In Mongolia, the word “rangeland” is synonymous with “homeland.” It is a clue to the importance of rangelands in a country where a quarter of Mongolians are herders, and the wider livestock economy provides sustenance, income, and wealth to nearly half of the population. For many nomadic societies herding is at the core of their life. Around the world, rangelands support the livelihoods, social traditions, and resilience of 500 million people, primarily in low-income countries. Yet the rangelands that these communities rely on for their livelihoods face a combined threat of overexploitation and climate change.

The quickening pace of rangeland degradation in Mongolia is driven by increased livestock numbers and reduced livestock mobility. In a 2018 report, 12% of Mongolian rangelands were heavily degraded and potentially irreversibly damaged, and another 16% would take up to 10 years and significant effort to recover. This continuing trend has been exacerbated by erratic weather patterns associated with climate change. This includes the increasing frequency and duration of extreme events like drought, floods, wildfires and dzuds (severe winter weather disasters that can lead to catastrophic livestock mortality), that are harming both rangelands and herder livelihoods. This dual threat is impacting rangelands around the world, especially in drylands, where most rangelands occur, and where 73% are degraded.

Evolution of livestock sector in Mongolia

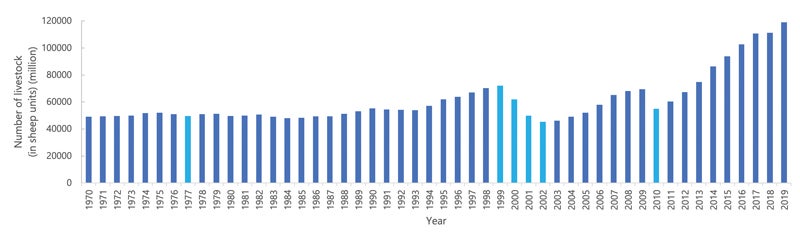

Following liberalization in the 1990s, the livestock sector in Mongolia witnessed a dramatic increase of the national herd size and a change in herd composition in favor of goats (for cashmere). This was coupled with an increasing concentration of livestock in areas close to markets and services, and a decrease in nomadic practices and animal mobility. These changes have also included increased out-of-season grazing, trespassing on reserved pastures, and an associated rise in local conflict.

Note: Light blue bars signify dzud years.

IEG recently conducted an assessment of World Bank support for natural resources management, such as rangelands, to assess the impact of these programs on the vulnerabilities of the millions of resource-dependent people. In addition to supporting livelihoods, rangelands have a vital role to play in mitigating climate change as they are natural carbon sinks, sequestering substantial amounts of atmospheric carbon dioxide in the form of soil organic carbon. In drylands, the soils already store more than one third of the world’s soil carbon, with even higher potential under improved management.

While evaluating the World Bank’s support for addressing the natural resource management and vulnerability nexus, IEG conducted an extensive field assessment in Mongolia. The following lessons emerged from this experience that can help inform future investments in rangelands:

1. Solutions need to be best fit for the local context to ensure sustainable and equitable outcomes

Rangelands are often common pool resources: accessible to everybody, policed by nobody. A common approach to addressing the degradation of common pool resources is to give people individual ownership to increase their incentive to not overexploit the resource. Enclosures (i.e., fencing land and assigning individual plots) were used by the World Bank in Inner Mongolia, China, but this practice had unintended outcomes. In some cases, it increased degradation as restricted herder movement caused continued overgrazing in already overexploited pastures. It also increased inequality as powerful herders managed to claim the best land when it was divided.

This approach fundamentally changed local nomadic culture while yielding disappointing productivity and restoration benefits because it was not aligned with local socio-ecological conditions. In Mongolia, the World Bank instead appropriately used Community-Based Rangeland Management (CBRM). CBRM supports local agreement on livestock mobility and storage-related practices, including seasonal pasture rotation that allows for rest and recovery without fencing. The approach is rooted in adaptive strategies that are traditionally used by Mongolian herders to prepare for and respond to pasture and climatic conditions.

2. Governments need to establish an incentive structure that addresses the drivers of degradation and encourages ecologically responsible behavior

The governance of natural resources such as rangelands remains a challenge globally. In Mongolia there is little governance of the rangelands: there is no institution responsible for pasture management, and implementation of the existing land law is weak. Additionally, until very recently, there was no taxation of the livestock sector, and thus no disincentives against overexploitation. In the absence of incentives for sustainable management of open access rangelands and disincentives against overexploitation, herders are driven to ever-increasing herds to meet their consumption needs.

Extensive interviews in Mongolia found that most herders are aware of pasture degradation, including their own part in it, but they feel the current system leaves them no choice in this tragedy of the commons. They expressed support for a grazing fee or livestock tax, which would incentivize all herders to favor the common good over individual short-term self-interest. Strong institutions at the central and local level, complemented with appropriate governance measures, are crucial to create the incentive structures that help herders make decisions that support healthy rangelands and their own long-term self-interest.

Since July 2021, the Government of Mongolia has implemented a tax on livestock ownership, the revenue of which should be directed to rangeland and livestock management activities. Although a noteworthy development, successfully implementing and enforcing this law will require substantial political will and local governance capacity. As of now, it is too early to tell whether it will prove effective in incentivizing smaller herds and facilitating rangeland recovery.

3. Markets must be reshaped to put a premium on quality over quantity to support both rangeland health and improved livelihoods

In developing countries, and especially among nomadic herders, livestock supply chains are fraught with technical challenges in meeting basic quality, animal health, and sanitation standards. In Mongolia, as elsewhere, this undermines market access, including export potential. Specifically, the livestock sector suffers from unpredictable trade policies when China closes its border to Mongolian livestock products for fear of livestock diseases.

Without access to markets that place a premium on quality, demand is lacking for the high-quality or sustainably produced livestock products that could incentivize better livestock management and smaller herds. This in turn traps poor herder households in a low investment, low productivity, and low-income cycle. Therefore, value chain approaches that address market access, trade facilitation, livestock extension services, and price-quality relationships, are a key part of protecting rangelands and improving livelihoods.

Rangelands are currently neglected in the growing global restoration agenda, yet they are a major store of carbon and offer great possibilities for achieving both environment and development goals. By addressing the local incentive structures, markets and socio-cultural practices through the use of best fit solutions, which are also adapted to local socio-ecological conditions, rangeland regeneration and the protection of local livelihoods can go hand-in-hand to achieve development, biodiversity and climate outcomes.

Sources can be found in the corresponding sections of the assessment of World Bank support for natural resources management.

Note: On Nov. 17, 2021, the blog was edited to include a link to a 2018 report, as well as to provide an update about a tax on livestock ownership implemented in July of 2021.

Pictured at top: Jalamchagna Dolgoon, 30, and his friends rest while their cows drink at a water pump in the countryside surrounding Khairkhandulan Photo Credit: DAWNING, Rafe H. Andrews, Raul Roman

Comments

This report has outdated…

This report has outdated information and didn't cover fully what is happening in Mongolia and what efforts have been made by national stakeholders including herders themselves to preserve their rangelands. All these work in the past has left important lessons learned and what works and what doesn't work in Mongolia? At least you should read two national rangeland health assessment reports released in 2015 and also in 2017. On top recently first national grazing impact was also released. Parliament of Mongolia approved Animal Number Taxation law which put into effect since 1July 2021!

Dear Ts. Enkh-Amgalan, thank…

Dear Ts. Enkh-Amgalan, thank you for your feedback. The blog has been updated to reflect the recent implementation of the Animal Number Taxation law. We have benefited from the two national rangeland health assessment reports and cite the one published in 2018. Indeed, many valuable lessons have been learned over the last 20 years in Mongolia on what works and doesn't work, which can also inform similar interventions in other countries. Our blog aims to highlight three of these higher-level lessons. Thanks again for reading.

Add new comment