World Bank Support for Public Financial and Debt Management in IDA-Eligible Countries

Chapter 6 | Public Debt Management Capacity to Foster Debt Sustainability

This chapter analyzes the World Bank’s evolving support for PDM to IDA-eligible recipients.1 The focus is on lending and ASA support of debt management; not all World Bank–supported interventions (for example, peer-to-peer learning activities, activities under the Government Debt and Risk Management Program) are considered. Given significant developments in the debt profiles of IDA-eligible countries in recent years, the assessment extends the evaluation period beyond FY17 when possible.

History and Evolution of the World Bank’s Approach

The World Bank extensively supported PDM capacity building in IDA-eligible countries, many of which have benefited from major multilateral and bilateral debt relief initiatives. To date, 36 countries have received debt relief either through the HIPC Initiative or the MDRI (see appendix B for the list). Box 6.1 provides a description of the HIPC Initiative–MDRI, which reduced unsustainable public debt burdens through debt service relief and debt stock reductions. As part of this effort, the World Bank and its development partners ramped up efforts to equip beneficiaries of debt relief and other lower-income countries with the capacity and training to keep debt burdens at manageable levels, mainly through the DMF, a multidonor trust fund (box 6.2).

Box 6.1. Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative–Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative

The Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative–Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) aimed to reduce the external debt burdens of the poorest countries to create fiscal space and allow for the expansion of “pro-poor” spending and improved service delivery for the poor. The HIPC Initiative, which was launched in 1996 by the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, was supplemented in 2005 by the MDRI. This allowed for 100 percent relief on eligible debts by three multilateral institutions—the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the African Development Fund (the concessional window of the African Development Bank)—for countries that completed the HIPC process. In 2007, the Inter-American Development Bank decided to provide additional debt relief (“Beyond HIPC”) to Bolivia, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, and Nicaragua.

The HIPC Initiative was implemented in two stages: a decision point (when interim relief on debt service was obtained) and a completion point (when a reduction in the debt stock was obtained). Of the 39 eligible countries, 36 reached completion points and received HIPC debt relief of $76.9 billion, including $34.1 billion from multilateral creditors and $42.7 million from bilateral and commercial creditors (although participation from commercial creditors was partial). MDRI relief amounted to $42.4 million.

Source: International Monetary Fund and World Bank 2018b.

Box 6.2. Debt Management Facility Multidonor Trust Fund

The Debt Management Facility (DMF) is a multidonor trust fund established by the World Bank to help countries strengthen public debt management (PDM). Since 2008, it has been the main vehicle for providing nonlending support to 84 DMF-eligible countries (of the evaluation’s universe of 85, neither Fiji nor Syrian Arab Republic are DMF eligible; the West Bank and Gaza is DMF eligible but is not International Development Association (IDA) eligible and is therefore not a part of the evaluation’s universe). When the DMF was established, all DMF-eligible countries were eligible to borrow only from IDA (appendix B has a complete list of DMF-eligible countries).

The modalities of World Bank support for strengthening PDM under the DMF umbrella have evolved over time. During phase I of the DMF, from 2008 to 2013, client countries were offered three core debt management advisory and analytic products: Debt Management Performance Assessments, Medium-Term Debt Management Strategies, and debt management reform plans. In 2014, as the financing landscape of IDA-eligible countries started changing and more countries started issuing domestic and international bonds, the DMF expanded its program, which marked the beginning of Phase II (2014–18). Starting with Phase II, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund joined efforts to rationalize fundraising and draw on complementarities in support of PDM provided by the two institutions. This phase was characterized by new products: domestic debt market development, risk management, contingent liabilities, issuance of guarantees, access to international capital markets, and low-income country Debt Sustainability Framework analysis. The collaboration continues into Phase III of the DMF, launched in April 2019, with the objective to reduce debt-related vulnerabilities and improve debt transparency. DMF III is focused on delivering customized advice on sovereign debt management through the application of analytical tools, trainings, webinars, and peer-to-peer learning. In June 2019, the DMF expanded its program further to include support for debt reporting and monitoring, debt transparency, contingent liability, and fiscal risks. The DMF also finances training and peer learning networks for debt managers.

DMF II (2014–2018) was funded by eight donor governments and international financial institutions: the African Development Bank; the European Commission; and the governments of Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, the Russian Federation, and Switzerland. (For DMF III, which started in 2019, donors exclude the government of Russia and include the governments of Japan, France, the United Kingdom, and the United States). The delivery of the DMF work program is conducted in close collaboration with six implementing partners.

Source: Source: Debt Management Facility (https://www.dmfacility.org).

Two independent external evaluations of DMF performance, undertaken in 2013 and 2018, found that the DMF has been relevant to the debt management capacity-building needs of DMF-eligible countries and effective in supporting capacity building (Universalia 2013, 2018). According to the 2018 evaluation, DMF-supported activities were very relevant and highly valued for the quality of the expertise mobilized. They were most effective in developing and disseminating debt management capacity-development products, which have supported eligible countries in the take-up of new debt management methodologies and the creation of new debt management institutional structures. The DMF achieved progress in helping countries prepare and approve their own MTDSs and debt sustainability analyses, and there was evidence that these improvements had been sustained in the countries reviewed by Universalia. The DMF was less effective in helping countries develop and implement debt management reform plans, develop debt markets, access international capital markets, or prepare portfolio risk assessments. The evaluation made several recommendations about coordination between upstream and downstream country support, the introduction of a client country readiness assessment, and the need for increased coordination at the country level between debt management and public financial management providers, including in World Bank country offices.

Support for Public Debt Management Capacity Building

Improving PDM capacity in IDA-eligible countries was an important element of the 19th Replenishment of IDA (box 6.3). Attention to PDM in Replenishment discussions was motivated by a sense that “rising debt vulnerabilities in IDA countries could jeopardize their development goals at a critical time to meet the 2030 Development Agenda” (IDA 2019, i). Among the outcomes of the Replenishment discussions was an agreement to improve monitoring of debt vulnerabilities, enhance early warning systems, improve debt transparency, and increase debt management capacity building. This was part of the joint IMF–World Bank Track Record of IFMIS Support to IDA-Eligible Countries MPA (Multipronged Approach for Addressing Debt Vulnerabilities), which, among other things, sought to “strengthen capacity on debt/fiscal risk management to help countries deal with existing debt more effectively, including through operational support to strengthen macrofiscal policy frameworks and manage fiscal risks” (IDA 2019, 9).2

Box 6.3. Selected PFDM-Related IDA19 Policy Commitments

The 19th Replenishment of International Development Association (IDA19) recognized that “the composition of public debt, especially external public debt, has shifted toward costlier and riskier sources of finance. This shift reflects, in part, these countries’ increasing access to international markets and to bilateral financing from new external creditors” (IDA 2020a, 19). In response, IDA established several public financial and debt management–related commitments. Public debt management–specific actions are focused primarily on countries at moderate or high risk of debt distress to prevent a further deterioration in their debt burdens. The actions include the following:

- Supporting at least 25 countries through lending and nonlending to implement an integrated and programmatic approach to enhance debt transparency through increased coverage of public debt in debt sustainability analyses or supporting debt transparency reforms, or both, including requirements for debt reporting to increase transparency.

- Supporting at least 25 IDA-eligible countries to bolster fiscal risk assessments and debt management capacity through a scale-up of fiscal risk monitoring, implementation of debt management strategies, or both.

- Supporting at least 20 countries to identify the governance constraints on the development, financing, and delivery of quality infrastructure investments—with particular attention to project preparation, procurement, environmental and social considerations, and integrity—to inform the adoption of policies or regulations for enhanced infrastructure governance. (This public investment management commitment was designed to draw on a suite of instruments, including lending operations, diagnostics, and technical assistance.)

- Supporting at least 12 IDA countries to adopt universally accessible GovTech solutions (which include hardware, software, applications, and other technology to improve access and quality of public services, facilitate citizen engagement, and improve core government operations).

Source: IDA 2020a.

Note: PFDM = public financial and debt management.

Most World Bank efforts to strengthen PDM in IDA-eligible countries have been delivered through nonlending technical assistance. An important part of this assistance has been financed by the DMF, which supports the delivery of technical assistance, tailored advisory support, training, and peer-to-peer learning for DMF-eligible countries. The core technical assistance instruments used to support improvements in PDM are DeMPAs, MTDSs, and debt management reform plans. As of FY15, and driven by client demand, support has been provided for domestic debt market development, implementation of debt management strategies (for example, on annual borrowing plans), and cash management. Under the DMF in FY20, additional technical assistance is also being provided on debt transparency, including debt reporting, and on the management of contingent liabilities (including through credit risk assessment and guarantee frameworks).

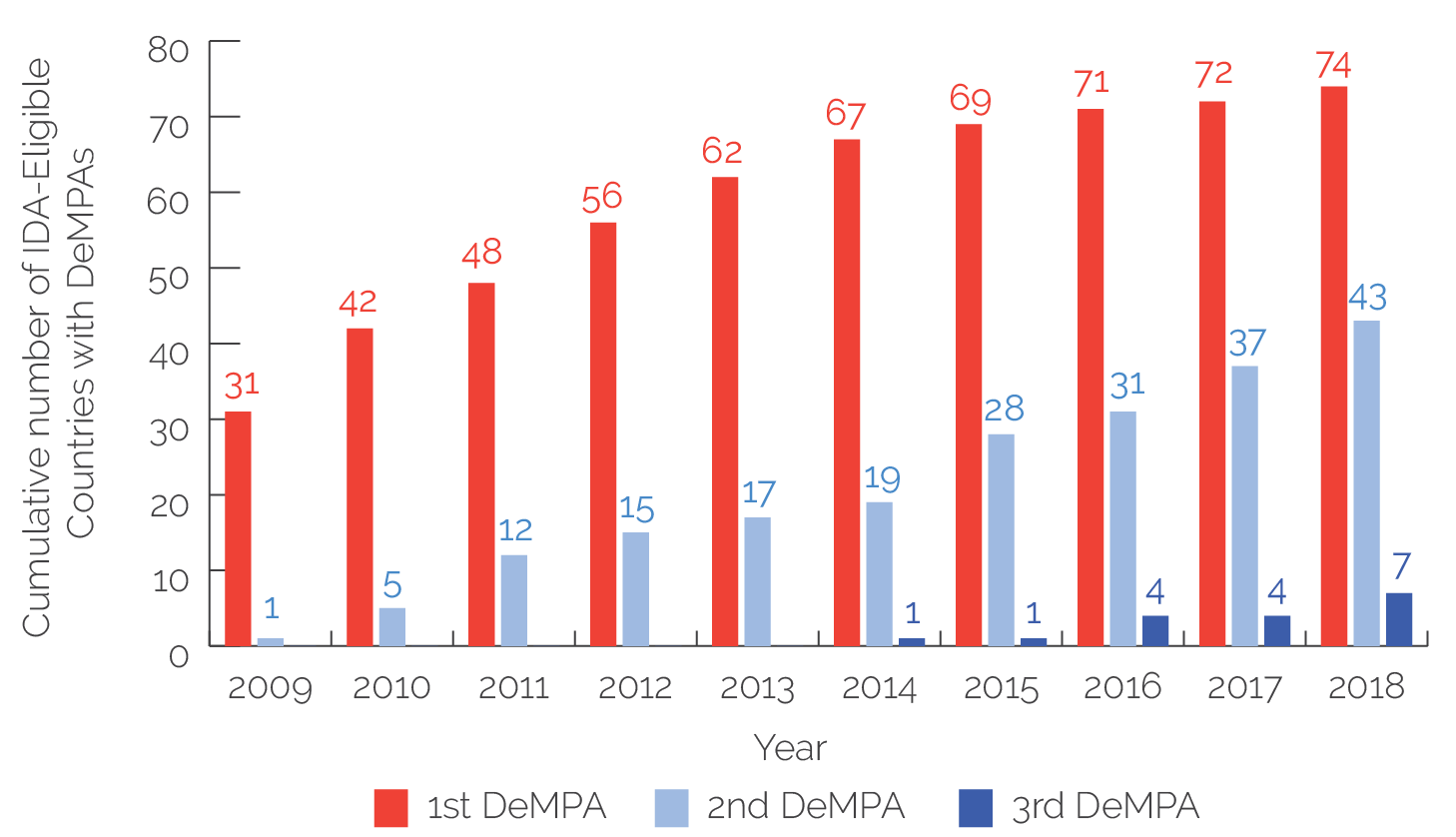

The foundation of World Bank support to improve debt management capacity is the World Bank’s DeMPA. As of the end of 2018, over 87 percent of IDA-eligible countries had received debt management diagnostic support in the form of a DeMPA, and almost 60 percent of those had had more than one DeMPA (figure 6.1). As IDA-eligible countries completed a DeMPA, interest in developing debt management reform plans to address identified shortcomings grew significantly. About three-quarters of countries that have had a DeMPA have subsequently articulated a debt management reform plan with DMF support.

To encourage initial participation in a DeMPA, results were treated as confidential and required country permission to publish, although the World Bank is now actively encouraging disclosure. To build support from donors and development partners, many countries have subsequently allowed their DeMPAs to be published. Slightly less than half of IDA-eligible countries with DeMPAs have publicly disclosed them online (table 6.1). Of these countries, 11 (44 percent) are currently either at high risk of debt distress or already in distress.3 In response to recent increases in the number of IDA-eligible countries that are at higher levels of debt distress, and to strengthen transparency in debt management, the World Bank has begun to more actively encourage countries to publish their DeMPA reports, although this recommendation has stopped short of a requirement to publish or a presumption of publication. Country authorization is still required for DeMPA publication.

Figure 6.1. IDA-Eligible Countries with DeMPAs

Source: Debt Management Facility Secretariat.

Note: N = 84. DeMPA = Debt Management Performance Assessment; IDA = International Development Association.

Table 6.1. IDA-Eligible Countries with Published DeMPAs

|

Year |

Countries with DeMPAs |

Countries with Published DeMPAs |

|

|

(no.) |

(no.) |

(percent) |

|

|

2009 |

31 |

13 |

42 |

|

2010 |

42 |

16 |

38 |

|

2011 |

48 |

21 |

44 |

|

2012 |

56 |

25 |

45 |

|

2013 |

62 |

29 |

47 |

|

2014 |

67 |

30 |

45 |

|

2015 |

69 |

33 |

48 |

|

2016 |

71 |

34 |

48 |

|

2017 |

72 |

34 |

47 |

|

2018 |

74 |

35 |

47 |

Source: Debt Management Facility Secretariat.

Note: Thirty-five IDA-eligible countries were found to have published DeMPAs; of those 35, 15 had two published DeMPAs. All numbers are cumulative. DeMPA = Debt Management Performance Assessment; IDA = International Development Association.

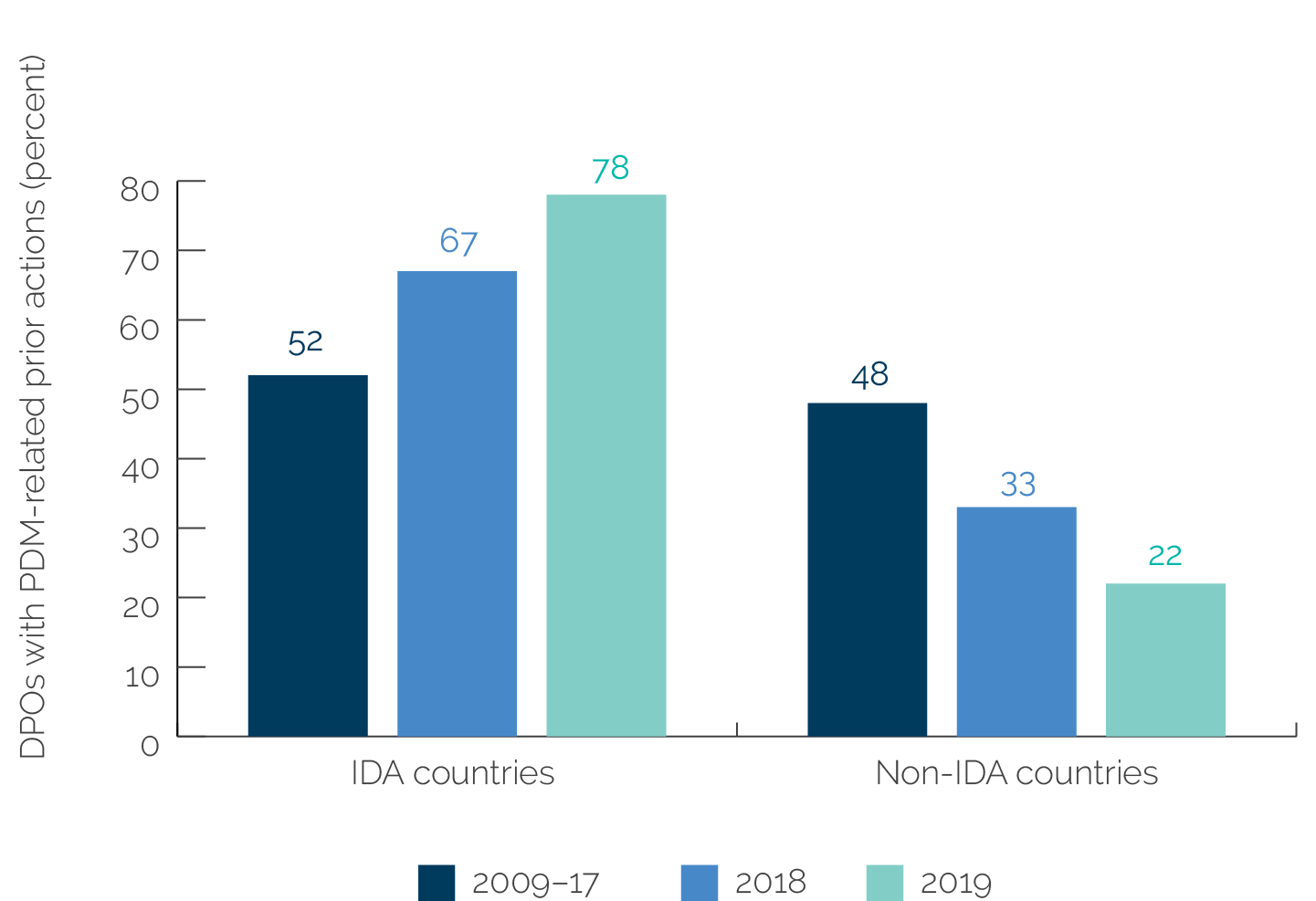

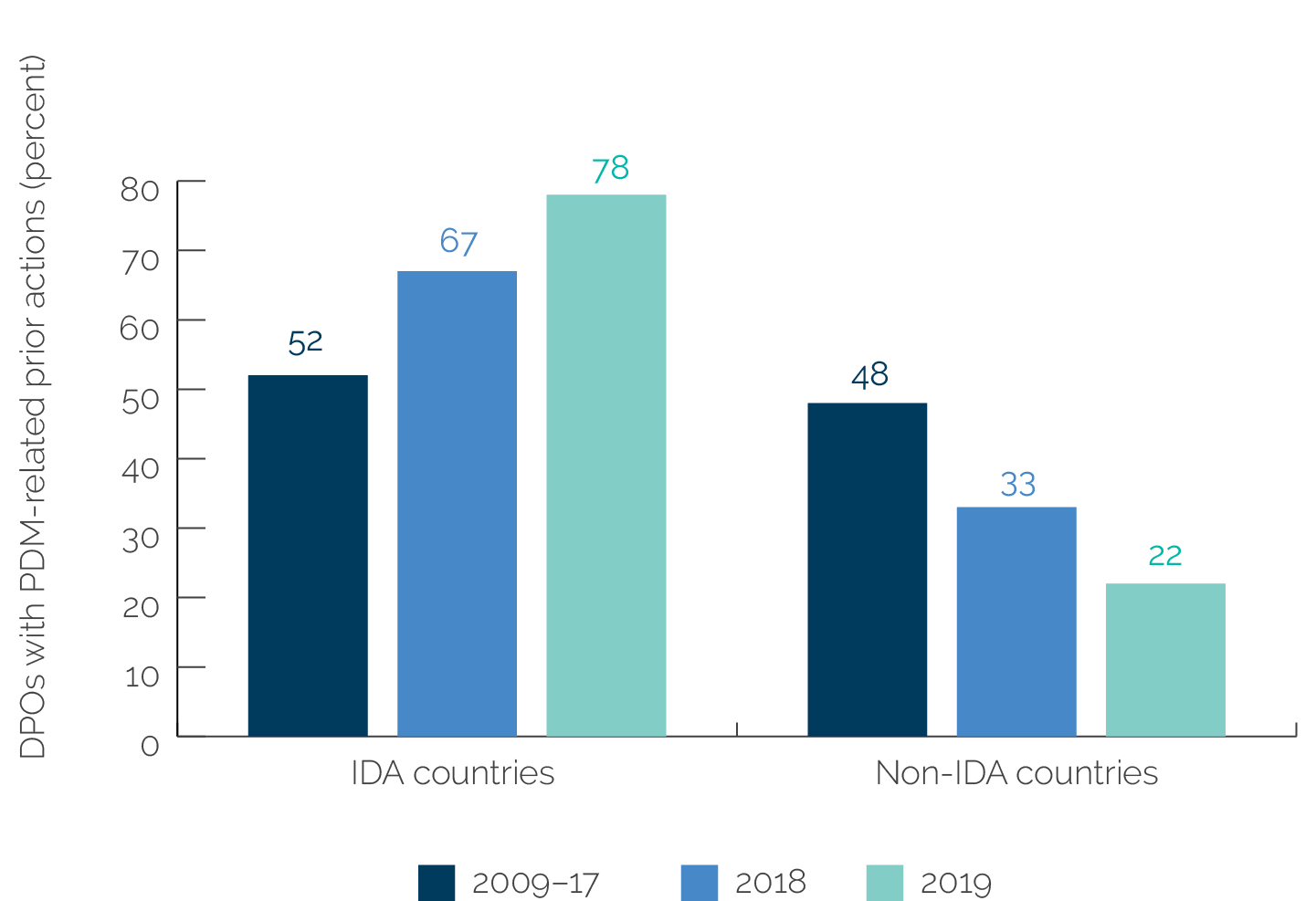

The World Bank has also used lending to support IDA-eligible countries to improve PDM. DPOs were the key lending instruments used to support PDM reform, as only 11 investment projects had activities focused on PDM.4 The number of DPOs with PDM-related prior actions increased significantly in 2018 and 2019 compared with the evaluation period (FY08–17). There has also been a sharp rise in the share of DPOs for IDA-eligible countries with at least one PDM-related prior action. At the same time, the use of PDM-related prior actions has been declining in DPOs for IBRD countries (figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2. Increased Share of DPOs with PDM-Related Prior Actions

Source: Independent Evaluation Group, Operations Policy and Country Services Prior Action Database.

Note: DPO = development policy operation; IDA = International Development Association; PDM = public debt management.

As the economic and financing landscape of IDA-eligible countries has evolved, the World Bank has adapted the form and scope of its PDM support. IEG noted that the World Bank has responded positively to increased demand for support for managing contingent liabilities, domestic market development, access to international markets, debt and fiscal sustainability analysis, and debt transparency (figure 6.3).

Figure 6.3. Debt Management Advisory Services and Analytics Products

Source: Debt Management Facility: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/debt/brief/debt-management-facility.

Note: ASA = advisory services and analytics; DeMPA = Debt Management Performance Assessment; MTDS = Medium-Term Debt Management Strategy.

In parallel, the World Bank and IMF have simplified PDM tools and prepared more user-friendly versions to enhance the relevance of the tools to lower-capacity recipients of DMF support.5 One example is the simplified version of the MTDS tool, which was made available to clients in 2014. Additionally, the DeMPA tool is currently being revised to provide more granularity in assessment and to improve its ability to measure progress at lower levels of capacity. This will be of particular benefit to countries—including several small or fragile states—that struggle to meet minimum debt management standards. Another example is the 2016 update of the Subnational DeMPA tool, which is used to assess PDM performance at the local government level.

The World Bank is increasingly providing PDM support in programmatic form. As seen in ongoing support to countries like Angola, Kenya, and Zambia, a programmatic approach can not only shorten the time between missions to increase continuity and improve effectiveness but also facilitate efforts to address PDM weaknesses in sequence, which can then improve collaboration among government counterparts.

Many of the countries that received support through a programmatic debt management reform plan have implemented PDM reforms. By the end of 2018, almost two-thirds of DMF-eligible countries had been provided with technical support through a debt management reform plan to adopt debt legislation; strengthen managerial structures; establish a debt management function; or enhance debt transparency through the preparation and publication of a debt management strategy, public debt bulletins, or debt statistics reports. Thirty percent of that subset of countries requested a follow-up reform plan.

According to feedback from national authorities, the significant training provided by the World Bank to government officials on various aspects of debt management has been seen as effective. MTDS support focused on building country capacity to independently prepare loan portfolio cost and risk analyses, to identify an appropriate borrowing strategy, and to produce a debt management strategy with the intent to publish it. The World Bank provided significant training to government officials on the use of the MTDS methodology and tool, but granular data on participation (that is, participating countries by region, year, number of trained participants, and so on) are not publicly available before FY18, when data started to be published in DMF annual reports. However, earlier surveys of national authorities note that most countries that had received MTDS technical assistance indicated that it helped them improve the quality of their debt management strategies, including by introducing a structured and coherent approach to designing a debt management strategy and raising awareness of risks among senior officials and broader stakeholders (World Bank and IMF 2017). By the end of the evaluation period, approximately 60 percent of DMF-eligible countries had received MTDS support, and roughly half of these had prepared a debt management strategy and published it on a government website. The number of strategies published by IDA-eligible countries increased from 3 in 2010 to 35 in 2018, although an assessment of debt management strategy quality has not yet been undertaken (Development Committee 2018).

On July 1, 2018, the new low-income country Debt Sustainability Framework became effective, with training on the improved tool beginning in 2017. The DMF organized extensive outreach activities to promote the low-income country Debt Sustainability Framework, including 18 workshops for 380 total participants in FY18 (compared with 8 workshops in FY17) with a focus on conducting a debt sustainability analysis. From July 2018 to December 2019, 14 regional trainings were provided to 277 participants. A country’s ability to conduct its own debt sustainability analysis is tracked by DeMPAs; however, training on the new tool only began in mid-2018, and the infrequency with which DeMPAs are undertaken means it is too soon to assess the tool’s impact. That said, preliminary findings suggest that capacity development is generating improvements.

Effectiveness of Public Debt Management Support

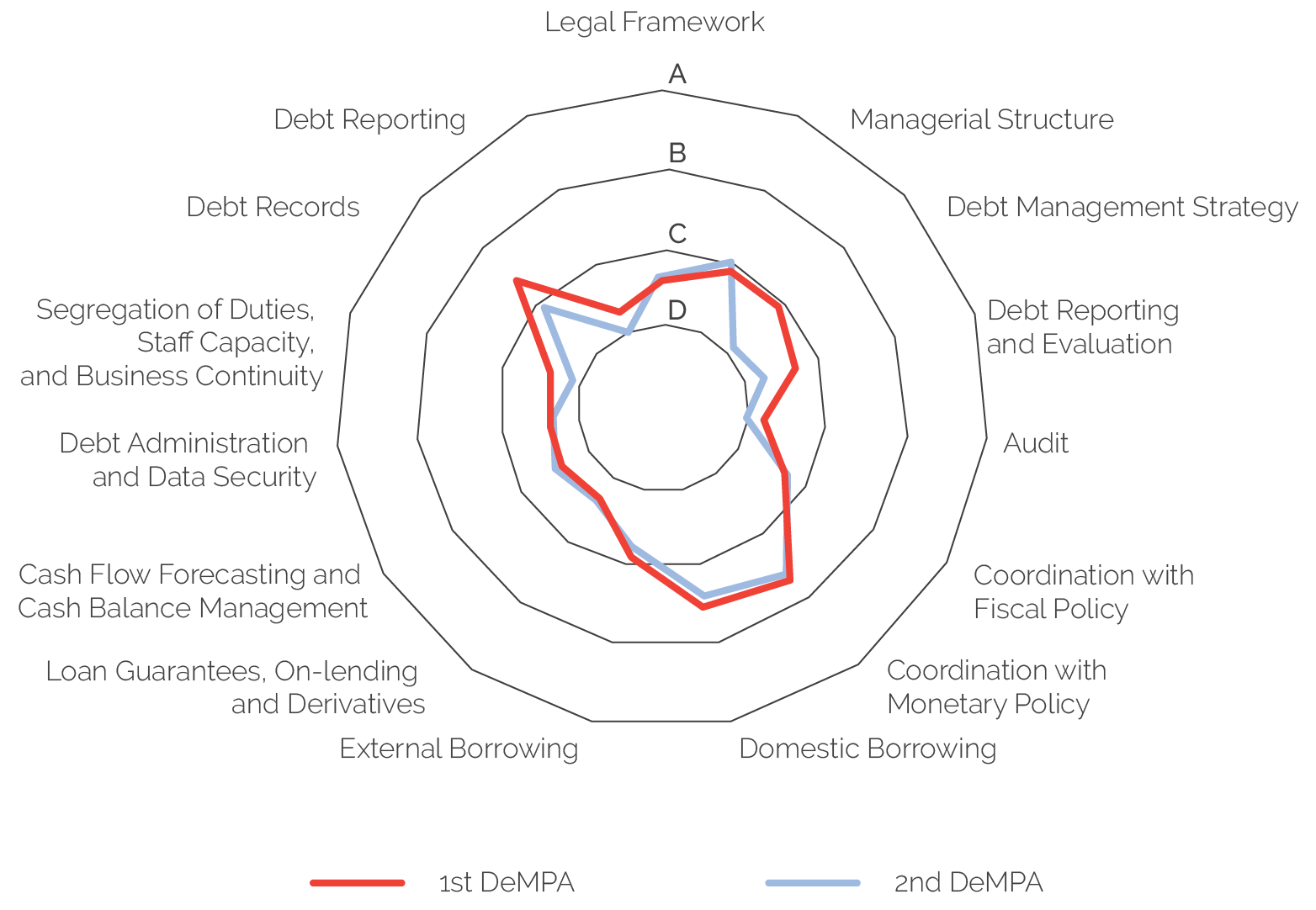

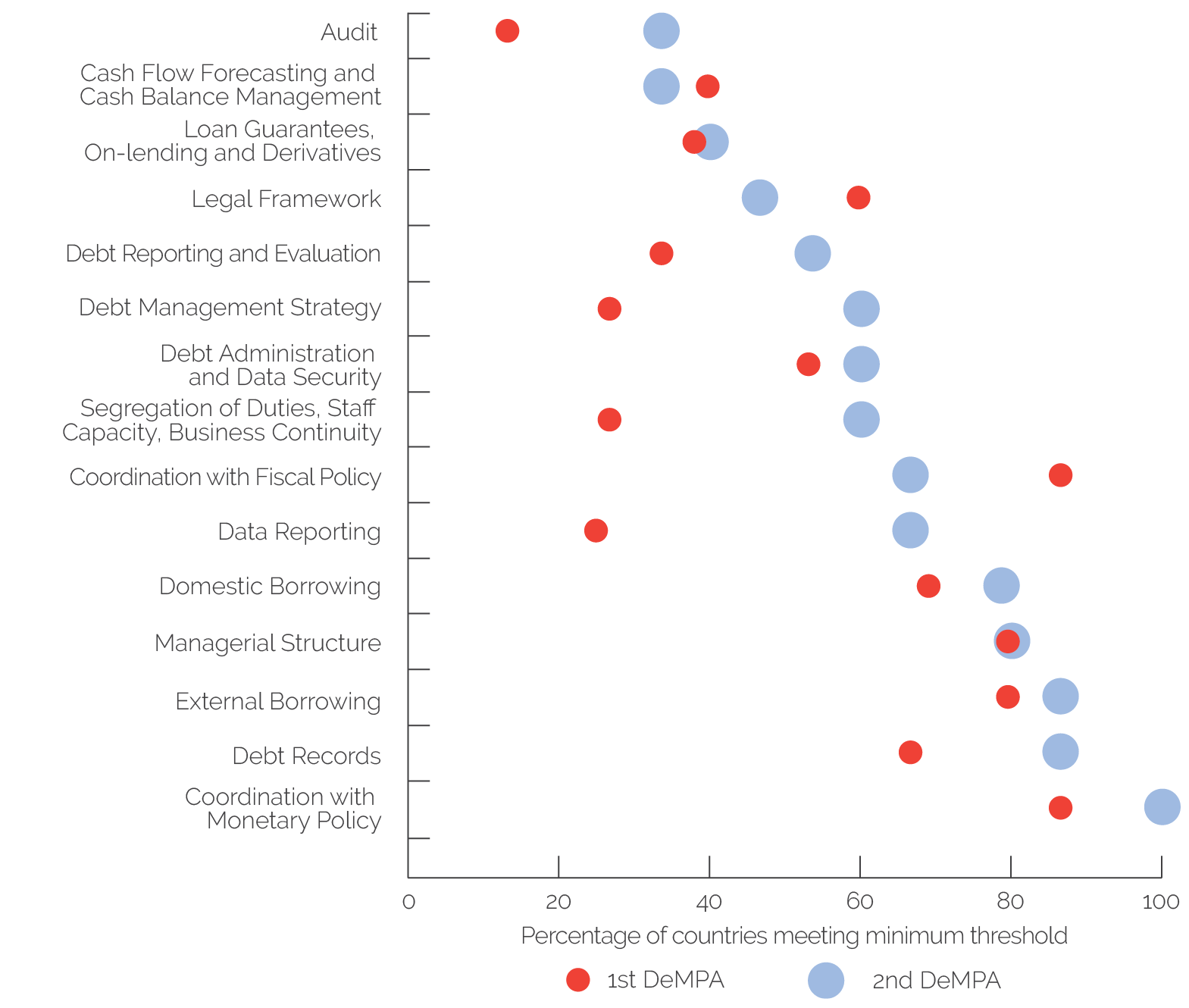

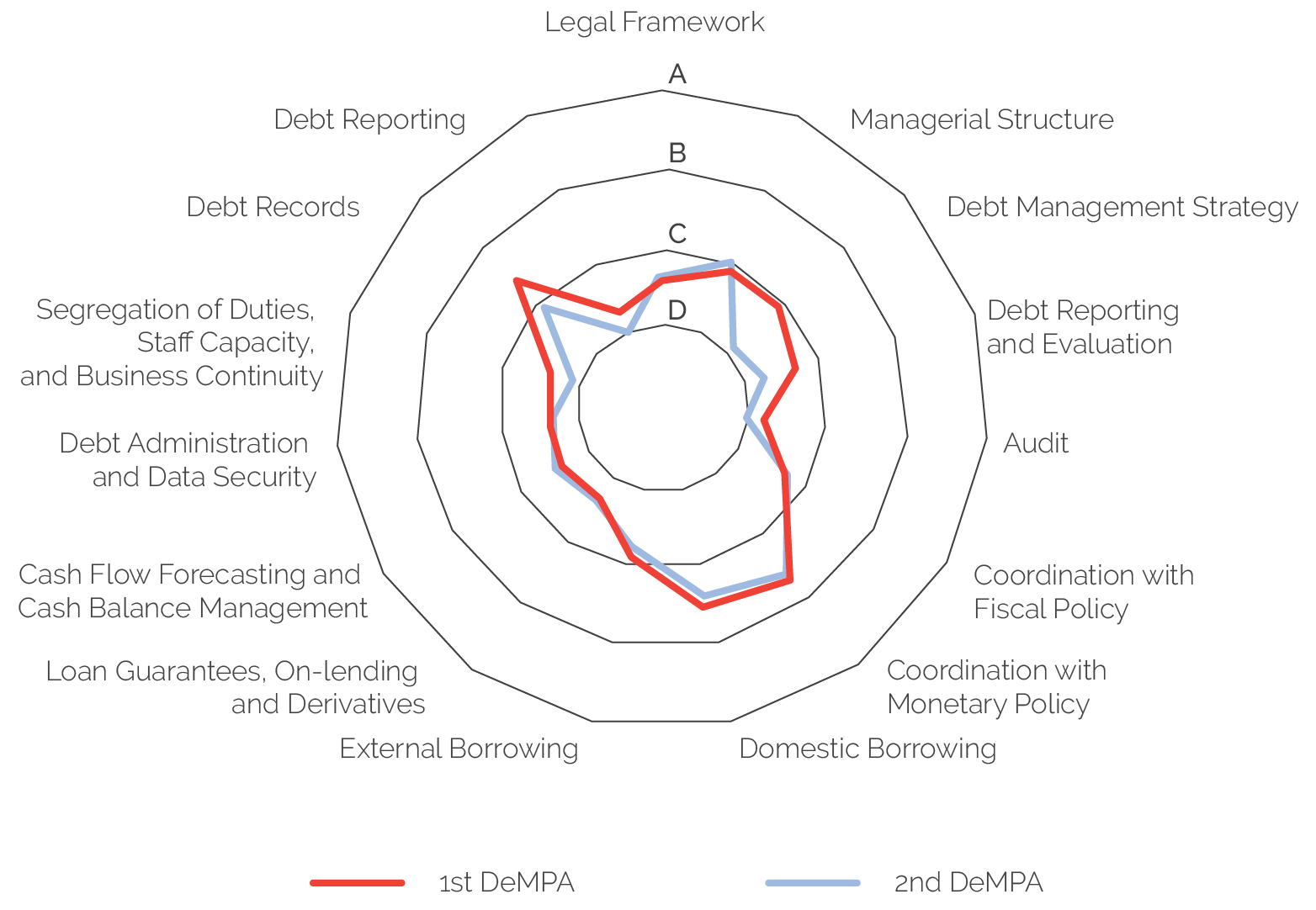

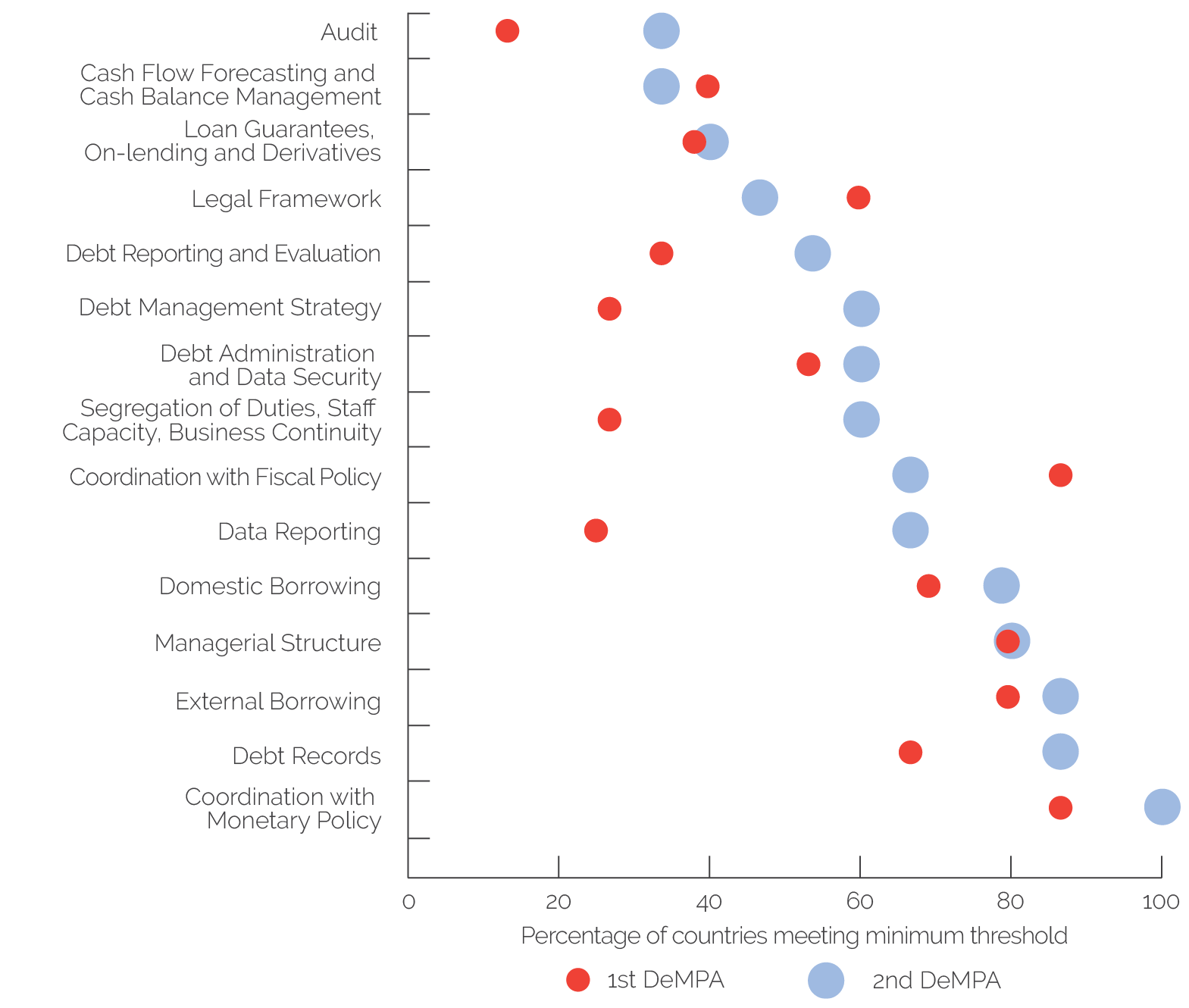

Publicly available evidence suggests that, after 10 years of DMF support, there have been improvements in debt management among recipient countries. In the 15 IDA-eligible countries that have at least two published DeMPAs,6 there were modest but positive changes in 10 of the 15 debt performance indicators (figure 6.4); modest declines were noted in (i) legal framework; (ii) managerial structure; (iii) coordination with fiscal policy; (iv) loan guarantees, on-lending, and derivatives; and (v) cash flow forecasting and cash balance management.7 Additionally, the percentage of countries meeting the minimum thresholds for the 15 debt performance indicators increased between the first and second DeMPAs: More than 50 percent of the countries achieved the minimum threshold for 8 debt performance indicators during their first DeMPA; in the second DeMPA, more than 50 percent of the countries achieved the minimum threshold for 11 debt performance indicators (figure 6.5).

Figure 6.4. Change in DeMPA Scores for IDA-Eligible Countries with At Least Two Publicly Disclosed DeMPAs

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: N = 30 (15 IDA-eligible countries were found with at least two publicly disclosed DeMPAs: Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Cambodia, The Gambia, Guinea, Kosovo, Maldives, Mali, Moldova, Mozambique, Papua New Guinea, Senegal, Togo, Uganda, and Zimbabwe). DeMPA = Debt Management Performance Assessment; IDA = International Development Association.

Modest improvements in DeMPA scores can also be observed at the regional level. Overall average DeMPA scores for Africa and for East Asia and Pacific stagnated over the evaluation period. However, more granular analysis reveals improvements in several debt performance indicators of improved managerial structure, domestic borrowing, debt recording, reporting, and evaluation. More than half the observed countries in the Africa Region met the minimum score requirements in 11 out of 15 indicators on their second DeMPA, up from 8 on their first. Appendix H includes country comparisons from cases with more than one DeMPA during the evaluation period.

Figure 6.5. Share of IDA-Eligible Countries Meeting Minimum Threshold (First versus Second DeMPA)

Source: Independent Evaluation Group, Debt Management Performance Assessment data.

Note: N = 30 (15 IDA-eligible countries were found with at least two publicly disclosed DeMPAs: Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Cambodia, The Gambia, Guinea, Kosovo, Maldives, Mali, Moldova, Mozambique, Papua New Guinea, Senegal, Togo, Uganda, and Zimbabwe). DeMPA = Debt Management Performance Assessment; IDA = International Development Association.

- As mentioned earlier, this report only covers support to International Development Association–eligible countries; as such, it does not evaluate support or customized technical advisory services on debt management to middle-income countries through the Government Debt and Risk Management Program.

- The multipronged approach is composed of four pillars: (i) strengthening debt transparency by helping borrowing countries, and by reaching out to creditors, to make better public sector debt data available; (ii) supporting capacity development in public debt management to avert and mitigate debt vulnerabilities; (iii) providing suitable tools to analyze debt developments and risks; and (iv) exploring adaptations to the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) and World Bank’s lending policies to better address debt risks and promote efficient resolution of debt crises (World Bank and IMF 2020, 2).

- Debt Management Facility: https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/debt-toolkit/dempa..

- Investment project financing went to the Democratic Republic of Congo, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, India, Kenya, the Kyrgyz Republic, Mongolia, and Nigeria; Programs-for-Results went to India and Uganda.

- The World Bank and IMF are collaborating more broadly on improving debt management and debt transparency (IMF and World Bank 2018a, 2018b; World Bank and IMF 2020).

- Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Cambodia, The Gambia, Guinea, Kosovo, Maldives, Mali, Moldova, Mozambique, Papua New Guinea, Senegal, Togo, Uganda, and Zimbabwe.

- World Bank and IMF (2017) confirm the negative change over time for cash flow forecasting and cash balance management; however, additional findings are aggregated to category rather than indicator, complicating a confirmation with their figures.

- This study found a wide range of systems supported by integrated financial management information systems: some focused only on treasury operations, others on broader financial management information systems, including medium-term budgetary frameworks, medium-term expenditure frameworks, performance-based budgeting, human resources, debt, public investment, payroll, tax, and customs. The average cost for the operational systems in the sample was $6.6 million, but there was high variability depending on scale and scope. World Bank operations supporting these systems tended to disburse slower than planned. See also Combaz (2015).

- These were (i) Liberia—First Poverty Reduction Support Credit (PRSC-1), which stated, “The Recipient, through its MOF [Ministry of Finance], has adopted [an] IFMIS [information financial management information system] in payroll processing, with a view to strengthening fiscal discipline and budget transparency,” and (ii) Tanzania—Open Government and Public Financial Management, which stated, “The Recipient’s MoF [Ministry of Finance] has issued instructions to spending units to commit all expenditures through the IFMIS [information financial management information system]; and the Recipient’s appropriated budget for FY [fiscal year] 14/15 has provided funding to reduce the level of expenditure arrears.”

- As mentioned earlier, this report only covers support to International Development Association–eligible countries; as such, it does not evaluate support or customized technical advisory services on debt management to middle-income countries through the Government Debt and Risk Management Program.

- The multipronged approach is composed of four pillars: (i) strengthening debt transparency by helping borrowing countries, and by reaching out to creditors, to make better public sector debt data available; (ii) supporting capacity development in public debt management to avert and mitigate debt vulnerabilities; (iii) providing suitable tools to analyze debt developments and risks; and (iv) exploring adaptations to the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) and World Bank’s lending policies to better address debt risks and promote efficient resolution of debt crises (World Bank and IMF 2020, 2).

- Debt Management Facility: https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/debt-toolkit/dempa..

- Investment project financing went to the Democratic Republic of Congo, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, India, Kenya, the Kyrgyz Republic, Mongolia, and Nigeria; Programs-for-Results went to India and Uganda.

- The World Bank and IMF are collaborating more broadly on improving debt management and debt transparency (IMF and World Bank 2018a, 2018b; World Bank and IMF 2020).