The World Bank Group in the Kyrgyz Republic

Chapter 2 | World Bank Group–Supported Strategies, Fiscal Years 2014–21

Highlights

The Country Partnership Strategy, fiscal years 2014–17, with the overarching theme of improving governance (focusing on public administration, public service delivery, and the business environment), was well aligned with the country’s development challenges. However, the objectives were overly ambitious given the country’s political and governance context.

A shift in emphasis toward private sector–led growth, and away from governance, began in fiscal year 2016 and continued with the Country Partnership Framework, fiscal years 2019–22.

The focus on private sector–led growth was relevant to the country context, but the pivot away from governance undermined pursuit of this objective given that governance challenges were a major deterrent to private sector activity.

In the wake of the 2010 political crisis, international development partners drafted a joint economic assessment to coordinate assistance. The assessment—led by the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, and the International Monetary Fund, with the participation of the Eurasian Development Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the European Commission, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), and the United Nations—focused on addressing the country’s post-conflict needs for budget support, humanitarian aid, and infrastructure repair and rehabilitation (ADB, IMF, and World Bank 2010). Beginning in 2012, the Bank Group work was informed by the FY12–13 Interim Strategy Note (World Bank 2011a), which recognized that corruption, nepotism, and misuse of public assets had been fundamental causes of the 2010 crisis.

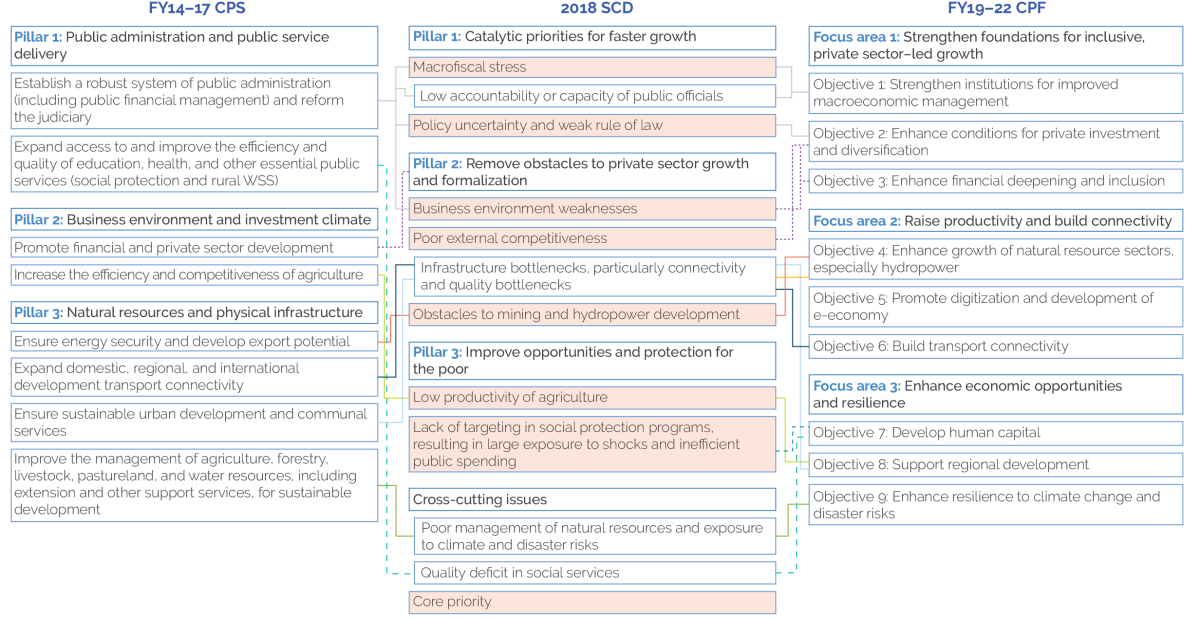

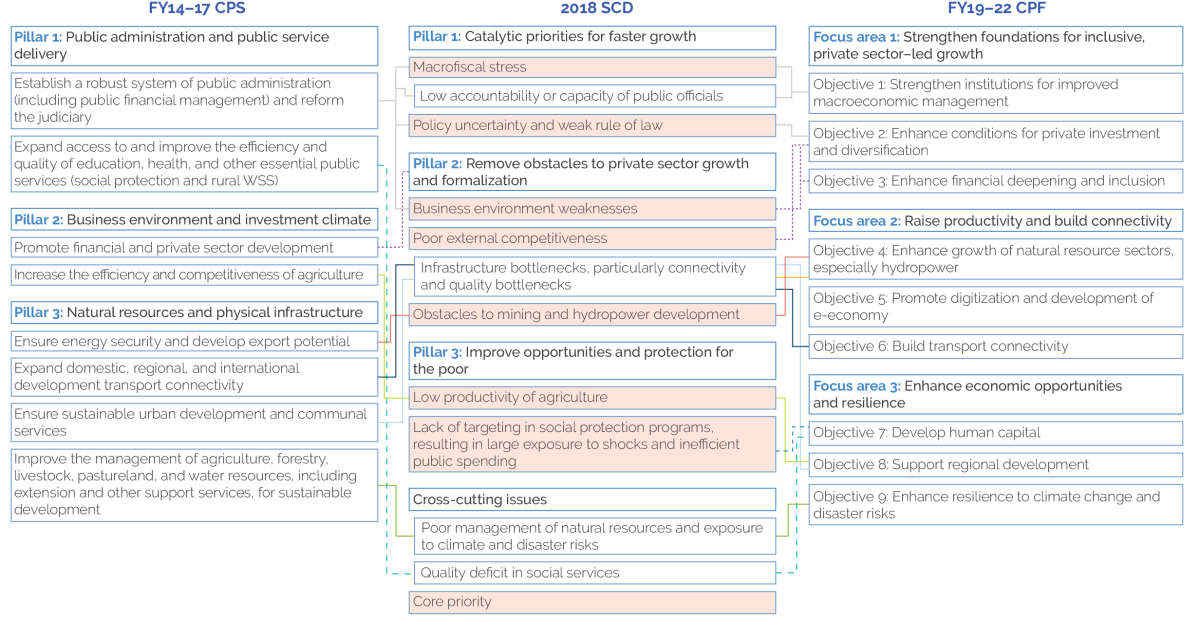

The FY14–17 CPS for the Kyrgyz Republic marked the Bank Group’s return to a standard partnership framework, with a focus on governance, which was described as the country’s “overriding development challenge” (World Bank 2013b, 1). The CPS stated that “the dispersion of responsibility under the 2010 constitution, patronage rivalries, an assertive parliament, significant street protests, and coalition politics circumscribe[d] the government’s ability to take difficult but necessary decisions” (World Bank 2013b, 34). The CPS set out to support governance reforms that would reinforce state accountability and legitimacy through the use of a conflict and fragility filter in new and ongoing lending operations. This approach was well aligned with the country’s development challenges and the government’s strategy. The focus on public administration, public service delivery, and the business environment was appropriate for the context of weak governance and the need to promote private sector–led growth to address the country’s economic vulnerabilities. Out of the 43 objectives in the National Sustainable Development Strategy, CPS objectives addressed 26 (60 percent) of them. Figure 2.1 presents the CPS objectives, priorities identified in the Systematic Country Diagnostic (SCD), and FY19–22 CPF objectives.

The CPS governance agenda was ambitious. It aimed to build a meritocratic public administration; reduce corruption through the anticorruption action plan and implementation of the Law on Conflict of Interest; improve access to justice; support improvements in public financial management (PFM); and make public procurement more transparent.

With respect to financial and private sector development, the CPS aimed to improve financial sector stability, further the development of credit bureaus and the use of movable assets as collateral, expand financial services through the Kyrgyz Post Office (KPO) and through the transformation of microfinance institutions into banks, improve access to finance in the agriculture sector, and improve the investment climate and the food safety framework. It did not target improvements in firm capabilities despite this being a major development constraint.

Expanding access to and increasing the efficiency and quality of education, health care, and other essential public services were among the CPS objectives. This included education and health services, water supply and sanitation (in rural and urban areas separately), solid waste management in urban areas, and other social infrastructure. The CPS did not directly address the drivers of low-quality essential local public services; however, it did state that it would work in urban areas to strengthen the capacity of local governments in beneficiary communities.

The February 2016 PLR concluded that “the pace of program and project execution has been slower than envisaged largely due to institutional and capacity constraints, which were exacerbated by frequent changes in government,” among other factors (World Bank 2016c, 1). In addition, “whilst successive governments expressly endorsed the strategic directions of the CPS, shifts in priorities and in the intensity of commitment to specific reforms resulting from frequent changes of leadership . . . [and other issues] often led to loss of cohesion and momentum in achieving the CPS outcomes. . . . Power dynamics between the executive and legislative branches of government led to inordinate delays in approving major reforms. It also contributed to lengthy procedures for adopting and ratifying international financing agreements, which in turn undermined the timeliness and quality of World Bank portfolio” (World Bank 2016c, 5).1

Figure 2.1. Mapping of FY14–17 Country Partnership Strategy, Priorities in the Systematic Country Diagnostic, and FY19–22 Country Partnership Framework

Figure 2.1. Mapping of FY14–17 Country Partnership Strategy, Priorities in the Systematic Country Diagnostic, and FY19–22 Country Partnership Framework

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: CPF = Country Partnership Framework; CPS = Country Partnership Strategy; FY = fiscal year; SCD = Systematic Country Diagnostic; WSS = water supply and sanitation.

In addition, by the PLR stage, the Kyrgyz Republic was facing a series of economic shocks.2 In response, the Bank Group decided to shift attention to growth and jobs to help the Kyrgyz Republic take advantage of the opportunities emanating from membership in the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and from improved prospects for broader regional cooperation in Central Asia and to address sources of macroeconomic vulnerability, including in fiscal and financial sector management.

However, the shift envisioned at the 2016 PLR stage to strengthen the focus on private sector–led growth was only partially implemented. The PLR added the Dairy Sector Program to link farmers with markets and strengthen capacity to comply with EAEU standards. This marked a transition from projects focused on productivity in primary agriculture to those that addressed constraints along the value chain. However, plans to create a level playing field for SMEs, implement entrepreneurship programs to help firms export and grow, and support trade facilitation–related investments were not followed up on.

The 2018 SCD focused on the constraints to adjusting the Kyrgyz economic development model to one with more diverse sources of growth driven by the private sector. At the same time, the SCD confirmed the earlier conclusion that long-term stability and growth depend on tackling governance or corruption challenges and that “governance is the main bottleneck for private sector growth” (World Bank 2018c, 18). The SCD also argued that a more predictable investment climate was needed (World Bank 2018c).3

To support this new development model, the SCD identified seven core constraints to development and growth that needed to be addressed: macrofiscal stress, business environment weaknesses, weak external competitiveness, obstacles to mining and hydropower development, low agricultural productivity, lack of targeting in social protection programs, and policy uncertainty and weak rule of law.4

Informed by the SCD, the FY19–22 CPF focused on the following:

- Strengthening foundations for inclusive, private sector–led growth (focus area 1). This consisted of the following objectives: strengthen institutions for improved macroeconomic management, enhance conditions for private investment and diversification, and enhance financial deepening and inclusion.

- Raising productivity and building connectivity (focus area 2). This included the following objectives: enhance growth of natural resource sectors, especially hydropower; promote digitization and development of e-economy; and build transport connectivity.

- Enhancing economic opportunities and resilience (focus area 3). This consisted of the following objectives: develop human capital, support regional development, and enhance resilience to climate change and disaster risks.

The CPF significantly narrowed the scope of Bank Group support for governance reforms. It dropped attention to civil service, judicial, and anticorruption policy reform. Its objective to “strengthen institutions for improved [macroeconomic] management” focused narrowly on fiscal discipline and PFM (World Bank 2018a, 15), and the objective on digitization focused on improvement in tax administration through the e-filing rate of value-added tax (VAT) returns. This was a marked departure from the broad scope and central nature of governance in the CPS. According to interviews with Bank Group staff, this shift was driven largely by the perceived lack of ownership for core governance reforms within the new administration and by the realization by World Bank management that earlier World Bank efforts to advance such reforms without strong government buy-in had had limited traction. According to interviews with World Bank staff, there was also a desire to reduce the share of risky governance projects in the portfolio to accelerate disbursements and raise disbursement ratios.

However, the country was facing the same set of governance challenges as before, with negative implications for economic growth and diversification. The joint economic analysis, Interim Strategy Note, CPS, 2016 PLR, and 2018 SCD all argued that governance was the primary obstacle to achievement of development objectives. Indeed, the CPF recognized a need to “address poor governance and institutional quality[,] especially [macrofiscal] stress, weaknesses in the rule of law, and the limited accountability/capacity of public institutions and officials” (World Bank 2018a, 9), and it indicated that the “thrust on institutions and governance reforms will be maintained in a cross-cutting way” (World Bank 2018a, 15). However, the CPF explicitly excluded justice sector reform from the program, despite its criticality to the effective implementation of governance reform. The shift was reflected in the drastic reduction in the number of governance indicators and targets in the CPF results framework (compared with the CPS results framework).

Continuing the shift that began with the PLR, the FY19–22 CPF narrowed the CPS objectives that did not have an explicit focus on economic growth to link them more closely with this goal. This was done through the following (see figure 2.1):

- Greater attention was given to regional development (objective 8), focused on Issyk-Kul in the north and Osh, Jalal-Abad, and Batken in the south. This objective encompassed agriculture commercialization, rural livelihoods, and local infrastructure to support private investment.

- Promoting the development of e-economy (objective 5) was a new objective.

- Support for transport connectivity included a link with tourism, and attention to air connectivity was added.

- The motivation for improving the management of natural resources narrowed to enhancing resilience to climate change and disaster risks (objective 9).

- The objective of improving access to and improving the efficiency and quality of education, health, and other essential public services in the CPS became more narrowly focused to develop human capital, linked to labor markets (an economic growth issue) and child and maternal health (a core human development issue).

The CPF objective to enhance conditions for private investment and diversification included a broad range of activities. Support for PFM (including improving the transparency of budget processes, public investment management, and procurement) sought to bolster competitiveness, although precisely how this would be achieved was not explained. An IFC advisory on the investment climate included support to improve laws, regulations, and sector-specific enabling regulation. The objective also included strengthening corporate governance and enhancing audit and financial reporting. However, during the internal review process, reviewers pointed out that some CPF results indicators targeted de jure laws and regulations rather than de facto changes and that the level of ambition for this objective appeared to be low overall.

IFC aimed to support all three CPF focus areas to enhance the investment climate, improve corporate governance, potentially support privatization, develop sustainable agribusiness and value chains, deepen and diversify the financial sector, and enable private investments and public-private partnerships. The CPF noted that expansion of IFC’s investment program depended greatly on the government’s continuation of reforms to improve the business environment, governance, and institutional capacity.

Both the CPS and the CPF envisioned a limited role for the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA). The CPS mentioned that the proposed Kemin-Almaty transmission line, if funded by private investors, could possibly receive MIGA assistance, but that MIGA would be ready to “deploy its risk insurance products in the Kyrgyz Republic in the promising mining and hydropower sectors, provided improvements in governance and application of investment laws occur” (World Bank 2018a, 31).

Attention to the provision of local public services was less prominent in the FY19–22 CPF. The only local service explicitly referenced in the strategy was rural water supply and sanitation, where it noted that “existing operations in . . . rural water supply and sanitation . . . are already aimed at increasing efficiency, quality, productivity, and resilience and, hence, provide a sound basis to support the CPF objective of diversified, export-oriented, inclusive, and resilient growth” (World Bank 2018a, 15). Urban services were not a significant part of the CPF because they were being supported by the EBRD. No mention was made of the constraints impeding local government’s ability to deliver local public services despite the continuation of a large portfolio of interventions designed to improve local public services.5 The FY19–22 CPF results framework also gave limited attention to essential local public services, with only one indicator for this area—the “number of people provided with water supply services under the Sustainable Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Project” (World Bank 2018a, 46).

- It took an average of 13 months after the Board of Executive Directors’ approval for World Bank projects to become effective.

- Lower gold prices, a regionwide economic slowdown, and currency depreciations that affected the Kyrgyz Republic economy through trade, remittances, and foreign direct investment channels.

- This was similar to the assessment in the International Monetary Fund Country Report “Kyrgyz Republic: Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper—Country Development Strategy (2007–2010)” that argued, “Investment climate in [the Kyrgyz Republic] is inefficient and unpredictable. Almost all of the sectors of economy are in shadow. . . . [G]old deposits at Kumtor are being depleted. . . . Therefore it is crucial for [the Kyrgyz Republic] to diversity [sic] economic growth sources and to ensure its long-term sustainability” (IMF 2007, 5).

- Other constraints that the Systematic Country Diagnostic identifies but does not prioritize as core for the short term are low accountability or capacity of public officials; infrastructure bottlenecks, particularly for connectivity; quality deficit in social services provision; inadequate management of natural resources; and exposure to climate and disaster risks.

- The Second Village Investment Project, $40.8 million, fiscal years (FY) 2007–15; the Bishkek and Osh Urban Infrastructure Project, $27.8 million, FY08–16; Urban Development Project, $12 million, FY16–22.