The World Bank Group in Bangladesh

Chapter 2 | World Bank Group–Supported Strategies

Highlights

Two strategies underpinned the World Bank Group’s engagement in Bangladesh over the evaluation period—the Country Assistance Strategy for fiscal years 2011–15 and the Country Partnership Framework for fiscal years 2016–20. Bank Group support was streamlined at the Country Assistance Strategy Progress Report (November 2013) but expanded toward the end of the evaluation period, partly in response to two major shocks (Rohingya refugee crisis and coronavirus global pandemic), resulting in a large and diverse program by the end of the review period.

Bank Group internal coordination was strong. There was complementary work across the three institutions, particularly in the energy sector. Joint work with the International Finance Corporation was notable on the investment climate agenda and in the financial sector, although much effort failed to gain traction with the authorities. Greater internal synergies could have been leveraged in transport, health, and urban service delivery.

The World Bank’s relationship with development partners was productive, notably through the sectorwide approach in education and health and in addressing the Rohingya displaced population crisis. The World Bank leveraged its comparative advantage in knowledge work, monitoring and evaluation, and fiduciary oversight.

World Bank Group Strategies and Objectives

The 2015 SCD identified constraints to development in energy, inland connectivity, and weak public institutions that Bangladesh needed to address to achieve its official goal of upper-middle-income status. Weaknesses in the banking sector—including in governance, high and growing NPLs, and undercapitalized banks—posed significant financial and quasi-fiscal risks. High poverty rates persisted in areas with inadequate infrastructure and low human capital. Bangladesh ranks low in infrastructure quality among its peers (Global Competitiveness Report, Schwab 2019), with quality undermined by low maintenance budgets. Underinvestment in infrastructure was a binding constraint to growth, and access to services (such as water and sanitation, roads, and electricity) was inadequate.

Two strategies underpinned the Bank Group’s engagement in Bangladesh over the review period. These were the CAS for FY11–15, updated in November 2013 through a CAS Progress Report (CASPR), and the CPF for FY16–20, updated in January 2020 after a Performance and Learning Review (PLR), which also extended the CPF period to June 2021. Bank Group support to Bangladesh was informed by the government’s Vision 2021 (Center for Policy Dialogue 2007) and by the 2015 SCD (World Bank 2015a).

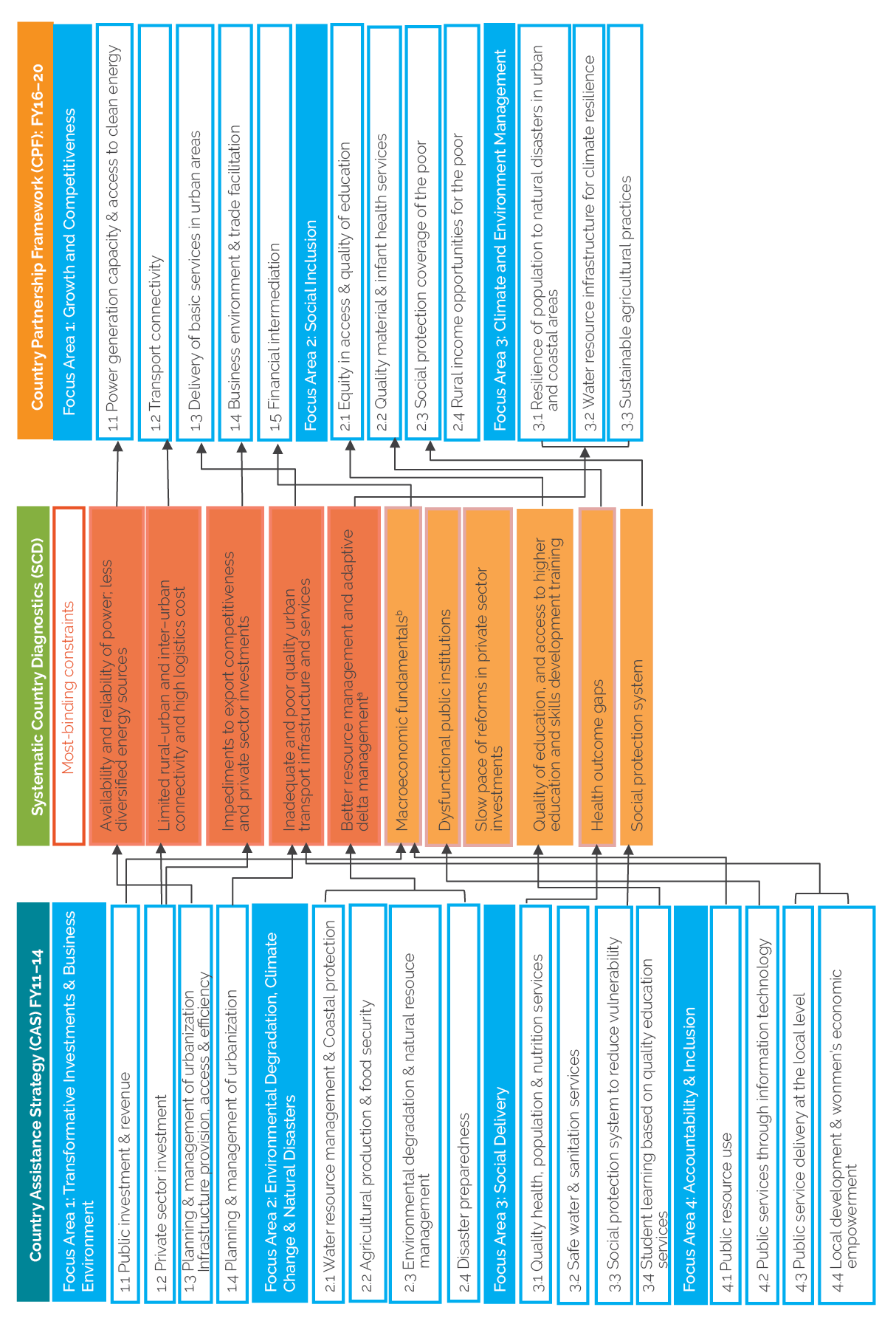

Bank Group engagement in Bangladesh evolved but remained substantially concerned with three key focus areas: growth and competitiveness (focus area 1), social service delivery and inclusion (focus area 2), and climate and environmental management (focus area 3). Figure 2.1 depicts the evolution of Bank Group–supported objectives at the CAS and CPF stages (while changes at the CASPR and PLR are discussed in the paragraphs that follow).

The FY11–14 CAS sought to address the country’s development challenges through 16 objectives in four broad areas: transformative investments and business environment, environment and climate change, social delivery, and accountability and inclusion. The CAS had three cross-cutting themes: regional cooperation, gender mainstreaming, and aid effectiveness. The objectives reflected the Bank Group’s support for the government’s policy agenda and its optimism as the country transitioned to greater political stability. However, the wide range of objectives also reflected a lack of selectivity and focus. Bank Group support for the financial sector was mainly provided through analytical work and technical assistance on Anti-Money Laundering / Combating Financing of Terrorism and a review of standards and codes on insolvency. The government’s Sixth Five Year Plan (2010–14) financial sector strategy included strengthening the regulatory framework, deepening financial markets, enhancing financial inclusion, implementing Basel capital requirements of banks, and automating the credit information bureau. Fiscal reform received little attention, possibly reflecting the focus on this area in the IMF-supported program.

At the CASPR (FY14), the CAS program was consolidated and objectives were reduced to 11 in recognition of implementation challenges, including the cancellation of the Padma Bridge project.1 Five of the 16 CAS objectives were dropped to reflect slippages in the lending program (including the objective of expanded access to safe water and sanitation services) or due to limited progress toward targeted outcomes (as in the case of public investment and revenue generation). Some other CAS objectives were either revised or merged with other objectives.

The FY16–19 CPF retained three of the four CAS focus areas (growth, social inclusion, and climate resilience) while addressing governance as a cross-cutting theme. It added objectives related to financial intermediation, trade facilitation, and urban service delivery. Little focused attention was given to fiscal vulnerabilities, including those associated with the SOE sector. However, analytical work by the World Bank, with emphasis on fiscal issues (a Country Economic Memorandum and a Public Expenditure Review), was begun during FY20–21, which may open the way for a deeper policy dialogue and engagement on fundamental fiscal reforms. The number of objectives expanded to 12 (from 11 objectives at the CASPR). At the PLR stage (FY20), two objectives were added in response to emerging issues such as the influx of the displaced Rohingya population. Adjustments were also made to existing objectives and targets due to slippages in implementation (including in transport connectivity).

There was modest attention to the financial sector in the CPF, according to which improving corporate governance and financial performance of SOCBs and the overall regulatory and supervisory capacity of the banking sector were vital for sector stability. As part of the CPF, the World Bank approved the Modernization of State-Owned Financial Institutions Project to contribute to the modernization, transparency, and efficiency of SOCBs. However, the project was canceled after approval by the Bank Group’s Board of Executive Directors when it failed to obtain the approval of the Executive Committee of the National Economic Council, which is headed by the prime minister. The CPF indicated that IDA support to strengthen the foundations of Bangladesh’s financial system would be “complemented by [the International Finance Corporation’s] private sector investments through long- and short-term finance, mobilization, and capital market instruments focusing on critical infrastructure” and that the International Finance Corporation (IFC) would “also focus on strengthening the banking sector by providing long-term financing” (World Bank 2016b, 23).

The CPF’s modest attention to the financial sector reflected the government’s confidence in the strength of the banking sector. Ministry of Finance and central bank officials interviewed for this evaluation considered the Bank Group’s concerns overstated, citing as evidence Bangladesh’s experience in favorably weathering the 2008–09 global financial crisis, the declining share of SOCBs in the financial sector, and a belief in the capacity of Bangladesh’s government to bail out any state-owned or private commercial bank in the event of a default. The central bank was explicitly counting on faster private bank growth (relative to SOCB growth) to enhance banking system stability through private commercial banks’ better management of asset quality (Bangladesh Bank 2018, xxi). However, the strength of this strategy was undermined by weakened supervisory independence,2 revisions to definitions of asset quality (that resulted in underreporting of NPLs), and significant ownership of private banks by strongly connected interests.

Figure 2.1. Evolution of Bank Group Engagement from the Fiscal Years 2011–14 CAS, 2015 SCD, and Fiscal Years 2016–19 CPF

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: CAS = Country Assistance Strategy; CPF = Country Partnership Framework; FY = fiscal year; SCD = Systematic Country Diagnostic.

Red box: These are the most binding constraints or what SCD called transformational priorities. Concerted action in the next 3–5 years could have transformational impact on the pace of progress towards eliminating poverty and boosting shared prosperity. These are areas where Bangladesh lagged behind Asian peers. Orange box: Labelled as “foundational priorities” by SCD. These are prerequisites for faster growth and job creation which Bangladesh has addressed reasonably well in recent years.

a. Includes improving productivity, crop diversification and reduce vulnerability to climate change.

b. Includes strengthening tax system, improving health of financial sector and enhancing financial intermediation.

Program Design

The Bank Group deployed the full range of instruments to support the government’s program, including IFC investments and advisory services and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) guarantees. Where there was a lack of client interest in reform, analytical work and advisory services were usually pursued to maintain an up-to-date understanding of challenges, sustain a dialogue with the government, and (particularly in the case of the financial sector) prepare the ground for quick response if and when a window of opportunity opened.

The World Bank scaled up well-performing operations in education, health, rural roads, rural energy, and local government through the use of additional financing. Several development policy operations were approved toward the end of the CPE period (FY19–20) to support the jobs agenda, but they did not meaningfully confront rising macroeconomic and financial sector stresses. The limited role played by budget support operations reflected the government’s reluctance to undertake economywide fiscal, financial, trade, and energy sector reforms and was in sharp contrast with the preceding decade, when policy-based lending played an important role in the World Bank’s portfolio.

Five Program-for-Results (PforR) projects were approved during the second half of the CPE period to advance reforms in tax administration, public finance management, education, and transport. All five PforR operations experienced implementation delays caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, but there were implementation issues before the pandemic as well. For example, the first PforR (on value-added tax) suffered a major setback after the government’s reversal of associated reforms in 2016, which required a retrofitting of value-added tax online systems and contributed to implementation delays. In the case of the rural bridges project, implementation was affected by procurement delays in civil works and consultancy services and project management turnover.

The CAS results framework reflected the Bank Group’s ambition to support “transformative” investments while at the same time continuing long-standing engagement in education, health, and rural development. The framework was streamlined at the CASPR stage to reflect changes in the relationship with the authorities after the cancellation of the Padma Bridge project and the pause on new lending for large infrastructure projects. The CPF results framework reflected a reengagement in large infrastructure investments and the introduction of climate and natural resource management as a focus area. Further adjustments were made at the PLR stage, including the addition of a new objective related to support for the Rohingya refugee population and the dropping of an objective for improved water resources when the planned intervention did not materialize. The River Management Improvement Program was negotiated but later dropped. Several results indicators in transport and education were also dropped. There were no fiscal results indicators in the CPF. The only aspect of financial sector performance that was formally tracked was financial inclusion, though it was an important aspect.

There were several shortcomings in the results frameworks used to monitor progress toward the objectives of the Bank Group–supported strategy. First, there was a lack of measurement of learning outcomes for primary education despite two decades of engagement and significant investments in projects and analytical work by the World Bank. The results framework also did not capture the impact of contributions from higher education and skills training interventions, which had been in the portfolio for a decade. Results from governance interventions were not captured, including those associated with projects in the portfolio before and during the CPE period (for example, Local Government Support Project, procurement, and value-added tax). Second, some of the results indicators did not adequately capture the substance of the objectives. For example, indicators for food security and resilience were output oriented rather than outcome oriented or were too broad given the scope of World Bank–supported interventions. The results indicator for transport connectivity was narrow in scope and reflected only the rural access dimension, not the broader objective (regional and waterway connectivity). Third, some new interventions, such as in livestock and forestry, were not well linked to objectives. Finally, there was limited integration of IFC and MIGA interventions in the results frameworks, although this was rectified at the PLR stage to reflect IFC engagement in energy and financial services.

Flexibility and Responsiveness

The early phase of the Bank Group’s engagement started with an ambitious program, which was significantly impacted after the cancellation of the Padma Bridge project. The project’s cancellation strained the Bank Group’s relationship with the authorities and led to a temporary pause in new borrowing from the World Bank for large infrastructure projects. The Bank Group redirected its support to human development projects and continued its support for rural transport and rural energy. In the second half of the CPE period, the Bank Group resumed lending for large investments in energy and transport.

The Bank Group–supported program was adjusted to what the government was willing to implement. Projects that had been approved by the World Bank Board of Executive Directors (including those related to financial modernization and water resource management) were later dropped due to changing government priorities and lack of commitment to reform. The Bank Group responded well to government requests, including one request to address the influx of displaced Rohingya to Bangladesh in 2017 (box 2.1) and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

Box 2.1. World Bank Group Support during the Rohingya Refugee Crisis

The World Bank’s support during the Rohingya crisis was informed by the Rapid Impact, Vulnerability and Needs Assessment funded by the World Bank’s Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery. The assessment informed early discussion with the government and development partners about recovery interventions and underpinned the World Bank’s Emergency Multi-Sector Rohingya Crisis Response Project. The World Bank also generated analytical work through the Cox’s Bazar Analytical Program to inform the medium-term policy response to the Rohingya crisis and the development of the host community, Cox’s Bazar. During the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, the program was adapted to provide just-in-time briefs on the impact of the pandemic on the Rohingya camps and Cox’s Bazar.

The International Development Association provided more than $500 million through its refugee subwindow to support the government’s response to the Rohingya crisis to meet immediate and broader economic and social needs of the 1.1 million displaced Rohingya and 336,000 residents in the host communities. To ensure effective coordination, the World Bank appointed a dedicated staff to work with the government, the United Nations, nongovernmental organizations, and other agencies.

Using existing systems, interventions addressed both the needs of the refugees and the host communities with regard to education, health, social protection, infrastructure, and gender-based violence. Interventions are relatively recent (since 2018). Despite implementation delays due to COVID-19, initial results suggest good progress overall. Some projects have been reprogrammed to support prevention of and response to COVID-19 for the Rohingya refugees and host communities. See details on implementation in chapter 4.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Risk Identification and Emerging Vulnerabilities

The Bank Group’s ex ante assessments of risks to the achievement of development objectives showed increasing risks to both portfolio and program. Risks identified in the CAS—such as faltering commitment to reforms, weak institutional capacity, and corruption—were rated from substantial to high throughout the evaluation period. However, risks from macroeconomic and sector strategies were rated as moderate.

The moderate macroeconomic risk rating contrasted with growing fiscal and financial vulnerabilities in the second half of the CPE period, many of which had already been flagged early on in the evaluation period. The 2010 Public Expenditure Review was particularly clear and forthright in this regard. It recognized fiscal vulnerabilities associated with persistently weak tax revenue collection, rising and poorly targeted subsidies, unfunded public sector pension systems, weak and inefficient SOEs and banks, a large volume of outstanding sovereign guarantees issued, policy and institutional weaknesses in government debt management, and deteriorating credibility of the budget. Several of these were echoed in Bangladesh Development Updates in 2012 and 2013.

Vulnerabilities increased after the completion of the IMF-supported program. Although Bangladesh’s fiscal deficit was being contained below 5 percent of the GDP, this was achieved through slower-than-programmed implementation of the Annual Development Program (with negative implications for potential growth). The current expenditure-to-GDP ratio was increasing, driven by high growth in wages, interest payments on increasingly less concessional debt, subsidies, transfers, and large, unplanned expenditures resulting from the Rohingya refugee crisis and then in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Uncertainty was further compounded by inadequacies of expenditure accounting, which resulted in the overstatement of growth. According to the 2013 CASPR, macroeconomic risks were to be mitigated through joint monitoring with the IMF. However, with the IMF-supported program completed in October 2015, IMF surveillance in Bangladesh de-intensified. Despite these developments, the World Bank was muted in voicing concerns with rising fiscal vulnerabilities in the latter part of the review period. Although most individual fiscal risks were identified and reconfirmed in the 2015 Public Expenditure Review update, the vulnerability associated with a compounding of risks—including those associated with the large buildup of implicit contingent liabilities and the understatement of NPLs—received little attention. In the context of the resumption of policy-based lending in 2018, the characterization of macroeconomic risks remained mostly benign, with the October 2019 MPO describing macroeconomic fundamentals as strong despite downside risks that included financial sector vulnerability, reform reversals, fiscal pressures, and a loss of competitiveness (Macro Poverty Outlooks 2017/18 Annual Spring Meetings; World Bank 2016–20).

The 2019 World Bank–IMF debt sustainability analysis concluded that Bangladesh was at a low overall risk for debt distress. It noted that “favorable debt dynamics” will keep public and publicly guaranteed external debt on a declining path (IDA and IMF 2019). However, this finding was based on a number of assumptions that include the following: (i) optimistic growth assumptions (the baseline projection assumes average annual real GDP growth of 7.3 percent over the long term, above the historical average of 6.5 percent a year); (ii) optimistic assumptions regarding export performance (for example, continued rapid growth of RMG exports) and remittance inflows; (iii) exclusion of implicit government guarantees (contingent liabilities of both financial and nonfinancial SOEs); and (iv) exclusion of several recent megaprojects financed with nonconcessional debt.4 There was also no mention of the previously identified potential for a systematic upward bias in GDP data.5

In contrast, Bangladesh’s growing financial sector risks were well documented. Vulnerabilities were concentrated in the banking sector, on which Bangladesh was reliant.6 The baseline financial sector assessment for the evaluation period was the 2010 Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP), jointly carried out by the World Bank and IMF and publicly released. The FSAP noted that the recovery rate of NPLs was low and constrained by lengthy legal processes. The overall banking sector faced a large and growing NPL problem despite strong economic growth. By March 2019, the NPL ratio had risen to 11.9 percent from 9.3 percent at the end of 2017. Policy decisions had undermined supervisory independence and obscured the accurate measurement of NPLs, which had led to a significant underestimation of problem assets.

World Bank MPOs for Bangladesh from spring 2016 to 2020 consistently and increasingly raised concerns about financial sector vulnerabilities (World Bank 2016–20). These concerns included mounting NPLs, which were described as a “major concern,” with the MPOs noting that the main factors holding back the recovery of defaulted loans were poor enforcement of laws and slow execution of decrees. The April 2019 MPO asserted that “risks to the outlook stem mainly from financial sector weaknesses and adverse private sector dynamics.”7 Heightened risk derived partly from policy changes that eroded bank supervisory independence and allowed defaulters to reschedule loans on easy terms. MPOs over this period regularly noted that financial sector weaknesses could derail investment and growth as weak governance in the banking sector limits lending capacity, diverts credit away from productive investment, and imposes large recapitalization costs.

Intra–World Bank Group Synergies

There was good coordination across Bank Group institutions during the evaluation period. The co-location of an IFC office in Dhaka fostered collaboration with the World Bank through regular sharing of information and complementary or joint work. This was not always the case when there was no IFC physical presence in Dhaka. The CPF envisaged that the World Bank and IFC would collaborate or undertake joint or complementary work, particularly in infrastructure (transport and energy) and private sector development. Complementary work in energy did materialize during the CPE period but not in transport. In the case of private sector development, IFC cofinanced the Private Sector Development Project through the Bangladesh Investment Climate Fund supported by the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development and provided implementation and technical support for the technical assistance and capacity-building component of the project. IFC advisory services provided inputs at preparation for three World Bank operations, including Export Competitiveness for Jobs and the Programmatic Jobs Development Policy Credits (DPCs 1–3). There was complementary work across three institutions in the energy sector, where IFC promoted private investment in five public-private partnership (PPP) operations and MIGA provided guarantees for five energy projects. IFC also provided financing for Bangladesh’s first liquefied natural gas import terminal to address the shortage of natural gas fuel supply for power generation.

Partnerships

Overall, the World Bank’s relationship with development partners was positive. Partnership was underpinned by a 2010 Joint Cooperation Strategy among bilateral and multilateral partners (including the World Bank) that was signed by the government of Bangladesh and 18 development partners. The World Bank effectively collaborated with development partners through several channels, notably through its long-standing engagement in the sectorwide approach (SWAP) in education (primary and secondary) and health. The World Bank’s collaboration with development partners in addressing the Rohingya displaced population crisis was also notable.

In education, the World Bank was a standing member of the Executive Committee of the Local Consultative Group, taking the rotating lead on several sector and thematic working groups. In primary education, the World Bank worked closely with the Asian Development Bank, the lead development partner, including through joint missions. It contributed by providing technical support in financial management, procurement, safeguards, and monitoring and evaluation, and it led and facilitated dialogue with the government and development partners in developing the secondary education SWAP.

As the lead development partner in the health SWAP, the World Bank provided fiduciary and technical oversight. Its leadership facilitated effective management of significant fiduciary risks through timely and quality technical support, helping improve the transparency of the procurement system and overall governance of the health sector (Implementation Completion and Results Report Review, Health Sector Development Program). Although the World Bank never served as chair or deputy of the Health Sector consortium, it led many aspects of the program, including implementation. The World Bank also contributed significant knowledge work to the SWAP (see chapter 3).

The World Bank coordinated with other UN agencies and development partners in responding to the Rohingya refugee crisis, including through joint advocacy on behalf of the displaced population and to ensure effective implementation of programs. The World Bank assigned a dedicated staff member whose terms of reference were to work with the government, the UN, nongovernmental organizations, and other agencies in the field. The relationship between the World Bank and the UN also supported the early-stage COVID-19 response in the host community and Rohingya population, including by raising awareness about how individuals and communities could protect themselves from the spread of the disease.

Although collaboration with the IMF was generally good throughout the period, collaboration on financial sector issues diminished somewhat during the decade. In mid-2018, World Bank staff requested IMF support to update the 2010 FSAP given marked changes in circumstances and significant growth in the banking sector. Under the agreed-on division of labor, the World Bank was able to conduct “development” modules for FSAP and the IMF conducted “stability” modules. IMF participation was therefore needed to address many of the obvious financial stability issues. However, given its own resource constraints and its prioritization of more systemically important countries, the IMF was not available to prepare an FSAP stability module at that time. The World Bank eventually decided to proceed with an FSAP development module in 2019, which was completed in 2020 (World Bank 2020b).

World Bank Group Program Delivery

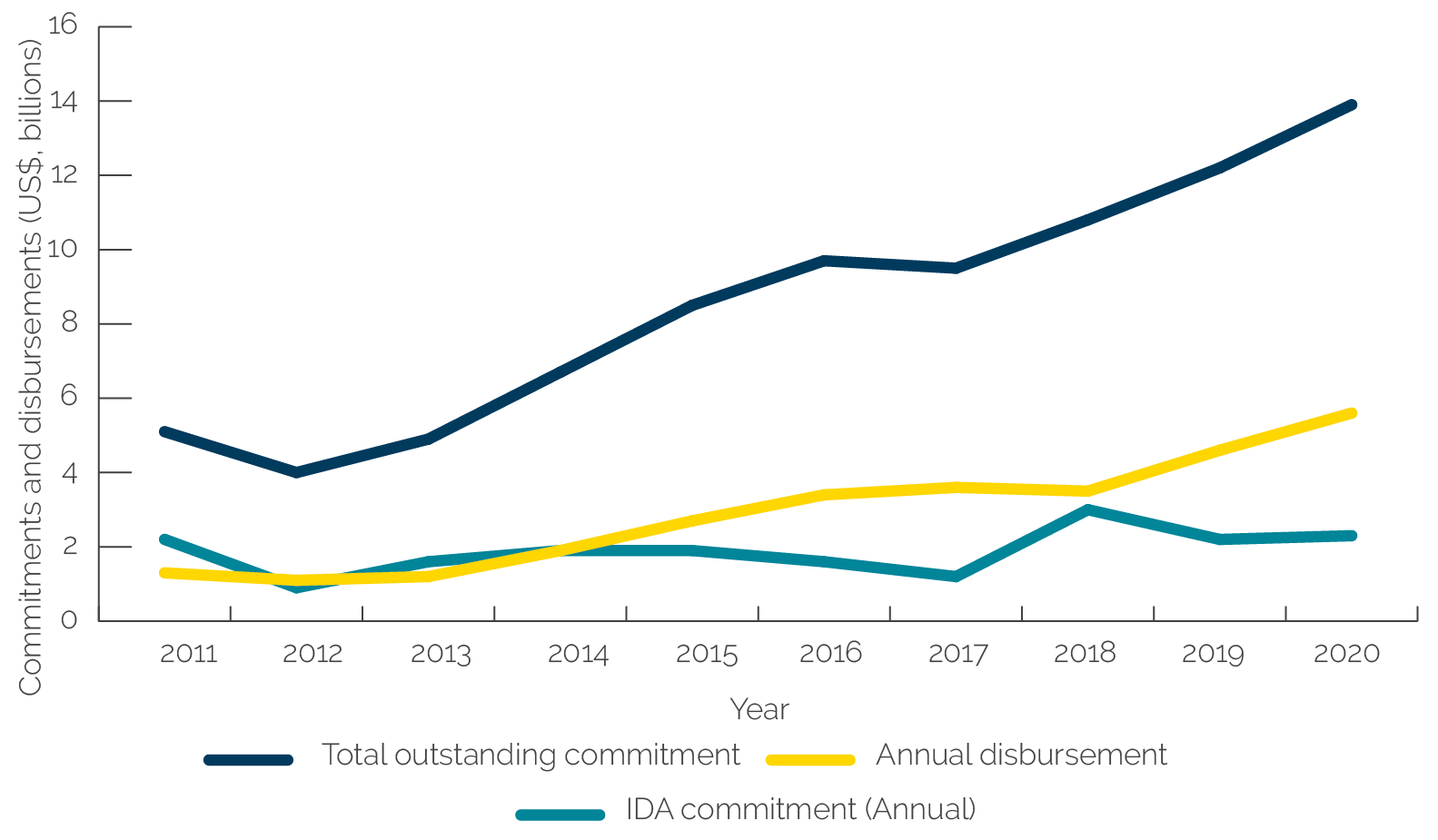

The Bank Group was the largest source of official development assistance to Bangladesh. Between 2011 and 2019, the Bank Group accounted for 60 percent ($6.7 billion) of total official development assistance flows ($11.2 billion) to Bangladesh. Total outstanding commitments at the end of the evaluation period were just under $14 billion (figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2. International Development Association Commitments and Disbursements in Bangladesh, Fiscal Years 2011–20

Source: Business Intelligence (database), World Bank, Washington, DC (as of July 20, 2021).

Note: IDA = International Development Association.

The World Bank approved 86 projects (including 23 additional financing) during the evaluation period, with total net commitments of $18.6 billion (table 2.1). This net commitment comprised 79 investment, 5 PforR, and 2 budget support operations. IFC financed 72 investments, with a total commitment of $1.6 billion, and MIGA had 6 guarantees, of which 5 were in the energy sector. Bangladesh also benefited from 40 trust-funded operations (for $887 million) from 17 sources. During the review period, transport accounted for the largest share of IDA commitments (15.8 percent), followed by education (14.2 percent) and social protection (13.8 percent; see appendix B for details). Two operations were halted due to government concerns.8

Table 2.1. Source and Value of World Bank Group Financial Support to Bangladesh, Fiscal Years 2011–20

|

Source of Financing |

Active Portfolio at the Start of Evaluation Period |

Commitments Approved During Evaluation Period |

Total |

|||

|

Projects (no.) |

Commitment (US$, millions) |

Projects (no.) |

Commitment (US$, millions) |

Projects (no.) |

Commitment (US$, millions) |

|

|

IDA |

26 |

2,539 |

86 |

18,585 |

112 |

21,124 |

|

Trust fund |

14 |

494 |

40 |

887 |

54 |

1,381 |

|

IFCa (net) |

3 |

24 |

72 |

1,584 |

75 |

1,608 |

|

MIGAb |

0 |

– |

6 |

976 |

6 |

976 |

Sources: Business Intelligence (database), World Bank, Washington, DC (as of December 30, 2020); Client Connection (December 30, 2020); Project Portal (database), International Finance Corporation, Washington, DC (as of December 30, 2020); and Project Portal (database), Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency as of December 30, 2020.

Note: IDA = International Development Association; IFC = International Finance Corporation; MIGA = Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency; – = not available.

a. Long-term investment commitments (excludes short-term finance).

b. Guarantees issued during 2013–20.

World Bank budget support resumed in 2018, but fiscal and financial sector issues received little attention among prior actions. A DPC was approved to support strengthening social protection and schemes for creating jobs for youth. As of the end of 2019, the authorities had not engaged the World Bank on fundamental fiscal reforms. However, recent work on a Country Economic Memorandum and a Public Expenditure Review may open the way for stronger policy dialogue and engagement on fiscal reforms.

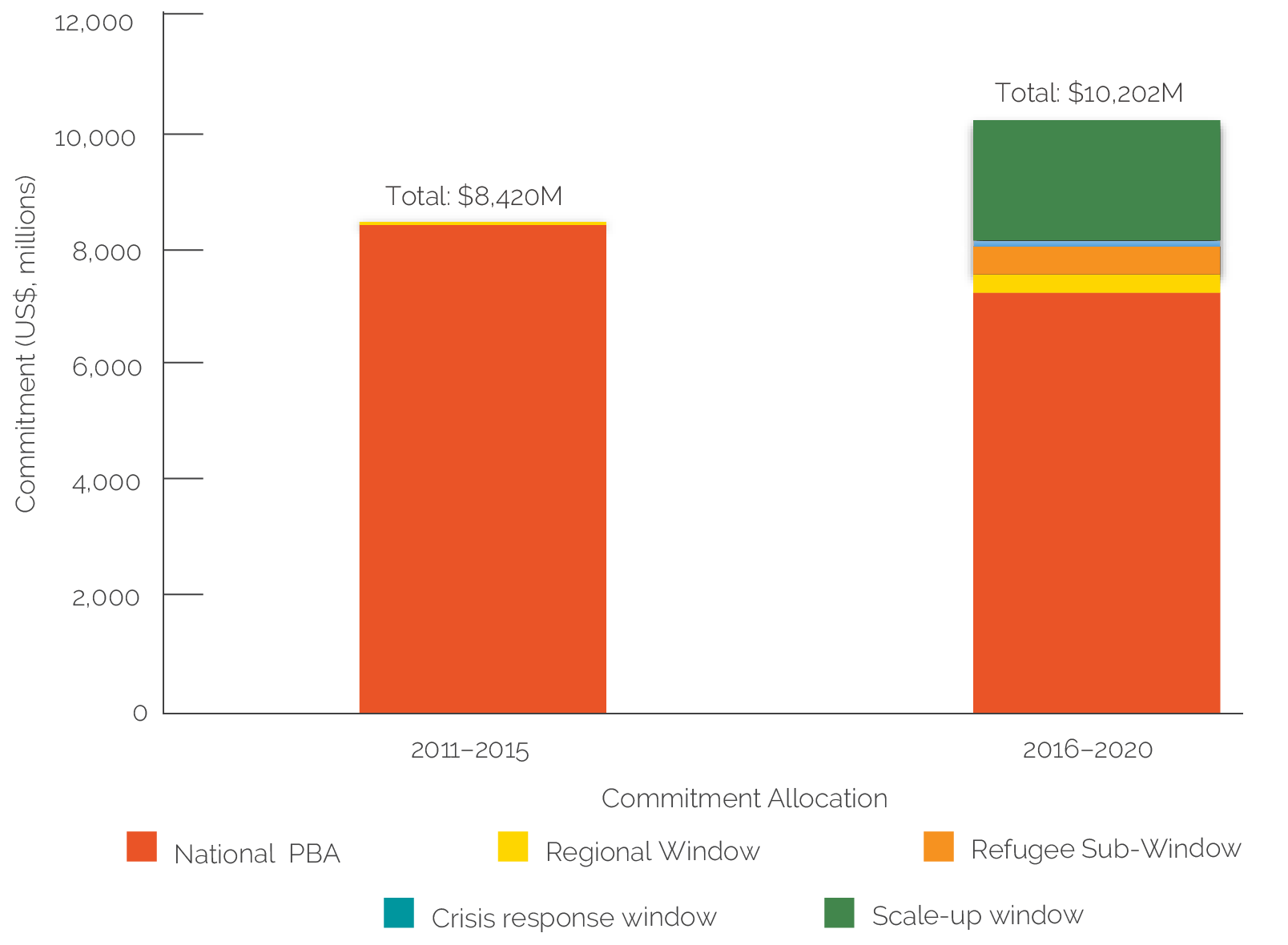

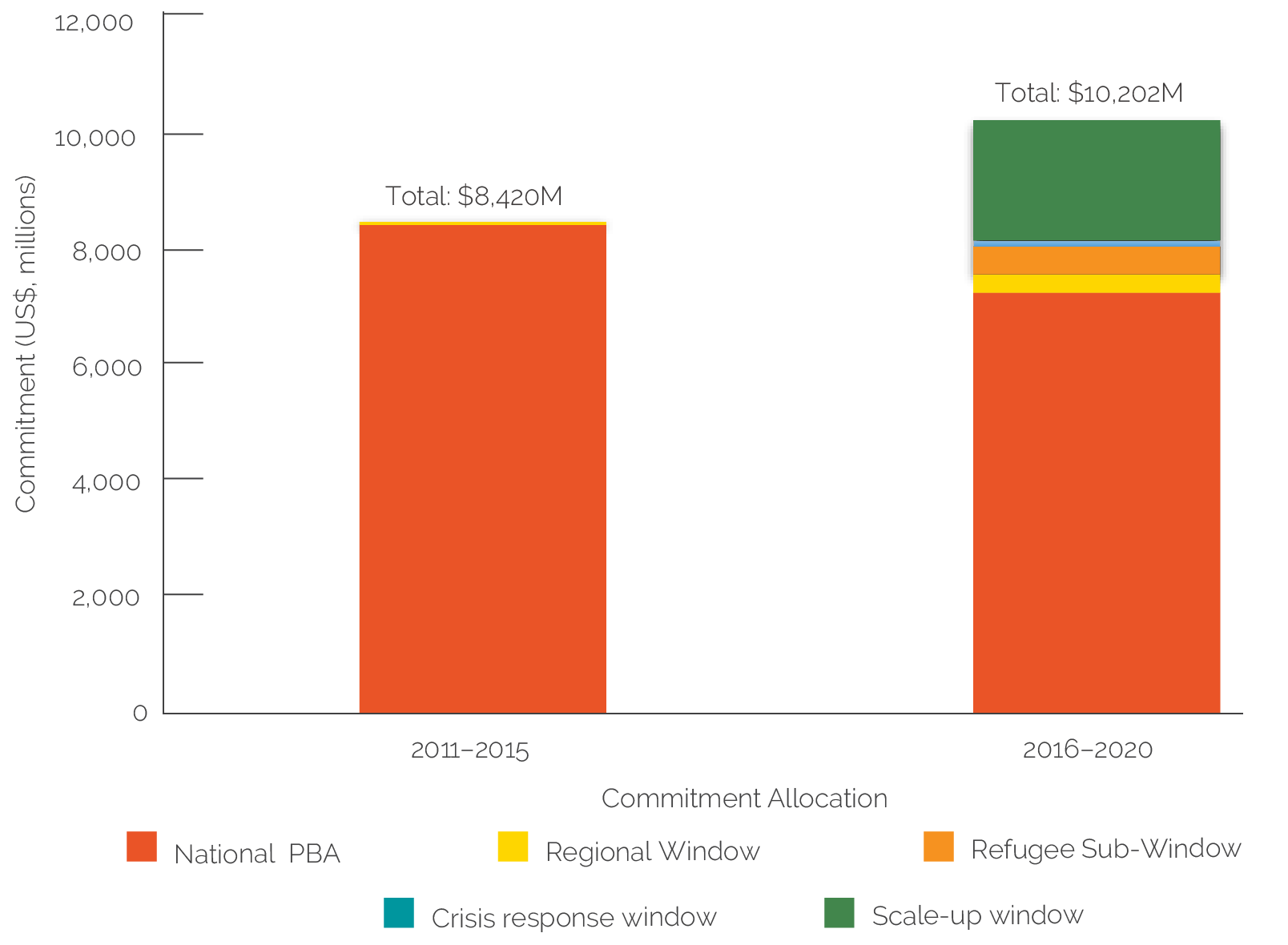

The IDA allocation for Bangladesh during the review period amounted to $18.6 billion, consisting of the national PBA and other IDA windows (refugee, regional, crisis response, and Scale-Up Facility). Although Bangladesh’s core PBA declined, due in part to a deteriorating CPIA rating in the second half of the review period,9 the total IDA allocation increased over the review period, from $8.4 billion to $10.2 billion. The decline in Bangladesh’s PBA was offset by an increase in funding, mostly from the Scale-Up Facility (figure 2.3).10

Figure 2.3. International Development Association Commitment Amount by Source, Fiscal Years 2011–20

Source: World Bank, IDA Resource Mobilization Department, Development Finance (DFi) database.

Note: CPE = Country Program Evaluation; FY = fiscal year; IDA = International Development Association; PBA = performance-based allocation.

The World Bank delivered 192 advisory services and analytics products, which concentrated on public administration, social protection, and the financial sector, while IFC delivered 42 advisory services. The World Bank’s advisory services and analytics (ASA) work consisted of several core diagnostics and analytical pieces, including the Poverty Assessment (2020), FSAP (2020), Country Environmental Analysis (2018), Jobs Diagnostic (2017), Diagnostic Trade Integration Study (2017), and several sector reviews on education, health, and social protection. No Debt Management Performance Assessment, Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability, or Public Investment Management Assessment was delivered. In terms of number of projects, IFC’s advisory services were mostly for financial institutions, followed by manufacturing, agribusiness, and services and PPPs.

Implementation and Results

Complex and ambitious project design combined with parallel project preparation and review process by the government contributed to implementation delays. Government processing of externally financed operations requires preparing a development project proposal before negotiations and having it approved by the Executive Committee of the National Economic Council, which is chaired by the prime minister. In particular, the government’s policy of prohibiting procurement and recruitment of key project management staff until after approval of the development project proposal by the Executive Committee of the National Economic Council has often been cited by World Bank staff and management as contributing to significant implementation delays. Capacity issues on the part of the government and delays in approval of large procurement packages (works and consultancy services) by the World Bank also contributed to delays, as did high turnover of government counterparts and task team leaders.

Despite the challenges of implementing projects in a capacity-constrained environment, overall performance was better than regional or World Bank–wide averages. The World Bank’s portfolio in Bangladesh saw a reduction in the share of problem projects starting in 2016.11 Before 2016, projects with ambitious design (for example, scope and outcome targets) were often restructured late in the project’s life and their closing dates extended, notwithstanding lack of progress. For example, the Central Bank Strengthening Project was ambitious in scope and restructured late. Its implementation was extended for another 5 years (for more than 10 years total). The Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) rated its outcome moderately unsatisfactory. Political instability also affected project implementation due to countrywide strikes after elections, which were particularly prolonged in 2014 and raised security concerns for Bank Group staff.

A reduction in the share of problem projects was achieved through early restructuring, including changes in project development objectives, results indicators, and, in some cases, partial cancellation of funds for nonperforming projects. Notwithstanding timely actions, implementation delays continued to occur due to procurement-related issues and delayed counterpart staffing. The location of a portfolio and country manager in the country office in Dhaka since 2016 has contributed to more focused attention on the portfolio.

Although there were shortcomings in results frameworks (see chapter 2, Program Design), project outcome ratings and subratings (Bank performance and M&E quality) compare favorably with the South Asia Region and World Bank averages (table 2.2; see appendix B for details).

Table 2.2. Project Outcome and Subratings: Bangladesh, South Asia, and World Bank, Fiscal Years 2011–20 (percent)

|

Ratings |

Bangladesh |

South Asia |

World Bank |

|

Outcome rating |

|||

|

Highly satisfactory |

22.1 |

4.8 |

3.0 |

|

Satisfactory |

45.3 |

36.5 |

35.0 |

|

Moderately satisfactory |

27.7 |

47.4 |

44.3 |

|

Bank performance |

91.5 |

88.6 |

84.6 |

|

M&E quality |

50.0 |

41.4 |

38.1 |

Source: Business Intelligence (database), World Bank, Washington, DC (as of February 8, 2022).

Note: Percentage of projects rated moderately satisfactory or above, averaged by commitment value. M&E = monitoring and evaluation

- The Padma Multipurpose Bridge Project was approved by the World Bank’s Board of Executive Directors in fiscal year (FY)2011 but was canceled before becoming effective because of allegations of corruption. The International Development Association was to finance the project for $1.2 billion, with cofinancing from the Asian Development Bank, the Japan International Cooperation Agency, and the Islamic Development Bank for $1.55 billion. The cancellation was documented in Moreno-Ocampo, Tong, and Alderman (2013) and World Bank (2013d, 2014b).

- The October 2018 World Bank Macro Poverty Outlook for Bangladesh noted that central bank autonomy (along with banking supervision) had been “substantially eroded,” and it assigned a “high priority” to “allowing the Bangladesh Bank to function independently, avoiding regulatory forbearance, and strengthening banking supervision” (World Bank 2016–20, 186).

- The Independent Evaluation Group’s recent evaluation Addressing Country-Level Fiscal and Financial Sector Vulnerabilities argues that these risks were consistently understated for Bangladesh starting in 2016 (World Bank 2021a).

- These include Padma Bridge ($3.65 billion), Seaport ($2 billion), Dhaka Metro Rail project ($2.5 billion), and Roopu Nuclear Power Plant ($11.4 billion).

- The accuracy of recent national accounts data that indicate an acceleration of growth from 6.5 percent a year between 2010 and 2015 to more than 8.3 percent per year has been questioned by several observers, including World Bank staff.

- Total bank assets represented about 60 percent of the country’s financial assets.

- Six state-owned commercial banks (and four private banks) failed to maintain the regulatory capital in Q2 2019, raising concerns about supervisory enforcement and independence. Stress testing by Bangladesh Bank indicates high sensitivity to the top large borrowers—the default of the top three large borrowers results in 21 banks falling below the minimum capital adequacy ratio.

- The River Management Improvement Program was negotiated but later dropped, and the Modernization of State-Owned Financial Institutions Project was approved but later canceled at the request of the government. The Performance and Learning Review noted that the projects were halted due to “lack of awareness and sensitivity to the client counterparts’ limitations and concerns” (World Bank 2020d, 12).

- Criteria for national performance-based allocation include Country Policy and Institutional Assessment rating, portfolio performance (as measured by percentage of problem projects), gross national income per capita, and population. The International Development Association (IDA) allocation is also influenced by the size of total IDA replenishments.

- Allocation of IDA subwindows is based on specific criteria for each subwindow. For instance, the Scale-Up Facility is provided based on criteria agreed to by the World Bank’s Operations Policy and Country Services and Development Finance (DFi) and uses International Bank for Reconstruction and Development terms (see https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/117811517713219394/pdf/IDA17-SUF-Retrospective-Board-paper-Final-Dec29-01042018.pdf) and are vetted at the regional level.

- The World Bank defines problem projects as projects that are rated unsatisfactory on progress toward achievement of the project development objective and/or the implementation progress in the Implementation Status and Results Report.