The World Bank Group in Ukraine, 2012–20

Chapter 2 | Governance and Anticorruption

Highlights

Governance and anticorruption gained importance in World Bank support to the government’s reform agenda after 2014 and received another boost after the change in administration in 2019.

The World Bank made important contributions to advance governance and anticorruption reforms, including through help in establishing new apex anticorruption institutions. It effectively used opportunities to advance the governance and anticorruption agenda within sectoral reform programs, including public financial management, energy, health, and social protection. The World Bank also supported a successful communications campaign to build public support for several aspects of the reform agenda.

A lack of attention to the justice sector and minimal progress on public administration reform continue to undermine the impact of broader reforms. Anticorruption institutions have obtained few convictions for corruption-related offences, changes to bankruptcy regimes have not made a meaningful dent in the high levels of nonperforming loans, and public perception of the level of corruption has not improved significantly.

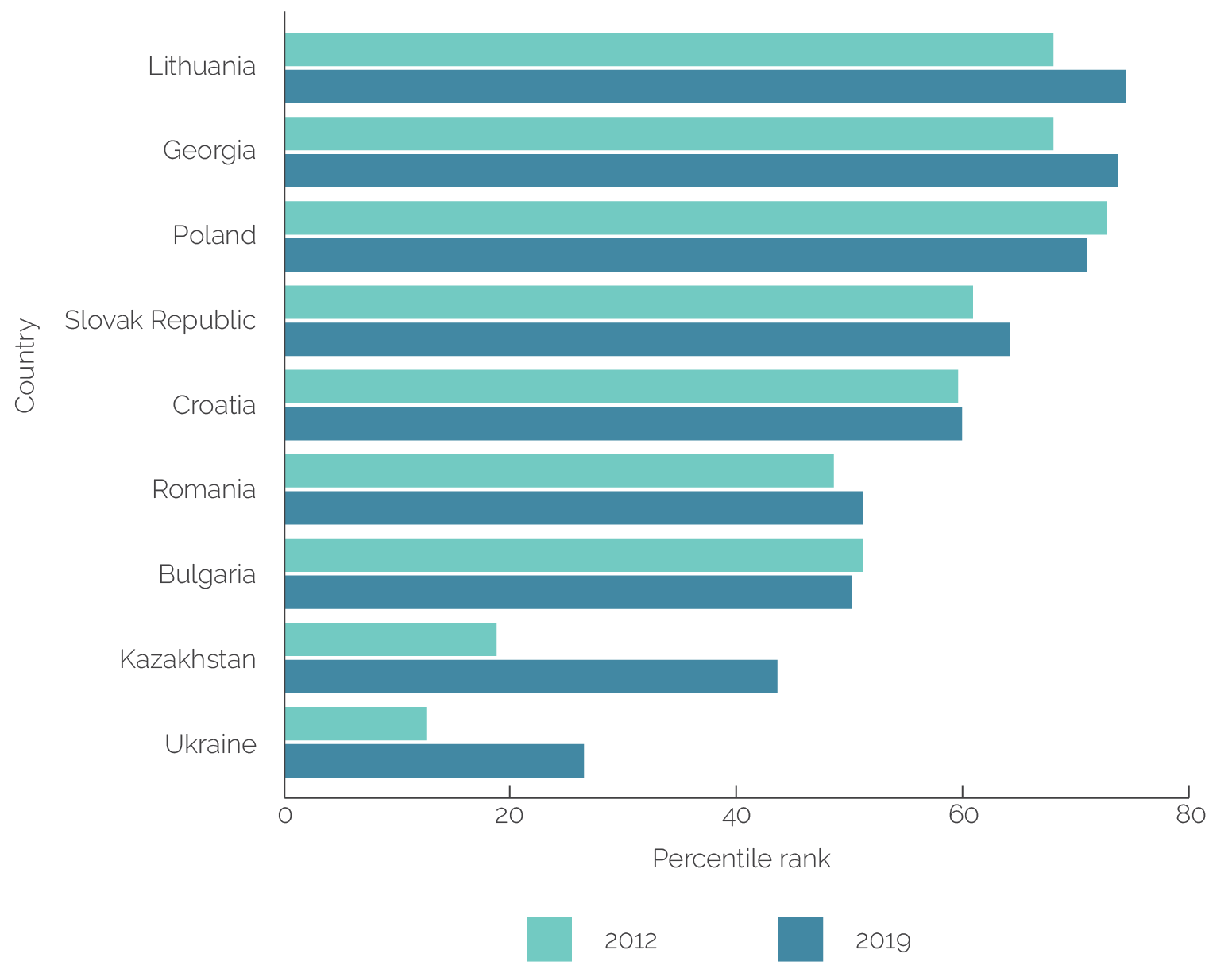

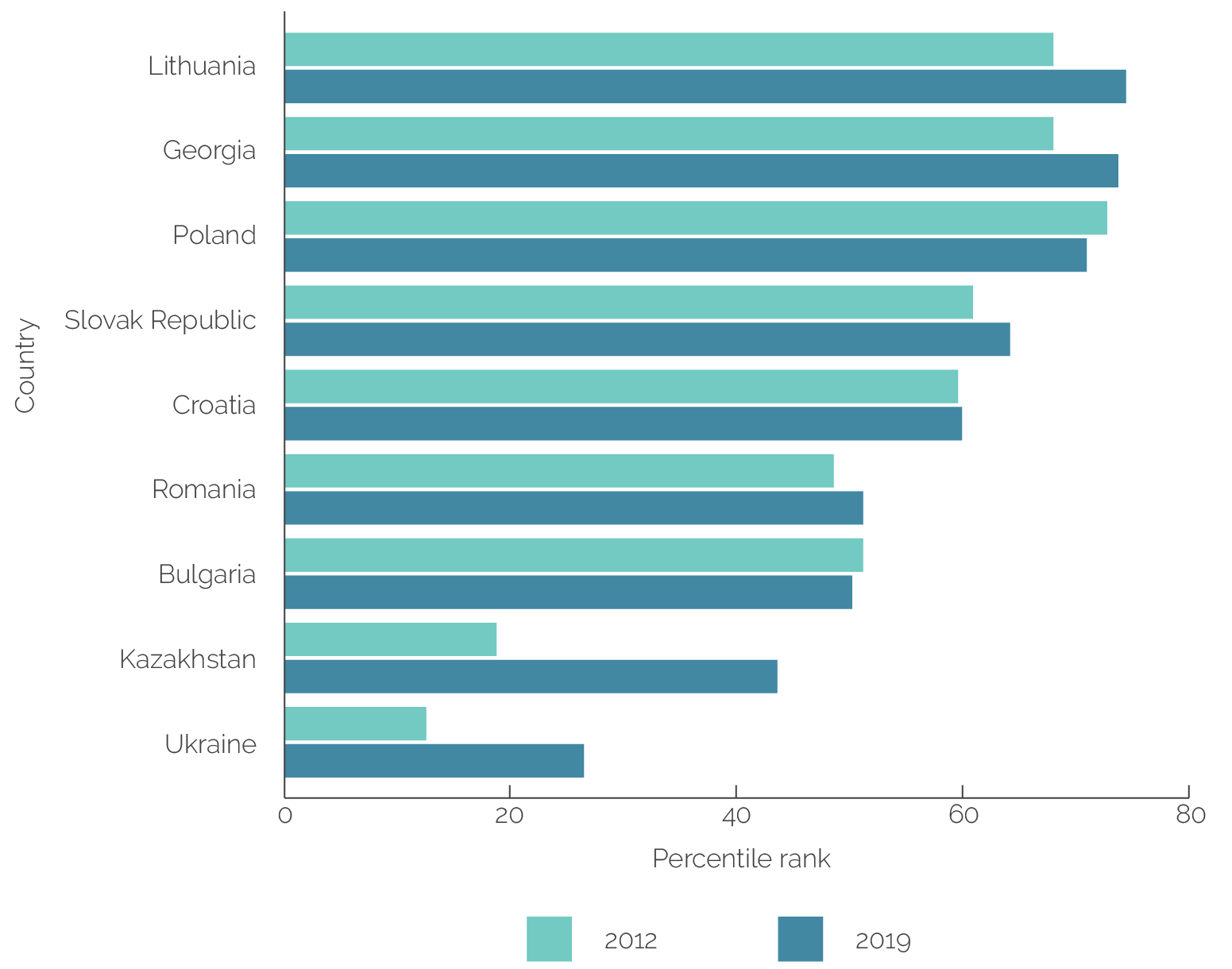

Ukraine’s governance shortcomings have been well-documented (table 2.1). The country has been continually ranked well below its Eastern European neighbors on most international corruption indexes (figure 2.1), reflecting the fact that corruption and state capture have been deeply entrenched. Lack of political commitment to reform and opposition from vested interests delayed policy reforms until 2014, when anticorruption gained importance in the government’s policy agenda in response to pressure from civil society and international partners. Reform momentum received a boost after the change in administration in 2019.

Table 2.1. Ukraine: Select Governance Indicators, 2010–19

|

Indicators |

2010 |

2014 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

Corruption Perceptions Index score (TI)a |

— |

26 |

30 |

32 |

30 |

33 |

|

Open Budget Index score (IBP)b |

62 |

46 |

54 |

— |

63 |

— |

|

Control of corruption (WGI)c |

–1.03 |

–0.99 |

–0.78 |

–0.87 |

–0.71 |

— |

|

Government effectiveness (WGI) |

–0.78 |

–0.41 |

–0.46 |

–0.42 |

–0.30 |

— |

|

Regulatory quality (WGI) |

–0.52 |

–0.63 |

–0.32 |

–0.22 |

–0.26 |

— |

|

Rule of law (WGI) |

–0.81 |

–0.79 |

–0.71 |

–0.72 |

–0.70 |

— |

|

Voice and accountability (WGI) |

–0.08 |

–0.14 |

0.01 |

–0.01 |

0.06 |

— |

|

Political stability and absence of violence (WGI) |

0.01 |

–2.02 |

–1.87 |

–1.83 |

–1.52 |

— |

Sources: International Budget Partnership; Transparency International; World Bank Worldwide Governance Indicators database.

Note: Corruption Perceptions Index scores are not comparable between 2010 and 2012–20; data for IBP are available for 2010, 2015, 2017, and 2019. IBP = International Budget Partnership; TI = Transparency International; WGI = Worldwide Governance Indicators; — = not available.a. Corruption Perceptions Index scores relate to the degree to which corruption is perceived to exist among public officials and politicians by businesspeople and country analysts. Scores range between 0 (highly corrupt) and 100 (highly clean). See www.transparency.org. b. Open Budget Index scores are a measure of budget transparency. The index uses individual indicators that assess whether the central country government makes key budget documents available to the public in a timely manner and whether the data contained in these documents are comprehensive and useful. Score ranges between 0 (highly nontransparent) and 100 (highly transparent). See the International Budget Partnership Open Budget Survey rankings, https://internationalbudget.org/open-budget-survey/rankings.c. The WGI relate to the strength of governance performance along six dimensions. Scores range from –2.5 (weak performance) to 2.5 (strong performance). The WGI are a research data set summarizing the views of the quality of governance provided by a large number of enterprise, citizen, and expert survey respondents in industrial and developing countries. These data are gathered from a number of survey institutes, think tanks, nongovernmental organizations, international organizations, and private sector firms. The WGI do not reflect the official views of the World Bank, its Executive Directors, or the countries they represent. The WGI are not used by the Bank Group to allocate resources. See http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.aspx#reports.

This chapter assesses the Bank Group’s contributions to the governance and anticorruption (GAC) agenda in Ukraine through its support for the establishment and strengthening of anticorruption institutions and public financial management (PFM) reform. It also summarizes the Bank Group’s contributions to anticorruption in individual sectors (energy, health, social protection, and so on), with more details in chapters 3 and 4 and appendix A.

Anticorruption Institutions

Anticorruption was a key theme in both Bank Group–supported strategies (FY12–16 CPS and FY17–21 CPF), but concrete actions were limited before 2014. The 2012 CPS contained a frank assessment of the situation in the country and identified corruption and state capture as dominant impediments to sustained economic growth and shared prosperity. At the same time, the CPS did not prioritize core governance activities given the lack of government commitment. Instead, the strategy provided selective interventions on PFM (as discussed later in this chapter), deregulation, and strengthening the governance of municipal infrastructure services. The CPS also signaled a pause in budget support operations until there was, among other things, consistent progress on governance.

Bank Group engagement on anticorruption received a boost after 2014, when a comprehensive package of anticorruption laws established a set of new specialized apex anticorruption institutions.1 Responding to the new political situation, and capitalizing on broad international support for reform efforts in Ukraine, the World Bank strengthened its engagement on GAC and used a programmatic series of DPLs to advance several core policy reforms. Prior actions included measures to advance the adoption of the new asset-declaration system, strengthen verification arrangements for asset declarations, and improve external budget audits.

The FY17–21 CPF was more ambitious in its GAC agenda. It advocated a two-pronged strategy to address Ukraine’s GAC challenges. The first prong sought to build core governance institutions to systematically enhance the effectiveness of public sector operations. The second prong included support for sector-level reforms. The World Bank produced several influential ASA products, such as the 2018 state capture study (Balabushko et al. 2018), which introduced a new methodology for identifying captured sectors of Ukraine’s economy and measuring the economy-wide impact of capture. According to Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) interviews, the study generated broad public interest and was widely used by development partners and civil society organizations (CSOs).2

Figure 2.1. Control of Corruption

Source: Worldwide Governance Indicators database.

Note: Percentile rank indicates a country’s rank among all countries covered by the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI): 0 corresponds to the lowest rank, and 100 corresponds to the highest rank. WGI summarize views on the quality of governance provided by many enterprise, citizen, and expert survey respondents in industrial and developing countries. These data are gathered from several survey institutes, think tanks, nongovernmental organizations, international organizations, and private sector firms. The WGI do not reflect the official views of the World Bank, its Executive Directors, or the countries they represent. The WGI are not used by the Bank Group to allocate resources. The black bars indicate lower and upper bounds of 90 percent confidence interval.

The World Bank relied significantly on development partners (especially the EU and International Monetary Fund [IMF]) to provide capacity-building assistance to implement DPL-supported governance reforms. Between 2008 and 2020, there were no new World Bank project loans to facilitate the modernization of government systems and processes (for example, in PFM, public administration, e-governance, tax administration, decentralization, or the justice sector). IEG interviews with development partners indicated that additional project support from the World Bank would have been welcomed and could have helped close implementation gaps.

The establishment of legal and institutional foundations for fighting corruption was a central aspect of Bank Group support for GAC in Ukraine. Public sector transparency was enhanced by expanding access to budget and procurement information, introducing the electronic asset disclosure system, implementing e-procurement, opening various public registries, and making several data sets (including court decisions) publicly available. The National Agency on Corruption Prevention (NACP), created with technical support from the World Bank, operates a comprehensive and publicly accessible e-declaration system for the personal assets of all high- and mid-level officials. Since 2018, the NACP has successfully collected, processed, and made public about 800,000 e-declarations per year. This information has been used by other anticorruption institutions (such as the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine) and by the civil society. The World Bank, jointly with other donors and Ukrainian CSOs, supported NACP staff training and advocacy to assist with full implementation of the system. IEG interviews with local stakeholders, including anticorruption advocates and development partners, indicated that asset disclosure has influenced the behavior of specific groups of officials (such as judges). Other Bank Group contributions included support for anticorruption enforcement institutions through the Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative and advisory assistance to local CSOs such as the Anti-Corruption Action Center.

However, the impact of anticorruption legislation is hampered by a lack of reform of the judiciary (both courts and the prosecutor’s office). Although the legal framework for the judiciary was revised in 2015 through a package of constitutional amendments and new laws, implementation has been slow and partial, deepening public skepticism over the government’s commitment to reform. Judicial reforms have been mostly cosmetic, having been successfully neutralized by entrenched interests (Dubrovskiy et al. 2020). Enforcement of anticorruption legislation, particularly when high-level officials are involved, remains weak, fueling public cynicism and undermining the effectiveness of a range of anticorruption laws and initiatives. The courts have regularly blocked the investigation and sentencing of corrupt officials (Center for Insights in Survey Research 2021). As of July 2021, National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine has investigated 879 cases, made 584 formal accusations, and brought 325 cases to courts, but has secured only 56 convictions.3

The launch of operations of the High Anti-Corruption Court provides some reason for optimism. The World Bank, together with international and local partners, was instrumental in protecting the High Anti-Corruption Court law against attempts to water down its core clauses (such as the independence of the Court and selection of the judges), including by temporarily withholding financial support. In 2019, its first year of operation, the High Anti-Corruption Court accelerated the resolution of corruption-related cases (Savin, Mykolaychuk, and Center for Combating Corruption 2020). If sustained, this work would strengthen incentives within the law-enforcement community and civil society to investigate and publicize evidence of corruption.

Bank Group engagement in justice sector reform throughout the review period was limited to modest diagnostic work. The 2017 Systematic Country Diagnostic emphasized the importance of justice sector reform and noted that “building better anticorruption, justice, and public administration institutions [is] critically important for Ukraine and would have far-reaching ramifications for progress along each of the other development pathways” and “justice reform is an important component of strengthening governance in Ukraine and facilitating its aspirations of joining the [EU]” (World Bank 2017h, 44 and 48). Although organizations such as the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine, for example, can expose corruption cases, only a reformed judiciary can reduce systemic corruption (Oxenstierna and Hedenskog 2017). At the same time, the 2017 CPF stated explicitly that in justice sector reform (as well as in civil service reform and decentralization), the Bank Group would rely on other development partners (the EU and bilateral agencies) that were better placed to provide support, according to the CPF (World Bank 2017c). However, IEG interviews for this CPE revealed little evidence of effective coordination and complementarity with development partners in this area. For example, it was unclear whether the aspects of justice reform needed to make Bank Group–supported reforms effective (for example, for nonperforming loan [NPL] resolution in the banking sector) were to be prioritized (or even covered) by other partners.

Where the World Bank was active on the GAC agenda, there was coordination with donor activities and the World Bank was a source of relevant analysis. Donor coordination on the introduction of the new asset-declaration system at the NACP was particularly successful—the system was funded by the United Nations Development Programme, the World Bank provided technical assistance, the IMF supplied policy leverage, the EU and the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development provided support for system development.4 The World Bank mobilized additional grant funding to augment its ASA for governance and PFM reforms. The Department for International Development’s Good Governance Trust Fund allowed for the expansion of World Bank support in PFM and anticorruption reform. The World Bank also leveraged EU, German Agency for International Cooperation, and United States Agency for International Development resources to carry out Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA) assessments and disseminate their findings.

The Bank Group drew on the knowledge and experience of Ukrainian think tanks and CSOs in the design and implementation of its strategy. Historically, CSOs have played an important role in promoting the GAC agenda in Ukraine, and their successful cooperation with international donors was recognized as an effective “sandwich model” for advancing reforms.5 IEG identified a few instances of cooperation between the World Bank and Ukrainian CSOs on ASA and of integration of local knowledge providers into monitoring of reform implementation: the state capture study (Balabushko et al. 2018) with the Institute for Economic Research and Policy Consulting, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative with DiXi Group, and anticorruption advocacy and monitoring with Anti-Corruption Action Center.

Overall, Bank Group support to advance GAC reforms contributed to several positive outcomes. The Bank Group played an important role in the broad anticorruption coalition of development partners, civil society, and reform-oriented segments of government; was a key participant in a joint communications campaign (with other donors) to accelerate the adoption of key laws and regulations; and provided critical technical assistance to build capacity in new apex anticorruption institutions. The World Bank used sectoral reform programs (for example, in energy, health, and banking) to advance the GAC agenda. Table 2.2 summarizes anticorruption progress at the sector level with the help of the World Bank. More details on specific sector engagement are given in chapters 3 and 4 and appendix A.

However, the concrete impact of Bank Group–supported GAC reforms in Ukraine has been modest. The establishment of many high-level anticorruption institutions was a step in the right direction and held the promise to create “islands of integrity” in the public sector. However, these institutions have yet to make a systemic impact. The effectiveness of Bank Group–supported reforms on GAC is undermined by weaknesses in the overall quality of public administration and by a lack of progress on reforming the judiciary. The World Bank’s decision not to engage actively in the justice sector underestimated the severity of the development constraints imposed by a dysfunctional court system, including in addressing specific sector constraints such as NPL and debt resolution, tax collection, and state-owned enterprise reform. Political opposition to anticorruption policies remains strong, which is illustrated by the fact that the core anticorruption legislation has faced multiple challenges in courts.

Table 2.2. Summary of Anticorruption Reforms in Sector Programs

|

Sector |

Main Achievements |

World Bank Group Contributions |

Unfinished Agenda |

|

Banking |

Reform of the legal and institutional frameworks in the sector reduced corruption risks in supervision and opportunities for money laundering and ensured greater transparency in banks’ ownership. |

The World Bank Group provided support through DPLs, ASA, and technical assistance to develop and adopt the legal and institutional frameworks and improve institutional capacity of the National Bank of Ukraine and the Deposit Guarantee Fund. |

Governance arrangements for state-owned commercial banks remain weak. |

|

Gas supply and distribution |

Reforming governance structures in the sector led to greater transparency (for example, in the allocation of new gas licenses) and reductions in corruption opportunities and illicit practices. |

Policy and institutional reforms through DPLs (prior actions promoting institutional and tariff reforms, including restructuring of key sector entities) provided advisory and technical support for unbundling the state-owned gas monopoly (Naftogaz), improving capacity of the regulator, and reforming the tariff and subsidy system. |

Regulation of regional gas distributors needs to be strengthened. |

|

Other energy and utilities |

Implementation of the EITI and improved payment and contract disclosure led to increased transparency in the sector, including in the operations of several municipal utilities (district heating, water), reducing opportunities for corrupt practices. |

The Bank Group provided technical assistance for EITI implementation and financed development and implementation of better payment and contract disclosure systems. |

Weaknesses in regulation of electricity and coal markets (which affects transparency of pricing); considerable variation in transparency across municipal utilities; need to impose and enforce stricter across-the-board performance standards by the regulator. |

|

Health |

Pharmaceutical procurement reform, including creation of a national purchasing agency, the NHSU, and new provider payment rules replaced a system conducive to corruption through opaque procedures for the allocation of budget funding. |

The Bank Group supported the pharmaceutical procurement reform and the establishment of the NHSU through a health sector investment project, “Serving People, Improving Health,” and accompanying ASA (for example, social accountability tools for CSOs monitoring municipal services and procurement) in Ukraine, providing technical assistance and financing. |

Extending new provider payment rules beyond primary care to hospitals; solidifying the position of transparent contracting and drug procurement mechanisms so that they are not bypassed by COVID-19 emergency arrangements. |

|

Social protection |

Reform measures (introduction of means testing, monetization of some benefits, and enhanced central control over local governments’ compliance with the established rules of benefit administration) led to reduced opportunities for corruption in the social benefit administration. |

Bank Group projects and ASA supported capacity-building measures within the administration and ongoing advisory and technical assistance. (For example, Bank Group contributions included analytical, modeling, and simulation work on parametric changes to the household utility subsidy.) |

Sustaining momentum for improved targeting of benefits and expanding the guaranteed minimum income. |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: ASA = advisory services and analytics; CSO = civil society organization; DPL = development policy loan; EITI = Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative; NHSU = National Health Service of Ukraine.

Public Financial Management

The World Bank was an effective contributor to strengthening PFM and increasing the transparency of public finance in Ukraine, especially since 2015, within a broad coalition of international partners. The World Bank played a key advisory role and used DPLs to advance several key pieces of legislation, including amendments to the budget code and a new law on the Accounting Chamber in 2015, which laid the foundation for the Chamber to strengthen its independence and expand its mandate. Although the World Bank’s role in the delivery of day-to-day technical assistance was relatively modest, the Bank Group was an influential adviser to the Ministry of Finance and made a substantial contribution to the design of the government’s PFM reform strategy for 2017–20.

PEFA assessments in 2012 and 2019 provided a comprehensive picture of the progress made by Ukraine in PFM (World Bank 2012c, 2019c).6 Ukraine demonstrated good progress over the evaluation period in transparency and accountability arrangements within the PFM system, such as public access to information, transparency in public procurement, predictability of transfers to local budgets, and the quality of internal controls and external audits. Overall, 21 of the 31 PEFA indicators improved. Importantly, the score for internal controls on nonsalary expenditures increased from B to B+. Although Ukraine lags most of its neighbors on many governance indicators, its Open Budget Index score (a consolidated measure of budget transparency) increased from 54 (out of 100) in 2012 to 63 in 2019 and is either better than or similar to the scores of many EU member countries in Eastern Europe.7 PEFA 2019 (World Bank 2019c) laid the basis for the current government’s 2021–24 PFM reform strategy.

Progress in PFM contributed to a rationalization of public spending in pensions, social protection benefits, and energy subsidies. The World Bank supported the government in strengthening key building blocks of the PFM system, including the automation of budget planning and the establishment of the integrated Human Resources (and Payroll) Management Information System through the Strengthening Public Resource Management Project (FY17), funded by an EU grant. However, a more comprehensive rationalization of public spending has been hampered by slow implementation of the Human Resources (and Payroll) Management Information System.

Major steps were taken to make Ukraine’s public procurement system more efficient and transparent and less susceptible to corruption. This was achieved through the implementation of the e-procurement system (ProZorro),8 enabled by the new public procurement law. This law, updated with technical assistance from the World Bank and adopted in December 2015, aligns national procurement regulations with EU directives and regulates the application of e-procurement. The general public now has easy access to information on public procurement. The number of business entities registered with ProZorro as actual and potential bidders increased from 64,000 in 2016 to 240,000 in 2020, reflecting strong expansion in small and medium enterprise interest in participation. The share of competitive public procurement almost doubled by 2018 (from 35 percent in 2013), exceeding the first DPL (2014) target of 55 percent (Smits et al. 2019; World Bank 2019c). Annual savings from more competitive procurement were estimated by the Ministry of Finance at 0.7 percent of GDP in 2019 (Ministry of Finance of Ukraine 2019).

Some progress was made in public investment management (PIM) through establishing, and ensuring compliance with, more transparent project-selection procedures. Most central government public investment projects since 2016 have been appraised and selected through a transparent process (tracked through a results indicator in the first and second DPLs and supported by World Bank technical assistance, including a PIM assessment and PEFA update). According to IEG interviews with government partners, the World Bank was one of the few international partners that maintained a long-term institutional engagement on PIM. The annual budget execution rate for public investment projects increased from 70 percent in 2010 to 91 percent in 2019, exceeding the CPS target of 80 percent. However, according to PEFA 2019, PIM is still one of the weakest elements in the country’s PFM system, lacking strategic and transparent allocation of overall resources. It was rated C+ in 2019, up from D+ in 2015, with the score for investment project costing decreasing to D in 2019 from C in 2015 (World Bank 2019c, 47). Investment spending remains fragmented because many ad hoc investment projects are still not subject to the established competitive selection procedures. The total costs of such projects are nearly double the value of properly selected investments (World Bank 2019c).

- These institutions included the National Anti-Corruption Bureau with investigative functions, the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office to prosecute high-level corruption crimes, and the National Agency on Corruption Prevention, which is responsible for verifying the asset declarations of public officials and implementing conflict-of-interest provisions.

- Other influential advisory services and analytics products included regular policy notes, public finance reviews (World Bank 2017g, 2018d), and a growth study (Smits et al. 2019).

- See https://nabu.gov.ua/en.

- In September 2020, the Department for International Development was replaced by the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office.

- “Sandwich model” describes a partnership in which domestic civil society elaborates on policy ideas and implementation while the international community presses the political elite into adopting reforms (Nitsova, Pop-Eleches, and Robertson 2018, 7).

- Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability assessments measure the ability of public financial management processes and institutions to contribute to desirable budget outcomes, aggregate fiscal discipline, strategic allocation of resources, and efficient service delivery. They include 31 key components in seven broad areas, each measured by a four-grade scale on which D is the lowest and A the highest score.

- In 2019, Ukraine scored 63 on the International Budget Partnership’s Open Budget Index (0–100), compared with 64 for Romania, 60 for Poland and the Slovak Republic, and 59 for Czechia (International Budget Partnership 2020).

- ProZorro is a locally developed, low-cost information technology solution that was launched in 2015 with support from civil society. It provides comprehensive procurement coverage of the public sector, including subnational governments and major nonbudget entities. During 2016–18, the annual number of procurement tenders quadrupled, and their value tripled. The system is fully sustainable as it is funded by users’ (bidders’) fees.