What is (good) program theory in international development?

There is a lack of consensus on what program theory is about in the development community.

There is a lack of consensus on what program theory is about in the development community.

By: Jos Vaessen

Policy interventions are designed to ultimately benefit citizens, communities, institutions and society as a whole. To better understand how interventions can make a difference, for whom and under what circumstances, it is paramount that we develop useful and realistic abstractions (“theories”) of intervention realities. In a previous blog I identified four symptoms of sub-optimal use of program theory in the design and evaluation of policy interventions in international development. In this blog, I focus on the first symptom, a lack of consensus on what program theory is about. Differences in terminology, a lack of clarity on the sources of theory, and a lack of understanding of (good) theory specification all contribute to this lack of consensus.

In practice, many related terms are used when talking about program theory: theory of change, policy theory, program logic, logic model, intervention logic and logical framework are prominent examples. Although these terms are often used interchangeably, in some cases they mean different things. Funnell and Rogers (2011) present a helpful discussion in this regard.

There is also some confusion regarding the sources of program theory. One can discern three major sources. First, intervention stakeholders (donors, managers, staff, but also implementing partners, beneficiaries, etc.) all have their beliefs and expectations as to how an intervention should and will work. The other two major sources of program theory are substantive academic theory and empirical data (i.e. as a basis for grounded theory). Program theory ultimately should rely on all three sources (Chen, 1990). However, this closely relates to the purposes and uses of program theory in design and evaluation, a point that I will take up in subsequent blogs.

This brings me to the third and most important point, theory specification. To better understand the quality of theory that underlies many development interventions, I distinguish between three levels of program theory specification in ascending order of explanatory power and robustness. This framework is inspired by Toulmin’s (1958) principles for argumentation analysis and Leeuw’s (1991) use of these principles in program theory reconstruction.

To illustrate these three levels I use the example of payments for environmental services (PES), a type of intervention that has received ample support from the World Bank in collaboration with the Global Environment Facility.

The basic premise underlying PES is that different forms of land use have implications for the provision of environmental services such as biodiversity, carbon sequestration (related to climate change) or (ground) water quality and regulation. The problem is that there is usually no market for these environmental services. Consequently, private land users do not have an incentive to invest in land uses that supply them. Offering payments to private land users for the generation of these services intends to overcome this problem.

With this example in mind let us now turn to the three levels of program theory specification.

Level 1: simple successionist causation. Many international development interventions rely on this type of program theory. A simple successionist causal theory is specified as a series of causal steps of the type A leads to B. For example, payments for environmental services provided to farmers (A) leads to farmers changing their land use by introducing land use practices that are more likely to generate environmental services (B). There is usually not much detail to the theory and one is left with a rather limited perspective on causality.

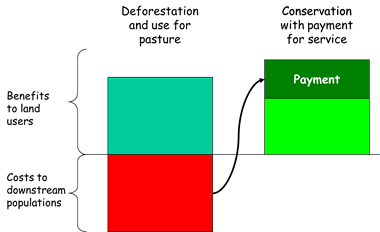

Level 2: successionist causation with warrants. The warrant refers to the why part in the theory. In our example, A is expected to lead to B because adoption of the environmentally more friendly land use practice (i.e. conservation with payment for service, Figure 1) is estimated to be privately more profitable than deforestation, a clear incentive for farmers to adopt the practice. In addition, adoption of the land use practice is also profitable from a societal perspective as long as the premium paid to farmers per unit of land is lower than the costs per unit of land for continuing the more environmentally destructive land use (i.e. deforestation and use for pasture, Figure 1).

Level 3: causation with warrants and causal assumptions. The most detailed level of theory specification provides information on both the warrants and the circumstances in which it is more or less likely for B to occur as a result of A. Let us call the warrant presented above W. In our example, A leads to B, because of W, under certain circumstances (C). For example, C could refer to household-specific constraints in terms of labor or the knowledge needed to apply the land use practices. C could also refer to farmers’ beliefs and attitudes with regard to innovations. The type of causal approach that characterizes a “level 3” theory is the bread and butter of inter alia realist evaluators, who put human agency at the center of evaluative inquiry. Rather than simple successionist causation, the realist perspective relies on the principle of generative causation: what works for whom and under what circumstances (see Pawson and Tilley, 1997; Pawson, 2013). As is the case for the warrants, the causal assumptions can (and should) be vested in (social science) theory (see Vaessen and Leeuw, 2009).

While much of the World Bank’s rich analytical (theory-driven) work on PES can be characterized as “level 3”, this is not typically the case for many other program areas. Both within the World Bank Group and beyond, the bridge between analytical (theory-driven) work and operations can be rather weak and program design and evaluation continue to rely on “level 1” theories. As a result, their value in terms of offering a framework for explanation, sense-making and measurement is rather limited. Specifying the warrants and the contextual variables that relate to the expected causal steps in the program theory, and looking at existing empirical research and substantive theory for inspiration is not only good practice, it is essential for developing truly useful theories that can help us to make sense of complex intervention realities.

In subsequent blogs I will continue the discussion on using program theory in international development.

Chen, H.T. (1990). Theory-driven evaluations. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Funnel, S. and P. Rogers (2011). Purposeful program theory: effective use of theories of change and logic models. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Leeuw, F. L. (1991). Policy theories, knowledge utilization, and evaluation. Knowledge and Policy, 4, 73–92.

Pagiola, S. and G. Platais (2007). Payments for environmental services: from theory to practice. Washington D.C.: World Bank.

Pawson, R. and N. Tilley (1997). Realistic evaluation. London: Sage.

Pawson, R. (2013). The science of evaluation: a realist manifesto. London: Sage.

Toulmin, S. (1958). The uses of argument. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vaessen, J. and F. Leeuw (eds.) (2009) Mind the Gap: Perspectives on policy evaluation and the social sciences. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Using ‘Theories of Change’ in international development (by Jos Vaessen)

How complicated does the (Intervention) Model have to be? (by Jos Vaessen)

Institutionalizing Evaluation: What is the Theory of Change? (by Caroline Heider)

Influencing Change through Evaluation: What is the Theory of Change? (by Caroline Heider)

Comments

Thank you Jos for this blog…

Thank you Jos for this blog series on program theories and sense-making frameworks. A very useful reminder that program theories are not a mere bundle of boxes and arrows. Generative and configurational causation (your level 3) are hard to come by in project documents and evaluations alike. I wonder if in one of your blog posts, you could touch upon the topic of "knowledge accretion" from level 3 program theories. What does it look like? How can we strategically organize evaluation exercises to elicit (and if possible) share them?

Dear Estelle, thank you for…

Dear Estelle, thank you for your comment. Knowledge accumulation and learning across interventions are important ingredients for designing better interventions. I will try to elucidate this (probably) from various angles in future blog posts. A program theory can be reconstructed for a particular intervention in a specific location but can also reflect the combined insights from similar interventions in different settings. In the latter case, the program theory (regarding e.g. under what circumstances is microfinance likely to contribute to women’s empowerment) is continuously refined on the basis of new evidence stemming from individual interventions. Consequently, it is this (higher level) theory that encapsulates some of the learning regarding what works and what does not work under particular circumstances. Thanks again for raising this important point.

Hello Jos,…

Hello Jos,

Very interesting post, as was the first one on this blog. I am looking forward to the next one.

One idea I had in mind while reading it was the fact that there are implicit and explicit theories of change... Part of the planning exercise when setting up an intervention is to make explicit the assumptions on the current situation, on the conditions of success, on the risks, etc... that the implementers may have. This exercise is made a little more easier by RBM tool, logframes, etc... However, we know from social sciences that it is a very difficult and demanding process, from a cognitive as well as from a practical viewpoint, to clarify what one has in mind. However, another issue is that, during the implementation phase, new (or revised) theories of change (assumptions, causality schemes, perceptions of what is possible or not, etc...) appear and are used as references by implementers. And then, comes the evaluator, who has to identify those initial and en-route elements of theories of change... Will you address this topic of implicit / explicit ?

Dear Florent, thanks for…

Dear Florent, thanks for your comment. Indeed, I intend to zoom in on the issue of multiple program theories and the related issue of 'whose theory'. Thanks for making this important point. I look forward to further exchanges.

Dear Jos,…

Dear Jos,

Theoretically you are perfectly right, but is such a 3 level approach realistic for an evaluator on the ground? In fact, usually, evaluators are submitted to harsh time constraints, due to financial ones imposed by the contracting authorities (CAs), with rather tiny presence in the field. More than often the CAs are not even ready to provide all the necessary efforts and means for optimising the evaluation processes. In such a practical context, how can one assume that an evaluator would be able, as per your example, to assess “farmers’ beliefs and attitudes with regard to innovations”? Such beliefs and attitudes are themselves dependent on other factors: level of instruction, spiritual beliefs, gender issues, land property issues, economic reasons, etc. Each factor relying on others it looks quite difficult to take into account all (or even most of) the external factors that could have an influence on the outcomes of a specific project. Working for over 30 years on EU programmes and projects, I think it is fair to say that even such simple tools as the logical framework are of no use in 95% of cases, because poorly designed and rarely including a relevant baseline. So what about when it comes to more complex approaches? Therefore my question: how to apply in daily practice your theoretical approach? If we are able to answer this question in a concrete manner we would have made a great step forward. In any case, I thank you very much for your interesting blog.

Dear Gilbert, thank you for…

Dear Gilbert, thank you for pointing out the practical challenges of developing a nuanced (“level 3”) program theory. I think (and you seem to suggest the same thing) that the major constraint for applying good program theory in practice is of an institutional nature. Having used program theory in a number of evaluations and having seen many good examples of program theory in practice, I would cautiously say that analytical challenges in principle can be dealt with (in one way or another, pending a number of factors). By contrast, time and budget constraints but also the expectations of commissioners that do not necessarily align with attention to analytical depth, are key constraints that inhibit evaluators (or at the least do not provide evaluators with the right incentives) to develop good program theories. Convincing evaluation commissioners to develop ToRs that allow for the analytical space needed to develop better program theories is something that needs more discussion. Thanks for making this point.

Hi Jos: Your approach is…

Hi Jos: Your approach is very articulated and glamorous looking through an academic lens and sense; though, you are very much realistic that "A program theory can be reconstructed for a particular intervention in a specific location but can also reflect the combined insights from similar interventions in different settings". I will quote e.g. addressing psycho social trauma in case of communities in transition through cash-for-work by the UNDP-Pakistan; the approach is globally successful and acceptable too but in case of Pakistan TDPs from one of the war-zone area was totally a wrong approach of an expert from the other part of the world 2014-15. What I am trying to explain that while designing it is a must that emergency be linked to long-term development but interventions be also linked to social taboos. Kindly put on some concrete thoughts for our learning "that the vehicles shall be design in way that have sufficient cushion for fitting in territorial requirements".

Dear Muhammad, you raise an…

Dear Muhammad, you raise an important point. Context specificity is such an important ingredient of good program theory. In the usual simple boxes and arrows approaches to program theory, the particular influence and importance of context are often overlooked. The generalizability of a program theory (i.e. the extent to which it captures in realistic manner the way a particular intervention works (or is expected to work) across contexts) directly depends on the level of detail that is given to context-specific influences on the nature of causal processes and the likelihood that particular causal processes (given certain conditions) may actually occur. The implication is that if contextual conditions significantly change, the causal explanations (should) also change. I will try to further elucidate this issue in subsequent blogs. In sum, you make a key point that is well-taken.

Thank you so much Jos for a…

Thank you so much Jos for a clear presentation of three levels of Program theory specification. We have just completed preparing theory of change and results chain for a biodiversity project. It was a difficult and strenuous task to come up with a logical theory for explaining the team's perception on how the change will take place. Our descriptions draw elements from what you have described above. We have exactly applied the Level 1 specification and articulated some assumptions. But did not describe 'why' the A will lead to B, though implicitly understood. I very much agree that Level three specification is what should be adopted by all Programs. The contexts and beliefs are very much important. We will try to add the missing element in our Theory of Change (ToC) and make them more complete and reliable. Thank you so much for this clarity in a very simple way.

Dear Rajendra, I am glad the…

Dear Rajendra, I am glad the framework is useful to you. Thank you for your feedback.

Who is this guide. Level 2:…

Who is this guide. Level 2: successionist causation with warrants. The warrant refers to the why part in the theory. In our example, A is expected to lead to B because adoption of the environmentally more friendly land use practice (i.e. conservation with payment for service, Figure 1) is estimated to be privately more profitable than deforestation, a clear incentive for farmers to adopt the practice. In addition, adoption of the land use practice is also profitable from a societal perspective as long as the premium paid to farmers per unit of land is lower than the costs per unit of land for continuing the more environmentally destructive land use (i.e. deforestation and use for pasture, Figure 1).

If you are asking what the…

If you are asking what the source of the statement/Figure is, the citation in the reference section of this blog is Pagiola, S. and G. Platais (2007). Payments for environmental services: from theory to practice. Washington D.C.: World Bank.

Add new comment