The World Bank Group's Engagement in Morocco 2011-21

Chapter 5 | Enhancing Citizen Participation

Highlights

The World Bank has struggled to translate its thorough diagnostics of the barriers to citizens’ civic and economic participation into effective operations.

Responding to the 2011 events, the World Bank made helping the state promote civic and economic participation a pillar of its country strategies in Morocco and has produced high-quality diagnostics on barriers that prevent Moroccans from fully engaging in civic and economic life.

The World Bank’s operational use of its quality diagnostic work on low youth and female participation in the labor force has been fragmented.

The World Bank has had mixed success in improving the public’s access to data and institutionalizing citizen engagement mechanisms.

The World Bank’s insensitivity to political changes caused its efforts to improve citizen participation in the justice sector to fail.

The World Bank Group has recently started promising experiments with instruments to address financing and capacity issues at the subnational level.

The World Bank investment projects have started recently to ensure compliance with citizen engagement corporate guidelines on mainstreaming citizen engagement during the implementation of investment project financings.

This chapter assesses the Bank Group’s contributions to enhancing citizen participation in Morocco’s civic and economic life. The NDM identifies several barriers that limit citizen participation (which constitutes the fourth systemic obstacle to Morocco’s development). These barriers include few labor opportunities for youth and women; ineffective citizen engagement mechanisms, particularly in the justice sector; and the limited control of subnational territories over their own development (CSMD 2021). The chapter evaluates the Bank Group’s attempts at removing these barriers. The FY10–13 CPS was silent on citizen participation issues, but these issues were prominent in the country strategies that followed the 2011 Arab Spring and the World Bank’s 2015 Middle East and North Africa Regional strategy (Devarajan and Mottaghi 2015). The FY14–17 CPS made gender equality, youth inclusion, and citizen voice cross-cutting priorities. In turn, the FY19–24 CPF made job creation and youth employability its first focus area, retained women’s and girls’ empowerment as a cross-cutting theme, and made citizen-state engagement a “foundational” pillar. Overall, this chapter finds that the World Bank provided useful diagnostics, innovative digital solutions, and promising experiments in financing local development but struggled with enhancing women and youth participation in the labor force, promoting citizen participation in civic and economic life, and increasing subnational participation in the country’s development.

Enhancing Labor Force Participation

Bank Group country strategies made youth and gender issues a priority, but operational efforts to increase youth and female labor force participation have been timid and fragmented. The right to work is enshrined in Morocco’s constitution, yet Morocco’s use of its human capital is low and declining, especially for women and young people. In 2019, youth employment stood at 42 percent (HCP 2020), with more than 1.7 million youth ages 15–24 years (27 percent) classified as not in education, employment, or training. Women have higher rates of unemployment compared with men: 13.5 percent for women and 7.8 percent for men. In fact, in 2018, Morocco’s female labor force participation rate was just 21 percent, ranking Morocco 180 out of 189 countries.1 All three Bank Group country strategies—in 2010, 2014, and 2019—acknowledged the depth and urgency of youth and gender challenges by treating youth and gender as cross-cutting themes. Moreover, each strategy became progressively more ambitious on these issues, but the envisioned activities did not always materialize in the portfolio. The first strategy mentioned the need for analytical work on gender but did not have a concrete plan; the second strategy planned for comprehensive analytical work, including a gender assessment and gender-disaggregated data, and acknowledged a need for gender-specific lending but did not plan any operations; the third strategy planned for specific measures in existing lending operations but limited its focus to women’s financial inclusion. Despite this increasing ambition, the Bank Group’s response to low youth and female labor participation remained piecemeal, with mostly small activities scattered across the portfolio and no lending activities dedicated to gender labor issues.2 Contrary to other strategic areas, which combined analytics and policy dialogues to gain government traction, youth and gender labor issues had no coherent theory of change, nor did the Bank Group devise a programmatic approach underpinned by policy dialogues with Moroccan authorities.

The World Bank carried out comprehensive diagnostics on youth employability but struggled to act on them in policy financing. Throughout the decade covered by this evaluation, the Bank Group produced six high-quality diagnostic reports on labor force participation challenges, specifically those faced by Moroccan youth. Each report incorporated new data, evaluative evidence, and knowledge from other countries and arrived at coherent and consistent recommendations (table 5.1). However, unlike the Bank’s achievements in facilitating policy changes in human capital formation and protection (see box 5.1), it failed to trigger policy action on the issue of human capital use. Interview with task team leaders confirmed that most of these reports, except Morocco’s Job Landscape: Identifying Constraints to an Inclusive Labor Market (Lopez-Acevedo et al. 2021a), were not widely disseminated and did not inform policy decisions. For example, the World Bank’s 2008 job diagnostic report (known as the MILES report and 2012 youth inclusion study demonstrated that the most significant challenges were faced by low-skilled youth in lagging regions and that their needs were not being served by the government’s active labor market programs (World Bank 2008, 2012b). These active labor market programs targeted university graduates—who constitute only 5 percent of unemployed youth (Dadush 2018)—and predominantly benefited youth in the Casablanca-Tangier region. In dialogues for the 2012 and 2015 DPF series, Bank Group staff tried to broaden the DPF with measures to remove labor force participation barriers for unskilled youth. However, the DPF series ended up focusing on measures to curb unemployment among university graduates, which was the most salient issue for the government after the 2011 uprising. The only part of the DPF that focused on unskilled youth was a mandate to implement specific active labor market programs for hard-to-place unemployed workers and a trigger to expand services from the main employment agency, L’Agence Nationale de Promotion de l’Emploi et des Compétences, to nongraduates. As a result, some services were opened to low-skilled job seekers, but limited implementation capacity of L’Agence Nationale de Promotion de l’Emploi et des Compétences meant that these services often did not reach or meet the needs of youth, women, and job seekers with no formal education.

Table 5.1. Recommendations on Labor Force Participation from World Bank Diagnostics

|

Recommendations |

World Bank Diagnostics |

|

Improve skill match and quality of diplomas/specialization supplied by the higher education and vocational training system, especially for women, in emerging sectors of the economy (for example, the digital sector) and in sectors that could allow women to work from home. |

Lopez-Acevedo et al. 2021a; World Bank 2008 |

|

Improve cost-effectiveness of active labor market programs by combining technical training, life skills training, internships, and accreditation and by strengthening accountability of service providers. |

World Bank 2008, 2012b, 2014d |

|

Improve targeting and coverage to focus on disadvantaged youth and address the not in education, employment, or training problem. Ensure that L’Agence Nationale de Promotion de l’Emploi et des Compétences provides support to unskilled youth (nongraduates), especially in underserved regions, in a cost-effective manner. |

Lopez-Acevedo et al. 2021a; World Bank 2008, 2012b, 2014d |

|

Improve effectiveness of entrepreneurship programs. Ensure that youth entrepreneurship programs are well targeted to focus on less-educated youth and offer comprehensive support, including skills training, access to capital, and long-term mentoring. |

World Bank 2012b |

|

Improve cross-sectoral coordination of programs that target the same beneficiaries but are delivered by different ministries and strengthen the role of municipalities in local coordination of youth inclusion. |

World Bank 2008, 2012b, 2014d |

|

Increase labor market mobility and control labor costs through a reformed social security system. Improve bridges and certifications that would allow workers to go from one sector to another. |

Lopez-Acevedo et al. 2021a; World Bank 2008, 2014d |

|

Break down legal, economic, and social barriers to women’s employment and labor force participation. Address the limited implementation of existing legislation as a result of weak institutional capacity and selective enforcement by public officials influenced by social norms. Remove remaining barriers in women’s access to finance, ownership of family assets, and entrepreneurship. Design interventions to change attitudes toward women’s work. Improve provision of childcare services, especially in urban areas. |

Chauffour 2018; Lopez-Acevedo et al. 2021a; World Bank 2015b |

|

Encouraging formalization. Find policy measures that increase the benefits and lower the costs of informality. Improve the skills of workers in the informal sector and the productivity of microenterprises. |

Lopez-Acevedo et al. 2021a; World Bank 2008 |

Sources: Chauffour 2018; Lopez-Acevedo et al. 2021a; World Bank 2008, 2012b, 2014d, 2015b.

Note: The MILES framework investigates five sectors for binding constraints in job creation (World Bank 2008). Each letter of MILES stands for one of these sectors—Macroeconomic conditions, Investment climate and infrastructure, Labor market regulations and institutions, Education and skills development, and Social protection.

Until recently, the World Bank’s attempts at improving youth employment were small in scale and overly focused on self-entrepreneurship. The World Bank’s diagnostics and evaluations identified limitations to the government’s self-entrepreneurship approach to reducing youth unemployment. World Bank evaluations found the programs to be effective at helping self-entrepreneurs start a business, but noted that they struggled to reach beneficiaries, and reducing the program’s high dropout rate because of youth entrepreneurs’ limited access to finance. Despite these identified shortcomings, the World Bank still focused its operations primarily on youth self-entrepreneurship. All of these operations were small trust fund–financed grants; the largest was a $5 million microentrepreneurship operation for disadvantaged youth. These operations were innovative because they tried to connect youth with unexplored employment markets. However, the programs were limited in scale and focused on noncore employment channels, such as crafts, self-employment, and employment abroad. It was not until 2019 that the World Bank rolled out a large IPF ($55 million) that built off the recommendations from its diagnostic work.

The World Bank’s operational response to falling female labor force participation has been marginal. The World Bank studied the causes of Morocco’s low and declining rate of female labor force participation in the study of gender equality (World Bank 2015b), the CEM (Chauffour 2018), and the programmatic job landscape (Lopez-Acevedo et al. 2021a). However, some of these causes would take many years and extensive efforts to overcome, such as low growth in sectors that employ women or low cultural demand for urban female workers with university degrees. That said, the World Bank identified several legal and policy constraints that, if lifted, could produce immediate improvements in the rate of Morocco’s female labor force participation. These policy reforms include changing tax incentives, enhancing access to finance, developing affordable childcare services, enabling part-time formal employment, and ensuring that certain laws related to divorce, equity in hiring, and others are enforced. So far, the World Bank has not gained traction with the government to translate its recommendations into operational support for these reform areas other than a requirement that financial inclusion operations benefit women. Only two gender-specific operations have been prepared to date. IFC has delivered an advisory service for employers, which includes three sets of activities: (i) creating a nationwide peer-learning platform, with the Confédération Générale des Entreprises du Maroc, to increase the skills and awareness of participating firms; (ii) launching a social media campaign to encourage company leaders to make gender equality commitments; and (iii) helping two clients obtain Excellence in Design for Greater Efficiencies certification. For its part, the World Bank included in its Second Financial and Digital Inclusion budget support program prior action to set mandatory quotas for women on the boards of publicly traded companies, with a target of (at least) 30 percent female representation by 2024 and 40 percent by 2027. In interviews, several development partners said that they were disappointed in the Bank Group’s weak engagement on labor participation issues for youth and women, and gender equality more broadly.

Enhancing Civic Participation

The World Bank’s efforts to promote open data and digital solutions to improve the state-citizen interface are starting to yield results. As highlighted by the NDM and reports from the CESE (2019), the state and its citizens have an asymmetrical relationship. Citizens face red tape, high transaction costs, and sometimes corrupt practices when accessing basic administrative services. The national e-government strategy—launched in 2009 and supported by the World Bank’s DPL series on public administration—seeks to remedy some of these issues by using digital solutions to improve the efficiency, transparency, and accountability of service providers. Over the past decade, the World Bank has worked with the Higher Planning Commission (Haut Commissariat au Plan, the national statistical organization), the National Observatory for Human Development (Observatoire National du Développement Humain), and several line ministries to promote better access to data. Through technical assistance, the World Bank has produced data, notably on poverty and business, and enhanced data sharing across ministries (for example, by promoting the interoperability of registries and management of information systems). As a result, Morocco is doing well on data production and services, scoring 88.4 out of 100 on the World Bank’s 2019 Statistical Performance Indicators (which is higher than the averages in Middle East and North Africa and lower-middle-income countries). However, the World Bank still faces institutional resistance to improving public access to national census and survey data on households, agriculture, and the labor force. Morocco scored 0 out of 1 for administrative data openness on the Statistical Performance Indicators (World Bank 2019c). As several key informants put it, “data [are] power” in Morocco, and there are many institutional barriers to sharing those data.

The World Bank was successful at institutionalizing citizen feedback mechanisms when it supported both sides of the citizen-state interface. More specifically, these mechanisms were successful when they raised citizen awareness and built citizen trust in the mechanisms and when they built the capacity of the state’s service providers to properly address grievances. Successful interventions were also deliberately piloted and expanded. For example, the World Bank’s PforR with the Ministry of Health successfully established a grievance redress mechanism (GRM). To accomplish this, the World Bank first diagnosed challenges with the existing GRM, then pilot-tested an implementation manual that accounted for those challenges, raised citizen awareness of a regional hotline number for sharing grievances, and built the capacity of subnational providers to handle the grievances. The GRM was so successful that the World Bank provided additional financing to handle grievances related to the COVID-19 pandemic. The GRM’s functionality is now trusted by citizens and has led to improvements in health service delivery. However, citizen feedback mechanisms were less successful when citizen awareness and capacity building were lacking. This was the case for the e-petition system, supported by the World Bank’s Hakama DPL series and other operations, which allowed citizens and civil society organizations to contest parliamentary and government decisions. The e-petition system did not support both sides of the citizen-state interface and instead focused on building the system’s technical functionality. As a result, citizens’ awareness and trust in the mechanism remain weak, and the system is underused.

The World Bank’s attempts to improve citizen participation in the justice sector failed because the World Bank did not sufficiently adjust its approach to the country’s political changes. Starting in 2009, the World Bank carried out diagnostic work and technical assistance in the justice sector and, in 2011, produced a Justice Public Expenditure Review. To follow up on the review’s recommendations, in 2010, the World Bank was asked to finance a $16 million IPF operation to strengthen Morocco’s capacity to deliver justice services to citizens and businesses. The project sought to pilot a participatory reform process—involving judges, judicial staff, and justice users—in select courts and strengthen the capacity of the Ministry of Justice to support and monitor the courts. The project was under preparation when the 2011 protests swept across Morocco. The protests led to constitutional reforms, parliamentary elections, and subsequently a new ruling coalition. The new Minister of Justice drastically changed the ministry’s priorities and launched a national dialogue on justice sector reforms, which culminated in the National Charter for Judicial Reform in 2014. The project design was not adjusted to the changing political economy. As a result, the project’s implementation faced challenges from the beginning because of low government ownership and insufficient World Bank reactivity. Eventually, the national dialogue overshadowed the project and the government lost interest completely when the EU, with the United Nations Children’s Fund and the Council of Europe, committed €75.5 million to the ministry’s alternative program. The ministry increasingly lost faith in the ability of the World Bank–supported project to deliver on its priorities and agreed to cancel it in 2015. The project closed without delivering any of its outputs and was rated “highly unsatisfactory” at completion. After this experience, the World Bank did not engage with the government on further justice sector reforms but continued analytical work on the topic, notably through the CEM, which covered issues of rule of law and justice extensively.

Enhancing Subnational Participation

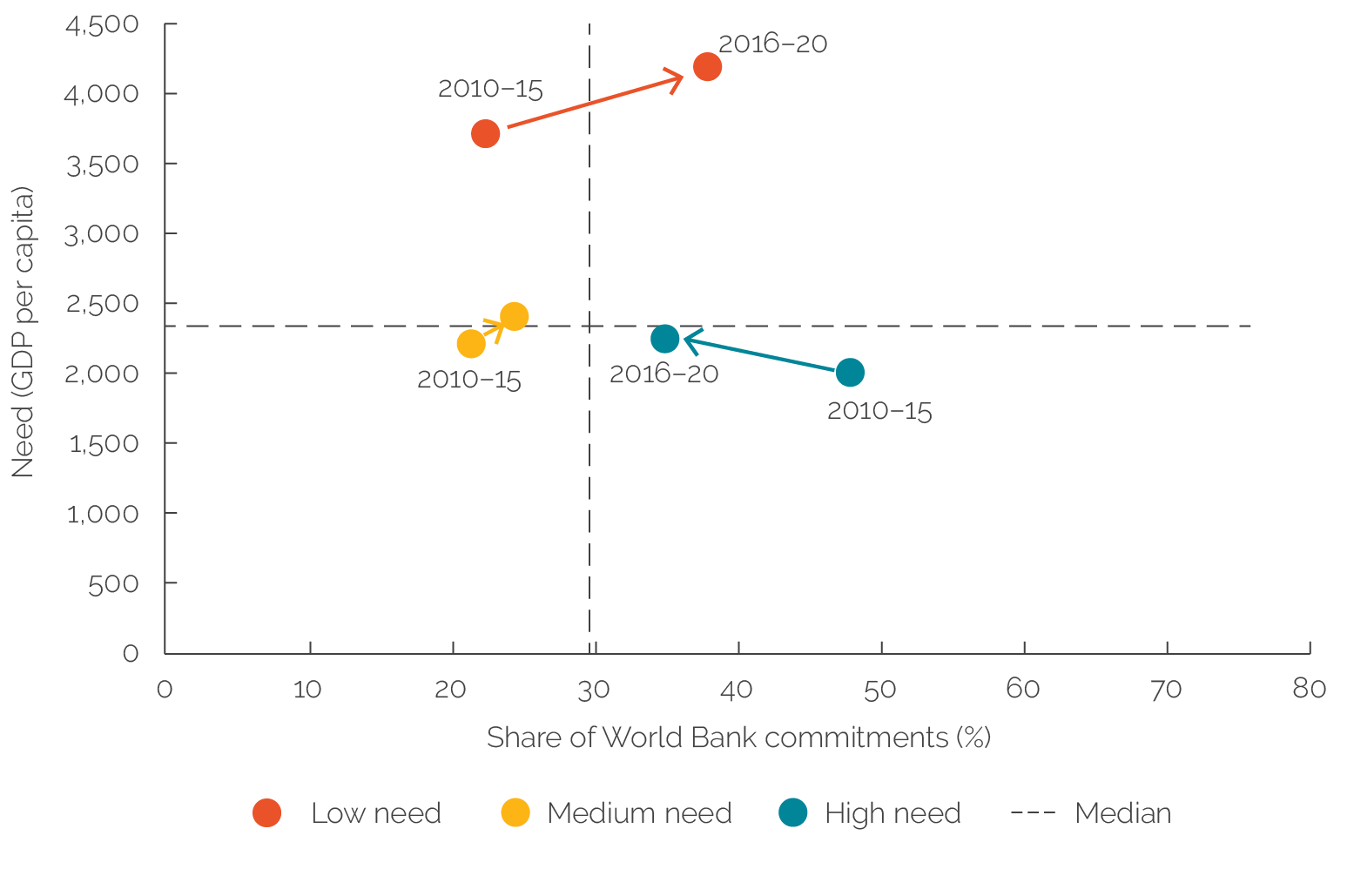

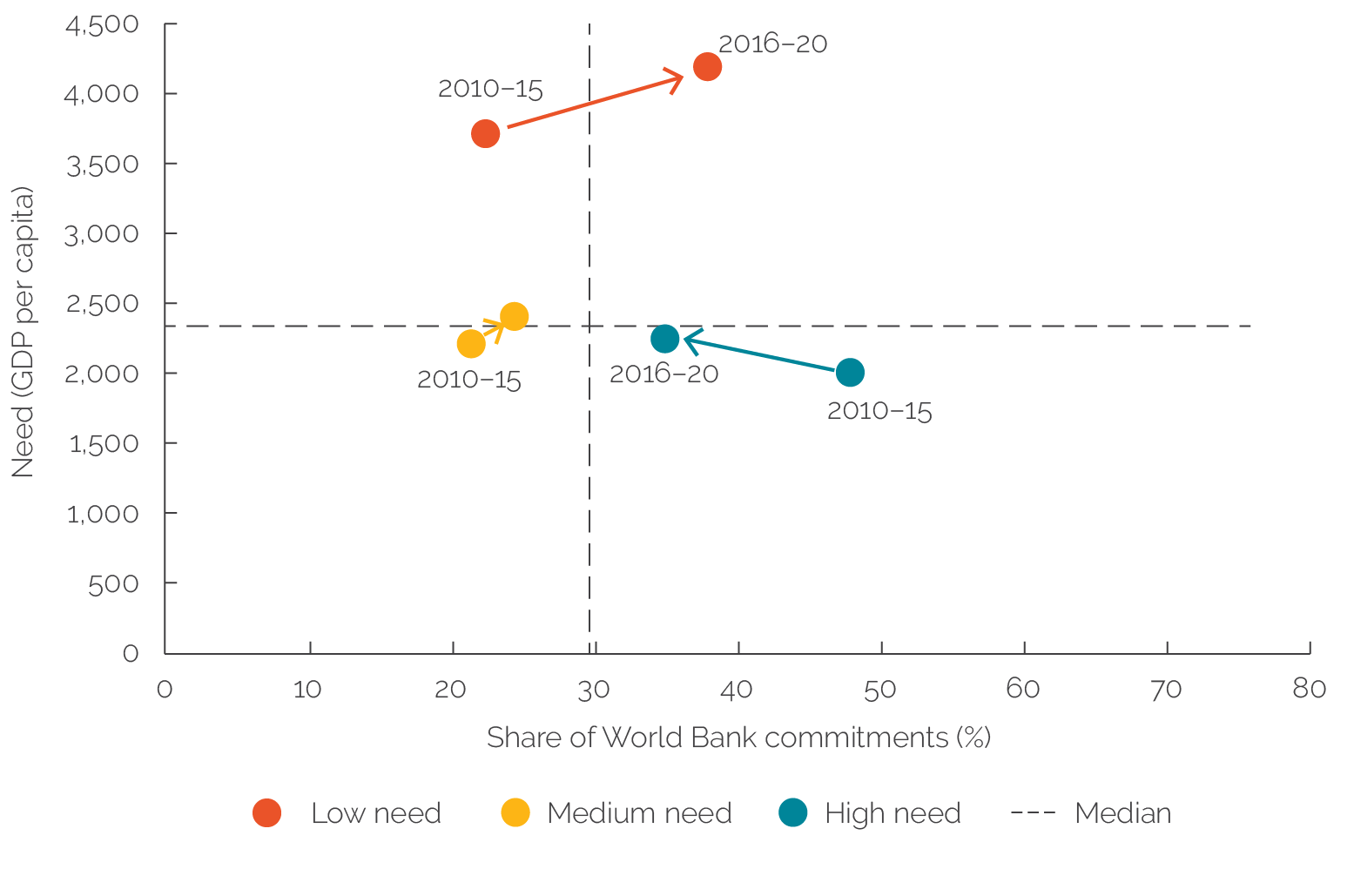

The balanced development of Moroccan territories was a cornerstone of the 2011 constitution but, until the latest strategy, received limited World Bank attention. The 2011 constitution, and the Organic Law No. 113-14 of July 15, 2015, enshrined subsidiarity and advanced regionalization principles. Morocco’s 12 regions, 17 deconcentrated wilayas (regional deconcentrated unit), and 1,503 municipalities were given mandates from the central government to cover the infrastructure and basic social service needs for their residents. However, subnational governments have struggled to deliver on these mandates because of financing challenges and weak institutional capacity. The territories struggle to attract private capital because of regulatory and political risks for investors and rent-seeking behaviors. As a result, territories continue to rely on the central government to finance infrastructure and basic services. Moreover, weak accountability for providing these services leaves municipalities without a strong incentive to perform effectively (World Bank 2020b). High regional imbalances in wealth, human capital, and access to quality services are also persistent (CSMD 2021). However, despite the World Bank’s commitment to reducing regional disparities, the share of financing going to lagging regions decreased between the first and second parts of the evaluation period (figure 5.1 and appendix D). As shown in chapter 3, the Bank Group has provided major financing and advisory services to improve Morocco’s business environment, but until 2018 that support concentrated on Casablanca, the business and economic center of Morocco and the focus of the DB survey. Moreover, most of the World Bank’s technical assistance, ASA, and capacity-building efforts have supported the central government, not the territories. It was not until the latest CPF (FY19–24) that the World Bank made territorial inclusion a priority and started experimenting with financing subnational governments.

More recently, the Bank Group has experimented with approaches to engage subnational authorities. The FY19–24 CPF made reducing regional imbalances one of its three overall priorities, and since then, the Bank Group has tested various ways of engaging subnationally. Three examples illustrate the range of this experimentation. The first example is the Bank Group’s support for CRIs—the regional one-stop shops for business climate reforms. Earlier in the evaluation period, the Bank Group did not interact much with CRIs. However, a 2015 Cour des Comptes (Audit Court) evaluation of Morocco’s 12 CRIs shed light on their institutional weaknesses and prompted both IFC and the World Bank to engage CRIs directly to improve their services to firms and investors, starting with pilot operations in Casablanca and Marrakech-Safi. Both operations required the Bank Group and the CRIs to establish effective working relationships and develop a coordination mechanism with central authorities. The second example is the World Bank’s support for municipal authorities through the $200 million Casablanca Municipal Support Program PforR, which calibrated DLIs at the municipal level and where funds go to municipal budgets. This municipal-level approach achieved good results by easing requirements for starting businesses, helping businesses obtain construction permits, and digitizing business registrations—a process that has since been adopted nationally. The third example is IFC’s use of advisory services to engage municipalities directly. In June 2020, IFC launched a $900,000 advisory services project to improve business competitiveness in the Marrakech-Safi municipality. The project aims to reduce public procurement payment delays for SMEs, promote private investments in aftercare activities, and build the capacity of the Regional Business Environment Committee.

Figure 5.1. Share of World Bank Commitments to Subnational Regions, 2010–20

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Over the period 2010–20, the World Bank commitments were primarily allocated to higher-need regions (42.2 percent of commitments), 33.1 percent of the World Bank commitments were allocated to lower-need regions, and 24.8 percent were allocated to medium-need regions. In the figure, the data are disaggregated across the periods 2010–15 and 2016–20 and displays the evolution of the regional distribution of World Bank commitments across the two periods. The level of need is represented by gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (y-axis), but a similar conclusion can be reached when using other indicators as a proxy for the level of need (such as nighttime lights data).

The Bank Group has also experimented with approaches to fill subnational financing and capacity gaps. The World Bank’s Morocco Infrastructure Review estimates that Moroccan municipalities require DH 22.2 billion per year to cover their equipment and infrastructure costs, but they currently mobilize only about DH 4.5 billion per year. As a result, these municipalities depend on the central government to finance these needs. In response, the World Bank and IFC have experimented with different approaches to help local authorities address these gaps. For example, in 2020, the World Bank funded a $300 million Municipal Performance Program PforR in partnership with the Agence Française de Développement (French Development Agency). The program provides performance-based grants to help municipalities improve services and attract private financing. It has tested several innovative approaches, including helping cities mobilize capital through PPPs, shifting the responsibility for local investment planning from regional organizations to the Ministry of Interior, developing an intermunicipal mechanism to coordinate investments, and providing on-demand technical assistance to participating municipalities and intermunicipal institutions. For its part, IFC is financing $25 million in advisory services to improve the road network in the Fès-Meknès region and a $100 million operation for Casablanca’s two new tramway lines—the first such investment with a local government in the Middle East and North Africa Region without a sovereign guarantee. In interviews, Ministry of Interior counterparts and other development actors supported the Bank Group’s experimentation and acknowledged several risks. For example, starting with higher performers makes sense in the experimentation stage but also means that the World Bank has committed more toward lower-need regions in the second part of the decade than in the first (figure 5.1).

Box 5.1. Outcome: The World Bank Group’s Contributions to Human Capital Formation and Protection

- The World Bank Group helped Morocco implement difficult reforms in teacher recruitment and training. The inadequate teacher selection process and teacher training were among the main causes of Morocco’s low-quality education (CSEFRS 2014). To address these issues, the World Bank’s 2010–13 development policy financing series’ prior actions revamped preservice training, transferred teacher training responsibilities to universities, and strengthened the merit-based recruitment process. These reforms met resistance from teachers’ unions and were undermined by the government’s decision to hire contract teachers with limited training to address teacher shortages. Learning from the limited progress of the development policy financing, the World Bank reengaged in the sector in 2017 to prepare a Program-for-Results operation (signed in 2019) that tackled governance constraints to teacher recruitment and training. The operation rolled out a new training and induction model for new hires, developed a plan for teachers’ professional development, and developed psychotechnical tests for teacher recruitment.

- The World Bank advanced early childhood development (ECD) as a national priority. The World Bank’s analysis on ECD raised the government’s awareness of the negative impacts of low-quality ECD on human capital outcomes. The World Bank used the analytics and convening power of the Human Capital Project to convince authorities to invest efforts in ECD, which led the government to make early childhood education compulsory. The World Bank’s Program-for-Results also incentivized the government to invest in quality as it improves the national coverage of early childhood education. The program developed a training system for preprimary educators, established robust measurement systems, and implemented quality standards for early childhood education providers. The World Bank also supported the third phase of the National Initiative for Human Development to address its shortcomings with ECD.

- The World Bank helped Morocco decentralize its education system through trial and error. Morocco’s decentralization agenda started in 2000 with the creation of Regional Education and Training Academies (AREFs) but by 2010 had made limited progress. The World Bank’s development policy financing series advanced decentralization by having the ministry devolve 50 percent of human resource management to AREFs. However, the low capacity of AREFs led to weak results. Learning from these experiences, the World Bank’s Program-for-Results used financial analyses to identify bottlenecks, mobilized international expertise to address weak AREF capacity, and introduced performance contracts backed by rigorous financial and performance data.

- The World Bank helped Morocco rapidly transform its social protection system. The World Bank’s analytics helped eliminate regressive subsidies and build a modern and progressive social protection system. Early in the decade, the World Bank partnered with the National Observatory for Human Development to assess the political and technical feasibility of reforming the country’s main social protection programs—Regime d’Assistance Medicale, DAAM (Aide Directe aux veuves en situation de précarité ayant des enfants orphelins à charge), and Tayssir. The World Bank subsequently supported Morocco’s development of the National Population Registry and the Unified Social Registry using biometric identification tools to generate unique identifiers. Both platforms are being successfully piloted in Rabat with a national rollout expected in 2023. The Unified Social Registry will become the only entry point for all social assistance. These building blocks of a modern social protection system enabled the rollout of a very ambitious set of reforms adopted during the COVID-19 pandemic that set out to increase the social protection coverage to an additional 11 million Moroccans (as announced by the king’s October 2020 speech and enacted in the National Framework Law of 2021).

- The World Bank made more modest contributions to health system reforms. The World Bank was absent from Morocco’s health sector between 2000 and 2015. Its reengagement through a Program-for-Results focused on subnational territories, the prevention and treatment of noncommunicable diseases, and equitable access to basic health services for children and mothers. The World Bank’s introduction of mobile health vans was a useful innovation that helped in the country’s COVID-19 response. The World Bank also partnered with the World Health Organization and the Ministry of Health to organize the National Conference on Health Financing in June 2019 with recommendations that ultimately informed the health financing aspect of the social protection and health reforms that were initiated in 2020. However, the World Bank’s attempt to introduce a national health management information system did not materialize.

- The World Bank’s contributions to improving the labor force participation of women and youth have not matched its diagnostics and have been fragmented and small in scale. The World Bank’s in-depth diagnostic work on gender inequality has not translated into strategic action on labor force participation. The few operations that have focused on youth inclusion were small in scale, focused heavily on entrepreneurship, and did not generate sufficient learning on active labor market programs. Likewise, the World Bank has yet to gain traction with the government to translate its thorough diagnostic of the barriers to female labor force participation into action.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

- See World Development Indicators 2020.

- The exception was the large, planned Program-for-Results operation to support Morocco’s National Initiative for Human Development (P116201) in 2012.