Using Qualitative Comparative Analysis to Explore Causal Links for Scaling Up Investments in Renewable Energy

6 | Application of Qualitative Comparative Analysis: Interpretation of Findings and Conclusions

Interpreting Findings

The QCA results provided insights based on the case study analysis into the factors that were critical to scaling up RE. These findings, triangulated with results from other methods, enabled conclusions to be drawn that are generalizable to other countries.

The QCA validated the ToC that was initially developed for the RE evaluation. It found potential causal links between the six originally identified barriers in the ToC and mobilizing investments in RE (figure 6.1). The same set of barriers were also independently identified as important obstacles to overcome by a global expert panel on RE (the Delphi panel; see figure B2.1.1 in box 2.1), which was convened by IEG for the RE evaluation. Together, the two methods affirmed the Bank Group’s attempts to help clients address all six of these barriers to different degrees through its investment portfolio. Successfully investing in RE capacity was also found to be near necessary and almost always sufficient for the realization of energy and environmental benefits. The example of Kenya confirmed that the environmental benefits are indeed contingent on RE displacing alternatives that are more polluting (that is, fossil-based generation), and that the causal relationship is weaker if the supplanted technologies are cleaner (that is, other renewables). This outlier finding further substantiated the causal relationships within the ToC. Since the QCA together with other methods fully validated the ToC illustrated in figure 3.1, further adjustments to the theory were not necessary in the case of the RE evaluation.

Figure 6.1. Barriers in the Theory of Change with Causal Link to Scaling Up Renewable Energy

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: RE = renewable energy.

Several countries mobilized investments in RE by adequately addressing all six barriers. The following five countries expanded RE by adequately addressing all of the identified major barriers: China, India, Mexico, Sri Lanka, and Turkey. Although the QCA did not find it strictly necessary to address all six barriers, the approach was identified to be sufficient given the potential causal relationship between each barrier and the expansion of RE capacity. This approach also highlighted the need for coordination among the primary institutions that make up the Bank Group (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, International Development Association, IFC, and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency). A portfolio review of RE interventions and country case studies undertaken as a part of the overall RE evaluation found the three institutions to have different comparative advantages helping clients address the various precondition barriers. The need for coordination would also extend to external development partners supporting similar complementary interventions, calling for closer partnerships.

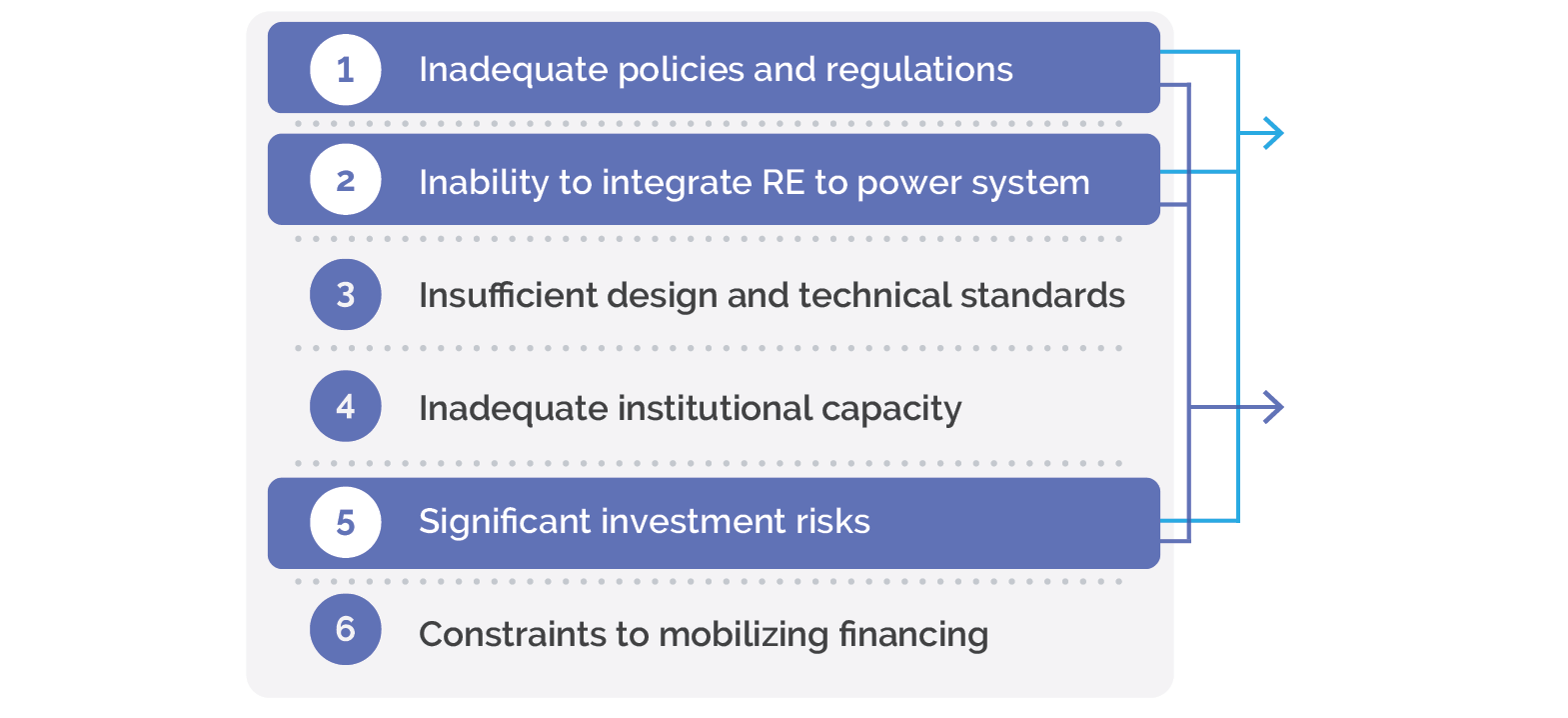

Improving policies and regulations and better integrating RE into power systems were identified as two near-necessary conditions for scaling up RE, presenting an additional causal pathway. The QCA results indicate that no country successfully scaled up RE without addressing these two critical precondition barriers (illustrated as 1 and 2 marked by the blue arrow in figure 6.2), implying they are priorities within the overall six. The global expert panel on RE convened by IEG for the RE evaluation also independently corroborated the importance of addressing inadequate policies and integrating RE into power systems by ranking them within the top three challenges facing a future scale-up in RE. In fact, Morocco and Nicaragua only adequately addressed these two essentials barriers yet managed to mobilize investments in RE by enhancing its investment climate for private participation, partly to develop concentrated solar power resources and wind, respectively. Sector analyses and assessment of the Bank Group portfolio indicate that the comparative advantage for addressing these two critical precondition barriers primarily rests with the public sector. The portfolio review also confirmed that the public sector arm of the group (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and International Development Association) was well positioned to provide extensive support to help clients address inadequate policies and regulations (a third of the 217 projects), although it had far less experience assisting with integration of RE into power systems (less than 7 percent of interventions in the portfolio).

The latter shortcoming was identified in the overall RE evaluation as a key emerging challenge for the institution, since the precondition barrier is expected to increase in importance because of greater penetration of variable RE in energy mixes as wind power and solar PV expand in client countries according to projections in the clean energy transition. Thus, it can be concluded that the two precondition barriers are priority areas to address, and, in some cases, successfully reforming them may be sufficient by themselves, at least for initial and immediate scale-up of RE.

Figure 6.2. Two Additional Alternative Pathways for Scaling Up Renewable Energy

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: RE = renewable energy.

The QCA identified a third pathway to scaling up RE, especially through private participation, by taking additional action to mitigate any residual risks when policy and regulatory shortcomings and integration of RE into power systems are also adequately addressed simultaneously. Jordan and Morocco (in the change or delta scenario), which mobilized private participation in developing its RE resources, combined efforts to reform its policy framework and facilitate grid integration with additional measures to mitigate residual risks (illustrated as 1, 2, 5 marked by the green arrow in figure 6.2). For example, the World Bank helped Jordan publicly assess its solar and wind resources (to mitigate RE resource risks), which helped mobilize private investors and develop markets for both technologies; IFC assisted with standardizing project documentation to create a common platform for investing in solar PV, which facilitated the development of seven 10–20 megawatt projects. In Morocco, the World Bank funded a standby facility to ensure continued payments by the offtaker for purchases of electricity generated from concentrated solar power, providing assurances to the private developer against commercial and market risks. The RE evaluation found the Bank Group is well placed to mitigate investment risks, since it can mobilize multiple instruments through its three primary institutions—World Bank (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and International Development Association), IFC, and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency. This specific third pathway identified by the QCA was recently independently highlighted by the International Energy Agency as “the three main challenges” that need to be addressed to “accelerate significantly” RE growth for meeting the long-term goals established under the SDGs and the Paris Agreement.

“Renewable electricity growth still needs to accelerate significantly to meet long-term sustainable energy goals. This growth is possible if governments address the three main challenges to faster deployment: policy and regulatory uncertainty; high investment risks in many developing economies; and system integration of wind and solar PV in some countries.”

Source: IEA 2019.

Conclusion

The application of QCA proved to be useful in triangulating findings with other methods within the broader RE evaluation, helping to draw conclusions related to scaling up RE and meeting global goals established by the international community. In addition to helping validate the ToC underlying the entire evaluation, the QCA also helped identify three specific pathways through which precondition barriers could be addressed to overcome challenges facing the successful achievement of the clean energy transition. Addressing all six precondition barriers was one such pathway, given that they were all found to have a potential causal link to mobilizing investments in RE. A second specific pathway was to address inadequate policies and regulations and grid integration challenges—two precondition barriers that were near necessary in all pathways. A third pathway was to simultaneously address the two near-necessary precondition barriers together with mitigating residual risks—a particularly useful approach for mobilizing private investments in RE.

Two preconditions are shared by all three pathways. Improvements to the policy and regulatory environment appear to be a necessary condition, as discussed above. Successful integration of RE into electrical power systems emerges as a core condition across all three pathways, indicating that overcoming this barrier is essential to improving RE capacity. Addressing this barrier, however, is not sufficient by itself, since all pathways also include the reduction of at least one other barrier. The successful improvement of the policy and regulatory environment emerges as a common condition across all three pathways, reflecting its status as a necessary condition.

Although the inclusion of QCA added value to the overall RE evaluation, as with all methodologies it should be applied with rigor, awareness of its limitations, and recognition of the real-world trade-offs that need to be made in its design and application. Several of these limitations are listed here. First, since QCA relies on the strength of underlying theory and the quality and depth of evidence, and is susceptible to varying sample diversity, size, or both, subject matter specialists were needed for developing the ToC, preparing in-depth country cases, and helping contextualize and interpret the results. Second, it was equally important to have methods experts familiar with QCA to help with experiment design, running the model, and interpreting the results. Third, it was also important to select an adequately representative group of countries within the available budget, ensuring sufficient variation within the sample for key areas of scrutiny.

Fourth, another potential limitation involves the reliability and consistency of scoring across participants. Although the team met with a case study specialist to ensure that case assessments were correctly calibrated, the use of intercoder reliability testing (in particular, the blind testing of country scores) would have provided a more objective analysis of the scores. This in turn would have provided additional insights on the range and convergence of results relative to each country case study. Although panel discussions on the results may have reached the same conclusions, they are not immune from the various intergroup dynamics that might inadvertently introduce confirmation bias or satisficing. Finally, the analysis would also have benefited from a more nuanced discussion of the timing of reforms, since all three of the discussed pathways are likely to shift at different rates over time.

Taken together, findings from the QCA provided vital corroboration of evidence from other methodological approaches used in the evaluation of RE investments. Taken alongside a structured literature review, semistructured interviews, a Delphi-moderated expert panel, and the review of the Bank Group’s over 500 investment projects, the approach offered a disciplined and collaborative approach to ensure consistency across case studies. The QCA method provided a means of accurately translating qualitative judgments into quantitative information used in the analysis. It helped overcome other traded-off design features such as multicoder reliability tests, which time and budget did not allow for in this particular case. Ultimately, the robustness of the results and the added value provided in triangulating among various evidence streams made the QCA method a valuable analytical tool for evaluative synthesis.