World Bank Support for Public Financial and Debt Management in IDA-Eligible Countries

Chapter 5 | Supporting Integrated Financial Management Information Systems to Increase Budgetary Discipline

This chapter analyzes the relationship between IFMIS and PFDM performance. It details World Bank support during the evaluation period to IDA-eligible countries for IFMIS implementation, rollout, and expansion in coverage. Drawing on existing analytical work, it highlights the contribution to fiscal discipline that IFMISs can make, as well as shortcomings in support for IFMISs that undermines their value added.

Building IFMIS capacity has been associated with improvements in PFDM outcomes. IFMISs enable finance officials to plan, prepare, and approve budgets; approve and verify commitments; issue payment orders and payments; monitor and report on financial resources collected; and develop appropriate resource allocation and borrowing strategies. Properly functioning IFMISs lay the basis for transparency and accountability of budget management, fundamental prerequisites for strong PFDM, by ensuring that countries’ spending priorities are funded as planned, deficits do not exceed projections, and critical services are not compromised by an unexpected lack of resources. Piatti-Fünfkirchen, Hashim, and Wescott (2017) found a positive (but weak) association between IFMIS coverage and the PEFA PI-1 score (which captures aggregate expenditure outturns in relation to budgeted amounts).

The World Bank was the leading multilateral supporter of IFMIS over the evaluation period. During the evaluation period, just over 60 percent of IDA-eligible countries (52 of 85) received lending support to develop or expand their IFMIS through 90 investment project financings and two Programs-for-Results. For a comprehensive analysis of World Bank support to 87 IFMIS projects in 51 countries (both IDA and IBRD eligible) during 1984–2010, see Dener, Watkins, and Dorotinsky (2011).1 In 2018, IEG conducted a review of evidence from World Bank support to IFMIS implementation and published the lessons learned: It is the foundation on which this evaluation is built (Hashim and Piatti-Fünfkirchen 2018).

Owing in part to positive earlier results in middle-income countries, the World Bank expanded its support for IFMIS to lower-income countries over the evaluation period. IEG assessed projects approved and completed (or both) during the evaluation period and found 48 supporting IFMIS in IDA-eligible countries (compared with 18 projects approved and completed from 1982 to 2007). This expansion was particularly pronounced in lower-income countries: The regional focus of the World Bank’s support was Africa (about half of projects), with a roughly equal share in each of East Asia and Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, and South Asia.

Track Record of IFMIS Support to IDA-Eligible Countries

IFMIS project success rates over the evaluation period have not matched earlier success rates. For those projects in IDA-eligible countries completed and rated by IEG during the evaluation period, less than 47 percent were rated moderately satisfactory or better. This is below the performance of IEG-rated projects in IDA-eligible countries over the previous 25 years, of which 62.5 percent were rated moderately satisfactory or better (table 5.1). This difference is likely at least partially a function of the expansion of support to lower-capacity, lower income IDA-eligible countries. Lower rates might also be a function of moving from support for the establishment and rollout of IFMISs to support for improved coverage and usage of a system (a more complex endeavor).

Table 5.1. Outcome of IDA-Eligible IFMIS Projects: FY08–17 versus Previous 25 Years (percent)

|

Rating |

Prior Period |

Evaluation Period |

|

Highly satisfactory |

0 |

0 |

|

Satisfactory |

12.5 |

13.3 |

|

Moderately satisfactory |

50.0 |

33.3 |

|

Moderately unsatisfactory |

20.8 |

13.3 |

|

Unsatisfactory |

16.7 |

33.3 |

|

Highly unsatisfactory |

0 |

6.7 |

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

|

Moderately satisfactory or better |

62.5 |

46.7 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Prior period was defined as FY1982–2007. FY = fiscal year; IDA = International Development Association; IFMIS = integrated financial management information system.

A slightly lower proportion of IFMISs were fully operational during the evaluation period compared with beforehand, largely owing to the lower capacity of countries receiving IFMIS support. Survey data from 74 projects providing IFMIS support to IDA-eligible countries (for projects approved or closed, or both, during the evaluation period) show an increase in the proportion of projects either with systems operating with reduced scope or not implemented at all (table 5.2). A review of Implementation Status and Results Reports of the 22 projects from the evaluation period that have not yet closed suggests that a lower rate of implementation is likely. This is problematic, as IFMISs with limited coverage—the total volume processed through the IFMIS divided by total approved budget—do not provide the budget management benefits necessary to support fiscal discipline (Hashim and Piatti-Fünfkirchen 2016; Hashim et al. 2019).

Table 5.2. Operational Status of IFMIS Projects: Evaluation Period (FY08–17) versus Previous 25 Years (percent)

|

Status |

Prior Period |

Evaluation Period |

|

System is fully or partially operational |

38 |

32 |

|

System is operational for pilot or reduced scope |

46 |

50 |

|

System was not implemented or is not operational |

17 |

18 |

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Forty-eight International Development Association–eligible projects were assessed for the earlier period and 44 for the evaluation period (projects that were ongoing during the analysis were excluded). The prior period was FY1982–2007. FY = fiscal year; IFMIS = integrated financial management information system.

IFMIS Coverage and Fiscal Discipline

Broad IFMIS coverage and use is necessary to control arrears and maintain fiscal discipline. When high-value transactions—transfers, wage bills, subsidies, capital expenditure, and debt payments—are processed through the system (and thus subject to automated, ex ante internal controls), the accumulation of arrears is avoided. Piatti-Fünfkirchen, Hashim, and Wescott (2017) found a negative relationship between IFMIS coverage and deviations between actual and budgeted fiscal balances. When all transactions are processed through the system, spending units are prevented from incurring commitments they are unable to pay.

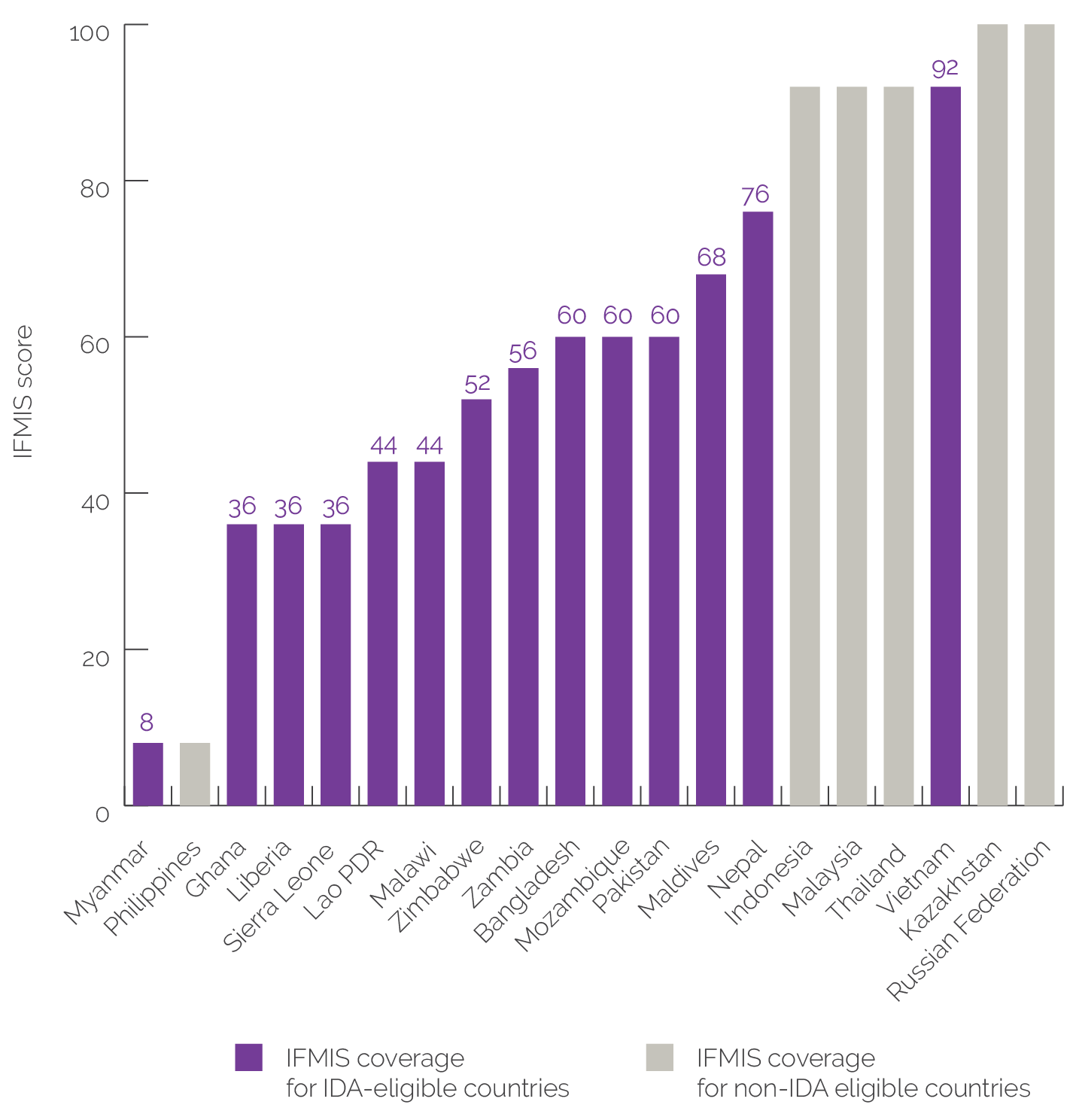

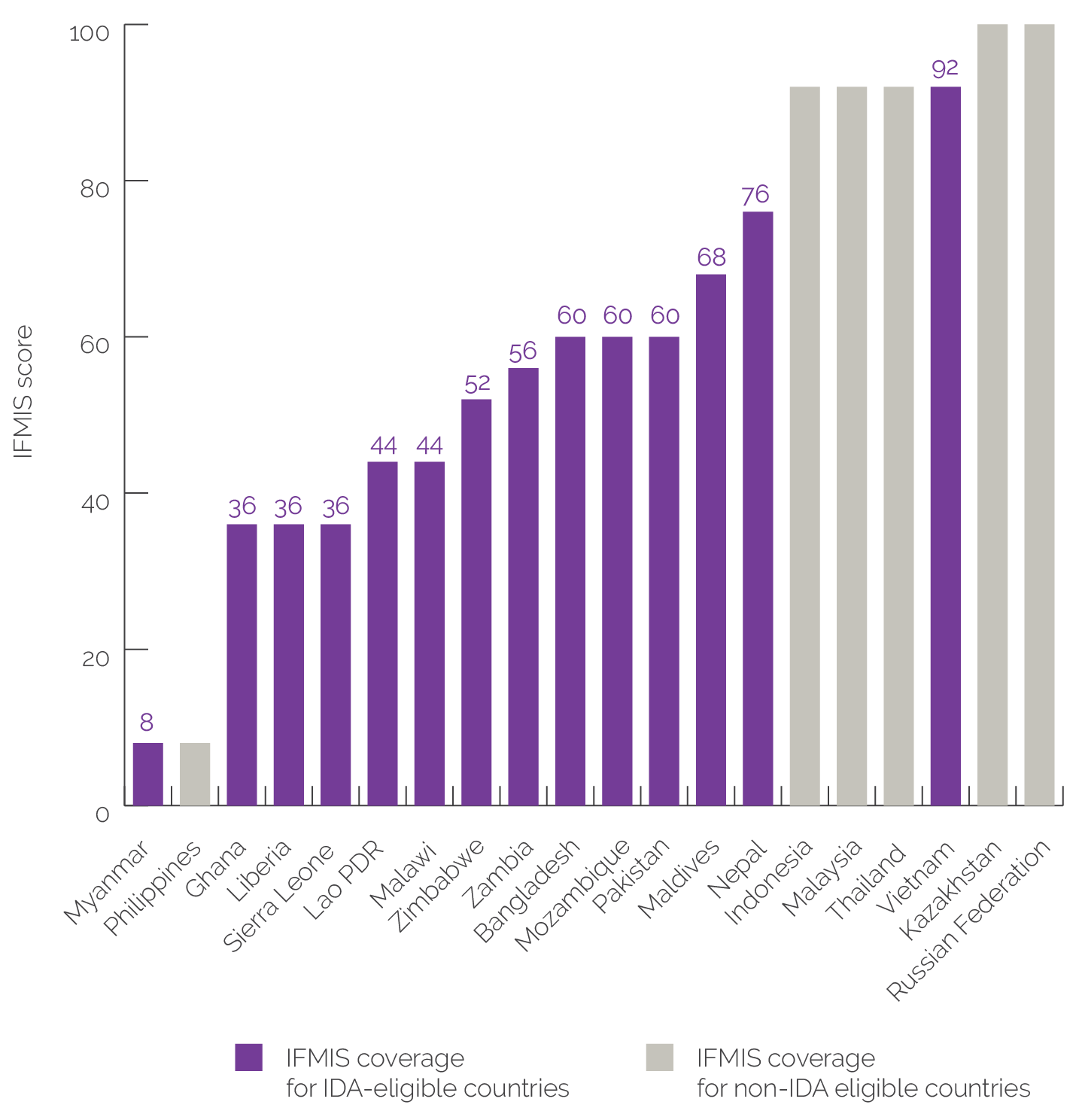

World Bank support to IFMIS capacity building has not paid sufficient attention to ensuring that high-value transactions are channeled through the system. An assessment of IFMIS coverage points to limited progress among IDA-eligible countries (figure 5.1). Prominent among these are Ghana, Liberia, Malawi, Sierra Leone, and Zambia, where costly IFMIS projects were implemented over long periods of time. The deficiency in coverage cannot be explained by the underlying technology platforms and technical capacity of the systems: The core functionality of the systems that determines their capacity for budget execution and control is complete, and the technology platform used is state-of-the-art and identical to that used in several middle-income countries (such as Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, and the Russian Federation, which show high budget coverage). In these countries, although sophisticated systems are in place, only a small percentage of the transactions related to government financial resources are being channeled through them and are subject to the ex ante controls necessary for good fiscal management.

Figure 5.1. Comparison of IFMIS Coverage Score by Country, 2016

Source: Adapted from Hashim and Piatti-Fünfkirchen 2016.

Note: International Development Association–eligible countries in purple; International Bank for Reconstruction and Development borrowers’ countries in gray. Scores have been transformed to a 0–100 scale for simplicity. IFMIS = integrated financial management information system.

World Bank support to ensure that transactions were reliably and comprehensively processed in IFMIS was found to be lacking at times. An effective IFMIS requires that all budgetary transactions are routed through the system and subject to system controls. World Bank support to IDA-eligible countries did not always give due attention to the importance of this requirement (box 5.1). The quality of information available from the financial operations and management reporting layers will depend on the quality, timeliness, and comprehensiveness of the transaction data captured by the transaction-processing layer. In many countries—for example, Ghana, Pakistan, and Zambia—the transaction-processing layer did not include large portions of government financial resources and was therefore not comprehensive, implying that financial operations and management reporting would not be based on complete data. This was found to undermine data integrity in the transaction-processing layer, which makes the functional and economic reports generated from the system questionable.

Box 5.1. Examples of World Bank Support for Integrated Financial Management Information Systems

- Vietnam’s Public Financial Management Reform Project (2003–13) successfully developed and operationalized a fully functioning integrated financial management information system (IFMIS) by prioritizing the coverage of core budget execution processes and the processing of payments and receipts. Thanks to such sequencing, a large part of Vietnam’s budget was covered by ex ante budget and cash controls early on in the IFMIS deployment, allowing for quick wins in the areas of meaningful fiscal control and cash management.

- Cambodia’s Public Financial Management Modernization Project (2013–17) supported the building of capacity to process payments and receipt transactions at treasury offices before rolling out other modules and going into other organizational units. Capacity development activities used in-house resources instead of external consultants to ensure sustainability and prepare for rollout. Thanks in large part to these actions, the IFMIS budget control and execution modules were successfully rolled out to the capital treasury and all 24 provincial treasuries, and the time needed to locate financial data, produce reports, process payments, and close financial accounts declined.

- The eGhana Project (2006–14) successfully rolled out an IFMIS for budget preparation, accounting, and reporting on most ministries, departments, and agencies. However, in-depth evaluation by the Independent Evaluation Group revealed that only transactions related to expenditures on goods and services, external debt servicing, capital expenditures, and other salary expenditures were being routed through the system. Transactions related to wages and salaries, domestic debt servicing, internal generated funds, statutory funds, extrabudgetary funds, and donor funds were not routed through the IFMIS before being paid (although data from the follow-on project, Ghana Public Financial Management Reform Project, fiscal years 2016–21, suggest that this issue has since been addressed).

- Malawi’s Financial Management, Transparency, and Accountability Project (2003–09) did not focus on ensuring regular enforcement of commitment controls, which was one factor that contributed to the embezzlement of approximately $32 million. Despite ongoing World Bank support for system development and rollout, spending units were able to continue generating local purchase orders and issuing checks and vouchers using proforma invoices. The processing of commitments outside the system led to the accumulation of large payment arrears, which were estimated at 9.2 percent of gross domestic product in 2014. This breakdown in the accountability chain paved the way for the so-called Cashgate Scandal.a

Source: World Bank 2016a, 2016d, 2016e, 2018c.

Note: a. The 2014 audit commissioned by the National Audit Office of Malawi after the scandal concluded: “During an unannounced ad hoc IT Security Audit …. our inspection of the firewall configuration indicated that the firewall settings had been changed to permit any outside connection. We also found that the password controls had been disabled, and the connections to the IFMIS servers, that should have been routed through the network firewall, had bypassed the firewall” (Baker Tilly 2014, 116).

World Bank use of DPO prior actions to increase IFMIS coverage has been rare. Of the 714 PFDM prior actions supported by DPOs in IDA-eligible countries, 625 were PFM related; of those, just 22 were IFMIS implementation related. Of those, only two specifically mention increased IFMIS coverage;2 the bulk focused on rolling out the solution to additional government entities (in other words, coverage) but not ensuring usage.

- This study found a wide range of systems supported by integrated financial management information systems: some focused only on treasury operations, others on broader financial management information systems, including medium-term budgetary frameworks, medium-term expenditure frameworks, performance-based budgeting, human resources, debt, public investment, payroll, tax, and customs. The average cost for the operational systems in the sample was $6.6 million, but there was high variability depending on scale and scope. World Bank operations supporting these systems tended to disburse slower than planned. See also Combaz (2015).

- These were (i) Liberia—First Poverty Reduction Support Credit (PRSC-1), which stated, “The Recipient, through its MOF [Ministry of Finance], has adopted [an] IFMIS [information financial management information system] in payroll processing, with a view to strengthening fiscal discipline and budget transparency,” and (ii) Tanzania—Open Government and Public Financial Management, which stated, “The Recipient’s MoF [Ministry of Finance] has issued instructions to spending units to commit all expenditures through the IFMIS [information financial management information system]; and the Recipient’s appropriated budget for FY [fiscal year] 14/15 has provided funding to reduce the level of expenditure arrears.”

- Only low-income countries are assessed by the debt sustainability analysis. The evaluation universe includes countries that were IDA-eligible for at least two years during the evaluation period; 14 countries are no longer low income. Additionally, Fiji recently became low income, so does not yet have a debt sustainability analysis assessment, and the Syrian Arab Republic has not been assessed for debt sustainability since its lending category became inactive.

- World Bank and IMF (2017) notes the complementarities between public investment management and public debt management. It explains that public investment management focuses on the need to ensure that all costs—including debt service costs—associated with investment projects are published.