World Bank Engagement in Situations of Conflict

Chapter 1 | Background and Context

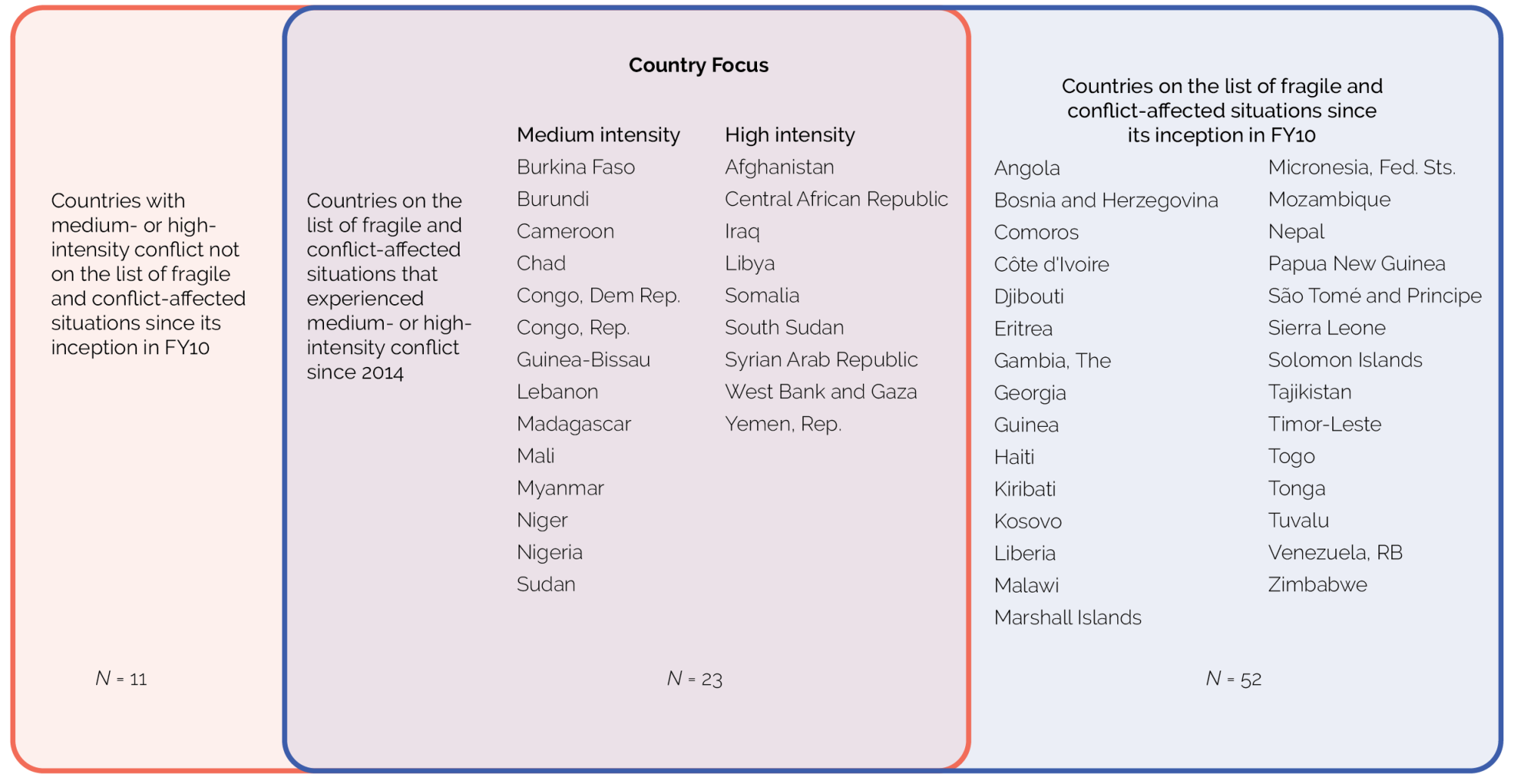

Achieving poverty reduction and shared prosperity increasingly depends on the World Bank’s ability to effectively engage in conflict-affected environments. The World Bank Group has made a strong commitment to address the rising levels of poverty and human suffering occurring in conflict-affected countries. Globally, conflict is becoming more complex and intense: There were twice as many annual civilian deaths due to conflict in 2016 than in 2010. The increasing intensity of warfare presents significant risks to an expanded volume of World Bank commitments in conflict-affected situations (figure 1.1). Conflict actors are also more diverse—including militias, armed trafficking groups, and violent extremist groups—and are becoming increasingly internationalized; consequently, working in conflict-affected situations has become more complex (UCDP 2017; World Bank and United Nations 2018a). Complicating the battle against extreme poverty is the interaction among conflict, climate change, and the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19), which has resulted in a reversal of poverty eradication gains for the first time in a generation.

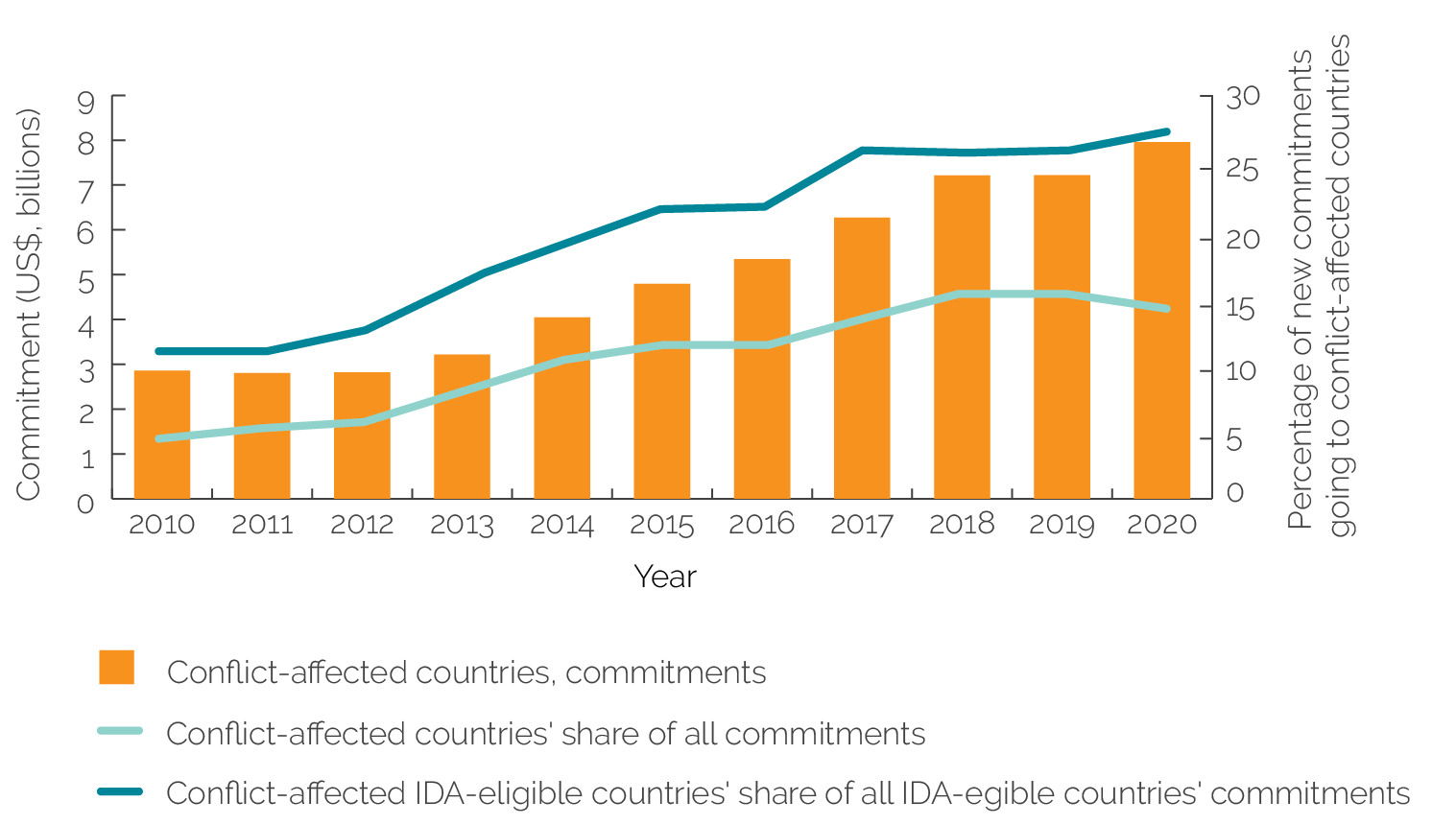

Figure 1.1. Increasing World Bank Engagement in Conflict-Affected Areas

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (database), https://acleddata.com; Uppsala Conflict Data Program (database), Uppsala University, https://www.pcr.uu.se/research/ucdp.

The World Bank recognizes that, to support its mission to reduce extreme poverty, it needs to adapt the way it works in conflict-affected situations. First, it has done this by adopting the new World Bank Group Strategy for Fragility, Conflict, and Violence 2020–2025, which lays out new forms of engagement along the conflict spectrum (World Bank 2020f). These include (i) engaging upstream to prevent violent conflict and interpersonal violence; (ii) remaining engaged during conflict and crisis situations; (iii) helping countries transition out of fragility; and (iv) mitigating the spillovers of fragility, conflict, and violence (FCV). Second, it introduced a new methodology for classifying conflict-affected countries within the World Bank’s fragile and conflict-affected situation (FCS) list, distinguishing between countries affected by conflict and those with high levels of institutional and social fragility, setting the World Bank on a path to better identifying and applying a customized set of tools, in line with prevailing realities and institutional capabilities (Milante and Woolcock 2017).1 Third, it updated its conflict analysis (risk and resilience) methodology and updated relevant operational policies (for example, Operational Policy [OP] 2.30, on development cooperation and conflict) based on lessons from experience and in line with the principles set out in the FCV strategy. Fourth, it is deepening and formalizing its partnerships with the United Nations (UN) and humanitarian agencies, including through memorandums of understanding, along the development–security–peace-building nexus. Fifth, it continues to provide increased financing tailored to various phases of conflict and fragility. New commitments directed toward countries and territories that have experienced medium- to high-intensity conflict since 2014—the focus of this evaluation—have increased steadily in nominal terms and, as a share of all new commitments during fiscal years (FY)10–20, have more than doubled.

Over the period of this evaluation (FY10–20), the World Bank provided increased financing to conflict-affected—and fragile—countries both by changing the International Development Association (IDA) performance-based allocation formula and through a suite of innovative instruments tailored to various phases of conflict. Building on lessons from the 17th Replenishment of IDA, the 18th Replenishment of IDA (IDA18) Risk Mitigation Regime and Turnaround Regime (TAR), and recent experiences in the Republic of Yemen and elsewhere, the World Bank created an FCV envelope through the 19th Replenishment of IDA (IDA19), which provides additional allocations to eligible countries in conflict-affected situations (World Bank 2019c). These include the Prevention and Resilience Allocation, which can increase a country’s performance-based allocation by 75 percent (up to $700 million); the Remaining Engaged during Conflict Allocation, which can increase a country’s performance-based allocation up to $300 million; and the Turnaround Allocation (TAA, a successor to IDA18’s TAR), which can increase a country’s performance-based allocation by 125 percent (up to $1.25 billion). Complementing the FCV envelope, the Window for Host Communities and Refugees supports pillar 4 of the FCV strategy (mitigating the externalities and impacts of FCV); other IDA windows, including the Crisis Response Window and Arrears Clearance, provide additional resources. Apart from IDA, the World Bank has also established the Global Concessional Financing Facility for refugee-hosting middle-income countries.

To enable it to effectively engage in conflict-affected situations, the World Bank has partnered across the humanitarian–development–peace-building nexus. This includes engaging in various forms of cooperation and coordination with development partners, the UN, and humanitarian agencies, and in interactions with nonstate actors that are a party to conflict. The World Bank has formalized its relationships with several UN agencies. It has also updated its OP2.30, “Development Cooperation and Conflict.”2

Purpose, Scope, Portfolio, and Evaluation Questions

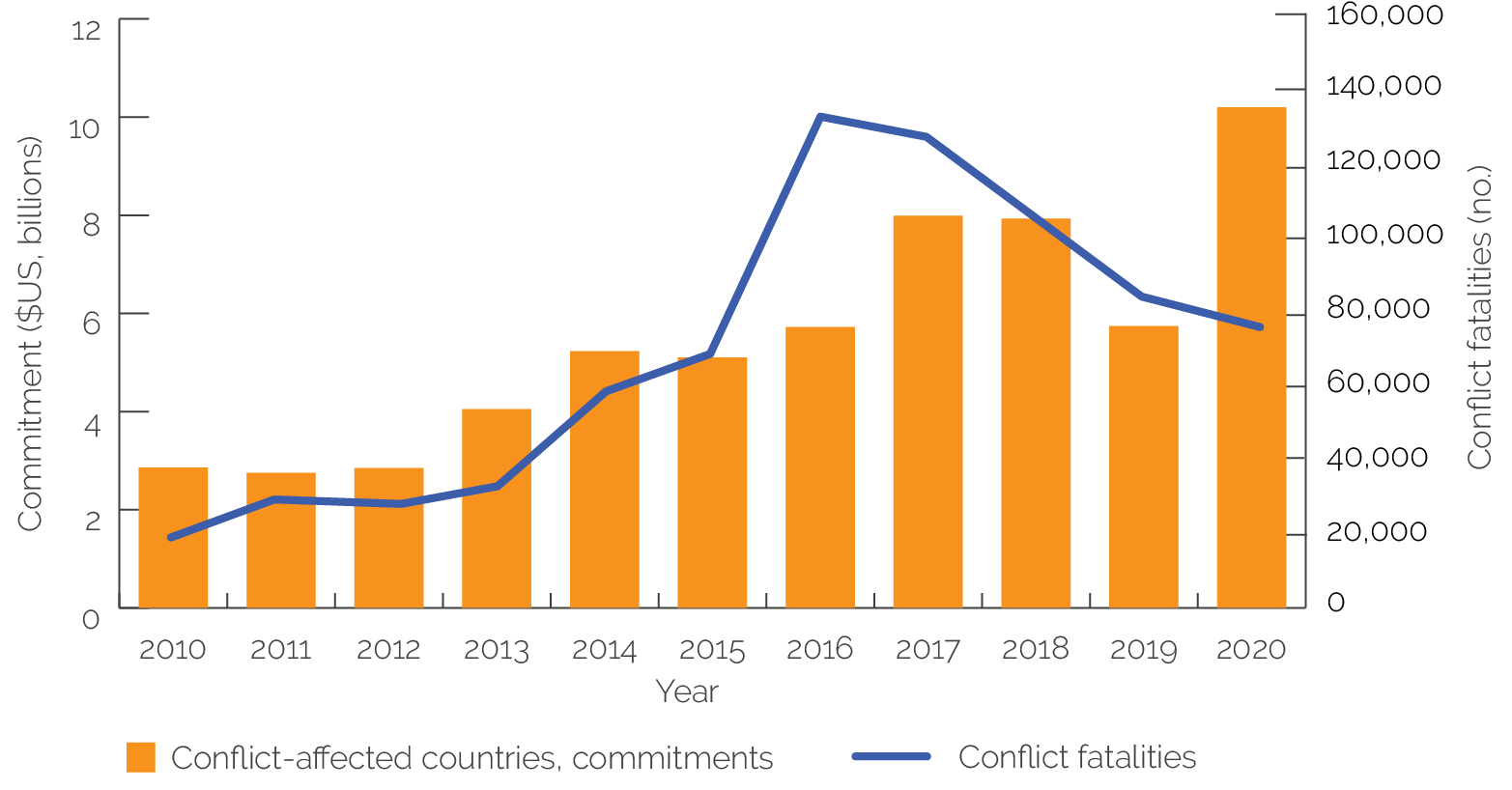

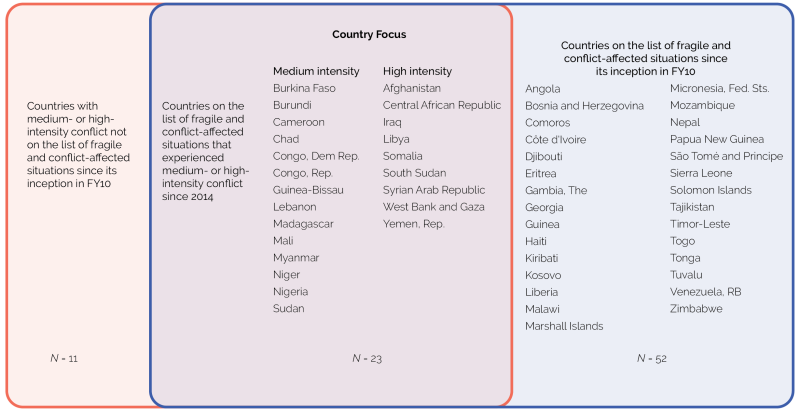

The purpose of this evaluation is to assess how the World Bank engages in situations of conflict to surface lessons that can inform the implementation of the FCV strategy. It does not evaluate the strategy itself. The evaluation was designed to analyze how the World Bank is working differently in conflict-affected situations. It focuses on a set of countries that have experienced conflict since 2014 and that are included on the World Bank’s FCS list (figure 1.2).3 Countries experiencing medium- to high-intensity conflict, but that were never on the list (N = 11) fall outside the evaluation scope. Appendix A details the methodology for determining this group, used to evaluate the World Bank’s engagement in situations of conflict.

Figure 1.2. The Focus of This Evaluation: Countries on the Harmonized List with Medium- or High-Intensity Conflict since 2014

Sources: World Bank Harmonized List of Fragile Situations (FY10–20); Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (database), https://acleddata.com; Uppsala Conflict Data Program (database), Uppsala University, https://www.pcr.uu.se/research/ucdp; World Bank 2020f (for definition of conflict intensity).

Note: Although West Bank and Gaza is a territory, not a country, members of the evaluation universe (N = 23) are referred to as countries for the sake of simplicity. FY = fiscal year.

Evaluation Limitations

The evaluation is limited in scope to the World Bank’s engagement during FY10–20 in countries on the FCS list with moderate to high levels of conflict since 2014. It does not cover broader issues related to fragility, including lessons on how clients can transition out of fragility; it also does not cover interpersonal violence. It does not cover the International Financial Corporation and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency interventions, since these are being covered in a parallel Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) evaluation. Issues of gender were not centrally addressed in this report, since IEG is preparing an evaluation on closing gender gaps in countries affected by FCV, which covers women’s economic opportunities and gender-based violence (GBV).

Evaluation Portfolio

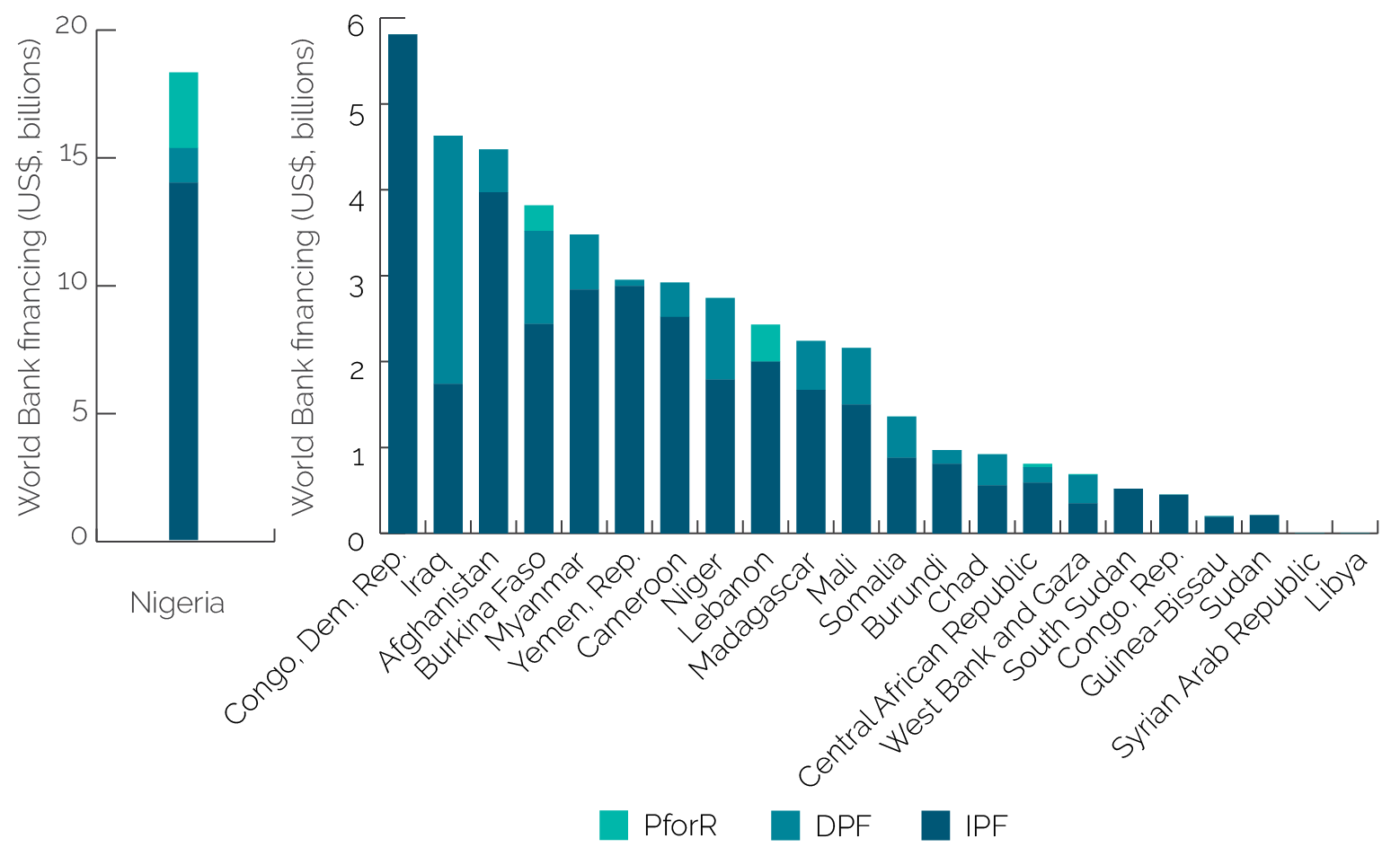

The World Bank approved 921 lending projects in countries on the FCS list with medium- or high-intensity conflict after 2014, comprising $58.3 billion in commitments during FY10–20. The portfolio consists of $44.8 billion in IDA commitments (77 percent), $8.5 billion in International Bank for Reconstruction and Development commitments (15 percent), and $5 billion in trust-funded commitments (9 percent). Investment project financing (IPF) projects accounted for 90 percent of financing engagements, amounting to approximately three-quarters of total volume. There were 88 individual development policy financing (DPF) operations (10 percent of the total number of projects),4 comprising $10.6 billion in commitments. Ten operations were Program-for-Results, for a total commitment of $3.7 billion. A quarter of all financing was received by Nigeria, and half was received by four countries (figure 1.3).

Between FY10 and FY20, the share of new commitments to the universe of conflict-affected countries has increased steadily both in nominal terms and as a share of all new commitments. The annual share of commitments to these countries as a percentage of all new World Bank commitments rose from 5 percent in FY10 to an annual average of 15 percent during FY15–20. Similarly, during FY10–20, conflict-affected IDA-eligible countries’ share of new commitments more than doubled (figure 1.4).

Figure 1.3. Total Commitments to Focus Countries, FY10–20

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: DPF = development policy financing; FY = fiscal year; IPF = investment project financing; PforR = Program-for-Results.

Figure 1.4. Commitments to Conflict-Affected Countries, Three-Year Average, FY10–20

Source: Independent Evaluation Group

Note: Commitments include all World Bank financing (IDA, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and trust funds). FY = fiscal year; IDA = International Development Association.

Given the heightened difficulties of maintaining development gains while battling COVID-19 in areas beset by conflict, the World Bank has approved a significant number of projects with COVID-19–relevant components in conflict-affected countries. As of the end of November 2020, the World Bank had approved 72 COVID-19 response projects to conflict-affected countries, valued at $7.3 billion.

The key question addressed by this evaluation is “How relevant and effective has World Bank engagement in situations of conflict been to the achievement of development gains?” To answer this question, the evaluation posed four subquestions:

- How well has the World Bank identified, managed, and mitigated conflict-related risks?

- How relevant and adaptive has World Bank engagement in situations of conflict been in terms of sequencing, prioritization, and instrument choice?

- How strategically and effectively has the World Bank worked with state actors, nonstate actors, and development partners in pursuit of its development objectives?

- What outcomes has the World Bank contributed to in situations of conflict?

Methods and Report Structure

To answer these questions, methods were designed to derive lessons for strategy and operations from the World Bank’s engagement in conflict-affected countries. These methods included a review of conflict risk analyses (fragility assessments, Risk and Resilience Assessments [RRAs], political economy analyses, and country social assessments), Systematic Country Diagnostics, and country strategies (Interim Strategy Notes, Country Engagement Notes, Country Assistance Strategies, and Country Partnership Frameworks [CPFs]); case analyses of 23 country situations; analyses of 186 investment operations implemented in conflict-affected countries as determined by a spatial-temporal analysis and 55 development policy operations (DPOs); a systematic analysis of country results frameworks, program documents, Implementation Completion and Results Reports (ICRs), and Implementation Completion and Results Report Reviews (ICRRs) to assess results and outcomes; and a review of conflict literature with a focus on metrics. These methods were informed by stakeholder engagement, including through more than 200 semistructured interviews with World Bank management, staff, and clients, and a survey of Corporate Security staff (appendix A).

The report is structured as six chapters. Chapter 2 assesses the extent to which the World Bank identified and addressed conflict-related drivers and risks at the strategy and country levels. Chapter 3 analyzes the extent to which the World Bank identified and addressed conflict-related drivers and risks at the operational levels and how the World Bank is managing and mitigating conflict risks at the strategic and operational levels. Chapter 4 presents the ways in which the World Bank has adapted its engagement to work differently in conflict-affected countries. Chapter 5 analyzes the extent to which World Bank engagements have contributed to all project-level results and higher-level outcomes related to peace and stability. Chapter 6 offers conclusions and presents recommendations to the World Bank to inform the implementation of the new FCV strategy.

- During fiscal years 2011–20, countries were placed on the harmonized list of fragile and conflict-affected situations if they either or both (i) were International Development Association (IDA)–eligible and scored 3.2 or less on the Harmonized Country Performance and Institutional Assessment index and (ii) had a United Nations mission or a regional peacekeeping or peace-building mission in the past three years (regardless of IDA eligibility). This typology had its detractors: Some argued that even if a given country is fragile by any reasonable definition, its status as a fragile state does not axiomatically map onto coherent theories of change, strategies, or instruments that international or domestic actors can deploy (Milante and Woolcock 2017). The 2020 fragility, conflict, and violence strategy addressed this concern by introducing a new methodology, identifying countries with high levels of institutional and social fragility as distinct from countries affected by violent conflict (World Bank 2020f). The decision to distinguish between countries suffering from institutional and social fragility and those that also experience violent conflict has set the World Bank on a path to better identifying and applying a customized set of tools, in line with prevailing realities and institutional capabilities.

- Also of relevance is paragraph 12 of the World Bank’s Investment Project Financing Policy, “Projects in Situations of Urgent Need of Assistance or Capacity Constraints,” based on its experience during political transitions, in situations in which there is no central government, and with alternative implementation arrangements (World Bank 2018f).

- This includes West Bank and Gaza, which is a territory.

- The Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) reviews programmatic development policy operation (DPO) series as a single entity, regardless of the number of operations in the series, given the same rating for each operation. For the purposes of this evaluation, however, the text refers to the number of individual operations (that is, DPOs in a programmatic series).