Enhancing the Effectiveness of the World Bank’s Global Footprint

Chapter 2 | Trends

The World Bank Group has undertaken decentralization reforms since 1997 and gradually adjusted its global footprint to meet corporate commitments to low-income countries and the fragile and conflict-affected situation agenda.

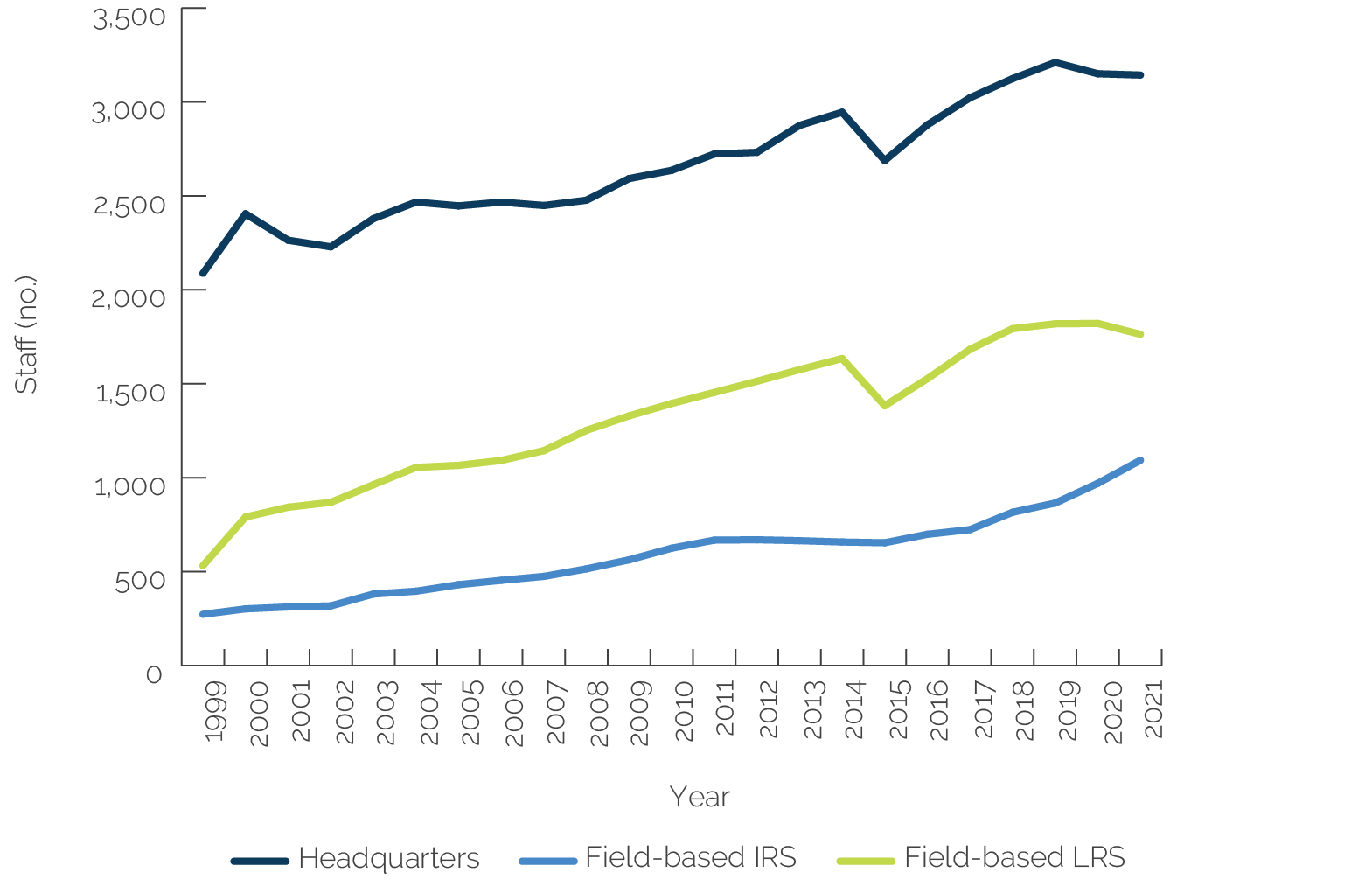

The World Bank has tripled its staff presence in the field since 1999 but increased its staff presence in headquarters only by about half in the same period. This expansion of the global footprint was driven by the hiring of locally recruited staff to country offices. Locally recruited staff now make up the largest share of the World Bank’s field staff presence.

The World Bank’s decentralization of project-level decision-making (accountability and decision-making task team leaders) has been less robust than anticipated. Only about a third of the projects managed in the field are led from the projects’ recipient countries. The share of projects managed from recipient countries is even lower in fragile and conflict-affected situation countries.

Recent adjustments to the World Bank’s operational model bring risks and opportunities to the current decentralization model.

The purpose of this chapter is to review the evolution and trends of the World Bank’s decentralization efforts since they began more than two decades ago.1 The chapter sets the organizational context of decentralization, which is critical for answering the evaluation questions, and contributes to evaluation question 2 by exploring the nature and level of the staffing and decision-making authority in the field (gray box in figure 1.1). The chapter first examines the World Bank’s decentralization model and how the World Bank adjusted and readjusted this model. It then looks at the trends in staff deconcentration and decision-making devolution and shares some relevant lessons from IFC’s decentralization experience.

Reforms

The Bank Group began its decentralization efforts in 1997 with the Strategic Compact, and by 2008, most country directors and many sector and fiduciary staff had already moved to the field. The Strategic Compact articulated several reasons for decentralizing the World Bank.2 These included making the World Bank more responsive to clients, strengthening the World Bank’s in-country partnerships, better integrating global and country knowledge inside the organization, bolstering client ownership over national development processes, and increasing the cost-effectiveness of the World Bank’s support to client countries (World Bank 2001). By 2008, these decentralization efforts were well established, with many sector and fiduciary staff having already moved to the field and 75 percent of country directors being relocated to country offices, compared with just 5 percent in 1997 (World Bank 2008, 2010a, 2011).

However, as time passed, the inefficiencies and gaps in the decentralization model became pronounced. First, the financial costs of decentralization increased significantly, driven by rising staff salaries, field assignment benefits, additional infrastructure to accommodate field staff, and security costs to keep field staff safe, especially in FCS countries. Second, decision-making remained mostly centralized in headquarters, limiting the benefits of decentralization. Third, the model, as applied through the World Bank’s matrix system, hampered staff’s mobility across Regions and central units and impeded the flow of global knowledge (World Bank 2008, 2009).

From 2008 to 2012, World Bank management made incremental changes to the decentralization model to remedy some of these inefficiencies. First, World Bank management abandoned its centralized approach to field staffing, and each Region proposed its own strategy for where to place sector staff. Second, to reduce reliance on Washington, DC, as the only global headquarters and bring decision-making closer to clients, the World Bank elevated a few country offices—such as those in Kenya, Senegal, and South Africa—to Regional or subregional hubs with more sector and operational support staff, including those in financial management and procurement units, and more managers. In a similar adjustment, the World Bank also deployed more sector staff to Country Management Units (CMUs), or countries hosting country directors (CD countries), which act as minihubs to clusters of country offices.

The 2013 World Bank reorganization shifted managerial decision-making to the GPs, which also affected the decentralization of staff and decision-making.3 More specifically, the management of operational budgets moved to GPs, and operational staff and practice managers reported to directors in the GPs rather than to sector directors in the Regions. The purpose of this change was to reduce the Regional silos and limited knowledge flow under the World Bank’s previous matrix model. Past Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) evaluations and the World Bank’s own corporate-level monitoring during FY15–17 demonstrated that the reorganization increased cross-support and mobility across Regions (World Bank 2017a, 2019b). However, as this chapter will show, the reorganization also slowed the World Bank’s decentralization of staff and decision-making by moving many sector staff back to headquarters to sit closer to their GP and significantly weakening the influence of country directors.4 Moreover, this new model lacked adequate mechanisms to work across GPs and among GPs and CMUs (World Bank 2019b).

In 2019, the World Bank adjusted its organizational model once more, shifting operational decision-making back to the Regions. According to a senior management communication in April 2019, this adjustment to the operational model “preserves the benefits of the GP structure while strengthening links and cooperation between GPs and Regions” (World Bank 2019c). These adjustments also reinstated the regional director position, handing control over operational budgets and sector staff back to the Regions. This latest change in the model may bring back some features of the World Bank’s previous matrix structure that led to the reduced mobility of sector staff across Regions and may pose risks to the flow of global knowledge.

In 2020, the World Bank, motivated by the 2018 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development capital increase package and IDA commitments, made efforts to expand its global footprint again. The expansion broadly aims to serve clients better, especially in LICs and LMICs and in countries affected by FCV. Key elements of this expansion include placing more sector staff and practice managers in the field and completing the placement of all country directors in the field. More specifically, the World Bank announced new corporate targets to increase the proportion of staff in the field from 45 percent to 55 percent by the mid-2020s, place half of all practice managers in the field by FY22, ensure that one in three field-based practice managers are located in Africa, and move project task management to the field. The World Bank justified these targets in a 2019 management statement, explaining, “While it is challenging to determine an ‘optimal’ level of decentralization, having over half of our staff in the field demonstrates our commitment to moving our work closer to our clients” (World Bank 2019a).

IFC tried to maintain the quality and common standards of a centralized model during its decentralization, while increasing the empowerment, risk taking, and innovation of a decentralized model. Lessons from IFC’s experience in decentralization are useful for understanding the possible gains and trade-offs for the World Bank, should it take a similar pathway. Starting in 2009, IFC delegated its decision-making authority for investments to senior managers in the field, leaving only industry or sector specialists at headquarters. This made it easier for IFC to interact and respond to clients, since staff no longer had to wait for approvals from headquarters. But IFC’s decentralization also led to concerns about IFC Regions operating in silos and taking greater risks than headquarters would have taken. These concerns led to a reform in 2018 that shifted some of IFC’s decision-making back toward headquarters to ensure quality and consistency across Regions. It may still be too early to assess the impacts of IFC’s 2018 accountability and decision-making (ADM) reform, but IFC managers interviewed for this evaluation identified some pitfalls from the reform. First, the reforms diluted accountability because of more people getting involved in decision-making. Second, investment processing takes longer. And third, staff feel less empowered and less able to give quick and straight answers to clients. The underlying cause seems to be that the distance of global directors from the field leads to more transactional costs, since everything done in the field has to be checked at headquarters.

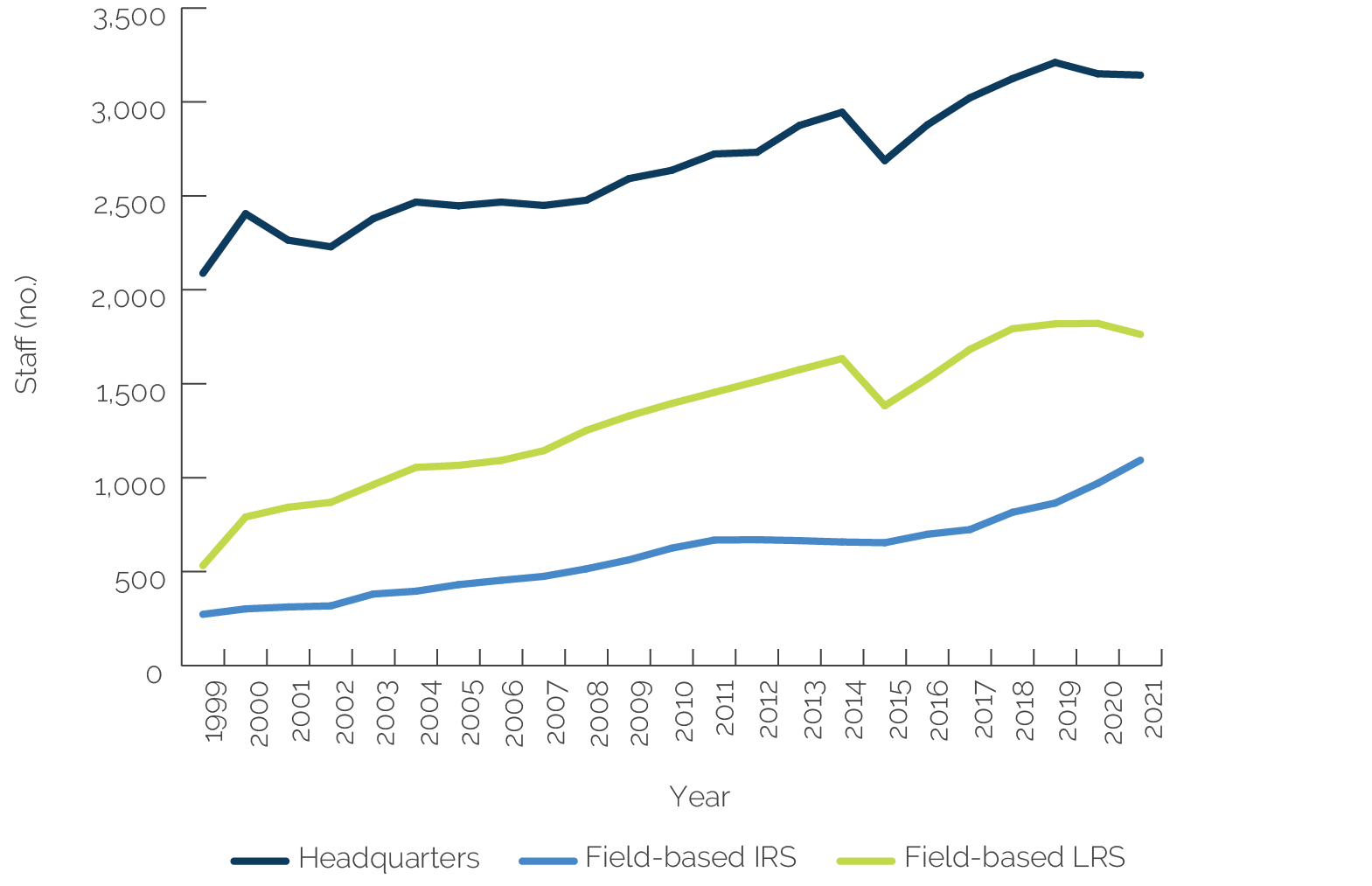

Deconcentration of World Bank Staff

Since 1999, the World Bank increased its field presence by more than three times, and its headquarters presence increased by about half. As a result, the balance of staff between headquarters and the field also shifted. In 1999, during the Strategic Compact’s implementation, 28 percent of all World Bank staff were posted in the field.5 Twenty-two years later, this share has increased to 47.6 percent, and the share of staff in headquarters has declined from 72 percent to 52.4 percent with a 2 percent increase in field staff only in the past two fiscal years (figure 2.1). The expansion of the World Bank’s global footprint during those first years of decentralization was driven largely by the hiring of local staff, not by hiring more international staff, who continued to rotate among headquarters and country offices (figure 2.1). Subsequently, by 2021, locally recruited staff (LRS) made up the biggest share of the World Bank’s field-based staff.

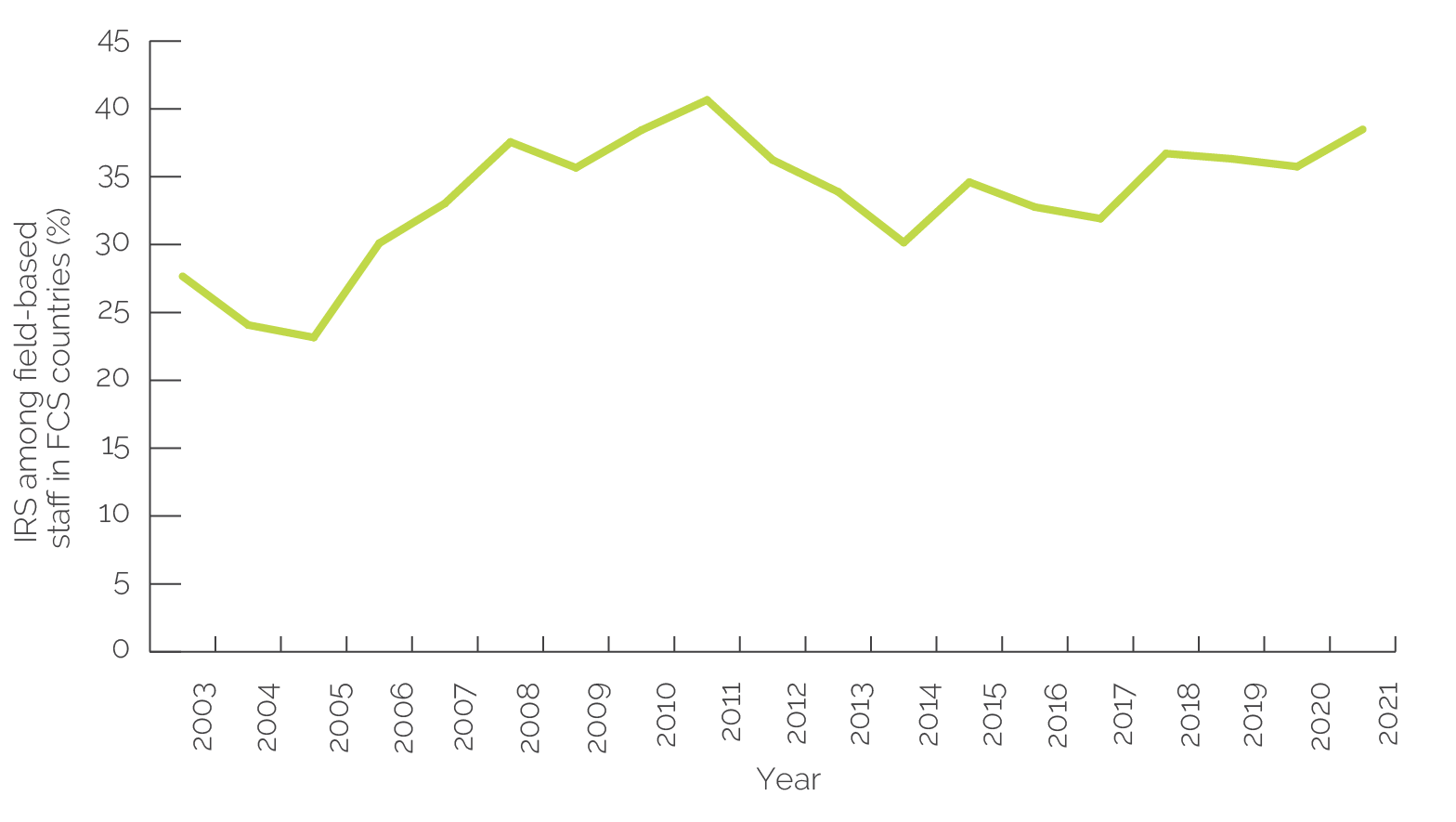

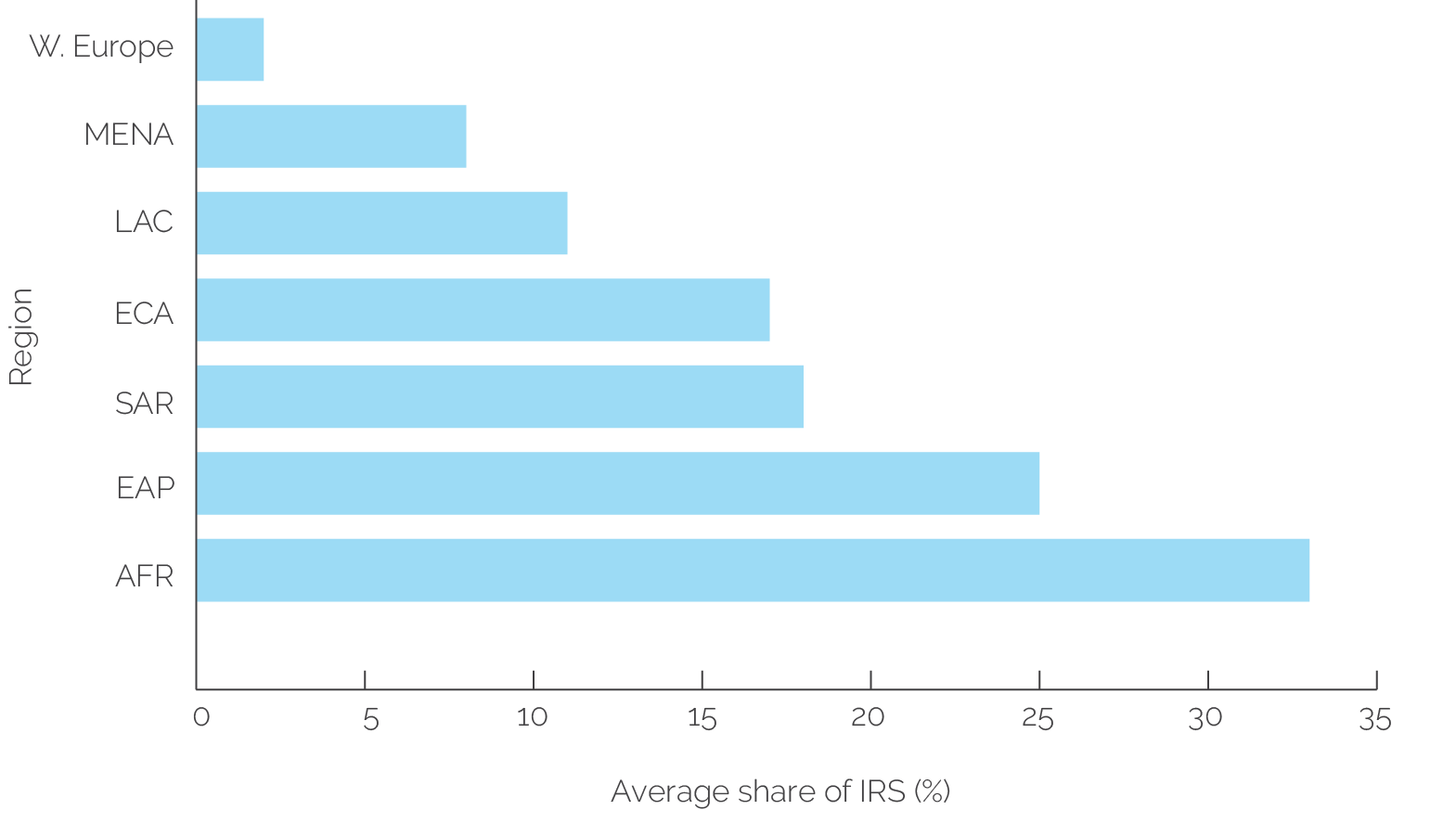

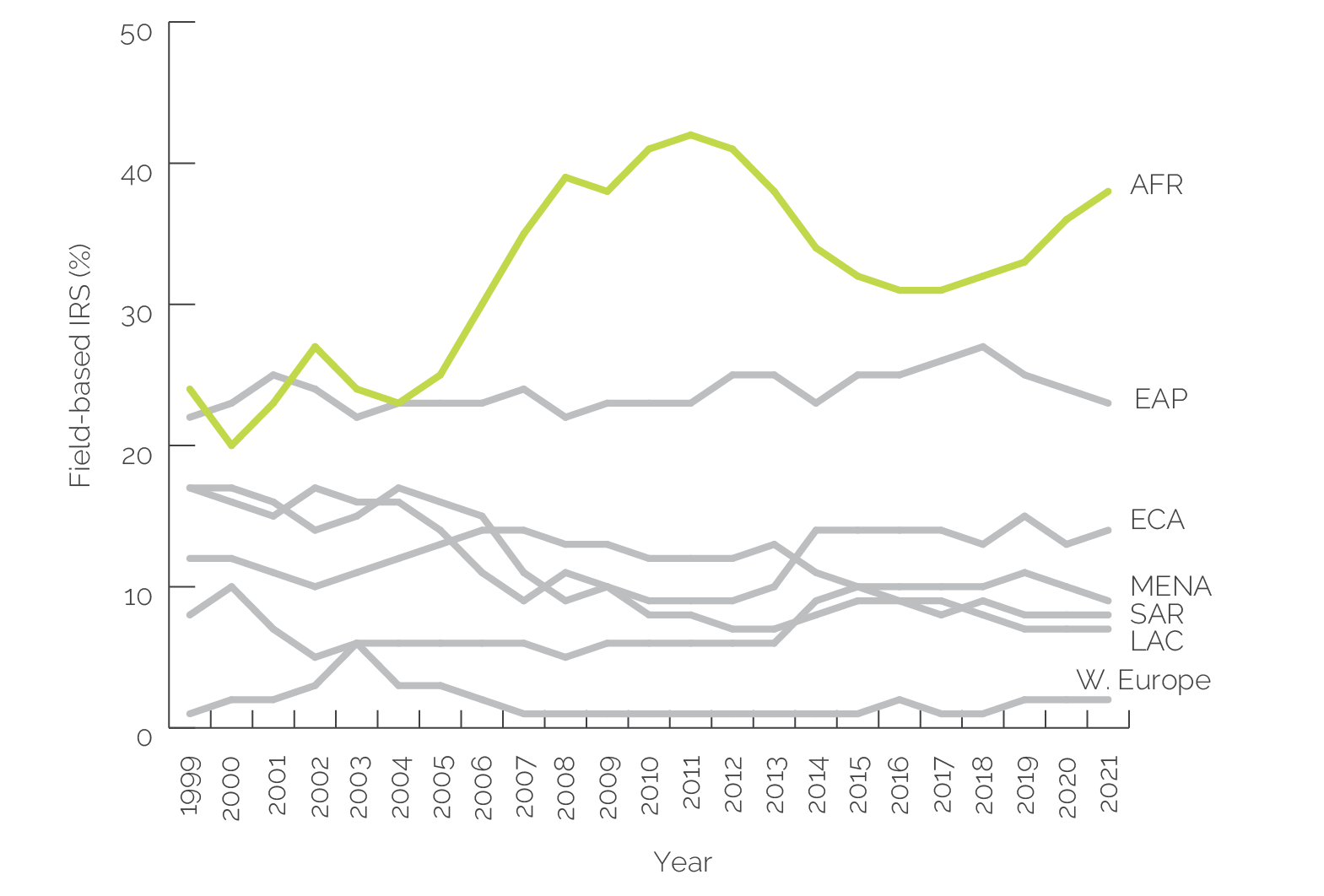

The World Bank expanded its global footprint to meet its corporate commitments to the FCS agenda and to LICs. The World Bank’s continuous commitment to IDA countries and enhanced commitment to the FCS agenda since the 15th Replenishment of IDA in 2007 dictated the flow of staff to LICs in all World Bank Regions.6 LICs and LMICs had the largest share of field-based staff from FY99 to FY21, which is understandable because these countries make up the largest share of client countries. The Africa Region, which has more FCS and LICs than any other Region, employed about one-third of all field-based professional World Bank staff from FY99 to FY21 and the largest share of IRS (figures 2.2–2.4). In FCS countries globally, staff increased about two and half times since 2003.7 From 2006 onward, at least one-third of all field-based staff in FCS countries were IRS, on average. In 2011, the World Bank had the highest share of IRS (41 percent) located in FCS countries (figure 2.4).8 Since 2019, the share of IRS in FCS countries increased by nearly 2 percent.

Figure 2.1. World Bank Staffing Trends, Fiscal Years 1999–2021

Source: World Bank human resources data.

Note: Includes only professional staff in operations, grade level GE+. Excludes extended-term consultancy contract holders. IRS = internationally recruited staff; LRS = locally recruited staff.

Figure 2.2. Field-Based Internationally Recruited Staff by Region, as a Share of All Field-Based Staff, Fiscal Years 1999–2021

Source: World Bank human resources data.

Note: Includes only professional staff in operations, grade level GE+. Excludes extended-term consultancy contract holders. Excludes staff from institutional, governance, and administrative units. AFR = Africa; EAP = East Asia and Pacific; ECA = Europe and Central Asia; IRS = internationally recruited staff; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; MENA = Middle East and North Africa; SAR = South Asia; W = Western.

Figure 2.3. Field-Based Internationally Recruited Staff by Region, Annual Trend, Fiscal Years 1999–2021

Source: World Bank human resources data.

Note: Field-based staff with region identified as HQ or missing are excluded. AFR = Africa; EAP = East Asia and Pacific; ECA = Europe and Central Asia; HQ = headquarters; IRS = internationally recruited staff; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; MENA = Middle East and North Africa; SAR = South Asia; W = Western.

Locally and internationally recruited professional staff play complementary roles in the field. There is a recurring debate within the World Bank about whether to rely heavily on international staff in the field or use more local staff. Placing IRS in the field has significantly higher costs, especially in FCS countries. Local and international staff, however, bring distinct strengths and play complementary, reinforcing roles in the field. For example, international staff usually start their careers in headquarters, so they carry on the World Bank’s corporate culture, bringing global technical knowledge.9 The competitive advantage of local professional staff is that they bring language skills, long-standing and trusting relationships with government counterparts, continuity and institutional memory to country programs, and a deep understanding of the country’s local context.

The World Bank hires third-country nationals (TCNs) to increase the technical and operational capacity in country offices. The World Bank introduced TCNs as a hiring mechanism in 2014, and they have been particularly popular in FCS countries where there are often fewer IRS and a scarcity of skilled LRS. From 2014 to 2020, the World Bank hired 559 TCNs, mostly in the Africa Region. Most TCNs have previous World Bank experience and were hired from headquarters or World Bank country offices. Although this number of TCNs is very small compared with the number of LRS and IRS, the number of TCNs is currently growing. This is similar to IFC’s staffing, which relies primarily on TCNs for its field presence. TCN staff can bring cross-country knowledge; however, they are also less likely to be exposed to the World Bank’s culture and corporate vision and, in the longer term, would likely experience similar difficulties as local staff, as described in chapter 4.10

Figure 2.4. Internationally Recruited Staff Located in FCS Countries, Fiscal Years 2003–21

Source: World Bank human resources data.

Note: FCS = fragile and conflict-affected situation; IRS = internationally recruited staff.

Devolution of Decision-Making

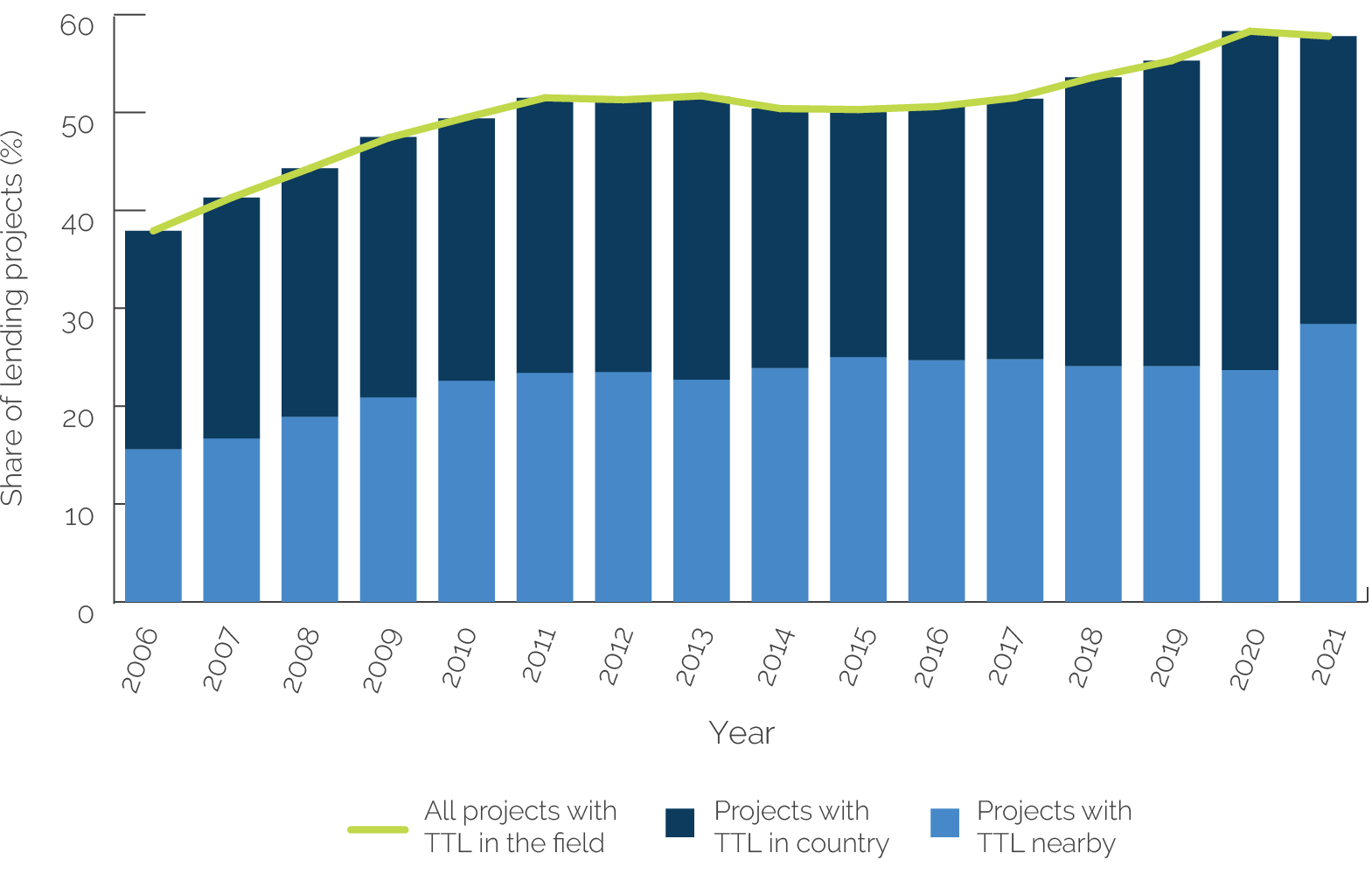

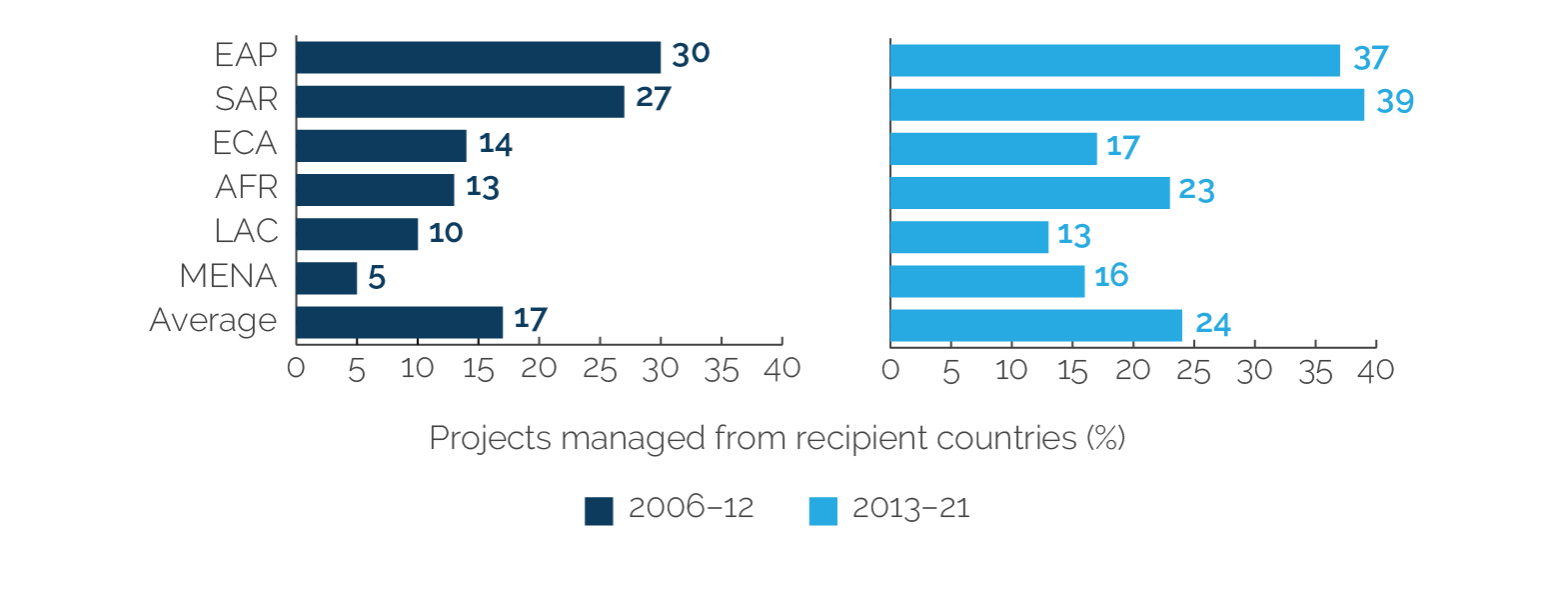

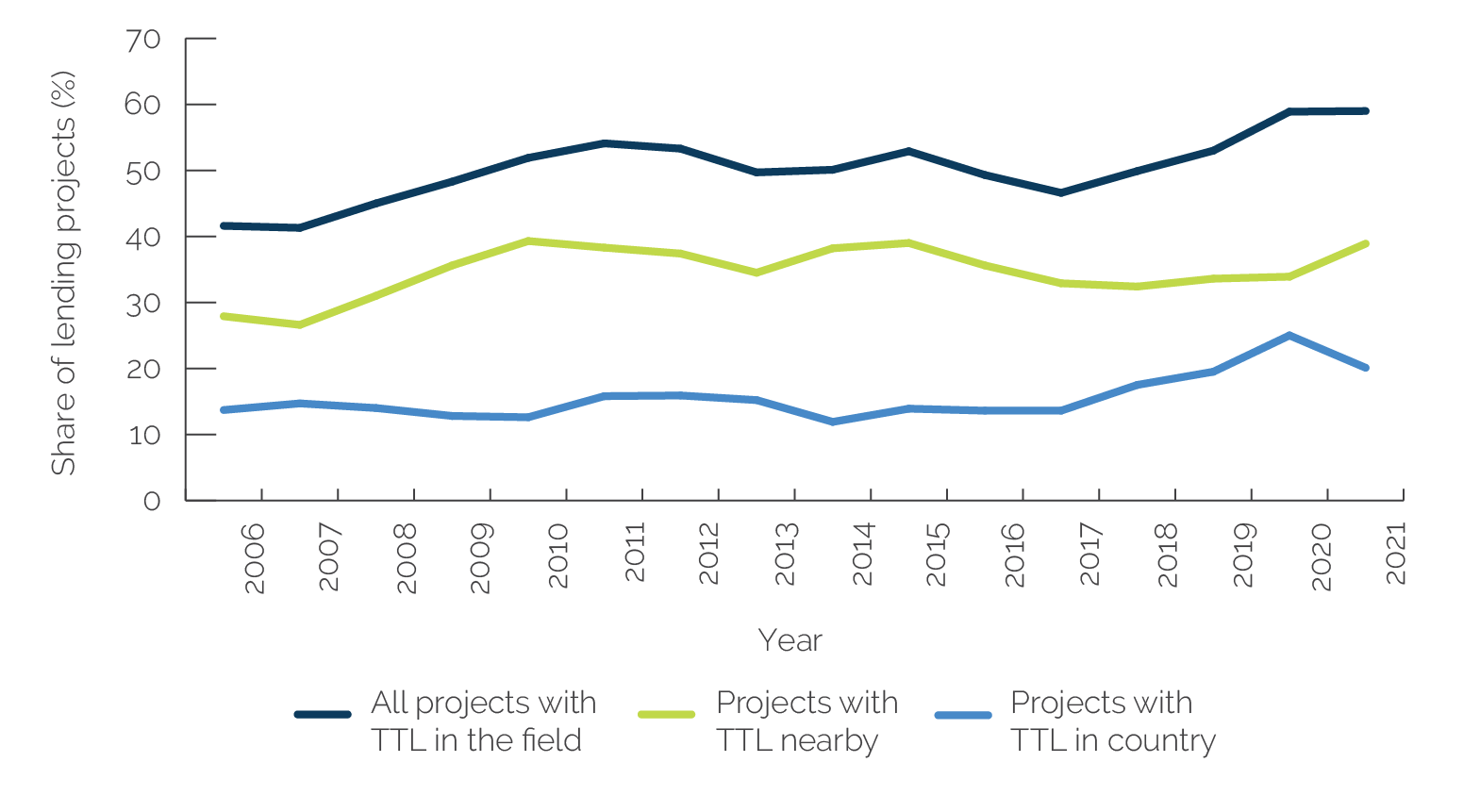

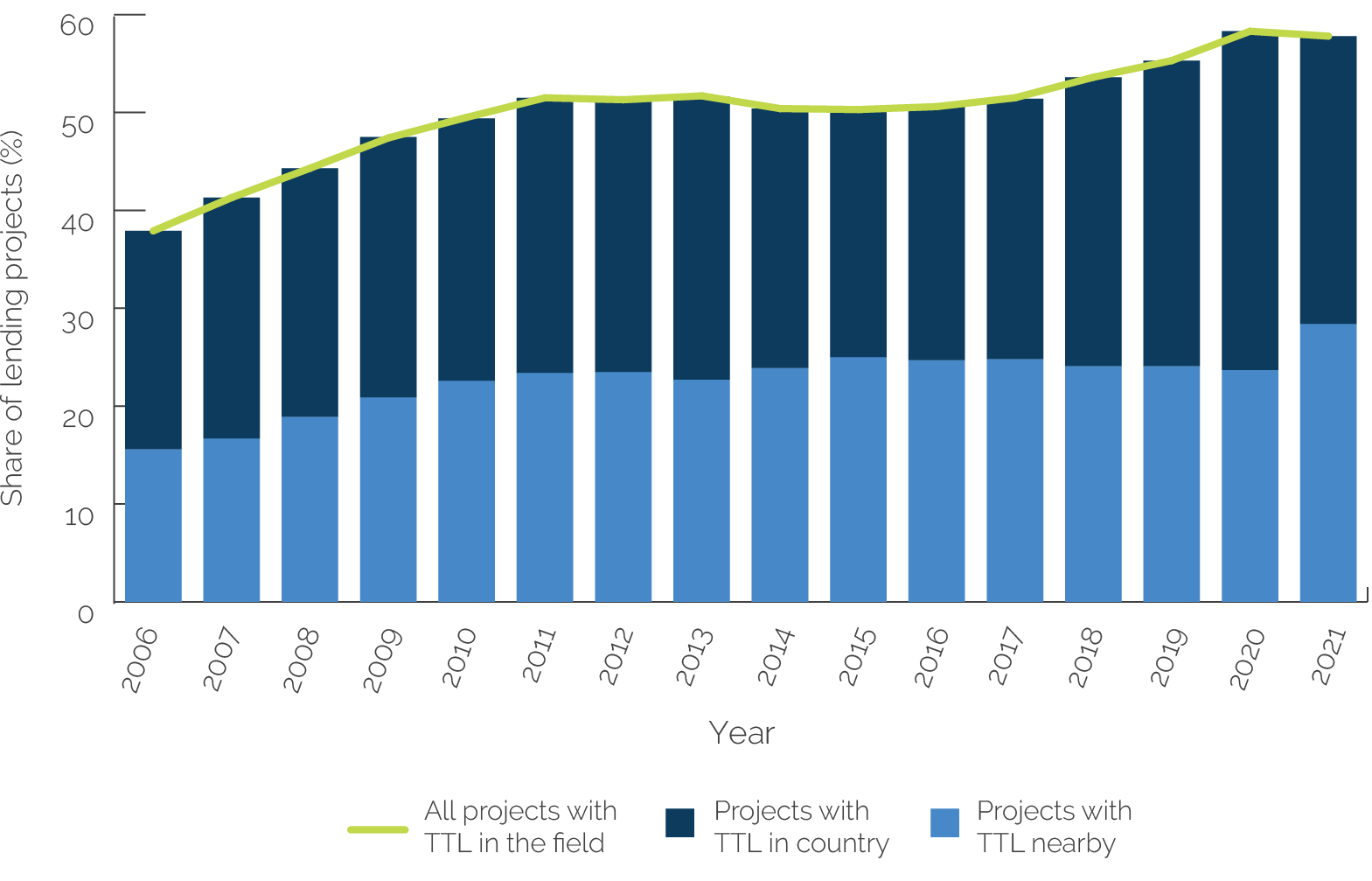

Project-level decision-making has increasingly moved to the project’s recipient country, but this shift has been slow.11 On average in FY06–21, 50 percent of all lending projects were managed, that is, had the ADM-responsible TTL (TTL with decision-making power), in the field,12 and of these, 28 percent were managed from project recipient countries (figure 2.5). All Regions have increased their shares of lending projects led from recipient countries during FY13–21 period, with Europe and Central Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean having the smallest increases (figure 2.6). Being farther from headquarters, the East Asia and Pacific and South Asia Regions have the largest share of projects led from recipient countries.

Figure 2.5. Lending Projects Managed from the Field, Fiscal Years 2006–21

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis of human resources and project portfolio data.

Note: “TTL in country” means the TTL is in the project recipient country; “TTL nearby” means the TTL is not in the project recipient country but somewhere in the same Region. TTL = task team leader.

The World Bank has also delegated more country-focused advisory services and analytics (ASA) tasks to TTLs in recipient countries.13The World Bank has historically managed ASAs from headquarters. This is likely because headquarters has more technical or sector staff and easier access to knowledge-related funding opportunities, like trust funds. For example, during 2006–12, more than 70 percent of country-focused ASAs were produced in Washington, DC, for all Regions except East Asia and Pacific. This has changed dramatically in all Regions since 2013, with East Asia and Pacific and South Asia experiencing the largest increase in ASAs managed from recipient countries. Currently, East Asia and Pacific manages nearly 60 percent of country-focused ASAs from the field. Meanwhile, similar to its lending portfolio, Latin America and the Caribbean manages the fewest ASAs from the Region, again likely because of Latin America and the Caribbean’s proximity to headquarters.

Figure 2.6. Lending Projects Managed from Recipient Countries, by Region

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis of human resources and project portfolio data.

Note: AFR = Africa; EAP = East Asia and Pacific; ECA = Europe and Central Asia; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; MENA = Middle East and North Africa; SAR = South Asia.

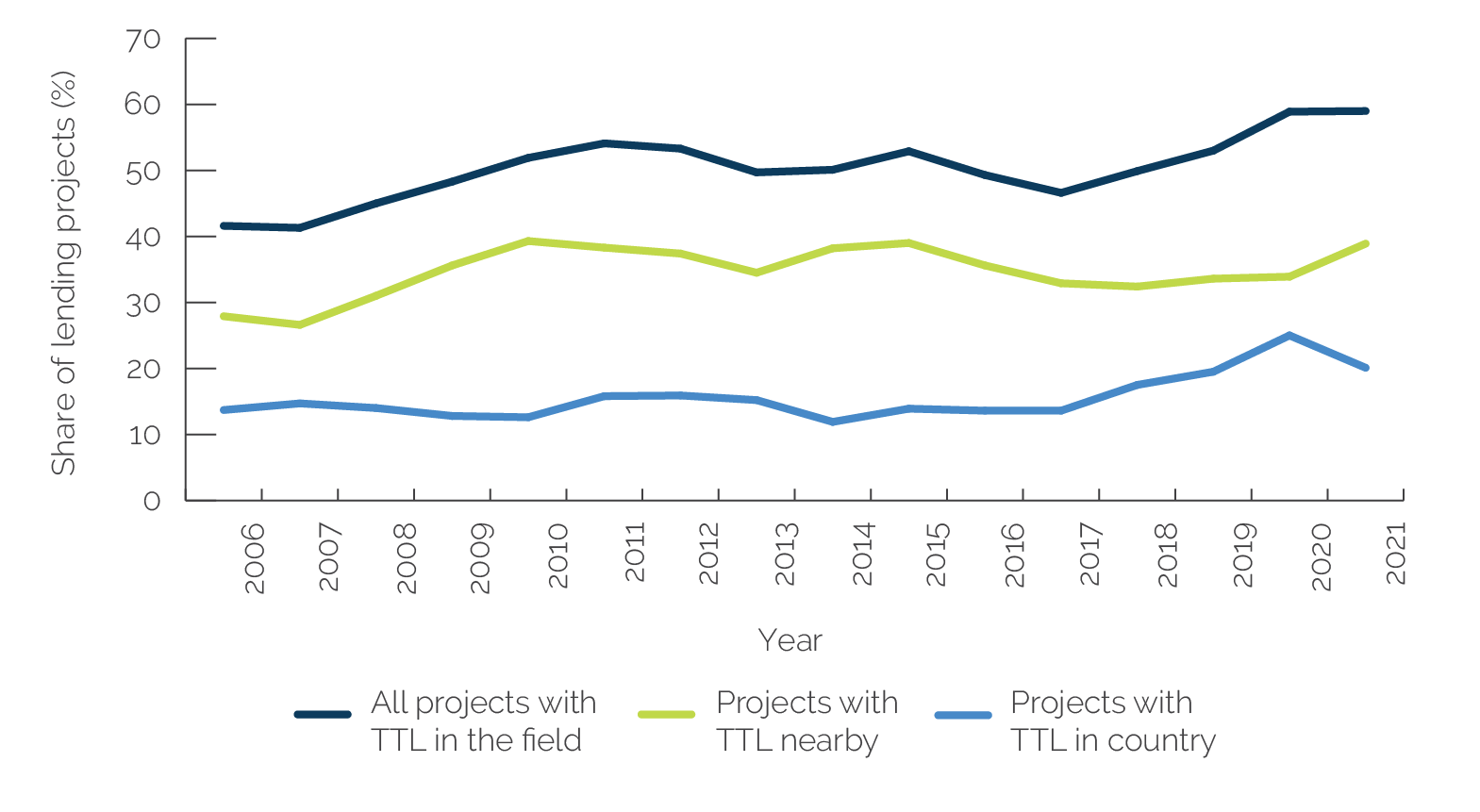

The World Bank’s strategic focus on FCS countries did not lead to a sharp increase in projects being managed directly from the FCS locations, but the overall trend is upward since 2018. On average in FY06–21, nearly half of lending projects in FCS countries were managed from the field locations, but only 16 percent of those projects were managed from the recipient FCS countries. Since 2018, however, there is a slow but steady increase of ADM TTLs located in project countries, the highest since 2006 (figure 2.7). Likewise, about 40 percent of country-focused ASAs were led from the field, but only about 12 percent of those were led by TTLs in the recipient countries.

Figure 2.7. Lending Projects in FCS Countries Managed from the Field

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis of human resources and project portfolio data.

Note: “TTL in country” means the TTL is in the project recipient country; “TTL nearby” means the TTL is not in the project recipient country but somewhere in the same Region. FCS = fragile and conflict-affected situations; TTL = task team leader.

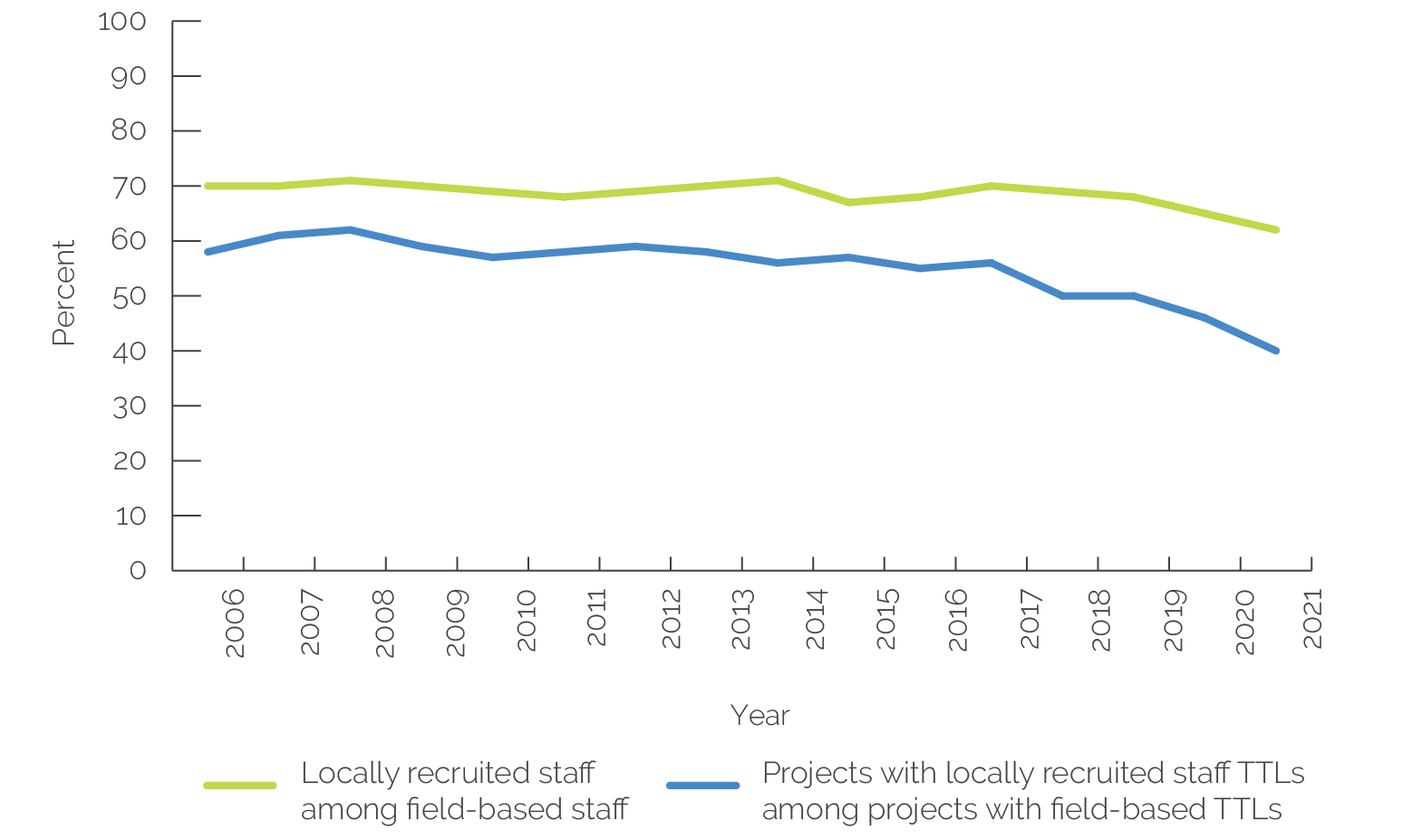

Since 2013, fewer LRS are leading projects, and the trend is downward in recent years. Although the share of locally recruited professional staff in country offices has changed little since the early 2000s, there was a decline in the share of projects led by locally recruited TTLs over the same period. This may have to do with the increasing number of projects with co-TTLs after 2013. Under this co-TTL model, the IRS often assumes the ADM role, and the LRS assumes the non-ADM supporting role (figure 2.8), resulting in fewer LRS staff leading projects. In 2021, the share of LRS TTLs has been the lowest since 2006.

Figure 2.8. Locally Recruited Staff in the Field, and Lending and Advisory Services and Analytics Projects Managed by Locally Recruited Staff in Project Countries

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis of human resources and project portfolio data.

Note: TTL = task team leader.

- This chapter covers the World Bank’s global footprint in the World Bank’s client countries that have investment lending operations. It covers the staffing trends based on human resources data from fiscal year (FY)1996 to FY21 and project data from FY06 to FY21.

- The Strategic Compact was an agreement “between the World Bank and its shareholders: to invest $250 million in additional resources over a three-year period to deliver a fundamentally transformed institution—quicker, less bureaucratic, more able to respond continuously to changing client demands and global development opportunities, and more effective and efficient in achieving its main mission—reducing poverty” (World Bank 2001).

- As a complex matrix organization with many moving parts, the World Bank often adjusts different aspects of its organizational structure and decision-making to improve the delivery of its corporate goals. Although many of these changes are beyond the scope of this evaluation, some affect how central unit (headquarters) works with the periphery (Regions and Country Management Units).

- Decentralization slowed down or even reversed in some sectors already in 2012 due to high costs of placing international staff in the field. In certain places and sectors (for example, in Africa’s transport sector in 2012), the World Bank even started to bring IRS back to Washington, DC, because of high costs.

- In this evaluation, the analysis of human resources applies only to the World Bank’s professional staff in operations, which includes grades GE and up in headquarters and field offices, and excludes staff in institutional, governance, and administrative units.

- The 15th Replenishment of the International Development Association outlined its strategy, instruments, and operational response to support fragile states.

- Some fragile and conflict-affected situation (FCS) countries, such as Afghanistan or Myanmar, receive more staff, especially internationally recruited staff, because those countries are prioritized by international donors.

- Locating staff in FCS countries costs about 40 percent more than locating staff in non-FCS countries. FCS countries also have higher security spending.

- Large decentralized organizations rotate their international staff between central and Regional units for multiple purposes. First, international staff and managers can apply knowledge from other units and share innovations in new locations. Second, international staff help transfer the organization’s culture to the field by reinforcing the organization’s policies and practices and improving networking opportunities for staff. Third, field positions expose them to diverse experiences and cultures, improving their technical and managerial skills and personal learning (Edström and Galbraith 1977; Hocking, Brown, and Harzing 2004).

- Third-country nationals would either become local staff after five years of service or move to another country office.

- Task team leaders are used as a proxy for decision-making because they have accountability and decision-making responsibilities for projects.

- The evaluation’s data on project task management covers FY06–21.

- In this evaluation, the focus is on the portfolio of country-focused advisory services and analytics, excluding those that have Regional and global focus. With country-focused advisory services and analytics, the World Bank supports clients through advice and analysis to design or implement better policies, strengthen institutions, build capacity, inform development strategies or operations, and contribute to the global development agenda.