The International Development Association's Sustainable Development Finance Policy

Chapter 1 | Introduction

This report is an early-stage evaluation of the International Development Association (IDA) Sustainable Development Finance Policy (SDFP). The Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) prepared the report at the request of the Committee for Development Effectiveness of the World Bank Group’s Board of Executive Directors to provide timely input to strengthen the SDFP’s effectiveness. The urgency of ensuring an effective SDFP rollout is heightened by the compounding effect on debt stress that many IDA-eligible countries face because of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic’s economic impact. Its findings will also help inform discussions in the context of the 20th Replenishment of IDA.

The evaluation provides an assessment of the SDFP’s design, early rollout, and initial country-level application, with the aim of identifying opportunities to strengthen the policy and its implementation. Given its early stage, process and guidance are often being devised in real time, and World Bank staff and management are learning from experience. Staff and management have already acknowledged many of the shortcomings in design and implementation raised in this evaluation and are in the process of addressing them. This evaluation recognizes these efforts where possible.

The World Bank conceived the SDFP in response to a rapid increase in debt levels and debt stress over the past decade in many IDA-eligible countries. The financing needs of IDA-eligible countries are substantial because they seek to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, and borrowing has been an important source of financing. Public sector borrowing can enable countries to finance investments that are essential for economic growth and poverty alleviation and can enable fiscal policy to play a countercyclical role during economic downturns. However, when debt levels become unsustainable, debt service on public sector borrowing can crowd out critical development spending, choke off access to affordable finance, and derail the development agenda.

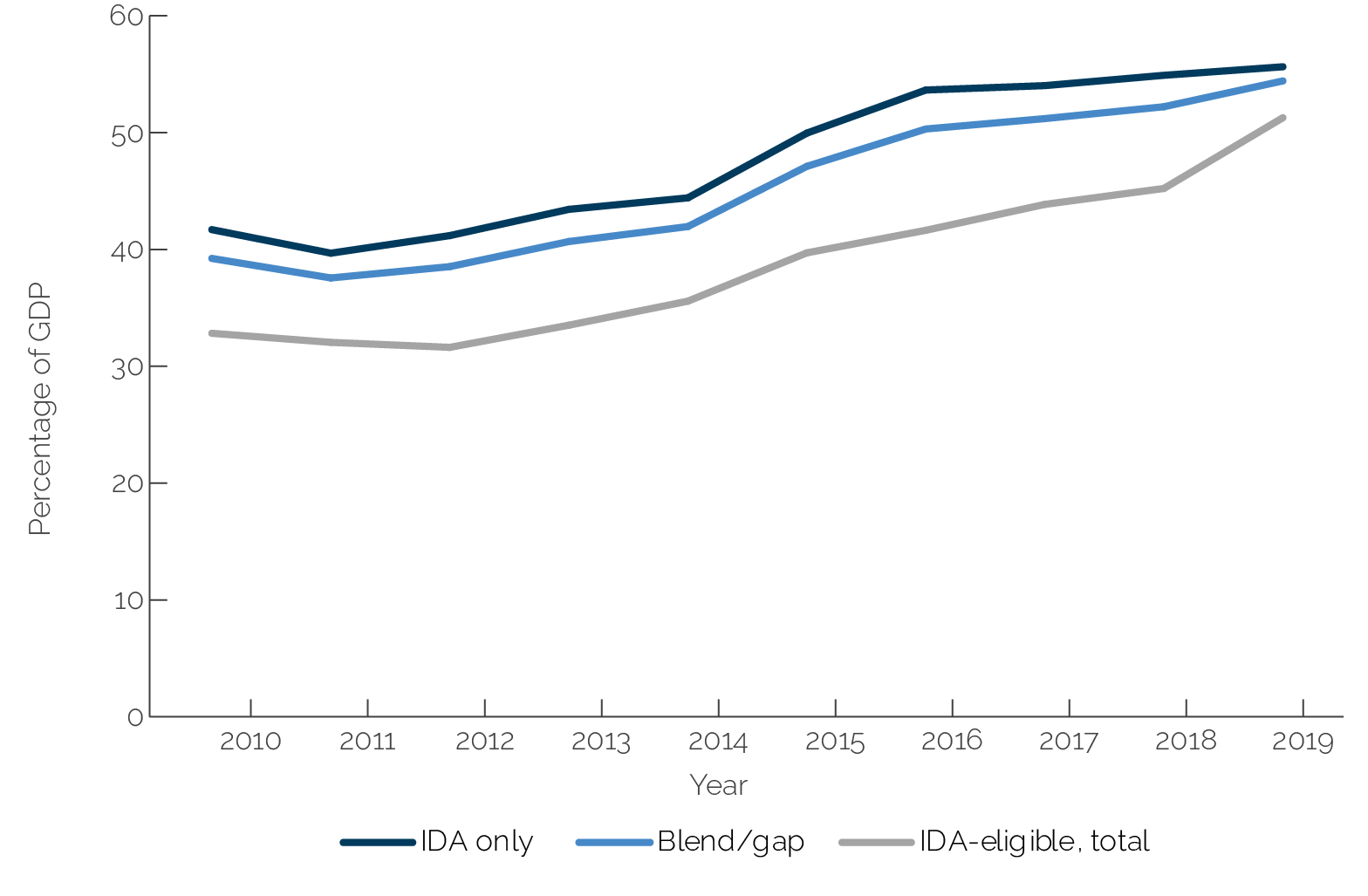

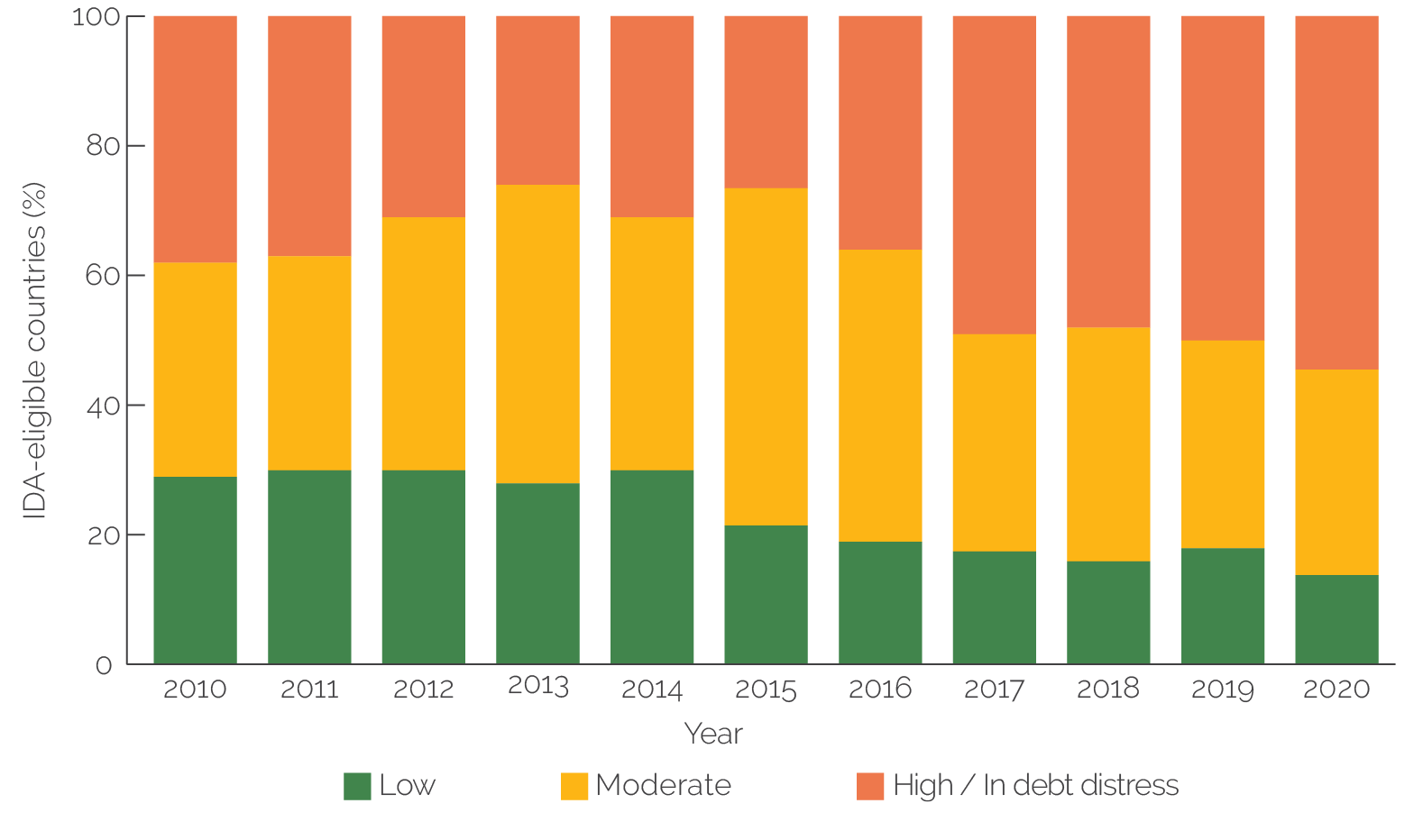

An upsurge in borrowing took place across countries at every level of development in the wake of the global financial crisis and in the context of historically low global interest rates. The resulting increase in debt was particularly burdensome for lower-income countries, many of which had low domestic revenue mobilization and weak public investment management (PIM). Between 2012 and 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, general government gross debt in IDA-eligible countries had climbed from 38 to 54 percent of gross domestic product (GDP; figure 1.1),1, 2 and the number of IDA-eligible countries at high risk of or in debt distress more than doubled from 19 to 40. More than half of IDA-eligible countries experienced an increase in their assessed risk of debt distress over the period, with the majority falling into high risk of debt distress (figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1. Public Debt as a Share of GDP in International Development Association-Eligible Countries, 2010–19

Source: World Development Indicators database (July 2021).

Note: GDP = gross domestic product.

Figure 1.2. Evolution of Debt Distress Ratings in International Development Association–Eligible Countries, 2010–20

Source: World Bank 2020b; International Monetary Fund Debt Sustainability Analysis (database), International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC (accessed April 2021), https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/debt-toolkit/dsa.

Note: These are the latest estimates (depending on the date of the debt sustainability analysis update). IDA = International Development Association.

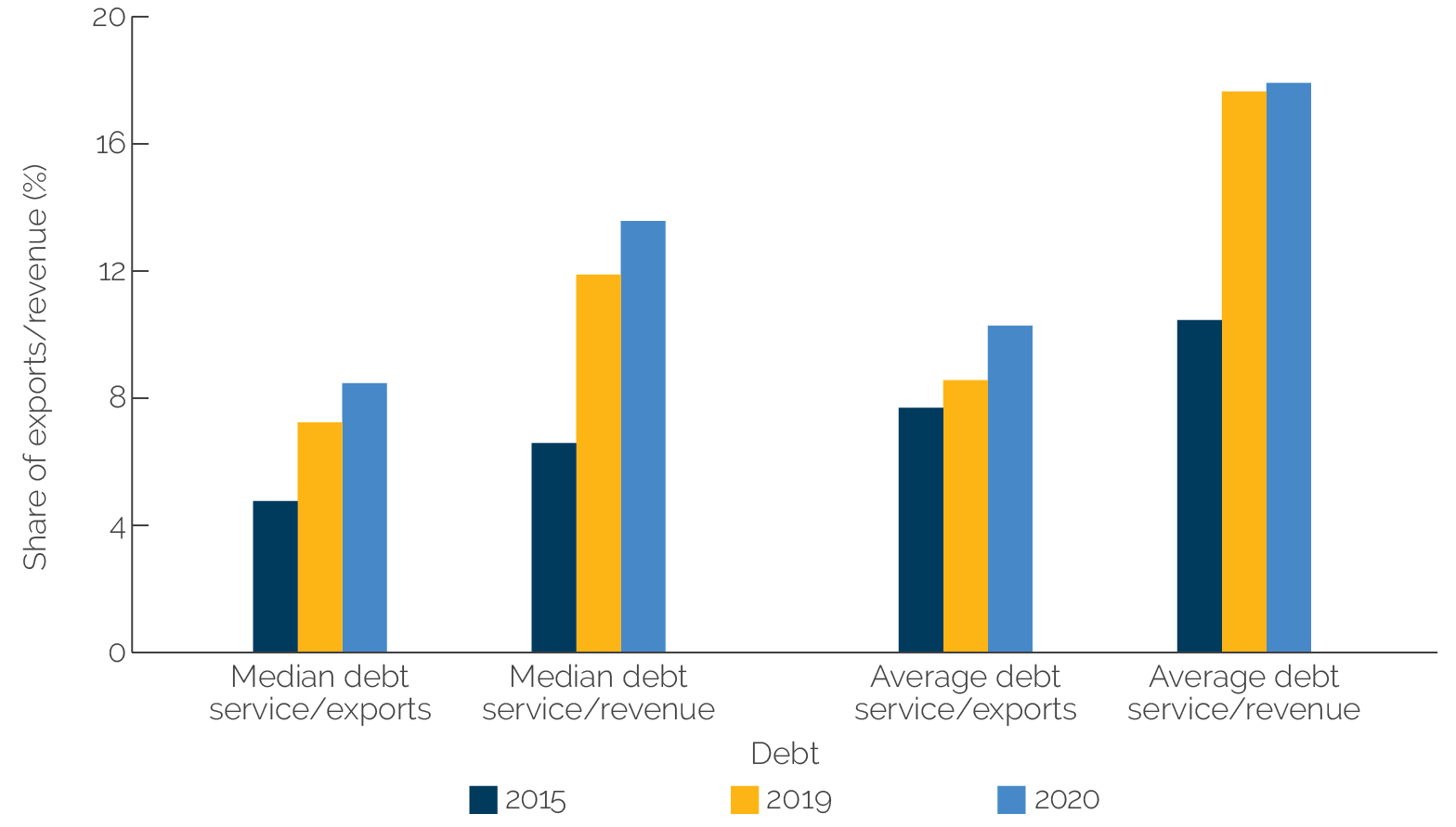

The rise in public debt has been accompanied by a rise in public debt service as a share of revenues. This increase in debt service has crowded out spending on core public services such as education, health, and basic infrastructure. Consolidated government debt service exceeded 25 percent of revenue and grants in 40 percent of IDA-eligible countries for which data were available in 2020.3 Median public debt service payments as a share of revenue doubled from 6.7 to 13.7 percent (figure 1.3). High and rising indebtedness, often on shorter maturities, has also exposed already vulnerable countries to rollover, exchange rate, and interest rate risks that have increased fiscal, external, and financial sector vulnerabilities.

Figure 1.3. Public Debt Service Burdens in International Development Association–Eligible Countries, 2015–20

Source: Staff estimates from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund Debt Sustainability Analysis (database).

Note: IDA = International Development Association.

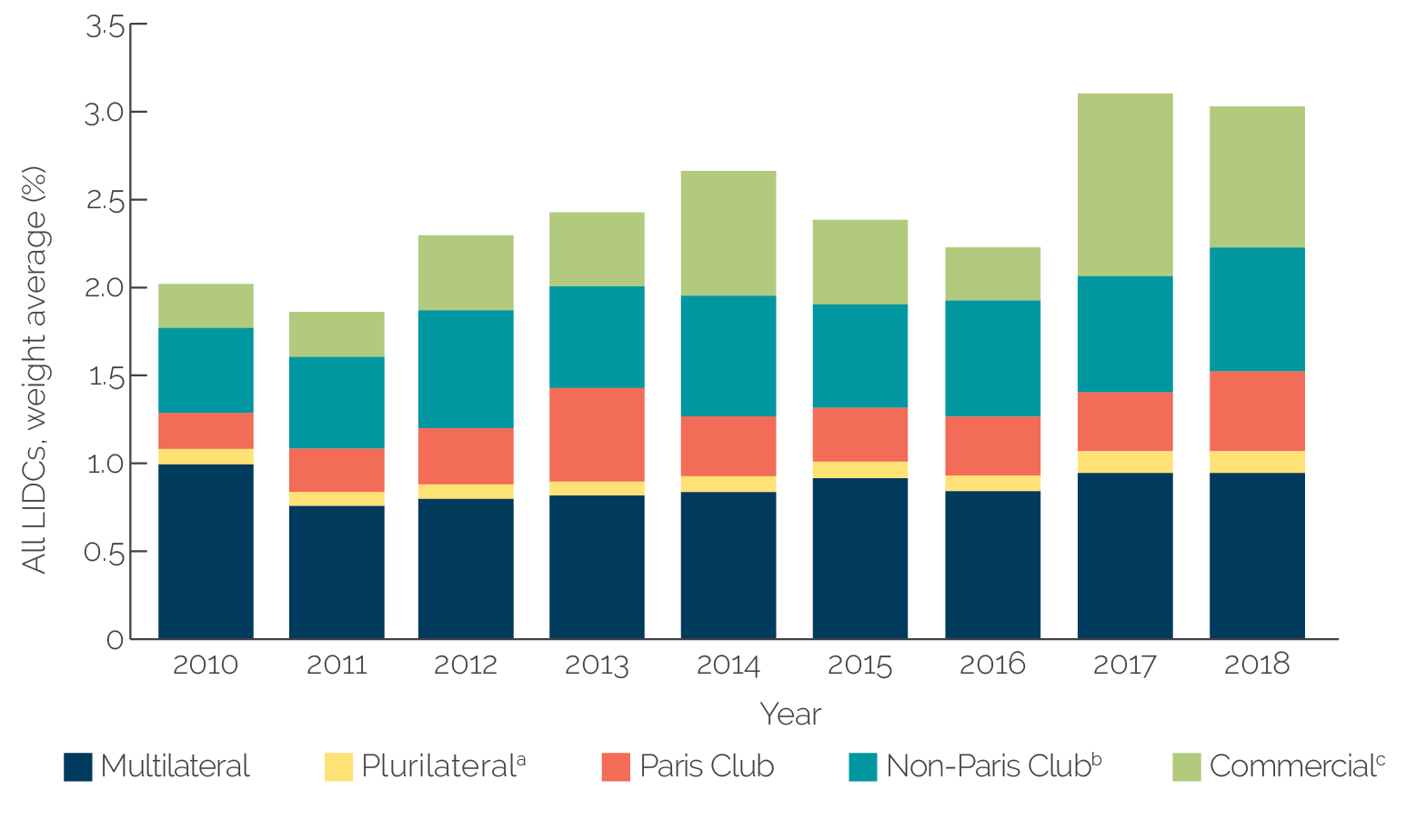

The increased availability of financing, particularly from commercial and non–Paris Club bilateral creditors, contributed to the buildup of debt. In 2010, multilateral institutions accounted for about half of lending to low-income countries (LICs). Within a decade, that share had declined to less than one-third as commercial and bilateral creditors grew to dominate lending flows (figure 1.4). Bilateral credit has also shifted from traditional creditors to nontraditional lenders, most importantly China.4 There has also been a pronounced increase in commercial financing (for example, Eurobonds and commercial bank lending), with its share in total lending to IDA-eligible countries more than doubling over the past decade and now accounting for more than one-quarter of disbursed and outstanding external debt.5

Figure 1.4. Disbursed Lending to Low-Income Economies by Creditor Type, 2010–18

Source: World Bank and IMF 2020.

Note: Calculated as the sum of disbursements divided by gross domestic product. This highlights the supply of credit to low-income developing countries. LIDC = low-income developing countries. a. See appendix III of IMF 2018. b. Includes disbursements from China. c. Includes disbursements from bonds and other instruments.

Purpose and Scope of the Early-Stage Evaluation

In the context of rising debt, debt service, and debt distress, the SDFP was conceived during the 19th Replenishment of IDA (IDA19) to support IDA-eligible countries in their efforts to achieve and maintain debt sustainability. Noting that “rising debt vulnerabilities in IDA-eligible countries could jeopardize their development goals,” IDA19 deputies asked for options from the World Bank to expand and adapt IDA’s allocation and financial policies to support financial sustainability and help IDA achieve country development goals while minimizing risks of debt distress (World Bank 2019a). The SDFP became effective on July 1, 2020, and replaced the Non-Concessional Borrowing Policy (NCBP), which had sought to support debt policies and long-term external debt sustainability in IDA-eligible nongap countries by focusing on external, nonconcessional financing flows.

The SDFP’s objective is to incentivize IDA-eligible countries to borrow sustainably and to promote coordination among IDA and other creditors. It consists of two pillars: the Debt Sustainability Enhancement Program (DSEP) and the Program of Creditor Outreach (PCO). The DSEP encourages country-level actions to enhance debt transparency, promote fiscal sustainability, and strengthen debt management by requiring countries at moderate and elevated risk of debt distress to adopt concrete performance and policy actions (PPAs) to address the drivers of their country-specific debt vulnerabilities. The PCO aims to use the World Bank’s potential as a convener to promote information sharing, dialogue, and collective action among creditors of IDA-eligible countries, including traditional and nontraditional creditors.

This evaluation examines the SDFP’s design and early implementation, while acknowledging the difficult context (owing to the COVID-19 pandemic) in which the policy was introduced. The design was assessed regarding its relevance to the drivers of debt stress in IDA-eligible countries over the past decade and lessons learned from experiences in dealing with threats to debt sustainability in LICs. Reflecting its early-stage nature, the evaluation examines the SDFP implementation during its first year (fiscal year [FY]21). In addition to reviewing the use of PPAs across all DSEP countries, the evaluation conducted case studies for eight countries to assess the agreed-on PPAs’ relevance in relation to country-specific debt challenges and to the SDFP’s objectives.6

Given the evaluation’s early-stage nature, outcomes of the SDFP as a whole or of individual PPAs are not assessed because clear impacts on debt sustainability and debt stress will take time to materialize. Additionally, the IEG team did not consider it possible to evaluate the impact of SDFP-related set-asides of IDA allocations on country incentives because set-asides would take effect only in the second year of SDFP implementation (although there are questions about the set-aside framework’s design that can be posed legitimately at this early stage). Similarly, because the objectives, form, and function of the PCO are not yet elaborated fully, assessment of the PCO is limited. But previous experience with creditor coordination, including in the context of the NCBP, points to a need to clarify the program’s mandate and ambition. Appendix A provides more details on the scope and methodology used in this evaluation and how the team addressed the questions posed in the evaluation’s Approach Paper (World Bank 2021b).

This report is structured as follows: Section 2 discusses the drivers of the increase in debt stress in IDA-eligible countries over the past decade. Section 3 assesses the extent to which the SDFP, as designed, responds to the debt sustainability challenges faced by IDA-eligible countries and lessons learned from past efforts at managing debt stress. Section 4 presents an assessment of PPA relevance and design based on a review of all PPAs and eight country case studies, and section 5 presents conclusions and recommendations.