World Bank Engagement in Situations of Conflict

Chapter 3 | Identifying and Addressing Conflict Risks to Operations

Highlights

There is a growing tendency for investment projects in conflict-affected areas to identify and address fragility factors and conflict drivers; include adaptive, conflict-sensitive design and implementation mechanisms; and mitigate exposure risks (in effect, to “lean in” to conflict). Likewise, fewer investment projects avoided or neglected conflict issues. The existence of a Risk and Resilience Assessment encourages “leaning in.” Notwithstanding this improvement, the number of projects that consider conflict dynamics in conflict-affected areas remains low in Agriculture and Food, Energy and Extractives, and Transport, especially in the Sahel.

When faced with security-related implementation challenges, less than 20 percent of projects in the portfolio analyzed that had initially avoided or neglected conflict used restructuring or flexible mechanisms to adapt project design. Staff cite pressure to disburse as a key reason for this behavior.

Although the World Bank swiftly rolled out emergency coronavirus pandemic responses to all conflict-affected countries with an active portfolio, only half of these operations referenced conflict risks, raising the specter of potentially exacerbating conflict drivers. It is acknowledged that the COVID-19 response projects were developed during unprecedented circumstances. However, the pandemic has presented particular risks for countries already experiencing a high degree of conflict or instability, contributing to a multiphase, complex emergency—a situation that differs from non-conflict-affected countries.

To determine the nature and extent to which World Bank investment operations identify and address conflict risk, this evaluation conducted a project-level conflict sensitivity analysis supported by a selectivity framework that rests on the spatial intersection between project locations and conflict areas. The analysis was conducted for projects approved since FY10 mapped to five key Global Practices: Agriculture and Food; Energy and Extractives; Social Protection; Transport; and Urban, Disaster Risk Management, Resilience, and Land (appendix A). The Global Practices were chosen because of their physical footprint and significance in the country portfolios. (Health and education were covered in the World Bank’s COVID-19 response analysis; see the Identifying and Managing Conflict Risks as Part of the COVID-19 Response section later in this chapter.) Overall, 84 percent of all projects approved since FY10 were found to be operating in conflict-affected areas.

To assess and report on projects’ relative conflict sensitivity, the evaluation then developed a taxonomy containing four mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive categories to systematically assess conflict sensitivity:

- Lean in to conflict. Documentation (i) identified conflict drivers; (ii) explicitly addressed these drivers in project design (theory of change, purpose, scope, location, targeting); and (iii) included adaptive implementation mechanisms, including mechanisms to mitigate exposure risks to assets and people.

- Minimize exposure risk. Documentation (i) identified conflict drivers and (ii) included implementation mechanisms to mitigate risks to assets and people.

- Avoid conflict. Documentation (i) identified conflict drivers, but (ii) sought to avoid engaging in conflict-affected areas or with conflict-affected populations, and as such did not explicitly address drivers or include adaptive mechanisms.

- Neglect conflict. Project documentation neither identified nor addressed conflict issues.

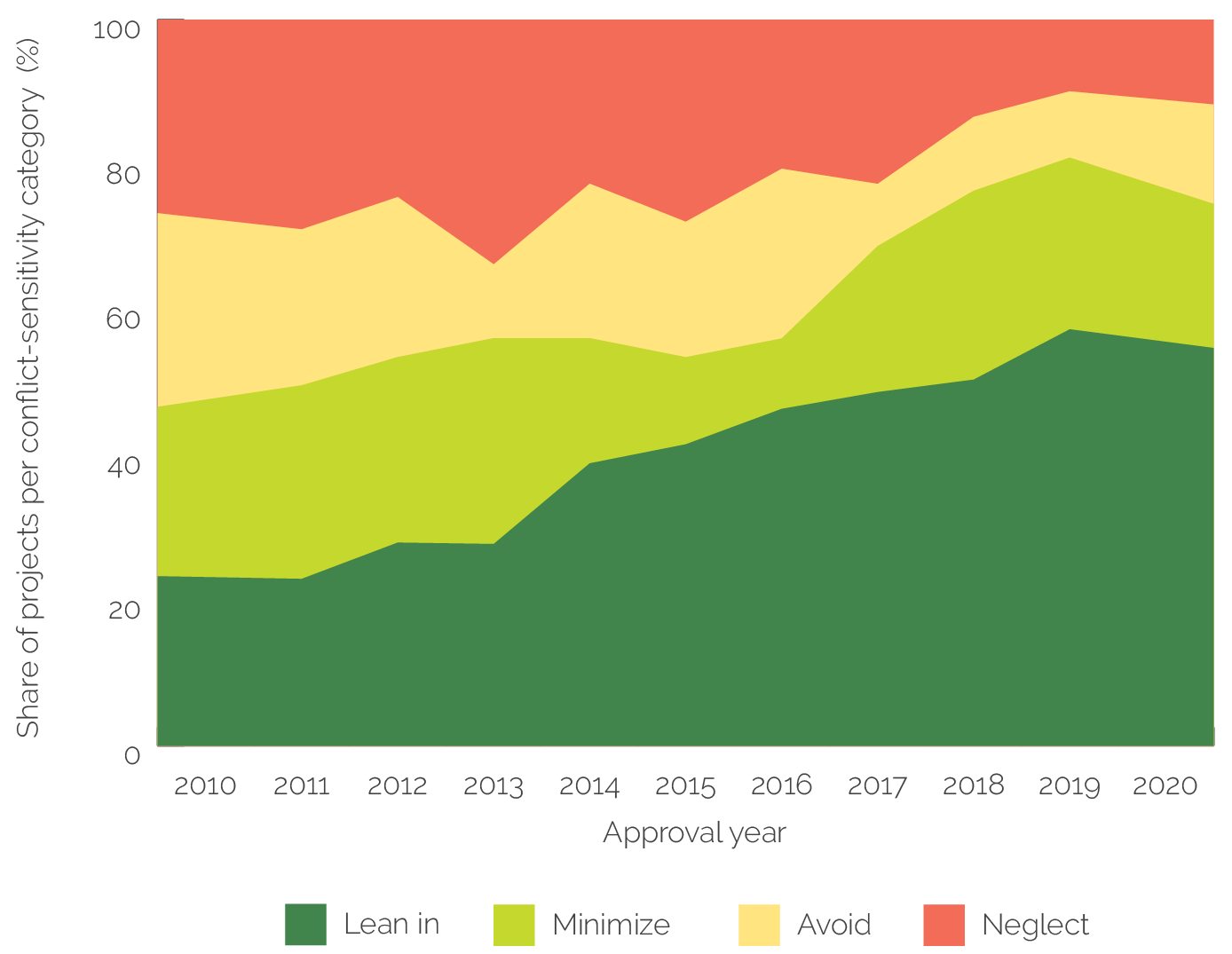

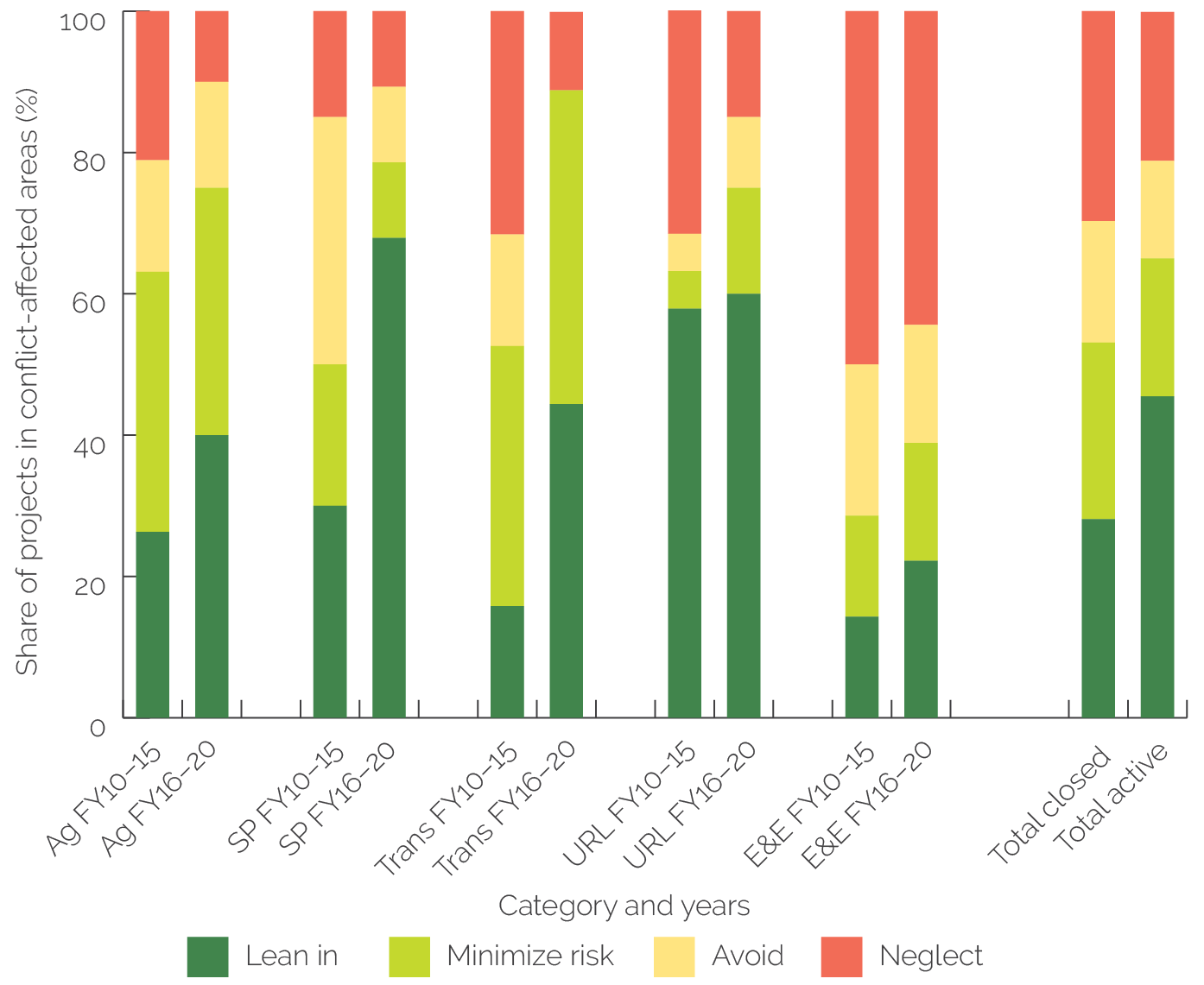

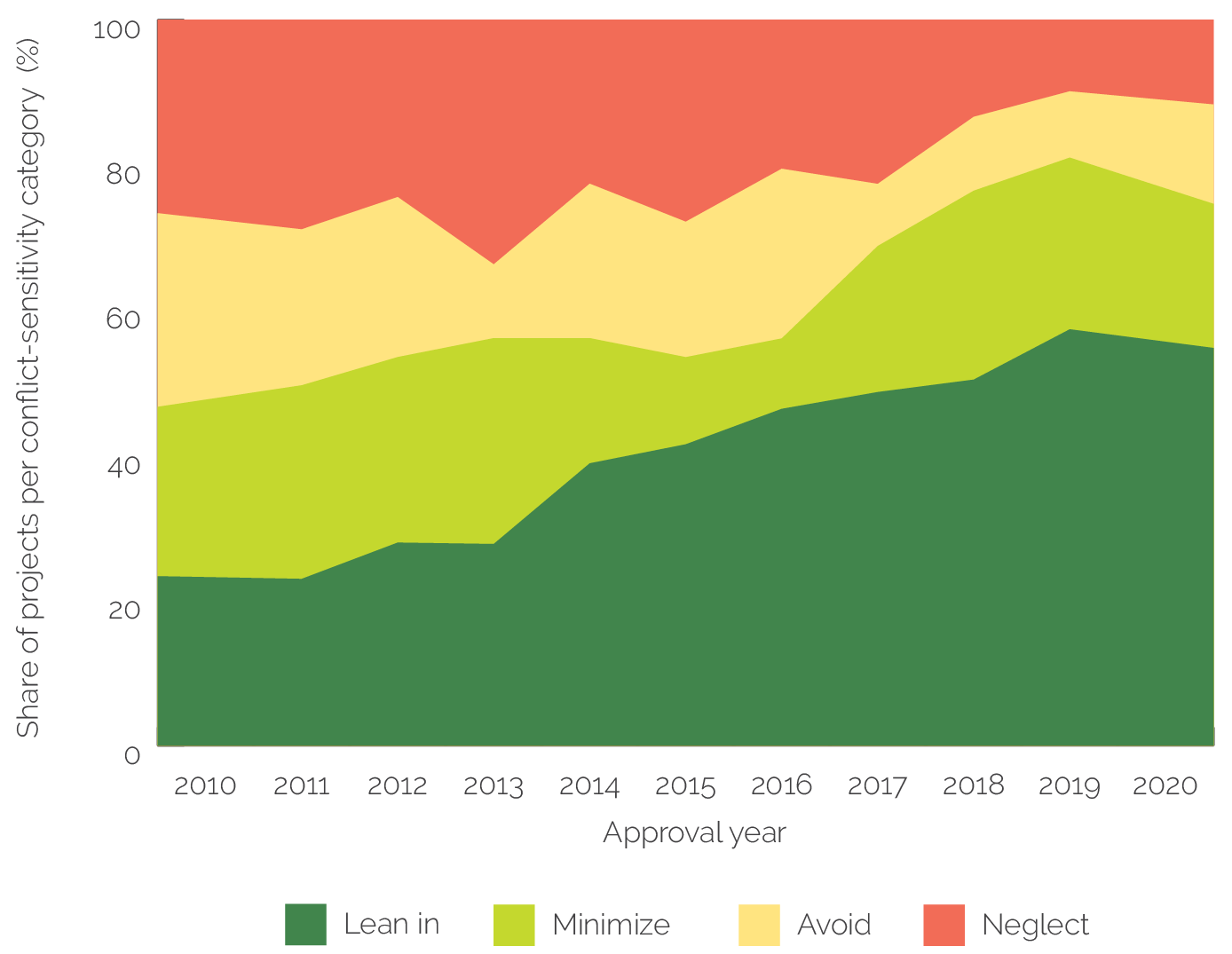

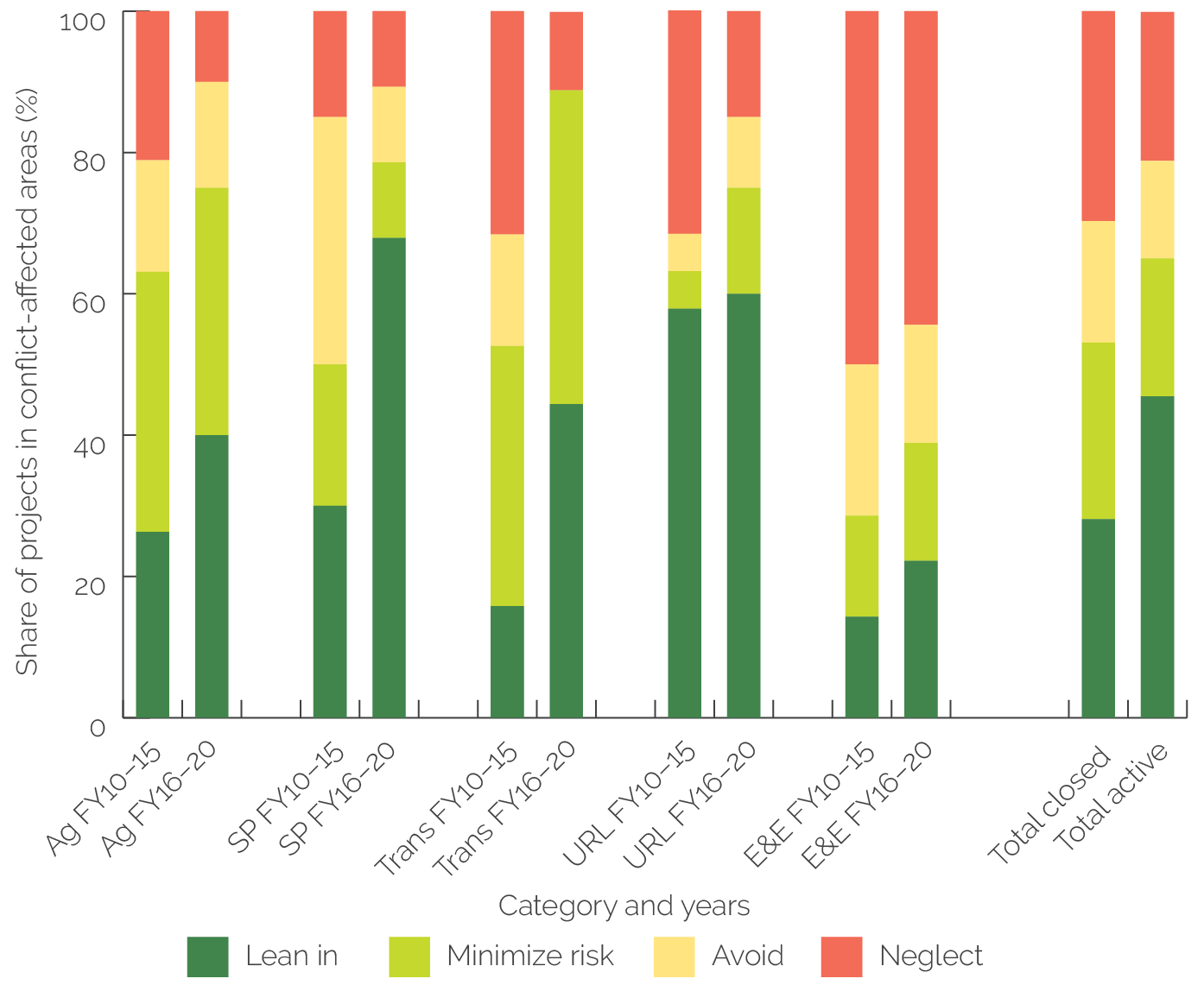

There is a growing tendency for projects that operate in conflict-affected areas to lean in to conflict. Two-fifths of the assessed portfolio were found to lean in to conflict, with an uptick in this behavior over time (figure 3.1). Compared with those approved in the first half of the evaluation period, projects approved during the second half were 50 percent more likely to identify and address conflict drivers as part of their project theory and design; include adaptive, conflict-sensitive design; and include implementation mechanisms and mechanisms to mitigate exposure risks to assets and people (figure 3.2). This trend was most pronounced for Transport, Agriculture and Food, and Social Protection, although ratios remained low for Transport and Agriculture and Food. High to begin with, Urban, Disaster Risk Management, Resilience, and Land’s “project” ratio stayed the same, except for disaster risk management projects that did not have a conflict lens. The number of Energy and Extractives projects operating in conflict-affected areas that lean in was low throughout (lean-in projects are shown in green in figure 3.2), and there has been only modest improvement in the Sahel since 2019, due to a lack of financial support and decentralized technical expertise.

Figure 3.1. Share of Projects per Conflict Sensitivity Category per Approval Year, Three-Year Trailing Averages

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Figure 3.2. How Investment Projects in Conflict-Affected Areas Identify and Manage Conflict Risks (across Five Global Practices)

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: N = 186. Ag = Agriculture and Food; E&E = Energy and Extractives; FY = fiscal year; SP = Social Protection; Trans = Transport; URL = Urban, Disaster Risk Management, Resilience, and Land.

Specifically, projects lean in to conflict in a variety of ways. These projects target conflict-affected populations, including by reducing tensions between refugees and host communities or between the state and ethnic or marginalized communities. Some are better at articulating how they will ensure transparency regarding beneficiary targeting (for example, youth) to address tensions, including those potentially caused by aid. Two-thirds of this portfolio engage partners, including the UN and nonstate actors, for implementation support. They often put in place alternative mechanisms for monitoring and supervision, such as third-party monitoring or other information and communication technology–enabled solutions, and some engage in innovative risk monitoring (box 3.1). A few projects that lean in also support conflict prevention through enhanced grievance redress (designed to monitor and address conflict drivers) or local conflict resolution mechanisms, or by addressing land disputes.

Box 3.1. Examples of Projects That Lean In to Conflict

In Afghanistan, National Solidarity Project Additional Financing (fiscal years [FY]10–15) introduced conflict-sensitive targeting by restructuring the project to reach highly insecure areas. It provided block grants to communities experiencing funding shortfalls driven in part by deteriorating security conditions. The project developed a high-risk area strategy to enable flexible implementation, including subcontracting implementation to local nongovernmental organizations and using a distance model that relied on community member implementation.

In Somalia, the Shock Responsive Safety Net for Human Capital Project (FY20–present) established clear and objective criteria to ensure fair access to the safety net and to mitigate tensions regarding distribution in highly conflict-affected areas. The project partners with the World Food Programme and the United Nations Children’s Fund for implementation and monitoring support.

In the Republic of Yemen, the World Bank partnered with the United Nations Development Programme to maintain support for service delivery after war broke out and after the collapse of the Yemeni state through the Yemen Emergency Crisis Response Project (FY17–present). Partnering enabled the World Bank to target and reach conflict-affected communities in contested areas and permitted the World Bank to reduce risks to project staff and assets, since the United Nations can communicate with third parties. Within 18 months, the approach enabled the transfer of cash to one-third of the population.

In South Sudan, the Emergency Food and Nutrition Security Project (FY17–19) adapted its implementation arrangements for its cash-for-work component. As discovered during implementation, some beneficiaries could not work because of conflict, so the project was restructured to allow for direct transfers to these populations rather than requiring work.

Sources: World Bank 2016d, 2017a, 2017h, 2019f, 2019g.

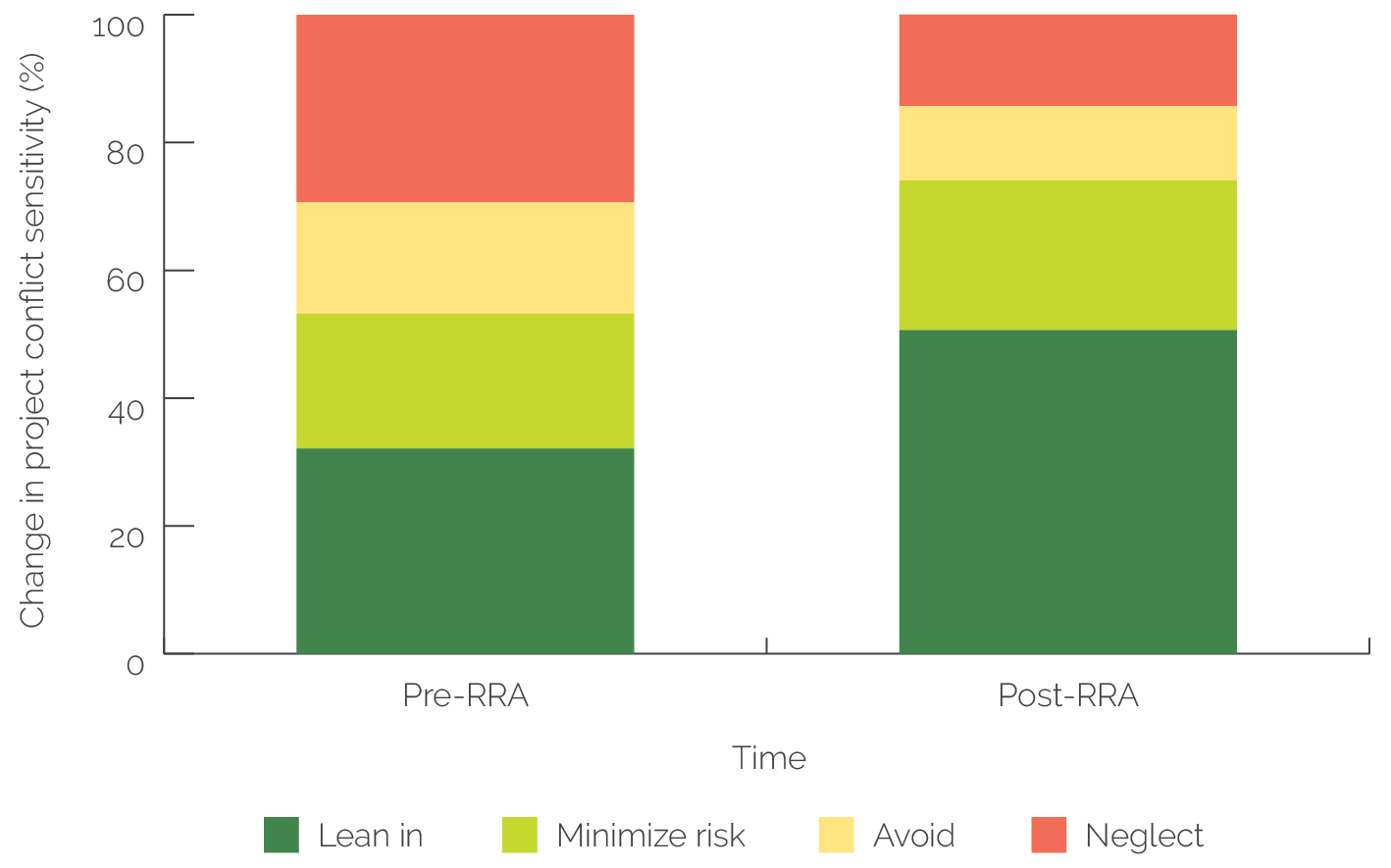

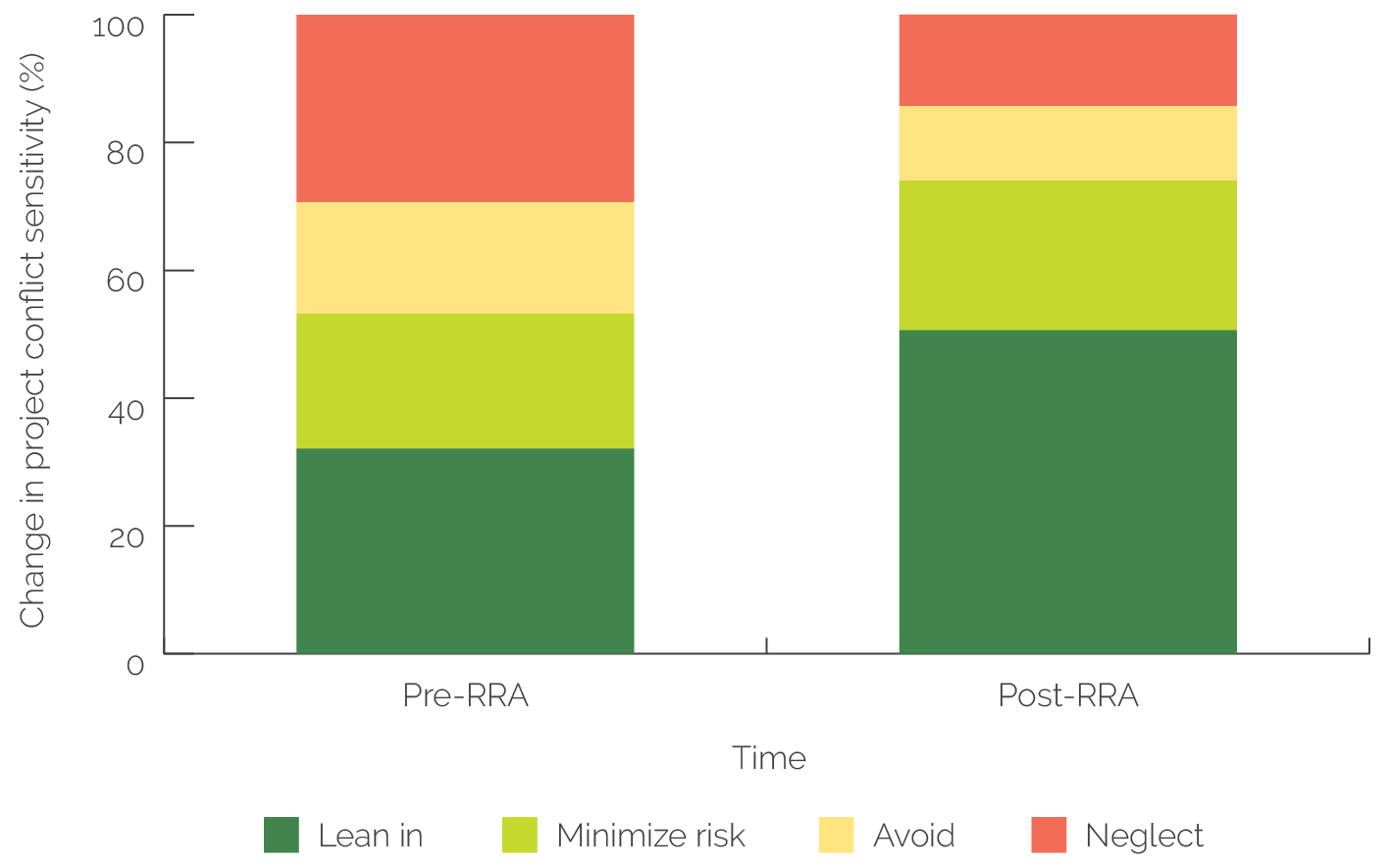

The existence of an RRA in a country encourages leaning in because it makes the design of subsequent investment projects more likely to integrate conflict sensitivity. Operations approved in a country after the development of an RRA tend to lean in to conflict more than those approved before an RRA (figure 3.3). One-third of assessed projects, approved before an RRA, leaned in, whereas this was true for one-half of projects approved after an RRA. Operations that lean in before an RRA were located in countries that have had protracted subnational conflict and that have been assisted by a conflict expert—countries in which conflict is already being mainstreamed into country operations. To be sure, before the recent mandating of RRAs, the decision to conduct an RRA was aligned with country management awareness and support to integrate conflict issues into its engagement strategy; as such, the RRA is a cause and an effect of a country program shift toward conflict awareness.

Figure 3.3. Percentage of IPF across Five Global Practices That Lean In to Conflict before and after RRA

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: IPF = investment project financing; RRA = Risk and Resilience Assessment.

Over time, there are fewer investment projects operating in conflict-affected areas that do not identify or address conflict issues in design; that is, fewer neglect conflict. The percentage of projects that neglected conflict issues—that neither identified conflict issues nor adapted project activities to address them—declined from 28 to 19 percent from the first to the second half of the evaluation period (the red in figure 3.2). Agriculture and Food and Transport projects showed the strongest improvement (decline in the number of projects neglecting conflict); Energy and Extractives projects showed no change over time in relation to the number of projects that neglect conflict issues. Projects in the Sahel also pulled down averages; research is needed to understand the factors contributing to this trend (besides the fact that the conflict zone in these countries has expanded rapidly over the past several years).

Fewer investment projects in conflict-affected areas sought to ring-fence themselves from the effects of conflict; that is, fewer projects are avoiding conflict. The propensity to try to avoid conflict—avoiding an area after having identified conflict drivers and their likelihood to further undermine development gains—declined from 17 to 11 percent between the first and second half of the evaluation period (the yellow in figure 3.2). One factor that may explain why projects in conflict-affected areas are less likely to avoid conflict is that almost half (43 percent) of those projects that sought to avoid conflict reported experiencing conflict-related implementation challenges. This was especially true for projects implemented at the national level, of which 75 percent avoided conflict but later experienced conflict. Even so, many projects in this category (and the category of neglect) did not report on conflict-related challenges (this is especially true for the Energy and Extractives sector), even though the data show that these projects were operating in conflict-affected areas. Furthermore, projects in both cohorts (avoid and neglect) are least likely to restructure or use other flexible mechanisms (as determined through a project document review) when faced with conflict-related implementation issues, as compared with two-thirds of projects that leaned in, over the evaluation period.1

Twenty-two percent of investment projects in conflict-affected areas did the minimum: they included adaptive implementation mechanisms to mitigate exposure risks to assets and people, but they did not address conflict drivers in their design or project theory (the light-green in figure 3.2). Projects operating in conflict-affected areas need to—at a minimum—mitigate exposure risks to assets and people. Mechanisms include routine risk monitoring—by engaging civil society and nonstate actors—and adapted supervision mechanisms, including third-party monitoring and other information and communication technology–based solutions.

Addressing Risks through Upstream Operational Support from Corporate Security

In some situations, task teams have benefited from actionable, upstream support directly from Corporate Security specialists for project preparation and implementation in situations of conflict. A survey of World Bank security specialists found that only a few had directly supported task teams with such work (which is distinct from security guidance regarding mission travel) in Afghanistan, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, and Somalia (box 3.2); the rareness of such work is not surprising because it lies outside of Corporate Security’s mandate (the Bank Group duty of care does not extend to project implementation personnel and activities). This work is largely demand driven: Task team leaders opt to reach out to security specialists for assistance in preparing and implementing projects using a security lens. In the words of one security specialist, “an ideal relationship [between a country security specialist and their management team] might see more regular [country office] requests for analytical input, formal products that serve specific project team needs, in addition to more informal touchpoints between the analyst and the office teams.” Some of these cases have led to critical value added for project design or implementation. Yet, since such upstream support falls outside of Corporate Security’s mandate, it is not expected it will expand.

Box 3.2. Examples of Upstream Operational Support from Corporate Security

In Mali, a security specialist developed a threat-based analysis to inform design of a project for the dredging of the Niger River Delta, the results of which convinced the task team leader to downsize certain activities pending an improvement in the security environment.

In Somalia, a security specialist conducted analysis and provided security guidance on the potential risks of a projected World Bank–executed roads project in Mogadishu, the results of which led to the dropping of the project because of security risks.

Sources: Interviews with World Bank Group staff and management; interviews with and survey of Corporate Security staff.

Identifying and Managing Conflict Risks as Part of the COVID-19 Response

Although all conflict-affected countries with active lending received some form of COVID-19 response support, only half of the portfolio—of both restructured and newly approved projects—included a consideration of conflict risks. As of 2020, the World Bank had approved 42 projects and restructured 29 existing projects to respond to COVID-19 in conflict-affected countries (of which 64 are IPF, 4 are DPF, and 3 are Program-for-Results). Only 57 percent of the newly approved and half of the restructured projects include references to conflict risks in their Project Appraisal Documents. For restructured projects, mentions of conflict risk and associated management measures tended to exist only if they had been analyzed by the parent project (in the absence of this initial risk identification, no new analysis was conducted for restructured projects). Analysis gaps were especially found in Eastern and Southern Africa (including in Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Madagascar, and Sudan).

Although it is acknowledged that the COVID-19 response projects were developed during unprecedented circumstances, for countries already experiencing a high degree of conflict or instability, COVID-19 is best understood and responded to as a multiphase complex emergency. COVID-19 has presented second- and third-order risks —especially security risks—for countries already experiencing a high degree of conflict or instability, a situation that differs from non-FCV countries. For those projects that did not consider conflict dynamics in design, they should integrate this analysis into their adaptive management and their monitoring and evaluation.

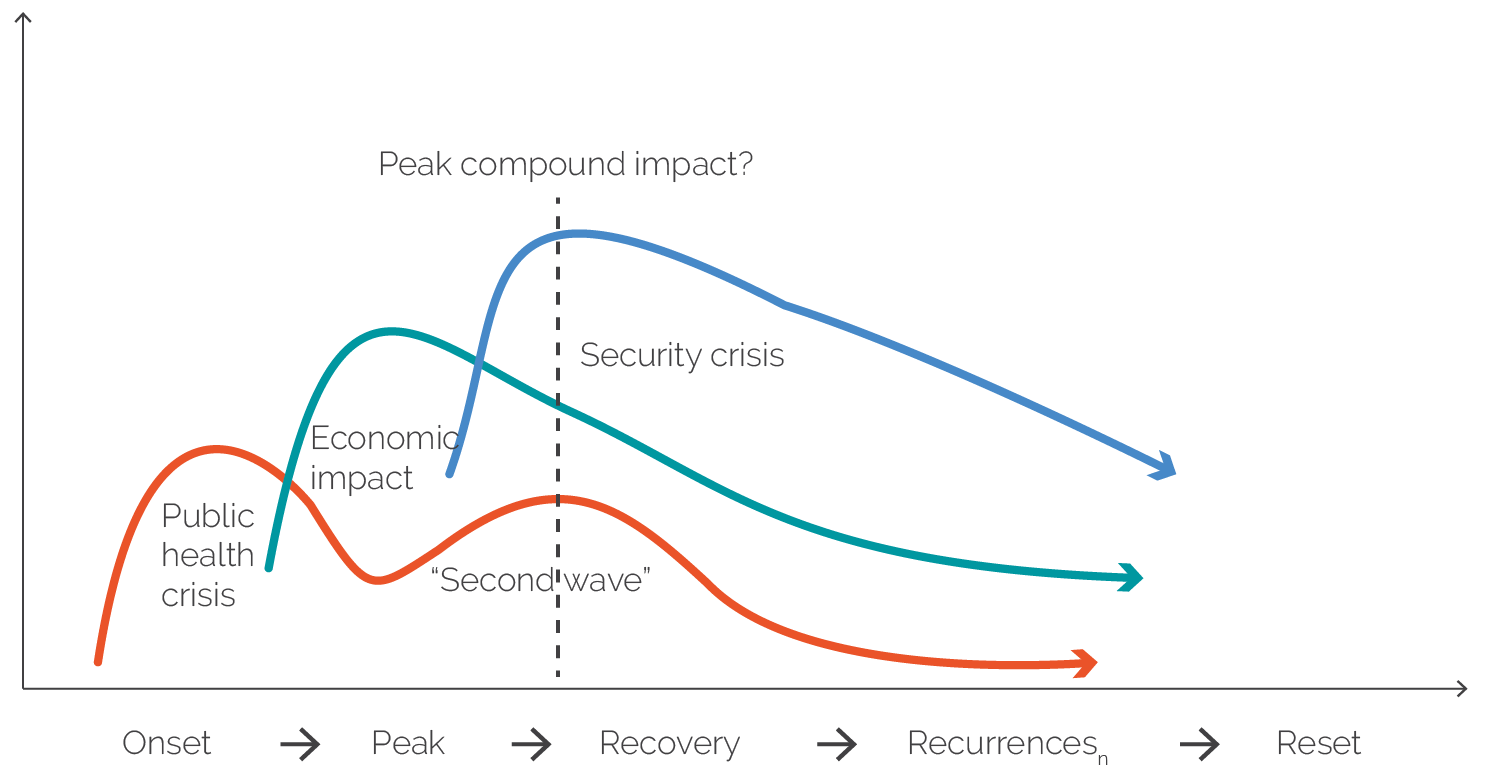

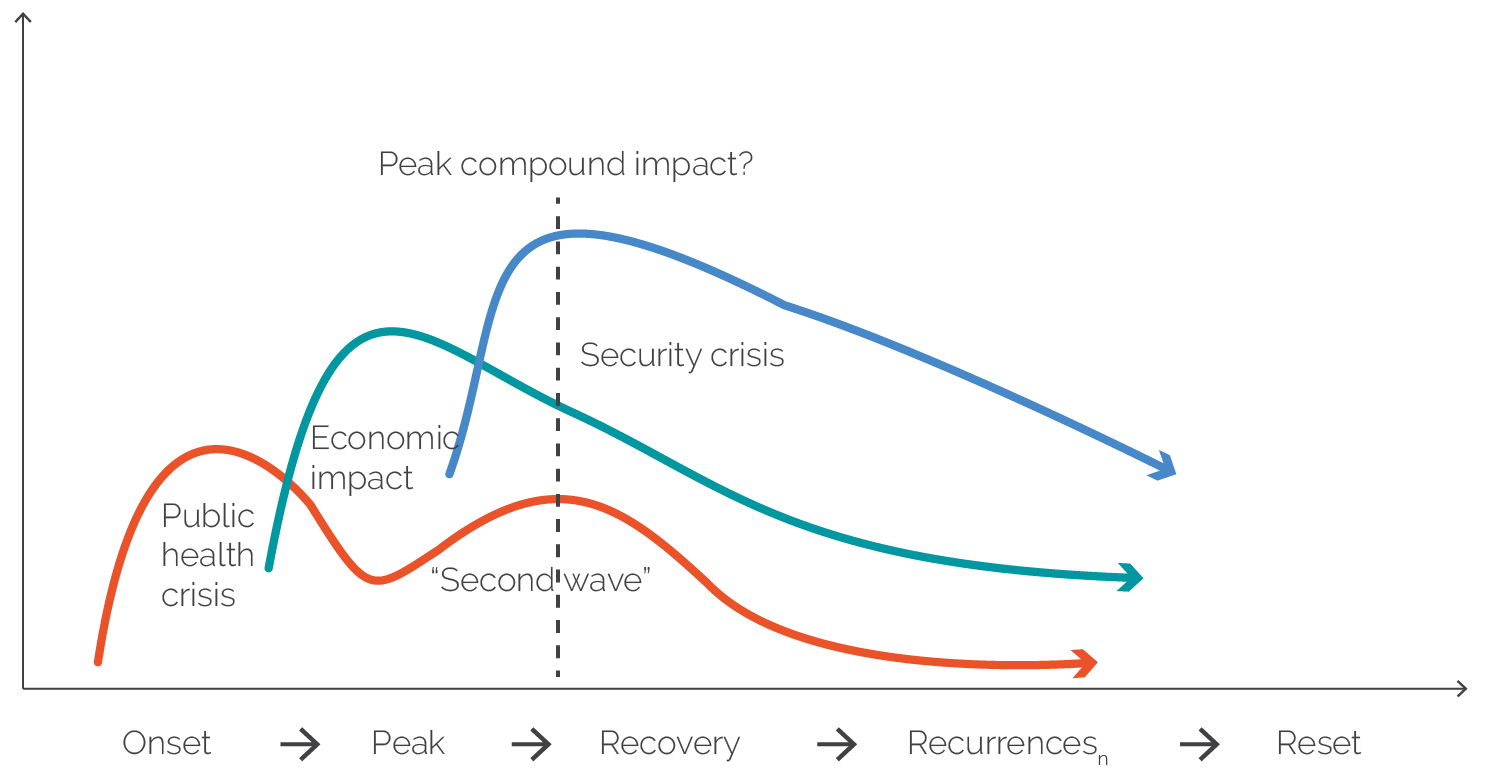

Conflict-affected countries experience COVID-19 differently (Cordillera Applications Group 2020). Although these countries are experiencing a wave of public health effects—followed by a wave of economic impacts—many also experience a wave of security impacts (figure 3.4). These waves overlap, have mutually reinforcing effects, and occur in a sequence of onset, peak impact, recovery, recurrence(s), and reset. Where multiple waves occur, there are complex nonlinear ripples of health, economic, and security impacts with which to contend.

Figure 3.4. Impacts of COVID-19 as a Multiphase Complex Emergency

Source: Cordillera Applications Group 2020.

When addressing the impact of COVID-19, many projects did not include special considerations for conflict-affected countries such as those discussed in the following paragraphs.

The impact of the disease may be less damaging than the effects of economic disruption. Conflict-affected countries whose populations depend on remittances are especially vulnerable. When the livelihood of diasporas is compromised because of lockdowns, job loss, or other pandemic effects, the disruption of remittances can create significant hardship. In the initial stages of the pandemic, remittances to Somalia—a country in which half of all households rely on remittances—have fallen by 15 percent (Samantar 2020). Since then, however, remittances have rebounded overall and have been thought to have buffered COVID-19–related economic impacts in some remittance-receiving countries.

Contested governance at the subnational level complicates pandemic response. Countries with areas controlled or contested by nonstate armed actors are likely to have difficulty tracking disease or delivering health services. When development actors are obliged to work only with governments, they may be unable to access areas or may not be seen as impartial. These risks should be considered ex ante.

Internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees are vulnerable because they have low access to clean water, sanitation, and nutrition and have difficulties practicing social distancing. Crowded IDP camps lacking in sanitation and medical facilities pose an outbreak risk. Likewise, refugees returning or expelled from countries may represent a health risk (or be perceived as such) if entering from affected areas and can also burden overstretched medical systems.

Perhaps counterintuitively, conflict-affected countries already experiencing high levels of violence, economic disruption, and social polarization may have a protective (or harm-reducing) effect in relation to the pandemic. Economic exclusion can dampen economic shocks associated with COVID-19. For example, a high proportion of farmers engaging in subsistence agriculture limits the welfare impact of market and supply chain disruptions. Also, conflict, which reduces mobility, can slow the virus’s spread.

- A good example of a project that used restructuring to adapt its design is the Cameroon Multimodal Transport Project, which began in fiscal year 2014 and supported road building in areas where there was eventually active fighting between Cameroonian Armed Forces and Boko Haram. Although a social assessment carried out in May 2017 rated the local security threats as low, the security situation was volatile, and implementation faced mounting security challenges. The project opted for a level 2 restructuring, to institute a permanent security unit to protect the site, a security monitoring commission staffed with senior military officials, and an independent observatory to assess security conditions where the road was being built.