The World Bank Group in the Kyrgyz Republic

Chapter 1 | Background and Country Context

This Country Program Evaluation assesses the relevance and development effectiveness of the World Bank Group’s engagement in the Kyrgyz Republic. The report covers the period of the Bank Group’s fiscal years (FY)14–17 Country Partnership Strategy (CPS) and its FY16 Performance and Learning Review (PLR), and the FY19–22 Country Partnership Framework (CPF). The evaluation distills lessons from Bank Group experience to inform future Bank Group engagement in the Kyrgyz Republic.

The evaluation drills down on three themes of particular relevance to the Kyrgyz Republic’s development: governance, private sector development, and provision of essential local public services. The Country Program Evaluation responds to the following evaluation questions:

- How relevant to the development needs of the Kyrgyz Republic was the Bank Group–supported strategy, and did it evolve appropriately over time, given changes in the country context and lessons from experience? (See chapters 2 and 3.)

- To what extent did Bank Group assistance help improve governance and the institutional capacity of the central government? (See chapter 4.)

- To what extent did Bank Group assistance help the Kyrgyz Republic increase private sector–led growth to reduce the country’s economic vulnerability? (See chapter 5.)

- To what extent did Bank Group assistance enhance the provision of basic local public services? (See chapter 6.)

To conclude and inform the preparation of the next CPF, chapter 7 presents main findings and lessons.

Country Context

The Kyrgyz Republic is highly dependent on remittances and natural resources, is landlocked, and is one of the poorest countries in the Europe and Central Asia Region. In 2013, its gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was $1,282 (in current dollars), and over the following six years, it grew slowly. Remittances represented approximately 30 percent of GDP during 2013–20, making the Kyrgyz Republic one of the world’s most remittance-dependent economies. The economy is heavily dependent on gold mining, with gold representing approximately 40 percent of exports and 10 percent of GDP in 2013–19 (World Bank 2018a). The Kumtor mine (nationalized in 2021) is scheduled to close in 2031. One of the world’s highest mountain ranges separates the northern and southern regions of the country, and just under two-thirds of the population lives in rural areas. The country needs to find additional sources of private sector–led economic growth (Izvorski et al. 2020; World Bank 2018c).

Despite reductions in poverty between 2013 and 2019, the population remains vulnerable (table 1.1). Approximately 65 percent of the population lives just above the poverty line, making them vulnerable to falling into poverty if they experience a shock, and poverty remains high in areas outside of Bishkek (World Bank 2018c).1 Since independence, the country has seen a pattern of severe shocks, including natural disasters, volatile global and regional food prices, economic crises, government instability, ethnic conflict (USAID 2015), and the COVID-19 pandemic.

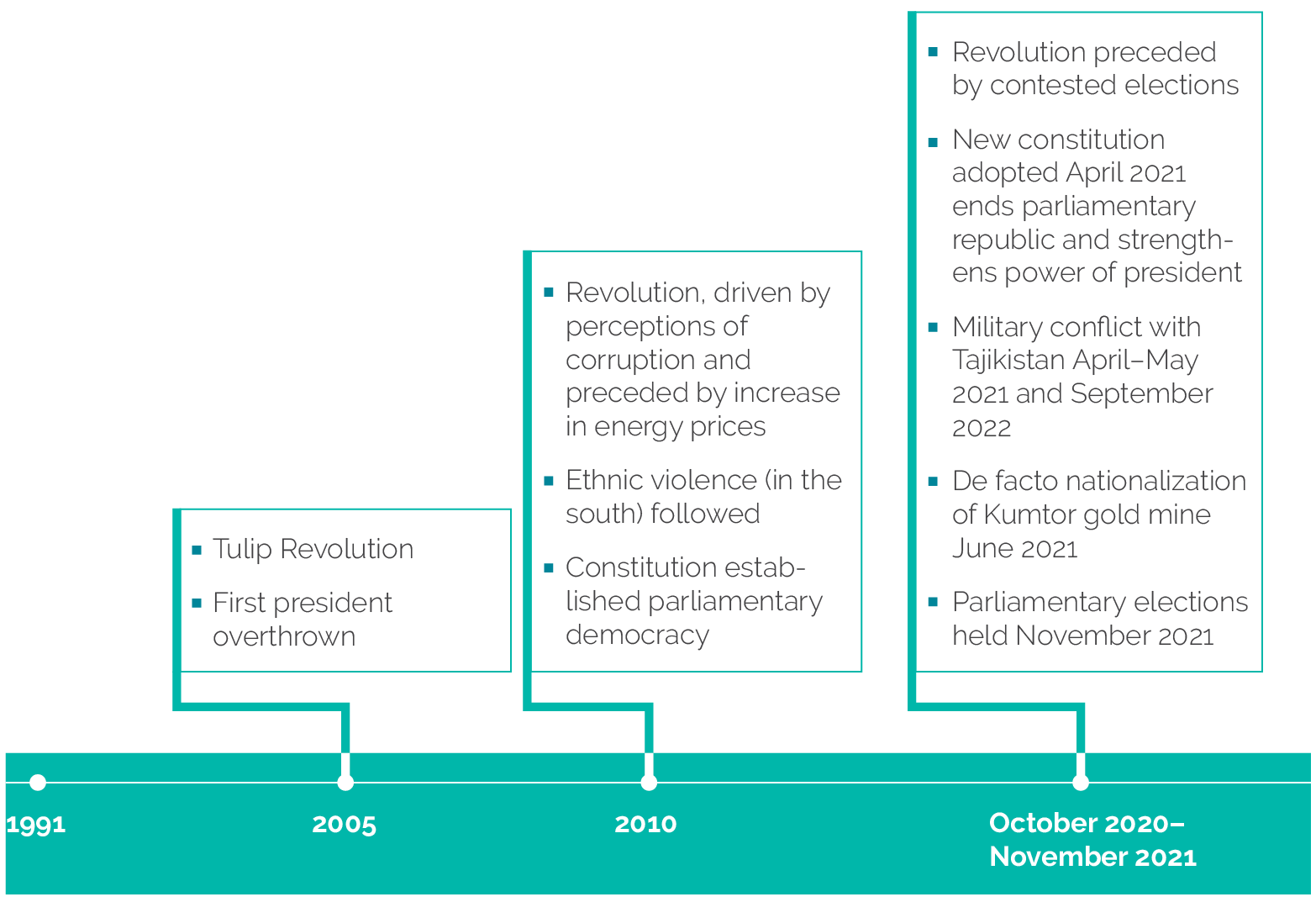

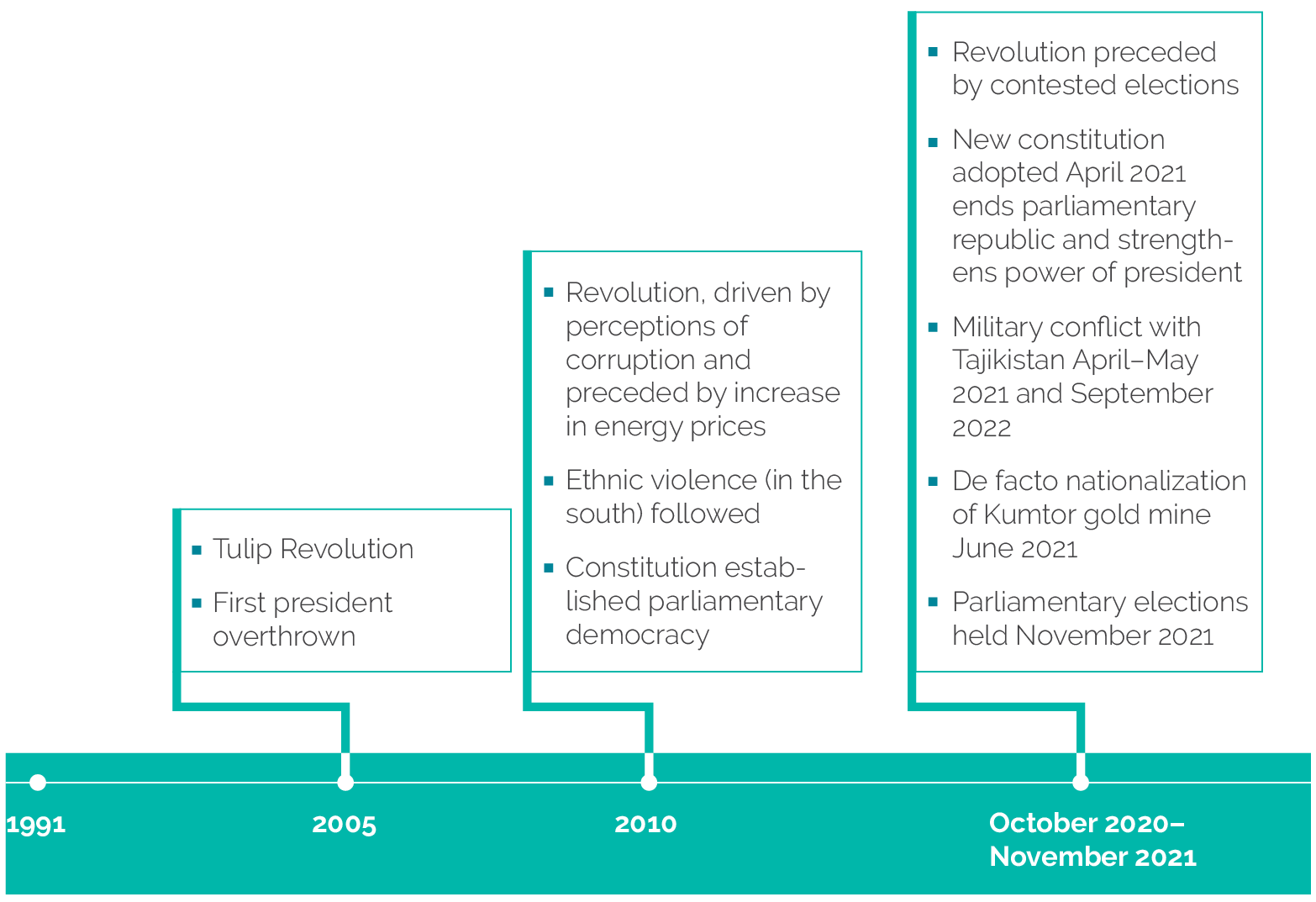

Consistency in economic policy and follow-through on reform have been major challenges because of persistent political instability. Figure 1.1 presents a brief timeline of major political and economic events. Since independence, the country has experienced three major (“revolutionary”) upheavals—in 2005, 2010, and 2020—that led to changes in leadership and were accompanied by violence and looting. The 2010 regime change was driven by perceptions of corruption and misgovernance. From 2011 through 2021, there were 10 changes of government; the average tenure of the cabinet of ministers was less than one year. Political instability was driven by competition among patronage networks for control of resources (Radnitz 2012). In 2013, 38.4 percent of firms ranked political instability as the top constraint to doing business.2 In 2019, 39.2 percent of firms ranked political instability and corruption as the top constraints to doing business, almost twice the average in the Europe and Central Asia Region and in lower-middle-income countries (Izvorski et al. 2020). As with the 2010 revolution (World Bank 2018c), the 2020 rioting and government overthrow were also driven by public dissatisfaction with the ability of the government and the legislature to create a stable political environment. The country stopped being a parliamentary republic in April 2021, when the new constitution (approved via referendum) abolished the post of prime minister and concentrated power in the presidency.

Table 1.1. Select Economic and Social Indicators

|

Indicator |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

GDP growth (annual %) |

10.9 |

4.0 |

3.9 |

4.3 |

4.7 |

3.8 |

4.6 |

(8.5) |

|

GDP per capita growth (annual %) |

8.7 |

2.0 |

1.8 |

2.2 |

2.7 |

1.7 |

2.4 |

(10.1) |

|

GDP per capita (current US$) |

1,282 |

1,280 |

1,121 |

1,121 |

1,243 |

1,308 |

1,374 |

1,183 |

|

Current account balance (% of GDP) |

(13.8) |

(17.4) |

(15.8) |

(11.6) |

(7.0) |

(11.6) |

(12.0) |

4.8 |

|

General government gross debt (% of GDP) |

47.1 |

53.6 |

67.1 |

59.1 |

58.8 |

54.8 |

54.1 |

67.5 |

|

Overall fiscal balance (net lending or borrowing; % of GDP) |

(3.7) |

(3.1) |

(2.5) |

(5.8) |

(3.7) |

(0.6) |

(0.1) |

(3.3) |

|

Remittances (% of GDP) |

31.1 |

30.0 |

25.3 |

29.3 |

32.3 |

32.5 |

27.2 |

31.1 |

|

Poverty head count ratio at national poverty lines (% of population) |

37.0 |

30.6 |

32.1 |

25.4 |

25.6 |

22.4 |

20.1 |

25.3 |

|

Gini Index (World Bank estimate) |

28.8 |

26.8 |

29.0 |

26.8 |

27.3 |

27.7 |

29.7 |

29.0 |

Sources: World Development Indicators database (World Bank) and World Economic Outlook database (International Monetary Fund).

Note: GDP = gross domestic product.

Despite the Kyrgyz Republic being an early leader among Central Asian countries in economic liberalization, broad-based economic growth remains elusive. Although the Kyrgyz Republic undertook economic liberalization soon after its independence in 1991, momentum slowed over the past two decades. Productivity has grown by only 0.5 percent per year on average since 2000, low by international standards (World Bank 2018c). The country has a large informal sector estimated at over 30 percent of GDP in 2015 (Izvorski et al. 2020). The financial sector is underdeveloped; the ratio of domestic private credit to GDP was 16 percent in 2013, having increased to 28 percent by 2020 (compared with 43 percent on average in lower-middle-income countries).

Figure 1.1. Kyrgyz Republic Economic and Political Timeline

Figure 1.1. Kyrgyz Republic Economic and Political Timeline

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

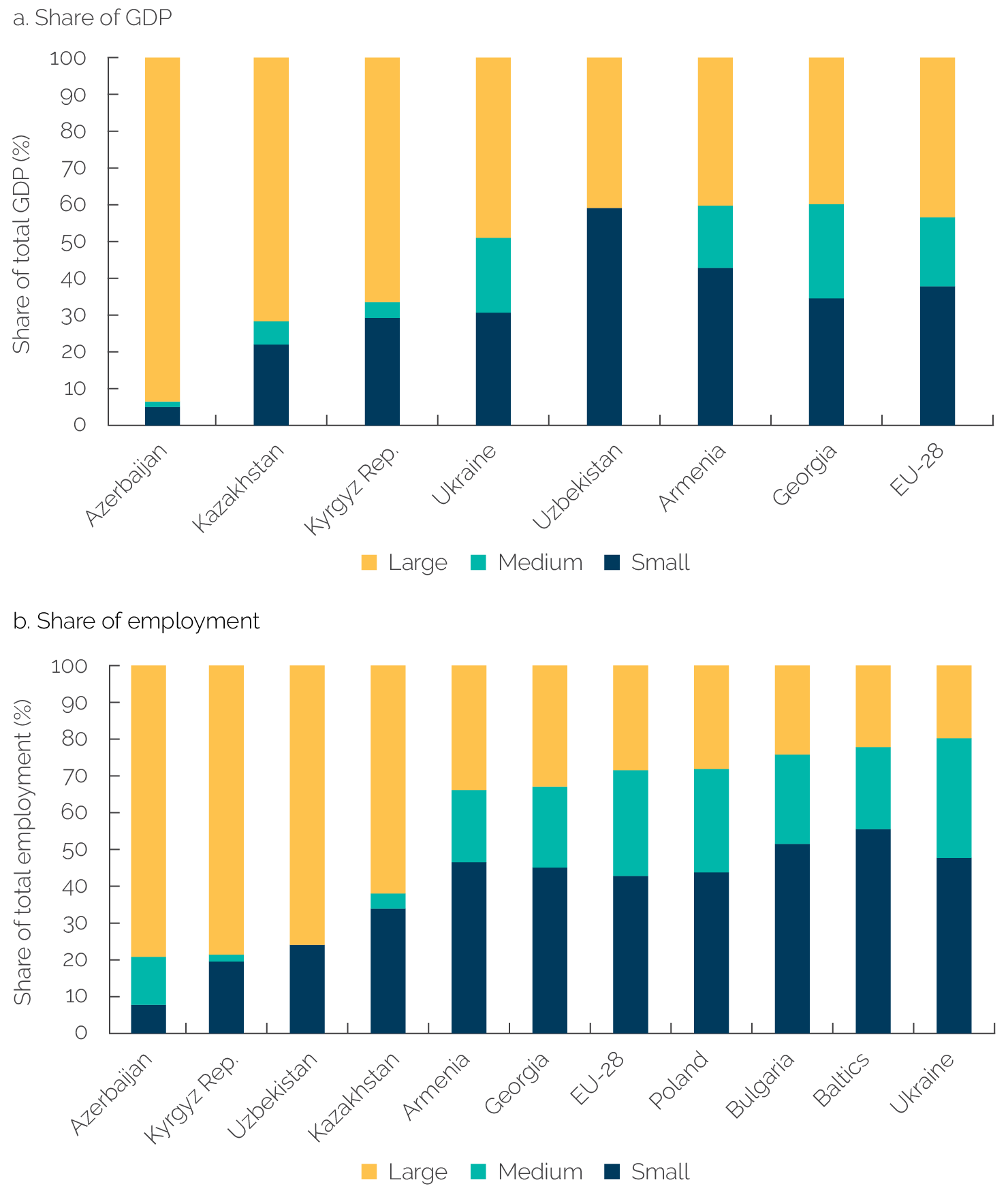

Foreign direct investment and small and medium enterprises (SMEs) play undersized roles in the economy. The Kyrgyz Republic has struggled to attract and retain foreign direct investment beyond the extractives sector, and there is little evidence of knowledge and technology spillover or backward links to the economy (IFC 2021). There is also a “missing middle” in the domestic economy; formal sector SMEs, which can be important sources of innovation and job creation, play a more limited role than in comparator countries. From 2013 through 2021, there were fewer than 800 medium-size enterprises in the country, representing only 0.1 percent of the total number of enterprises.3 Large enterprises (10 percent of which are state owned) are concentrated in mining, energy, banking, and communications. Formally registered SMEs accounted for only about 4 percent of employment and 12–13 percent of GDP between 2013 and 2021, and individual entrepreneurs accounted for 15–17 percent of employment (growing slowly over the time frame) and an average of 22 percent of GDP over the time frame, well below regional comparators with relatively open economies (figure 1.2).4

Figure 1.2. Share of GDP and Employment by Firm Size

Figure 1.2. Share of GDP and Employment by Firm Size

Source: Adapted from Izvorski et al. 2020.

Note: For the Kyrgyz Republic, the “small” category includes small enterprises and individual entrepreneurs (those licensed under the “patent” regime). EU = European Union; GDP = gross domestic product.

The Kyrgyz Republic also has deficiencies in the provision of essential public services at the local level, linked to incomplete decentralization. As a result of withdrawal of state subsidies and lack of proper maintenance after the fall of the Soviet Union, the Kyrgyz Republic experienced a collapse of the collective and state farms that delivered basic services throughout the country. Essential services delivered at the local level, such as drinking water, sanitation, solid waste collection, and maintenance of school and health buildings, became available only intermittently and, in some cases, disappeared altogether. While a series of presidential decrees established a system of local self-government, the legal framework for this system is ambiguous, and no coherent long-term strategy for decentralization has been implemented. New institutions were created; however, their powers were not clearly defined, and the legal distinction between national and local administrations is unclear (Siegel 2022).

Main Development Challenges

Governance and Institutional Weakness

Ineffective governance has been recognized as a primary development challenge for the Kyrgyz Republic throughout the evaluation period (ADB, IMF, and World Bank 2010; World Bank 2018c).5 Table 1.2 presents the evolution of key indicators over the period.

The Kyrgyz Republic performs well below average for lower-middle-income economies in terms of rule of law, control of corruption, and political instability. While the country has a vibrant civil society and relatively free press, it has continued to suffer from chronic government instability, policy inconsistency and low capacity in policy making and implementation, inability to enforce the rule of law, and inefficient allocation of public resources. The primary drivers of weak governance relate to the strength of patronage networks, fragility of political institutions, and lack of elite consensus regarding development priorities. Governance challenges and Bank Group support to address them are the subject of chapter 4 of this report.

Table 1.2. Governance-Related Indicators for the Kyrgyz Republic, 2013–21

|

Indicator |

2013 |

2017 |

2021 (or other as stated) |

|

Rule of Law score, on a scale of 0 (worst) to 100 (best; Worldwide Governance Indicators) |

13.15 |

17.31 |

14.42 |

|

Government Effectiveness score, on a scale of 0 (worst) to 100 (best; Worldwide Governance Indicators) |

31.28 |

24.04 |

25.96 |

|

Control of Corruption score, on a scale of 0 (worst) to 100 (best; Worldwide Governance Indicators) |

11.37 |

13.94 |

12.98 |

|

Firms citing political instability as the top constraint to doing business (%; Enterprise Surveys) |

38.4 |

— |

21.7 (2019) |

|

Firms citing corruption as the top constraint to doing business (%; Enterprise Surveys) |

11.5 |

— |

17.5 (2019) |

|

Corruption Perceptions Index: value (rank; Transparency International) |

24 (150th out of 175) |

29 (135th out of 180) |

27 (144th out of 180) |

|

Protection of Property Rights score, on a scale of 1 (worst) to 7 (best; rank; Global Competitiveness Index, World Economic Forum) |

2.4 (142nd out of 144) |

3.5 (120th out of 138) |

3.5 (122nd out of 144) |

Sources: Worldwide Governance Indicators; Enterprise Surveys; Transparency International; World Economic Forum.

Note: The Worldwide Governance Indicators are a research data set summarizing the views on the quality of governance provided by a large number of enterprises and citizen and expert survey respondents in industrial and developing countries. These data are gathered from a number of survey institutes, think tanks, nongovernmental organizations, international organizations, and private sector firms. The Worldwide Governance Indicators do not reflect the official views of the World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the countries they represent. The Worldwide Governance Indicators are not used by the World Bank Group to allocate resources. — = not available.

Private Sector Development Challenges

Challenges to private sector development hinder the country’s ability to develop more diversified sources of growth (table 1.3). At the beginning of the evaluation period, there were three main challenges to private sector development, and these persisted throughout the evaluation period. Table 1.3 presents the evolution of relevant indicators.

- Inconsistent application of laws and regulations. Protection of property rights was low relative to comparators. Regulatory enforcement changed frequently (limiting firms’ ability to adapt, increasing the cost of doing business, and pushing many firms into the informal sector) and acted as a disincentive to foreign direct investment.

- Firms’ difficulty accessing finance. In 2013, the Kyrgyz Republic performed substantially worse than regional and lower-middle-income country averages on domestic credit to the private sector as a percentage of GDP and percentage of firms with a bank loan or line of credit. Commercial banks concentrated mostly on short-term lending; interest rates were among the highest in Europe and Central Asia. Commercial banks justified high collateral requirements on the grounds that information on SMEs’ creditworthiness was not easily available or sufficiently transparent (IMF 2020).

- Limited capabilities within firms to conduct financial management; to develop business plans, adopt technologies, and innovate; and to comply with relevant standards, particularly food safety standards. The Kyrgyz Republic lagged behind comparators on the use of professional management and on capacity for innovation.

Table 1.3. Data on Private Sector Development Constraints for the Kyrgyz Republic and Comparators, 2013–21

|

Indicator |

Kyrgyz Republic, 2013 |

Europe and Central Asia (Excluding High-Income) Average (or Stated Alternative), 2013 |

Kyrgyz Republic, Most Recent |

Lower-Middle-Income Country Average, Most Recent |

Europe and Central Asia (Excluding High-Income) Average (or Stated Alternative), Most Recent |

|

Transparency and predictability in application of laws and regulations |

|||||

|

Protection of Property Rights score (rank; Global Competitiveness Index, World Economic Forum) |

136th out of 148 |

Comparators: Georgia 120th Moldova 131st Tajikistana 87th Kazakhstan 68th |

122nd out of 141 (2019) |

— |

Comparators (2019): Georgia 48th Moldova 108th Tajikistan 57th Kazakhstan 67th |

|

Number of international disputes in which the state is a respondent (UNCTAD Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator) |

11 (through 2013) |

Fourth-highest in ECA, after Poland with 20, Ukraine with 14, and Kazakhstan with 12 |

17 (through 2021) |

— |

Fourth-highest in ECA, after Poland with 36, Ukraine with 30, and Kazakhstan with 17 (2021) |

|

Access to finance |

|||||

|

Domestic credit to the private sector (% of GDP, World Development Indicators) |

15.7 |

51.0 |

24.6 (2019) 28.3 (2020) |

46.8 (2020) |

57.4 (2020) |

|

Firms using banks to finance investment (%; Enterprise Surveys) |

15.8 |

25.2 |

16.7 (2019) |

23.5 (2020) |

25.3 (2019) |

|

Firm investment financed by banks (%; Enterprise Surveys) |

7.5 |

14.2 |

7.2 (2019) |

— |

15.7 (2019) |

|

Firm capabilities |

|||||

|

Degree to which companies rely on professional management (rank; Global Competitiveness Index, World Economic Forum) |

133rd out of 148 |

Comparators: Georgia 82nd Moldova 111th Tajikistana 130th Kazakhstan 70th |

128th out of 141 (2019) |

— |

Comparators (2019): Georgia 80th Moldova 113th Tajikistan 115th Kazakhstan 105th |

|

Capacity for innovation (2013) Growth of innovative companies (2019; rank; Global Competitiveness Index, World Economic Forum) |

138th out of 148 |

Comparators: Georgia 118th Moldova 134th Tajikistana 51st Kazakhstan 74th |

132nd out of 148 (2019) |

— |

Comparators (2019): Georgia 108th Moldova 129th Tajikistan 61st Kazakhstan 107th |

Sources: UNCTAD Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator, World Development Indicators, Enterprise Surveys, World Economic Forum.

Note: ECA = Europe and Central Asia; GDP = gross domestic product; UNCTAD = United Nations Conference on Trade and Development; — = not available.a. Tajikistan was not included in the Global Competitiveness Report for 2013–14. The data presented are from the 2012–13 report.

Inadequate Provision of Local Public Services

The quality of essential local public services has deteriorated since independence. In the years leading up to the evaluation period, the pace of construction and restoration of social and municipal infrastructure did not keep up with population growth, distribution, and demographic changes. Where such infrastructure exists, fixed assets are worn out and the parameters of livability, quality, service level, and accessibility vary greatly. Municipalities are faced with increased pressure for the growing demand for services because of increasing urban populations.

Local governments are mandated by law to be key providers of services, but they have severely constrained capacity to sustainably deliver on this mandate. The ability of local governments to provide services was constrained by an incomplete and inadequately implemented decentralization reform, including the following:

- Lack of adequate resources. Local governments (ayil okmotu) are hamstrung by budgeting and policy frameworks that disincentivize initiative. The weak tax base of many local governments limits their ability to raise funds.

- Unclear delineation of responsibilities among tiers of government. There is no clear division of responsibilities for public services among various tiers of government.

- Weak human resource capacity. Local officials are inadequately trained, and high turnover of staff makes training an ongoing need. Most local government officials lack the professionalism and experience to govern according to the legislation (Babajanian 2015). Many members of local councils are unaware of their own roles and responsibilities.

Impact of COVID-19

The challenges facing the Kyrgyz Republic have been compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic. Real GDP declined by 8.6 percent in 2020, and 40,000 jobs were lost (World Bank 2021c). The budget deficit increased to 4.2 percent of GDP (from 0.5 percent in 2019). The poverty rate increased to 25.3 percent in 2020 (from 20.1 percent in 2019). In an April 2020 survey of businesses, 80 percent of respondents reported a decrease of more than 75 percent in revenues, and almost half of respondents had put their staff on leave without pay. The COVID-19 crisis also put a strain on health services that were already suffering from substandard conditions, staff shortages, and a weak arsenal of diagnostics (World Bank 2021c).

- See also the World Development Indicators (database), https://data.worldbank.org/country/kyrgyz-republic, and the National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic (table 5.04.00.25 “Poverty Rate”), http://stat.kg/en/bazy-dannyh.

- Data are from the Enterprise Surveys, www.enterprisesurveys.org.

- As of 2018, there were 305 large enterprises, 769 medium enterprises, 14,520 small enterprises, and 401,658 individual entrepreneurs. Data on large enterprises are from the International Finance Corporation (2021). Other data are from the National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic (table 1.1, “Number of Employees and the Amount of the Gross Added Value of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises”; accessed June 29, 2021), http://stat.kg/en/statistics/maloe-i-srednee-predprinimatelstvo. The latest data available are from 2018.

- See the National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic (table 1.1, “Number of Employees and the Amount of the Gross Added Value of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises”; accessed June 29, 2021, and November 18, 2022), http://stat.kg/en/statistics/maloe-i-srednee-predprinimatelstvo.

- Governance refers to institutional structures and processes that are designed to ensure accountability, transparency, responsiveness, rule of law, stability, equity and inclusiveness, empowerment, and broad-based participation.