The World Bank Group's Engagement in Morocco 2011-21

Chapter 2 | Getting to Policy Coherence

Highlights

Many development actors operate in Morocco, and Moroccan authorities are selective about which partners they turn to for policy advice.

In this crowded environment, the World Bank Group used its global benchmarking data, expertise in new development approaches, and capacity for cross-sectoral support to inform Morocco’s policy reforms.

The World Bank’s data and knowledge work, paired with a flexible policy dialogue, had significant impact on policy reforms. To inform policy content, the Bank Group capitalized on its management of global benchmarking data to initiate dialogues on policy reforms on private sector development, early childhood development, and institutional reforms. World Bank’s analytics also revealed the depth of development problems in several sectors, such as education, social protection, and disaster risk management, prompting policy action in each domain.

The World Bank limited its role to just-in-time analytics when working with the government on subsidy and pension reforms because the World Bank’s prominent presence could have complicated those politically sensitive reforms, thereby prioritizing policy impacts over recognition for its work.

The World Bank used the preparation and dissemination of the Country Economic Memorandum as a platform to engage in policy dialogue on critical reforms and navigated Morocco’s political economy effectively.

This chapter assesses the relevance of the Bank Group’s country engagement and its effectiveness in shaping Morocco’s policy reforms. According to the royal commission on the NDM, Morocco’s first systemic obstacle to development is its limited policy coherence, with a disconnect between the country’s policies and its development goals. This chapter shows that, to effectively shape Morocco’s policy reforms and affect Morocco’s policy coherence, the Bank Group gained access to policy makers (see the Gaining Access section), informed the content of policies (see the Informing Policy Content section), and supported the country in reshaping the development model. The Bank Group succeeded in doing so despite the government’s selective receptivity to development partners’ advice. More specifically, the Bank Group used its global benchmarking data, tailored its knowledge products to the national context, guided the government in new development approaches, worked from the background on politically sensitive reforms, and applied a flexible approach to government engagement to reap a “policy influence dividend.”

The lack of coherence across Morocco’s sectoral strategies has undermined the country’s development progress. Since the early 2000s, the Moroccan government has relied on sectoral strategies—such as the Solar Plan, the Emergence Plan, PMV, Numeric Morocco, and the 2020 Vision for Tourism—to develop its economy. As mentioned in chapter 1, the Bank Group was devoted to supporting these sector strategies through single-sector budget support DPF during FY10–13. However, the coordinated design and implementation of some public policies was challenging due to various factors, such as resistance to change of some stakeholders and ineffective coordination mechanisms. Policy coherence was a central theme in the king’s speech in 2012 and in the governance forum in 2013. Several national diagnostics also highlighted these challenges (MAGG 2015a, 2015b). For example, a detailed study of Morocco’s export competitiveness, conducted by Morocco’s Royal Institute for Strategic Studies in 2013 and updated by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in 2017, highlighted the costs from inconsistent trade and industrial policies (IRES 2013; OECD 2017a). Moreover, the Emergence Plan was adopted too late (2005) to allow Morocco to take advantage of the trade agreements it signed in 1998. As a result, Moroccan exports were not competitive, and tariffs were not adjusted to support the growth of Moroccan businesses. Government studies also show incoherency in agricultural and industrial policies, which negatively affected agribusiness development. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s multidimensional study of Morocco’s development over two decades concluded that the lack of coherence directly influenced the public sector’s effectiveness and the country’s social and economic performance (OECD 2017a, 2018c). The Bank Group recognized these issues and adjusted its strategy during the FY14–17 strategy period to promote more multisectoral approaches. Examples, results, and lessons from World Bank support to multisectorality are described in chapter 4.

Gaining Access

Development partners tend to have limited influence at the agenda-setting stage of the policy process in Morocco. The country has a crowded aid market, with many potential partners available to support its development agenda. The Moroccan government also communicates relatively infrequently with partners according to a 2014 reform effort survey by AidData (Custer et al. 2015). The survey found that, on average, development partners have limited influence when setting the agenda of the policy process in Morocco. According to the survey, Morocco ranked among the 10 countries least influenced by development partners in determining which reforms to pursue. Interviews with more than 20 government officials and 10 development partners confirmed that Morocco is a selective client, with a sharp eye for discerning partners’ comparative advantages and deciding when to listen to their advice or not. In interviews, government counterparts had a clear view of the circumstances under which they would take the Bank Group’s advice or turn to other donors or consultancy firms for recommendations. In interviews, other development partners felt that, at times, it was more challenging to get “the ear” of Morocco’s decision makers and to coordinate among partners with whom the government tended to prefer operating bilaterally.

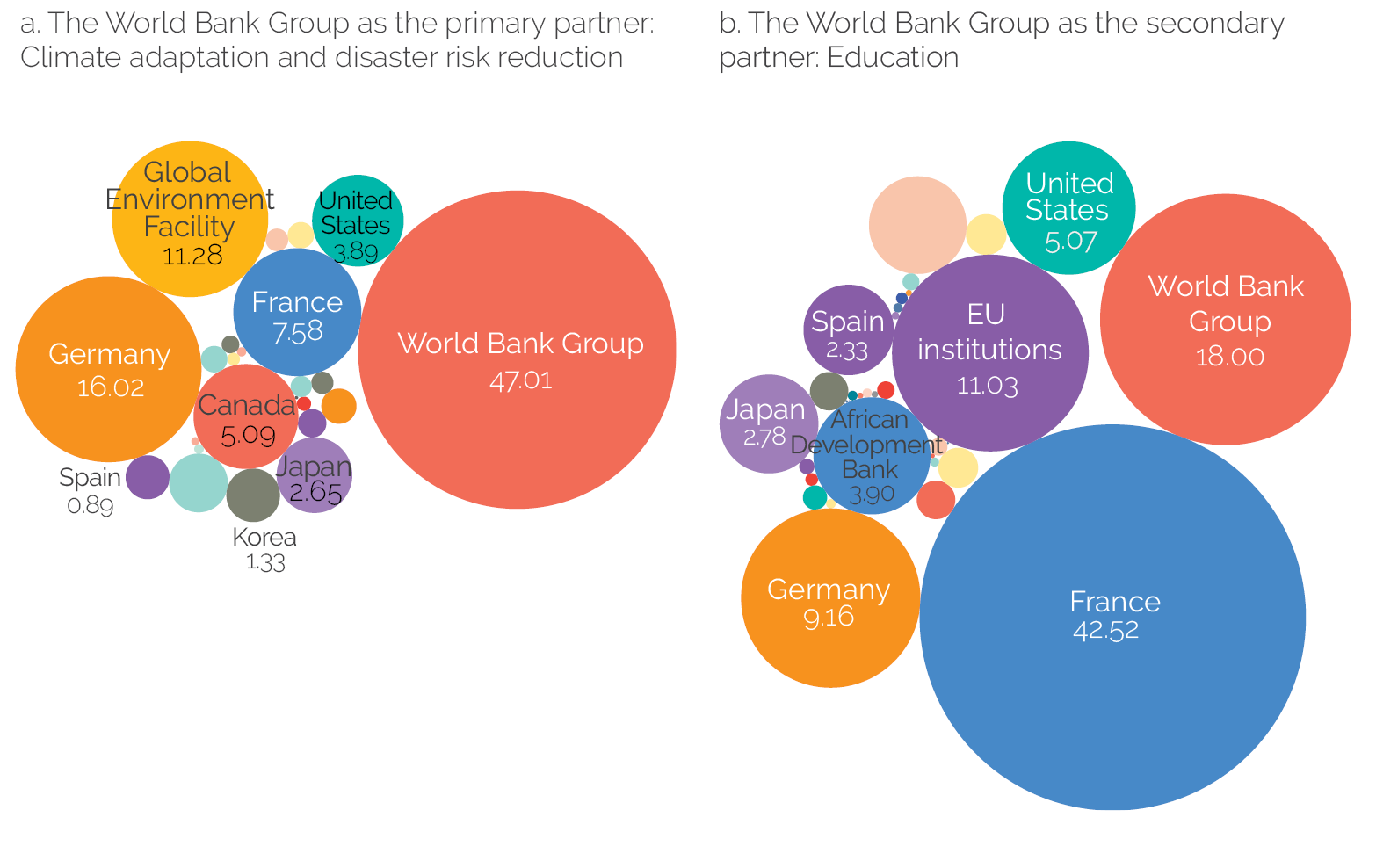

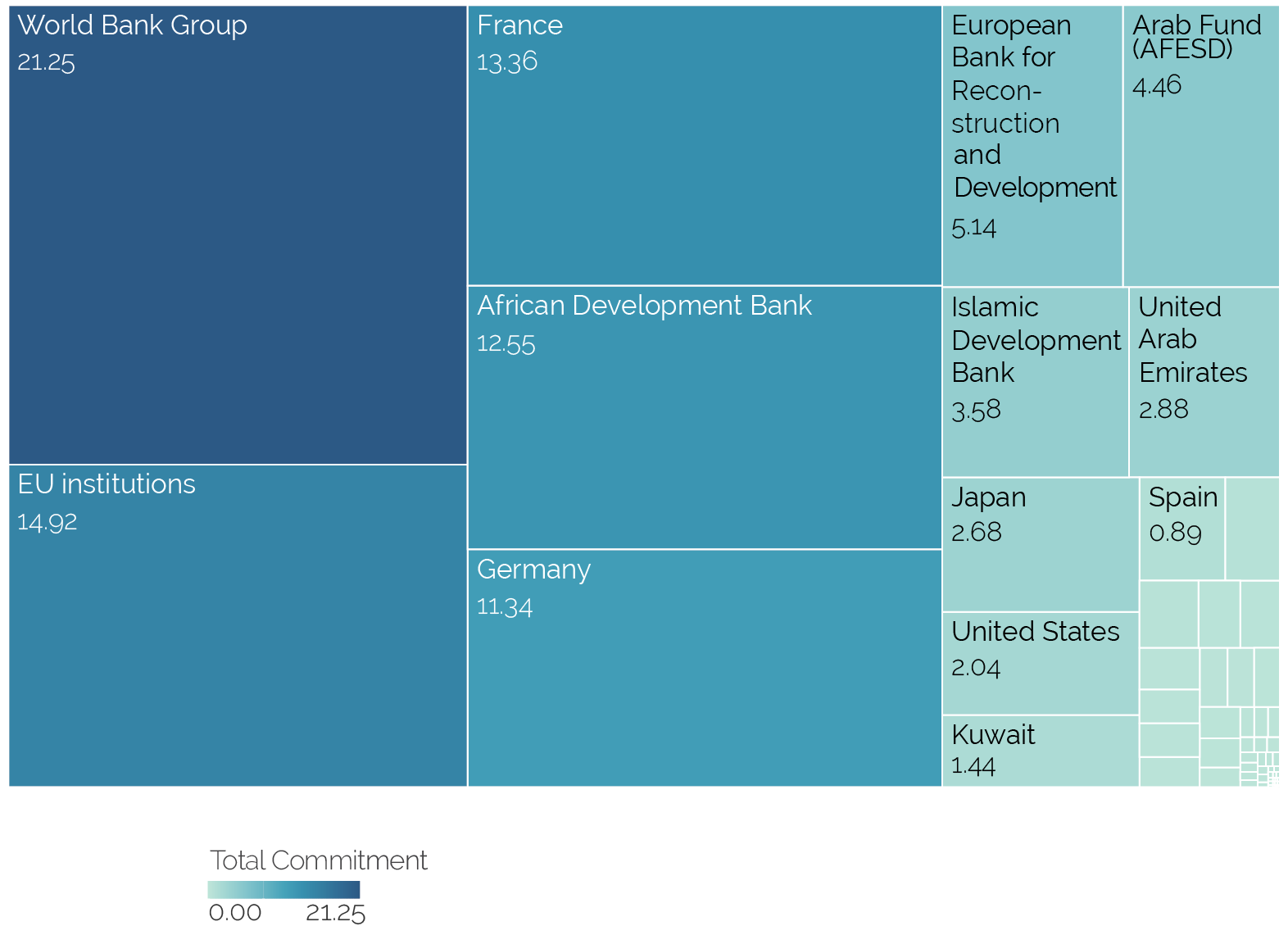

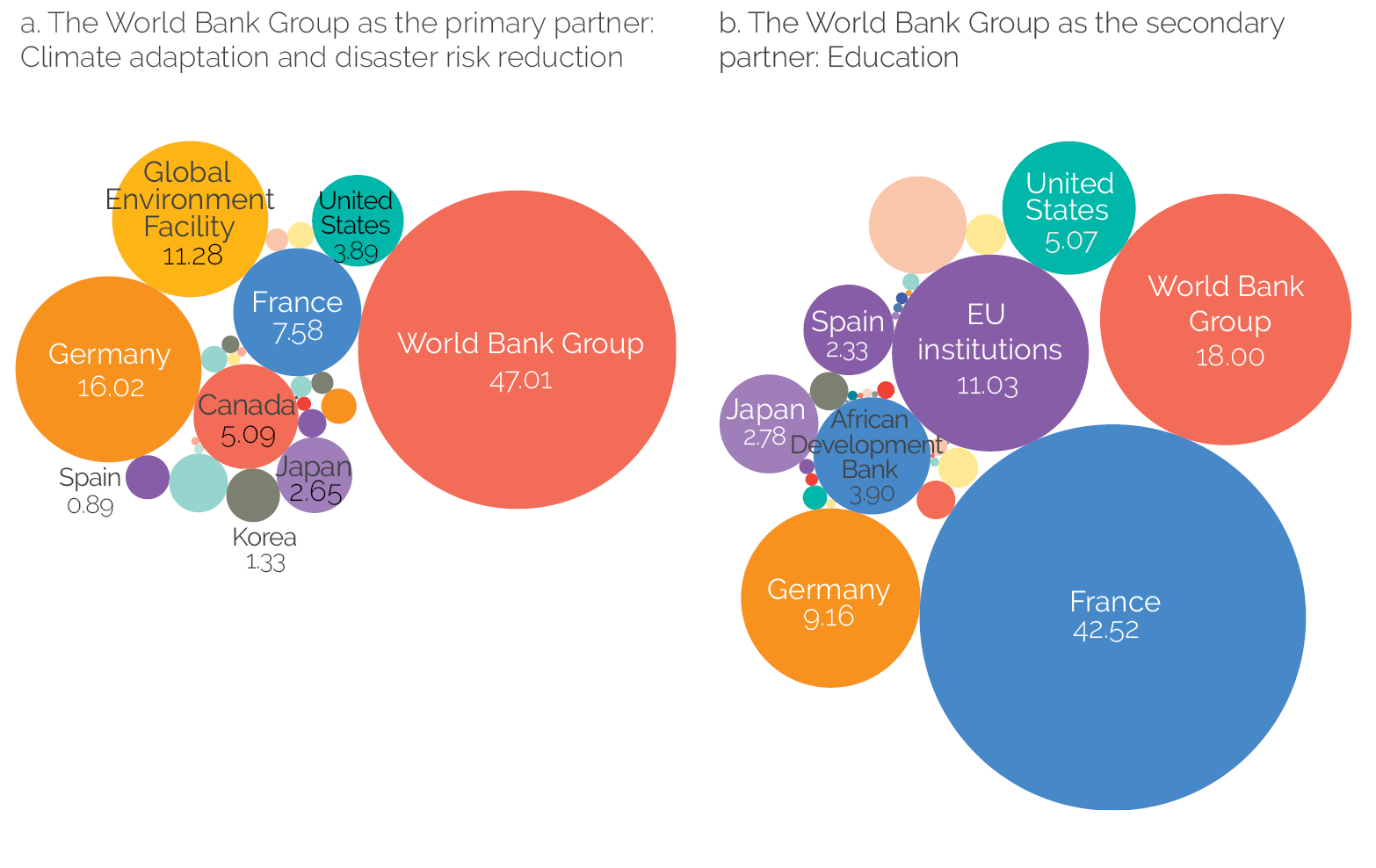

In this crowded environment, the Bank Group has gained the trust of Moroccan authorities to have a lead advisory role in key policy domains. Over the past decade, the Bank Group has been Morocco’s lead development partner, as measured by overall commitment amounts (figure 2.1). It was the primary partner in climate adaptation, public sector governance, business environment, and MSME development, among others. The Bank Group played a secondary role in other domains, such as education (as shown in figure 2.2), and an even more limited role in health and gender equality (as shown in appendix C). In the areas where the World Bank has played a lead role, it has also exercised its convening power despite the limited incentives for donor coordination. All interviewed donors appreciated the World Bank’s efforts to mobilize the Group of Main Partners (Le Groupe Principal des Partenaires).

Figure 2.1. Distribution of Total Commitments by Partner, 2010–20 (percent)

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Creditor Reporting System 2022.

Note: Commitment figures for the World Bank Group are as reported in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Creditor Reporting System for comparability. AFESD = Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development; EU = European Union.

The Moroccan government had a clear opinion of the Bank Group’s comparative advantages. In interviews, government counterparts perceived the Bank Group to have five key comparative advantages over other development partners: (i) the Bank Group’s innovativeness, (ii) its capacity to bring the best expertise across a range of topics to Morocco, (iii) its ability to frame solutions for cross-sectoral challenges, (iv) its readily and quickly available analytics, and (v) its knowledge-brokering power that facilitates South-South learning. When the Bank Group mobilized these comparative advantages, it was more likely to gain a “seat at the table.” Examples of how the Bank Group leveraged these comparative advantages are included in the following chapters.

Figure 2.2. Relative Size of World Bank Group Commitments (percent)

Figure 2.2. Relative Size of World Bank Group Commitments (percent)

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Creditor Reporting System 2022.

Note: Commitment figures for the World Bank Group are as reported in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Creditor Reporting System for comparability. Activities not mapped to any working area are excluded from the calculations. EU = European Union.

Informing Policy Content

The Bank Group capitalized on its management of global benchmarking data to initiate dialogues on policy reforms. Interviews with Bank Group staff and development partners and an analysis of media sources and high-level policy statements indicate that the government pays close attention to its ranking on global development indicators and is sensitive to “data optics.” Over the past decade, the Bank Group has capitalized on this interest by using its global benchmarking publications to initiate dialogues with Moroccan authorities in several policy domains. Specifically, the Bank Group was able to use the Changing Wealth of Nations indicators, the Human Capital Index, and the Doing Business (DB) rankings to initiate dialogues and influence Morocco’s policy agenda on public sector governance, education and early childhood development (ECD), and market competitiveness and the business environment (discussed further in chapter 3).

The World Bank’s data work revealed the depth of development challenges in education and ECD, prompting policy action. The World Bank’s data work revealed three troubling new human development trends. First, the World Bank assembled data from four surveys between 2003 and 2016 to show that, from 2015 to 2016, only 43 percent of Moroccan children ages four or five years were enrolled in preschool; that figure was only 28 percent in rural areas (El-Kogali et al. 2016). It also revealed for the first time that the poorest Moroccan children were much less likely (16 percent) to benefit from development activities compared with the richest children (58 percent). Second, the World Bank was the first to assess the impact of Morocco’s National Initiative for Human Development (INDH) on ECD outcomes, revealing the INDH’s shortcomings. Third, the World Bank’s release of the Human Capital Index showed that shortcomings in ECD and education quality meant that Moroccan children born today will be only half as productive as if they had benefited from full health and learning. This result was lower than the regional average. The World Bank mobilized all this evidence to open a window for policy dialogues with the government on preschool education. These dialogues and analytical work became particularly useful and aligned with the king’s 2018 speech that enshrined preschool education as a national priority and called for it to gradually become compulsory. After the speech, the government launched a national program to ensure universal access and improve the quality of preschool education. This work paved the way for the 2019 signing of a $500 million PforR operation—the Morocco Education Support Program.

The World Bank’s analytical support informed Morocco’s subsidy reforms at a time when skyrocketing subsidy prices demanded these changes. All government counterparts interviewed for this evaluation argued that one of the Bank Group’s comparative advantages is its ability to quickly mobilize “top-notch” knowledge and expertise when Moroccan authorities require it. For example, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund engaged in a long-standing dialogue with Morocco on its costly and unequal subsidy program, which favored the wealthiest households (World Bank 2014c). The direct cause for the subsidy reform was the threefold increase in oil prices between 2010 and 2012 that almost tripled the government’s food and energy subsidy bill from less than 2.5 percent of GDP to 6.5 percent and made subsidy reforms urgent for the government’s fiscal sustainability. As a result, the government requested the World Bank’s analytical support, which included technical assistance and both stand-alone and programmatic ASA during FY11 and FY12. The World Bank responded by modeling various reform scenarios that synthesized the experience of 20 countries that had undertaken such reforms. The World Bank also assessed the political economy of the reforms to propose an ideal implementation pace and compensatory measures. This support informed the 2014 Budget Law, which removed subsidies on the domestic price of diesel, gasoline, and industrial fuel oil. By 2019, the share of subsidies had fallen to 1.6 percent of GDP. High-level government officials involved in the reforms said that the Bank Group’s early assistance decidedly shaped their decision-making.

Building on the success of the subsidy reforms, the World Bank deployed a large body of analytical work to help Morocco set up the foundation for a modern social protection system. In parallel to the subsidy reform, Moroccan authorities were considering options for strengthening the effectiveness and efficiency of their social programs, and after November 2013, the government consulted widely to assess the feasibility of social programs targeting. At the end of the 2000s, the World Bank had already conducted a comprehensive diagnostic of the state of Morocco’s social programs and drafted options for a social protection strategy for the country. It mobilized this rich evidence base and conducted additional analytics to assess the technical, financial, and political feasibility of Morocco’s core social safety net programs—Regime d’Assistance Medicale, DAAM (Aide Directe aux veuves en situation de précarité ayant des enfants orphelins à charge), and Tayssir (World Bank 2014b; World Bank and ONDH 2015). The reports’ recommendations were widely disseminated and used in dialogue with key ministries—the Ministry of General Affairs and Governance, the Ministry of Interior, and the Ministry of Finance. The immediate outcome of the World Bank’s knowledge work and policy dialogue was the engagement on building a national and unified social registry (see chapter 4). When the COVID-19 pandemic prompted further reforms, which were announced by His Majesty King Mohammed VI in October 2020 calling for “social welfare coverage for all Moroccans” with an ambitious timeline, the World Bank’s preparatory analytical work, continuous technical assistance, and investments in social protection systems became the backbone of the ongoing reform, which aims to expand social protection and health coverage to an additional 11 million workers by 2024 (as called for by the National Framework Law of 2021).

The World Bank provided upstream advice and cross-sectoral solutions to reform Morocco’s disaster risk management (DRM). In 2004, a devastating earthquake struck the city of Al Hoceima, which opened a policy window for shifting Morocco’s DRM approach toward preparedness. At this point, the World Bank provided upstream advice to Moroccan authorities and launched, along with the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, a comprehensive assessment of disaster risk in Morocco (World Bank, GFDRR, and SDC 2013). The analytical work on the costs of disasters stimulated a partnership with the government on DRM and improved government agencies’ awareness and understanding of disaster risks and the cross-sectoral nature of DRM (World Bank, GFDRR, and SDC 2013). Despite delays, the dialogue progressed toward a $200 million PforR operation that was codeveloped with the Ministry of Interior, a powerful ministry playing a vertical coordination function. The operation introduced a new financing and capacity-building mechanism, which enabled local authorities and civil society organizations to acquire funding for disaster preparedness projects across sectors. It also set up a private insurance system for households and businesses, and it compensated uninsured people through a national solidarity fund that has been operational since January 2020. In 2019, the World Bank approved a follow-on DPF with a catastrophe deferred drawdown option with prior actions that would complete the solidarity fund’s governance structure, establish a sustained financing mechanism, and provide a framework for registering disaster victims. The catastrophe deferred drawdown option was disbursed in April 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic triggered the emergency against which the loan disbursed.

The World Bank ensured its impact on Morocco’s pension reforms by strategically limiting its support to just-in-time analytics. The World Bank chose this strategy when its involvement could be problematic for the government’s reform agenda. Morocco’s pension reforms provide a good example of this dynamic. Various estimates from the early 2000s predicted that the public pension system for civil servants, the Caisse Marocaine des Retraites, would be unsustainable (Robalino et al. 2005). In the mid-2000s, the World Bank tried to convene the various entities involved in the fragmented pension system toward a common view. However, the unions distrusted the process, in part because of the World Bank’s participation. In the early 2010s, the government convened a National Technical Commission consisting of many stakeholders to pension reforms. However, several key stakeholders, such as retiree associations and civil service contributors, had a negative perception of the World Bank. As a consequence, the World Bank chose to maintain a low profile and not participate directly in the commission. Instead, the World Bank provided a technical review of the proposed reform and technical assistance on parametric adjustments to the retirement age and contribution and accrual rates. The commission’s work led to the inclusion of a comprehensive, three-phase pension reform in the 2014 Budget Law. Once the law was approved, the World Bank supported the reform’s first phase through its FY13 Capital Market Development and SME (small and medium enterprise) Finance DPO ($300 million) with prior actions that would increase the retirement age and contribution rates and reduce accrual rates. In December 2017, Morocco passed a law establishing a pension program for various categories of workers, including independent and nonsalaried workers. The World Bank’s involvement was again strategically minimized during the implementation phase, but the World Bank’s just-in-time data and technical assistance work were key to passing the reforms.

When disagreement on the industrial policy caused policy dialogue to sour, the Bank Group continued to pursue analytical work on the topic, which ultimately gained traction. Morocco’s Emergence Plan (2005) has been the cornerstone of the country’s industrial policy for the past decade. It relies on subsidies, advantageous taxes, major public investments in infrastructure, and incentives to attract major foreign direct investments. However, many aspects of the Emergence Plan were at odds with the Bank Group’s preference for a private sector–led growth model. In the early 2010s, the Ministry of Industry perceived the World Bank to be insufficiently flexible on Morocco’s Emergence Plan, limiting the World Bank’s direct influence on the agenda, including tax reforms or the industrial development agenda for several years. However, both the World Bank and IFC continued to pursue analytical work on the topic and showed that policy measures at the core of the Emergence Plan created a highly stratified private sector that mostly benefited SOEs and large multinational firms (Chauffour 2018; IFC 2019; World Bank 2006, 2014c, 2018). The Bank Group showed that the model failed to trickle down to smaller domestic firms and that it did not raise private finance in the sectors essential for continued growth. Through Enterprise Surveys and other analytical work, the Bank Group and the International Monetary Fund demonstrated the distortionary effect of the plan’s tax system on entrepreneurship—creating barriers for new entrants. Ultimately this body of evidence gained traction and was considered in the NDM.

The World Bank’s flexible stance on Morocco’s agricultural policy allowed it to directly influence that policy and remain a trusted partner to the government. Morocco’s agricultural policy—PMV—started in the late 2000s and aimed to make agriculture the country’s main driver of economic growth and job creation. The PMV was originally an export-led sectoral strategy to maximize the production of industrialized, commercial agriculture through agribusiness investments. Parts of the PMV ran counter to the World Bank’s recommendations on agricultural development. For instance, the World Bank had a different perspective regarding the PMV’s focus on public investments and incentives to intensify agricultural production for particular crops or regions. This included the second pillar of the PMV’s focus on smallholders. The World Bank’s diagnosis was that this could widen distortionary effects and prevent the natural movement of resources to more productive activities. At the same time, as the World Bank staff explained, the World Bank team was keen to continue discussing agricultural policy and not be sidelined. To do this, the World Bank worked within the framework of the PMV as a whole but limited its support to technical and financial aspects of the PMV where the World Bank had comparative advantage, ceding to other donors the aspects that ran counter to the World Bank’s ideas. The trust established by this partnership allowed the World Bank to maintain a key seat at the table and effectively coordinate partner support in the sector. The review of World Bank operations in the agriculture sector shows that the World Bank was selective in the areas it supported, for example, by focusing on removing market distortions and improving knowledge and resource availability for smallholders and subsistence farmers.

The World Bank successfully used the preparation and dissemination of the CEM as a platform to engage in policy dialogue on sensitive reforms. The World Bank’s 2011 global report, The Changing Wealth of Nations: Measuring Sustainable Development in the New Millennium, which ranks countries on their intangible capital,1 triggered useful policy dialogues on Morocco’s development model. The report shows that Morocco had a lower GDP than resource-rich neighboring countries, such as Algeria, but that Morocco also had relatively higher wealth rankings when intangible capital was calculated. Intangible capital refers to intangible assets such as human, social, and institutional capital. These favorable rankings made the front page of a high-profile Moroccan newspaper, L’Economiste, and captured the attention of authorities who called on the Economic, Social, and Environmental Council (Conseil Économique, Social et Environnemental; CESE) and the Bank Al-Maghrib (BAM) to study how to further enhance Morocco’s intangible capital.2 The World Bank saw an opportunity to capitalize on the moment. It acted as an adviser to the CESE report but also framed the CEM with a focus on what Morocco needed to do to increase its intangible capital. Unlike typical CEMs, which tend to be developed by a small internal World Bank team, this CEM was produced with key officials in Morocco’s government. These conversations helped the World Bank raise awareness on critical topics—such as the lack of impartiality of the judiciary, the lack of youth opportunities, and the existence of unfair market competition where privileged firms and SOEs crowd out the private sector—with government officials who would also ensure that the CEM did not cross any lines that would make it inaudible to policy makers. This collaboration between the World Bank and Moroccan authorities created joint understanding of the CEM’s proposals that became influential within the CESE and with other officials. In general, the CEM team had a high degree of autonomy to tailor the product to Morocco’s needs, which enabled them to produce a slightly less diplomatic but more ambitious document. The CEM, along with other technical work from the World Bank Group, provided useful input to the diagnostic and forward strategy of the NDM.

- The term “intangible capital” refers both to the human and social resources of a country (level of education and health) but also to institutional resources, such as the rule of law and governance.

- Speeches to the nation constitute an integral lever of policy guidance for the monarchy. Recurrent edicts commemorate events central to Moroccan history, including the anniversary of the Revolution of the King and the People, the king’s accession to the throne (Throne Day), the anniversary of the Green March, and other keystone events. The speeches also provide a platform to announce major policy reforms.