IFC’s and MIGA’s Support for Private Investment in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Situations

Management Response

International Finance Corporation and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency Management Response

International Finance Corporation’s (IFC)and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency’s (MIGA) managements thank the Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) for the report The International Finance Corporation’s and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency’s Support for Private Investment in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Situations, Fiscal Years 2010–21. This evaluation topic is highly relevant, considering IFC’s and MIGA’s ambitious targets in fragile and conflict-affected situations (FCS) and International Development Association (IDA) countries, as outlined in the 2018 capital increase package of IFC, and the World Bank Group fragility, conflict and violence (FCV) strategy for fiscal years (FY)20–25. It also presents an opportunity to reflect on IFC’s work in FCS to date and to inform implementation of IFC 3.0 and the FCV strategy. For MIGA, support for FCS has been an important area of concentration in its series of strategies, and is one of the strategic focus points of its strategy and business outlook (SBO) for FY21–23.

IFC and MIGA managements appreciate the engagement with IEG teams during the review of the draft report. Management would like to highlight that the extremely tight turnaround for IFC and MIGA’s corporate review and the formulation of the management response has put a significant strain on IFC and MIGA, which is very unfortunate for an evaluation of such strategic importance.

Management also notes that management and IEG collectively committed to the reform of the Management Action Record last September. IEG recommendations backed by solid evidence play a critical role in influencing the Bank Group’s directional change to contribute to outcomes that matter. Selectivity in recommendations and alignment with strategic priorities were among other key principles of the reform. These reform principles could have been better applied to the recommendations of this evaluation.

International Finance Corporation Management Response

Overall, IFC management finds that the report presents an informative summary of IFC’s performance in FCS contexts, including investment, advisory, and development effectiveness results and their underlying drivers. The report also draws out useful observations and findings that confirm IFC’s approach to scaling up business in FCS markets. In fact, as highlighted in the report, IFC has already begun implementing measures aligned with those proposed by IEG, beginning with the adoption of the IFC 3.0 Creating Markets Strategy, the institutionalization of the upstream business model, and the Bank Group FCV strategy.

For example, IFC management agrees strongly with the report’s assessment that the ability to substantially increase investments in FCS countries requires continuous recalibration of the business models and development of new tools and approaches. Along those lines, IFC has recalibrated its business model and deployed several new approaches and instruments that have been either specifically developed for or adjusted to respond to the challenges of operating in FCS markets. In addition to those summarized on in the overview of the report, the following should also be considered:

- Institutionalization of IFC’s systematic approach to upstream project development and market creation, particularly in FCS and IDA countries, including dedicated staffing, differentiated incentives, and modified targets to encourage delivery of higher-risk, and long-gestation programs.

- New diagnostic tools, such as Country Private Sector Diagnostics (CPSDs) and IFC Country Strategies. A guidance note on incorporating FCS considerations into private sector diagnostics is in development.

- Launch of the Anticipated Impact Measurement and Monitoring framework. This framework was modified in FY20 to apply FCS considerations and weighting to projects in FCS.

- New risk procedures, including (i) the FCS and IDA Risk Envelope—an allocation for high-impact projects beyond IFC’s standard risk tolerance; and (ii) the Contextual Risk Framework—a key diagnostic framework used to better understand country context, risks, and fragility drivers to inform strategy and operations in FCS markets.

- The IDA Private Sector Window (PSW) and other blended finance resources, which use concessional financing to help rebalance risk-return for high-impact first-of-their-kind projects in FCS. These tools have been either specifically developed for or adjusted to respond to the challenges of operating in FCS markets. With respect to the slow deployment of the PSW, significant progress has been made since the 18th Replenishment of the International Development Association, as noted in the management comments on the recent IEG evaluation of performance on the PSW. PSW deployment has increased, reaching $496 million out of the 19th Replenishment of the International Development Association by the end of FY21, and the pipeline for the Replenishment exceeds the envelope allocation of $1.3 billion.

- Explicit recognition of the priority to increase private equity and venture capital funds in IDA and FCS markets under IFC’s equity strategy.

- New platforms, including the Conflict-Affected States in Africa (CASA) initiative, an important, innovative program to enable IFC’s engagement in African FCS countries. CASA is a donor-funded, IFC-implemented platform that supports IFC’s advisory projects across 13 African countries. It has facilitated investment climate reforms; advised close to 3,000 companies, government agencies, and other entities; has supported over 115,000 farmers; and helped mobilize investments of more than $942.4 million into FCS markets.

- The CASA Initiative has supported the growth of IFC’s footprint and broader private sector development activities in FCS countries through three key pillars: funding IFC advisory services projects, provision of operational support in the field to AS projects and investment operations, and knowledge management. Moreover, CASA was independently reviewed by both IEG (in the first quarter of FY21) and an external reviewer, and received a very positive assessment, indicating that the flexible financing mechanism, support in the field, and innovative thought leadership contribution, have been a catalyst to success in FCS countries.

- Enhanced focus on staff learning, with a dedicated course on tools for investing in FCS and low-income countries (LICs), aimed at presenting the range of IFC tools and instruments available to staff working in these environments. To date, over 80 staff have been trained.

Besides the strategic placement of the new tools and resources, IFC management has also implemented an organizational realignment specifically designed to increase management attention for FCS operations. Notably, IFC (i) split the Africa region into three subregions, adding a third regional director; (ii) created a new Regional Vice Presidency covering the Middle East, Central Asia, Turkey, Afghanistan, and Pakistan; and (iii) integrated a part of the World Bank’s Equitable Growth, Finance, and Institutions Global Practice back into IFC’s operations. The latter aligned resources and expertise in support of IFC 3.0, including the expansion of the IFC Upstream program, and aims to enhance the development impact of Equitable Growth, Finance, and Institutions projects, while keeping collaboration and coordination with the World Bank in specific areas, including diagnostics such as CPSDs. Although full benefits of these changes are yet to be seen as the report indicates, IFC management is confident that the new configuration will allow us to enhance our support for FCS countries.

IFC management understands that ramping up operations in the most challenging markets requires sustained effort and a dedicated shift in resources. As stated in the FY22–24 IFC SBO, as the pandemic unfolded, IFC saw initial higher levels of demand from middle-income countries, after the evolution of the health and economic crisis, with IDA FCS countries leading use of short-term finance (STF) instruments. IDA FCS is a core priority for IFC, and IFC is redoubling its efforts to grow the IDA FCS pipeline and deploying the full range of instruments. We are beginning to see growing demand for long-term finance (LTF) in IDA and FCS markets, including 48 percent of Upstream pipeline in 17th Replenishment of the International Development Association (IDA17) and FCS, and $5.3 billion in IFC’s LTF investment pipeline to support IDA17 and FCS as of the end of FY21. For FCS specifically, FY21 saw robust aggregate IFC delivery (including STF, LTF, and mobilization) at $4 billion (see the “IFC investment volumes in FCS” section and figure MR.2).

Enabling environment for the private sector in FCS markets: In committing the Bank Group to scale up its efforts in FCV environments, the Forward Look and the Bank Group FCV strategy recognized that progress on the policy and regulatory reform agenda is a critical condition to maximizing finance for development and unlocking private sector activity. At the heart of this is the Cascade approach—the shared understanding that Bank Group institutions must work together to put in place Upstream reforms to address market failures through country and sector policies, regulations and pricing, and institutions for private sector activity to grow. Although there has been considerable progress on this front, particularly in FCS countries through joint work on CPSDs, IFC Country Strategies, Country Partnership Frameworks, Upstream work and Development Policy Operations, and the implementation of the IDA PSW, more needs to be done to improve policy and regulatory frameworks to unlock the private sector in FCS markets. As envisioned in the Approach Paper, it would have been beneficial if the report had analyzed how the work in this area had progressed through the Cascade approach, and enabled IFC (and MIGA) to catalyze private investment and supported this agenda to date.

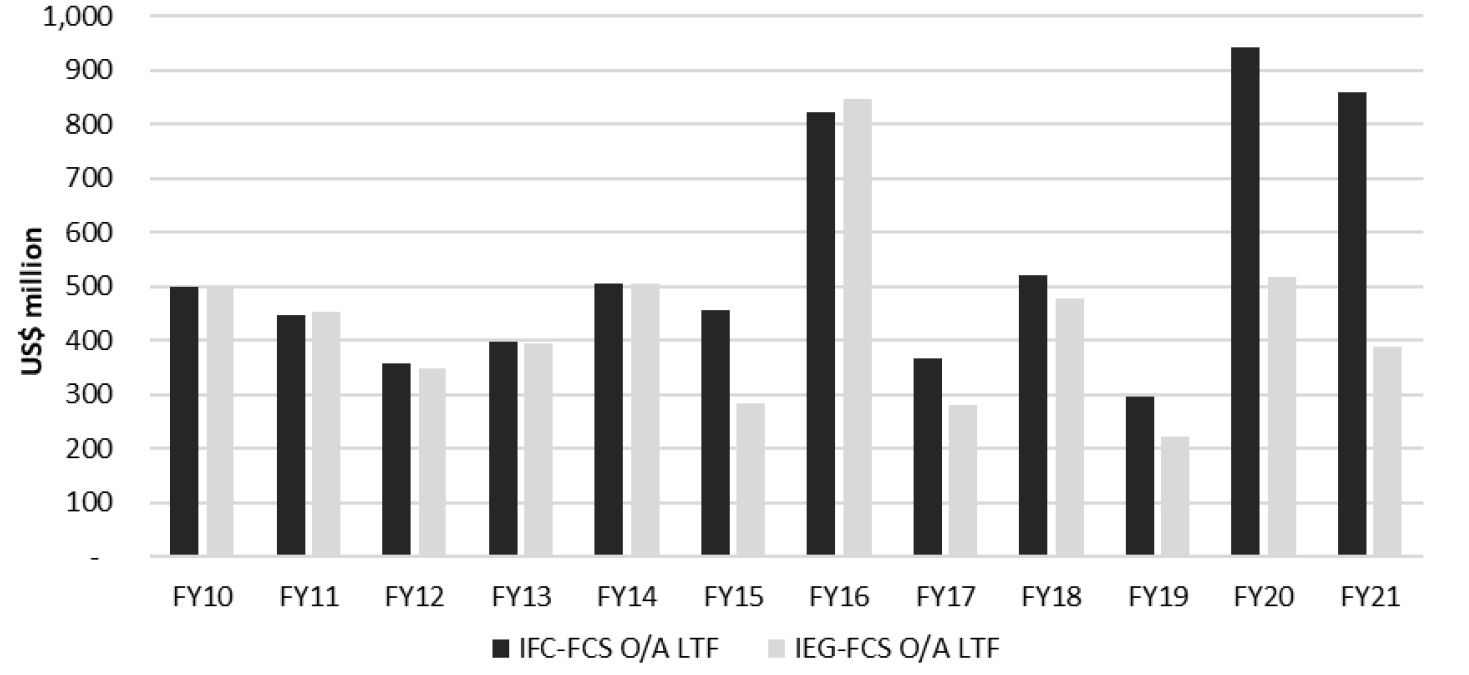

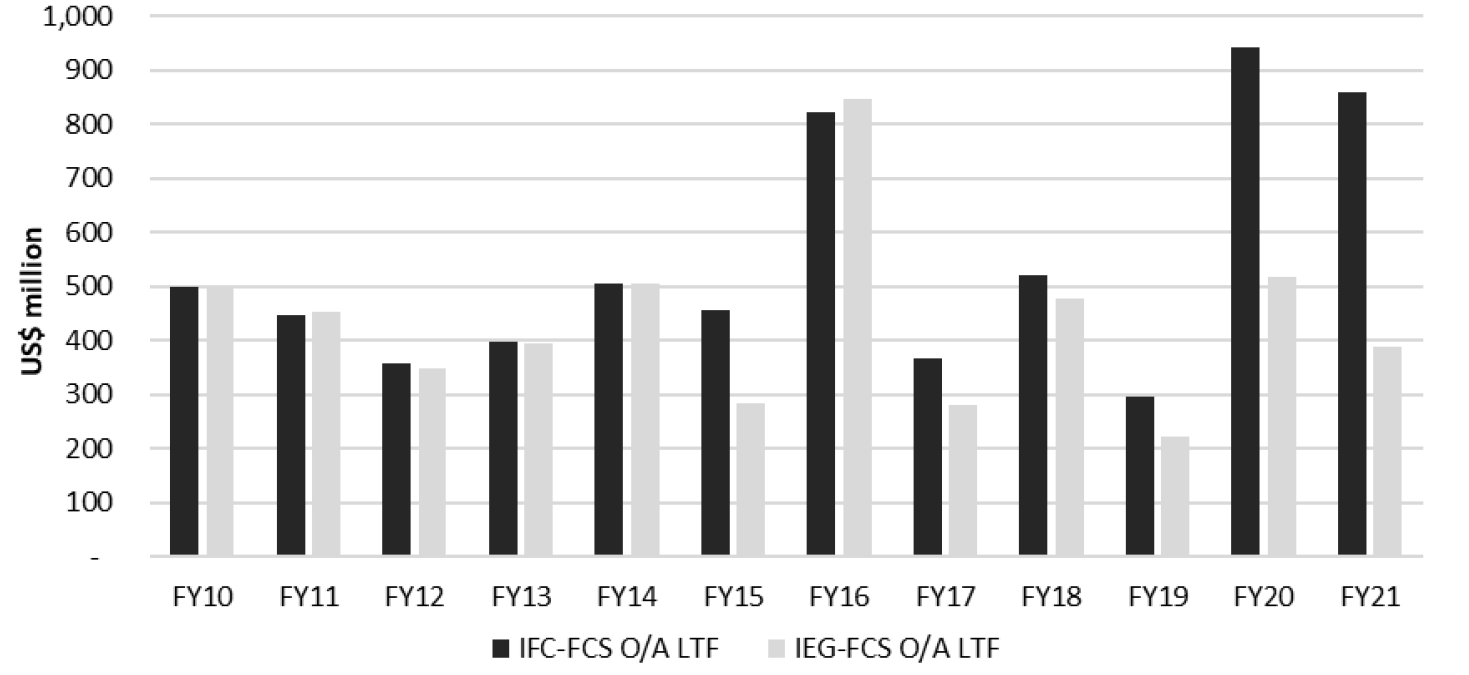

IFC investment volumes in FCS: IFC management thanks IEG for their explanation of the differences in the categorization of FCS markets used by IEG and those employed by MIGA and IFC for operational and reporting purposes.1 In particular, appendix G “IFC and MIGA Portfolios” is very helpful. As mentioned, the differences between IFC and IEG’s analysis (see figure MR.1) arise primarily from the following:

- Differences in the definition of FCS. IEG uses the World Bank’s harmonized list prior to FY20, and the list established by the Bank Group FCV strategy from FY20. IFC extends the list by including countries that graduated from the World Bank list in the past three years. The rationale for the approach is associated with IFC’s strategic intent to support projects in countries that may be transitioning through to graduation from FCS status, when conditions are still fragile and there are still considerable political and economic uncertainties, and

- The treatment of regional and global projects in the IFC FCS portfolio. For added transparency, figure MR.1 below provides a breakdown of IFC own-account LTF commitments in FCS using IEG’s methodology and that used by IFC in reporting. According to IFC’s data, IFC reached record investment volumes—$942 million and $861 million of own-account LTF commitments in FY20 and FY21, respectively. In FY20 and FY21 alone, the gap between IEG and IFC’s data totaled $898 million, with $521 million attributed to regional projects, $246 million attributed to FCS definitional differences, and the rest attributed to other factors including differences in data sources and the definitions of STF and LTF.

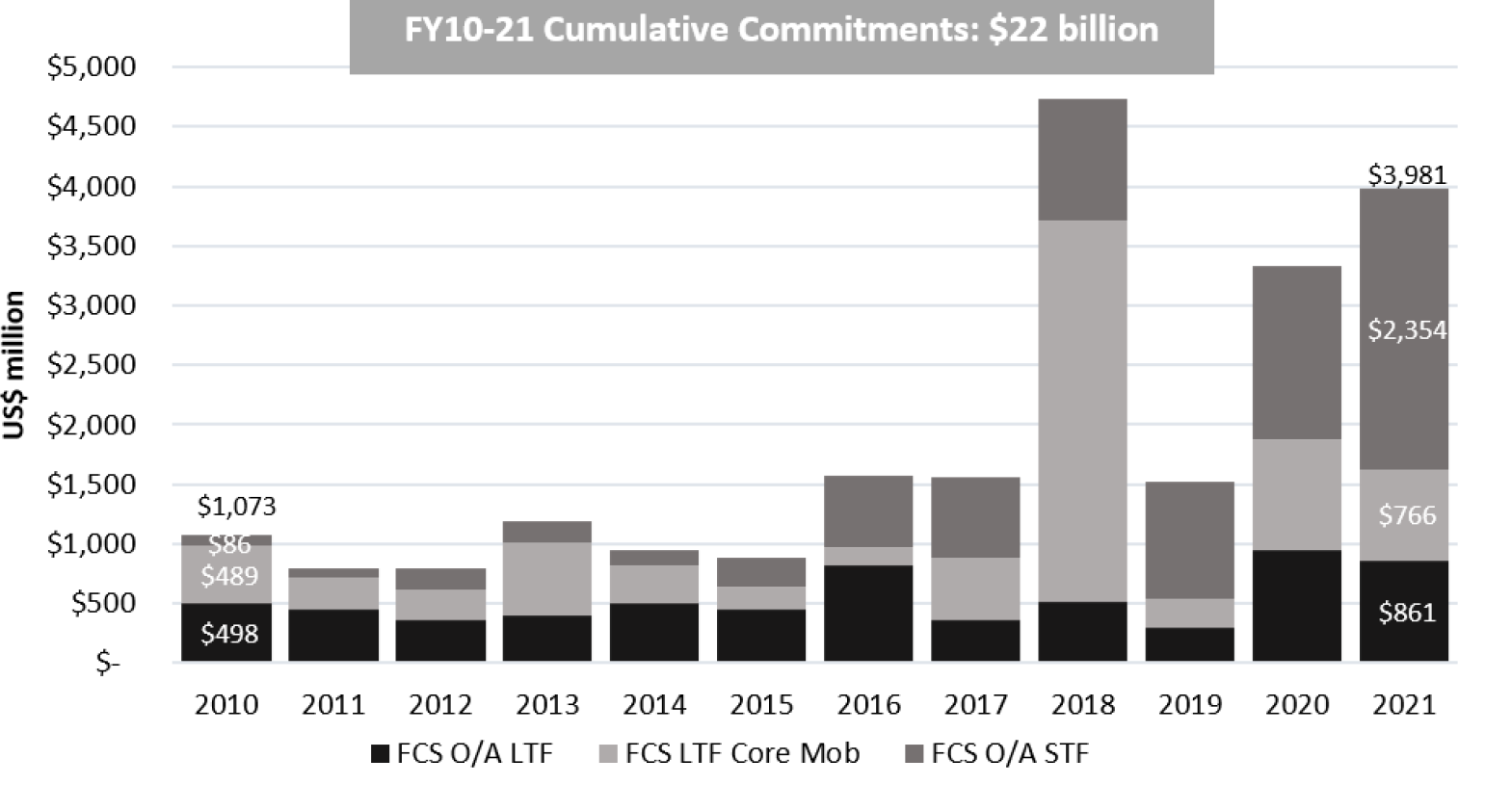

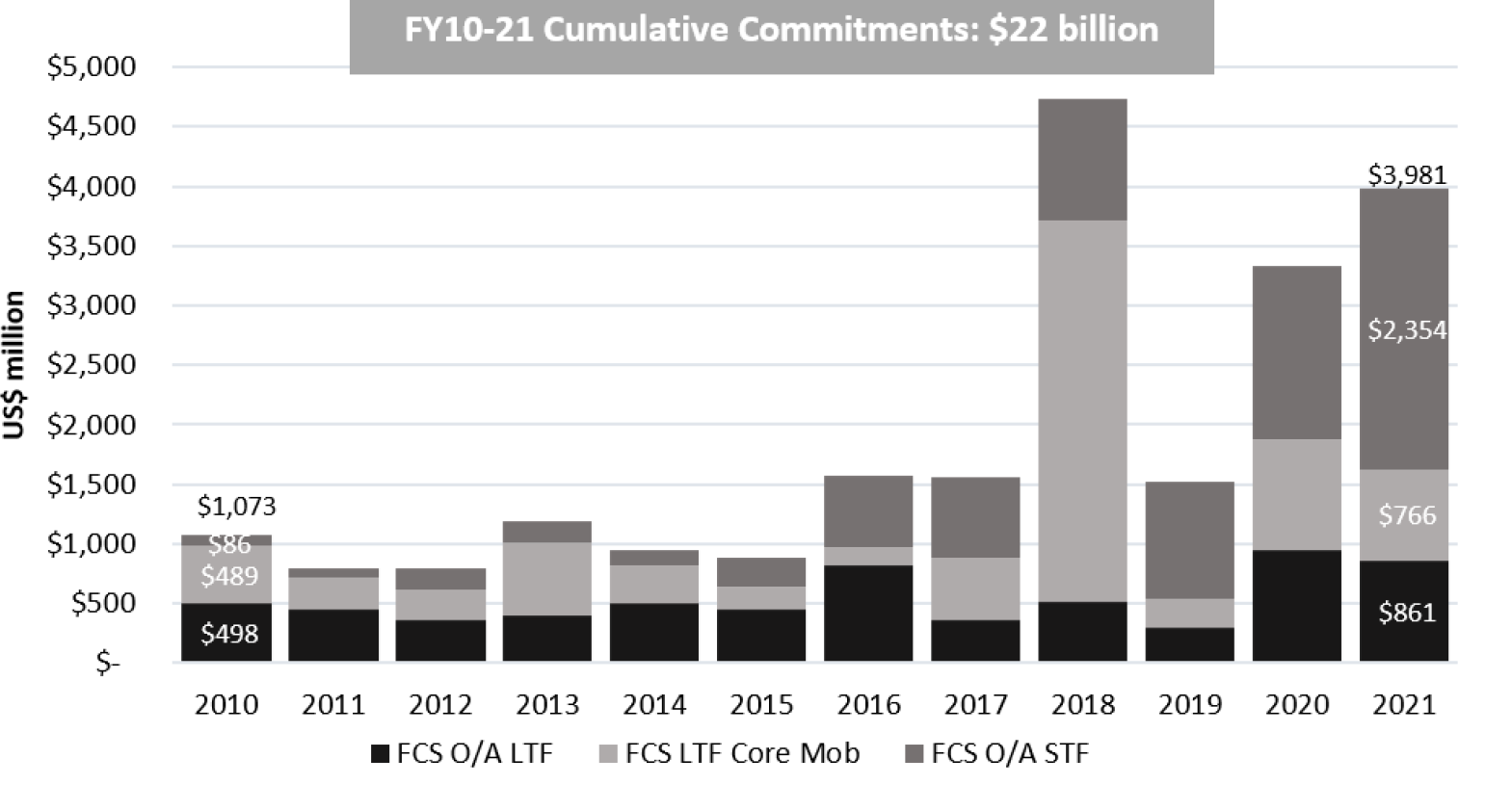

Beyond the methodological differences, however, IFC management is concerned that the report understates the magnitude of IFC’s delivery in FCS countries over the period by failing to aggregate IFC commitment volumes across all business lines—own-account LTF and STF, and mobilization. Cumulatively, over the period FY10–21 IFC invested over $22 billion in FCS markets (figure MR.2). In addition to the $6.5 billion in own-account LTF, IFC mobilized $7.9 million for FCS countries, achieving a mobilization ratio of 1.06 times. STF has been a critical vehicle for IFC’s support to FCS clients, with $8 billion deployed over the period. Measuring only IFC’s investment commitments in FCS also may not do justice to reflect IFC’s full engagement in FCS since advisory and Upstream work are often most relevant interventions for the most fragile countries. Advisory services play a critical role in IFC’s delivery in FCS by initiating the work on policy and regulatory reforms together with the World Bank, and the public and private sector players. IFC’s expenditure over FY10–21 has amounted to $505 million. IFC management fully agrees that more work needs to be done to scale IFC’s delivery in FCS and to keep IFC on the trajectory to meet the 2030 capital increase targets. However, an increasing trend is clear despite the operational challenges related to the coronavirus (COVID-19) and unprecedented levels of setbacks and increased conflict and fragility. Many FCS markets experienced conflict and fragility in the past two years leading, in some cases, to suspension of Bank Group’s operations. Other multilateral development banks and development finance institutions trying to focus on FCS find similar business development constraints.

Figure MR.1. IFC Own-Account Long-Term Finance Commitments over FY10–21: IFC Reported versus IEG Reported

Source: International Finance Corporation

Note: FCS = fragile and conflict-affected situations; IEG = Independent Evaluation Group; IFC = International Finance Corporation; LTF = Long-Term Finance; own-account = own-account

Figure MR.2. Aggregate IFC FCS Commitments (Own-Account LTF, Core Mobilization and STF)

Source: International Finance Corporation

Note: Core Mob = Core Mobility; FCS = fragile and conflict-affected situations; IEG = Independent Evaluation Group; IFC = International Finance Corporation; LTF = Long-Term Finance; own-account = own-account; STF = Short-Term Finance

Incentives and staffing: IFC welcomes the report’s focus on incentives and staffing. Increasing staff presence both in and near FCS locations is an integral part of the implementation of the FCV Strategy. In recent years, IFC has taken deliberate steps in this direction, including increasing the number of staff based in FCS locations from 89 in FY19 to 147 as of the end of FY21, and growing the number of offices in FCS markets from 18 in FY19 to 24 as of end of FY21. In FY19–21, IFC opened 8 new offices in Sub-Saharan Africa, of which 5 were in FCS. IFC’s Corporate Awards continue to be an effective tool in recognizing the significant contributions of staff in challenging FCS projects across the institution. Recognizing staff working in FCS has been a key focus of these awards: in FY20, approximately 35 percent of the awards were given to teams working on projects in FCS locations. Similarly, of the 30 staff who received IFC Top 30 Individual Corporate Awards in FY20, 13 (or 43 percent) had worked on projects related to or in FCS locations. Given the importance of upstream work in FCS locations, IFC’s new Upstream Milestone Awards recognize noteworthy efforts and achievements in upstream projects: major external milestones, conversions from upstream effort to mandated investment projects, disciplined project droppage when appropriate, and collaboration across departmental lines that goes above and beyond traditional joint projects. IFC’s Human Resources Strategy FY20–22 puts forward the following priorities: (i) cultivating a high-performance culture in alignment with corporate and individual objectives; and, (ii) facilitating career frameworks, recognition, and financial rewards (including through awards programs) in alignment with the Bank Group FCV strategy. Although designing appropriate incentives for staff to work in FCS can be challenging, IFC management will maintain efforts to adapt our incentives to driving behaviors that will increase the effectiveness and engagement of all IFC staff, ultimately leading to better operational delivery—especially in priority markets—and successful implementation of IFC 3.0.

Cost of doing business: IFC management appreciates IEG’s analysis of costs incurred to IFC for FCS engagement. Indeed, higher expenses, such as greater operating costs for appraisal and supervision, may disincentivize building the FCS pipeline. Although IFC management agrees with the overall message that the costs are indeed high, IFC uses a different methodology than IEG for assessing the cost of doing business in FCS. As such, IFC management cannot verify the numbers presented by IEG, which limits IFC’s ability to comment on some of IEG’s analysis. However, IFC management does closely monitor the cost of doing business in FCS and would be open to learning more details of IEG’s methodology.

Recommendation 1: IFC and MIGA should continue to review their financial risk, make more explicit the implications of IFC’s portfolio approach for FCS, and enhance capabilities to address nonfinancial risks to ensure they align with achieving business growth targets and impacts in FCS. In principle, IFC management agrees with the recommendation to continue to review financial risks, to make the implications of IFC’s portfolio approach for FCS more explicit, and with the need to address nonfinancial risks to ensure they align with achieving business growth targets and impacts in FCS markets. In line with these efforts, IFC adopted the Portfolio Approach to strike the balance of lower-risk projects and a higher-risk–adjusted return and more IDA and FCS exposure where risk-adjusted returns on capital for loans are significantly below IFC average. IFC’s Portfolio Approach aims to achieve high development impact and financial sustainability over the portfolio as a whole, allowing the corporation to take greater risks on individual investments while managing the overall balance sheet. Anticipated Impact Measurement and Monitoring, the quantitative metric for measuring development impact—alongside an agreed financial sustainability metric, risk-adjusted return on capital —underpins the Portfolio Approach, allowing IFC to make its traditional balancing of development impact and financial sustainability in a more refined, consistent, and transparent manner. IFC management is also aware of the high nonfinancial risks that impact IFC’s investments in FCS and has developed a range of tools to create greater awareness of these risks and mitigate them, including the Contextual Risk Framework, expanded Environmental and Social advisory services and enhanced approaches to addressing conflict sensitivity in private investments. Although it may be too early to assess their effectiveness since many of these tools are new or have been expanded or enhanced recently, IFC management is committed to continued implementation of these efforts and will continue to report the progress on respective reporting platforms.

Recommendation 2: To focus on the development of bankable projects, IFC and MIGA should recalibrate their business models further, client engagements, and instruments to continuously adapt them to the needs and circumstances of FCS and put in place mechanisms to track their effectiveness for real-time learning. IFC management agrees on the spirit of the recommendation that an intentional and measurable approach to developing bankable projects in FCS is of paramount importance. The recognition that a proactive approach to both creating markets and facilitating bankable projects to attract new private investment in strategic sectors has been at the heart of the IFC 3.0 Strategy. This strategy is designed to support growth and job creation, especially in FCS markets with the importance of increased focus on early-stage engagements and collaboration across the Bank Group. To that end, IFC has been embarking on several initiatives.

- First, it launched its intentional approach to project development—IFC Upstream. IFC Upstream fits in a seamless continuum that seeks to harness Bank Group–wide engagement to create markets and mobilize private capital. The World Bank strengthens the investment environment of client countries and IFC supports private sector development; IFC Upstream connects these activities by creating a line of sight to bankable investments and mobilization. IFC has embedded this approach into the organizational structure, including the creation of global and regional upstream units that are fully integrated into IFC industries. Staffed with some of IFC’s most experienced personnel, including new dedicated hires for IFC Upstream, the upstream units draw on a range of diagnostic tools to help IFC identify, assess, and prioritize new market creation opportunities. Upstream has also employed a robust governance structure to ensure resources are efficiently allocated and activities are strategically aligned. For example, the Quarterly Upstream Pipeline Review Meetings (37 held in FY21) allow for continuous and dynamic prioritization of resources with appropriate project redirection in real time. Also, timely action and quality reporting on project droppages are systematically governed to learn project specific lessons related to country, sector, project design, and management. As of June 30, 2021, 48 percent of the Upstream own-account pipeline was in IDA17 and FCS and 20 percent in LIC-IDA17 and IDA17-FCS.

- Second, through a Funding Needs Assessment process, which has engaged the institution in a strategic planning process ensuring that IFC aligns its fundraising targets with strategic priorities and 2030 commitments, IFC management repurposed its country-driven budgeting approach, integrating the country-driven budgeting already in place for Upstream and the Funding Needs Assessment into a single exercise covering both upstream and advisory, enhancing the links among strategy, resources, and operational delivery. Country and Regional planning ensures strategic priorities drive activities and enable close collaboration with the World Bank. Also, to address the resource implications of scaling up in FCS, IFC is enhancing partnerships with nontraditional investors such as the Rockefeller Foundation to advance distributed renewable energy solutions in Sub-Saharan Africa and select other regions to work with Upstream on project preparations for private sector clients and governments. Another strategy to reduce costs while creating more opportunities is for IFC to co-invest with private sector clients to prepare, advance, and develop projects. Under the new Collaboration and Co-development Upstream tool, IFC can provide early-stage risk funding and undertake joint work with prospective private sponsors and companies through cost-sharing of specific limited scope studies in return for certain future co-investment rights or financing rights. Such early project development via Collaboration and Co-development is expected to deliver on more South-South and regional cooperation in FCS and LICs, especially in the real sector economy.

- Third, IFC continues to evolve its tools, instruments, and ways of engaging with clients. As mentioned earlier, IFC management launched a number of tools that are either focused or adapted to the FCS context. For example, IFC launched the Africa Fragility Initiative, a five-year program to support delivery of responsible private sector development in 32 countries in Africa. Africa Fragility Initiative is the successor and builds on the experience of IFC’s CASA Initiative, which ran from 2008 to 2021, and it will provide flexible and catalytic funding, a presence in the field, and strategic collaboration. Finally, IFC continues to identify new and innovative approaches such as the recently established Risk Institute, an initiative led by the IFC Credit Department in collaboration with regional investment teams. The Risk Institute is designed to deliver sector- and region-specific workshops targeting finance executives of Small and Medium Enterprises in FCS and IDA countries, and it aims to help them assess their companies’ readiness for investment by IFC and other development finance institutions or both. In this regard, IFC will continue implementing the above and further efforts to increase bankable projects in FCS by continuously adjusting its business models, client engagements, and instruments for these countries.

Recommendation 3: IFC and MIGA should identify and agree to FCS-specific targets in their corporate scorecards to focus their efforts and track progress in implementing the Bank Group FCV strategy for the private sector. The current use of key performance indicators comingling LICs, IDA, and FCS country groupings may dilute the focus on FCS and FCS-specific topics. Related to this, the World Bank, IFC, and MIGA should harmonize their definition of FCS and use a single FCS list to enhance transparency, clarity, and comparability of reported data. IFC management would like to express concerns about this recommendation, and its subrecommendation. It has significant operational and reporting implications for IFC and MIGA, and indeed private sector development in those markets. The IFC capital increase commitments have a strong focus on FCS and include targets for IFC to reach 40 percent of own-account investment volume in IDA17 and FCS and 15 to 20 percent in IDA17-FCS and LIC-IDA17 by 2030. These commitments have been endorsed by IFC’s shareholders in 2018 and are reflected in the annual key performance indicators reporting to the Board of Executive Directors. These targets reflect IFC’s strategic focus on FCS as well as IDA and recognition that IDA, in particular LICs, share with FCS many characteristics and often face similar obstacles in attracting private investments. There is also a significant overlap between FCS and LICs, and only six countries classified as LICs are not FCS. In addition, most of the LICs have only recently graduated from the FCS status and remain quite vulnerable. Therefore, IFC management does not believe that these combined targets have diluted IFC’s focus on FCS and on poorest countries. Since the IFC capital increase targets were already in place during the development of the FCV strategy during 2019–20, they provided a foundation for the FCV strategy and were deemed effective to guide and monitor IFC’s engagement in FCS. Regarding the harmonization of the definitions of FCS, IFC made a deliberate decision to adapt the World Bank list to its operational context, and since FY15, IFC has used an expanded definition of FCS to include countries that graduated from the World Bank’s FCS list in the subsequent three years. There is a sound operational basis for this decision. This approach was taken to provide greater predictability for IFC’s operations teams and clients. It has enabled IFC to expand its tools, resources, and incentives to the countries that are just emerging from FCS status, but still face significant challenges in attracting private investments. At the time that countries graduate from World Bank’s FCS list, they are typically just emerging from fragility or conflict and in some cases later fall back into the FCS status. IFC can play an indispensable role in these countries by supporting their transition at this critical time and helping them stay on an upward developmental trajectory at the time when many are at high risk of reverting. Formalized in a Guidance Note within IFC’s Policy and Procedure Framework, IFC’s FCS definition has become a part of its DNA. It would be not only disruptive and difficult, but disincentivizing for the operations teams and IFC clients to adopt the World Bank’s FCS list.

Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency Management Response

MIGA thanks IEG for undertaking the evaluation The International Finance Corporation’s and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency’s Support for Private Investment in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Situations, Fiscal Years 2010–21. MIGA is appreciative that IEG has taken into account in the final report some of MIGA’s observations. The evaluation comes at a critical time in the continued development of MIGA’s FCS work. Support for investments into IDA FCS is one of the strategic focus points of our SBO FY21–23. It also has been an important area of concentration in previous strategies. Moreover, the Bank Group FCS strategy stresses the significance of the private sector in contributing to sustainable development in FCS, including in the crucial area of job creation.

Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency’s Performance

The evaluation provides useful and helpful background information and observations. In assessing MIGA’s performance in FCS, MIGA would like to draw attention to the following points:

- MIGA’s business model is to provide guarantees for foreign direct investment (FDI); therefore, it is critical for the FCS evaluation to benchmark MIGA’s performance against FDI flows into FCS countries to provide the necessary context to assess MIGA’s work in FCS and to draw appropriate conclusions and recommendations. FDI into FCS has declined precipitously over the past 10 years, driven by low commodity prices, slow global growth, the outbreak of new conflicts and the intensification of existing ones, and most recently because of the worldwide pandemic. During that time, despite these serious challenges, MIGA’s guarantee volume in FCS has remained steady; indeed, MIGA’s guarantees as a percent of FDI flows into FCS have actually increased over the period. Based on IEG’s data in figures 1.2 and 2.2, MIGA’s guarantees over the last three years of FDI data (2017–19) was 2.25 percent of FDI inflows to FCS, a large increase from 0.62 percent of FDI inflows over the first three years of the review period (2010–12). Therefore, IEG’s statement on MIGA’s volume without “an upward trend” (15) should be assessed within the context in which MIGA operates and benchmarked against FDI flows. Seen relative to FDI flows into FCS, MIGA has actually significantly grown its portfolio over the period.

- Moreover, the report confirmed that “evaluated MIGA projects in FCS countries performed better than in non-FCS countries” (25). According to the report, “seventy-three percent (16 of 22) of evaluated FCS projects were rated satisfactory or better for their development outcome” against “64 percent…in non-FCS” projects (25). IEG confirmed the importance of the project sponsors’ experience, technical expertise, financial capacity, and knowledge of local conditions as critical factors in operating successfully in FCS. MIGA concurs that these traits have important ramifications for project design and project operation in difficult and uncertain environments. The report also illustrated relative success in FCS projects in Agriculture, Manufacturing, and Services sectors (82 percent) in FCS, compared with 68 percent in non-FCS countries. Successful projects benefited from MIGA’s partnership with foreign investors with technical expertise who often had a larger asset base and the ability to manage multiple risks in the FCS context.

Independent Evaluation Group Recommendations

MIGA appreciates IEG’s efforts to find useful recommendations. MIGA is working to deepen our ability to work more impactfully in FCS; we readily acknowledge that this is difficult and challenging work. In that context, we are keen to obtain IEG’s insights on figuring out what we could be doing differently to enhance our impact, including increasing our volumes in FCS countries.

With respect to the current recommendations, we believe that the recommendations could be more supportive of our objectives. Most of IEG’s current findings confirm what we already know, and the recommendations do not have a sharp focus nor a strong analytical evidence base for moving the needle toward the intended outcome of scaling up MIGA’s business for impact in FCS. Moreover, most recommended actions under recommendation 2 are already under implementation and reported in MIGA’s annual SBO update and our quarterly executive vice president report to the Board.

Independent Evaluation Group Recommendation 1

The first recommendation was to “continue to review their financial risk… and enhance capabilities to address nonfinancial risks to ensure they align with achieving business growth targets and impacts in FCS” (61). Furthermore, the recommendation states, “IFC and MIGA should continue to periodically assess that the risk frameworks, models, capital requirements and financial implications fully support the business growth objectives and targets of the institutions in FCS” (61). On nonfinancial risk, the recommendation said, “IFC and MIGA should assess and where needed, strengthen their capacity to address nonfinancial risks as they are a key constraint to developing bankable projects in FCS” (61).

Financial risks: Although the evaluation provides some information on MIGA’s well-developed financial risk management framework, the evaluation did not identify any specific gaps that would lead to recommending any changes. Indeed, the analysis in the report on credit and financial risk at MIGA in the FCS context is minimal and does not help the reader with insights into risk appetite or risk management. For example, the discussion on this topic for MIGA is limited to two data points, specifically, claims paid to date in FCS and pre-claims in FCS—both indicators point decidedly to the higher risks MIGA accepts in FCS. For example, the claims data indicates that during FY10–20, five of the seven claims that MIGA paid were in countries classified as FCS, an indication of the higher risks in FCS. Pre-claims among MIGA projects are also more frequent in FCS countries than in non-FCS, according to IEG, and while the report decides not to take this evidence into account on the grounds that these claims were not “driven by fragility or conflict,” MIGA would like to state that there is a strong correlation between elevated credit risk and the FCS categorization. Although “drivers” of pre-claims may be similar in FCS and non-FCS countries, the severity of those drivers and the lack of buffers to address them when they manifest are the reasons that projects in FCS countries are financially riskier than projects in non-FCS countries.

This track record of claims and pre-claims in FCS countries is also a recognition that MIGA is open for business in FCS. MIGA’s political risk insurance—composed of four points of cover—currency transfer restriction and inconvertibility, expropriation, breach of contract, and war and civil disturbance—is a flexible instrument and particularly well suited to the FCS context. Generally, there is no minimum risk rating that our business developers are required to observe to engage with clients to discuss investment opportunities in FCS countries. There is one exception: the cover we offer on currency transfer restriction and inconvertibility risk in countries where there are already exchange controls in place—that is, where the risk to an investor has already materialized and a claim would be triggered on day one if we were to offer this cover to the client. However, other than that situation, MIGA can be open for business with its political risk covers in FCS markets. In part, our ability to offer these covers across FCS countries reflects MIGA’s carefully crafted framework to mitigate financial risks in its FCS business. We do this through three main mechanisms: first, access to the IDA PSW; second, MIGA’s ability to actively reinsure its guarantees in the reinsurance market; and third, our impactful pre-claims engagement in projects when issues develop. These three risk mitigants, along with our deep experience in underwriting projects in highly risky environments, have allowed us, to date, to meet our mandate to work in FCS settings while also fulfilling our requirement, as articulated in our founding document, to manage our financial risks prudently.

It is also important to note that both data points, claims, and pre-claims in FCS, compared with non-FCS, are backward-looking; as risk managers, we cannot rely solely on backward-looking data in our decision-making frameworks. This point is especially pertinent at present, given the significant reversals in some prominent FCS countries, where MIGA (as well as the World Bank and IFC) has been active and where we now face challenges with the projects we have supported.

On other aspects of managing our financial framework—pricing and financial incentives to staff to work on FCS projects—the report does not provide evidence that these are barriers to our work. We, ourselves, rarely find our pricing prevents MIGA from working in FCS countries; on rewards, staff are given financial incentives (and also recognition) for working in FCS countries, through our annual awards program and through the performance system of the Bank Group.

Furthermore, MIGA had hoped that greater recognition would be given to exploring the implications for MIGA’s mandate, business model, and commitment to other strategic objectives of the implications of this recommendation. It is useful to underscore that MIGA’s mandate is underpinned by two objectives: (i) to meet our agreed strategic objectives, including scaling up in FCS, and (ii) to safeguard our financial sustainability. This approach facilitates MIGA’s objectives to serve all clients more effectively and efficiently to maximize our development impact, while maintaining a sound financial structure to ensure long-term sustainability in line with our founding convention (article 25), which requires MIGA to adopt prudent financial management practices. The development objective and the financial sustainability mandate reinforce one another. Without maintaining our financial strength, we put our future ability to deliver development impact at risk, especially in the most challenging country settings of FCS.

MIGA believes that the report would have benefited from giving greater prominence to MIGA’s mandate to ensure our financial stability and further consideration of the implications to our business of a potential higher level of claims that could result. For example, the report states that “MIGA’s claims ratio (0.07 percent of outstanding exposure) during FY15-20 is much lower than for Berne Union members overall (0.42 percent of exposure)” (48) from which the reader might logically infer that to grow FCS business MIGA should increase its willingness to accept a higher level of claims. However, there is no indication of what this would mean for MIGA’s business model, the implications for MIGA’s capital position, or financial standing with rating agencies. For example, the delivery of some of MIGA’s products requires that MIGA remain a “highly rated multilateral bank,” but would it be possible to sustain that designation with a level of claims comparable to Berne Union members? It would have been helpful if the IEG report provided analysis of this kind to make the recommendations more actionable and impactful.

It would also have been helpful to provide more granular comparator analysis, as was indicated in IEG’s Approach Paper to the evaluation, as to how other guarantee agencies, both in the development finance institutions community and in the private sector, are engaging in FCS and what lessons could be discerned from this analysis with respect to the management of financial risks; however, the report was limited to qualitative analysis and did not bring any insights beyond the observation that “the DFI’s [development finance institution’s] engagement in FCS remains fragmented and may lead to competition for a few bankable projects.” (53) The report presented activities of comparator institutions (such as Berne Union members) without careful review of the nature of these activities and the substantive differences between MIGA’s business model and the business model of Berne Union members. For example, the report compares MIGA’s share in the FCS market to national public investment insurers without noting that these institutions’ products are often backed by their national governments. No analysis is provided on the activities of private insurers.

Nonfinancial risks: IEG recommended, “IFC and MIGA should assess and, where needed, strengthen their capacity to address nonfinancial risks as they are a key constraint to developing bankable projects in FCS” (61). The recommendation would have been more useful if it had been more specific about the types of project risks in the FCS contexts that are critical and key constraints for doing business in FCS. Although the evaluation recognizes nonfinancial risks as a key constraint to developing bankable projects in FCS, IEG does not indicate which among the nine nonfinancial risks it identifies in the report are the most impactful regarding MIGA’s operations in FCS. IEG seems to suggest that thorough environmental and social (E&S) due diligence and capacity building, these nonfinancial risks will be overcome, but in MIGA’s experience, institutional weaknesses can overwhelm efforts at capacity building or even high-quality due diligence and hence result in the less than fully successful application of MIGA’s E&S standards at some stages of the project. Moreover, accepting less sophisticated clients can significantly increase the chance of having negative consequences (including E&S and reputational risk for the Bank Group) derived from these risks. The risk appetite statement in this evaluation did not explore these possible trade-offs in a way that would support helpful recommendations in this area.

In this context, it is useful to underscore that MIGA applies the same E&S Performance Standards to our projects in FCS as we do in non-FCS. We believe this is in line with our policy and guidance from the Board. In challenging settings, when needed, we will provide longer time periods for our clients in FCS to fulfill their obligations under the E&S Action Plan. In those instances, we may also provide greater support to clients, for example, through dedicated staff time and training to build their capacity and understanding. However, we will only bring a project to the Board for approval if we believe the project will meet the Performance Standards in the time period set out in the E&S Action Plan that MIGA agrees with the client and is embedded in our contract of guarantee.

IEG Recommendation 2

The second IEG recommendation is for IFC and MIGA to “recalibrate their business models, client engagements, and instruments” (61) for these countries to focus on developing bankable projects in FCS. MIGA agrees that the main obstacle to further supporting foreign investment into FCS countries is the lack of bankable projects. MIGA considers that for the second recommendation, it would be more beneficial to specify specific areas of recalibration in its business model, distinguishing between actions that are already in place to address the challenges and are showing promise and areas in which MIGA needs to take a new approach. For example,

- To continuously enhance collaboration on diagnostic and upstream work with the World Bank and IFC and to fully exploit synergies with IFC and the World Bank’s creating markets activities, MIGA has scaled up further its participation in CPSDs, Systematic Country Diagnostics, and Country Partnership Frameworks, and also in the new Country Climate and Development Reports, to identify and, work with the World Bank and IFC, to address impediments in business climates that constrain private sector activities as well as FDI. Indeed, MIGA’s focus, given its limited resources when compared with the World Bank and IFC, has been specifically targeted at FCS countries to ensure our collaboration, both in the Bank Group’s coordinated upstream work or downstream in joint projects, whether with the World Bank and IFC or both. MIGA has scaled up its staffing presence in the Africa region to be closer to developments in the field and is continuing efforts to look for opportunities where we could make a difference for our work in moving more staff closer to project locations. MIGA would also point to the close coordination in developing and implementing the PSW, which is helping to support MIGA’s work in FCS in particular and is a best-in-class example of coordination across the three institutions.

- Concerning the recommendation to use the full tool kit available, including the Small Investment Program (SIP), it is useful to recognize, as IEG itself acknowledges in the report (appendix E), that SIP projects, as is similar to non-SIP projects in FCS, require extensive analysis because of the high risk nature of SIP projects and limited client capacity. In fact, it is a bit puzzling as to why IEG singles out the SIP program for special mention in the recommendation, given that IEG concludes (appendix E) that “there is insufficient evidence on [the SIP program’s] overall impact on scaling up bankable projects” (95). Although IEG observes that the SIP program has not been used since FY17, it would have been more helpful to explain the main reason, which is that the small dollar value of a project does not necessarily correlate to a straightforward project. Indeed, although MIGA has supported many small projects since FY17, none of these was sufficiently straightforward to justify the streamlined procedures of SIP processing. IEG reached a similar conclusion in their own review of the SIP program as indicated in this report. In addition, it is important to note that MIGA’s operational team is already deeply into a wide-ranging review of the SIP and how MIGA could use the SIP in a more effective manner to support MIGA’s current strategic areas, including in IDA and FCS.

- For addressing the upfront costs of developing private sector projects and project preparation in FCS, MIGA has established the MIGA Strategic Priorities Program. This program is a common framework under which MIGA will administer all four of its trust funds. MIGA secured funding for two new trust funds in the first half of FY22, one of which is the Fund for Advancing Sustainability. This fund will help MIGA-supported projects to address E&S and Integrity risks and build the capacity of MIGA-supported projects to manage such risks. MIGA would also like to reference and support the innovation proposed in IEG’s report on the PSW (The World Bank Group’s Experience with the IDA Private Sector Window: An Early-Stage Assessment), which recommends, “in future, the PSW could be structured to allow funding of advisory services from a small part of its overall allocation” (World Bank 2021b, 28). MIGA would also welcome further support from IDA to address the resource implications of scaling up in FCS, as IEG recommends.

- For putting in place mechanisms to track implementation and effectiveness of these initiatives for real-time learning and course correction, MIGA’s ex ante impact assessment and corporate scorecard would give information about tracking the implementation. MIGA has successfully launched its ex ante development impact assessment tool, Insights on Managerial Performance and Competency Tool, which recognizes the special development role that private sector projects can bring to countries that are affected by fragility and conflict. MIGA’s corporate scorecard also gives real-time indication of pipeline development and project performance for any necessary course corrections.

The report does not seem to give MIGA an evidenced-based direction as to what areas of our work to address in the challenges we face in FCS. But MIGA certainly agrees there is more we could be doing on the client development and product work. Of course, MIGA is not standing still in these areas, either. As Board members are aware, MIGA recently launched a new trade product with IFC specifically targeted at FCS and IDA countries.

MIGA has been continuing its efforts, as outlined in the SBO FY21–23 and in recent quarterly executive vice president reports and the most recent SBO update, to use its full tool kit in IDA FCS including (i) continuing Bank Group collaboration and the Maximizing Finance for Development or Cascade approach; (ii) leveraging blended finance solutions to better manage financial risks, including the PSW and MIGA-specific Trust Funds, both of which are targeted to FCV settings; (iii) receiving approval and moving to implement a facility to help smaller clients meet MIGA requirements for E&S and integrity standards; (iv) enhancing the SIP for development impact; and (v) continuing innovation, including establishing an Innovation Forum across MIGA aimed at establishing a staff-led innovation process that will allow staff to participate in developing transformative ideas with a specific focus on our strategic areas of engagement. In effect, MIGA has been implementing these activities and is already tracking and reporting them through the annual SBO Updates and Executive Vice President reports.

In summary, the IEG recommendations pertaining to recommendation 2 mostly touch on areas where MIGA is already engaged, taking action, and reporting to the Board. We would be happy to discuss additional ideas with IEG where we see opportunities for doing more, especially in the product and client development space.

IEG Recommendation 3

The third recommendation advocates FCS-specific targets to be incorporated into scorecards to focus our efforts and track progress in implementing the Bank Group FCV strategy for the private sector.

It is useful to clarify that IFC and MIGA use the same list for FCS that the World Bank uses. The Bank Group Corporate Scorecard uses Bank Group commitment volumes in FCS based on the Bank Group harmonized definition. For MIGA (and IFC), the adjusted FCS definition—“countries on the applicable World Bank’s Harmonized List of FCS for a given year plus countries that have been on the harmonized list within any of the past three years”—is used in MIGA’s SBO and corporate performance monitoring. The use of this strategy-based definition is aligned with MIGA’s efforts to scale up its work in FCS in the following manner:

- It is harmonized with IFC, reflecting our efforts to work with IFC to increase business development and deal sourcing.

- The strategy-based FCS definition aligns with the private sector project cycle in FCS, which is, as pointed out in the IEG report, much longer than in non-FCS countries. Staff working on a project in an FCS country require a longer period to bring the project to contract signing and as a result a switch to the IEG approach would likely disincentivize staff to develop projects in FCS as their efforts would be less likely to be recognized if a country “graduates” from the FCS list while the project is being developed.

- MIGA’s definition is associated with its strategic intent to support projects in countries transitioning through to graduation from FCS status when conditions are still fragile and considerable political, and economic uncertainties remain. Additional investment, both from domestic and foreign sources, after graduation from the harmonized list is critical to ensure that there is not a reversal toward fragility.

MIGA is not consulted on whether countries should graduate from the harmonized list nor does the Agency have any specific advance knowledge of when countries will exit the harmonized list in any given year. We believe that if we were to use the harmonized list strictly on an annual basis as IEG is recommending for our strategic assessment of our work in FCS, it would discourage IFC and MIGA staff from business development activities and project preparation across all FCS countries. Many flagship projects in FCS were designed and prepared when the countries were on the harmonized list but were not on the list when MIGA’s contract of guarantee was signed. Staff working for many years on a project would not be recognized for their FCS work if the country moves out from the harmonized FCS list before the guarantee contract is closed. For example, for the Upper Trishuli-1 Hydropower Project in Nepal the team worked on the project starting in 2014 when the country was on the harmonized FCS list, but the project was approved in FY19 after the country graduated from the harmonized list.

Using the strategy-based FCS definition for private sector operations reflects the challenges of doing business in FCS, our intention of making meaningful contributions to the lives and livelihoods of the people in FCS, and the establishment of appropriate incentives for management and staff to invest their time and resources on projects in FCS.

Indeed, IEG itself adjusts the classification of FCS for portfolio analytical purposes. For example, the Results and Performance of the World Bank Group report uses project performance for FCS based on FCS classification at the time of evaluation across the Bank Group – the reason IEG does so is to capture the fragility impact in projects over the implementation period. It is also interesting that IEG’s first recommendation is to adapt existing frameworks for upscaling our FCS work, but IEG does not recommend that IFC or MIGA use a definition of FCS that supports our business in these countries. Moreover, there is no lack of transparency in MIGA’s strategy-based definition: it is clearly explained in the SBO setting out our scorecard metrics. IFC’s and MIGA’s reporting is transparently based on our strategic undertaking to address FCS countries’ challenges.

We believe it is useful to show the MIGA FCS portfolio summary if IEG’s analysis were performed based on the IFC and MIGA definition. The chart below shows the recent growth trend of FCS projects by number (in FY20) and reveals the interesting growth of smaller projects (in FY21).

Table MR.1. MIGA Guarantee Shares in FCS, comparing IEG and MIGA IFC Strategic-based Approaches for Fiscal Years 2010–21 (percent)

|

Share of FCS |

FCS According to IEG Definition |

FCS According to Strategy-Based Definition |

|

By commitment amount |

8.6 |

9.7 |

|

By number of projects |

17.1 |

19.8 |

Source: Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency.

Note: IEG = Independent Evaluation Group; IFC = International Finance Corporation; FCS = fragile and conflict-affected situations; FY = fiscal year; MIGA = Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency.

Figure MR.3. MIGA Guarantee Volume and Number of Projects, Comparing IEG and MIGA and IFC Strategic-Based Approaches by Fiscal Year

Source: Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency.

Note: IEG = Independent Evaluation Group; IFC = International Finance Corporation; FY = fiscal year; MIGA = Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency.

By taking the annual harmonized FCS list for evaluation purposes of this report, MIGA believes that an opportunity was missed to focus on the role of MIGA operations in countries that had recently transitioned from the harmonized list but remained on the IFC MIGA strategy-based FCS definition. An analysis of these engagements may have brought valuable lessons and insights for business development and possible contribution of projects to stabilization in the post-fragile context of these countries, especially in light of stakeholders’ concerns that countries may fall back into FCS status after a few years of stability after exiting from the FCS harmonized list.

- International Finance Corporation strategies have had a focus on fragile and conflict-affected situations (FCS) countries since at least 2009, adopting a special FCS strategy in 2012, while the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) has identified conflict-affected countries as a strategic priority since 2005.

- MIGA’s target for fiscal years 2021–23 (FY21–23) combines FCS countries and those that are IDA17 (17th Replenishment of International Development Association) eligible.

- For the list of FCS countries, see appendix D and https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/fragilityconflictviolence/brief/harmonized-list-of-fragile-situations.