World Bank Support to Aging Countries

Chapter 2 | World Bank Perspective on Population Aging

Highlights

The Global Monitoring Report 2015/2016 and several country and regional aging reports produced over the past decade have given the World Bank the framework to think about population aging (World Bank and IMF 2016). These reports have shown that population aging is a complex phenomenon that touches on virtually all sectors of the economy and can affect growth and inequality.

The number of reports focusing on aging-relevant issues has increased over time. This diagnostic work is often grounded in demographic analysis, even when it adopts a sectoral angle. Over time, this work, which until 10 years ago was mostly focused on pensions, has become more varied as more sectors have been covered.

The amount, type, and quality of work on aging is not clearly correlated with how old a country is or how pressing specific issues are. For example, the World Bank has produced less good evidence on the impacts of outmigration for countries with strong outmigration (one of the drivers of aging) than for countries where this is less of a problem. Similarly, countries with low female labor force participation or large gaps between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy are not more likely to have good analysis on these issues.

World Bank analytical reports do not systematically analyze distributional issues. Gender gaps, intergenerational inequalities, gaps between formal and informal workers, spatial inequalities, and socioeconomic disparities are discussed by a surprisingly small share of reports, and the attention to these issues has not increased over time.

The lack of appropriate data may explain the limitations of the distributional analysis. The data requirements to properly analyze the the multiple implications of population aging are substantial.

The World Bank has increasingly recognized population aging as a relevant issue for many of its client countries and developed diagnostic work to explore the evolution and the impact of this phenomenon and identify appropriate policy responses. This chapter assesses how far the World Bank’s diagnostic work aligns with country context and existing evidence, and how comprehensive it is. It also discusses the data requirements for the analysis of demographic trends and their implications. The findings presented answer evaluation questions 1a and 1b and part of question 2 (see box A.1 in appendix A).

IEG found that the World Bank work on population aging has evolved over the past 15–20 years and that this evolution had two main merits: it led the World Bank to (i) widen the analysis of potential impacts of population aging to more sectors and topics; and (ii) more frequently use a medium- and long-term perspective to inform its support to aging countries.

Two issues in particular deserve more attention: (i) there is some disconnect between country needs—measured by the demographic challenges faced by the country, according to the data—and the issues explored in the World Bank’s analytical work; and (ii) the impacts of demographic change for different subgroups of the population are not systematically analyzed.

Evolution of the World Bank’s Diagnostic Work on Aging

The World Bank’s understanding of population aging as an issue relevant for development has gone through several phases, from a narrow focus on the sustainability of pension systems to a broader perspective encompassing the whole economy. The first World Bank report on aging was Averting the Old Age Crisis: Policies to Protect the Old and Promote Growth (World Bank 1994).1 This report focused on old-age security programs—and related policy options for reform—and called for reforming old-age financial security systems to meet the goal of protecting the old at the same time as avoiding negative impacts on growth.2 More than a decade later, From Red to Gray: The “Third Transition” of Aging Populations in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union was the first report to adopt a broad, cross-sectoral lens to analyze the interrelated impacts of population aging on productivity, savings and financial markets, pension and health systems, social security budgets, long-term care needs, and education and to define a vision for the World Bank’s support to countries in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union (World Bank 2007b).

The approach proposed in From Red to Gray is novel with respect to previous analytical work. Older reports had zoomed in on very specific issues, mostly poverty in old age and pension reforms (Aiyer 1997; Deaton and Paxson 1991; Holzmann 1999; Holzmann and Hinz 2005; World Bank 1994; World Bank 2005), especially in transition economies (Fox 1994; Kudat and Youssef 1999). In From Red to Gray, the World Bank introduced the concept of aging as a structural and comprehensive phenomenon.3

Over the past 10 years, several country and regional aging reports have used demographic analysis to study the drivers and impacts of population aging and identify possible policy responses. From Red to Gray paved the way for other aging reports (at the Region and country levels) and the GMR (World Bank and IMF 2016), which also discuss population aging as a systemic change with economywide implications to be analyzed and addressed. The regional reports published over the past few years were Population Aging: Is Latin America Ready? (World Bank 2011c), Golden Aging: Aging in East Asia and Pacific (Bussolo, Koettl, and Sinnott 2015), and Live Long and Prosper: Aging in East Asia and Pacific (World Bank 2016b). A second report on the Latin America and the Caribbean Region was released in 2020 (Rofman and Apella 2020). Country-focused aging reports have been issued for six countries—in chronological order, Brazil, Bulgaria, Argentina, Latvia, Uruguay, and Chile (Apella et al. 2019; Gragnolati et al. 2015; Rofman, Amarante, and Apella 2016; World Bank 2011b; World Bank 2013; World Bank 2015a). The GMR and the aging reports represent the World Bank’s reference framework to understand the aging challenges of its client countries—and how policies can help turn those challenges into opportunities—before the transition becomes too advanced.4

The GMR and the aging reports find that the impacts of population aging on growth and individual well-being vary by country and by population subgroup within countries. The GMR and many recent knowledge products highlight that population aging may weaken future growth but not necessarily, if the right policies are adopted, as other studies have shown (Bloom, Canning, and Fink 2010; Onder and Pestieau 2014). Several reports show, for example, that countries can reduce or even reverse the negative impact of an aging society on growth and well-being by maintaining a favorable labor force dependency ratio—that is, people living longer in good health and being active and more productive for longer in the labor force—thanks to investments in health, education, skills, and lifelong learning. They also discuss the regional and subregional differences across countries and the different implications that population aging has for different groups of the population within individual countries. The Golden Aging report (Bussolo, Koettl, and Sinnott 2015), for example, shows how the chances of living longer and healthier lives differ depending on education, income, and sex. Although the report highlights the fact that aging may bring opportunities, it also stresses that these opportunities may not be available to everyone. Earnings and savings gaps between skilled and unskilled individuals tend to increase with age; thus, the increasingly larger older population may be divided into two categories: a poorer and less-educated group that suffers from bad health, relatively shorter life expectancy and lower savings, and another group that is still active, has more assets, and benefits from increased healthy longevity.

The analysis presented by the GMR and the aging reports highlights the dynamic character of aging and the need for client countries to anticipate the challenges ahead. The GMR identifies aging countries using a dynamic definition, which combines changes in fertility and the working-age population. This definition classifies as aging countries those that may still be young (based on the current share of older people in the population) but that are expected to grow older soon. This dynamic definition provides the World Bank with a strong business case to advise its clients to maximize the benefits of the first demographic dividend (when the share of the working-age population reaches its peak) and create the conditions for a second demographic dividend (when the share of the working-age population decreases, but the economy can take advantage of the increased savings, investments, and productivity of the previous phase).5 As fertility and mortality rates decrease, countries move across subsequent demographic transition stages, and their window of opportunity to adapt to population aging shrinks.

One area that remains less prominent in the World Bank’s aging diagnostic work is the reference to social norms, perceptions about aging, and the cultural change that needs to happen for a society to be able to embrace an aging population. Ageism—or the negative stereotyping of older adults, who are assumed to have mental or physical impairments due to their age—has been found to have negative repercussions at the individual and societal level. Negative stereotyping can, for example, affect individuals’ memory and sense of worthlessness, cause depression, and even shorten their lives (Han and Kim 2010; Levy et al. 2002). These negative effects on health are pervasive across countries (Chang et al. 2020). A recent study calculates that ageism has substantial costs to society in terms of higher health costs (Levy et al. 2020). Considering aging as a social problem can also be an impediment to reorganizing societies to address the socioeconomic impacts of population aging; for example, it can translate into age discrimination in employment and discourage older people from remaining in the labor force.6 Although some reports emphasize the critical policy goal of enabling a more active population (for example, Bussolo, Koettl, and Sinnott 2015), none of the World Bank reports discuss in depth the importance of and the options for changing norms to avoid reinforcing negative perceptions and creating instead a positive attitude toward aging.7

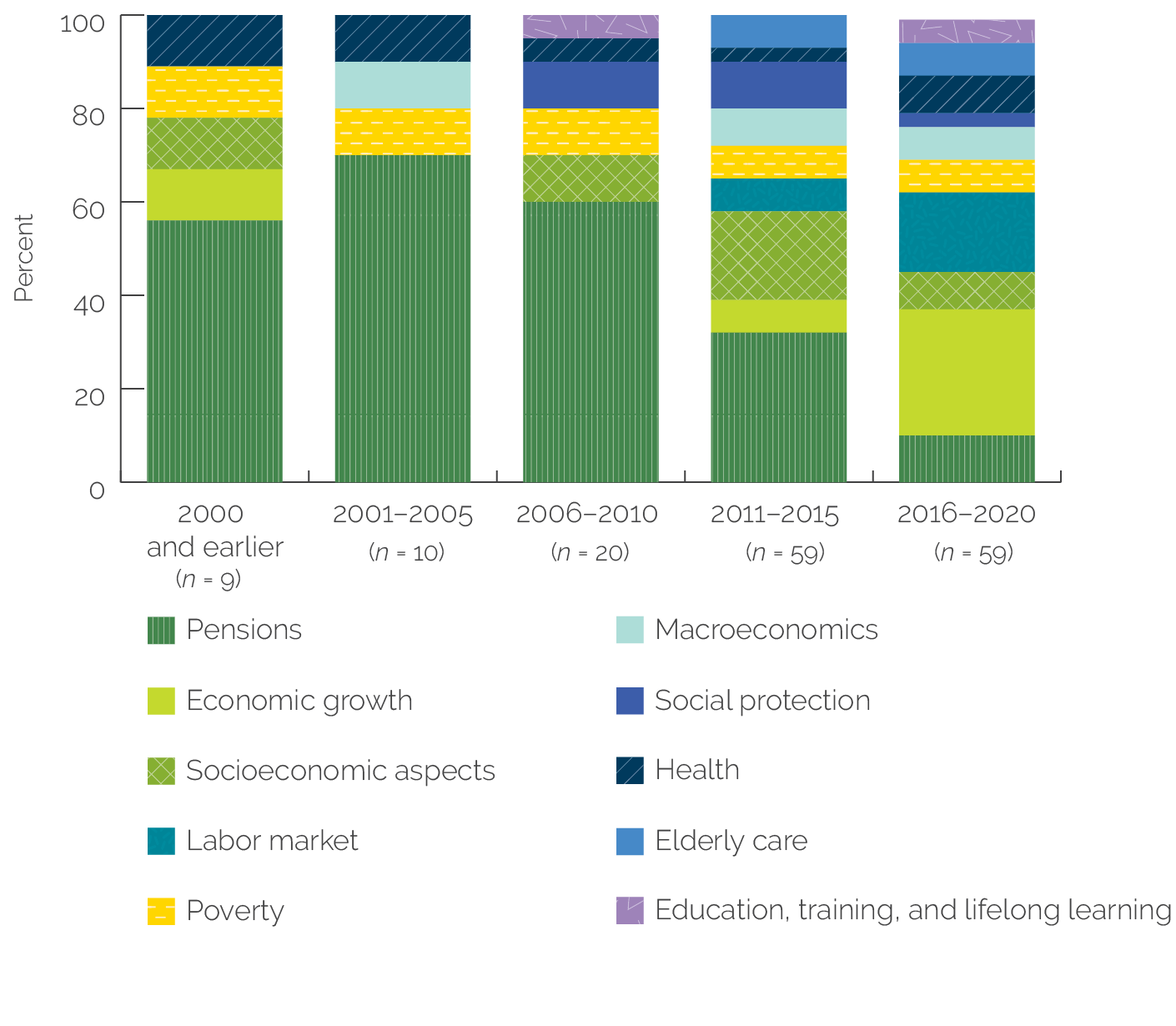

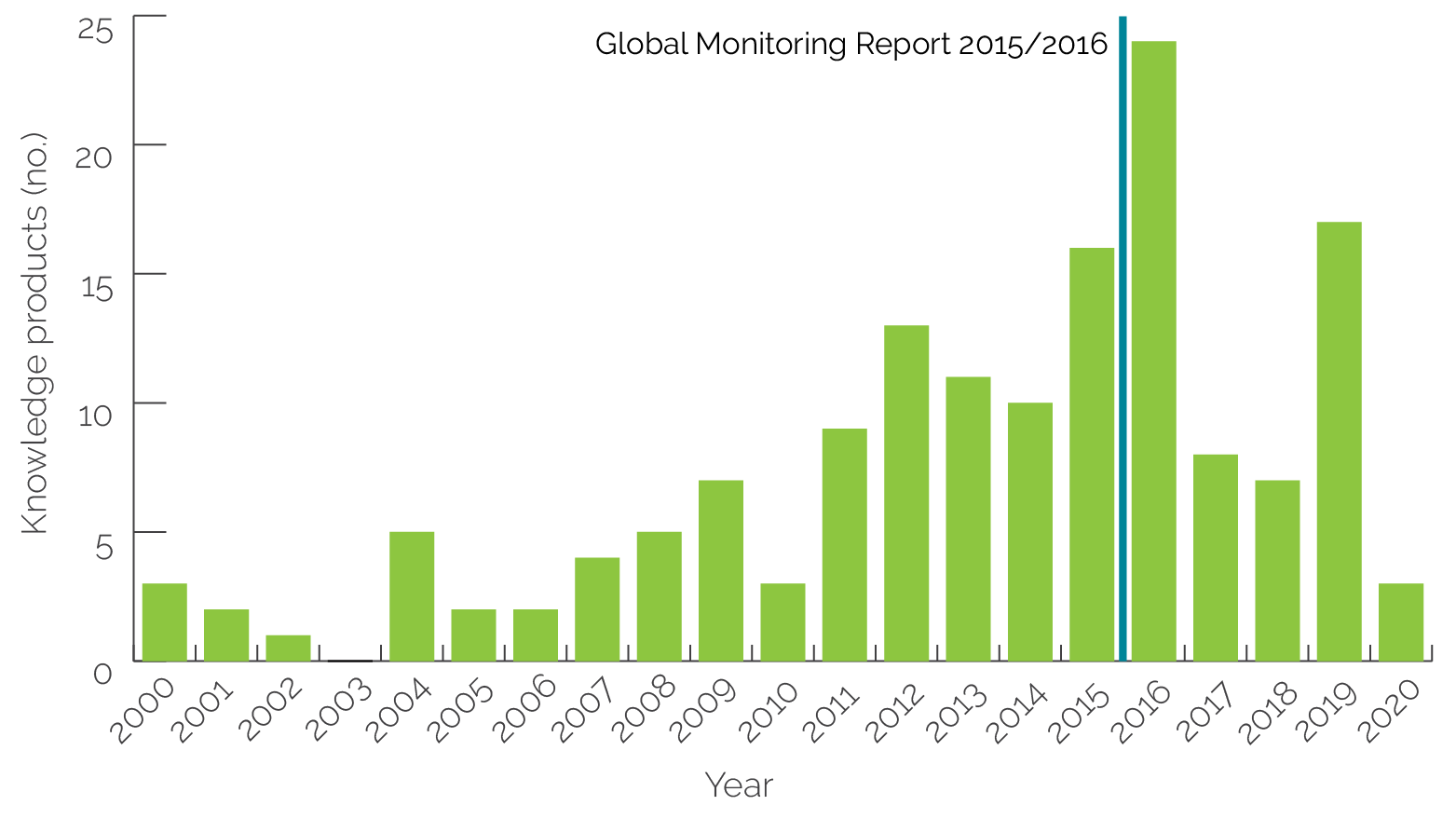

An increasing number of the World Bank’s analytical products focus on the economic and social implications of population aging. Using the framework of figure 1.1, IEG has identified a set of core knowledge products that inform the analysis of population aging and its implications for the countries covered by the evaluation (the selection of these products was validated by the CMUs; see appendix D for the selection criteria). A few of these 157 reports (the country and regional aging reports) are comprehensive and analyze the cross-sectoral relationships of aging; most of them zoom in on one or a few specific topics. This core set of knowledge products does not include SCDs, which are analyzed separately given their strategic function of informing country engagement (see chapter 3). The number of reports has increased over time, particularly during the past decade, and especially around the time of the GMR, with a new spike in 2019 (figure 2.1). Not surprisingly, almost half of these reports refer to the Europe and Central Asia Region (73), followed by East Asia and Pacific (26) and Latin America and the Caribbean (21). Younger Regions have a handful of reports: Sub-Saharan Africa (4), Middle East and North Africa (4), and South Asia (8). Twenty-one are global reports.8

The common characteristic of these reports is reliance on an analysis of demographic trends, by either developing an original one or referring to an already existing one. Two-thirds of the knowledge reports include some demographic diagnostic, either as their main focus or as a starting point to develop a sector- or topic-specific analysis of the impacts or implications of population aging. They may investigate the drivers and present projections of the speed of population aging, sometimes using rich and original data sets, and show how these trends are likely to affect economic growth, labor productivity, or health needs. A paper for Poland, for instance, uses a variety of sources, including original qualitative data on the demand and supply of care services for older adults, to produce a detailed diagnosis of long-term care needs based on longevity patterns by region and gender (World Bank 2015f). Those reports that do not include a demographic analysis focus nonetheless on topics clearly related to population aging, such as reforming pensions or adapting social security and health systems to an increasingly older population. For example, a recent report analyzes the performance of the Ecuadorian pension system and produces simulations of coverage, total expenditures, and financial results using administrative data and the United Nations Development Programme population projections (Apella 2019).

The work on pensions, which was the predominant subject for a long time, is no longer the lion’s share of the World Bank’s work on aging. Over the whole period, most knowledge products focused on pensions, a long-standing tradition of the World Bank’s work. When a single theme (main topic) is assigned to each report, almost one-third of the reports reviewed are classified under “pensions” (figure 2.2). However, the relative importance of pension reports has greatly diminished over time, as a much larger variety of topics has been added to the pool (figure 2.3).

Few reports focus specifically on health, although health is frequently discussed in reports covering multiple topics. This is quite surprising, considering that (i) healthy longevity is essential to increasing human capital and productivity and diminishing the negative impacts of population aging; and (ii) along with pensions, health is one of the most long-standing areas of the World Bank’s support to countries. Yet health as a specific concern of aging countries has not received widespread attention at the level of diagnostic work.

Figure 2.1. World Bank Aging Knowledge Products by Fiscal Year of Publication

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The vertical bar represents the date of publication of the Global Monitoring Report.

Figure 2.2. Content of World Bank Knowledge Products

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Figure 2.3. Evolution of Topics Discussed in World Bank Core Knowledge Products

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Several reports use new tools and methodologies that facilitate the analysis of multiple implications of population aging. The Latvia aging report (World Bank 2015a), for example, uses the Active Aging Index to explore inequalities in employment and health outcomes by sex, educational attainment, and geographical region.9 Several reports, mostly in the Latin America and the Caribbean Region but also in the South Asia Region, use the National Transfer Accounts (NTA) methodology to tease out the links between individual and aggregate income, consumption, and savings over the life cycle and explore the interconnections among population aging, labor force participation, productivity, and asset accumulation and decumulation (and investments) (Apella et al. 2019; Gragnolati et al. 2015; Rofman, Amarante, and Apella 2016; Rofman and Apella 2020; World Bank 2012b).

The NTA methodology allows the World Bank to highlight the connections among several sectors of the economy and introduces a more flexible definition of aging. The NTA application shows the links between earnings and consumption over the life cycle—that is, the relationships among participation in employment, productivity, and spending capacity. Using scenario analysis, this methodology allows for analyzing the evolution of private and public expenditures (including public and private spending on health care and, especially, of public spending on pensions and social protection) and highlights the positive contribution of female labor force participation and education to economic activity, productivity, and gross domestic product growth in a context of population aging. The NTA methodology de facto introduces a different way to think about dependency that is not linked to a predetermined age (such as 65) but is based on the ratio between earnings and consumption (essentially, the dependency rate in this framework is the ratio of people weighted by age-specific earnings and age-specific labor force participation to people weighted by age-specific consumption).

The World Bank analytical work has helped countries recognize that population aging is a challenge that requires swift action, in some cases generating concrete responses by governments. Uruguay is one of the oldest countries in Latin America; still, the 2016 aging report generated a new sense of urgency and a need to act to address the many challenges of population aging (Rofman, Amarante, and Apella 2016). Government officials stated that the preparation of the country aging report was fundamental to structuring the policy discussion about aging. The 2050 country development strategy draws from several World Bank reports, including the diagnostic work of the aging report. The strategy identifies demographic change as a main force requiring adequate responses concerning the labor market, social protection, demand for health services, and long-term care (Uruguay 2019). The strategy was prepared by a unit within the Budget and Planning Office, which was created as the World Bank engaged in regular dialogue with the government for the preparation of the country aging report.

In China, the high-quality diagnostic work and policy advice provided by the World Bank paved the way to the approval of the first two loans for piloting the development of long-term care systems. In 2011, the World Bank responded to the Chinese government’s request and conducted analytical work to support China in its effort to build a comprehensive policy and institutional framework for long-term care. The diagnostic work was instrumental in the development and subsequent approval of the first two inaugural projects entirely focused on long-term care in World Bank history: Anhui (approved in June 2018) and Guizhou, in cooperation with Agence Française de Développement (approved in March 2019). Both projects support the government’s goal to establish a three-tiered aged-care system, with a stronger emphasis on home- and community-based care, and to foster the development of an efficient market for long-term care provision. Project activities aim at building capacity to strengthen the government stewardship role, including the accreditation of community-based care, homecare, and nursing-care providers and setting standards for the quality of services they provide. The World Bank support also helped define the basic package of services, the eligibility criteria, and priority access for publicly subsidized services.

The long-standing World Bank Pension Reform Options Simulation Toolkit (PROST) model has a well-established reputation with governments and international partners; it supports pension reforms. The PROST model, refined over the past three decades, has been used to simulate the behavior of pension systems, assess their financial sustainability under different demographic and economic assumptions, and address questions related to the coverage and adequacy of pensions (World Bank 2010). There are many examples of applications of the model in the reports analyzed by IEG. These include analysis of pension reforms as part of either country-specific pension policy reports or broader reports such as public expenditure reviews in Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Ecuador, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Moldova, Mongolia, Montenegro, and Ukraine. Most of this work is highly specialized and focuses on fiscal sustainability issues, a critical complement to other aging studies. PROST was described as one of the World Bank’s successes by several people interviewed by IEG for this evaluation. For example, the European Commission appreciates that several European Union (EU) countries (including Romania, one of the case study countries for this evaluation) can use PROST to forecast the impact of the change in population structure on public finances, as the European Commission would otherwise be unable to produce them directly because the model needs to be customized to the country context.

Insufficient Connection with the Country Aging Context

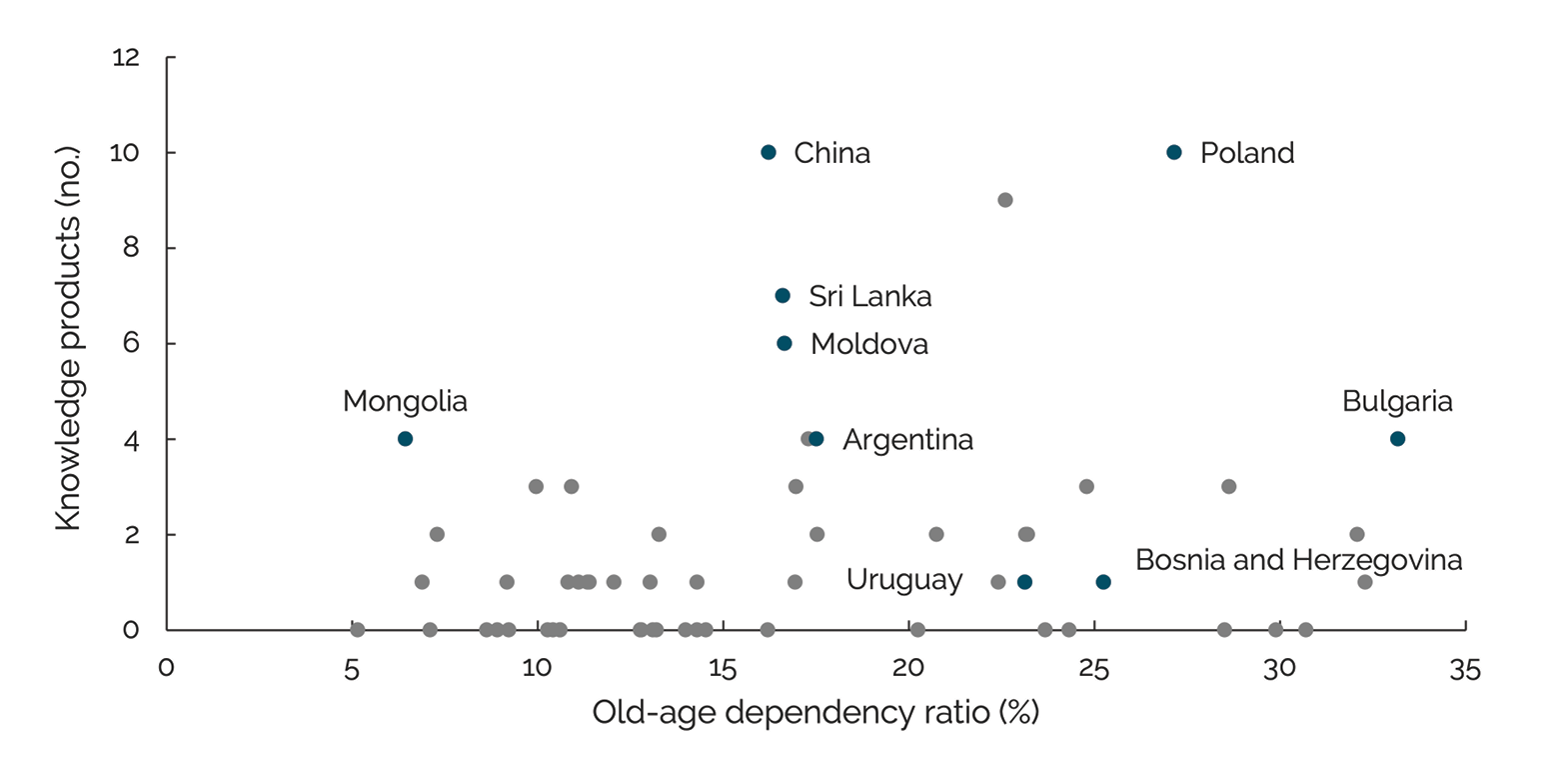

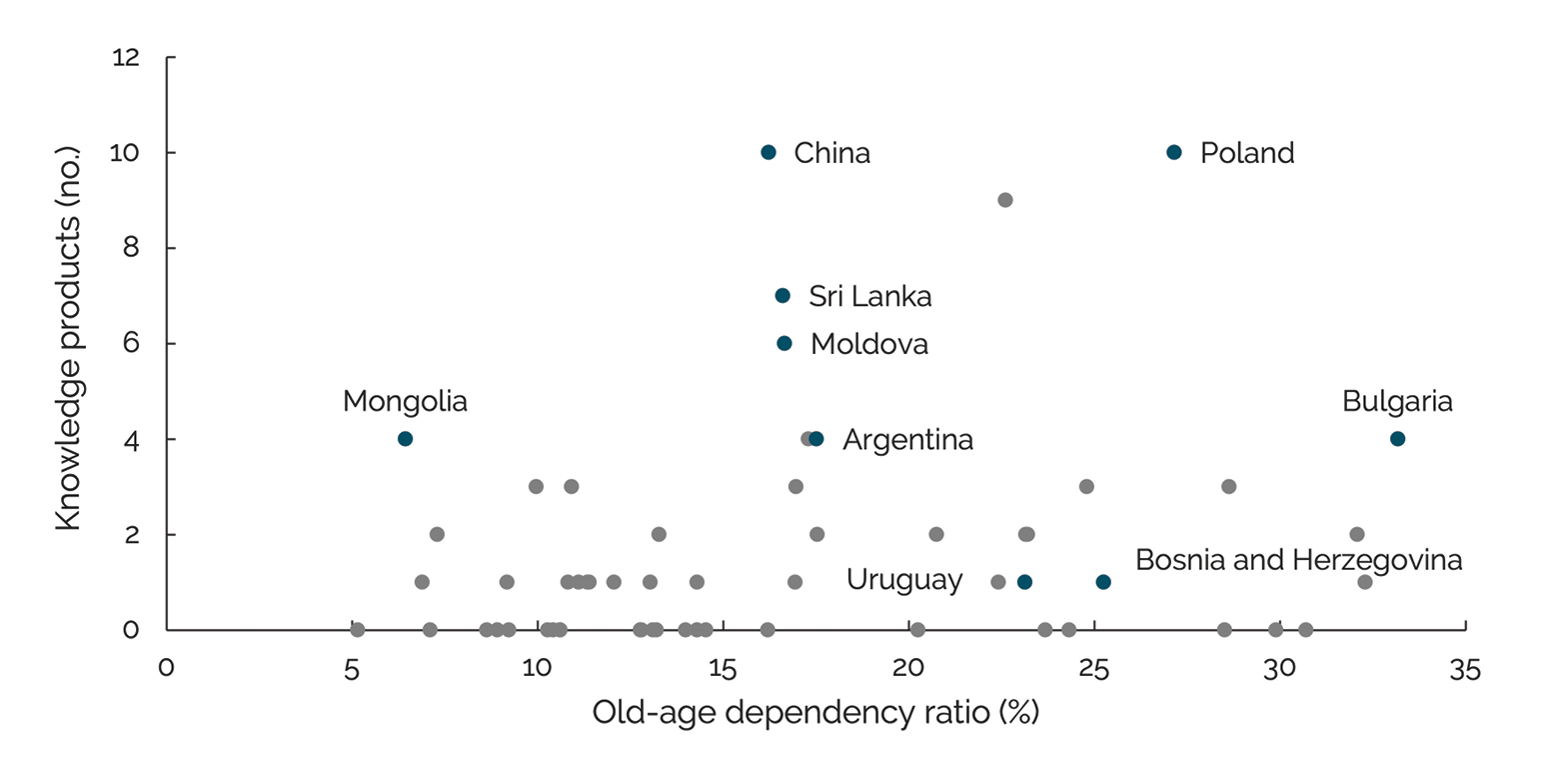

The World Bank’s production of diagnostic work does not show a clear correlation with the country aging context, measured by select aggregate statistics. IEG observes that there is little association between the number of reports on aging-related issues and the country’s stage of population aging.10 No correlation is observed between the number of reports and how advanced a country is in the demographic transition (figure 2.4).11 China has a similar number of reports (high) as Poland, which can possibly be explained by both the rapid pace at which the country is aging and the existence of operations in new areas (like long-term care). However, a relatively young country like Mongolia has the same number of reports as the oldest country: Bulgaria. And Moldova and Sri Lanka stand out as countries with many more reports than countries that are older, such as Bosnia and Herzegovina or Uruguay. Similarly, the oldest or more rapidly aging countries are not the ones with country aging reports: Argentina, for example, has an aging report but is still not technically an aging country, whereas many countries that are well advanced in the aging process have never had an aging report.

Figure 2.4. World Bank Knowledge Products by Country and Stage in the Aging Process

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Old-age dependency ratio is defined as the ratio of older dependents (people older than 64) to the working-age population (people ages 15–64).

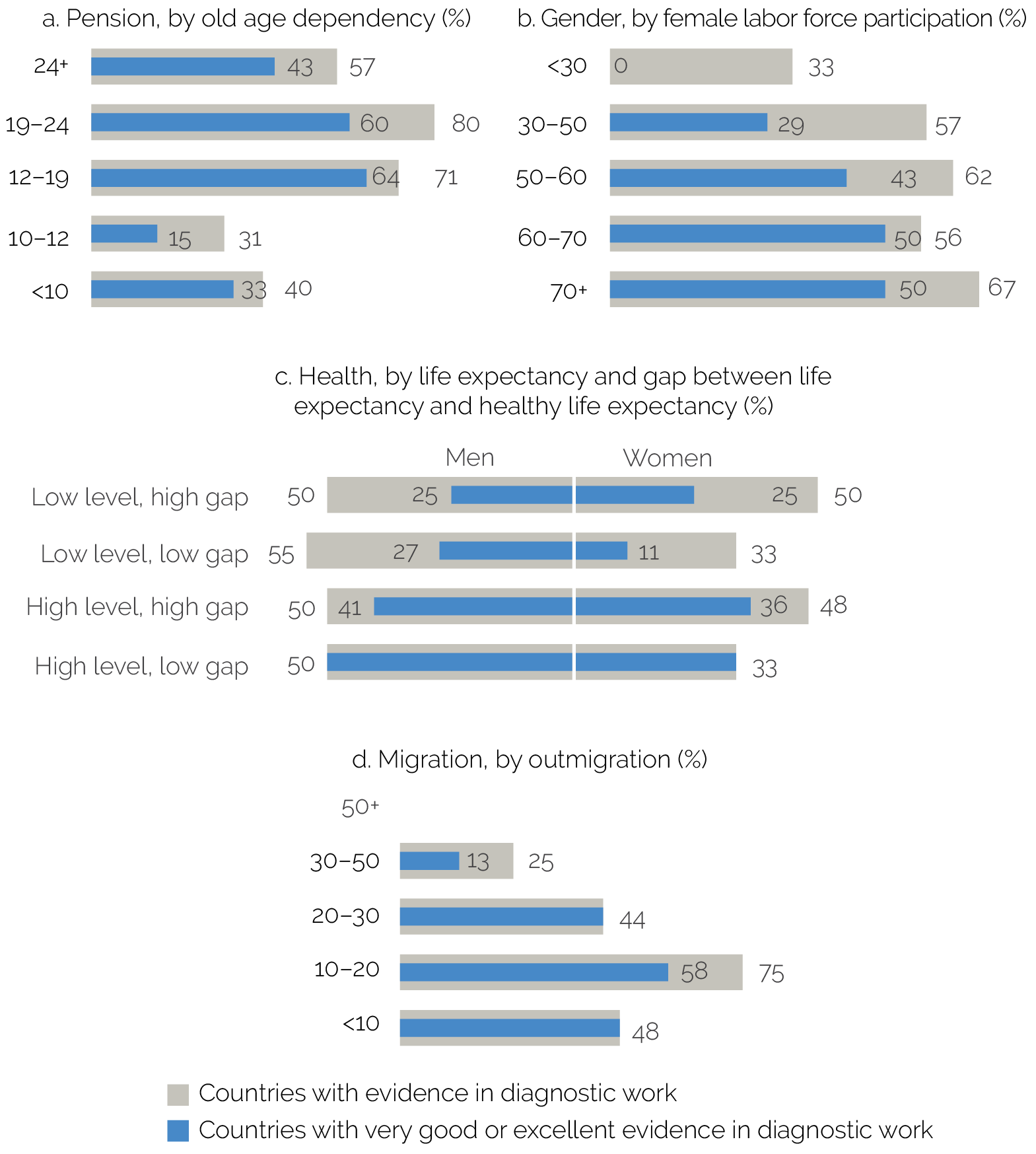

The World Bank has been more systematic in providing country-level diagnostics on some drivers of population aging (and related implications) than others. The correlation between the type of challenges faced by the country and the type of diagnostic provided by the World Bank is weak. IEG has looked at the existence, type, and quality of evidence at the country level and how it matches with specific country challenges.12 Although all countries are aging, the country-specific drivers and the ways in which they play out can differ substantially, as do the issues, challenges, and potential policy responses. IEG has used aggregate data to classify countries based on some of the specific challenges they face—a high share of older people in the overall population, low female labor force participation, strong outmigration, and large gaps between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy—and paired these data with the type and quality of existing evidence (figure 2.5).

IEG observed that the countries for which specific age-related challenges are at a high level of urgency are just as likely as countries at a low level of urgency to have benefited from World Bank diagnostic work on aging. In other words, coverage, in terms of existing evidence on a specific topic, is not correlated with country needs based on demographics. Furthermore, the quality of diagnostic work is not correlated with level of urgency. We may have expected to see higher quality work on aging for countries with higher needs based on their demographic profile, but this was not the case. Not all the oldest countries have had country-specific diagnostics on pensions carried out over the past 20 years (figure 2.5, panel a).

Figure 2.5. Correspondence between the Country Aging Context and Diagnostic Work (share of countries, %)

Source: Independent Evaluation Group calculations.

Note: The share of countries with evidence on the topics of interest—pension, gender, health, migration—is represented by the gray bar, and the blue bar indicates the share of countries with quality of evidence rated very good or excellent (share of all countries with very good or excellent evidence). Each indicator (old-age dependency ratio for pension, female labor force participation for gender, gap between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy for health, outmigration for migration) is assessed for 59 countries, using discontinuities in the observed distribution as cut-off points to determine categories proxying for the level of urgency. Old-age dependency ratio: ratio of population ages 65 and over per 100 population ages 15–64; female labor force participation: percentage of women ages 15–65 who are in the labor force; outmigration: estimated stock of people who have emigrated as a percentage of the population.

More extreme is the case of outmigration. Only 15 percent (2 out of 13) of countries from which more than 30 percent of the population has migrated abroad have relevant (and good-quality) country-specific diagnostic work analyzing the challenges that outmigration represents in terms of erosion of the quantity and quality of labor force and negative impact on population aging—and potentially on growth. This can be partly explained by country awareness. There are essentially two types of countries where outmigration is a key driver of population aging: countries with fertility rates that are still relatively high (such as Antigua and Barbuda, Grenada, Guyana, the Seychelles, and Suriname) and countries with fertility rates that are already below replacement level and are rapidly decreasing, many of which are in the Europe and Central Asia Region (such as Albania, Armenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro). Based on the IEG desk review, the CMU survey, interviews, and an in-depth study in the case of Jamaica, this first set of countries do not perceive themselves as aging.13 Small Europe and Central Asia Region countries experiencing increased outmigration are instead generally aware of the consequences in terms of aging. In the case of the Balkans, for instance, the negative impact of outmigration on population aging and economic growth was well analyzed in a 2015 report (World Bank 2015e). This report uses trends and projections at the regional and individual country levels and decomposition analysis to derive the impact of aging on economic growth in the absence of policy changes. The report concludes that the Balkan countries are not fully prepared for the aging of their population and may experience negative economic growth unless they adopt adequate policies to induce a change in behaviors (regarding, for example, not only participation in the labor force but also risky behaviors that decrease healthy life expectancy) and boost labor productivity.

Similarly, countries with low female labor force participation and those with the poorest health outcomes have low coverage in terms of diagnostic work in these two areas. Figure 2.5, panel b, shows that a very small percentage of countries where female labor force participation is low have World Bank analysis available on the interplay of gender issues and population aging; countries where female labor force participation is less of a problem are more likely to have solid pieces of gender analysis. Similarly, there is no correlation between a country’s urgency in addressing health issues (measured by lower life expectancy and large gaps between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy for either men or women) and the likelihood of observing substantial analysis on the issue (figure 2.5, panel c).

Limited Attention to Distributional Issues

Distributional issues are not regularly tackled in World Bank analytical reports, which limits the effectiveness of the diagnostics work in identifying specific vulnerabilities. IEG tracked whether empirical analysis has been carried out along five specific dimensions—gender, age (younger versus older cohorts), informality in labor markets, spatial (rural versus urban), and socioeconomic (poverty, education, class, and so on)—because the general literature highlights that groups defined by these characteristics can be affected by population aging in distinct ways.

Population aging has important implications for gender equality. Older women face a higher risk of poverty than men because of many factors. Since women have longer life expectancy and typically marry older men, they are more likely to outlive their husbands. Given their longevity, women have worse health than men in later life, so they are more likely to need care exactly when they are more likely to be widowed. Moreover, because women are less likely to be in formal employment and more likely to have a discontinued career due to childbearing, they are less likely to receive pension benefits and, if they do, they tend to receive lower pensions since women, on average, earn less than men and pay lower pension contributions. Promoting female employment is therefore essential to close gender gaps in both working age and old age (World Bank 2012c). A potential solution to shrinking labor force participation in aging societies is to support female employment. Yet there is more demand for women’s care work in aging societies, which (when unpaid) further limits women’s labor market participation or adds to women’s double burden of being responsible for both paid and domestic labor (World Bank 2015n). Adequate public policies are needed to provide long-term care and support female paid employment, thus addressing the specific vulnerabilities that an aging society entails for women (OECD 2017).

Gender issues are indeed the most frequently discussed distributional issue, present in just above half of all reports. The analysis of gender-related impacts of population aging varies depending on the main topic of the report (table 2.1). Although it may not be surprising that all eight reports on long-term care discuss gender, it is rather puzzling that barely one-third of social protection reports do. When the main topic is health, poverty, pensions, or the socioeconomic and demographic analysis of the country or Region, gender issues are more likely to be discussed, but this does not always occur.

Table 2.1. Percentage of Knowledge Products Discussing Distributional Issues, by Main Topic of the Report and Type of Distributional Issue

|

Main Topic |

Gender |

Intergenerational |

Formal-Informal |

Spatial |

Socioeconomic |

|

Economic growth (n = 21) |

38 |

29 |

33 |

38 |

33 |

|

Education or lifelong learning (n = 4) |

25 |

25 |

0 |

25 |

25 |

|

Long-term care (n = 8) |

100 |

25 |

38 |

63 |

50 |

|

Health (n = 10) |

60 |

10 |

0 |

20 |

40 |

|

Labor market (n = 14) |

50 |

21 |

29 |

43 |

29 |

|

Macroeconomics (n = 10) |

30 |

40 |

10 |

30 |

20 |

|

Pensions (n = 49) |

67 |

37 |

35 |

37 |

55 |

|

Poverty (n = 12) |

58 |

25 |

33 |

58 |

83 |

|

Social protection (n = 10) |

30 |

0 |

10 |

10 |

40 |

|

Socioeconomic or demography (n = 19) |

68 |

26 |

37 |

47 |

63 |

|

All (n = 157) |

57 |

27 |

28 |

38 |

48 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group calculations, based on review of analytical reports.

The overall limited attention to gender in analytical reports on aging is disappointing, since addressing gender gaps related to aging is one of the focus areas of the World Bank Group Gender Strategy (World Bank 2015n). Working on emerging, second-generation issues such as aging is part of the first objective of the strategy Improving Human Endowments (health, education, and social protection). Quite perplexingly, though, attention to gender decreased after the introduction of the gender strategy, which is only partially driven by a relatively higher prevalence of reports on economic growth over 2016–20 (in this most recent period, discussion of gender issues has decreased for each topic except social protection; table 2.2).

Table 2.2. Percentage of Knowledge Products Discussing Distributional Issues, by Year of Publication and Type of Distributional Issue

|

Time of Publication |

Gender |

Intergenerational |

Formal-Informal |

Spatial |

Socioeconomic |

|

2000 and earlier (n = 9) |

78 |

56 |

33 |

33 |

44 |

|

2001–05 (n = 10) |

50 |

20 |

0 |

0 |

50 |

|

2006–10 (n = 20) |

65 |

25 |

30 |

40 |

50 |

|

2011–15 (n = 59) |

65 |

31 |

34 |

42 |

56 |

|

2016–20 (n = 59) |

44 |

22 |

25 |

41 |

39 |

|

All (n = 157) |

57 |

27 |

28 |

38 |

48 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group calculations.

Population aging can also affect intergenerational inequalities. An increasing share of older people may pressure governments to revisit entitlements and make the social protection system less generous for the younger cohorts (to address the fiscal burden of aging), which implies a relatively more generous allocation of resources for the older generations—for health, social protection, long-term care, and pension benefits. Widening inequalities can affect the implicit social contract across generations and may be a source of social tensions.14 Ultimately, intergenerational inequalities depend on how a given society provides support for older people, including the extent of social programs, the prevalent familial systems and patterns of coresidence, and the allocation of savings and consumption across the life cycle (Lee 2016; Lee and Mason 2011).

Issues related to intergenerational inequalities, however, are discussed in only one-quarter of the reports. Those discussing pensions and pension reforms are more likely to address how different generations can be affected by system reforms. The regional report for Europe and Central Asia thoroughly discusses intergenerational issues, but it is a rare example. Golden Aging analyzes the interplay of aging and inequality—including inequality among and within generations—and depicts a complex picture of how behaviors change and policies respond (Bussolo, Koettl, and Sinnott 2015). The report considers inequalities originating in the labor market—driven, for example, by the different pension entitlements of low-wage, unskilled workers and highly skilled ones, and inequalities due to the lack of long-term care because of a change in the demographic profile, working patterns, and social norms, whereby younger people will be increasingly less available to provide support to older relatives in need.

Prevalence of informality in the labor market has a negative impact on contributory histories and productivity and hence on access to and adequacy of pensions, and, ultimately, poverty in old age: just above one-quarter of all reports discuss these issues. It is fair to expect that labor, pension, and poverty reports in particular would discuss informality. Barely one-third of reports in these three categories do. Yet a focus on informality can be illuminating. A couple of reports on Sri Lanka show that the de facto exclusion of informal workers from pension contributory schemes means that these workers will not have enough savings or pension to support themselves in old age (World Bank 2015j, 2019e). Although tackling informality is a complex task, designing the pension system in a way that it provides incentives for the informal workers to contribute could be an important first step—a point made also in a Bosnia and Herzegovina report, which shows that perverse incentives exist in the design of the pension system to move to informality after gaining a minimum of contributory history (World Bank 2007a).

Spatial inequalities are often analyzed in relation to long-term care and poverty but much less frequently in relation to other topics. Most reports in these two categories examine spatial inequalities. In China, spatial disparities between urban and rural areas are especially strong: an increasing number of older people are “left behind” in rural areas when their adult children migrate, which has disrupted the traditional coresidence arrangements and increased their vulnerability to poverty. The analysis of poverty and living arrangements of rural older people, the financial transfers they receive from migrant children, and the variability of those transfers has informed the design and evolution of China’s rural pension system (Cai et al. 2012; Giles, Wang, and Zhao 2010). In Romania, the uneven geographical distribution of both the aging population and social insurance coverage is likely to increase the risk of old-age poverty of many future older adults. Moreover, the concentration of older people in rural areas makes it particularly difficult for them to access health and long-term care services (Teșliuc, Grigoraș, and Stănculescu 2015).

Socioeconomic and poverty analysis of the older population is frequently carried out, especially in poverty assessments and poverty studies, but it has limitations. Poverty analysis in relation to age is not trivial. First, there are methodological issues. To correctly define how poor older people are, it is essential to understand the patterns of coresidence (including selection issues), the intrahousehold allocation of resources (which gets more complicated for extended households), and the level of needs of different categories (children, adults, older people) in calculating economies of scale (Deaton and Paxson 1998). Second, the analysis can be static (how many old individuals currently live in poor households) or dynamic (how vulnerable to poverty individuals are as they age, retire from the labor market, and become sick or disabled)—the latter being much more complex and data heavy but more interesting, as it allows for an assessment of how institutions, incentives, and policy reforms affect current and future vulnerability.

About half of the diagnostic work on aging has some analysis of poverty, but it is often a static analysis of the poverty of (currently) older people. Some older reports in the Europe and Central Asia Region and Sri Lanka have a strong focus on the living conditions of older people, as they discuss how to meet the needs of an aging population. More recently, the Belarus 2017 Poverty Assessment presents poverty data on older people (poverty rates of individuals with zero, one, or more than two older adults in the household) and includes an analysis of how pensions contribute to shared prosperity (Cojocaru and Matytsin 2017). Many of these studies do not address the methodological issues mentioned in the previous paragraph. The IEG review was unable to locate any longitudinal study on the vulnerability of middle-aged individuals and older workers to poverty in old age and on the role of the pension system and private savings in reducing that vulnerability.

The Data Challenge

The lack of adequate data may be an important explanation of the observed limitations of distributional analysis and sporadic attention to certain topics. In the World Bank’s empirical work, IEG observed great reliance on aggregate (macro) data and household survey data (Living Standards Measurement Study type), occasional use of Demographic and Health Survey data, and—only very rarely—specialized surveys. Although macro data and general household surveys provide relevant information, they also have limitations that prevent certain types of analysis. The data required for the analysis of several topics that were seldom or never addressed in the World Bank analytical work are discussed in this section.

Evidence on the links between aging and health is still limited on several fronts, including (i) the determinants of healthy aging; (ii) the evolution of health and functionality as people age; (iii) the variation of health inequalities among older adults over time and across and within countries; and (iv) the needs and preferences of older adults regarding health care and long-term care services. These are areas where granular and specialized data are needed, such as data on disability, functional dependency, cognitive status, mental health, and use of health care services.15 The paucity of data in these areas has been recognized in World Bank analytical work. For instance, the most recent regional report for Latin America and the Caribbean recognizes that limited data on functional capacities do not allow proper investigation of disability trends and demand for long-term care (Rofman and Apella 2020). To properly analyze care demand and supply in countries in Europe and Central Asia, a background paper to the Europe and Central Asia Aging report complemented existing data from household surveys and time use surveys with an original mixed-method data set gathered purposely for that study in seven countries in Europe and Central Asia, which demonstrates both the usefulness and the scarcity of data on care (Levin et al. 2015).

The analysis of vulnerability in the postretirement stage requires information about wealth. Wealth can top up pension income after retirement and can be annuitized into a flow of future incomes, in the same way pension assets are annuitized into a stream of pension benefits. The total income a person can rely on after retirement, and hence their risk of poverty, is the sum of pension benefits and the income derived from asset annuitization. Asset composition is also important, as annuitizing financial wealth is much easier than annuitizing housing wealth, which assumes the existence of reverse mortgage types of products, rarely available in thin financial markets.

The study of retirement behavior requires knowledge of pension contribution histories, employment and occupational histories, and health status. Individuals do not necessarily retire at the statutory retirement age but make decisions based on their health, accumulated pension entitlements, savings, and household composition, in addition to responding to institutional incentives, such as the provision of the social protection system. Those individual- and household-level variables allow for a better understanding of the future changes in the labor force and of the pool of retirees.

Cross-country data comparability is an issue. A seminal 2001 report of the US National Research Council highlighted the need to improve data on aging and stressed the importance of comparable cross-national and longitudinal data (National Research Council 2001). The same message has been echoed in the latest World Health Organization (WHO) report on aging and health (WHO 2015), which called for greater attention to cross-country data harmonization and standardization. Few countries have specific health surveys targeted at older adults that are truly comparable (box 2.1). Even when surveys were designed to ensure comparability, differences in the methodology, the questions included, or the wording of the questions may prevent cross-national comparisons or generalizations.16 Census and national household surveys sometimes (but not always) include a health section, but in those cases, cross-country comparison is even more difficult. Even when the same types of questions are included in health-specific surveys, the exact questions are often different, preventing comparisons. For instance, Uruguay is the only country in the Longitudinal Social Protection Survey to include both basic and instrumental activities of daily living in the section on functional dependency. The other Longitudinal Social Protection Survey countries include only basic activities, and these activities are not standardized across countries.

Longitudinal data are also often unavailable or difficult to access. Despite notable country efforts—some supported by the World Bank and other international organizations—longitudinal, good-quality, and comparable information on the health status of older people is either lacking or difficult to access, particularly in developing countries. Work history (longitudinal) data are available for some OECD countries but not for developing countries, with very limited exceptions (the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, for example).

Box 2.1. What Data Are Available to Better Understand Population Aging?

A set of harmonized surveys for the study of the multiple dimensions of aging is provided by the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe, covering 27 European countries and Israel; the US Health and Retirement Study; and the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. This model has been followed by other countries: Brazil, China, India, Ireland, Japan, Mexico, and the Republic of Korea. These data sets are not representative of the whole population but sample only middle-aged and retired people. However, they are extremely comprehensive, as they collect information on health, socioeconomic status (including income and wealth), work, retirement, pension, demographic characteristics, care, family transfers, and social networks and activities. Multiple waves have been conducted, which allows for longitudinal analysis.

The World Health Organization Surveys on Ageing and Health were carried out in several developing countries during 2006/07 and later in 2014. In Latin America, the Longitudinal Social Protection Survey also focuses on older people; it is available in Chile, Colombia, El Salvador, Paraguay, and Uruguay.

The harmonized Household Finance Consumer Survey conducted by the European Central Bank and covering the European countries is one of the very rare data sets that include both asset levels and income data. The data set has a longitudinal dimension and follows the same individual over time, allowing for an analysis of wealth accumulation and potential future income.

The Luxembourg Wealth Study is a database that includes detailed asset data for several countries, including some developing ones. The data sets are harmonized but lack a longitudinal dimension.

The World Value Survey includes measures of cultural values, attitudes, and beliefs toward gender, family, social tolerance and trust, and cultural differences and similarities among regions and societies. It has been collected since the 1980s and is currently adding its seventh round. It is available in 100 countries.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Other issues pertain to privacy and data manipulation. Administrative and medical records, which usually span the entire life of the individual, are a rich source of information; however, harmonization across countries may even require addressing issues of format and software compatibility. Privacy concerns usually surround the use of administrative records. Yet being able to link administrative and medical records to survey data would open immense research possibilities for evidence-based policy (National Research Council 2001). Similarly, the ability to access administrative data on pension contributory histories and (ideally) match them with survey data would provide tremendous potential for the study of retirement, pension accumulation, poverty, and more.

- The first paper mentioning aging that the Independent Evaluation Group identified was a paper almost 30 years old on the patterns of aging in Côte d’Ivoire and Thailand (Deaton and Paxson 1991).

- The report famously promoted the development of three pillars of old-age security: a publicly managed system with mandatory participation and a main goal of reducing poverty among the old; a privately managed, mandatory savings system; and a voluntary savings component.

- This reflects, albeit with some delay, the general recognition that population aging was not only confined to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries. The United Nations Political Declaration and Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing had recognized in 2002 that aging was “gaining real momentum in developing countries” and that this phenomenon had “profound consequences for every aspect of individual, community, national and international life” (United Nations 2002, para. 2).

- Many World Bank reports well describe the conditions that allow countries to take advantage of the first demographic dividend to secure the benefits of the second demographic dividend and turn aging challenges into opportunities. In the words of one of the most recent reports: “The first dividend occurs when the share of the working-age population in relation to other age groups reaches a maximum level. At this point, more labor is available and GDP [gross domestic product] per capita may grow faster. The second dividend is generated by the accumulation of capital and productivity increases that occur during the first dividend. Although the first dividend is temporary (it will disappear and reverse when population aging accelerates and dependency rates begin to grow), the second dividend may have a permanent positive impact on the economy” (Rofman and Apella 2020, 10).

- The report Pensions in the Middle East and North Africa stands out as it puts forward options for pension reforms for a generally young region with a still expanding labor force (Robalino 2005). The report focuses on the pension system—as opposed to the potential impact of demographic change on the economy at large—but it stresses the urgency of pre-empting a crisis and points to inter- and intragenerational distributional issues that need to be addressed before it is too late.

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development has recommended the elimination of mandatory retirement policies on the grounds that a worker’s age is not an indicator of productivity or employability (OECD 2015).

- The report Promoting Active Aging in Russia provides some qualitative evidence about attitudes toward older employees, and older workers’ preferences to continue in the workforce (Levin 2015). The results point to the willingness of older workers to stay in the labor market past the legal retirement age if flexible work arrangements and more childcare and long-term care options are available. At the same time, both workers and employers recognize that, while older workers can be more responsible and reliable, they often face age-related discrimination, job search difficulties, and skill mismatches.

- These global reports are not necessarily aging reports; several are on pensions and social protection.

- The Active Aging Index is a joint product of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Population Unit; the European Commission Directorate General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion; and the European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research in Vienna. It is a composite measure, obtained by aggregating scores from four domains: (i) employment, (ii) participation in society, (iii) independent, healthy, and secure living, and (iv) enabling environment (see Karpinska and Dykstra 2015).

- The number of reports is used as a proxy for the World Bank’s extended attention (over time) to a country demographic situation.

- Figure 2.4 uses the old-age dependency ratio to rank countries from the youngest to the oldest; the results are robust to using the proportion of the population over age 65 instead of the old-age dependency ratio. These ratios are not used in a normative sense (that is, to endorse one specific definition of aging over another) but uniquely for convenience, as they are widely adopted.

- For this analysis, the number of reports has been compacted into a country-level dummy indicating the presence or absence of evidence of a certain quality on a certain topic (see appendix D for details).

- Jamaica’s fertility rate is already below replacement rate, but aging is still not perceived as an urgent priority in that country.

- The World Development Report 2019: The Changing Nature of Work observes that social contracts in Eastern Europe and East Asia would need to create mechanisms to sustainably finance the protection and care of older people (World Bank 2019h).

- A US National Research Council report recommends that countries follow a system of “hierarchy of data collection modules,” where minimum sets of data are defined for each module, from basic data to increasingly elaborated data sets, that guarantee the comparability across countries. According to the report, these data sets should include, at least, “the frequency and rates for (1) deaths and their major causes; (2) important acute and chronic medical conditions and their major manifestations; (3) measures of important self-reported health status; (4) population levels of physical, social, and mental function; (5) preventive and health promotional behaviors; and (6) important disabilities. In addition, minimum health care information for older persons should include (1) utilization rates for important types of health services, including institutional and home-based care; (2) personal and family expenses for formal health services; (3) rates of use of medications and devices; (4) major cultural influences on the concept of health and the use of health services (such as gender, ethnicity, geographic residence, and socioeconomic status); and (5) the use of informal and alternative and complementary health care services” (National Research Council 2001).

- Projects to improve cross-country comparability of aging and retirement surveys are underway. See Boersch-Supan (2016).