The Rigor of Case-Based Causal Analysis

Chapter 3 | Illustrating Findings

This section illustrates the nature of the findings that were generated, using the approach described, by demonstrating how the causal analysis materialized for one of the outcomes of interest: generating co-benefits. (For a detailed report of the full results, see World Bank 2018.)

The literature has discussed the degree to which carbon finance projects foster local community co-benefits as a useful secondary benefit from their outputs (Hultman, Lou, and Hutton 2020). The methodological approach used in the current study sheds significant light on the causal pathways that led to the different outcomes among these projects in regard to achieving this second objective.

First, the patterns of causality emerging from the cross-case evidence in the current study echo the literature in finding that afforestation or reforestation projects have the most potential among the types of projects studied to generate significant local co-benefits. Indeed, across all countries included in the current study, afforestation or reforestation projects examined generated direct co-benefits to local communities. The projects in these cases were developed under the BioCarbon Fund, one of three World Bank carbon funds with an explicit objective of generating co-benefits for the communities involved. However, the afforestation or reforestation cases examined in this study have inherent characteristics that require providing incentives to local communities, more so than other technologies such as renewable energy. In some cases, this is because the entity carrying out the project needed to enter into lease agreements with landholders; in other cases, the entity was a rural development agency, and the project was part of a larger rural development program with the dual goals of improving or diversifying community livelihoods and enhancing environmental conditions via better land management practices and sustainable forest management.

Second, beyond the nature of the technology that characterized the carbon finance intervention, cross-case analysis identified several other contributory factors. For one, all projects carried out in Colombia across all four technologies studied and all hydraulic projects carried out in China generated co-benefits. In most of the other cases studied, however, the projects provided limited community co-benefits or none at all.

For another, the within-case causal analysis traced the theorized pathways to co-benefits and identified the unique contribution of the five actors and variables for each project with a high degree of specificity and many explanatory details. Once the cross-case analysis within each technology was conducted, patterns of regularity emerged, as did patterns of exception. The within-case causal analysis was necessary to explain outlier patterns. For example, almost none of the hydro projects examined generated direct co-benefits to the communities they served, the exception being the hydro project in China. That project was carried out in an area of China with significant populations of ethnic minorities, triggering World Bank environmental and social safeguards, which in turn triggered an additional causal mechanism. Specifically, revenues generated from the certified emission reduction achieved in the project were used to finance the Ethnic Minority Plan prepared to comply with the World Bank’s Environmental and Social Framework safeguard policies. The plan included a range of beneficiaries, including a local health clinic, a temple, a road maintenance unit, and village education officials, thus generating co-benefits.

Analyses across cases within countries were also useful in identifying and testing the causal contribution of specific factors. For example, in all four cases in Colombia that were reviewed, the projects provided direct co-benefits to the communities the projects served, regardless of the technology involved. In all four cases, the World Bank’s Environmental and Social Framework safeguards policies enhanced the projects’ direct socioeconomic benefits to the communities they served. In the Jepiroche wind project, which was implemented in Indigenous peoples’ territory, the World Bank played an extremely prominent role and provided incentives for the implementation of its Environmental and Social Framework safeguards policies by offering a premium price in the ERPA, contingent on high-quality implementation of those policies.

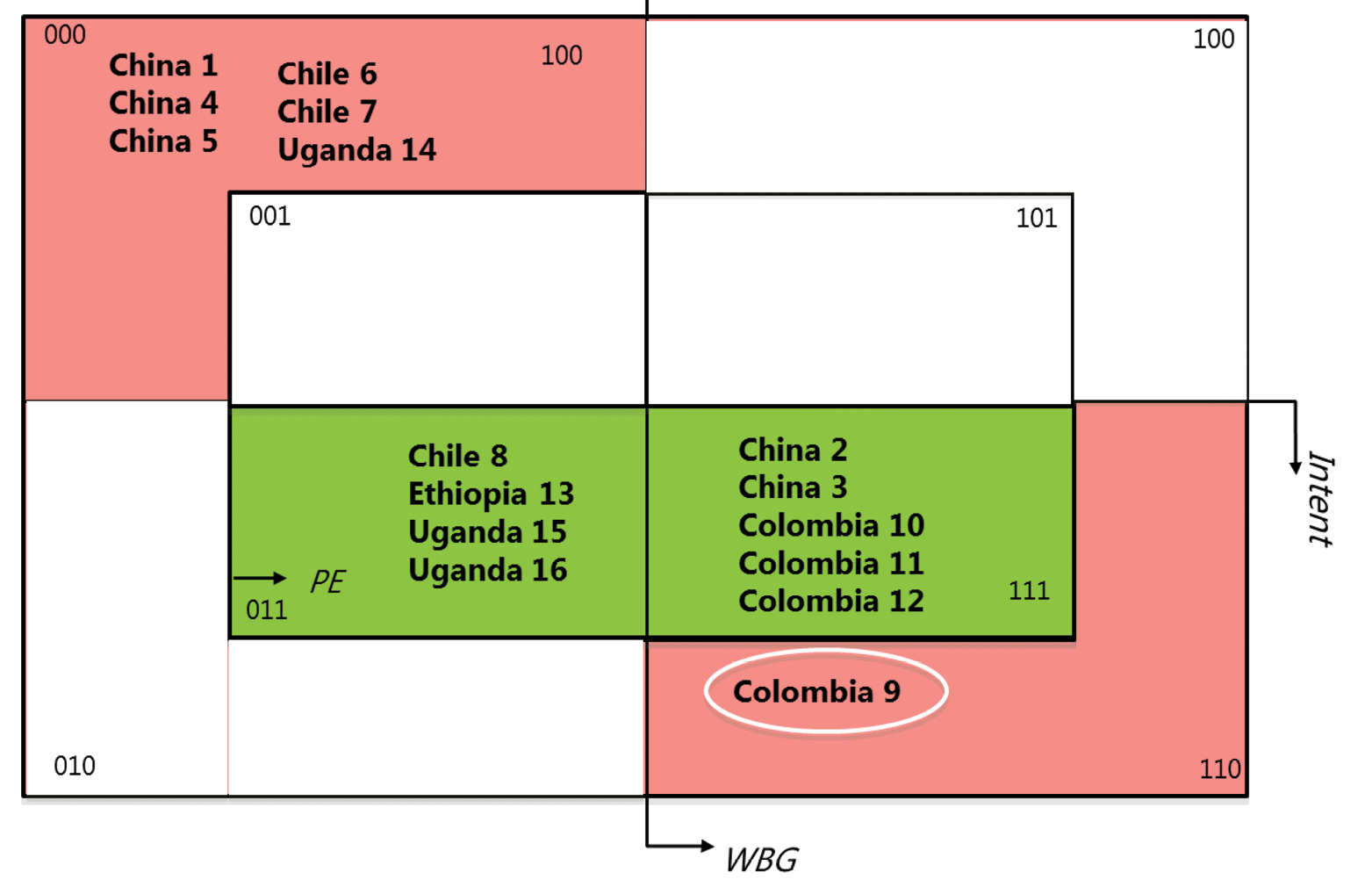

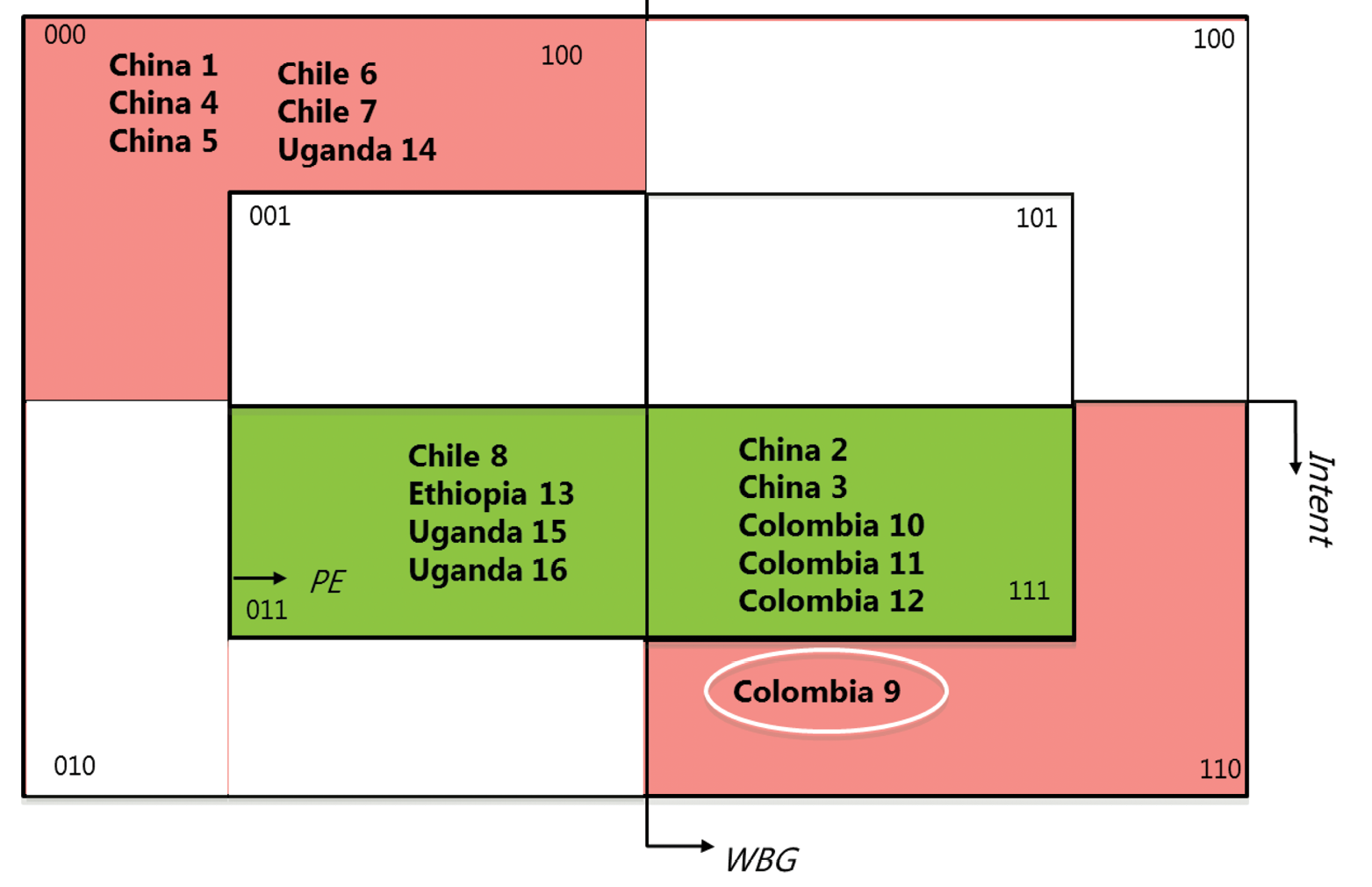

Finally, in addition to the patterns of regularity emerging from analysis by technology and country, application of the crisp-set QCA algorithm revealed two main causal pathways, one leading to positive outcomes and one leading to negative outcomes. As illustrated in figure 3.1 and table 3.1, the pathway to positive outcomes (the green boxes in the figure) combines a strong intent to achieve co-benefits at the project design stage with a demonstrated commitment, throughout the project, to achieving those co-benefits on the part of the entity carrying out the project. Within this causal pathway, local co-benefits were more likely to be achieved. In some cases, the World Bank was instrumental in ensuring that there was an explicit and deliberate intent to generate co-benefits at the project design stage, including through its safeguards policies, as noted earlier, specifically those regarding Indigenous peoples; however, the QCA results highlight that this was neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for achieving co-benefits.

Conversely, when there was limited intent to provide project co-benefits, the entity conducting the project felt neither compelled nor committed to serving the community, and the World Bank had limited say in the project beyond ensuring compliance with safeguards, co-benefits were unlikely to be generated (the red boxes in the figure). The results from the case analysis are summarized in table 3.1. Note that table 3.1 summarizes the causal pathways to change as a function of two necessary conditions (intent and commitment), highlighting adherence to those conditions across the cases explored. Furthermore, potential outliers in the analysis are also highlighted, as was the case with Colombia, which did not generate co-benefits despite the presence of both the intent and Bank Group support to do so.

Figure 3.1. Qualitative Comparative Analysis Venn Diagram for Co-benefits

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Colombia 9 is an outlier case in which the causal process broke early on (explaining the lack of co-benefits, despite both intent to provide such benefits and World Bank Group support). PE = project entity.

Table 3.1. Pathways to Co-benefits

|

Positive Outcome |

Negative Outcome |

|

|

Pathways to change |

“Intent and commitment” |

“No intent, no commitment, no pressure” |

|

Boolean expression |

INTENT × PE |

intent × pe × wbg |

|

Groups of cases |

(China 2, China 3, Colombia 10, Colombia 11, Colombia 12) and (Chile 8, Ethiopia 13, Uganda 15, Uganda 16) |

(China 1, China 4, China 5, Chile 6, Chile 7, Uganda 14) |

|

Robustness measures |

Consistency = 1.0 Coverage = 1.0 |

Consistency = 1.0 Coverage = 0.85 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: In Boolean language, expressions in capital letters mean “present,” those in lowercase signify “absent.” Consistency refers to the ratio of the number of cases in which a particular variable (or combination of variables) is present that are successful to the total number of cases in which that particular variable (or combination of variables) is present. It equals 1 when all the cases in which the particular variable (or combination of variables) is present are successful. Coverage refers to the ratio of the number of cases in which a particular variable (or combination of variables) is present to the total number of successful cases. When it equals 1, then the particular variable is not only sufficient but also necessary, for success: it is present in all successful cases.