World Bank Group Support to Demand-Side Energy Efficiency

Chapter 2 | Effectiveness, Scale-Up Challenges, and Factors of Success

Highlights

The World Bank Group’s demand-side energy efficiency (DSEE) approaches at the project level were mostly effective but did not lead to sufficient scale-up at the country level in terms of DSEE financing and outcomes.

World Bank DSEE interventions supported vertical scaling mostly in middle-income and industrialized countries, but support for horizontal scaling was limited in countries at all income levels. The International Finance Corporation achieved scaling, including horizontal scaling, when combining investment and advisory work. The evaluation could not assess the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency’s effectiveness because the Agency’s projects were being evaluated after this report was underway or had not yet met operational maturity to undergo evaluation at the time this report was underway.

Global programs—the World Bank Energy Sector Management Assistance Program and the International Finance Corporation Green Buildings Market Transformation Program—helped address market, institutional, and information barriers in a handful of middle-income and industrialized countries.

Challenges to scaling DSEE interventions include (i) client preferences for support of energy supply, (ii) volatile priorities for DSEE, (iii) the Bank Group’s inability to articulate tangible DSEE benefits to clients, and (iv) insufficient leverage of global programs and Bank Group convening power.

Successful scale-up was possible when (i) countries had robust policy environments, (ii) clients received strong advisory and analytical work, (iii) the Bank Group targeted large greenhouse gas–emitting entities such as state-owned enterprises, (iv) the interventions used de-risking instruments, and (v) clients benefited from cumulative engagements.

Demand-Side Energy Efficiency Portfolio

During fiscal years (FY)11–21, the Bank Group committed to 354 DSEE operations and 54 World Bank ASA projects (table 2.1). World Bank IPF and IFC investment services represented a large share of the DSEE portfolio during the evaluation period, at 83 projects and $8.7 billion commitment volume for IPFs and 137 projects and approximately $5 billion commitment volume for IFC investment services. DPF with DSEE measures corresponded to approximately $3 billion in lending (based on the share of the DSEE-related prior actions). The World Bank approved three Program-for-Results operations (in China, India, and Serbia) over 10 years. During the evaluation period, the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) issued 11 guarantees for eight projects in Bangladesh, Djibouti, and Türkiye. MIGA has increased its energy efficiency portfolio in the past few years, but the evaluation could cover only projects closed and validated between FY11 and FY21. The Energy and Extractives Global Practice (GP) led with the largest share of the World Bank DSEE investment portfolio by number of projects (51 percent), followed by the Macroeconomics, Trade, and Investment GP (9 percent). The Manufacturing, Agribusiness, and Services industry group (65 percent) and the Financial Institutions Group (27 percent) delivered most of the IFC investments by volume.

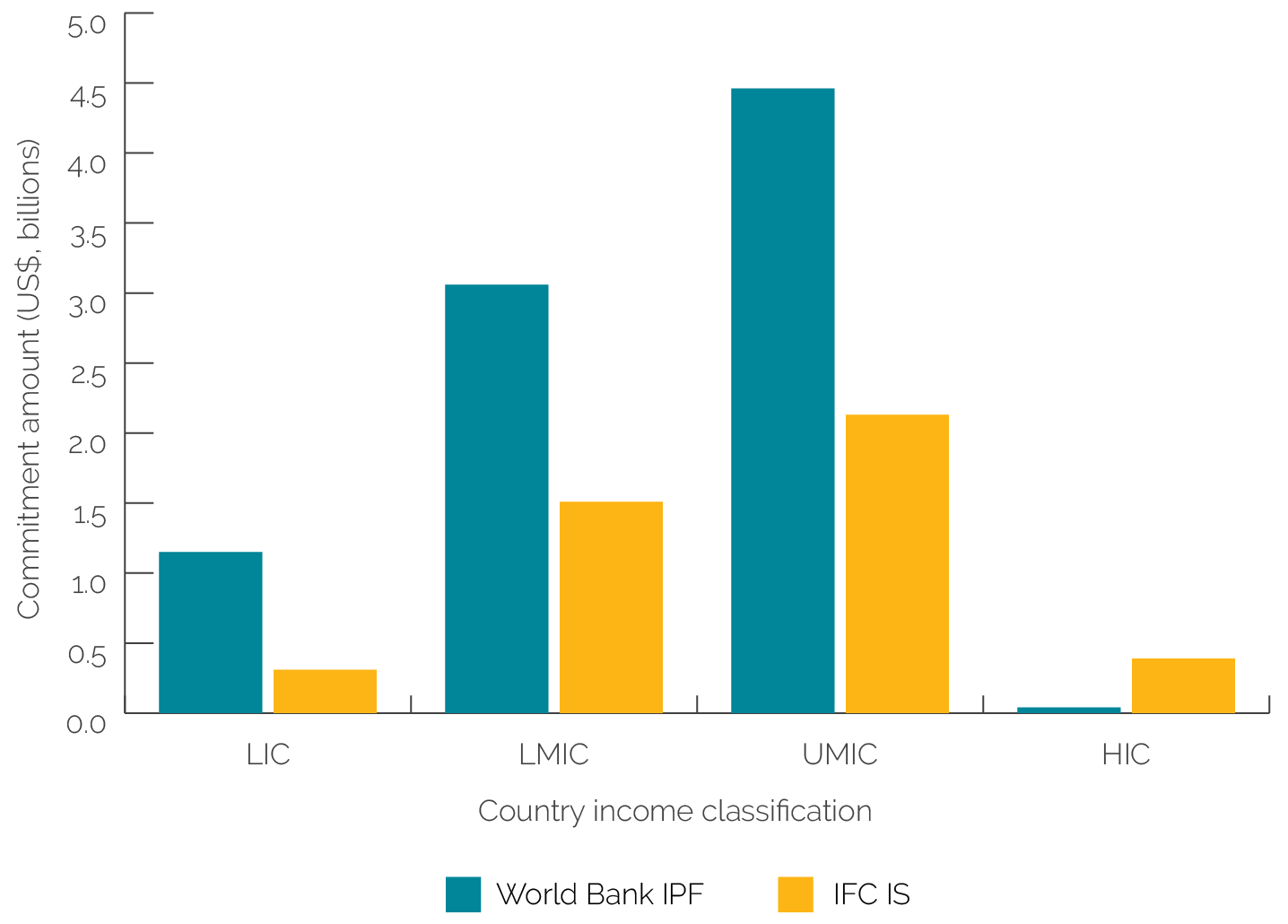

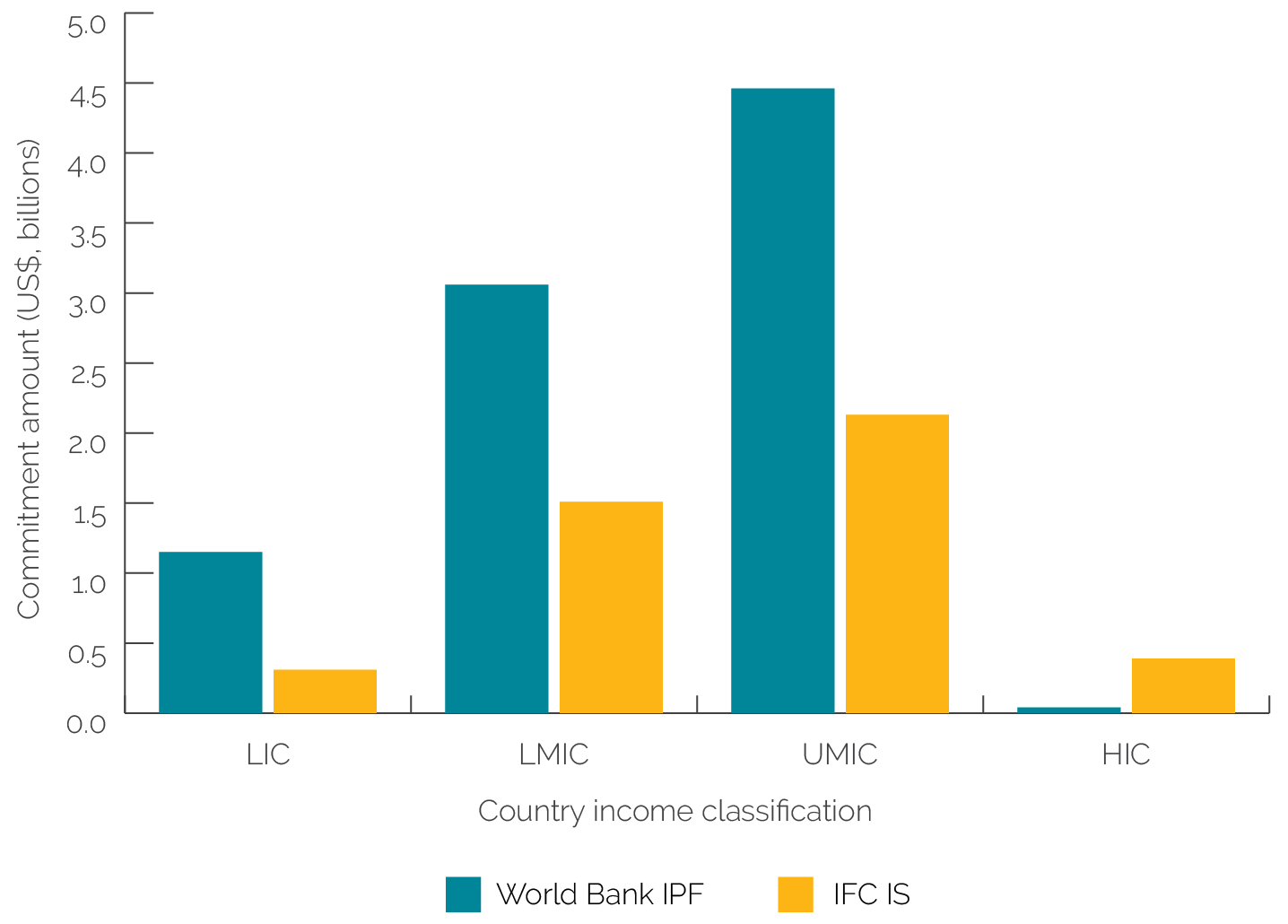

DSEE interventions reached 82 countries but gravitated toward upper-middle-income countries (UMICs) and lower-middle-income countries (LMICs). Most Bank Group lending went to LMICs and UMICs, which have higher energy intensity than high-income countries (figure 2.1). The largest share of DSEE financing for both the World Bank and IFC was in Europe and Central Asia (35 percent), followed by sizable commitments across other Regions, except for the Middle East and North Africa, which had the lowest share (9 percent). By country, the largest shares of DSEE investments were in China, India, and Türkiye, driven by client demand.

Table 2.1. World Bank Group Demand-Side Energy Efficiency Portfolio, Fiscal Years 2011–20

|

Type |

No. |

Commitments (US$, billions) |

||

|

All projects |

All projects |

Closed projects |

Active projects |

|

|

IFC IS |

137 |

4.97 |

2.57 |

2.40 |

|

IFC AS |

80 |

0.21 |

0.06 |

0.14 |

|

World Bank IPF |

83 |

8.73 |

2.12 |

6.61 |

|

World Bank DPF |

43 |

2.90a |

2.86 |

0.04 |

|

World Bank P4R |

3 |

0.84 |

n.a. |

0.84 |

|

World Bank ASA |

54 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

|

MIGA guarantee |

8b |

1.79 |

0.54 |

1.25 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: World Bank ASA is a nonlending product. Out of 408 projects, 54 World Bank ASA could not be classified into supply side or demand side, and no specific commitments value was attached to them. AS = advisory services; ASA = advisory services and analytics; DPF = development policy financing; IFC = International Finance Corporation; IPF = investment project financing; IS = investment services; MIGA = Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency; n.a. = not applicable; P4R = Program-for-Results. a. The $2.9 billion of World Bank demand-side energy efficiency (DSEE) DPF commitments shown in the table are the share of total World Bank DSEE DPF commitments ($15 billion) proportional to the share of DSEE-related prior actions in all prior actions under DSEE-related DPF (20 percent). Given the nuances between DPF and IPF accounting methods, this evaluation does not add up portfolio details across instruments.b. There were 11 MIGA guarantee contracts issued for 8 MIGA projects. Closed projects in MIGA’s context means nonactive projects (that is, terminated, canceled, or expired).

Bank Group DSEE lending mainly addressed the most energy-consuming market segments (industry and buildings), but it has not yet fully addressed the needs in the transport market segment. Globally, the industrial segment accounts for 38 percent of total global final energy use, followed by buildings and transport. The industrial sector has an extensive carbon footprint, especially in indirect emissions. The energy that buildings use across their life cycles (for example, in manufacturing construction materials, the use of fossil fuels to generate electricity and heat, and end-of-life disposal) is responsible, directly and indirectly, for approximately 37 percent of global energy-related CO2 emissions (IEA 2021d). World Bank lending (IPF, DPF, Program-for-Results) and IFC investment services targeted the needs in industrial, public, and commercial buildings and, to a lesser extent, in residential buildings as well. DSEE support in the transport market segment, however, has been minimal to date.

Figure 2.1. Distribution of World Bank Demand-Side Energy Efficiency Portfolio by Country Income Classification

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: This distribution analysis does not include development policy financing for accounting reasons explained in the final paragraph in the Evaluation Purpose, Questions, and Methods section in chapter 1 and in table 2.1. HIC = high-income country; IFC = International Finance Corporation; IPF = investment project financing; IS = investment services; LIC = low-income country; LMIC = lower-middle-income country; UMIC = upper-middle-income country.

Two global, advisory-oriented programs supported Bank Group interventions in DSEE: the World Bank Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP) and IFC’s Green Buildings Market Transformation Program (GBMTP). The World Bank ESMAP worked closely with the lending teams, IFC investment services teams, and other World Bank–administered trust funds (such as the Global Environment Facility [GEF]). ESMAP piloted new DSEE approaches through a combination of analytical work, research papers, and market diagnostics. The IFC GBMTP crowded in investment and advisory services support programmatically along with external partners to facilitate the greening of industrial and commercial market segments (box 2.1).

Box 2.1. Global Programs Supporting Energy Efficiency

The Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP) is a partnership between the World Bank and 22 development actors to help low- and middle-income countries reduce poverty and boost growth through sustainable energy solutions. ESMAP’s analytical and advisory services are fully integrated within the World Bank’s country financing and policy dialogue in the energy sector. Through the World Bank Group, ESMAP works to accelerate the energy transition required to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 7 to ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all. It also helps shape Bank Group strategies and programs to achieve the Bank Group Climate Change Action Plan targets.

ESMAP provides grants and technical support to countries through Bank Group operational units. It delivers key global knowledge products deployed for country engagements and develops external partnerships with international organizations, research and development institutions, and industry associations. It works with several Bank Group regional energy units and sectors (such as transport, urban, water, health, and gender) and mobilizes donor resources for World Bank–executed activities (for example, cofinancing International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and International Development Association operations). ESMAP raised $330 million for its business plan for fiscal years 2017–20.

ESMAP’s recent support (beginning in fiscal year 2021) to the World Bank Climate Change Action Plan implementation includes demand-side energy efficiency–related priorities. The Zero Carbon Public Sector initiative focuses on retrofitting public buildings. Industrial Decarbonization focuses on greening industrial buildings. Efficient and Clean Cooling aims to accelerate the uptake of sustainable cooling technologies and policies. The Clean Cooking Fund supports modern energy cooking services that are clean and efficient. ESMAP also supports power system planning, which helps reduce demand.

The International Finance Corporation’s Green Buildings Market Transformation Program takes a four-pronged approach to incentivize market adoption of green building practices and support greater investment in green buildings. The four prongs are (i) Excellence in Design for Greater Efficiencies (EDGE) certification, (ii) green building codes and incentives-related support to client governments and firms, (iii) investment and advisory support for the industrial and commercial segments, and (iv) investment and advisory support for commercial banks.

EDGE is the core of the Green Buildings Market Transformation Program. The International Finance Corporation created the EDGE certification system to respond to the need for a measurable and credible solution to prove the business case for building green and to unlock financial investment. EDGE is an international green building certification system implemented via a software tool. For prospective clients, EDGE sets a green building standard of 20 percent or more savings on energy, water, and embodied carbon use in materials and rewards developers for their green building projects through its certification system. EDGE certification helps create awareness and offers a verifiable performance indicator that financiers can lend against, advancing green building practices. EDGE has recently evolved to offer support to the development of zero carbon buildings, which are at least 40 percent more energy efficient than typical buildings and are fully powered by renewable energy.

Sources: Energy Sector Management Assistance Program 2022; International Finance Corporation 2019.

Effectiveness of Interventions and Scale-Up

World Bank DSEE interventions have been effective. The World Bank DSEE lending program has been successful (95 percent of closed projects were rated moderately satisfactory or above), with similar success across IPF projects and DPOs.1

The World Bank has effectively achieved energy savings and GHG emission reduction targets in its investment financing projects, where measured. IEG analyzed all closed DSEE IPFs during FY11–21 (29 projects). Of the 21 projects that specifically targeted energy savings or GHG emissions reduction, 80 percent fully achieved or exceeded their targets, and a further 18 percent partially achieved their targets. Only two did not achieve their targets. Approximately 30 percent of the projects (8 out of 29) did not measure energy savings or GHG emissions reduction. They either combined supply-side improvements with support for DSEE or focused on institutional-strengthening results, such as certifying green buildings, connecting buildings to an energy consumption monitoring platform, conducting energy audits, and creating an energy-use database.

DSEE projects often do not articulate development outcomes beyond climate and energy benefits. Of 133 sampled active and closed DSEE projects of the World Bank and IFC, only one-quarter target socioeconomic benefits such as gender inclusion, job creation, or improvement of health and well-being. For example, women are more deliberate and conscious of GHG emissions and energy use than men, according to Bank Group household surveys, but they often are not targeted in project design to increase adoption. Similarly, retrofitting buildings or greening public infrastructure, among other DSEE activities, can create net new jobs, and lowering emissions and air pollution (some arising during combustion) improves respiratory and cardiovascular health. However, jobs and health outcomes are rarely included in DSEE projects.

The World Bank used DPF to a limited extent to help develop an enabling policy and regulatory environment that promotes DSEE. Forty-three DPOs supported DSEE in 26 countries (FY11–20). Of these 43 DPOs, 28 (in 15 countries) had prior actions that supported direct regulatory, planning, or market-oriented measures to promote public and private investments in energy efficiency. These included approving energy efficiency laws and policies, setting energy efficiency standards, establishing building codes, regulating fuel quality, and mandating energy audits. Four DPOs (in Colombia, Jordan, Poland, and Ukraine) aimed to achieve market-oriented DSEE reforms, such as establishing and operationalizing an energy efficiency financing fund that could crowd in private sector capital and foster the development of energy service companies (ESCOs).2 The Poland DPO included support for white certificates, documents that certify that energy suppliers or distributors had reduced energy consumption. Only 6 DPOs in four countries out of 28 DPOs with direct DSEE policy reforms measured energy savings or GHG emissions reduction; these 6 DPOs fully or partially achieved all of the relevant targets.

The World Bank DPOs had limited impact on DSEE adoption despite progress in energy sector reforms. Nearly one-quarter of the DPOs (14) pursued tariff reforms that included increasing tariffs for end users and reducing energy or fuel subsidies, aiming to create a commercially sustainable electricity sector. The underlying rationale was that tariff charges for end users that fully reflect costs would reduce energy consumption and, thus, overall demand. Reductions in demand would, in turn, reduce GHG emissions and generate positive environmental benefits. DPOs in the Arab Republic of Egypt, Jordan, Panama, Rwanda, Serbia, Uzbekistan, and Vietnam pursued electricity tariff adjustment as part of electricity sector reforms. Contrary to expectations, the evidence collected for the evaluation does not show that the tariff reforms supported by DPOs increased end users’ DSEE adoption at scale.

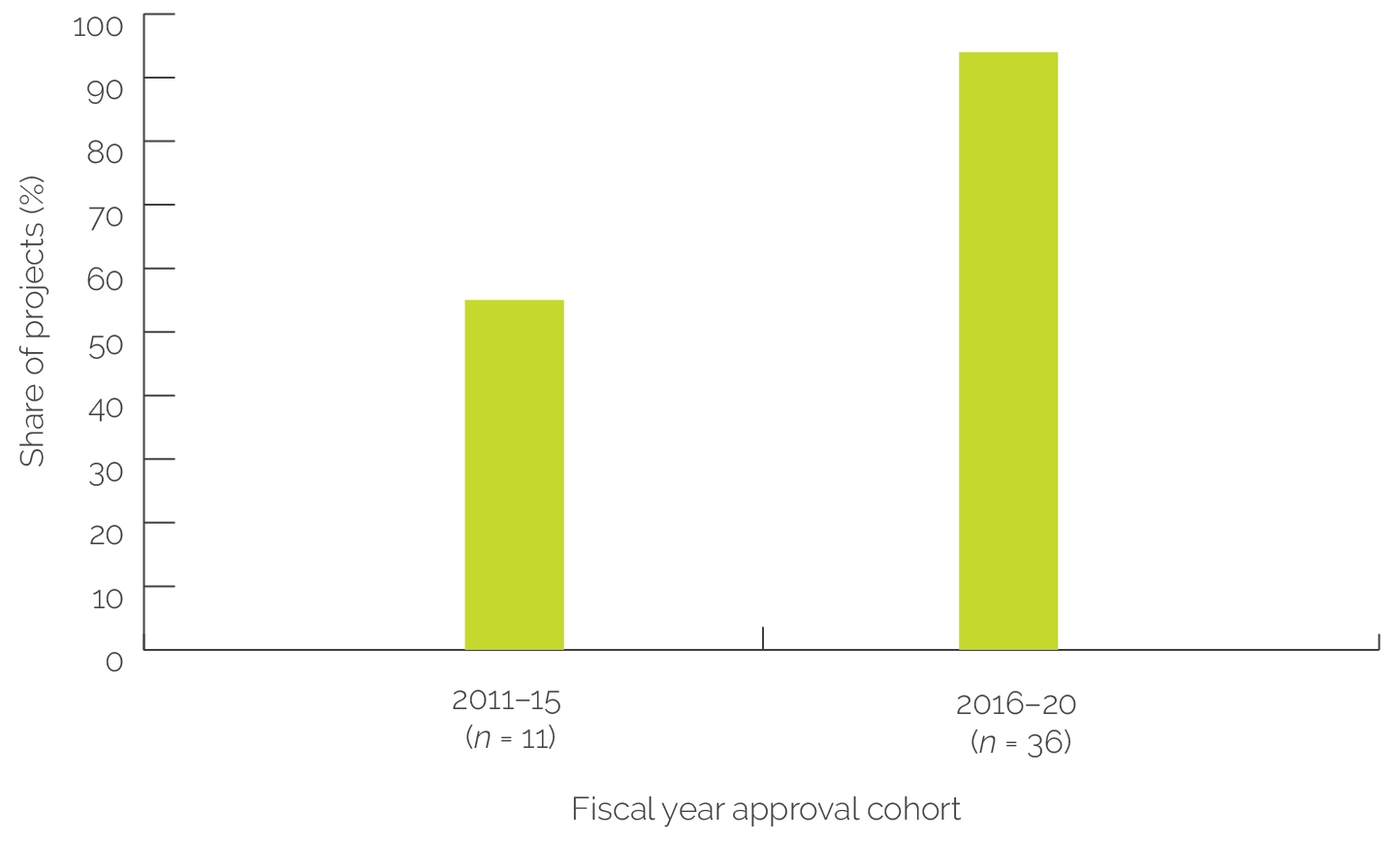

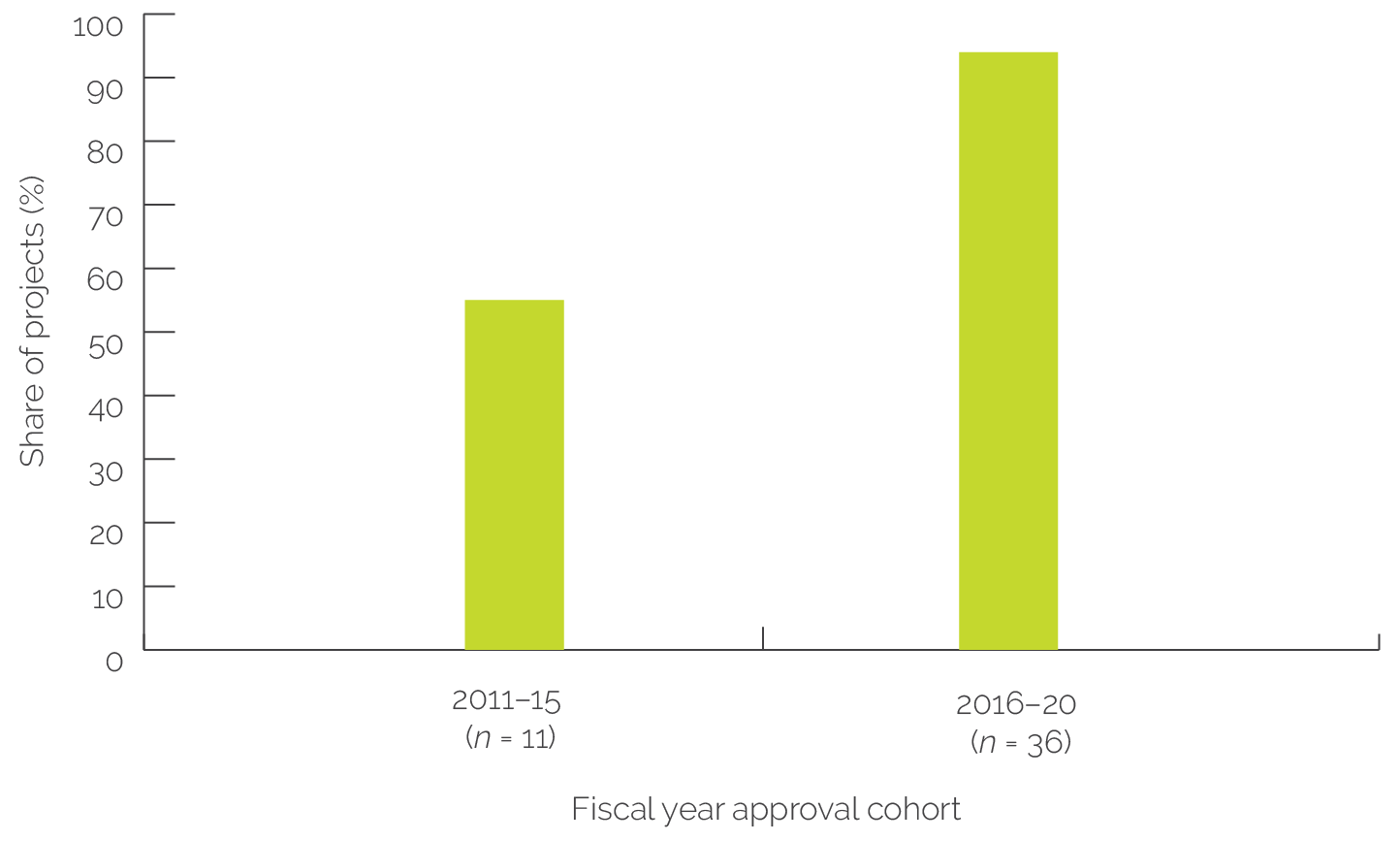

Although IFC advisory services were mostly effective, IFC investment services had limited effectiveness in achieving explicit energy savings and GHG emission reduction targets, partly because of overly ambitious development targets. IFC has increasingly targeted the primary DSEE development outcomes of energy savings or GHG emissions reduction. In FY16–21, 94 percent of IFC investment services projects targeted energy savings or GHG emissions reduction, a substantial increase from 55 percent in FY11–15 (figure 2.2), yet IFC had varied success in achieving energy savings or GHG emissions reduction. Relatively low ratings for investment services (37 percent of 13 evaluated projects) were largely due to project business underperformance driven by exogenous factors unrelated to DSEE-specific activities, such as country or financial sector conditions. The underperformance was also due to project design shortcomings such as setting overambitious objectives at entry and not meeting them. Many projects attempted to demonstrate DSEE market creation (for example, targeting new end-user segments to improve GHG emissions reduction at scale) and system-level transformation outcomes (such as reducing energy use across entire supply chains) that were not commensurate with the project design and scope of supporting a single firm or a single intermediary to promote DSEE.

The evaluation team could not assess the effectiveness of MIGA guarantees. MIGA issued 11 guarantees for eight projects with DSEE measures. MIGA is supporting a fertilizer manufacturing firm in Bangladesh to increase DSEE adoption in its activities and a business and finance center in Djibouti. In Türkiye, MIGA is supporting the Turkish Ministry of Health in renovating five public hospital buildings as part of the country’s health transformation program. Some of MIGA’s DSEE projects do not have specific targets for the DSEE outcomes (for example, energy savings, GHG emissions, water use savings), but they are making progress in greening the public infrastructure, especially in the health care end-user market segment. The evaluation could not assess their effectiveness, however, because the eight projects were being evaluated after this report was underway or had not yet met operational maturity to undergo evaluation at the time this report was underway.

Figure 2.2. Share of International Finance Corporation Investment Services Projects Targeting Primary Demand-Side Energy Efficiency Outcomes

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Most Bank Group DSEE interventions did not scale up, solving only a fraction of client countries’ needs. Many World Bank and IFC interventions with DSEE components were part of larger energy programs that did not prioritize energy efficiency gains as primary goals. Of interventions that targeted energy efficiency priorities, 66 percent (n = 96 of 146) covered single assets or groups of repeat-client small and medium enterprises without an ambition to scale. Even effective DSEE interventions with the ambition to scale often could not do so. For example, the public stock retrofits under an effective World Bank project in Armenia covered only approximately 2 percent of more than 5,800 public buildings. Another effective World Bank project in Türkiye targeting public buildings (schools and hospitals) committed $150 million to improve DSEE but could cover only 0.3 percent (500 out of 180,000 central government–owned public buildings) of the potential market segment.

Most World Bank pilot interventions, even the effective ones, were not sustained or replicated beyond project close. Although the World Bank conducted several DSEE pilots across countries and introduced innovative components in some projects during the evaluation period, most such interventions have not scaled horizontally or vertically. Many innovative pilots were completed without any further client commitments or means for scaling successful interventions. For example, a pilot DSEE project in Argentina in 2012 set up an Energy Efficiency Fund that aimed to onlend to a pipeline of subprojects to sustain and grow the market for energy efficiency services and equipment. Although the project achieved its energy use savings and GHG emissions reduction goals, the innovative approach of the government coleading the fund to stimulate a strong market-led pipeline of DSEE did not materialize. An innovative pilot DSEE project in Benin provided grants (via the International Development Association and GEF) to finance energy-efficient appliances (such as compact fluorescent light bulb upgrades and improved stoves) for the commercial and residential market segments. The project was well coordinated with multiple development partners (for example, the European Investment Bank and the Agence Française de Développement [French Development Agency]) and was a rare and successful pilot in a low-income country (LIC) client. However, it did not evolve into larger projects to develop DSEE when government commitment waned, and the lessons of experiences dissipated over time. The main reasons for lack of scale from innovative pilots across countries were volatile economic conditions, shifts in energy sector priorities toward more supply-side efforts, excess power supply, and unfavorable enabling environments.

The Bank Group was successful at scaling DSEE in a few middle-income countries (MICs), mostly through a combination of instruments and cofinancing, including from global programs. Trust funds and grants from the Clean Technology Fund (CTF), the Green Climate Fund (GCF), and the GEF, together with support from global programs (World Bank ESMAP and IFC GBMTP), helped address market, institutional, and information barriers, leading to vertical and horizontal scaling in some countries. India was able to scale DSEE both vertically and horizontally by developing a market for DSEE using support from the World Bank, IFC, ESMAP, CTF, and GEF (box 2.2). Similarly, Bank Group support allowed China and Türkiye to scale DSEE vertically. A few UMICs, including Colombia and South Africa, scaled DSEE horizontally. ESMAP also facilitated the integration of DSEE into other energy sector programs in some countries and across several sectors, creating the conditions for horizontal scaling. Examples include (i) energy efficiency and urban development, regeneration, and housing programs in Argentina, China, and Côte d’Ivoire and (ii) energy efficiency and urban resilience in the Kyrgyz Republic.

Box 2.2. World Bank Group Support for Demand-Side Energy Efficiency Market Creation in India

World Bank operations aimed to assist India’s super energy service company (ESCO) a in accessing private sector financing to scale energy savings in the residential and public market segments. A partial risk-sharing facility—the first for demand-side energy efficiency (DSEE) financing globally—started with initial financing of US$12 million from the Global Environment Facility and used a Clean Technology Fund guarantee of US$25 million to attract US$127 million of private financing. The partial risk-sharing facility removed market barriers to commercial financing for DSEE by providing loan-default risk guarantees to commercial banks that extended loans to firms adopting DSEE. An Energy Efficiency Scale-up Program (total financing US$1.43 billion) used the World Bank’s first-ever partial risk guarantee to crowd in private finance for an energy efficiency project (commercial US$200 million; development partners US$380 million). These programs used a bulk procurement model to create economies of scale, increasing supply and reducing retail prices for energy-efficient appliances and thereby creating a retail market for DSEE.

The International Finance Corporation provided advisory support to help design public-private partnership contracts for ESCOs and prepare documents to support ESCOs’ applications for commercial loans. The ESCOs paid for street lighting upgrades, operations, and maintenance and earned part of the energy bill savings. The International Finance Corporation’s advisory support also addressed the municipal government’s insufficient creditworthiness, lack of data on street lighting, lack of payment security mechanisms, and difficulty in linking public sector payments to the performance of private partners. The International Finance Corporation’s support triggered market transformation by creating and piloting replicable models for street lighting investment and incentivizing the private sector to scale. The advisory support is expected to mobilize US$100 million in private investment.

The Energy Sector Management Assistance Program, in parallel and via technical assistance, supported an in-depth market assessment for the design of ESCOs’ contract models, procurement models, and measurement and verification guidelines for energy savings.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: a. A super ESCO is a government entity or public-private partnership established to serve as an intermediary between the government and independent ESCOs.

Challenges to Scaling

There are several challenges to scaling DSEE interventions. These challenges—including challenges to leveraging financing—consist of the following: (i) client preferences for support of energy supply and clients’ volatile priorities for DSEE, (ii) the Bank Group’s inability to articulate tangible DSEE benefits to clients, and (iii) the Bank Group’s insufficient leverage of global programs (for example, ESMAP) and its convening power.

Client demand, which is focused on energy supply, has limited potential for DSEE scale-up. The main reason is the lack of client demand, often driven by client priorities related to improving energy access and electricity generation. Although governments are generally able and willing to develop supply-side energy access, generation, and utility reforms, they see less value in DSEE reforms. Disincentives to addressing DSEE include excess power supply (Ghana, Indonesia), country’s own energy resources, and (at the consumer level) below-cost energy prices (Ghana, Indonesia). Over the next three to five years, most client countries are likely to prioritize energy sector access and renewable energy generation rather than energy efficiency–related reforms, such as addressing use subsidies and creating DSEE laws and regulations to provide incentives for end-user energy efficiency to meet growing energy demand and to achieve gross domestic product growth (IEA 2021a).

Country demand for DSEE support is volatile. Several countries were affected by fragility, conflict, or violence during the evaluation period, drying up DSEE opportunities because governments had other priorities. Similarly, most LICs have insufficient energy supply and prefer to address supply-side issues before DSEE. Countries that have recently graduated to LMIC status but were LICs during the evaluation period demonstrated strong demand for energy sector reforms, including energy efficiency policy reforms. However, during the evaluation period, the need to address supply-side concerns (increasing generation, access, and distribution) limited demand from certain LMICs for Bank Group support on DSEE. For example, Ghana was an advanced DSEE reformer within Sub-Saharan Africa, but DSEE is no longer a government priority because of excess power supply (among other reasons). The Bank Group has been financing investments in transmission and distribution network improvements to reduce power loss, support the main distribution utility to improve financial and operational performance, and provide electricity access to rural areas. It also produced knowledge work and technical advice supporting DSEE measures, but there were no plans to follow through on the related interventions (ESMAP 2019, 2022).

The Bank Group’s inability to articulate tangible socioeconomic DSEE outcomes to clients limited DSEE scale-up. Bank Group interventions give uneven attention to multiple development benefits of DSEE beyond energy savings and GHG emissions and lack synergies between climate change and development impacts at the project level. There is increasing evidence that non-energy benefits play a crucial role in the decision to invest in energy efficiency. The Bank Group portfolio broadly recognizes that improvements in energy efficiency are among the most cost-effective responses to the increase in energy costs, the unpredictability and instability of energy supplies, and the growing demand for energy services. DSEE can enhance energy security and address supply-side crises, as reflected in the several efficient lighting deployment programs in Sub-Saharan Africa and the DSEE programs triggered by energy security concerns for Ukraine in 2014. DSEE’s potential to generate gains for society and the economy (for example, job creation with retrofit projects, health improvements with reduced emissions, enhanced profitability and product quality, and improved public budgets) and for decoupling growth from GHG emissions is underexplored in many countries. However, DSEE development outcomes are frequently not measured: only a quarter of the DSEE portfolio attempted to measure a DSEE development benefit not related to energy savings or GHG emissions. The World Bank’s recent Country Climate and Development Reports—as part of developing a road map for countries to transition to carbon neutrality—might help identify DSEE investments that could support clients with scaling up.

Insufficient leverage of the existing global programs and the convener on energy (ESMAP) has also limited scaling. The World Bank’s ESMAP offers a unique platform to execute collective actions with development finance institutions, governments financing trust funds for development, and the private sector. However, the World Bank has not sufficiently leveraged it. ESMAP operates with a narrow focus on promoting World Bank lending, and on this it has been successful, including in facilitating the integration of DSEE into the energy sector programs of several countries. Yet, an external evaluation of ESMAP concluded that its efforts on energy efficiency have been limited to supporting World Bank loans and that it has not yet developed a global reach and reputation (ICF International 2020). Despite its success, ESMAP lacks the mandate to support DSEE scaling globally because the priorities of specific donors and clients drive the program. ESMAP’s work is demand driven, but demand needs also to be shaped by ESMAP’s influence on global thinking; by knowledge products and events; and by funding for new tools for data collection, analysis, and modeling. In contrast to its role in energy access and renewable energy generation, in DSEE, ESMAP is more a joiner than a leader. For example, to counteract the slowing rate of energy efficiency improvements, the Three Percent Club was launched under the Climate Action Summit’s Energy Transition Track in September 2019. It is a coalition of 15 businesses and institutions committed to energy efficiency through ambitious policy measures. The Three Percent Club comprises the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the International Energy Agency, GEF, Sustainable Energy for All Energy Efficiency Accelerators and Hub, and Energy Efficiency Global Alliance, among others. ESMAP, on behalf of the World Bank, has only recently joined the group.

Factors of Success in Scaling

The evaluation has identified positive lessons with strategic implications for scaling up DSEE. Successful scale-up was possible when (i) countries had robust policy environments for energy efficiency; (ii) clients received strong advisory and analytical work; (iii) the Bank Group targeted relevant clients, such as state-owned enterprises (SOEs); (iv) the interventions used de-risking instruments; and (v) clients benefited from cumulative engagements with the Bank Group.

Factor 1: Robust Policy Environment for Energy Efficiency

A robust policy environment for energy efficiency in the client country was the common factor among all successful cases. Greater success in DSEE is observed in committed UMICs than in other countries. The main country-level incentives to address DSEE include fiscal pressure from energy-sector subsidization (Egypt, India, Morocco, Rwanda, Uzbekistan); cases when power demand is above supply (Egypt, Uzbekistan) or significant investments in new capacity are needed to cover projected steep demand increases (India); cases when climate mitigation is at the top of the government’s agenda (India, Morocco); countries at high fiscal risk because of reliance on imported fuels (Egypt, Morocco, Rwanda); countries with power and gas tariffs reaching cost-recovery level (Morocco); and countries with significant economic inefficiencies due to high energy intensity (India, Egypt, Uzbekistan). In these countries, the Bank Group has a clear role in providing financing and technical advice and knowledge for DSEE activities, such as support to industrial DSEE; DSEE market development through financing funds and ESCOs; wide-scale leveraging of commercial financing for DSEE; promotion of municipal-level DSEE, such as green buildings and street lighting; and funding household-level DSEE, such as clean cooking. The largest borrowers for DSEE support from the World Bank were China, India, and Türkiye. Although the magnitude and impact of the scale-up as a result of the Bank Group DSEE approaches cannot be quantified precisely because of a lack of data, the overall energy efficiency savings in China were approximately 16 exajoules during 2010–18 (20 percent more than the total production of electrical energy in the United States in 2001). Similarly, the overall energy efficiency savings in India were approximately 6 exajoules during the same period (about half of the yearly production of all nuclear power plants worldwide).

Parallel Bank Group support to improve the policy environment and financing of DSEE investments—rather than the traditional sequence of financing after policy reforms—can lead to successful scaling in LMICs. The Bank Group found opportunities to implement a nonsequential, opportunistic approach to DSEE reform that creates the policy, regulatory, and institutional environment for DSEE in parallel with the Bank Group’s financing. Fiscal and economic gains from energy savings create solid incentives for government buy-in and future reforms, as in Mexico and Uzbekistan. The Energy Efficiency Facility for Industrial Enterprises in Uzbekistan is a notable example of developing a sustainable financing mechanism for DSEE in a nonexistent DSEE market and an economy dominated by large and highly subsidized SOEs. The World Bank project financed a credit line to large commercial banks (two state-owned, one private) for onlending on concessional terms to large industrial SOEs for equipment modernization. The World Bank scaled the credit line through additional financing based on successful investments and repayments from subprojects. The government formally recognized DSEE credit lines as a critical mechanism for scaling industrial DSEE investments. Other development partners (such as the Asian Development Bank) started to invest in this area, involving additional commercial banks in Uzbekistan.

Factor 2: Advisory Services and Analytical Work

Knowledge work and country-specific technical assistance often guide successful investments in DSEE. Bank Group advisory and analytical support enhanced the policy environment to facilitate successful DSEE scale-up in industrialized countries (China, India, Türkiye, Vietnam). Data availability and developing data platforms proved beneficial for the Bank Group client governments’ decision-making and leveraging of climate finance (Ghana, Indonesia).

ESMAP, a global knowledge convener on energy, drove the World Bank’s ASA projects for DSEE measures, accelerating investments in DSEE. ESMAP succeeded in broadening the geographical reach of energy efficiency and piloting energy efficiency measures in sectors outside energy. This includes analytical work to identify energy-efficient investments in transport, water supply, and lighting that helped either lead to new lending operations (as in Uzbekistan) or inform operations (as in Argentina, Pakistan, and Zanzibar; ICF International 2020). ESMAP initiated support for policy reforms on urban development, building regeneration, and housing programs in Côte d’Ivoire in parallel to opportunistic investments from IFC and its cofinancing partners in low-income housing development, which led to the development of housing finance platforms and crowded in commercial investors to DSEE. ESMAP’s functions in funding, knowledge, tools, expertise, hands-on advisory support, and operational engagement have accelerated DSEE investments.

IFC, through GBMTP, demonstrated scale-up of client commitments and early development outcomes in green buildings across several Regions. GBMTP combined primary outcomes (energy savings and GHG emissions reduction) with outcomes measuring water resource efficiency and material use efficiency. It demonstrated benefits to firms, leading to increased firm-level capital commitments to energy efficiency across several Regions (figure 2.3). GBMTP uses a holistic approach that combines advisory support, lending, and the underlying Excellence in Design for Greater Efficiencies (EDGE) certification process. In Colombia, GBMTP crowded in private sector participation through the Colombian Chamber of Construction and promoted green building codes. Furthermore, it supported capacity building and awareness raising on green buildings for an extensive network of Colombian architects and engineers, staff working in Colombian financial institutions, and other practitioners. GBMTP enabled IFC to partner with Bancolombia and Davivienda to issue green bonds and invest in domestic green bond issuances. The green bonds also promoted EDGE because new project teams that wanted to qualify for green construction financing through the green bonds were required to obtain a green building certification such as Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) or EDGE. Similarly, in Indonesia, GBMTP provided a tool kit and training that conveyed essential guidance on the mandatory green building codes to Indonesia’s Ministry of Public Works and Housing for the ministry to develop its Green Building Toolkit for the country’s 33 provinces and 98 cities. The guidance followed successful models in Jakarta and Bandung. The tool kit and training accelerated the creation of a green building market. Financial institutions then partnered with IFC to develop green mortgages and construction loans. In South Africa, EDGE complemented Green Building Council South Africa in providing training to enhance awareness of green finance and the benefits of green buildings. IFC invested in a fund managed by International Housing Solutions and helped build technical capacity for applying for the EDGE certification.

Figure 2.3. Demand-Side Energy Efficiency Scale-up and Development Benefits through IFC’s GBMTP-EDGE Certifications by Region

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group; International Finance Corporation.

Note: CO2 = carbon dioxide; EAP = East Asia and Pacific; ECA = Europe and Central Asia; EDGE = Excellence in Design for Greater Efficiencies; GBMTP = Green Buildings Market Transformation Program; GJ = gigajoule; IFC = International Finance Corporation; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; m3 = cubic meter; MENA = Middle East and North Africa; MWh = megawatt hour; SAR = South Asia; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa; tCO2 = metric tons of carbon dioxide.

Factor 3: Targeting Relevant Clients

Economic gains from energy savings create solid incentives for government buy-in. The Bank Group can achieve the most significant gains in a short time from DSEE investments in large industries, including in SOEs, which play a vital role in DSEE scale-up. SOEs remain central actors in the energy sectors of client countries and adjacent sectors that are critical for contributions to Paris Agreement alignment and SDG 7.3 SOEs are responsible for nearly 40 percent of global power investment (IEA 2020d), and direct emissions from SOEs make up at least 16 percent of total global GHG emissions (Clark and Benoit 2022). The importance of SOEs is about not only GHG emissions reduction but also energy use savings they can potentially undertake across their portfolios. Targeting hard-to-abate sectors such as manufacturing and heavy industries using well-funded SOEs can be an opportunistic approach and promote DSEE scaling.

State-owned development banks play an essential role in DSEE scale-up. State-owned development banks or national development banks typically aim to finance state priorities, encourage structural transformation, and promote environmental sustainability, and in many client countries, they have taken on the role of advancing climate priorities. In the context of DSEE scale-up, state-owned development banks played critical roles as advocates, cofinanciers, direct clients, and sometimes project implementation units. For example, the 2010–19 Financing Energy Efficiency at MSMEs (micro, small, and medium enterprises) Project in India aimed to increase demand among MSMEs for investments in energy efficiency. Among other activities, the project supported training service providers to demonstrate DSEE benefits to MSMEs and install DSEE equipment. The project estimated that its activities reduced emissions by the equivalent of 16 million tons of CO2. In 2018, the state-owned Small Industries Development Bank of India, a local implementing partner, established a Green Climate and Sustainable Development Initiatives business line to promote energy efficiency and cleaner production by MSMEs (an indication of a robust policy environment). The GCF, a cofinancing partner, has accredited the Small Industries Development Bank of India business line as a national implementing entity to finance climate change projects in developing countries. Based on these achievements, the Small Industries Development Bank of India is creating a large new initiative to provide financing for multi-asset and multisectoral approaches across 5,000 MSMEs, an example of both vertical and horizontal scaling.

Factor 4: Financial De-Risking Mechanisms and Instruments

Delivery of concessional finance, grants, or guarantees can effectively demonstrate the commercial potential of DSEE financing to attract private sector investment in DSEE, creating a DSEE market. Demonstrating the commercial potential of DSEE financing adopts the model of “moving from a lending bank to a leveraging bank.” Accompanying interventions with a range of technical assistance products to leverage technical solutions, business models (including ESCO contract models and public-private partnership models for street lighting), utility performance models, and various capacity-building activities was a vital factor for success.

De-risking mechanisms and guarantee instruments were success factors in DSEE scale-ups. The lack of empirically sound, statistical data on payment default rates and the actual energy and cost savings achieved by DSEE investment projects causes financial institutions to assign high-risk premiums to DSEE investments. In this context, de-risking mechanisms (such as risk-sharing facilities and partial risk guarantee instruments) can encourage onlending through local financial institutions, helping scale DSEE. For example, the Vietnam Scaling Up Energy Efficiency Project provided $75 million to fund a risk-sharing facility. The facility aimed to issue partial credit risk guarantees for energy efficiency loans financed by participating financial institutions to end beneficiaries (industries and ESCOs). By reducing investment risk, the facility mobilized commercial financing for energy efficiency investments, a major contribution to the sustainability of energy efficiency programs in Vietnam.

Factor 5: Cumulative Demand-Side Energy Efficiency Engagements

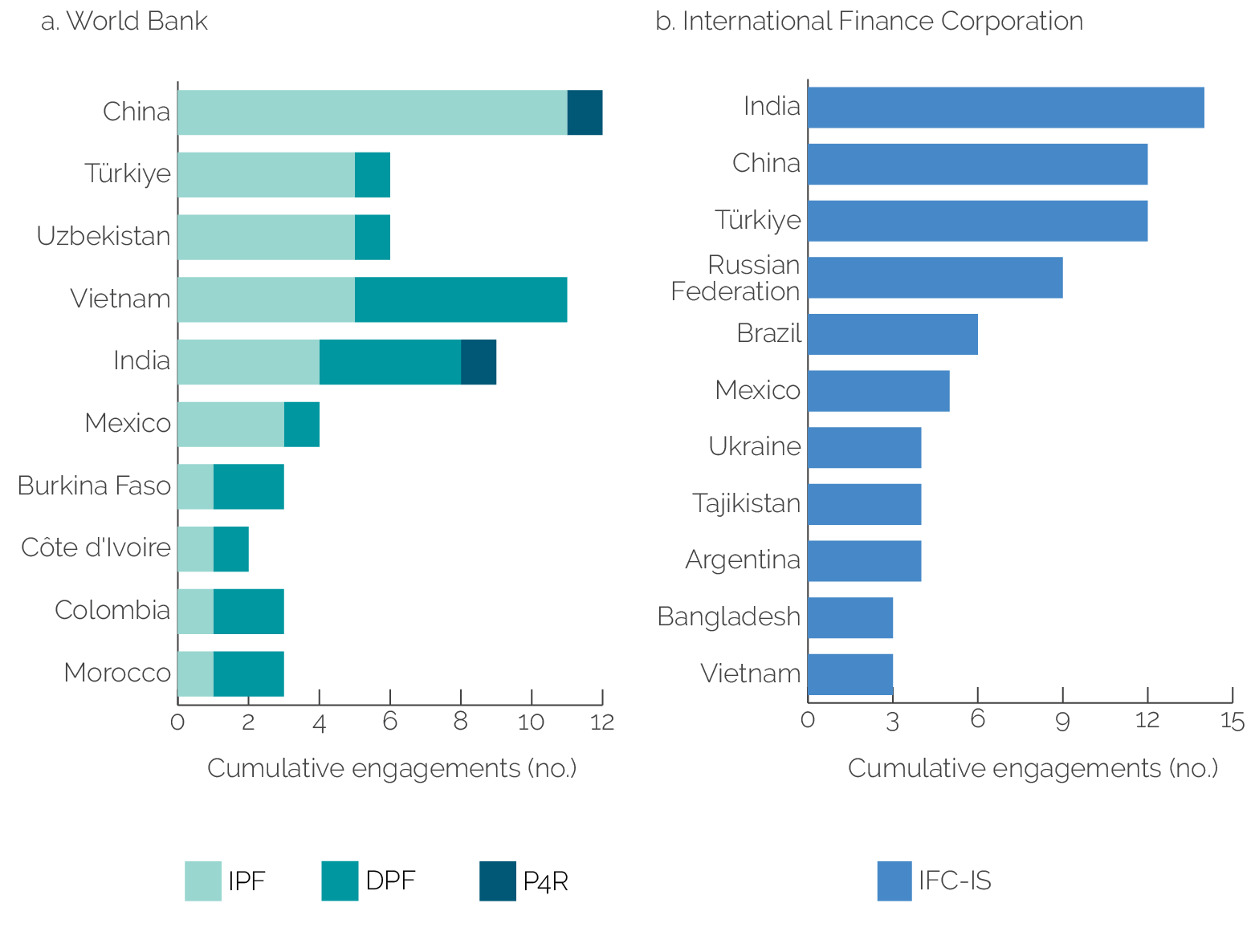

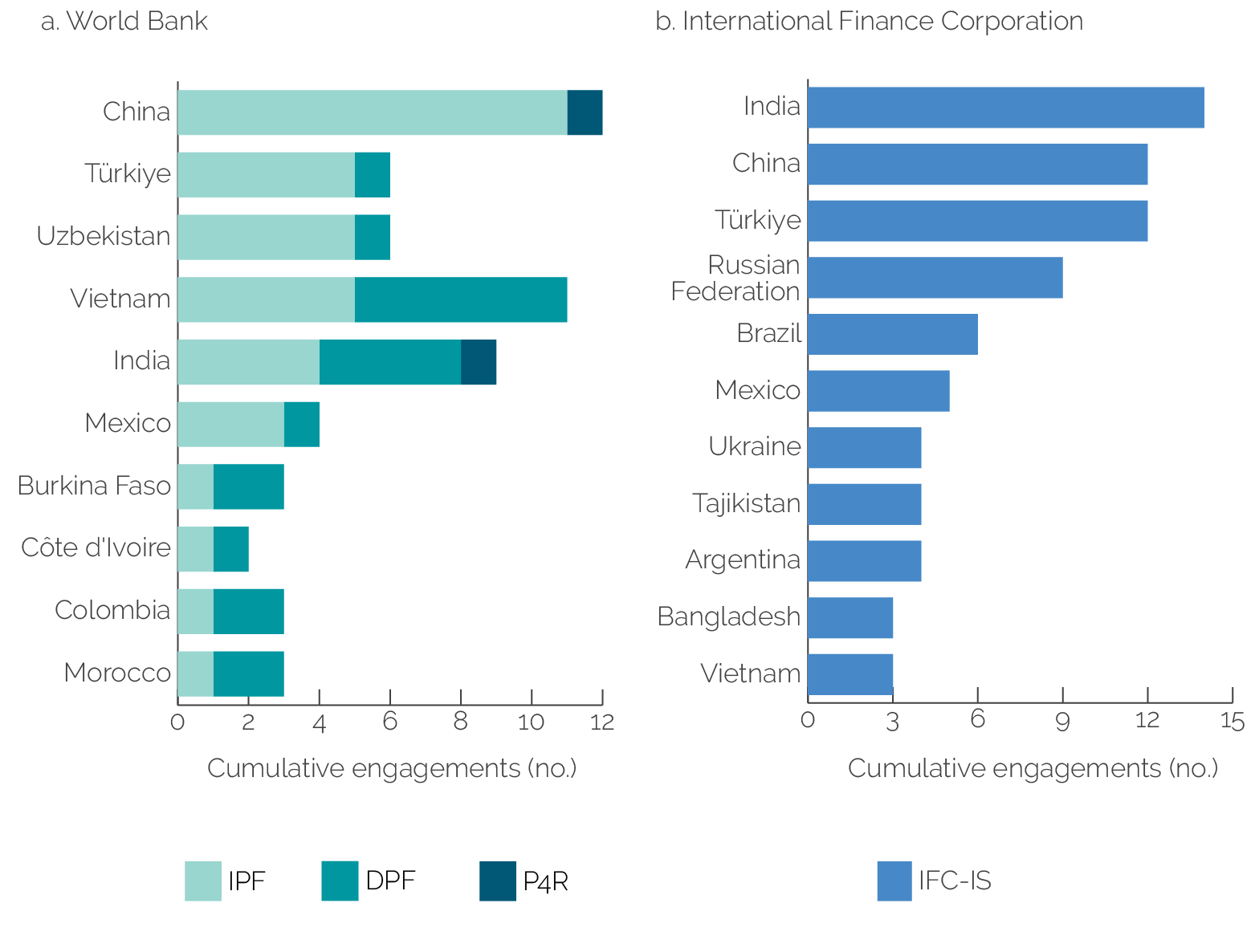

Cumulative DSEE engagements in a country are a necessary condition for scaling. Cumulative engagements are multiple interventions over time that build on one another, whether planned as a sequence or not. Cumulative engagements were limited mostly to UMICs during the evaluation period, both for the World Bank (figure 2.4, panel a) and for IFC (figure 2.4, panel b). Fewer than 20 countries have cumulative engagements on DSEE even when the original project outcome is successful, and horizontal scaling in LICs was very limited. Together, these two facts suggest that the Bank Group has the potential to scale DSEE interventions in UMICs and industrialized countries but has difficulty scaling them in LICs because of clients’ energy sector priorities and limited appetite.

Figure 2.4. Countries with Cumulative Demand-Side Energy Efficiency Engagements

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: DPF = development policy financing; IPF = investment project financing; IS = investment services; P4R = Program-for-Results.