbated the country’s political challenges: it has been argued that the court constitutes an additional source of impunity for politically exposed persons who are suspected of corruption and other misappropriations (Schatz 2019). Rather than support an additional entity, some members of civil society instead called for more consistent support to established players in the anticorruption system, that is, the Independent Anticorruption Bureau (the Bureau Indépendant Anti-Corruption), the anticorruption court (Pôles Anti-Corruption), and the Malagasy Financial Intelligence Unit (Transparency International—Initiative Madagascar 2021a).

Over time, Bank Group–supported strategies reflected a substantial shift in sensitivity to political economy and weak governance (World Bank 2021c). Table 2.1 visualizes the shift across the three strategies—filtered through the SCD—based on systematic assessment by the Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) in terms of three qualitative indicators. Central to this shift of monitoring, managing, and addressing Madagascar’s governance constraints has been the financial incentive stemming from the IDA’s Fragility, Conflict, and Violence Envelope and its TAA.

Table 2.1. Systematic Analysis of Political Constraints within Strategy Documents

|

Constraint |

Indicators |

CAS (2007–11) |

ISN (2012–13) |

SCD (2015) |

CPF (2017–21/2) |

|

Elite capture |

Identification or analysis of constraint as core driver impacting development? |

Somewhat |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Relevant outcomes? |

Noa |

No |

n.a. |

Yes |

|

|

Recommendations to manage or mitigate the risk? |

No |

Somewhat |

Somewhat |

Somewhat |

|

|

Overcentralized power |

Identification or analysis of constraint as core driver impacting development? |

Somewhat |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Relevant outcomes? |

Yes |

Somewhat |

n.a. |

Yes |

|

|

Recommendations to manage or mitigate the risk? |

No |

No |

Somewhat |

Yes |

|

|

Limited rule of law |

Identification or analysis of constraint as core driver impacting development? |

Somewhat |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Relevant outcomes? |

Yes |

No |

n.a. |

Yes |

|

|

Recommendations to manage or mitigate the risk? |

No |

No |

No |

Somewhat |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: CAS = Country Assistance Strategy; CPF = Country Partnership Framework; ISN = Interim Strategy Note; n.a. = not applicable; SCD = Systematic Country Diagnostic.a. Dropped.

The World Bank Group’s Increased Focus on Gender

The Bank Group–supported strategy in Madagascar was not adequately gender sensitive before the political crisis. The CAS only briefly mentioned gender with respect to reproductive and sexual health (including HIV/AIDS prevention and family planning). In contrast, the ISN focused on advancing women’s roles in the economy and identifying the main constraints that prevented women’s effective integration in society and business. It recognized (i) the role of women in Madagascar as catalytic to addressing development needs, (ii) the importance of equal remuneration in jobs, and (iii) the need to reduce discrimination in starting a business and in accessing productive inputs (that is, credit or land) and public services. Although this suggests progress in gender sensitivity in the strategy and design stages, results indicators only tracked improvements in mother and child health services, and HIV/AIDS prevention indicators were disaggregated by target groups such as commercial sex workers and youth by gender.

The Bank Group sought to revise its gender approach during the portfolio restructuring that followed the triggering of OP 7.30, but the scope of this revision was limited. The restructuring called for a review of the gender situation in projects to identify ways to refocus and enhance women’s role in the economy. It also highlighted the need to conduct both a poverty and inequality assessment, which would have a gender lens, and a gender assessment to identify the main gender bottlenecks and corrective measures that would enhance women’s role in society and business. In actuality, the Bank Group only ended up conducting one Poverty, Gender, and Inequality Assessment, in 2014, which described some dimensions of rural poverty in Madagascar with sex-disaggregated data, including on the specific barriers and extreme poverty rates faced by female-headed households. This was, in effect, a poverty assessment with sex-disaggregated data rather than a comprehensive gender assessment that would identify major gender bottlenecks and gender-sensitive measures to promote women’s participation in the economy, society, and business, as originally described in the ISN.

Although the SCD made efforts to identify key gender issues affecting development in Madagascar, gender was not mainstreamed in the analysis. The SCD identified four gender issues: gender gaps in labor participation, high fertility and population growth rates, disadvantages faced by female-headed households, and women and children’s vulnerability to indoor air pollution. It did not include analysis on other critical issues affecting women in Madagascar, such as gender-based violence (GBV) and unequal financial inclusion, access to land rights, and asset ownership. Furthermore, it did not adopt a gender lens in assessing sectoral constraints; gender was a separate issue rather than a cross-cutting issue that should be mainstreamed across all sectors.

The Bank Group’s understanding of how gender affected development in Madagascar improved throughout the CPF period, after additional analysis of gender gaps in agriculture and private sector development. Several CPF objective indicators tracked gender dimensions through disaggregation by sex. Analysis included gender-related barriers in (i) agriculture (including women’s lack of access and control over natural resources and assets, low productivity, and lack of social protection due to informality); (ii) land tenure (particularly information gaps in relation to land rights and registration); and (iii) the private sector (particularly barriers that affect women’s ability to cope with shocks, operate higher productivity enterprises, find jobs, and earn wages commensurate with those of men).

However, major gender issues related to rural development, such as links among gender and the environment, public sector governance, and GBV, began to be supported only in the past two years. In Madagascar, a third of women aged 15–49 years have experienced at least one form of GBV, about 1 in 4 women is a survivor of lifetime physical intimate partner abuse, and girls are often subjected to child marriage (almost 4 in 10 girls marry before the age of 18) and sexual exploitation (AfDB 2017; Diarietou 2020; MICS 2018). A 2021 review by Amnesty International found an alarming increase in GBV in Madagascar during the COVID-19 lockdown, from 1 in 3 women reporting violence to the organization in April 2019 to nearly 8 in 10 in April 2020 (Amnesty International 2021). Relevant World Bank support included a prior action in the human capital development policy financing supporting passage by the parliament of a law against GBV. Passed in January 2020, the law delineates new offences, such as spousal rape and sexual harassment, and defines new penal procedures (that is, mandatory reporting to end a culture of silence and acceptance of violence). The second human capital development policy financing supported implementation of said law through the development of multisectoral GBV coordination mechanisms and the expansion of GBV services and prevention programs.

- Although the establishment of the High Court of Justice was not mentioned within the Turn Around Allocation Framework, it was cited as one of the main achievements for that milestone (Demetriou 2019).