The International Development Association's Sustainable Development Finance Policy

Chapter 4 | Insights from Sustainable Development Finance Policy Implementation in FY21

Sustainable Development Finance Policy Performance and Policy Action Portfolio

Implementation of PPAs under the DSEP is a central aspect of the SDFP’s theory of change. PPAs are determined through direct discussions with country authorities and World Bank country economists and country directors; MTI Global provides advice, knowledge, and support to ensure PPAs are realistic. To a significant extent, it is through the articulation and implementation of PPAs that address the drivers of country-specific debt vulnerabilities that IDA-eligible countries would be expected to move toward more transparent, sustainable financing, which is SDFP’s main objective.1 Of the 74 IDA-eligible countries, 55 countries were required to prepare PPAs under the DSEP (see appendix C for a list of countries). These countries were required to implement 130 PPAs in FY21. Of the 55 countries required to implement PPAs, 26 were at high risk of debt distress, 5 were in debt distress, and another 19 countries were at moderate risk of debt distress. The remaining 5 countries were MAC DSA countries, for which there were breaches of vulnerability thresholds for debt, gross financing needs, or debt profile indicators.

The SDFP secretariat classifies PPAs into three categories: debt management, debt transparency, and fiscal sustainability. The classification is not entirely informative because the categories overlap partially. For example, good debt management practices require transparency about borrowing decisions; similarly, fiscal sustainability is difficult to assess without clarity on debt stocks, borrowing, and debt service. Because of this conceptual overlap, similar PPAs are occasionally categorized differently, and there have been revisions to some PPAs’ classifications. For example, nonconcessional borrowing ceilings were originally classified under “fiscal sustainability” but have since been recategorized as “debt management” (table 4.1).2 The fiscal sustainability classification was broadly conceptualized to cover all aspects related to debt sustainability, including domestic resource mobilization.3

PPAs for most countries were spread across all three categories. PPAs were concentrated in a single category in just 4 of 55 countries (the Marshall Islands, Samoa, Tonga, and Vanuatu), and only for countries implementing only two PPAs.

More than half of the debt management PPAs (almost one-quarter of all FY21 PPAs) called for the adoption of a single-year ceiling on nonconcessional external borrowing. All IDA-only countries in debt distress or at high risk of debt distress (20) agreed to a PPA for the adoption of such a ceiling. Among blend and gap countries, about half (6 of 11) in debt distress or at high risk of debt distress agreed to PPAs requiring adoption of a nonconcessional borrowing ceiling. Among countries at moderate risk of debt distress, 4 IDA-only countries (out of 11) and 1 blend or gap country (out of 3) implemented nonconcessional borrowing ceilings.

The majority of PPAs categorized as fiscal sustainability focused mostly on fiscal transparency rather than fiscal policy. For example, audit reports on the use of COVID-19 funds (though potentially an important step toward fiscal sustainability) enhance transparency; they do not change fiscal parameters. Few PPAs have had a direct impact on spending or revenue, but there are a few examples of such measures, including an excise tax proclamation in Ethiopia and a decree to eliminate payment of ghost workers in Lesotho. The timing of the SDFP rollout with the extraordinary circumstances of COVID-19 made the implementation of fiscal policy–oriented PPAs related to fiscal consolidation (that is, procyclical fiscal policy) more difficult. At the same time, not all fiscal reforms are procyclical, and the circumstances of COVID-19 have heightened the urgency of prioritizing public expenditure and investment management and domestic revenue mobilization.

Table 4.1. SDFP Categorization of Performance and Policy Action under Debt Sustainability Enhancement Program, FY21

|

Countries |

Countries (no.) |

Agreed-on PPAs (no.) |

Distribution of PPAs (%) |

||

|

Debt management |

Debt transparency |

Fiscal sustainability |

|||

|

All DSEP |

55 |

130 |

39 |

32 |

29 |

|

FCV |

18 |

40 |

40 |

35 |

25 |

|

Small state |

14 |

29 |

41 |

28 |

31 |

|

Lending category |

|||||

|

IDA-only |

34 |

81 |

47 |

27 |

26 |

|

Blend-gap |

21 |

49 |

27 |

39 |

35 |

|

Risk of debt distress |

|||||

|

Moderate risk of debt distress |

19 |

46 |

33 |

37 |

30 |

|

High risk of debt distress |

26 |

59 |

42 |

27 |

31 |

|

In debt distress |

5 |

13 |

46 |

31 |

23 |

|

MAC DSA countries |

5 |

12 |

42 |

33 |

25 |

|

IMF program |

30 |

72 |

40 |

28 |

32 |

|

No IMF program |

25 |

58 |

38 |

36 |

26 |

Source: World Bank 2021d.

Note: DSEP = Debt Sustainability Enhancement Program; FCV = fragility, conflict, and violence; FY = fiscal year; IDA = International Development Association; IMF = International Monetary Fund; MAC DSA = Debt Sustainability Analysis for Market Access Countries; PPA = performance and policy action; SDFP = Sustainable Development Finance Policy.

Few PPAs were devoted to PIM. Although the suboptimal use of past borrowed funds has contributed to debt stress in many IDA-eligible countries,4 only 4 of 130 PPAs were targeted to improving PIM.5 This falls short of the Board-endorsed recommendation in the recent IEG evaluation World Bank Support for Public Financial and Debt Management in IDA-Eligible Countries calling for regular updates of key diagnostics of public financial and debt management to inform the design of budget support operations, investment projects, and country-specific PPAs under the newly adopted SDFP (for example, by considering improvements in PIM together with measures to improve debt transparency and debt management). In its report to the Board on this evaluation’s findings (World Bank 2021e, xxi), the Committee on Development Effectiveness suggested that “the implementation of the SDFP could pay greater attention to public investment management (PIM).”

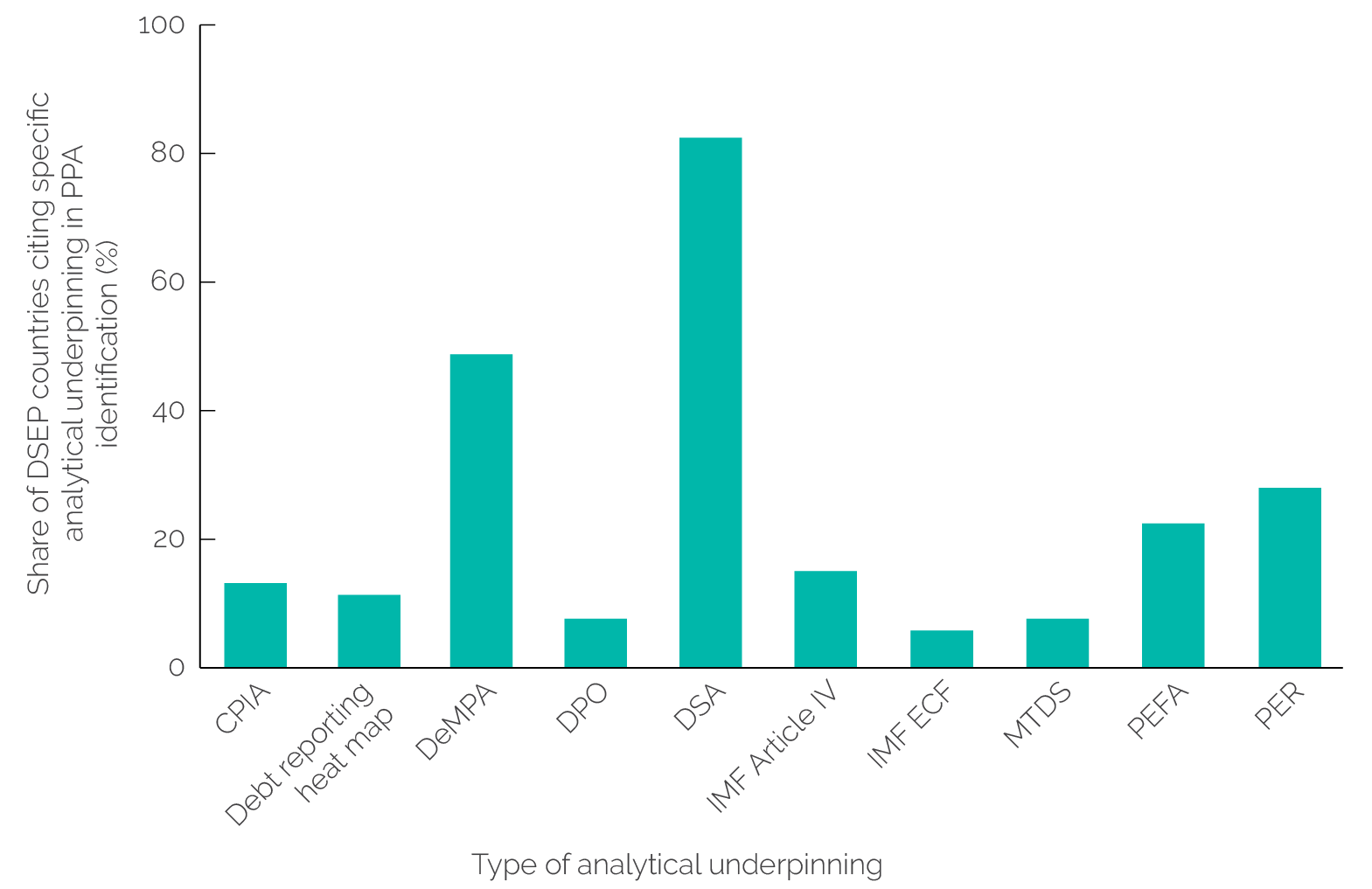

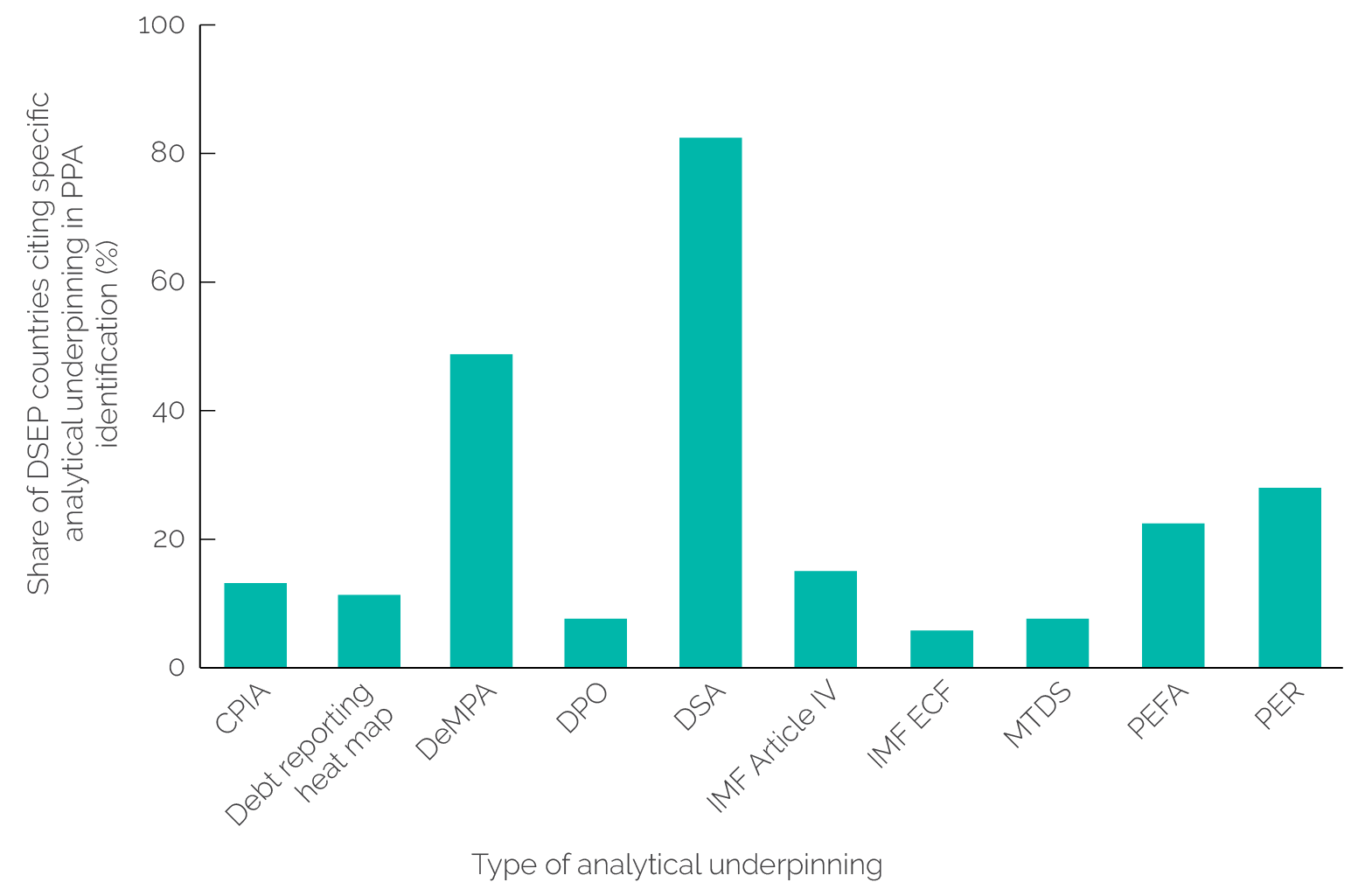

World Bank documentation on PPA recommendations and design referenced a range of analytical underpinnings. As part of the internal PPA approval process, country teams were required to indicate the main diagnostics and analysis underpinning recommendations for and design of individual PPAs (figure 4.1). A database that the SDFP secretariat maintains shows that PPA recommendations and design over FY21 drew on a range of advisory services and analytics and technical assistance, including DSAs, Debt Management Performance Assessments (DeMPAs), Public Expenditure Reviews, Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability assessments, and Country Policy and Institutional Assessments.

A key diagnostic instrument underpinning many PPAs—the DeMPA—was often either outdated or not publicly available. For the majority of countries citing the DeMPA as a key analytical underpinning, no DeMPA was publicly available, complicating assessment of the relevance of some PPAs.6 IEG’s recent evaluation, World Bank Support for Public Financial and Debt Management in IDA-Eligible Countries, noted that greater public awareness of DeMPA findings would help guide donor support and better inform public debate on country-specific reform priorities. That evaluation “acknowledged the World Bank’s active encouragement” of country authorities to publish DeMPAs and suggested that DeMPA policy shift to a “presumption” of publication, with clients needing to explicitly request nonpublication (World Bank 2021e). This evaluation likewise recognizes the World Bank’s recent efforts to actively encourage governments to publish existing DeMPAs and points to the benefits of shifting to a presumption of DeMPA publication unless governments explicitly object.

Figure 4.1. Analytical Underpinnings Cited for FY21 Agreed-on Performance and Policy Actions

Source: Independent Evaluation Group staff estimates from World Bank (2021c).

Note: CPIA = Country Policy and Institutional Assessment; DeMPA = Debt Management Performance Assessment; DPO = development policy operation; DSA = debt sustainability analysis; DSEP = Debt Sustainability Enhancement Program; ECF = Extended Credit Facility; FY = fiscal year; IMF = International Monetary Fund; MTDS = Medium-Term Debt Management Strategy; PEFA = Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability; PER = Public Expenditure Review; PPA = performance and policy action.

The process for verifying implementation of PPAs is yet to be developed fully. The SDFP FY21 Board Update lists PPAs approved over FY21, but it does not report on their implementation, the deadline for which has been extended from May 2021 to July 2021 (World Bank 2021d). The SDFP secretariat maintains a database of PPAs that does not include information on the modality and responsibility for tracking PPA implementation. In some cases, PPAs are included in DPOs either as prior actions or, on occasion, as a results indicator.7 However, although the World Bank’s legal department confirms implementation of PPAs as prior actions as part of the DPO approval process, achievement of targets for results indicators is not subject to the same standard of verification.

Limited attention has been paid to putting a framework in place to monitor PPA impact. If PPAs are implemented as prior actions in DPOs, there is a requirement for results indicators and targets with which to assess outcomes. Otherwise, PPA notes have no explicit guidance or requirement to specify indicators with which to monitor impact. The lack of a monitoring and evaluation framework significantly weakens the ability to monitor the SDFP’s overall success and to learn from implementation experience. The guidelines mention the results only once, related to the information that should be presented to the SDFP committee when implementation is under a DPO. Elsewhere, the focus is exclusively on how to identify PPAs.

About one-quarter of PPAs are prior actions in DPOs. However, this can present challenges when agreement on or approval of the DPO (that contains the PPA) is delayed or the DPO is canceled.8 Other PPAs have relied on verification outside of World Bank operations, including policy dialogue checkpoints, check-ins with country teams, and self-reporting by the country (through various mechanisms). In these cases, responsibility for confirming compliance has been unclear. The SDFP secretariat is aware of this and is working closely with teams to ensure an adequate and consistent standard of verification for all PPAs.

Insights from Country Case Studies

IEG conducted eight case studies for countries under the DSEP to learn from the SDFP implementation over FY21. The case studies were also an opportunity to evaluate the relevance of PPAs at the country level to drivers of debt stress, drawing on existing diagnostics and interviews with country teams and IMF staff. Appendix A describes the methodology for country selection and for evaluating the relevance of the PPAs of each country. Reflecting the early-stage nature of this evaluation, the assessment of relevance was undertaken in the spirit of identifying good practice and highlighting ways in which the use of PPAs could be made more impactful.

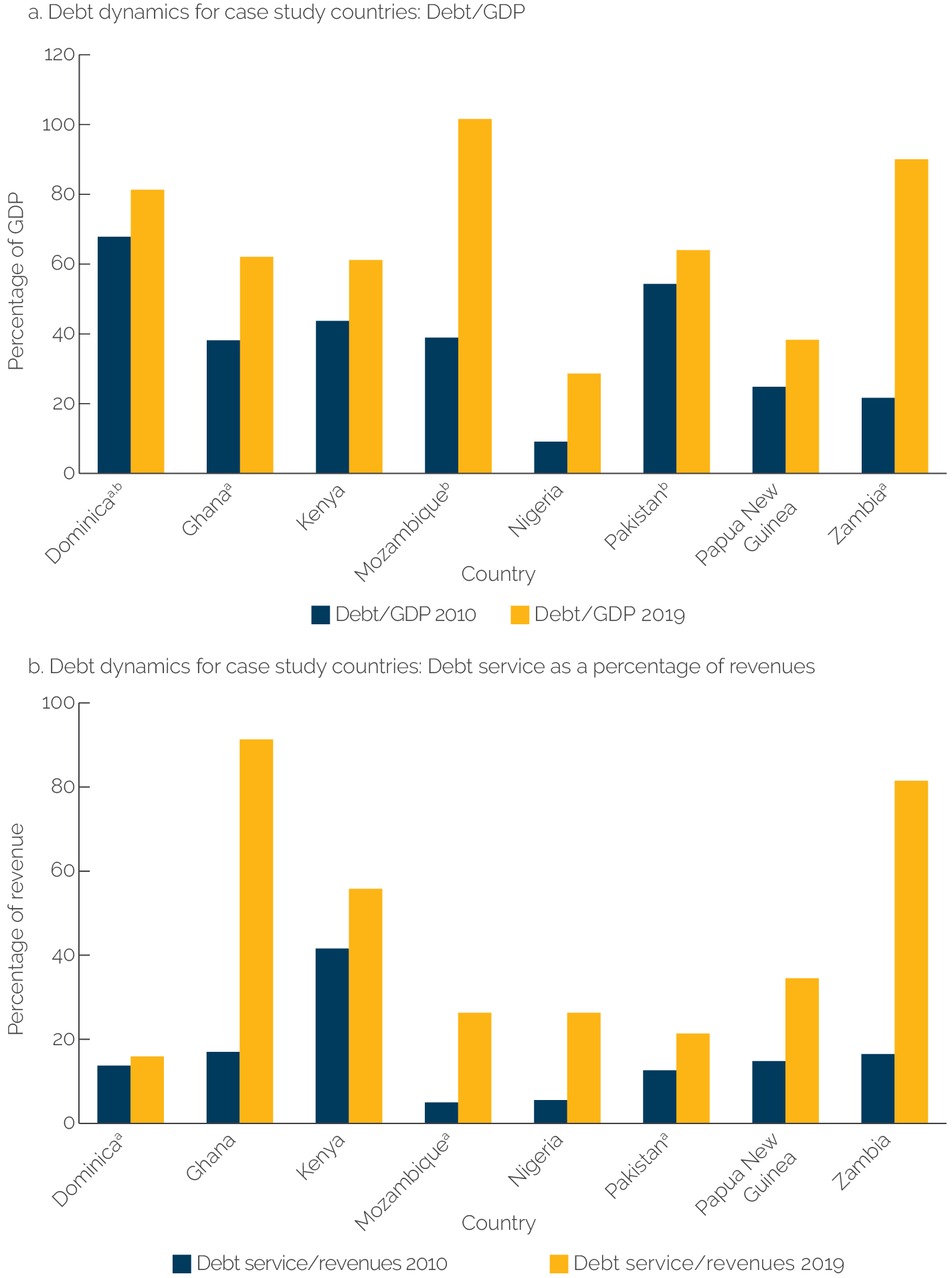

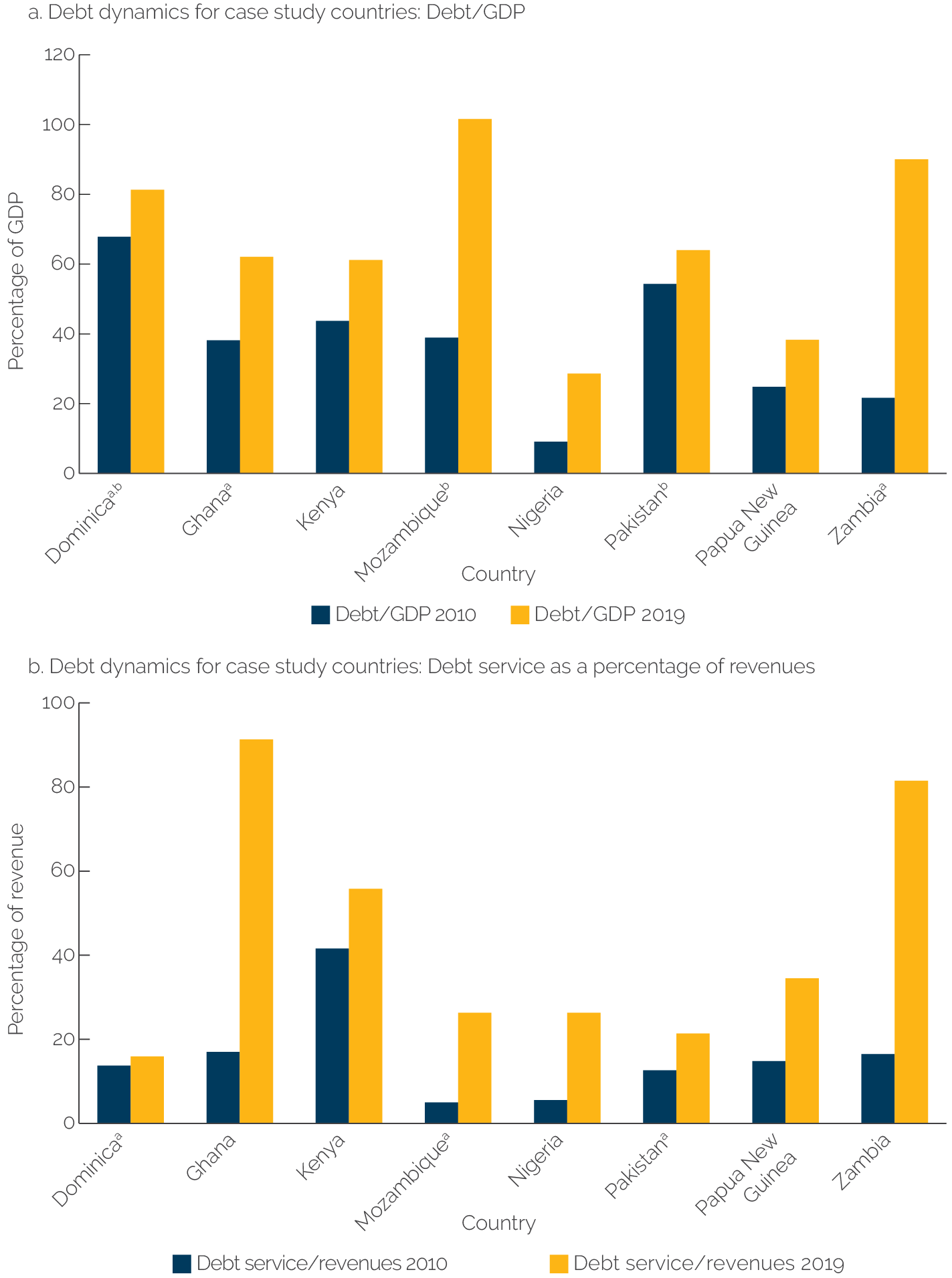

Of the eight countries selected, five were assessed to be at high risk of debt distress and one was assessed to be in debt distress. Two countries, Nigeria and Pakistan, are market access countries that breached vulnerability thresholds for debt, gross financing needs, debt profile indicators, or all three. All the countries but one (Mozambique) are IDA blend or gap. All the countries showed significant deteriorations in debt or debt service indicators between 2010 and 2019 and experienced elevations in their assessed risks, gross financing needs, or debt profile indicators (figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2. Changes in Debt and Debt Service among Case Study Countries, 2010–19

Source: Staff estimates from the International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook database.

Note: GDP = gross domestic product.Panel a: a. Central government debt. b.. 2017 figures.Panel b: a. 2017 latest available.

Drivers of rising debt distress are country specific. In Dominica, spending for natural disasters and recurrent fiscal deficits contributed to a steadily rising debt burden, pushing the country into high risk of debt distress. In Mozambique, hidden nonconcessional borrowing by SOEs led to a recategorization of debt risk, and now the country is considered in debt distress. Extremely low revenue mobilization and rising costs of debt service (partly because of expensive central bank financing of budget deficits) resulted in a fivefold rise in Nigeria’s debt service to revenue ratio. Debt service now accounts for nearly 100 percent of federal revenue (the level of government that is responsible for servicing the debt) and one-quarter of consolidated government revenue. A drop in commodity prices, an overvalued exchange rate, and realization of a large stock of contingent liabilities from SOEs all contributed to Papua New Guinea’s increase in debt-to-GDP. In Zambia, expansionary and procyclical fiscal policies and a large number of capital projects—many of which have failed to yield expected growth—resulted in debt-to-GDP almost quadrupling over the past decade.

All eight case study countries were required to implement PPAs in FY21 (see appendix D, table D.2). All but two were required to implement three PPAs each. Dominica and Papua New Guinea were the exceptions, required to implement two PPAs each (Dominica as a small state and Papua New Guinea as a country affected by fragility, conflict, and violence). Only two countries (Ghana and Kenya) implemented two PPAs in the same category (fiscal sustainability), and the rest had PPAs spread across the SDFP categories. Three countries (Mozambique, Papua New Guinea, and Zambia) had PPAs requiring nonconcessional borrowing ceilings.

IEG confirmed the implementation of 19 of the 22 agreed-on PPAs as of July 20, 2021. PPAs not implemented as of August 2021 include Dominica PPA2 (adoption of a fiscal rules and responsibility framework), Pakistan PPA2 (issuance of implementing regulations after approval of the common goods and services tax law), and Pakistan PPA3 (publication of debt bulletins and a report on COVID-19 spending). In Pakistan, both actions are pending legislative actions. The SDFP committee has formally granted a waiver to Dominica, given that the administration had made a good faith effort to pass the aforementioned fiscal rules act, which parliamentary procedure was delaying. However, the act is expected to pass within the next several months.

Relevance of Country Case Study Performance and Policy Actions

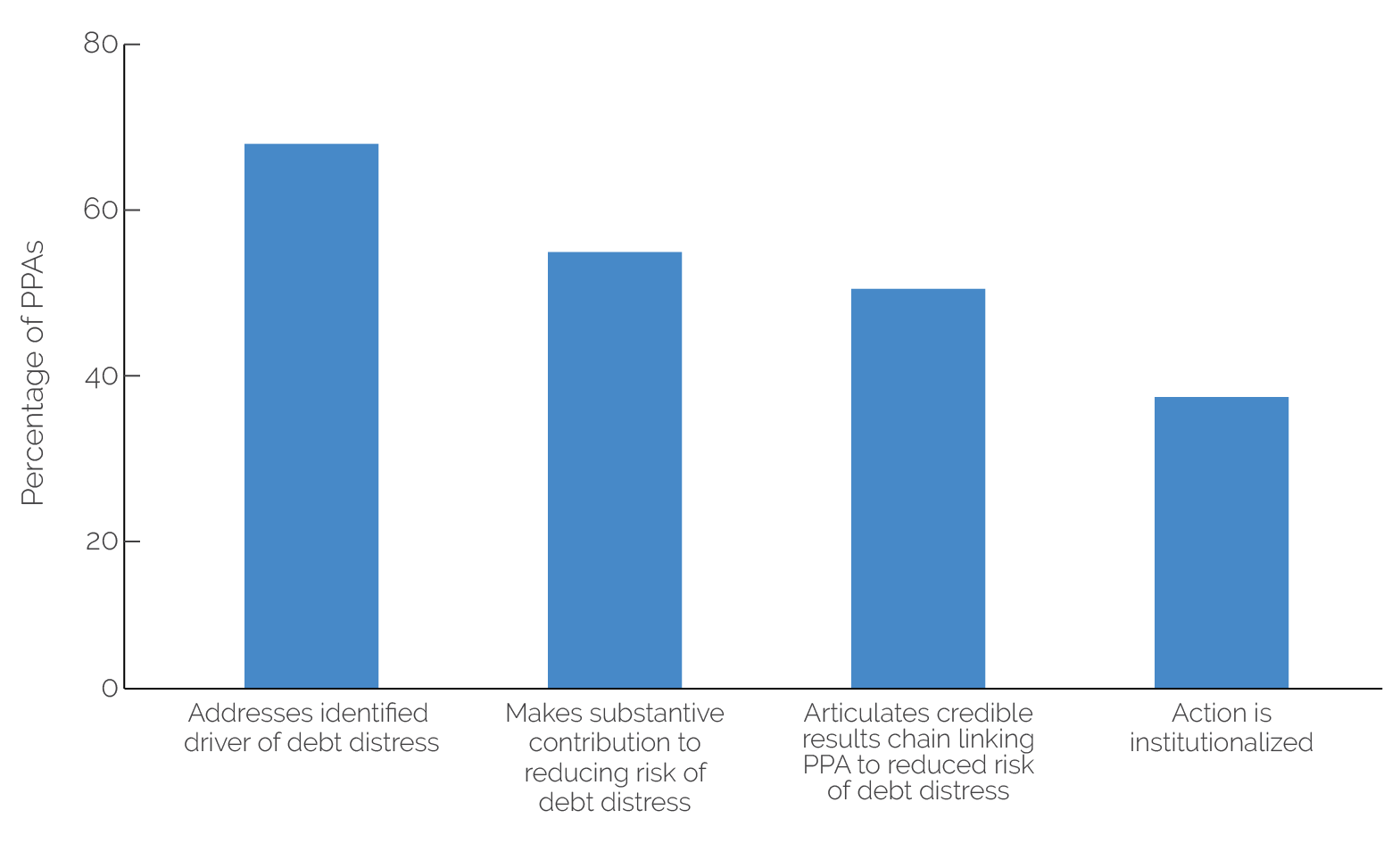

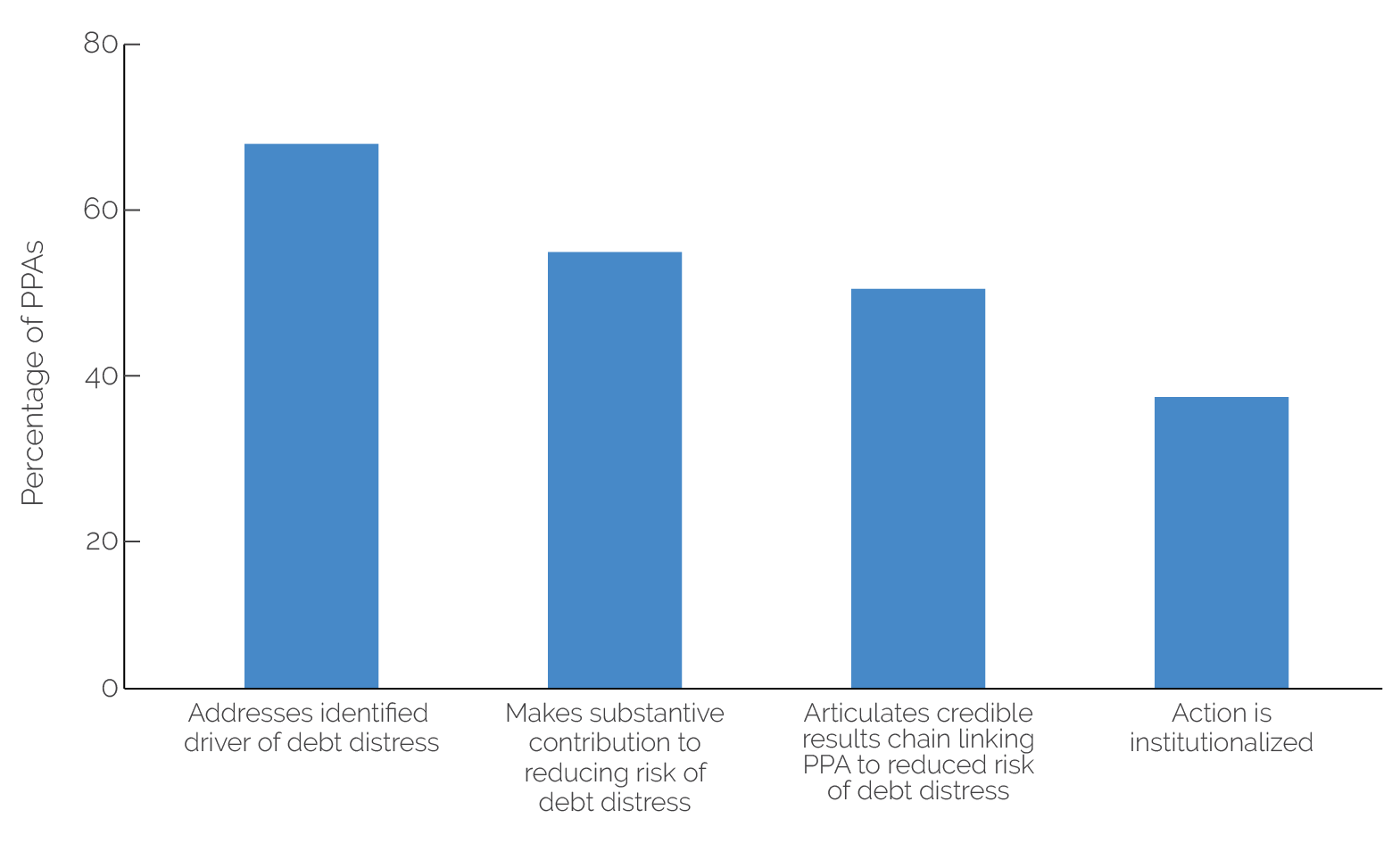

IEG evaluated PPAs for each of the case study countries for their relevance to the underlying country-specific drivers of debt stress.9 Key criteria for determining relevance included the following:

- The extent to which a PPA addressed an identified driver of country debt distress;

- The degree to which a PPA was articulated within a clear and credible results chain, linking the PPA to an eventual reduction in risk of debt distress, including through identification of other measures that may be needed to have an impact;

- The degree to which a PPA addressed a systemic weakness in an enduring manner (rather than a one-off or ad hoc manner); and

- The degree to which a PPA is expected to make a substantive contribution to reducing the risk of debt distress (see appendix D, table D.3).10

Do Case Study Countries’ Performance and Policy Actions Address Drivers of Rising Debt Stress?

Almost two-thirds of PPAs, both overall and at the country level, responded to areas of country-specific debt stress. A PPA that was well targeted to identified areas of debt risk is the cancellation of $1 billion in contracted but undisbursed debt in Zambia, which addressed (at least partly) the escalation in debt from poorly managed capital projects with questionable returns. The action was expected to have an impact on Zambia’s debt sustainability and assist in the reduction in accumulated external arrears of $5 billion. Another example is Ghana, where the amendment to the Revenue Administration Act addressed a key driver of the country’s debt stress (low domestic revenue mobilization) and is expected to expand the tax base and strengthen compliance. In Pakistan, harmonization of the sales tax addressed a recognized area of deteriorating fiscal space, and its implementation is expected to significantly reduce tax compliance costs (thereby increasing compliance). In Nigeria, the country’s amended budget, which permits access to cheaper and more transparent financing by raising domestic and external borrowing limits, was a short-term response to an immediate source of escalating debt servicing costs. In total, 14 of the 22 PPAs were well aligned to identified sources of debt stress.

Although most of the PPAs addressed identified areas contributing to debt stress, a few PPAs addressed issues that did not feature prominently in diagnostics of debt stress. For example, Nigeria’s publication of signed but undisbursed federal government loans might contribute to better debt management, but no evidence is presented to suggest that undisbursed loans are a main factor underlying the recent rise in debt stress (which is manifested in debt service). Similarly, the Kenyan National Treasury’s online publication of the latest audited statement of public debt improves the availability of timely, granular public debt data, but no evidence is presented that the lack of debt transparency was a major driver of debt stress.

Although many of the PPAs promote general good practice, major country-specific drivers of debt stress were sometimes unaddressed. For example, Zambia’s debt stress was affected heavily through borrowing to finance inefficient public investments. This would suggest the need, alongside a reduction in the stock of debt, for improvements in PIM, particularly in the selection of projects, including a requirement to undertake higher-quality ex ante appraisals of new public investment projects. According to Zambia’s 2017 Public Investment Management Assessment, public investment suffered from an estimated efficiency loss of 45 percent. Zambia’s FY21 PPAs seek to address the problem of borrowing for projects through the cancellation of undisbursed debt, focusing on projects thought to have lower expected returns. Although critical to addressing the country’s debt distress by reducing the existing debt stock, the PPAs do not tackle the shortcoming that led to the borrowing in the first place (that is, weak PIM).

Nonconcessional borrowing ceilings were included in PPAs for three case study countries, even when their absence was not a main driver of rising debt stress. For example, in Papua New Guinea, the increase in debt stress from moderate to high risk related primarily to a decline in export revenues and the government taking over the servicing of three SOE project loans as central government debt (and implicit government-guaranteed debts of SOEs and unfunded superannuation liabilities related to pensions). It is not obvious that the nonconcessional borrowing ceiling will affect the trajectory of nonconcessional borrowing in practice because the new (PPA-based) nonconcessional borrowing ceiling was set about 30 percent higher than average yearly external borrowing over the previous four years.

Most PPAs drew on current, relevant, and credible analytical underpinnings. PPAs drew on a wide body of analytical work, including DSAs, DeMPAs, Public Expenditure Reviews, and Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability assessments, along with other technical assistance analyses, Systematic Country Diagnostics, and IMF documents (particularly Article IV consultation reports). This highlights the importance of having available and up-to-date core diagnostics of a country’s public debt and financial management, institutions, and performance, which is a key recommendation of IEG’s evaluation, World Bank Support for Public Financial and Debt Management in IDA-Eligible Countries (World Bank 2021e). In the evaluation, IEG recommends that the World Bank ensure the existence and availability of such country-level diagnostics and regular monitoring of their indicators to help country teams better prioritize and sequence World Bank support, including through PPAs.

Occasionally, it was not possible to verify the links between analytical underpinnings and PPAs. The ability to evaluate the relevance of approved PPAs was constrained when underlying diagnostics were not publicly available (such as the Papua New Guinea 2020 DeMPA) or when PPAs were based on country dialogue (and no specific diagnostic document). In other cases—even when referenced analytical underpinnings were recent, credible, and available—verifiability was complicated by the fact that PPA notes did not always clearly explain why certain PPAs were chosen.

Do Case Study Countries’ Performance and Policy Actions Clearly and Credibly Articulate the Results Chain Linking the Performance and Policy Actions to Reduced Debt Stress?

Many PPAs represent single steps within a longer results chain to reduce debt stress, but subsequent actions are often needed to ensure impact. Where this is the case, PPA efficacy requires clarity on next steps. Although situating PPAs in the context of a longer-term theory of change is not required as part of the SDFP, having such clarity can signal to development partners and the public the concrete actions required to address the underlying causes of high and rising debt stress. It can also provide a clear basis from which the World Bank can draw in articulating future PPAs or prior actions in DPOs.

Half the case study PPAs are situated explicitly within the results chain required for impact (sometimes with subsequent actions identified to take reforms further along the results chain). For example, Kenya’s PPA notes clearly articulate how PPA1, on approval of PIM regulations and inventory of public investment projects, fits into the broader results chain. It explains subsequent steps necessary for impact after passage of the regulations, including support for full implementation of PIM and project monitoring and evaluation guidelines. Additionally, it explains how the inventory exercise will be used to help determine which projects could be terminated through submission to the cabinet of recommendations on how to streamline Kenya’s project portfolio. Conversely, other PPAs were presented in isolation, with little clarity on how the supported actions would be taken forward. Ghana’s three FY21 PPAs, for example, do not explain how the proposed actions will lead to longer-term outcomes, and it is necessary to refer to the Project Appraisal Document of the Ghana Economic Management Strengthening Project (from which the PPAs were derived) to find out.

Do Case Study Countries’ Performance and Policy Actions Support Lasting Solutions to Drivers of Debt Stress?

In several cases, PPAs involved changes in institutional requirements or arrangements that would have a more enduring impact. Of the 22 PPAs in the eight case studies, 13 institutionalized actions (through legal amendments, regulatory changes, or well-disseminated public commitments to particular actions). Pakistan’s PPA2, for example, requires legislation to harmonize the goods and services tax at the federal and provincial levels and publication of implementing regulations. These measures are aimed at streamlining and improving revenue collection and directly address the issue of low tax revenues, which is one of the key drivers of debt distress in Pakistan.

However, some PPAs were one-off actions, requiring repeated action to have enduring impact. For example, the expansion of coverage of Dominica’s debt reporting to parliament to include all active loan guarantees was a valuable measure, but PPA1 called for the submission of the more inclusive debt report to parliament in FY21 only. A stronger measure might have required submitting the debt report to parliament annually, which would have depoliticized the decision to report comprehensive debt information and not required subsequent decisions on publication. Although the country team has indicated the intention to have a subsequent PPA on submission of the FY22 debt report to parliament next year, this approach misses the opportunity to depoliticize publication by making it a statutory requirement. Therefore, subsequent PPAs could be used to address other drivers of debt stress.

In a few cases, institutionalization was achieved through efforts parallel to PPAs. Mozambique’s PPAs were one-off actions (that is, publication of the annual debt report, adoption of a zero nonconcessional borrowing limit on external public and publicly guaranteed debt for the current FY, and production of credit risk reports for seven SOEs using a new credit risk assessment framework). But ongoing dialogue between the World Bank country team and the client has led to ongoing compliance with the integration of debt reporting and the credit risk assessment framework into the regulations of the country’s new Public Financial Management Act. The act’s regulations now mandate the publication of annual debt reports that cover the SOE sector and fiscal risk statements that contain SOE credit risk reports. The PPAs were used as a bridge to the enactment of the Public Financial Management Act.

Do Case Study Performance and Policy Actions Make a Substantive Contribution to Reducing Debt Stress?

For more than half of the PPAs, the action is expected to make a substantive contribution to reducing debt stress. In Nigeria, for example, the average interest rate on the central bank overdraft is 3–5 percentage points higher than federal government bonds and treasury bills, and revisions to borrowing limits should yield immediate and substantial savings in debt service (a key driver of debt stress in Nigeria). Creating the borrowing headroom to allow Nigeria to borrow at lower rates is expected to yield annualized cost savings of about $500 million, or about 10 percent of total interest payments in 2019. Similarly, Ghana’s narrow tax base, low tax compliance, and overgenerous exemptions dampen domestic resource mobilization. Amending the Revenue Administration Act of 2016 to reduce tax exemptions and strengthen voluntary disclosure is expected to offset the government’s severe decline in revenue over the medium term.

Figure 4.3. Proportion of Country Case Study Performance and Policy Actions Meeting Specific Relevance Criteria

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: PPA = performance and policy action.

In some cases, however, the contribution to addressing the drivers of debt stress is expected to be modest. For example, in Zambia, PPA1 required adoption of a zero nonconcessional borrowing ceiling on contracting new external public and public guaranteed debt in 2021 (such ceilings were adopted for all countries at high risk of debt distress or already in distress). However, the additionality of this action was likely modest because the government of Zambia had already postponed the contracting of all new nonconcessional loans indefinitely: In May 2019, a cabinet decision effectively put a nonconcessional borrowing ceiling in place. This same cabinet directive also included a measure to cancel some committed but undisbursed loans to free up at least $6 billion in contracted but undisbursed loans (out of $9.7 billion of such debt), which questions the additionality of Zambia’s PPA2 on cancellation of at least $1 billion of debt by May 2021. Although it is clear that a zero ceiling would help prevent the buildup in debt, and that cancellation of undisbursed debt can reduce the debt stock, the value added of duplicating preexisting and credible commitments to zero ceilings is minimal. Figure 4.3 summarizes the findings of an analysis of the relevance of PPAs for the country case studies.

Country Teams’ Implementation Issues

Country teams’ ability to conceptualize the appropriate PPAs relies on a range of guidance mechanisms. Several country teams described the guidance they received from the SDFP secretariat (for general information on the policy); from Operations Policy and Country Services; and from the Equitable Growth, Finance, and Institutions’s debt unit (for technical guidance on PPAs) as “instrumental” for articulating relevant PPAs. These channels of support were particularly helpful because the SDFP implementation guidelines were in development and further clarification was needed.

Country teams mentioned several areas where clarity could be strengthened. One area was debt risk screening for MAC DSA countries. Although the process for screening LICs was clear, there was less clarity about how MAC DSA countries would be assessed for debt risk, who would make that decision, and when the decision would be made. In Nigeria, this lack of clarity reduced the time the country team had to identify and consult on PPAs. There was also lack of clarity on the necessity of including a nonconcessional borrowing ceiling among PPAs for countries at high risk of debt distress (particularly for blend countries). In two countries (Ghana and Zambia), staff were under the impression that a nonconcessional borrowing ceiling needed to be included among the PPAs, even though nonconcessional borrowing ceilings were already in place.

Several country teams saw a need for additional resourcing for the SDFP. These teams argued that developing PPAs and implementing them requires significant support, particularly for countries with very low capacity. In Dominica, for example, it was relatively easy to identify a PPA related to improving the debt management report (drawing on recommendations from the DeMPA), but the government needed significant support to draft the report. A PPA related to a fiscal rules framework also required significant technical assistance (which the country team resourced from a Global Tax Trust Fund). Although the Debt Management Facility is the likely source of financing for technical assistance related to some aspects of SDFP implementation, the number of countries expecting to undertake actions could imply efforts to ensure that technical assistance demand matches supply.

The limited time between internal PPA approval and the PPA implementation deadline affected some PPAs’ ambition. Short timelines sometimes made it difficult to implement more ambitious PPAs. For example, Nigeria’s PPA note was approved in February 2021 after seven revisions.

- Creditor coordination under the Program of Creditor Outreach is the other dimension to encourage sustainable borrowing.

- The Sustainable Development Finance Policy secretariat maintains a database charting policy implementation, which is updated continually. As of the end of April 2021, the implementation database categorized nonconcessional borrowing ceilings as actions toward fiscal sustainability. Nonconcessional borrowing ceilings were subsequently reclassified as debt management actions.

- In fiscal year 2021, 7 of 55 countries implementing performance and policy actions (PPAs) had domestic resource mobilization–related PPAs.

- World Bank (2021e) found that relatively few International Development Association–eligible countries that are currently at risk of or in debt distress received development policy operation support to strengthen public investment management. During the evaluation period, only 7 of 30 International Development Association–eligible countries at high risk of or in debt distress (as at 2017) had development policy operations with prior actions related to public investment management.

- Countries implementing PPAs related to public investment management include The Gambia, Grenada, Kenya, and Maldives.

- Debt Management Performance Assessments are confidential and require government approval for publication.

- For example, Fiji’s PPA2, in which the Ministry of Economy includes the risk profiles of publicly guaranteed liabilities in the government debt status report, is a results indicator on the approval of a government guarantee policy for granting guarantees to government entities (Fiji Second Fiscal Sustainability and Climate Resilience development policy operation).

- This was the case for two of Zambia’s three fiscal year 2021 PPAs.

- See appendix D for a full list of PPAs for case study countries.

- Although criterion 1 is directed to the sources of debt stress (for example, revenue or expenditure challenges), criterion 4 assesses the degree to which the PPA makes a meaningful contribution toward reducing debt stress risks. It is possible that a PPA addresses a driver of debt stress but that the contribution toward lowering the associated risk is modest.