World Bank Support to Aging Countries

Chapter 3 | Engaging Countries on Population Aging

Highlights

The country engagement model is the key channel for analyzing the main constraints and opportunities for growth, prosperity, and poverty reduction at the country level, but it is not regularly and systematically used to assess the drivers and consequences of one of the most important phenomena affecting those: population aging.

The large body of aging-related analytical work produced by the World Bank has been used very selectively to inform its Systematic Country Diagnostics. The fiscal sustainability of pension and health systems is the issue most frequently discussed and is more likely to draw from existing analytical work. Quite welcome is the good attention in Systematic Country Diagnostics to labor market issues in relation to aging.

Country Partnership Frameworks are unlikely to discuss the challenges of population aging and its consequences, even in cases where the Systematic Country Diagnostic had a good focus on aging.

Country Partnership Frameworks that stand out are those that use demographic analysis to identify the challenges of population aging and propose policies for medium- and long-term solutions, for example those aimed at strengthening the human capital of the population.

Several factors inhibit the ability of the World Bank to engage more systematically with client countries. These factors include the lack of a natural counterpart in governments for such a cross-sectoral topic, the short time horizon of client countries, the absence of attention to population aging in World Bank corporate agendas (the Human Capital Project, future of work, inclusion, and gender strategy), and the insufficient use of partnerships to help advance the dialogue with the client.

The World Bank is increasingly aware that population aging is affecting the growth prospects and well-being of an increasing number of countries. But how effective is the World Bank in raising awareness of population aging and advancing it on the policy agenda of its client countries? This chapter focuses on World Bank engagement with governments on population aging and specifically on how the country engagement model has been used to inform the country’s understanding of the issue and elevate it as a priority for the policy maker. Although there are other ways in which the World Bank can trigger a policy discussion with its clients (some of which are discussed in the previous and following chapters), the country engagement model is the most regular and systematic channel through which to analyze, discuss, and prioritize issues that can affect growth and prosperity—demographic change being a pressing issue for many clients.

The evaluation found that the World Bank is not using the country engagement model to its fullest potential. The SCD reports about countries that are aging only occasionally discuss the impact that population aging can have on growth and shared prosperity, even in instances when they could rely on an existing body of relevant analytical work. The CPFs are therefore unlikely to recognize aging as an area of focus and to identify aging-related policy priorities. A few exceptions are noted. This is not to say that SCDs and CPFs are not raising issues that matter for aging—they are—but (i) they are not deliberately connecting them to population aging and hence are not using the powerful cross-sectoral SCD lens to integrate what is an eminently cross-sectoral issue; and (ii) they tend to focus on the immediate challenges—such as the fiscal sustainability of pension and health costs (essentially a constraint)—rather than on medium- and longer-term solutions; hence, they are not using the country engagement model as a platform to plan ahead. These two aspects—the cross-sectoral nature of population aging and the importance of anticipating challenges (preparedness)—are discussed in depth in the next chapter.

Country Engagement Model

The country engagement model is a key channel to bring population aging-related challenges to the attention of the policy maker. The SCD is the analytical underpinning of World Bank engagement with client countries.1 Its purpose is to identify the main constraints and opportunities for growth, prosperity, and poverty reduction to guide priorities for engagement. Since population aging affects productivity, consumption, savings, investments, and—ultimately—economic growth and prosperity, the SCD is the appropriate instrument for analyzing these impacts and identifying possible priorities for the CPF in a regular and systematic way.

Despite producing an increasingly rich body of analytical work, the World Bank has not used it systematically to inform its SCDs. Forty percent of SCDs in late- and postdividend countries do not have a demographic analysis that informs whether aging could negatively affect growth prospects and societal well-being. Although about half of the available SCDs for the universe of countries analyzed in this evaluation (24 out of 45)2 discuss aging issues, only 4 of them discuss the potential impacts of aging comprehensively—3 of them in Europe and Central Asia (Armenia, Bulgaria, Poland) and 1 in Latin America and the Caribbean (Uruguay).

SCDs that integrate aging well not only provide detailed information on the drivers but also discuss the potential challenges of population aging (box 3.1). The Albania and Armenia SCDs, for example, both identify low fertility and the strong outmigration of young (and disproportionately educated) people as drivers of aging. Both discuss issues that create special challenges for an aging society, such as the low participation of women in the labor market, the high level of informality, and the rapidly increasing outmigration (World Bank 2015b, 2017a). However, the Albania SCD does not discuss the ways in which these issues can affect future growth and prosperity. In contrast, the Armenia SCD uses a sensitivity analysis to project changes in gross domestic product in the context of halted population and different dependency ratios, depending on alternative levels of female labor force participation.

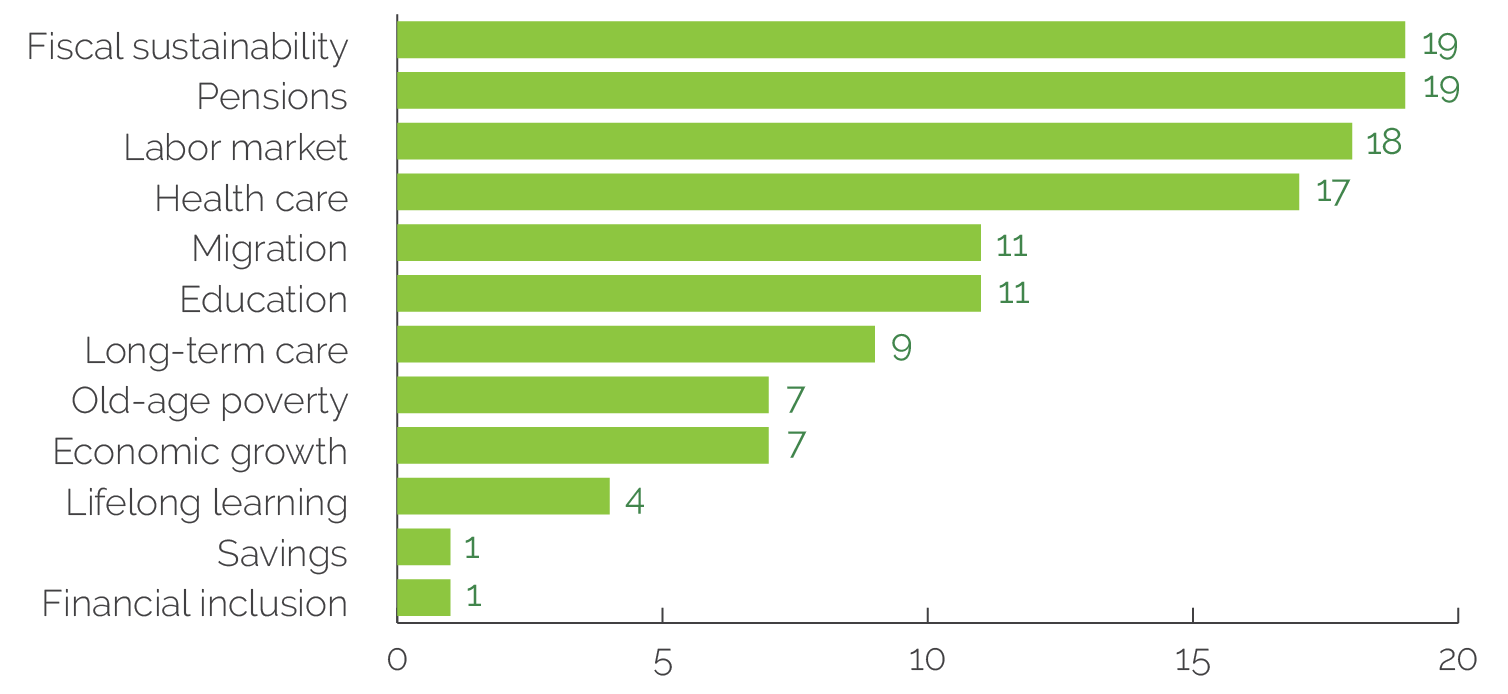

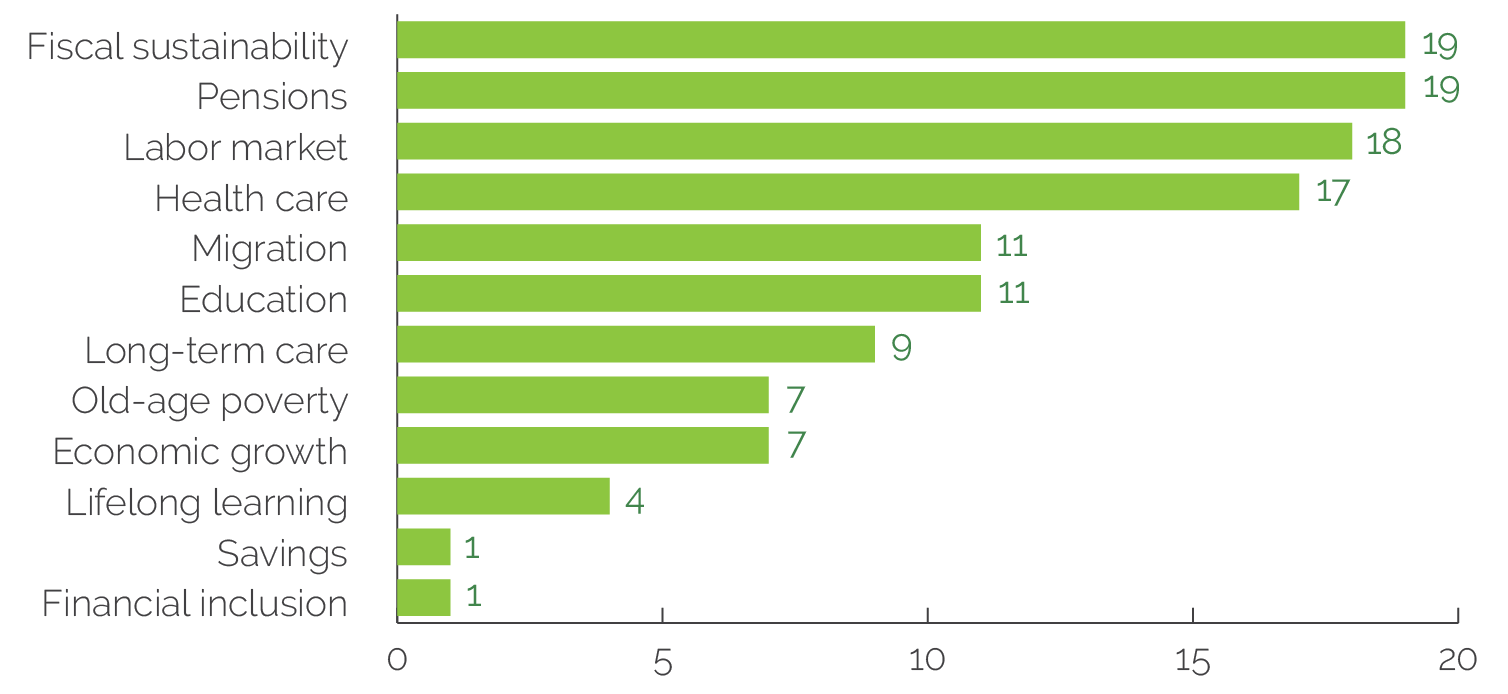

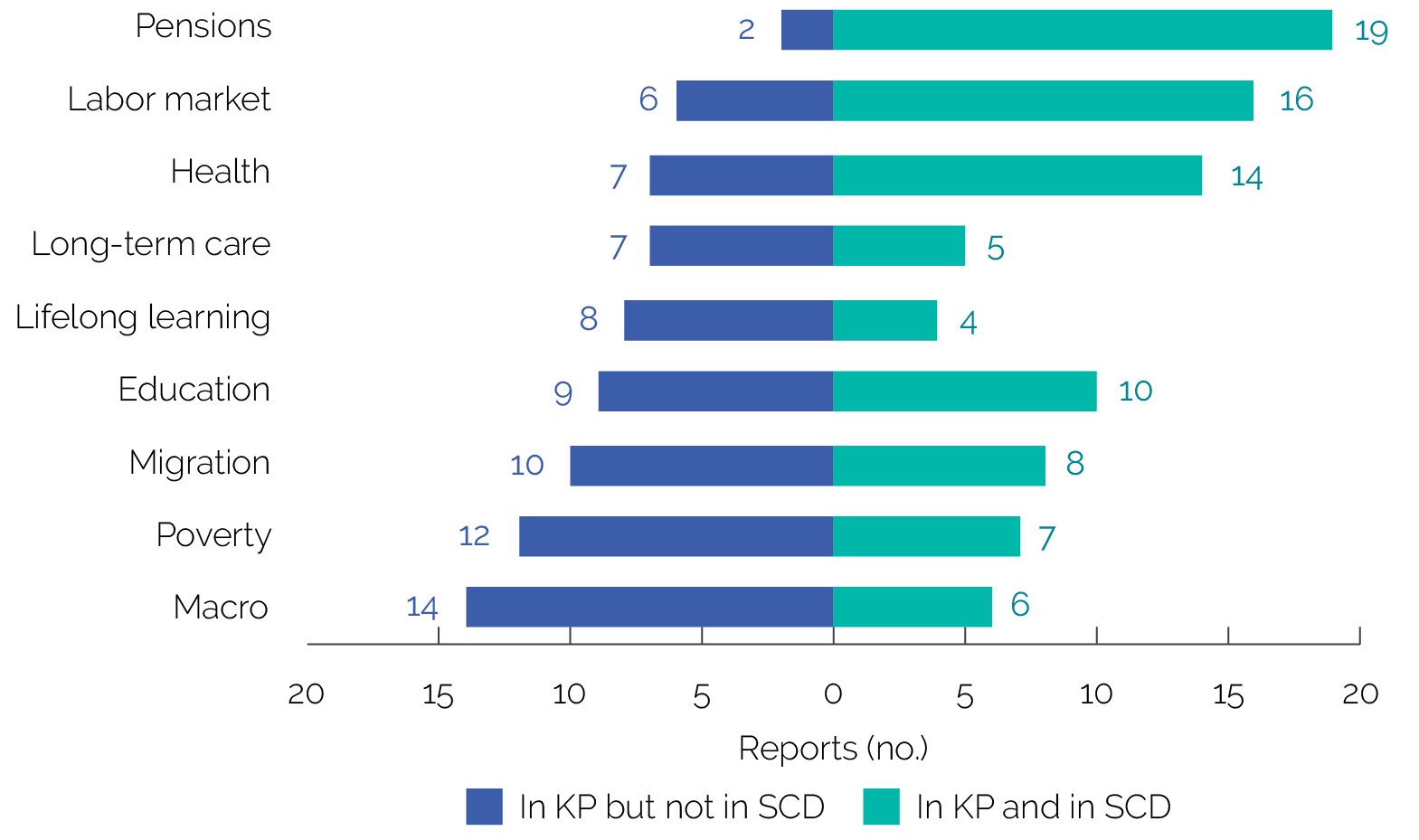

SCDs that discuss aging issues tend to focus on pensions and fiscal sustainability. Analysis of the fiscal sustainability pressures associated with the demands of an aging population is the most common aging issue discussed in SCDs (figure 3.1). This analysis highlights pressures driven by projected higher public expenses on health and pensions. In a few cases, the discussion includes potential negative impacts on the sustainability of the broader social assistance system (the Seychelles, Vietnam) or future demands for long-term care (Bulgaria, Thailand). Less common are SCDs presenting more granular analysis of how different segments of the population are affected now and will be in the future by population aging and hence by the current and future allocation of social expenditures.

Box 3.1. What Do Systematic Country Diagnostics That Integrate Aging Well Look Like?

The most salient features of Systematic Country Diagnostics that raise aging as a critical issue are the following: (i) they clearly identify the different drivers for aging; (ii) they use supporting data, or even original analysis, including projection modeling; and (iii) they present a comprehensive discussion of the implications of aging, including the links among affected areas. For example, they discuss how projected changes in labor force participation affect gross domestic product growth and education and skills needs; they analyze both how fiscally sustainable pension and health care systems are and their role in strengthening resilience and protecting from shocks; and they integrate the issues of increasing quality and availability of childcare and long-term care and supporting female labor force participation. Finally, (iv) they identify at least one policy priority related to aging.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

The focus on the fiscal sustainability of pension reforms is by far the most prevalent, dominating the discussion of pension coverage and adequacy. Of the 24 SCDs that include a discussion of aging, almost all (23) emphasize the potential negative impact that population aging will have on pension expenditure, but only a few include a thorough discussion of the coverage (11) and adequacy (6) of pensions, supported by empirical evidence. The Moldova SCD, for example, discusses the risk that population aging poses for the pension system’s sustainability, alongside a thorough analysis of the role of pension income in providing economic security to older people (World Bank 2016c). It also includes projections of replacement rates (ratio of pension to average wage) and pension coverage, and links very effectively the three elements—coverage, adequacy, and sustainability—to present options for reforms in the broader framework of improving social assistance programs. By contrast, the Belarus SCD raises the concern of the fiscal sustainability of the existing pay-as-you-go system without presenting data on pension coverage and adequacy (World Bank 2018a).

Figure 3.1. World Bank SCDs in Aging Countries Discussing Themes Relevant to Population Aging

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: n = 24 (45 countries have SCDs; of these, 24 discuss population aging). SCD = Systematic Country Diagnostic.

Labor market issues are an important area of focus in SCDs. Frequently mentioned is the importance of increasing workers’ productivity and women’s participation to counterbalance a shrinking labor force. Labor market analysis in the context of aging is often present in SCDs. SCDs of countries in Europe and Central Asia are more likely to flag that a potentially shrinking workforce due to population aging can negatively affect growth, present data and projections, and discuss policy options. The Armenia SCD, for example, highlights the need to look ahead and think of a new economic model, where barriers to work participation are removed to support female labor force participation, and investment in skills sustains workers’ productivity (World Bank 2017a). The Moldova SCD stresses the need to increase productivity and female labor force participation and to remove disincentives in the pension system for older workers to stay in formal employment (as opposed to moving to early retirement or inactivity, which would likely be a move to informality; World Bank 2016c). Although many SCDs concur that supporting female employment is critical (for example, by adopting family-friendly policies and strengthening care systems), they rarely tackle the issue of the employability and productivity of older workers. Often, investing in skills and boosting productivity is discussed in relation to young workers.3

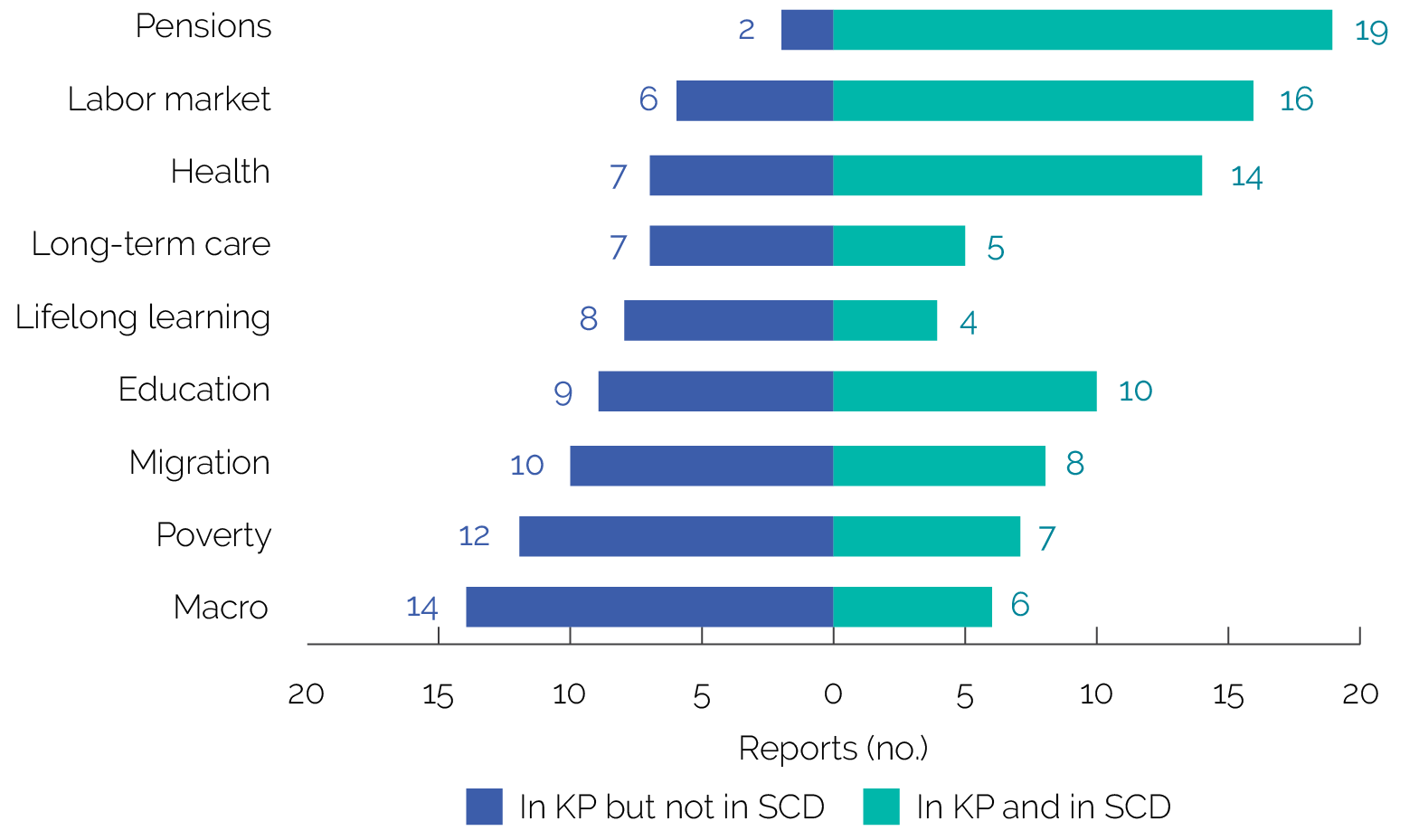

When SCDs do not focus on the challenges of population aging, or focus only on certain topics, it is not necessarily because relevant World Bank analysis does not exist. IEG observed a systematic bias toward using available empirical evidence to inform SCDs. Countries for which empirical analysis on pensions, the labor market, or health exists are much more likely to have SCDs discussing these issues; however, other topics, such as long-term care, lifelong learning, migration, or poverty are much less likely to be discussed in the SCD, even when World Bank–produced evidence exists that could inform that discussion (figure 3.2). Except in Bulgaria and Uruguay, SCDs in countries with an aging report are not more likely to have a comprehensive discussion of how population aging is or may be affecting their economy.

Figure 3.2. Using Existing Analysis to Inform SCDs

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: n = 24 (45 countries have SCDs; of these, 24 discuss population aging). KP = knowledge products; SCD = Systematic Country Diagnostic.

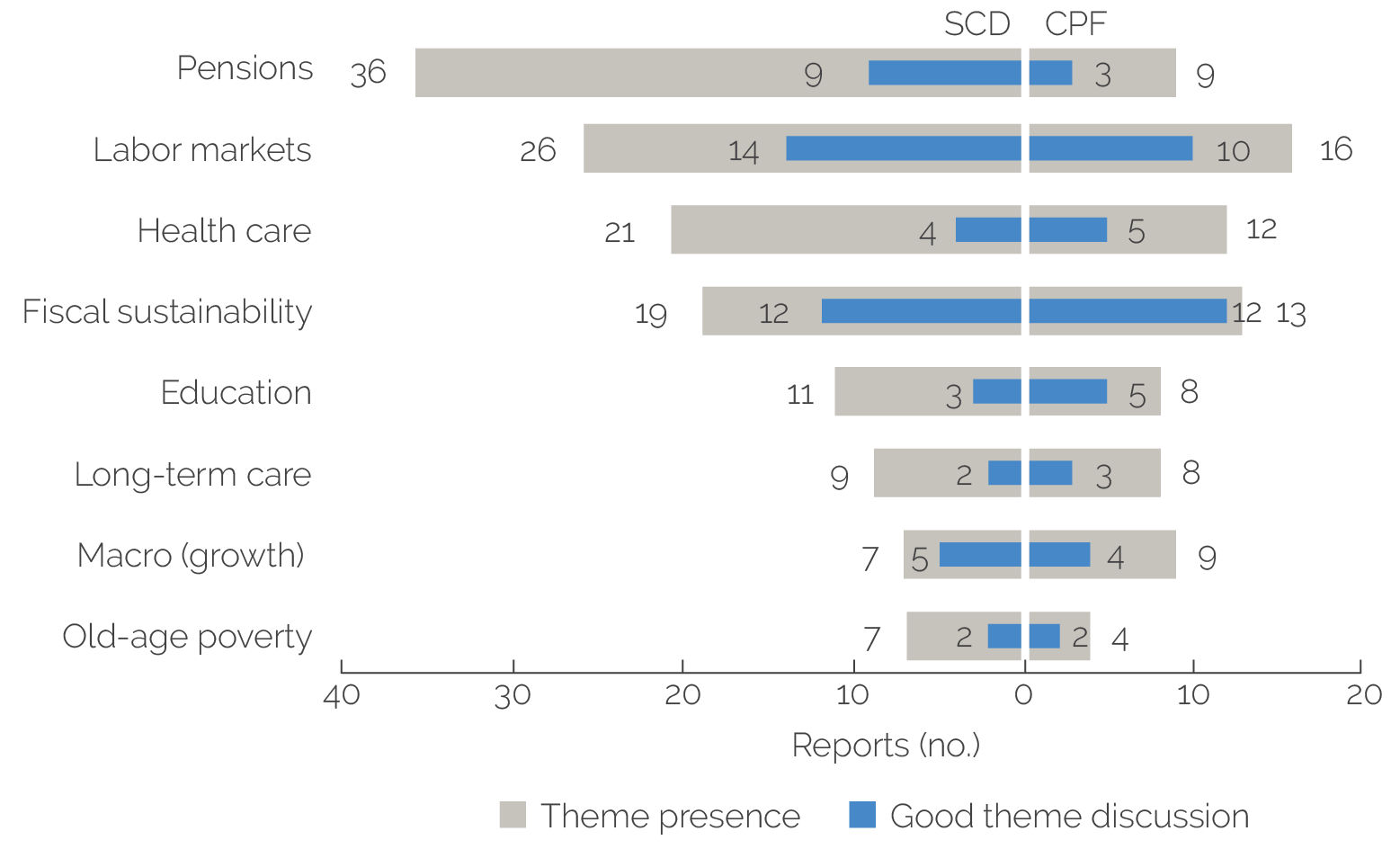

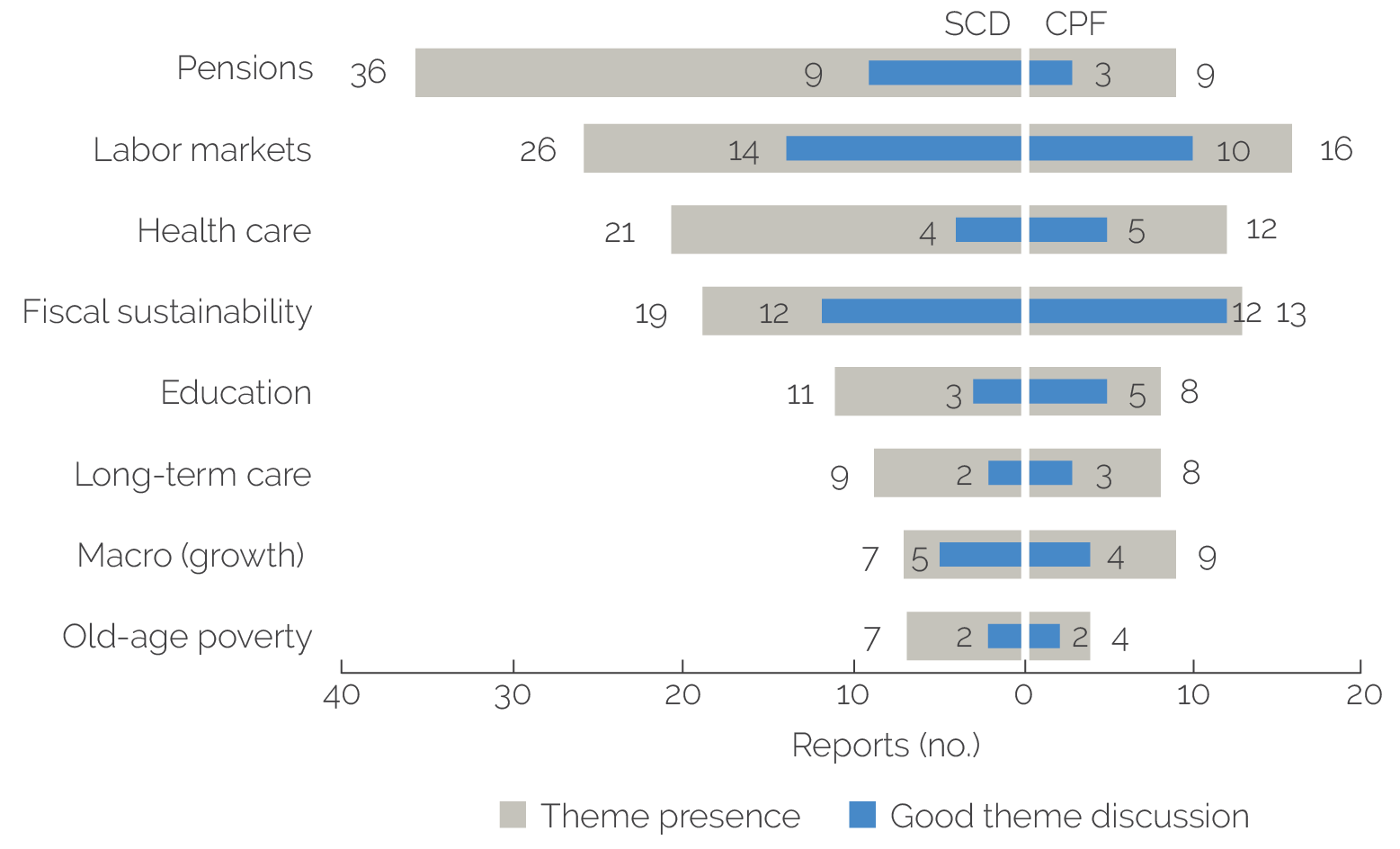

Like SCDs, CPFs seldom include a discussion of the challenges of population aging and its consequences. Sixteen CPFs out of the 36 available (42 percent) for post- and late-dividend countries do not mention aging at all. An additional 9 (25 percent) pay only cursory attention to it, with no supporting numbers, no reference period, no sense of evolution, and no explanation of the implications. Only 5 (14 percent) discuss aging-related issues with detailed descriptions of potential impacts, supporting data, analysis, and projections and place a strong emphasis on aging in the document.

A good discussion of aging in the SCD does not always carry over to the CPF (figure 3.3). Of the four SCDs that excel in identifying concrete policy priorities related to aging, only for Poland was this diagnostic translated into a CPF objective. For the other three countries (Armenia, Bulgaria, and Uruguay), the issue was raised in the CPF and the SCD analysis was used to inform or justify some of the other priorities. Many CPFs do not diagnose aging-related issues even when the SCDs (or other analytical work) do. Serbia is an example. The SCD links issues of labor force, pensions, health care, and education to aging (World Bank 2015i). It points to the need to increase the education level and inclusion of Roma people to counter the shrinking workforce. It also clearly articulates the issue of fiscal sustainability of pensions in relation to population aging. The CPF, however, does not reflect any of these issues (World Bank 2015h).

What distinguishes a CPF with a good treatment of population aging is its capacity to articulate a discussion of the challenges and policy options that can provide medium- and longer-term solutions based on data. It is not the number of themes or the focus on short-term constraints such as fiscal sustainability. The Croatia CPF identified four areas or themes connected to aging (labor force, growth, education, and long-term care) but neither presented supporting data nor included a discussion of the interrelationships among these themes (World Bank 2019a). The Uruguay CPF, however, highlighted just two themes in relation to aging—education, to strengthen the skill set, and labor force participation, to increase the productivity of its population—but the discussion was underpinned by good evidence for each (World Bank 2015k).

Figure 3.3. Aging-Related Themes in SCDs and CPFs

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: CPF = Country Partnership Framework; SCD = Systematic Country Diagnostic.

CPFs that discuss aging issues are often focused on fiscal sustainability issues associated with pension and health spending. Although necessary, addressing fiscal sustainability is not a solution to population aging; it consists of relaxing a short(er)-term constraint.

Gender issues related to aging are sometimes mentioned, mostly in relation to care responsibilities. This was the case in the Bulgaria, Poland, and Thailand CPFs. The Thailand CPF, for example, refers to the differential impacts of aging on older women, given their limited access to resources, including inheritance, and having to “shoulder a higher share of responsibilities of caring for grandchildren and older family members” (World Bank 2018e, 11).

CPFs that focused on the challenges of population aging identified policy priorities related to strengthening human capital as critical solutions. In the Costa Rica and Poland CPFs, changes in health systems are argued based on aging: “Population aging and a high prevalence of non-communicable diseases place a new set of challenges for health services in Poland, by increasing and altering the demand for care. This will require a different strategy and one that enables productive aging” (World Bank 2018c, 44). In Costa Rica “health services require adaptation to better tackle new demographic and epidemiological challenges to ensure quality and timeliness of service delivery” (World Bank 2015d, 29). In Bulgaria and Uruguay’s CPFs the logic for supporting education and skills rests on the rapidly aging population: “Against the backdrop of a rapidly aging and declining population, Bulgaria needs to equip its future cohorts of labor market entrants with the skills and competencies that would help the country make a significant leap in boosting employment and labor productivity” (World Bank 2016a, 36). “The education and skills agenda... are supporting productivity and competitiveness and preparing Uruguay for the aging of its population as demographic transition proceeds” (World Bank 2015k, 26).

CPFs that build on a more deliberate demographic analysis, usually provided by the SCD and other country diagnostics, can successfully provide a solid base for the formulation of policy priorities. Uruguay is a great example. The SCD and the country aging report were prepared almost simultaneously (the country report was published immediately after the SCD). This explains the SCD’s thorough analysis of the country aging-related challenges. The 2015 CPF, based on the analysis presented in the SCD and the country aging report, draws attention to the conflicting needs and expectations of younger and older people originating from a generous social protection system in the context of a rapidly aging population (World Bank 2015k). It indicates the priority of reforming the education system, investing in skills, and increasing workers’ productivity and country competitiveness to counter the potentially negative impact of a rapidly shrinking labor force. The strong demographic foundation of the CPF also allows for identifying the implications that population aging has for the social contract: “There is a need for concerted efforts to improve access to quality education and expand early childhood development programs. . . This reprioritization is of particular importance given that ongoing population aging will increase the relative proportion of elderly versus the working age population” (World Bank 2015k, 27).

The country engagement model is not the only channel for positioning aging on the policy agenda of client countries, but it is the most regular and suitable one. The analytical work—in the aging reports in particular—has been in several cases a good vehicle for establishing a fruitful policy discussion. In Uruguay, the aging report generated a positive momentum whereby the government produced a national strategy strongly centered on aging. In Chile, the aging report (launched during the IEG field visit in May 2019) was the result of a joint study program through which the government cofinanced the analysis. At the same time, the analytical work by itself is clearly not enough to move the needle. The very good aging reports of countries like Argentina and Brazil did not leave a mark on their SCDs and CPFs, which did not focus on the issue. The SCD-CPF model has the advantage of adopting a cross-sectoral analysis, bringing together teams from various Global Practices and being focused on challenges related to growth, poverty, and shared prosperity. It hence is the natural vehicle through which to discuss the implications of population aging in a regular and systematic fashion.

Constraints and Enabling Factors

What are the obstacles to a more regular and systematic engagement on aging issues between the World Bank and its client countries? This section analyzes elements that have been repeatedly raised with IEG—at both the global and country levels—and forms a consensus opinion.

Client Demand in a Country-Driven Model

All stakeholders interviewed for this evaluation (both government representatives and World Bank staff) agreed that there is a strong but often not well-articulated demand for World Bank support in relation to aging. There are several explanations. First, because population aging is a cross-sectoral issue there is no clear counterpart, in either government or the World Bank. In Chile, for instance, although the Office of the Presidency leads the agenda on aging, relevant programs are housed under the Ministry of Social Development, the Ministry of Health, and at the state level, with little coordination, strategic direction, or dedicated budget among these. Aging is not addressed across sectors in any of the countries IEG visited. Second, the minister of finance has typically a partial view of the aging agenda, that is, the immediate fiscal pressures arising from current and future pension liabilities. Third, governments are often shortsighted and unable or unwilling to plan long term. The governments’ time horizon corresponds to the electoral cycle, typically much shorter than the ideal time horizon to plan for population aging. This disconnect is often aggravated by the existence of severe fiscal constraints in aging countries. As a result, countries give limited attention to preparedness and underinvest in areas that require long-term investments, for example reskilling and lifelong learning or even long-term care.

Some governments may not see population aging as a government priority, even when the current trends suggest otherwise. In Jamaica, for example, despite the existence of aging strategies and plans, the government does not consider population aging as an urgent issue to be addressed. The strong outmigration is not perceived as a problem, given the large volume of remittances sent by migrants. A similar situation was observed in Bulgaria and Romania, despite pressures and incentives from the EU to invest in policies and programs to support active aging. Among the 12 early-dividend countries reviewed for this evaluation, only Argentina and Turkey recognize that aging may be a problem in the future.

The World Bank client-driven engagement model can be powerful in raising awareness of population aging challenges, but it has limitations. The World Bank issued seven policy notes on aging in the Russian Federation between 2014 and 2015, aiming to bring the issue to the attention of the policy makers. The comprehensive analytical work underpinning these policy notes was summarized in an overview report that was published and widely disseminated (World Bank 2015g). Yet it did not lead to additional lending or technical assistance. World Bank engagement is driven by country priorities, with plans and results set over a four- to six-year time frame, which may not be conducive to supporting longer-term efforts. Still, an in-depth demographic analysis in the SCD can show a country how population aging can affect its economy and help inform its formulation of policy priorities.

Corporate Priorities

Population aging is not included in four prominent corporate agendas that could catalyze country efforts. Population aging is surprisingly marginal in the Human Capital Project, future of work agenda, inclusion agenda, and gender strategy. The Human Capital Project aims to raise awareness and increase demand for interventions to build human capital and invest more in people’s education and health. The life cycle approach of the Human Capital Project is very conducive to extending the framework to the middle and later years of life and focusing the attention of governments on the economic costs of not preventing NCDs, in terms of (lost) productivity and (diminished) returns of human capital investments. The agenda was originally centered on the early years, but the World Bank is increasingly calling attention to how rising NCD levels threaten countries’ human capital because of productivity losses; it aims to include this issue in the Ministry of Finance agenda in client countries (World Bank 2019b).

The future of work agenda does not focus on the need to retool and retrain older workers. The World Development Report 2019: The Changing Nature of Work, for example, only tangentially mentions adult learning, but not in relation to aging countries, and mostly refers to out-of-work individuals (World Bank 2019h). Yet the review of SCDs has shown that labor market issues are among the most frequently analyzed in relation to population aging, as aging countries need to keep individuals active and productive for longer. Addressing skills mismatches, accelerating workforce reskilling, and promoting continuous learning could figure more prominently in the future of work agenda as policy priorities aimed at increasing the productivity of all workers, including older workers, in aging countries.

Aging is not an active part of the implementation of the gender strategy and inclusion agenda. Population aging has widespread implications for gender equality, as discussed in various parts of this evaluation and recognized by the World Bank Group Gender Strategy. IEG was unable, however, to discern a specific commitment by the Bank Group on addressing gender gaps in relation to aging. The issue is rarely even articulated. Also surprising is the lack of consideration of aging in the social inclusion agenda, given the important impacts of population aging on different groups. Further, the cultural impact of negative attitudes toward aging could jeopardize the efforts to make older people fully contributing members of society. The accessibility agenda led by the Sustainable Development Global Practice can have important overlaps with aging, but this work is not yet fully developed.

Collaboration with External Partners

Partnerships are not fully leveraged to raise awareness and move the aging agenda forward. Aging is becoming a priority in the work of several multilateral development banks and other international organizations. In the Latin America and the Caribbean Region, the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) has been actively investing in two lines of work related to aging—long-term care and the “silver economy”—and has recently launched the Aging Observatory, a centralized repository of data, publications, and references to “promote the design of effective policies to mitigate the impact of population aging.”4 The IADB also facilitates the intergovernmental dialogue in the Region on aging-related issues and is currently working on a position paper on aging, expected to be completed in 2021. In Europe and Central Asia, the EU requires accession countries to outline aging strategies and has promoted multiple initiatives to respond to population aging. Most recently, the European Commission has released a report on the drivers and impacts of demographic change (European Commission 2020), which will be followed by a green paper on aging.5 The OECD is producing relevant diagnostic work for both developed and developing countries and helps countries access EU funds for aging-related work. In the East Asia and Pacific Region, the Asian Development Bank has committed to help its member countries address the challenges of population aging as one of the key priorities in its 2030 strategy, including through sharing of experiences, best practices, and innovation (Asian Development Bank 2018). The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is increasingly calling attention to the topic in its publications.

Despite clear priority overlaps, IEG found little evidence of strategic collaboration or coordination on this topic. During country visits, IEG found many examples where the World Bank and other agencies were unaware of one another’s relevant material produced or initiatives promoted. This point was also made repeatedly during interviews with government officials and staff of multilateral development banks and other international organizations (notably the United Nations Development Programme, OECD, EU, International Labour Organization, and WHO, including its regional hubs). World Bank officials interviewed for this evaluation agree that there are few incentives to collaborate across institutions and that highly centralized and bureaucratic processes and procedures inhibit collaboration. The UN Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021–2030)6 calls for a concerted global effort to foster healthy aging and improve the lives of older people and their families and communities. It is yet to be seen whether the World Bank and other international organizations will support this effort.

In the Europe and Central Asia Region, the World Bank has provided technical assistance to EU accession countries to implement the EU active aging agenda, as a condition to benefiting from EU funds disbursement—with mixed results. In Bulgaria and Romania, for instance, the World Bank helped draft several relevant strategies to meet EU requirements. Interviews conducted for this evaluation indicate that in both countries these strategies are not being implemented as planned, and budgets have not been allocated. Implementation of the active aging agenda was not at the core of the EU reviews when assessing Bulgaria and Romania’s fulfillment with disbursing conditions, and governments had little incentive to implement the associated strategies. The World Bank was not included in any follow-up conversations after assisting with the preparation of the strategies, and EU officials were not able to monitor country progress in implementation. Although the client generally appreciated the World Bank’s analytical work and advice, it treated it opportunistically and did not disseminate it in the country. IEG findings suggest that, given the low commitment of countries to fulfill the active aging strategies promoted by the EU, there was little or no strategic coordination between the World Bank and the EU on how to best advance this agenda.

A few other examples of collaboration stand out. The World Bank collaborated with the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean to apply the NTA methodology in the Chile and Uruguay aging reports. There are examples of collaboration to produce knowledge products, such as the Pensions at a Glance: Latin America and the Caribbean report in 2014, with OECD and IADB, and the GMR itself, which was produced by the World Bank and the IMF (OECD, IADB, and World Bank 2014; World Bank and IMF 2016). Moreover, the World Bank has been supporting the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey, in collaboration with the US National Institutes of Health, the Chinese government, and Peking University. The only example of cofinancing is found in China, where the World Bank is cofinancing the Guizhou long-term care project with the Agence Française de Développement.

- The Bank Group approach to country engagement has four distinct components: (i) the Systematic Country Diagnostic, which is a diagnostic exercise conducted by the Bank Group in close consultation with national authorities, the private sector, and other stakeholders, as appropriate; (ii) the Country Partnership Framework (CPF), which builds selectively on the country’s development program and articulates a results-based engagement; (iii) the Performance and Learning Review, which is prepared every two years during the implementation of a CPF, or at midterm, and summarizes progress in implementing the CPF program; (iv) the Completion and Learning Review, which is prepared at the end of every CPF period to assess the CPF program performance using the results framework set out in the most recent Performance and Learning Review. In addition, the Country Engagement Note is used in very specific cases, where the Bank Group may not be able to prepare a CPF because uncertainty makes it impossible to commit to detailed objectives, develop a program, or engage at significant scale in the medium term. For more details on country engagement including policies, procedures, guidance, templates, learning, useful links, contacts, and other resources, see https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/country-strategies.

- Only 45 out of the 59 countries considered for this evaluation had a Systematic Country Diagnostic as of March 2019.

- For example, the Bulgaria Systematic Country Diagnostic acknowledges the debate on the impact of population aging on productivity but raises the policy issue about increasing productivity in relation to the younger generation: “[Because of the positive association between productivity and the share of younger workers] it will become increasingly important for Bulgaria to offer high quality primary and secondary education to most Bulgarians. This would enable younger workers to work in more technology-intensive sectors and facilitate life-learning. In order to achieve this, Bulgaria would need to reduce the high rate NEET youth [not in education, employment, or training] youth; improve the quality of education in some schools; and ensure that the Roma, who are an increasing share of the population, get better access to education” (World Bank 2015c, 46–47).

- For more information on the work of the Inter-American Development Bank on aging in Latin America and the Caribbean, see https://www.iadb.org/es/panorama/panorama-de-envejecimiento.

- A key goal of the report is to show the “need to embed demographic considerations across EU [European Union] policy”—a need that has been painfully demonstrated by the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic —and, through a statistical dashboard, provide countries with a “reliable basis for informed policy reflections and decisions” (European Commission 2020, 30). This report kick-starts the commission’s work in this area and will be followed by a green paper on aging, as demography is recognized as a cross-cutting issue that will help steer European recovery from the crisis.

- The proposal for the United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021–2030) was endorsed by World Health Organization member states at the 73rd World Health Assembly in August 2020. The proposal has four focus areas: (i) changing how we think, feel, and act toward age and aging; (ii) ensuring that communities foster the abilities of older people; (iii) delivering person-centered integrated care and primary health services responsive to older people; and (iv) providing access to long-term care for older people who need it (WHO 2020). More details about the proposal can be found at https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/decade-of-healthy-ageing/final-decade-proposal/decade-proposal-final-apr2020-en.pdf?sfvrsn=b4b75ebc_5.