The World Bank Group in Papua New Guinea, 2008-23

Chapter 2 | Evolution of World Bank Group–Supported Strategies

Highlights

World Bank Group–supported country strategies have relevantly evolved to cover major development constraints by staying engaged in core sectors where results have been achieved while nurturing new sector relationships (including through analytics) and by focusing more on governance and institutions to address development gaps, as identified in the Systematic Country Diagnostic.

The World Bank has increasingly leveraged its multilateral position and technical expertise to achieve more meaningful complementarities with partners. Reflecting its status as a relatively minor development partner for Papua New Guinea in financial terms, the Bank Group’s role evolved from one focused on delivering services in core sectors (such as transport and agriculture) to leading by demonstrating innovative technical approaches that others are replicating and by leveraging co-financing to achieve complementary donor aims.

Decisions on the scope of Bank Group engagement have not always been based on an assessment of what is feasible in the Papua New Guinea context. To achieve country strategy objectives, a better sense of realism was needed about what could be achieved, considering limited state capacity. The International Finance Corporation’s engagement involved relevant advisory services and investments, especially the rollout of information and communication technology infrastructure in underserviced areas, but its country strategy depended heavily on reforms that exceeded reform capacity.

Data scarcity has been a major constraint in setting feasible and measurable objectives and in determining scope, and it has undermined planning, targeting, prioritizing, policy development, monitoring, and evaluation. Bank Group strategies did not sufficiently prioritize addressing this constraint.

The Bank Group relevantly pursued a pragmatic approach to gender that focused on the economic justification for gender equality. The International Finance Corporation also relevantly and effectively demonstrated the business case for addressing gender-based violence.

Country strategies have included fragility, conflict, and violence considerations, but the Bank Group’s approach gained relevance by drawing on analytics that identified the need to understand and address the interrelated risks posed by fragility, disaster, and climate change. Despite these efforts, disaster risk reduction and climate change issues were underprioritized during most of the evaluation period.

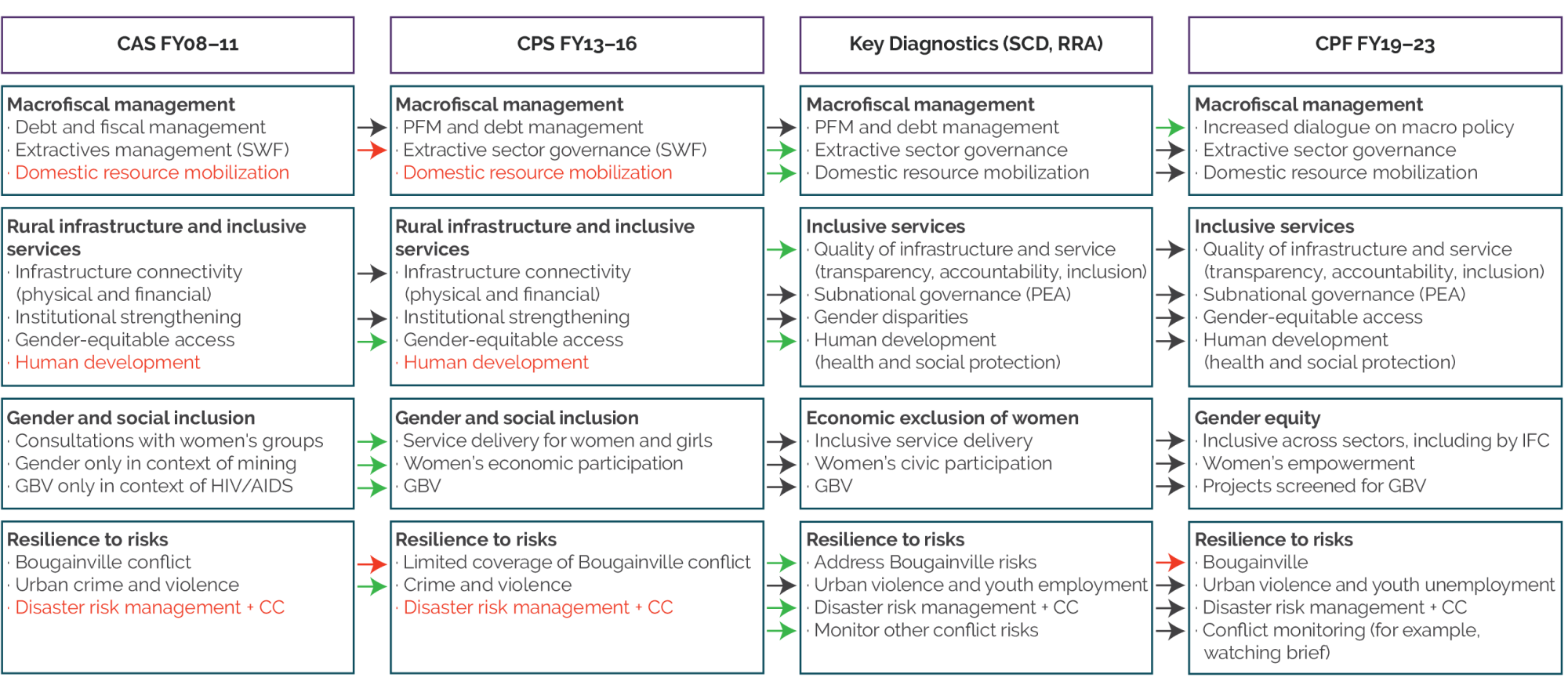

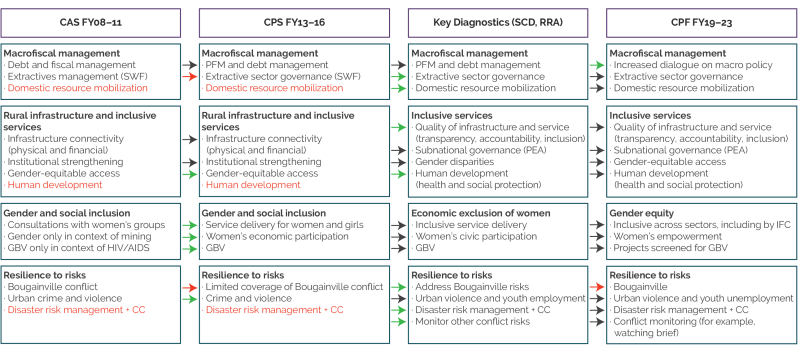

This chapter discusses the evolution of the Bank Group–supported strategies in line with changing priorities and considering key diagnostics. The chapter covers the CAS for FY08–11, the CPS for FY13–16, the CPF for FY19–23, and the IFC Country Strategy for FY19–23. It considers how the changing context and key analytics such as the FY18 SCD and the FY18 Risk and Resilience Assessment (RRA) informed these strategies. Figure 2.4 maps the evolution of strategic priorities.

A strained relationship between the Bank Group and the government made it difficult for the Bank Group to engage in Papua New Guinea effectively before the evaluation period. Government attention to development effectiveness was limited between the early 2000s and 2008. Government noncompliance with a World Bank–supported forestry operation (among other complications) resulted in suspension of the operation, a breakdown in World Bank–client relations, and cessation of all new lending between 2003 and 2007. Nevertheless, the World Bank maintained a country presence through an Interim Strategy Note that included ongoing transport activities and selected analytical work while assessing alternative delivery mechanisms (for example, community-driven approaches) to improve implementation.

The Reengagement Period

The World Bank made considerable efforts to rebuild trust and reestablish entry points during the first CAS (2008–13), or reengagement period. Finding reentry points was challenging because the World Bank had very little financing to offer compared with other donors. The Bank Group remained a relatively small donor throughout the evaluation period, providing about 9 percent of international development assistance. The Australian government and the Asian Development Bank together provided 70 percent over the same period. The government of Papua New Guinea also receives significant grant financing from bilateral donors, especially Australia. The World Bank did not undertake joint strategy development with other donors during the reengagement period. The government viewed donor coordination as threatening at the time, with donors being accused of “ganging up,” ultimately upending initiatives (World Bank 2007).

The World Bank rebuilt its country engagement by focusing on core infrastructure in sectors where it could generate goodwill and had long-standing engagements, especially in transport and agriculture. It did so along with other donors that were also supporting transport projects, for example, by working in different geographic zones. The World Bank built on its long-standing engagement in the transport sector to support the second phase of a road program focused primarily on sections of the Hiritano Highway, which connects the capital to a secondary city in the Gulf of Papua region, whereas the Asian Development Bank focused primarily on rehabilitating the Highlands Highway, for example. The World Bank also supported a smallholder oil palm development project, leveraging its background in the sector, and focused on supporting improving production in existing cultivated areas and rehabilitating smallholder access roads. Although oil palm development is controversial, the program ensured that no new oil palm trees were planted in new areas. Besides being a large source of export revenue, oil palm contributes to smallholder incomes significantly.1

Despite being a relatively small player, the Bank Group’s role in relation to other key donors has evolved from one focused on delivering services (in parallel with others) toward leveraging its multilateral position and global technical expertise to achieve more meaningful complementarities and replication effects. The World Bank had difficulty finding entry points early in its engagement, but it has increasingly used innovative technical approaches to overcome institutional bottlenecks, thus stimulating replication or engendering more meaningful collaboration (including co-finance) in agriculture (through a productive partnership model), transport (through performance-based contracts), and health (by engaging subnationally) to amplify impact (see chapter 3).

During this period, the World Bank also focused on the residual drivers of conflict in the Bougainville region and conflict risks in other mining areas but left other risks unaddressed. The World Bank focused on addressing grievances associated with the use of mining resources by supporting local economic development in postconflict Bougainville. It relevantly used a community-driven development (CDD) approach implemented through women’s groups, thus also supporting the fragile social capital that emerged from the warring period. In addition, the strategy focused broadly on enhancing natural resource governance, supporting the development of a sovereign wealth fund for mining that could also be used to help manage prospective liquefied natural gas (LNG) revenues. Other significant risks to sustaining development outcomes, such as disaster risks and climate change, were left unaddressed.

The World Bank engaged cautiously on gender issues during the early strategy period as it worked to regain trust and rebuild its relationship. The World Bank framed gender equality largely in relation to social inclusion (limiting its focus to women in mining primarily). GBV was referenced only in relation to HIV/AIDS. During this strategy period, it was also sensed that the national dialogue had not advanced enough to allow the World Bank to propel reforms in the gender space.

The FY13–16 Country Partnership Strategy Period

The CPS for FY13–16, largely a continuation of the previous engagement strategy, was overoptimistic about Papua New Guinea’s economic trajectory. LNG exploitation constituted a major investment in Papua New Guinea, estimated at approximately $17 billion, or more than double Papua New Guinea’s annual GDP. The World Bank’s 2010 CAS Progress Report focused on the associated growth and revenue opportunities. The CPS for FY13–16 predicted an aggregate GDP expansion of 25 percent as the LNG project moved to full production, while noting that expectations about transformational gains in welfare and employment should be tempered somewhat. But sector and economic risks were not considered adequately—commodity prices (including for LNG) had been declining since 2012, and challenges with sector governance and taxation were well known. By 2016, GDP growth receded. A profit-based royalty regime and generous capital allowance negated any tax benefits, leaving a sizable hole in the government’s finances (World Bank 2018a).

The Bank Group took a pragmatic approach to gender and a more expansive view of fragility, conflict, and violence (FCV) during this period. The CPS for FY13–16 applied a pragmatic approach to gender by addressing the underlying economic justification for gender integration both in society and at the communal and household levels. IFC advisory services played a strong role in making the business case for gender equality and addressing GBV. The CPS amplified FCV issues by expanding its reach to conflict-affected areas outside of Bougainville and by continuing to work on mining sector governance. During this period, diagnostics and investment in youth employment increased the attention to crime and violence issues. Disaster risk management and climate change resilience were again left unaddressed.

Country strategies before FY19 paid limited attention to human capital development. Papua New Guinea, like other clients in the region, preferred borrowing for infrastructure because of the blended or International Bank for Reconstruction and Development lending terms offered by the World Bank. That—together with support from other donors, limited staffing, and the World Bank’s need to find common ground with the government—explains the historical lack of focus on human development issues (see figure 2.4). Other entry points, such as focusing on domestic food production as part of a health and nutrition strategy, were slow to become operational. The World Bank focused primarily on cash crops before its FY19 strategy, although additional financing for the Productive Partnerships in Agriculture Project (PPAP) supported a small nutrition intervention pilot focused on education and training. The follow-on agriculture project (Agricultural Competitiveness and Diversification Project) will increase nutrition interventions, including improving targeting and delivery mechanisms through diagnostics and institutional capacity building and diversifying household crop production. Historically, the government was also averse to the concept of social protection.

The 2019–23 Country Partnership Framework Period

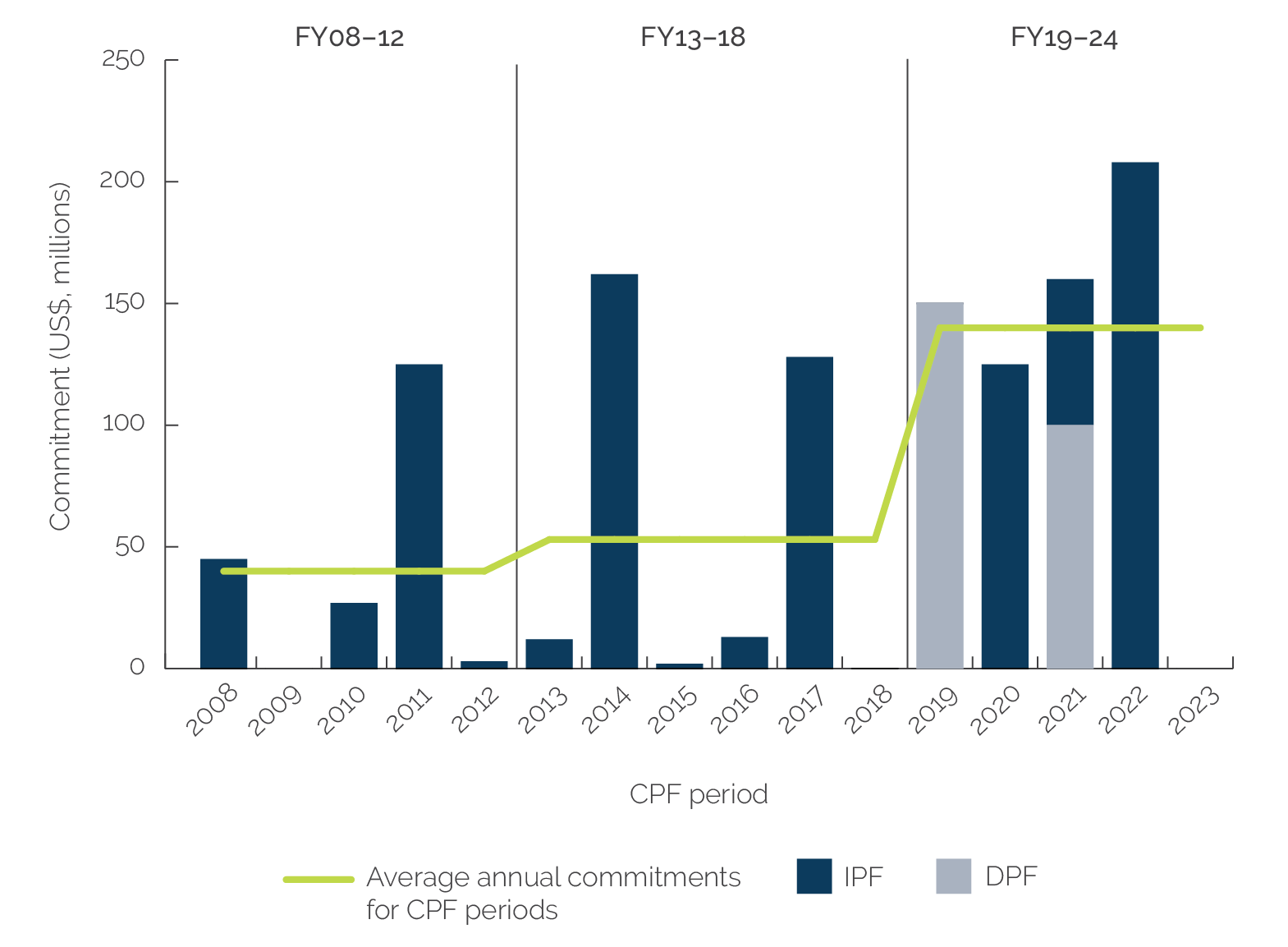

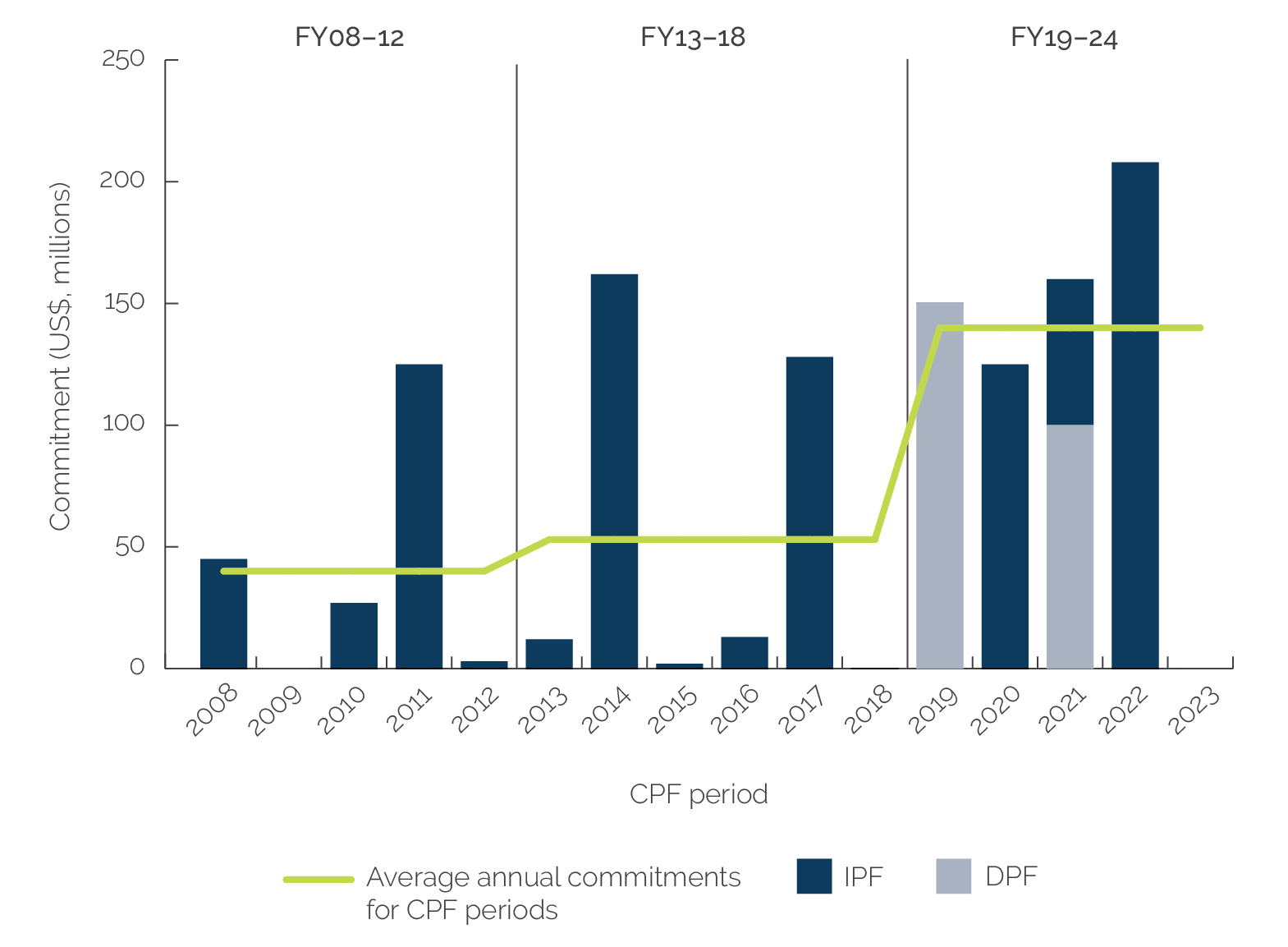

The World Bank has rapidly increased its financial assistance to Papua New Guinea as part of a wider effort to provide increased financial support to the Pacific region. Average annual World Bank commitments during the current strategy period ($140 million) were almost four times greater than the earliest period under review ($40 million), with greater lending volumes attributable to the preponement of the 20th Replenishment of the International Development Association (IDA) for the global pandemic response and increasing IDA’s levels for FCV (figure 2.1). The introduction of budget support during this latter strategy period (that accounted for 39 percent of all lending during this period) was notable. This increase mirrored trends in the region whereby the World Bank multiplied its support six times over the past decade, mostly through expanded concessional credits from IDA.

Figure 2.1. Annual World Bank Commitments, FY08–23

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: CPF = Country Partnership Framework; DPF = development policy financing; FY = fiscal year; IPF = investment project financing.

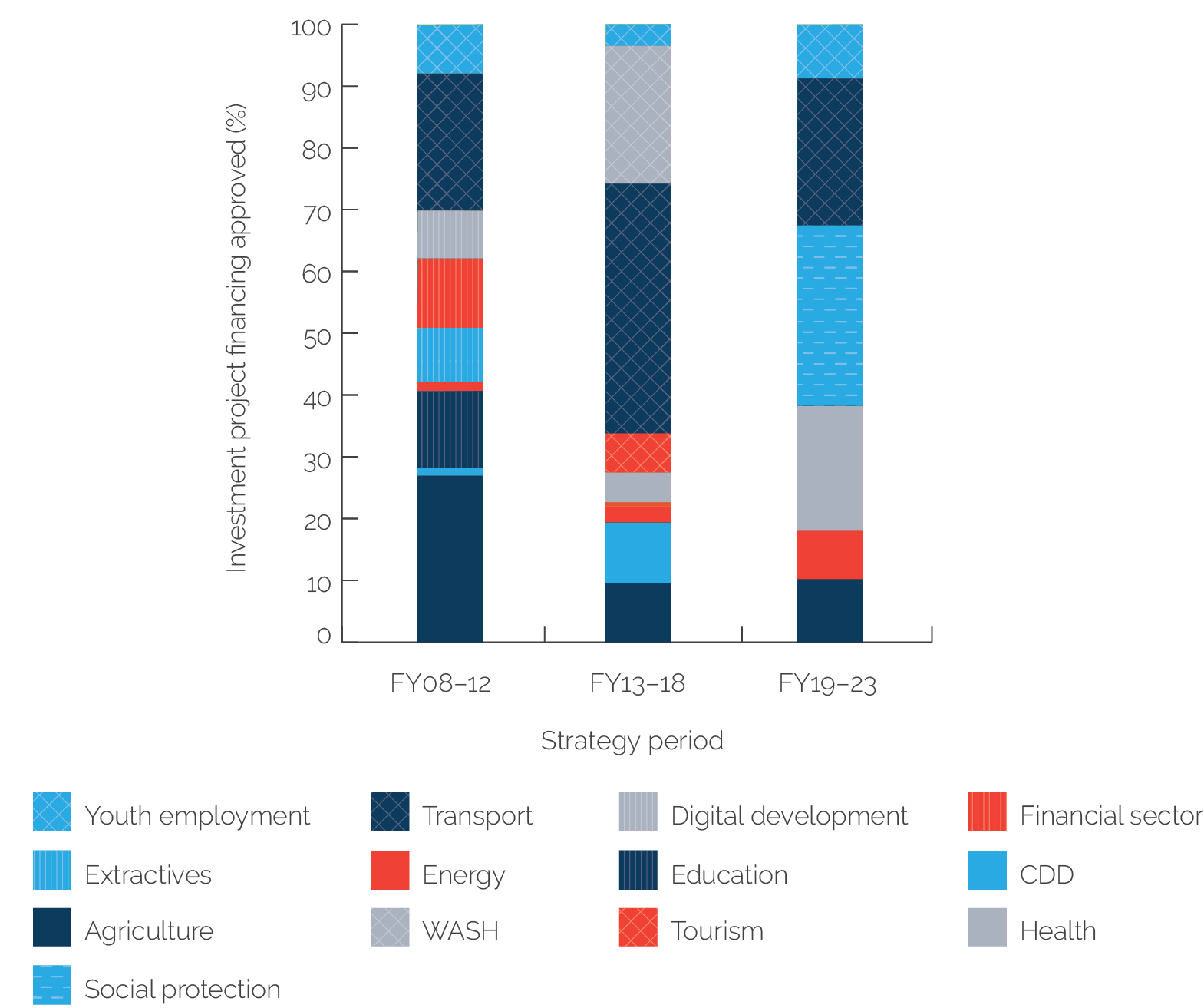

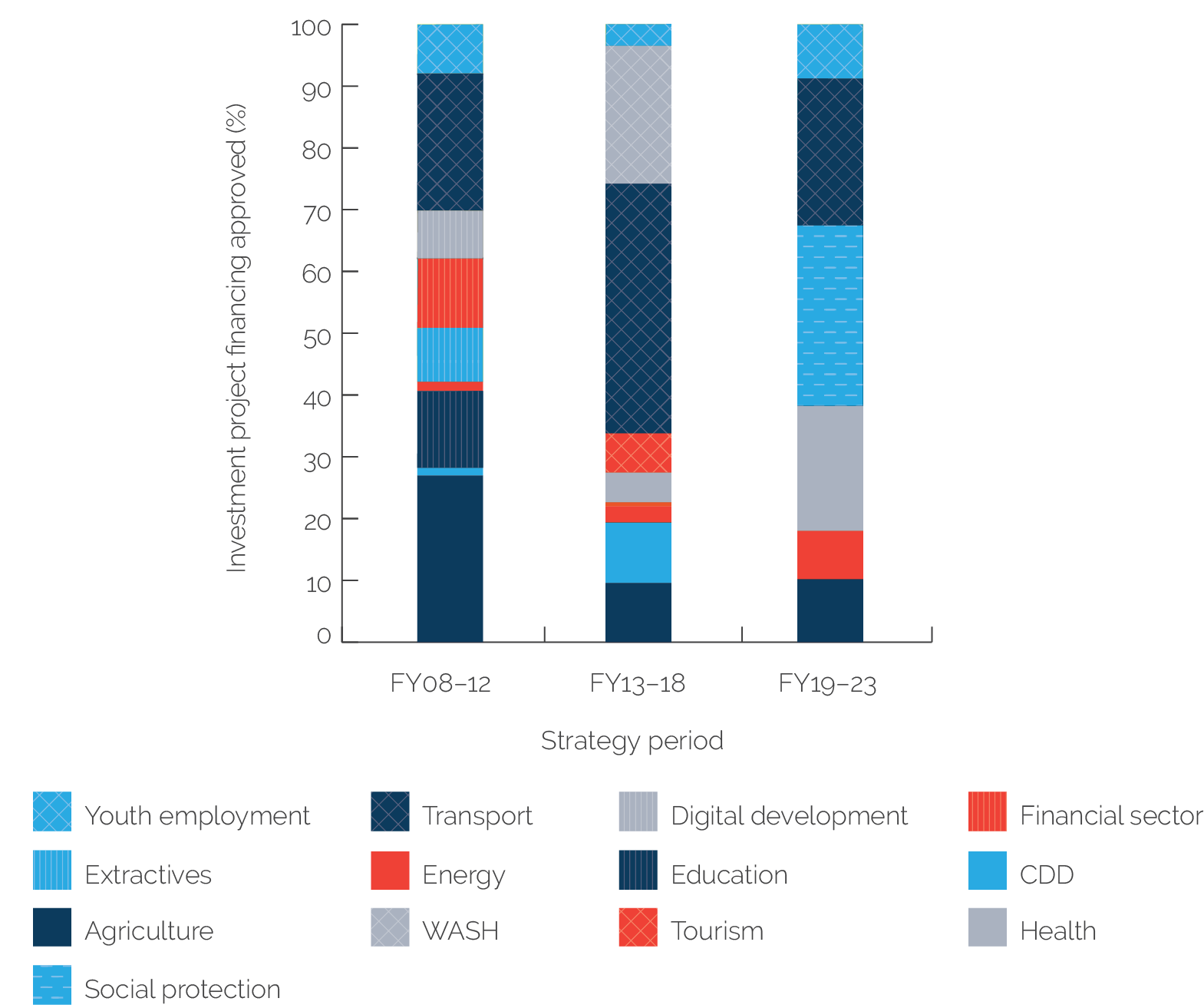

The 2019–23 CPF period consolidates activities across core sectors by building on long-standing relationships while taking risks by engaging in new sectors to address key development constraints. Investment project approvals have notably been concentrated in fewer sectors—from nine sectors during both the CAS and CPS periods to six sectors in the CPF period (figure 2.2). The World Bank has maintained its involvement in the transport and agriculture sectors, including through new investment projects (figure 2.2). More recently, it has also taken risks by engaging in sectors where it lacks established relationships (such as in health and social protection) to address key development challenges identified in the SCD. The World Bank’s support in these areas fills coverage gaps but also risks overwhelming client capacity—a risk that must be managed carefully (box 2.1). Development policy lending was introduced in this period for the first time in more than two decades to support macroeconomic reforms, but inadequate risk analyses marked this decision (see chapter 4).

Box 2.1. Taking Risks to Address Key Development Challenges in Papua New Guinea

The decision to simultaneously run multiple human development projects in the latest Country Program Evaluation period, although aligned with Papua New Guinea’s human development challenges, risks stretching client absorptive capacity. The simultaneous development of multiple human development investment projects reflected the need to respond to COVID-19, expand the tuberculosis program, and strengthen health systems, especially to address malnutrition and stunted growth in children. However, this has placed a heavy burden on the country’s Department of Health, which before fiscal year 2017 had no previous experience implementing World Bank investment projects. Previously, other donors provided much of the support for human development through grant mechanisms. The World Bank’s new lending involves new modalities to improve service delivery that are being tested for the first time, such as disbursement-linked indicators and cash transfers. Multiple interviews confirm that although the engagement is highly relevant, it must deliver results, or the client may choose not to borrow from the World Bank again for this critical development need. Implementation status reports point to challenges associated with the complexity of program design. Overall implementation progress in the latest Implementation Status and Results Reports has been rated moderately unsatisfactory for two of the active health projects.

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group; World Bank 2023a, 2023b.

Evidence shows that the World Bank’s most recent engagement strategy is poised to leverage complementarities to achieve impact at scale. In the latest strategy period, the World Bank partnered with the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) in the health sector to support the Fast-Track Initiative to Reduce Stunting. DFAT is co-financing programmatic advisory services and analytics and an investment operation with the goal of achieving more economies of scale at the sector level. Similarly, a recently approved World Bank transport project leverages Australian co-financing of $15 million to improve the focus on maintenance and rehabilitation that improves climate resilience (of portions of the Ramu and Hiritano highways), including helping build the capacity of the road sector.

Figure 2.2. Investment Project Financing Approved by Sector across Strategy Periods, FY08–23

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: CDD = community-driven development; FY = fiscal year; WASH = water, sanitation, and hygiene.

The need to improve governance and institutions and subnational engagement—prominent themes of the 2018 RRA and the SCD—are a focus of the CPF for FY19–23. Addressing governance and institutional challenges is a cross-cutting theme in the CPF, drawing on the RRA recommendation to work with subnational governance structures in supporting service delivery improvements. The RRA made a case for mainstreaming political economy analysis across sector engagements, in line with the SCD’s finding that political economy knowledge constitutes a key knowledge gap in designing and implementing effective programs. Previously, political economy analyses were infrequent or drew from other donors’ work (for example, in the transport sector).

The CPF made the strongest commitments yet toward addressing conflict drivers and mainstreaming disaster and climate resilience (see figure 2.4). The RRA (which informed the SCD) underpinned the need to address conflict, violence, disaster, and climatic risks—interrelated and compounded risks that undermine development effectiveness. The SCD and the RRA reinforced the need to increase focus on gender equality and to address GBV directly as an integral part of the Bank Group’s strategies. The CPF committed to maintain a “watching brief” to support a risk-informed approach to portfolio decision-making and engagement decisions. The idea maintaining a watching brief was developed after the 2019 national referendum that resulted in a near unanimous vote for independence for the Autonomous Region of Bougainville and increasing violence in the resource-rich Southern Highlands. In response to a lack of traction and client demand on disaster reduction and recovery, combined with the impact of a 2018 7.5 magnitude earthquake and its resulting tensions, the World Bank produced a disaster reduction and recovery diagnostic report and an investment plan.

Gender also emerged as a prominent theme. Gender equality was a key theme in the CPF that committed to exploring ways to go beyond a “strictly project-based” approach. The CPF also laid out its commitment to screen all projects for GBV risks.

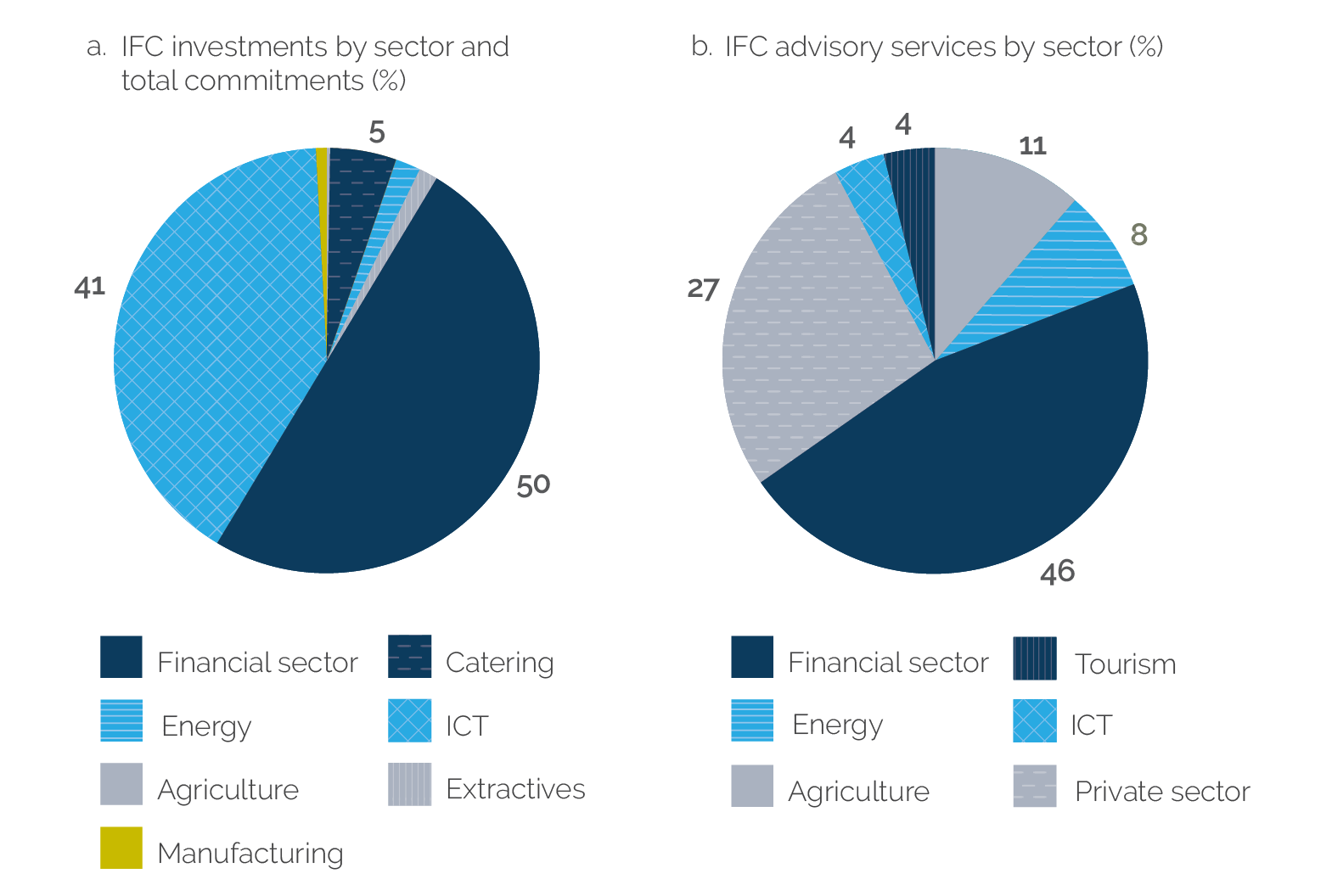

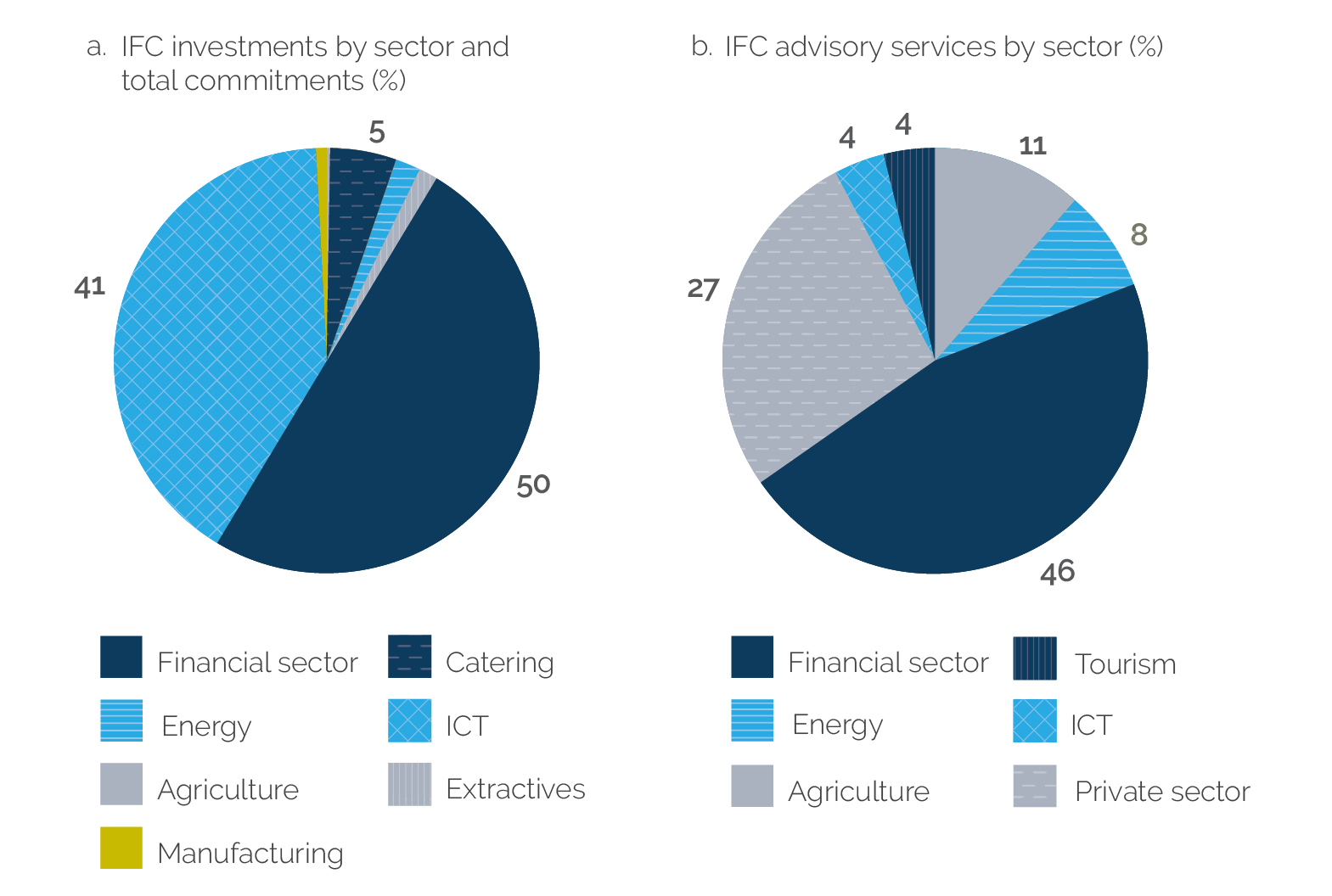

IFC’s engagement across strategy periods involved relevant investment and advisory services. During the evaluation period, IFC’s investment and advisory portfolio consisted mainly of support for information and communication technology (ICT) expansion and financial services, as depicted in figure 2.3. Mobile penetration in Papua New Guinea is estimated to have been 1.6 percent in 2006, and it increased to 35 percent in 2015. Financial sector activities were also greatly needed: Papua New Guinea has one of the least developed financial markets in the region, one in which accessing financing is most difficult (the ratio of private sector credit to GDP is one of the lowest in the world). IFC also contributed positively to developing a credit reporting framework, helped implement a small business tax, put an electronic payment system in place, and contributed to the adoption of a national biosecurity policy. In the energy sector, IFC has also contributed to expanding access to solar power and phone charging through the Lighting Papua New Guinea program and is engaged in discussions on energy reforms.

Figure 2.3. International Finance Corporation Investments and Advisory Services by Sector and Total Commitments

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: ICT = information and communication technology; IFC = International Finance Corporation.

IFC introduced a 2019 Country Strategy that depended heavily on reforms that exceeded the country’s reform capacity. IFC Country Strategies are designed to elevate private sector support ambition under different scenarios of reform pathways. The IFC Papua New Guinea Country Strategy sought to capitalize on the resource sector to boost investment in private sector activities, with agriculture, financial inclusion, and sustainable energy as key focal points, along with gender issues. IFC identified 9 reforms in a low-reform scenario that would allow it to mobilize $245 million and 19 reforms in a high-reform scenario that would enable $400 million. Without reforms, IFC predicted that only $150 million would materialize, as during the previous strategy period. Indeed, in the case of Papua New Guinea, only some of the reforms under low-medium scenario were achieved. IFC was candid about the risks inherent in achieving impact, but its strategy relied too much on the World Bank and other donors to support needed reforms. The Bank Group in general relied too much on potential benefits from the LNG-fueled extractive sector boom. The SOE sector is a major source of inefficiency in the economy; however, the World Bank has shied away from engaging in SOE reform (even though the strategies referenced the need for reform). IFC is currently involved in an electricity sector through a public-private partnership advisory that aims to introduce private concessions. The SOE reform is conducted by other donors, such as the Asian Development Bank.

Figure 2.4. Mapping of the FY08–11 Country Assistance Strategy, FY13–16 Country Partnership Strategy, Priorities in the FY18 Risk and Resilience Assessment and Systematic Country Diagnostic, and FY19–23 Country Partnership Framework

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Black arrow = strategy themes carried over; green arrow = increased strategy focus; red arrow = decreased strategy focus. CAS = Country Assistance Strategy; CC = climate change; CPF = Country Partnership Framework; CPS = Country Partnership Strategy; FY = fiscal year; GBV = gender-based violence; IFC = International Finance Corporation; PEA = political economy analysis; PFM = public financial management; RRA = Risk and Resilience Assessment; SCD = Systematic Country Diagnostic; SWF = sovereign wealth fund.

- Papua New Guinea was the fifth largest oil palm exporting country in the world in 2022, according to data from the United States Department of Agriculture International Production Assessment Division.