The World Bank’s Early Support to Addressing COVID-19

Chapter 2 | Quality of Response: Relevance

World Bank financing quickly expanded emergency support to critical health services and social protection to respond to countries’ needs in a context of uncertainty.

Support to essential health services, child welfare, community engagement, and particularly protection of women and girls from the shock of COVID-19 were less prominent in early response actions.

The response was quicker and more comprehensive where the World Bank built on existing policy dialogue, analytic work, and support to human capital development, yielding a strong return on earlier investments in human capital.

World Bank support aligned with COVID-19 strategies of health ministries. In the few cases where countries planned support involving multiple sectors, integrated emergency health planning helped ensure relevant support for human capital needs.

Repurposing existing World Bank operations in country portfolios and adding new support helped mobilize surge capacities across sectors to quickly address needs during the crisis response.

Countries with existing health preparedness and health system capacities were well placed to use World Bank support to take rapid actions. Across countries, there were progressive efforts to prioritize actions for vulnerable groups and to protect human capital.

The integration of institutional strengthening brought a longer-term focus on rebuilding health, education, and social protection systems into the early response, but countries have yet to develop strategies to sustain efforts and prioritize preparedness actions.

This chapter assesses the quality of the World Bank’s support in terms of its relevance to addressing country needs in saving lives and protecting poor and vulnerable people during the early COVID-19 response. The assessment is based on dimensions of quality from the theory of action in figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1. Dimensions Assessed for Quality of Support to Need

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio.

Addressing Health and Social Needs

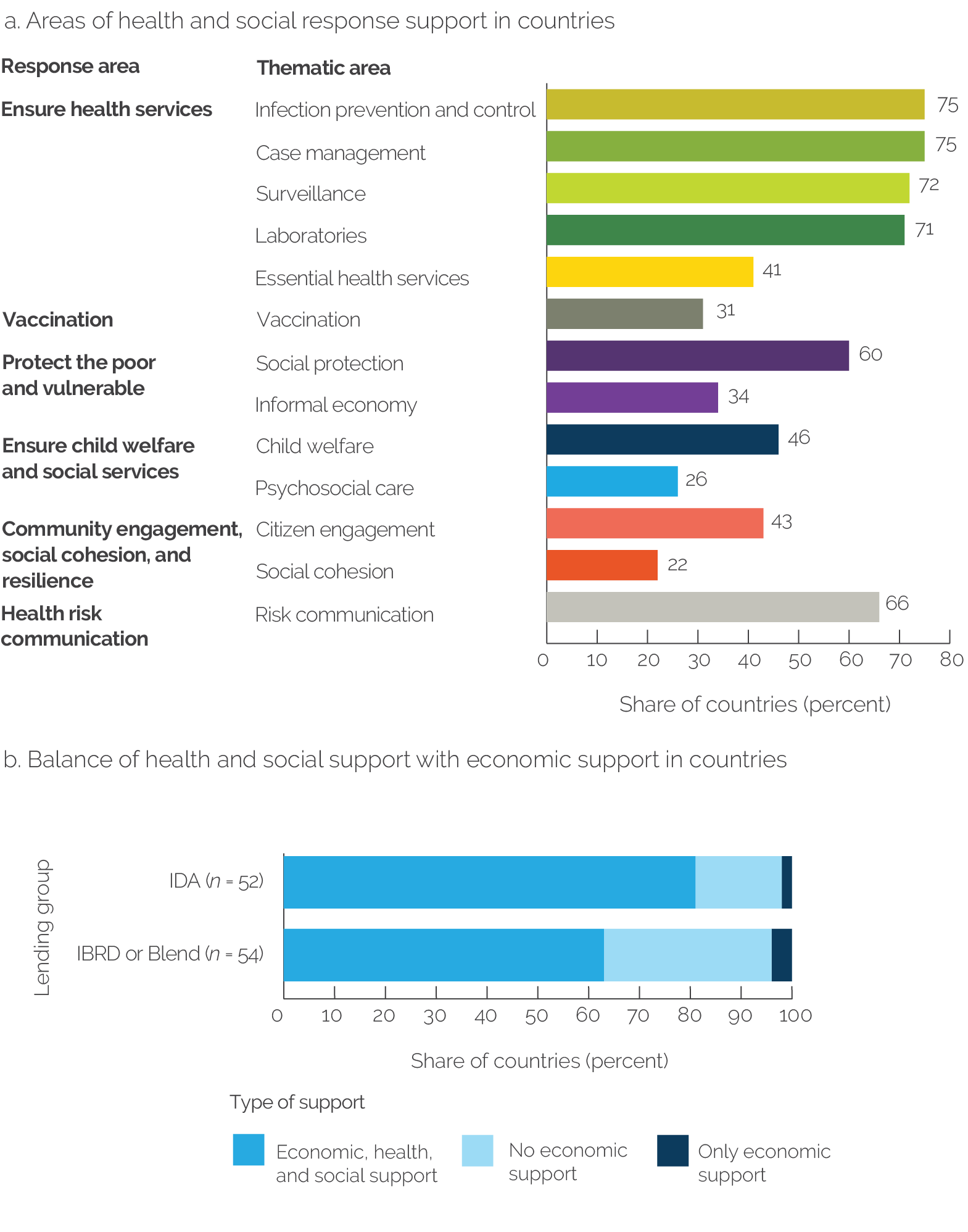

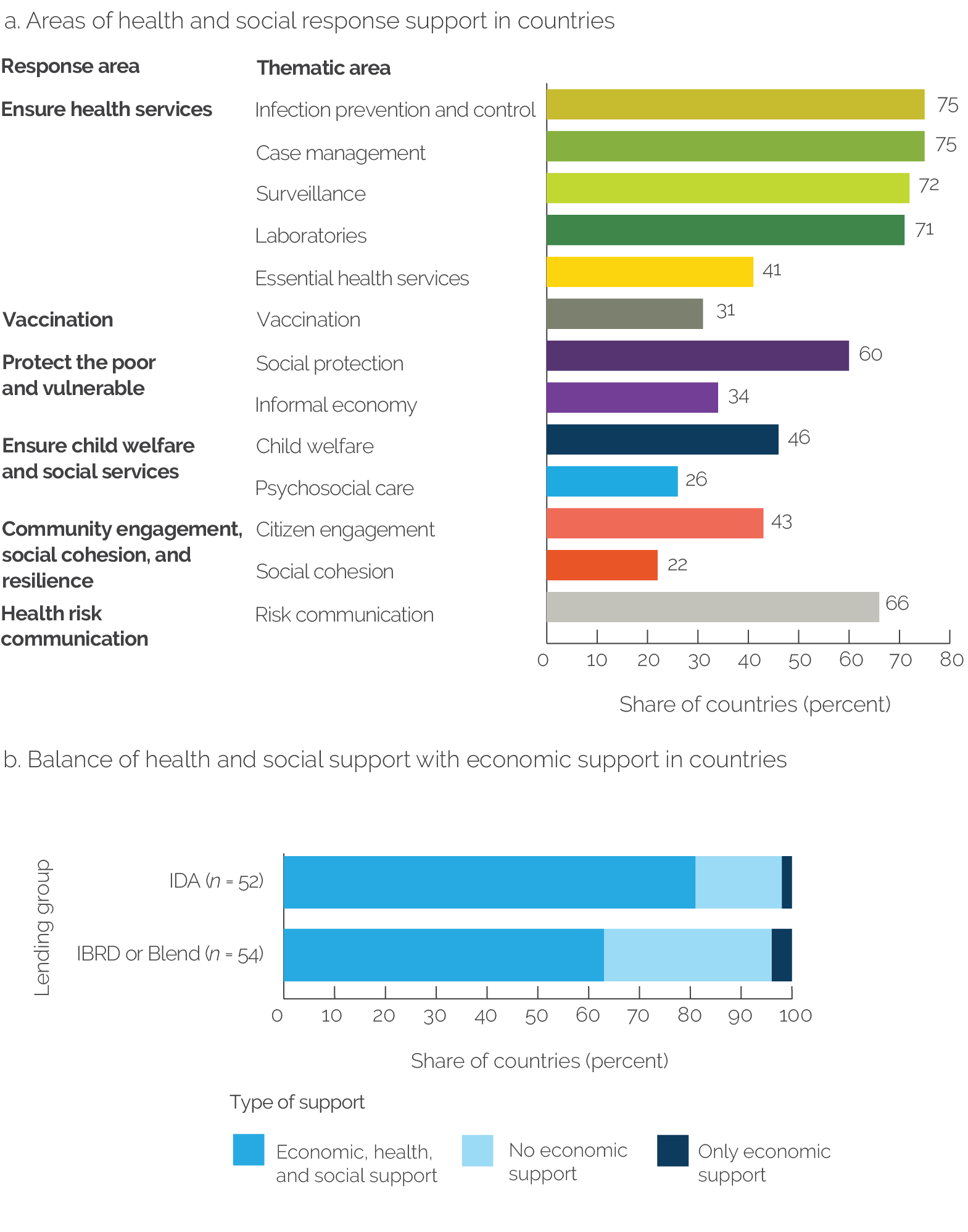

In a context of uncertainty, the World Bank’s support in the early COVID-19 response helped quickly expand critical health services and social protection across countries. More than 80 percent of countries in the evaluation portfolio received support for critical health services, and 67 percent received support to protect poor and vulnerable persons (social protection and informal economy support). Support largely focused on the delivery of critical health services, including infection prevention and control, case management, surveillance, and laboratories, and on the expansion of social protection for vulnerable groups, including income support and food support (figure 2.2, panel a). The extensive expansion of social protection during COVID-19 is an improvement from the global financial crisis where the challenges in expanding country social protection systems limited the response (World Bank 2012). Recent studies have shown that the expansion of social protection helped mitigate food insecurity and reduce increases in poverty (Gentilini 2022). The pandemic has had a highly unequal economic impact (World Bank 2022c)—the economic support complemented health and social interventions in about 72 percent of countries (figure 2.2, panel b). As noted in chapter 1, the analysis of the economic response is part of another IEG evaluation focused on COVID-19 and is outside the scope of this evaluation and is covered in a parallel IEG evaluation.

Figure 2.2. Areas of Health and Social Response Support in Countries

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio.

Note: Data in both panels are based on 106 eligible countries. Panel a covers the 253 projects in the portfolio. In panel b, support is based on 567 crisis response projects that were active at any point between February 1, 2020, and April 30, 2021. In panel b, economic support is estimated to have been provided for (i) countries where the World Bank provided support to the COVID-19 economic pillar of the World Bank’s response or (ii) countries where the World Bank provided support to the COVID-19 institutional strengthening pillar of the response led by Global Practices outside the Human Development Practice Group. IBRD = International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; IDA = International Development Association.

In the early response, the emphasis was on critical health services, disease prevention and control, and social protection and was aligned with most of the immediate needs to respond to the health and social shocks of COVID-19. The needs analysis shows that about 60 percent of countries’ needs identified at the onset of COVID-19 were addressed by the World Bank’s support (figure 2.3); in about 45 percent of countries, there was a very high alignment with country needs (appendix D).

In the early response, there was less attention to child welfare and demand-side engagement of communities. Less emphasis was given to continuing child learning and nutrition when schools and services in communities were closed. Demand-side investments in the community response, in areas of social cohesion and citizen engagement, were also limited (figure 2.2, panel a). Risk communication was planned in two-thirds (66 percent) of countries, but case studies found that the intensity of these activities was limited early in the response. Psychosocial care, essential health services, and vaccines also received less emphasis. Examples of interventions can be found in countries in each of these areas, for example, projects in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Sierra Leone both planned in-depth support to build community trust based on lessons learned from the previous Ebola outbreak. Evaluations conducted by governments and other multilateral organizations identify similar challenges of limitations in support to child welfare, community engagement, and risk communication early in the COVID-19 response (Johnson and Kennedy-Chouane 2021; OECD 2022; DPME, GTAC, and NRF 2021). Box 2.1 describes the main types of interventions in the early health and social response covered to different extents across countries.

Box 2.1. Examples of Health and Social Support for the Early COVID-19 Response

Health response:

- Case management: equip and repurpose health facilities with ventilators, oxygen cylinders, and isolation and quarantine units to care for patients with COVID-19

- Essential health services: finance supply logistics for essential medicines and telehealth to minimize disruptions to health service delivery

- Infection prevention and control: equip health workers with medical masks, N95 masks, gloves, eye protection, gowns, hand sanitizer, and other hygiene materials and help facilities develop infection prevention and control protocols

- Laboratories: train laboratory staff, update and set up laboratories, and coordinate management of testing data and specimens

- Surveillance: strengthen community and event-based surveillance for COVID-19, assess risk, and monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of activities to reduce transmission

- Health risk communication: execute communication strategies and campaigns and assess messages for population segments, such as the elderly and vulnerable groups

- Vaccination: equip countries through procurement and distribution of vaccines and essential equipment, such as syringes, cold chain, and vaccine carriers

Social response:

- Child welfare: implement safe school reopening plans with sanitation and hygiene protocols, teacher professional development programs, and continuity of child learning

- Psychosocial care: establish telepsychiatry systems, toll-free mental health hotlines, and psychosocial support for those in isolation

- Informal economy: implement public works projects, job training, and informal apprenticeships and improve information systems for informal economic activities

- Social protection: provide emergency cash transfers to vulnerable households with an emphasis on women, and pension schemes for the elderly and people with disabilities

- Citizen engagement: engage nongovernmental organizations to monitor COVID-19 response, community-based early-warning networks, and SMS communication on services

- Social cohesion: execute campaigns on gender-based violence, support girls to prevent dropouts, and support community groups and projects to promote behavior change

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio analysis.

Note: Economic response interventions that complemented the health and social response are covered by another Independent Evaluation Group evaluation. SMS = short messaging service.

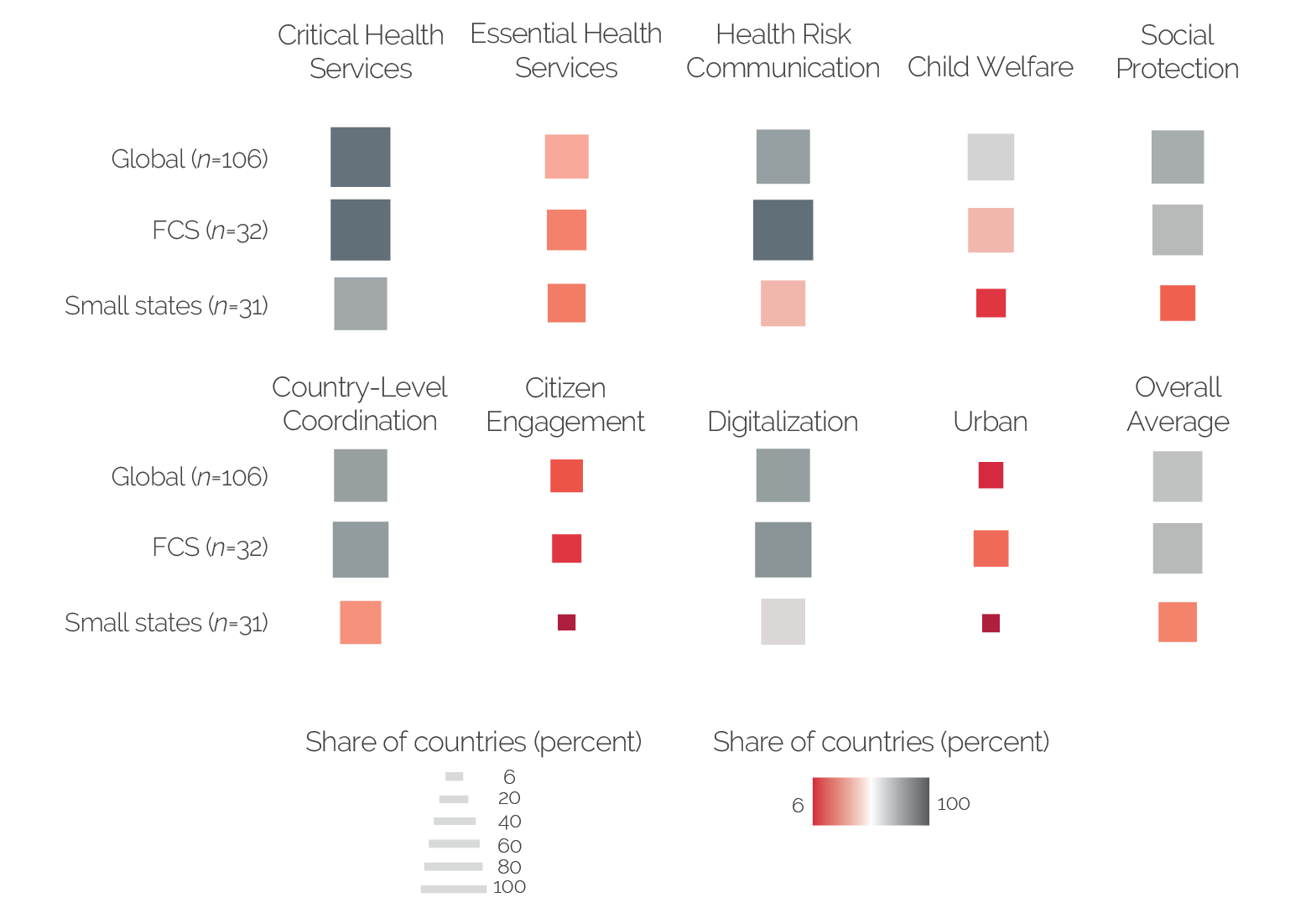

About half of countries complemented emergency support with early response actions in essential health services for maternal and child health and education to protect human capital. Other countries had limited early emphasis on essential health services and education, key for protecting human capital, especially FCS countries and small states (figure 2.3). A challenge was the lack of preparedness of countries to quickly take actions to address needs to continue essential health and education services in communities in a crisis and support urban risks, especially for vulnerable groups and in countries with weak capacities to deliver services (box 2.2). Case studies and the portfolio review highlight that MPA’s investments in critical health services likely had some spillover effects that supported essential health services. For example, in India and Haiti, the increased infection prevention and control, oxygen, laboratory, and surveillance capabilities likely helped strengthen health systems and networks to deliver services.

- In health, attention to continuing essential health services in the early response was challenging with governments requiring urgent support to expand critical health services for COVID-19 case management—needs in these areas were only met in about 48 percent of countries, which contributes to development losses in maternal and child health, especially for vulnerable groups (GFF 2021; World Bank 2022). Efforts to continue health services were later added to strengthen the COVID-19 response in some countries, building on existing health projects, where available.

- Regarding COVID-19, identified needs related to urban risks for the spread of the virus, such as in slums, were addressed in about 16 percent of countries.

- In education, where the government requested it, World Bank support helped quickly expand remote learning nationally across countries; however, needs to protect against learning losses were vast, with economic losses estimated in the trillions of dollars (Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel 2022). World Bank education interventions met needs in about 55 percent of countries.

Figure 2.3. Alignment of Project Portfolio with Identified Country Needs

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio and needs analysis.

Note: The figure shows the percentage of countries with needs in areas where the World Bank supported interventions. A need is defined as the underlying needs variable in an area falling in the bottom 50 percent of its distribution across countries. Interventions are based on the analysis of 203 projects coded for the evaluation in 89 countries that had data on needs and World Bank support. Red shading indicates that needs were addressed in less than 50 percent of countries. Gray shading indicates that needs were addressed in 50 percent or more of countries. Small states follow the World Bank definition. Data to assess the need for critical health services, risk communication, and country-level coordination use International Health Regulations data on capacities in the country before COVID-19; needs for essential health services, social protection, community engagement, digitalization, and urban support use data on access and vulnerabilities in these areas from the INFORM COVID-19 Risk Index. Appendix D describes the needs analysis. FCS = fragile and conflict-affected situation.

Box 2.2. Key Areas to Strengthen Preparedness to Address Needs in Crisis Response

Health preparedness: Comprehensive support was necessary to ensure both critical health services for preventing the spread of disease and essential health services for protecting against health-related human capital losses of women and children. World Bank support to help countries address these needs in an integrated manner was a lesson from the Ebola crisis and could have helped strengthen response efforts. The case studies and country situation analyses (appendixes C and D) show that the focus on the health emergency diverted attention from essential health services, such as maternal and child health care for vulnerable groups. Health systems were not prepared to continue essential health services during the crisis, given the need for surveillance and case management for COVID-19. Moreover, the intensity of support to frontline health workers and communities for risk communication was limited. Disruptions in the use of essential health services as a result of COVID-19 caused a secondary crisis in some countries, with drops in key maternal and child health indicators. Nutrition was also missed to protect child welfare.

Urban preparedness: Few countries with needs at the onset of COVID-19 in terms of urban risks for the spread of disease were prepared with relevant World Bank sanitation and health support for vulnerable populations, such as in slums.

Education preparedness: Case studies and the portfolio show good support to expand learning for children in countries receiving such support. The challenge was the limited coverage of this support across countries in the early response. Moreover, the education sector was underprepared for the situation and lacked a strategy to prevent learning losses among vulnerable groups and girls. Partly, this may be because the sector was often not part of previous multisector crisis response planning. The consequence is a worsening crisis with girls out of school and learning outcomes potentially reduced.

Sources: GFF 2021; Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel 2022; Independent Evaluation Group portfolio; World Bank 2021e.

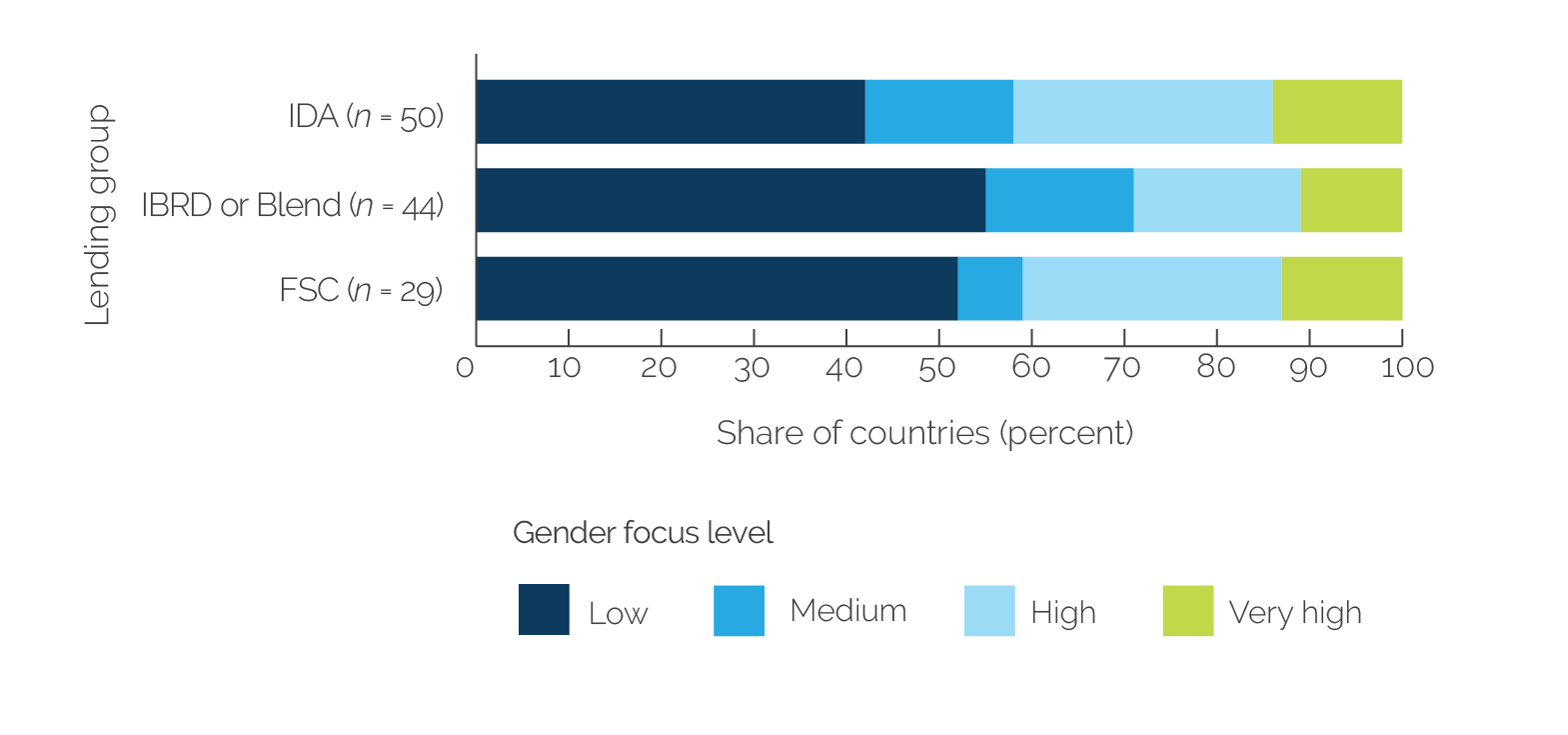

Addressing Gender

The World Bank’s preparedness to help protect women and girls from the shock of the COVID-19 crisis varied across countries. About half of countries had medium to very high World Bank support for gender equality, with more than 25 percent of projects in the portfolio addressing gender to some extent as part of their crisis response. The greater focus on gender in IDA and FCS countries was promising (figure 2.4). Support to protect women and girls was key to ameliorate impacts on health workers (often women), women caring for children, and adolescents, especially girls. For example, countries are concerned about adverse pregnancy outcomes, school dropouts, early marriage, and pregnancy, which may have adverse long-term consequences (Barış et al. 2021; Nieves, Gaddis, and Muller 2021; World Bank 2022b). However, psychosocial support, sexual and reproductive health, income and asset accumulation, reduction of gender-based violence, continued learning for girls, and community engagement were areas of limited support identified as important in past lessons (Gold and Hutton 2020; World Bank 2021e) and evidence (appendix E). The Social Protection and Jobs GP has shown the strongest address of gender issues as a core element of social protection support (about 95 percent of projects supported gender). Gender-related support of other GPs was limited; however, all GPs focused more on gender in FCS countries compared with other countries, which is promising. Evaluations from other multilateral and bilateral development organizations highlighted that addressing gender in a crisis requires building on existing approaches and systems already in place (Johnson and Kennedy-Chouane 2021; Vancutsem and Mahieu 2020). Examples of positive outliers are countries that built on their earlier experiences responding to gender equality challenges and received hands-on support:

- In Kenya, gender-based violence increased during COVID-19. Joint work between the Social Sustainability and Inclusion and Health, Nutrition, and Population GP teams sought to enhance the quality of gender-based violence services, with a focus on care and treatment by health-care providers, data collection and analysis, health sector systems for response, and the safety of female frontline health workers.

- In India, women’s organizations helped ensure the availability of personal protective equipment. Engaging these self-help groups, which have had a long history of World Bank support, ensured the provision of personal protective equipment in communities and directly benefited female-headed households.

Figure 2.4. Extent of Gender Equality Support in Country Portfolios

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio.

Note: Gender focus is defined as the share of projects in a country that were designed to address determinants of gender equality. Gender focus levels: Very low = 0 to 24.9 percent of World Bank projects in the country supporting COVID-19, medium= 25 percent to 49.9 percent of projects, high = 50 percent to 74.9 percent of projects, and very high = 75 percent to 100 percent projects. The figure excludes three countries with only regional projects (Grenada, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines). N = 94 countries. IBRD = International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; IDA = International Development Association; FCS = fragile and conflict-affected situation.

Building on Human Capital Capacities

Previous World Bank support to human capital helped ensure that countries were prepared to respond to needs for the COVID-19 response. Previously developed relationships in human development sectors, ongoing policy dialogue, and earlier investments in human development systems were a good basis on which COVID-19 project support was built. The country needs analysis for the evaluation (appendix D) found that medium to high levels of previous support to human capital development in health, social protection, and education made it almost 1.5 times more likely that the country would address health and social needs during COVID-19 at high or very high levels.1 The strong return on previous investments in human development systems helped build resilience in countries. For example, sustained investments countries made in their social protection systems in digital payments and social registries were used by the World Bank’s COVID-19 support, for example, in India, Jordan, and Morocco. Areas not addressed in the response were often those with limited attention before COVID-19, such as to address urban health risks, psychosocial care, and remote platforms to monitor community services. Case studies show that World Bank country programs with a long history of support and policy dialogue in a sector were well-situated to support the government to quickly draw on existing health and social investments for a fast response to COVID-19. For example:

- World Bank projects in Djibouti expanded on education sector networks of teachers and parents’ groups in communities to support remote learning. This reinforced a new platform to help learning in the sector.

- World Bank programs in India and Tajikistan built on earlier analytic work and projects in social protection to help the government rapidly expand national social protection systems to mitigate COVID-19 shocks.

- Senegal drew on its multisectoral One Health platform developed through earlier World Bank and partner investments to assist the COVID-19 response. The World Bank’s support to COVID-19 was able to reinforce this platform quickly and help multisectoral coordination of actions.

- World Bank teams supported the government in Uganda in fast-tracking planned reforms in the water sector to create an umbrella organization of service providers to help improve water access in local areas during COVID-19.

Alignment with Country Plans

Early World Bank support was well aligned with COVID-19 health responses in countries, with some complementary support to responses of other sectors. Country COVID-19 response plans often focused on emergency critical health and social protection support. Country responses aligned with WHO guidance (box 2.3). Other responses were fragmented across ministries, with each sector leading its own actions with limited communication across sectors. Where support was identified by the sector as important, World Bank teams often provided support. For example, in Djibouti, Senegal, and Uganda, the World Bank supported education sector strategies to expand remote learning. In Uganda, the World Bank also supported agriculture sector strategies to expand nutrition support and inputs to farmers for planting materials, and areas such as child protection policy, water services, and local government services based on government requests.

Where there was integrated cross-sector planning of health and social response actions, World Bank teams could support needs more comprehensively. Based on experiences in India and Senegal, among others, the integrated planning of health and social response support across sectors—involving health, education, social protection, government, agriculture, water, and so on—shows potential to improve crisis planning to address needs more comprehensively (appendix D). For example, in Senegal, coordinated planning across sectors (including health, social protection, agriculture, water, and others) allowed sectors to take on strategic roles in the response to cover a wide range of emergency and human capital needs.

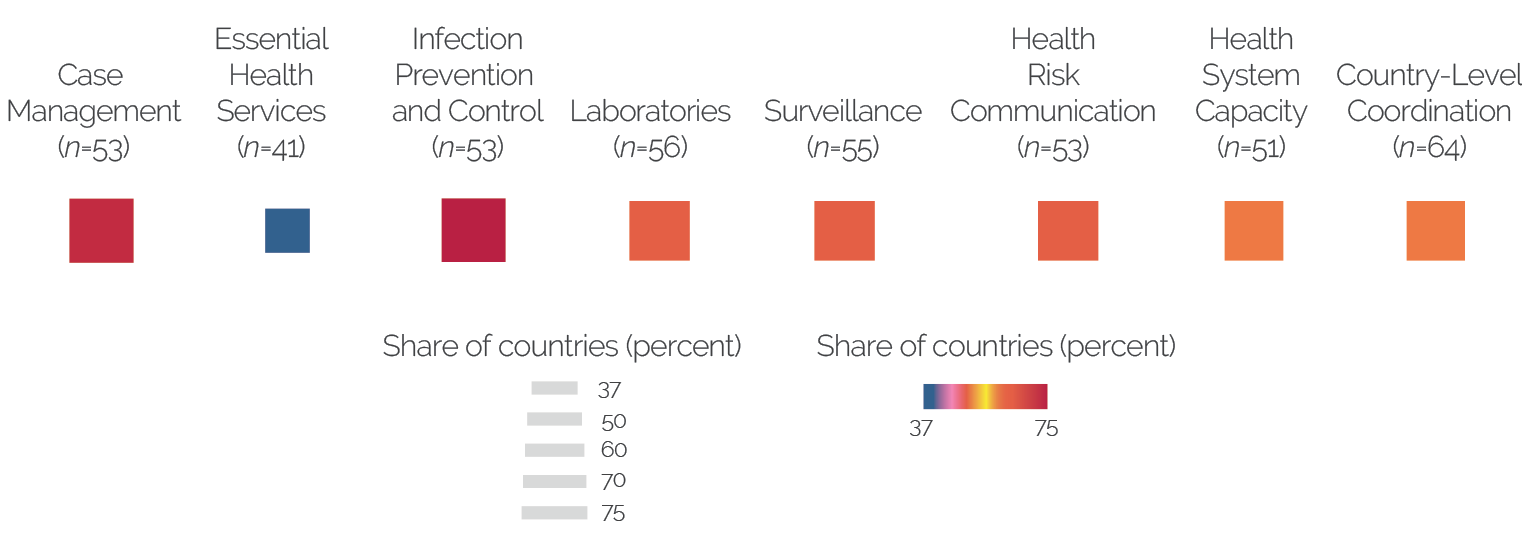

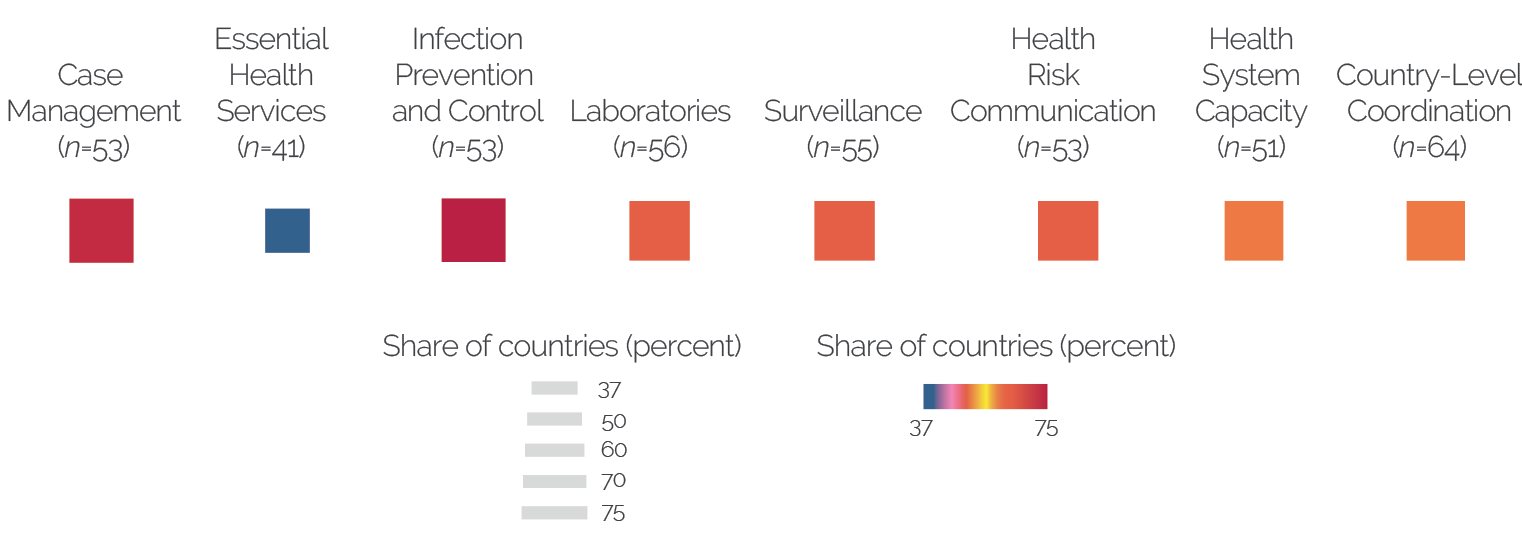

Box 2.3. Alignment of COVID-19 Support with Health Response

The World Bank’s early support aligned with national COVID-19 plans, which covered countries’ emergency health responses, typically in alignment with World Health Organization (WHO) guidance on strategic preparedness and response areas based on International Health Regulations (WHO 2021a). About 70 percent of priority areas in national COVID-19 health responses were supported by the World Bank. Figure B2.3.1 shows the alignment of World Bank support with country COVID-19 health priorities. The main area with limited support was essential health services because this was added to WHO’s global guidance later in the response, through discussions with the World Bank and other partners. Aligning with WHO guidance was critical for coordination with partners to support countries, but health responses were often not well integrated with responses of education, water, agriculture, and other sectors to help address broader needs of countries to protect human capital and vulnerable groups.

Figure B2.3.1. Alignment of World Bank Support to Health Priorities in Country COVID-19 Plans

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio; country COVID-19 plans from World Health Organization action checklists (WHO 2021d).

Note: Early World Bank health support provided limited coverage of vaccination, given the priority of prevention and control in early COVID-19 plans. Vaccination committees were set up in countries in the later months of 2020 and in early 2021. The figure shows the percent of countries that had World Health Organization plans in a response area and received at least one World Bank intervention in that area. The analysis covers 66 countries with complete data on COVID-19 plans.

Reorientation of the World Bank Portfolio to Respond to Needs

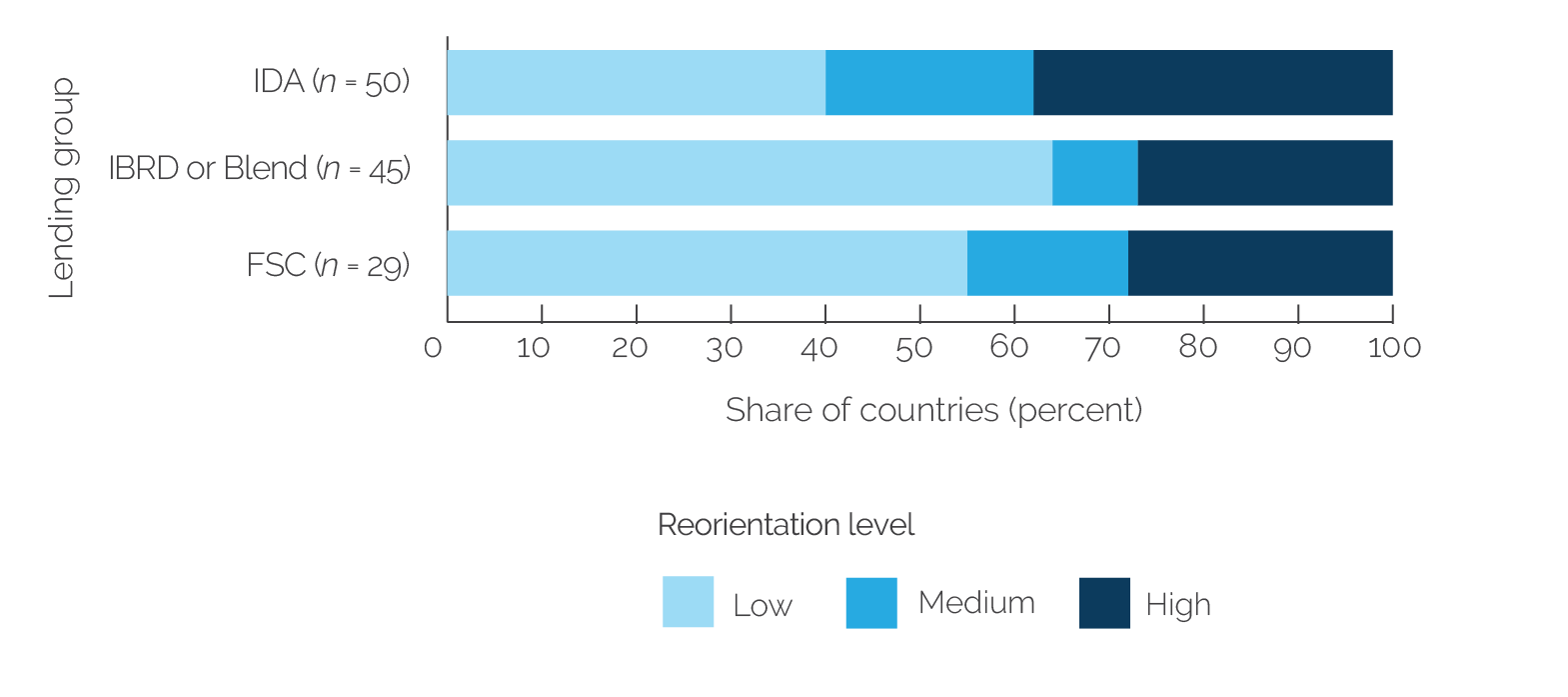

Repurposing existing World Bank support in addition to adding new interventions helped quickly address the early needs of the crisis response. About 60 percent of World Bank country programs had a medium to high extent of portfolio reorientation to address changing needs because of COVID-19, with extensive repurposing of projects and ASA in relevant sector areas and adding new support (figure 2.5). Repurposing projects already in place allowed the World Bank to rapidly address needs, often within a few days, because it built on existing structures and relationships. It also drew on surge capacities across sectors by mobilizing relevant existing support in the portfolio for the COVID-19 response. GPs were often able to repurpose relevant projects by adjusting components to strengthen the project’s relevance in the evolving context and, in some cases, fast-tracking previously planned support. For example, Djibouti adjusted urban support for slums to support health risk communication and to prevent the spread of infection. India adjusted existing state-level projects to support needs related to education, health, and urban risks, complementing new project support. Uganda adjusted its nutrition support to include health risk communication and ensure continued promotion of nutrition practices throughout COVID-19.

Reorientation of the portfolio to address needs was quick in countries with crisis preparedness. Case studies show that World Bank country programs with previous crisis experience had a high extent of portfolio reorientation—reorienting five or more projects and ASA in the portfolio—to engage the support of multiple GPs in the COVID-19 response to address needs. Sixty percent of IDA countries reoriented four or more projects and ASA in their portfolios. About half of countries had a low extent of portfolio reorientation, with limited repurposing of projects to add to new support for the early COVID-19 response. In addition, portfolio reorientation was slightly lower in FCS countries (figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5. Extent of Portfolio Reorientation in Countries

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio.

Note: Reorientation is defined as the number of projects per country identified by the evaluation as responding to COVID-19, including financing projects and advisory services and analytics (ASA) support. Reorientation levels are defined as terciles of its distribution across countries. Low: reorientation ≤ 3 projects or ASA; medium: reorientation = 4 projects or ASA; high: 5 projects or ASA ≤ reorientation ≤ 17 projects or ASA. Figure includes countries with both project and ASA support and excludes three countries with only regional projects (Grenada, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines). The total number of countries is 95. IBRD = International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; IDA = International Development Association; FCS = fragile and conflict-affected situation.

Prioritization of Support to Needs in Countries

Prioritizing World Bank support to address urgent needs was easier in countries with better health systems capacity and readiness to respond, though case studies show good efforts across most countries to focus response actions progressively on areas of need and vulnerable groups. The clustering analysis for the evaluation (appendix D) found that the portfolio included countries that fall into three main situations in terms of their prioritization of World Bank support to the COVID-19 response to align with needs (box 2.4 describes these three situations). The analysis shows that prioritization was most challenging in countries with weaker health systems, which lead to slower government responsiveness to act on emergency measures, such as gathering restrictions, masks, testing, and contract tracing, and extensive health and social needs. These countries often needed support to expand the health response and had multiple needs for protecting human capital losses of vulnerable groups as a result of COVID-19. Case studies show that in countries such as Mozambique and Uganda, where initial prioritization of the response to address the many urgent needs was challenging, there was a progressive effort to focus COVID-19 support (such as risk communication, essential health services, and nutrition support) on vulnerable groups. Focusing interventions on vulnerable groups, local health services, and hot spot geographical areas was an important complement to helping government to quickly expand national disease response capacities.

Box 2.4. Country Situations Regarding Prioritization of COVID-19 Response Actions

Countries where prioritizing World Bank support to address needs was facilitated by strong government responsiveness and preparedness:

- About 11 percent of countries in the evaluation portfolio quickly tailored World Bank support to priority needs, including a focus on vulnerable groups. For example, India had early government responsiveness and some existing epidemic response capacities (relative to other countries in the evaluation) to put health measures in place; India focused the World Bank’s support on the national expansion of social protection systems, health services in urban areas, and education for vulnerable groups. The government of Honduras quickly focused World Bank support on laboratories and developing epidemic response capacities. Djibouti had rapid government leadership to focus on needs related to urban slums, education networks in communities, and development of disease response capacities, including early support to vaccines. In Senegal, early government response and preparedness helped quickly focus the World Bank’s support to reinforce the country’s multisectoral response, which included health, nutrition, social protection, education, and other support to address multiple needs.

Countries where prioritizing World Bank support to address needs was facilitated by better capacities to deliver health services before COVID-19:

- About 53 percent of countries in the portfolio had better health systems capacities to deliver services before COVID-19, which helped them focus their response in a few areas to address needs relating to health and social shocks among vulnerable groups. These countries often faced a high number of cases of COVID-19 in the early response and also had good levels of government responsiveness to put prevention and control measures in place. For example, the World Bank’s response in Tajikistan focused on expanding social protection, laboratories, early vaccination, and citizen engagement. In the Philippines, the World Bank focused its response on community engagement, redeveloping dialogue with the government to strengthen health systems, and expanding social protection for vulnerable groups.

Countries where prioritizing World Bank support to address needs was challenging and progressive throughout the early response, given limited health systems capacities and extensive human capital needs:

- About 36 percent of countries in the portfolio had extensive health and social development needs before COVID-19 and low human capital; the key for these countries was protecting against losses of human capital. These countries also often had a lower number of reported cases early in the response and limited surveillance capacities to track cases. Among these countries, health service capacities were often limited, even when there was preparedness before COVID-19. Some countries in this groups (such as Mali and Mauritania) worked with World Bank regional projects during COVID-19, which helped engage government and supported progressive decisions to focus attention on geographical hot spots (such as border areas), laboratory interventions, and case management. Countries such as Niger and Uganda had support across sectors to address needs, but the health response was limited by existing health system capacities; prioritization to focus on the needs of girls and vulnerable youth, for example, was through the progressive strengthening of actions and often through the use of advisory services and analytics to inform actions.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group situation analysis.

Note: Appendix D includes the clustering analysis.

Use of Knowledge Work to Inform Needs

Just-in-time ASA to assess emerging needs was key to reorient and prioritize support. ASA was used in about 60 percent of countries. Key in countries was having ASA with some immediate, just-in-time outputs to inform the response. ASA was mainly for diagnostic analysis, technical assistance, studies to monitor the impact of COVID-19, and policy analysis (table 2.1). Conducting just-in-time ASA jointly with the government and partners helped support agreement on response needs and develop actionable strategies. Previous evaluations show that preparatory ASA undertaken to support crisis response helps design effective crisis lending and analytic projects (World Bank 2012, 2017). Moreover, countries need to balance longer-term ASA to inform actions for recovery and just-in-time ASA, which can provide more rapid diagnostics for immediate response needs. The production of global and country knowledge products has continued to increase after the evaluation period to inform the evolution of response actions, for example, the 2022 World Development Report (World Bank 2022c). Examples of just-in-time ASA included the following:

- In Djibouti, a gender analysis supported the response to COVID-19 in slums.

- In India, the Transport GP conducted a just-in-time diagnostic of supply chain logistics during COVID-19 that helped the government plan for the delivery of oxygen and address the challenge of short supplies.

- In Uganda, an assessment of COVID-19 communication helped the government develop a strategy to better engage vulnerable youth and women and girls.

Table 2.1. Examples of Advisory Services and Analytics Supporting the Response

|

Type of ASA |

Examples |

|

Diagnostic analysis 93 percent (17 percent multicountry) |

|

|

Policy influence 67 percent (9 percent multicountry) |

|

|

Monitoring of COVID-19 response 63 percent (13 percent multicountry) |

|

|

Technical assistance 61 percent (15 percent multicountry) |

|

|

Knowledge sharing 42 percent (12 percent multicountry) |

|

|

Knowledge generation 29 percent (11 percent multicountry) |

|

|

New evidence on effectiveness 28 percent (8 percent multicountry) |

|

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio.

Note: ASA are ordered based on the weight of their use in the COVID-19 response. Regional is used to describe multicountry ASA. Percentage in parentheses refers to ASA that addresses more than one country in a region or globally. ASA were coded by their main uses; thus, one ASA could include multiple types of analyses. Thirty percent of ASA support was regional. ASA = advisory services and analytics.

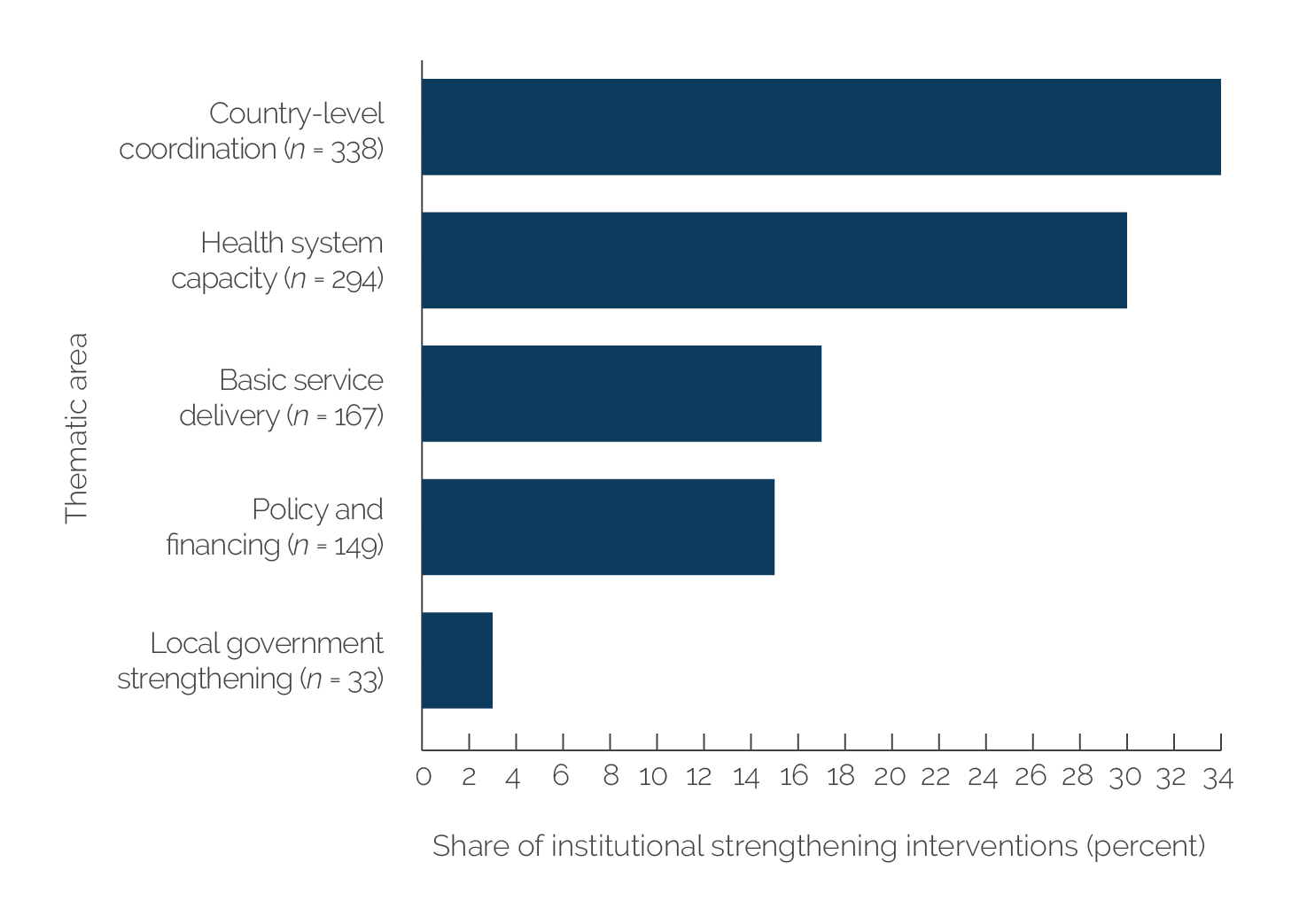

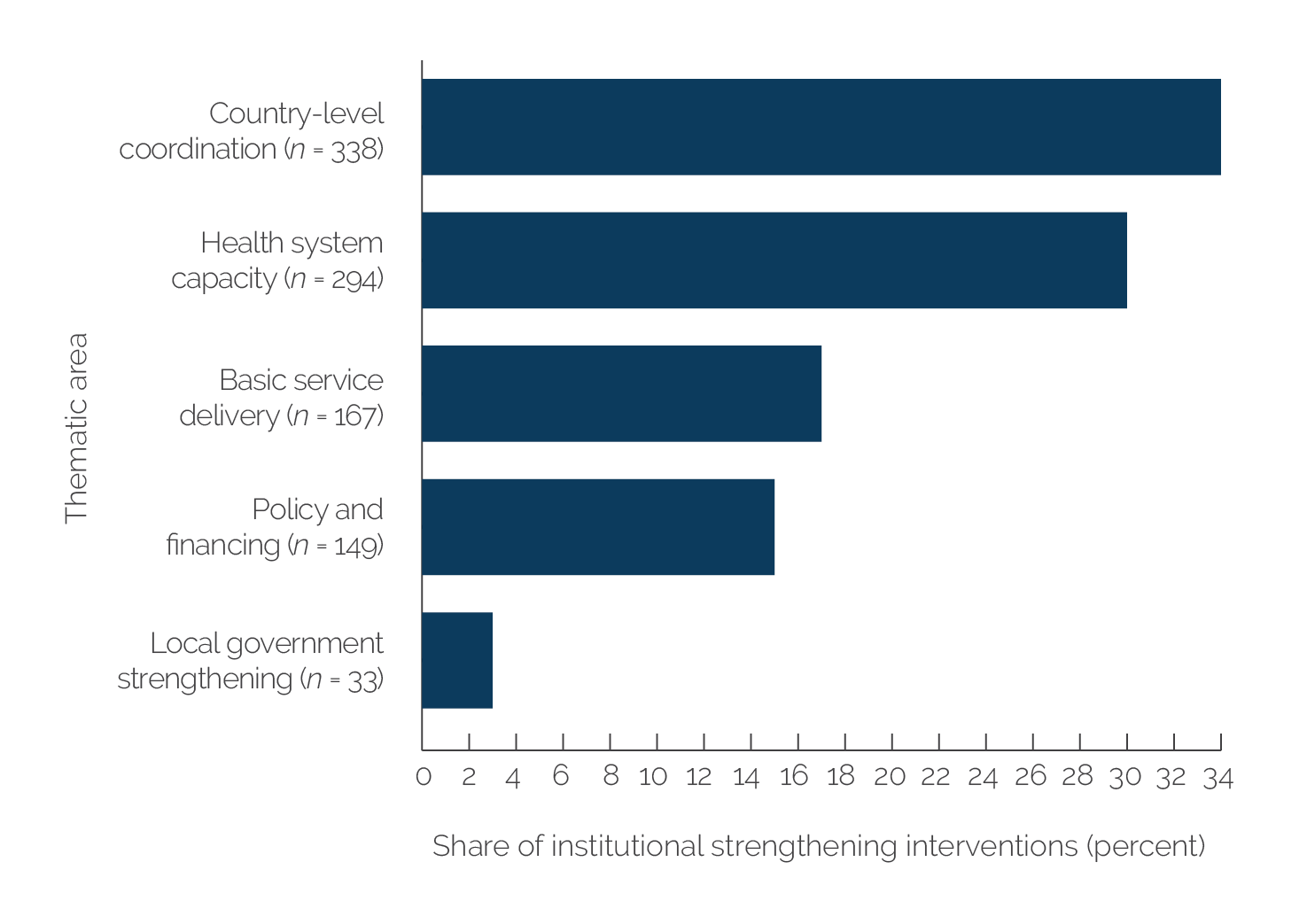

Integration of Support for Institutional Strengthening and Recovery

The integration of institutional strengthening in the COVID-19 response framework emphasized the importance of starting to build longer-term preparedness capacities from the early emergency response. Early institutional strengthening covered more than 90 percent of countries and focused on basic capacities for the immediate crisis, such as strengthening multisector coordination, surveillance, laboratories, remote learning structures, and social registries (box 2.5), with the portfolio analysis showing particular attention to institutional strengthening in FCS countries and countries with regional project support (appendix B). Support commonly went to early efforts seeking to improve coordination and health systems at the national level. Less attention in the early response was on strengthening local government systems and improving policy and financing (figure B2.5.1). The emphasis on institutional strengthening in the World Bank’s COVID-19 response brought the advantage of a longer-term systems rebuilding focus into the COVID-19 emergency, which has not been seen in past emergencies, such as for avian influenza. Other evaluations of COVID-19 responses note that institutional strengthening has so far been limited and requires further emphasis to sustain efforts (Johnson and Kennedy-Chouane 2021).

World Bank projects for the COVID-19 response often planned to help address the relief stage and to provide some support for restructuring systems. For example, in health, World Bank project support was for laboratory equipment and training and strengthening laboratory networks. World Bank teams used analytic work and existing projects to help countries plan next steps to strengthen health systems (the Philippines, Senegal, Tajikistan, and Uganda); however, these efforts remain at an early stage. Some countries, such as India and Tajikistan, have also been supported to reconfigure supply chains. In education, projects planned remote learning, which also included safe reopening of schools (Djibouti, Senegal, and Uganda), but learning losses will need to be addressed. In social protection, projects supported emergency cash transfers and systems strengthening, building on lessons from past crises (World Bank 2012). This support has started to expand public health functions, although much attention has gone to helping manage continued cycles of emergency with waves of COVID-19 infection.

Box 2.5. Examples of Institutional Strengthening Support in COVID-19 Response

Country-level coordination: support to national and subnational COVID-19 planning, multisectoral coordination, emergency operation units, assessments to enable coordination, operating procedures across sectors and actors, and online tracking of partner contributions

Health system capacity: support to health referral systems, human resource planning and development, use of geographic information systems to track diseases, improvements to coordination of surveillance and reporting systems, and laboratory quality

Basic service delivery: improvements to education services (such as pedagogy and building safety), and social protection systems, including social registries to cover vulnerable groups such as migrants

Policy and finance: policies to protect women and children, disaster and risk mitigation policies, expenditure reviews in human capital sectors, and costing of education sector reform needs

Local government strengthening: information and communications technology platforms for local government, community disease surveillance, expenditure management and budgeting processes to improve service delivery, delivery of essential services (waste management, electricity, and water), and municipal performance grants for civil works.

Figure B2.5.1 shows areas of early institutional strengthening support.

Figure B2.5.1. Areas of Early Institutional Strengthening Support

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio.

Note: Interventions in the chart are based on 253 projects coded for the evaluation. The number of coded interventions for institutional strengthening support is 981; the number of projects is 253.

Education and social protection support strongly emphasized strengthening digitalization (more than 80 percent of projects), converting systems and business models to digital technology, often building on work before COVID-19. From the relief stage, a key part of institutional strengthening was support for digitalization (66 percent of projects addressed digitalization, and 40 percent of innovations identified included digitalization), especially in FCS countries. In health, 59 percent of projects planned digital support, often for surveillance or case management (appendix B). Digitalization was expanded quicker where it could build on early foundational work before COVID-19, which was often the case for social protection, where there had been years of sustained investments countries made in creating national identification systems, digital payments systems, and integrated management information systems and social registries (such as in Brazil, Morocco, Senegal, Türkiye, and many other countries). In some countries, such as Senegal, digitalization actions were anchored in national development improvements. The evaluation could not assess the effectiveness of digital solutions to support outcomes. Examples of digitalization include the following:

- In education, countries supported television, radio, and online pedagogy resources for student learning. In Honduras, this included packages for children and parents to follow up on television and radio classes. India developed a digital platform for teacher training. Support of Education Technology thematic group helped rapidly scale up digital education solutions across countries from early in the COVID-19 response.

- In health, countries supported health information systems, contact-tracing applications, and digital surveillance. Mozambique, the Philippines, and Tajikistan developed digital tracking systems for vaccine rollout. In Tajikistan, health sector assistance enabled information hotlines and electronic supply chain management.

- In social protection, countries supported expanding digital beneficiary databases and payment systems. India and the Philippines strengthened their national identification systems, with links to digitalized payments for social benefits, social registry data on vulnerable groups, and data on migrant laborers. Djibouti supported an online platform for tracking food vouchers.

Countries do not yet have strategies that will help them develop more resilient systems and sustained capacities for better crisis response preparedness. The needs for capacity building to sustain COVID-19 investments are vast and fall across sectors—health, education, social protection, agriculture, and so on. Case studies and regional project analyses suggest that countries with regional disease-focused projects (such as Senegal and Zambia) often already had approaches for building public health preparedness, which were being developed before COVID-19. Incipient World Bank strategies to help prioritize investments arise from World Bank papers and recent work, for example, in health, social protection, and education (Barış et al. 2021; World Bank 2020e; World Bank Group 2021a, 2021b). Analysis of the cost-effectiveness of interventions fell outside the scope of this evaluation, although it may be useful to optimize the use of resources in the future. Few projects considered the efficiency of scarce resources in the crisis response.

- The human capital data on investment before COVID-19 was coded as part of a separate Independent Evaluation Group analysis. The human capital data cover Health, Nutrition, and Population; Social Protection and Jobs; and Education Global Practice projects between July 3, 2014, and January 15, 2020 (World Bank, forthcoming). Interventions to support human capital in countries before COVID-19 were reviewed in six areas: (i) essential health services (child survival and maternal mortality and improved equitable health access); (ii) critical health services (improved pandemic preparation capacity); (iii) protecting the vulnerable (connecting workers to jobs, expanded social program coverage, improved job skill readiness, improved targeting of lowest quintile, increased birth and social registration, and integrated social protection systems); (iv) ensuring child welfare and social services (inclusive education, learning outcomes, quality of teaching, school environment, early childhood development, and stunted growth of children); (v) gender (fertility and adolescent pregnancy, gender-based violence, female higher education and science, technology, engineering, mathematics enrollment, and female labor participation); and (vi) digitalization (information and communication technology policies, information and communication technology for better targeting and for quality service, and digital skills). The total number of areas supported in a country before COVID-19 was used to identify countries with different levels of human capital support by quartiles: 1 (very low), 2 (low), 3 (high), and 4+ (very high). The analysis includes 80 countries in the evaluation portfolio with available data on human capital support before COVID-19.