The World Bank Group in Papua New Guinea, 2008-23

Chapter 3 | Performance and Implementation of World Bank Group Strategies

Highlights

Performance has improved although from a low level. Throughout the evaluation period, greater realism was needed about what could be achieved and measured during a strategy period, considering limited state capacity. Strategy implementation was challenging because of weak government capacity for financial and contract management, procurement, auditing, safeguards in central or implementing agencies, and insufficient counterpart funding. Some of the World Bank’s approaches have also overcomplicated engagement and overwhelmed client capacity, especially those associated with introducing international best practices, and so has switching approaches too often, including in response to changing corporate priorities.

The World Bank Group has overcome engagement challenges by increasingly adapting to the country context. The World Bank increased technical staff presence significantly in ways that potentially allow programs to be grounded better in an understanding of context and the client. More effective support has been associated with high-frequency, low-intensity engagement by layering advice and support, not going too quickly, and never letting the engagement cool. This includes staff efforts to build personal relationships over time with clients in ways that help staff navigate patronage dynamics and identify appropriate entry points. Layering institutional analyses and technical fixes to address patronage dynamics over time, such as using performance-based approaches in the road sector, is showing promise. Other efforts featuring low-frequency, high-intensity support provided in short bursts have been less effective.

Other key challenges that continue to undermine the Bank Group effectiveness require additional reflection and adaptation. The high cost of operating in Papua New Guinea has affected engagement and supervision capabilities negatively, and solutions to navigate this constraint more effectively do not appear to be forthcoming. The short duration of postings for international technical staff (because of the fragility, conflict, and violence nature of the environment) has limited opportunities for staff to build client relationships to support medium- to longer-term reforms. Using a regional hub has provided important continuity in some cases.

Overall Strategy Performance

Performance of the World Bank–supported portfolio improved although from a low level. The Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) rated the overall development outcome for implementation of the strategy for FY08–12 as unsatisfactory. The CAS portfolio was slow to become operational: advisory services and analytics delivery experienced delays, and most lending operations were not approved until FY11—three years after the strategy launch. IEG noted that this initial program required greater realism about what could be achieved and measured in a single strategy period. IEG rated the development outcome for the FY13–16 period as moderately unsatisfactory. It recognized progress on roads, telecommunications, agriculture, youth training and employment, the modest progress made on extractives management, access to credit, and the efficiency of opening a business but noted the negligible progress on access to energy or water or debt sustainability. IEG also determined that Papua New Guinea’s economic volatility and limited state capacity had not been adequately factored into the FY13–16 strategy. The strategy was based on an overoptimistic macroeconomic outlook, whereas conditions suffered from adverse commodity price shocks after 2014, affecting the country’s financial capacity to fund projects. Collaboration between the World Bank and IFC was also very limited.

Papua New Guinea’s limited institutional capacity has affected implementation. Weak capacity for financial and contract management, procurement, auditing, and safeguards in central or implementing agencies, along with insufficient counterpart funding, has at times affected implementation throughout the evaluation period.

The Bank Group has and continues to try to overcome some of these implementation challenges by adapting to the country context:

- Effective implementation support has been associated with high-frequency, low-intensity engagement (efforts likened to “lacquering a bowl”) by layering advice and support, not going too quickly, and never letting the engagement cool. This includes staff efforts to build personal relationships over time with clients in ways that help staff navigate patronage dynamics and identify appropriate entry points. Other efforts featuring low-frequency, high-intensity support provided in short bursts have been less effective (see discussions on factors of success and failure across sectors in chapters 4–6).

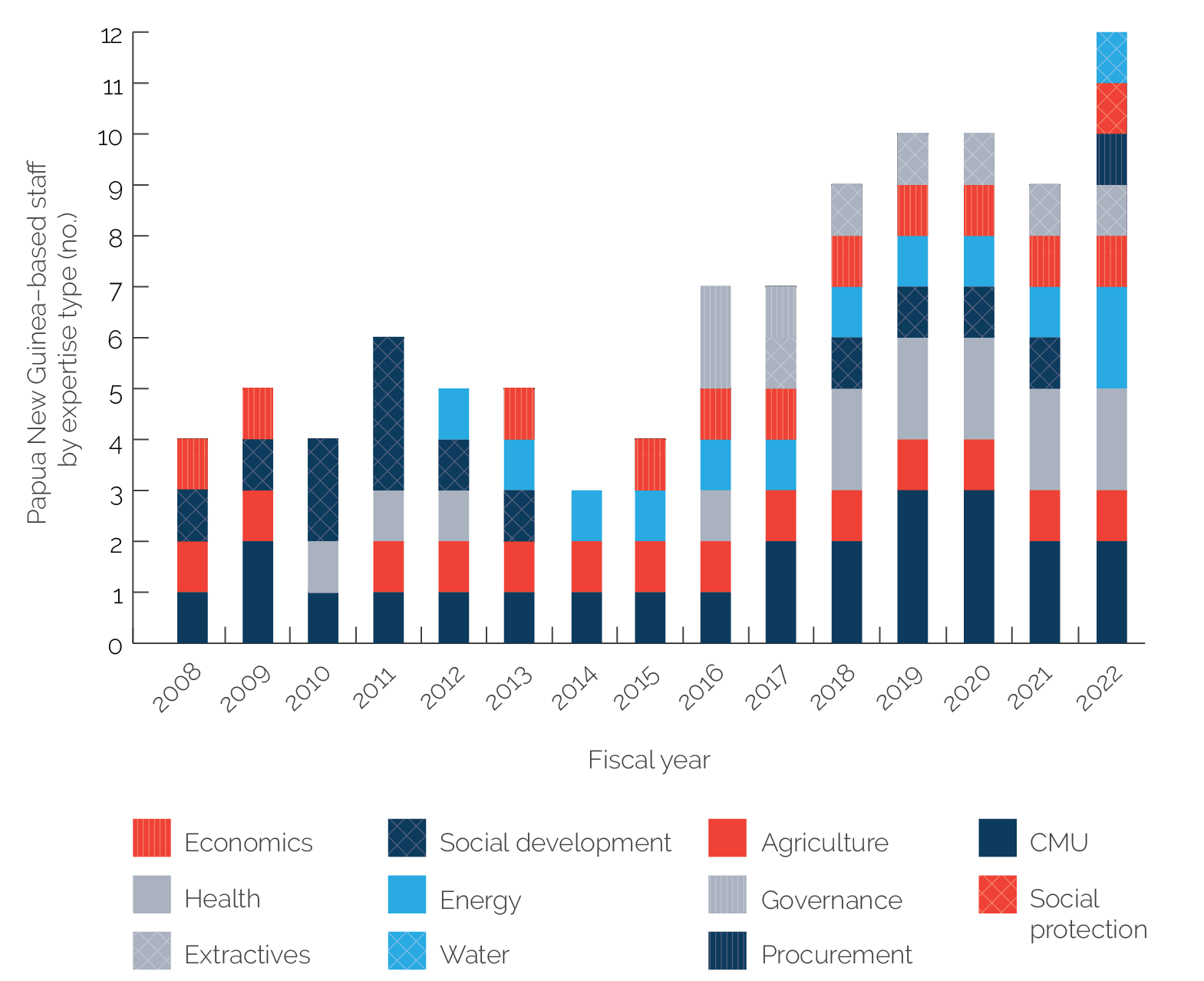

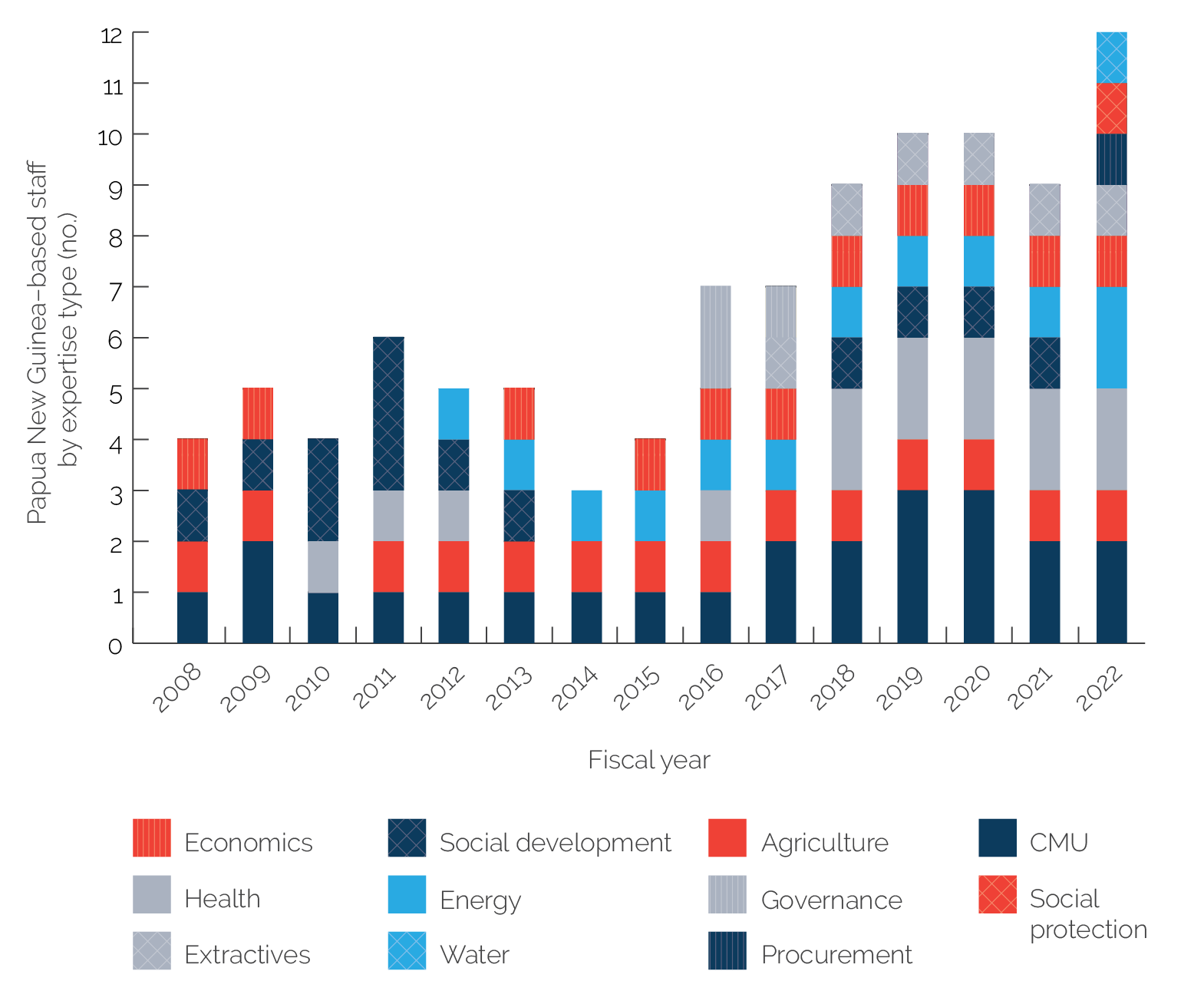

- The World Bank increased technical staff presence significantly in the region and country in ways that potentially allow programs to be grounded better in an understanding of context and the client (figure 3.1). For example, the resident mission maintained modest staffing during the first half of the evaluation period (including a country manager, an internationally recruited economist, and local operations officers), but it has recruited several international and local technical experts in the country, including through using extended-term consultants.

Figure 3.1. World Bank Specialist Staff Operating out of Resident Mission, by Area of Expertise

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: This figure shows only (grade level) GF+ technical specialist staff, thus excluding corporate functions (such as country security specialist, External Affairs/External and Corporate Relations, or GE level staff, or technical extended-term consultants). CMU = Country Management Unit.

- The World Bank applied a political economy lens to improve the design and targeting of certain sector engagements and enhance performance in the latest strategy period. Political economy analysis has been undertaken by several teams since the CPF launch in 2019. The effort to increase political economy analysis is part of the Bank Group’s response to its CPF commitment to have project design and implementation informed by deeper political economy analysis. Governance specialists have worked with Human Development teams to develop mechanisms to improve targeting through enhanced subnational implementation arrangements. For example, Human Development teams used institutional assessments conducted by the Governance Global Practice to redirect some of the child nutrition activities away from the district level toward the provincial level to attempt to shield these activities from political interests. As the analyses suggested, provincial health authorities have more potential to deliver services effectively based on their mandate, capabilities, and incentives, compared with the national or district levels that were highly influenced by political interests and pressures to redirect resources to patrons. Before the recent period, the Bank Group did not use political economy analysis to address institutional and sector challenges.

Other implementation challenges have and continue to be harder to overcome given the country context, including the following:

- A shift in the World Bank’s approaches has sometimes overcomplicated engagement with the authorities and risked overwhelming client capacity. The ability of local institutions to adapt to new program requirements needs to be weighed against the World Bank’s proclivity to introduce new approaches that have worked elsewhere globally or that respond to corporate or sector priority setting. For example, the World Bank has supported four different program designs in the agriculture sector in Papua New Guinea over the past decade, each focused on a different or expanded set of commodities or livestock and each with new program requirements. Interviews with the World Bank and the government attest to the difficulty of effectively engaging new commodity boards (that are also highly political), building new implementation arrangements subnationally, and communicating new program expectations to lead farmer partners and agricultural communities. Other examples include the introduction of CDD concepts and tourism activities that worked in the region but that were not sufficiently adapted to Papua New Guinea’s low level of subnational governance and implementation capacity.

- The high cost of doing business in Papua New Guinea, in part because of security constraints, has affected engagement and supervision capabilities negatively. The number of suitable private security companies in the country is limited, and unlike in some other FCV countries, the UN does not provide security assistance to World Bank missions. Security threats are also multifold and diffuse. Multiple staff and visiting missions have provided data on the cost of doing business in the country related to security costs. Although every country has a unique set of risks associated with a unique set of conflict and violence drivers, the security risks in Papua New Guinea are undermining staff’s ability to comprehensively support their projects subnationally. The lack of a corporate-wide gathering or analysis of supervision-related security costs limits an assessment of comparators.

- The short duration of internationally recruited staff technical postings (because of the FCV posting, including rest and recuperation or time out of country) limits opportunities for these staff to build client relationships to support medium- to longer-term reforms. Based on an analysis of human resources data, the average duration of an international staff technical posting in Papua New Guinea (between 2008 and present) is two years,1 because of its FCV nature, and time in country is even less because internationally recruited staff are given time off and resources to leave the country for rest and recuperation. Long-standing locally recruited staff in certain sectors that have nurtured their client relationships have helped overcome some implementation challenges but are not alone sufficient to mitigate significant delays.

- A lack of continuity in IFC’s staffing presence affected deal flow, which decreased when IFC resident representatives and investment staff were not based in the country. In the early part of the evaluation period, the appointment of a former banking executive from the region to the position of country coordinator and resident representative helped increase IFC’s footprint by staffing the office (including with an associate investment officer) and by using their extensive networks to develop multiple advisory activities and financial sector investments. The resident representative held the position for several years (2009–15), after which in-country staffing was reduced significantly. During this middle period (2016–17), few advisory activities and almost no investment activities took place. The COVID-19 crisis (2020–22) further undermined efforts to reinvigorate the investment program. Over the past two years, IFC has put a resident representative with FCV experience in place and brought significant skills to the country in agribusiness, the financial sector, and gender, but investments have been slow to materialize. Nevertheless, a renewed focus on relationship building holds expectations that opportunities will materialize.

- IFC advisory services, supported by external donors, faced disbursement pressures and had ambitious objectives that were met due to country capacity constraints, especially in the agribusiness, telecommunications, and private sector industry areas. IFC has faced challenges in cultivating client relationships—a factor exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Until 2023, disbursement ratios remained low.

- Time series data on basic staff characteristics (job title, internationally recruited staff, locally recruited staff, and so on) for all staff with duty station in Papua New Guinea as of June 30 for fiscal year (FY)08 through FY22 were collected from the People and Culture Vice Presidential Unit (that is, fiscal year end snapshots). The evaluation team categorized staff as being Country Management Unit or technical based on their job titles and other information. These data were used to calculate average duration of (grade level) GF+ technical and Country Management Unit staff posted in Papua New Guinea during the evaluation period FY08–22. Based on these calculations, the average time spent by the staff in the country during the evaluation period is two years for technical staff and three years for Country Management Unit staff. International Finance Corporation staff, GE and lower grades, short-term consultants, extended-term consultants, and “corner cases” (that is, staff who were only in Papua New Guinea during FY08 or FY22, the two end points of the evaluation period) were excluded from the calculation of the average duration.