Some aspects of organizational incentives in the World Bank have not changed all that much since Wapenhans’ review.Projects remain the mainstay of the Bank’s financial business model, it faces pressure to lend and disburse, its Global Practices compete for new business, and staff careers are made on taking projects to the Board.

However, the World Bank did create new tools to improve quality of design and implementation in response to the portfolio quality challenges identified by Wapenhans. The Bank made quality at entry and quality of supervision critical components of how it manages and assesses the development effectiveness of its operations. It introduced routine portfolio monitoring and flags for “problem projects”, reformed the country programming process, and instituted powerful Country Directors in charge of selectivity. It created a dedicated Committee on Development Effectiveness (CODE) within the Board. The role of independent evaluation (reporting into CODE) was strengthened, and for a while, there was an influential Quality Assurance Group.

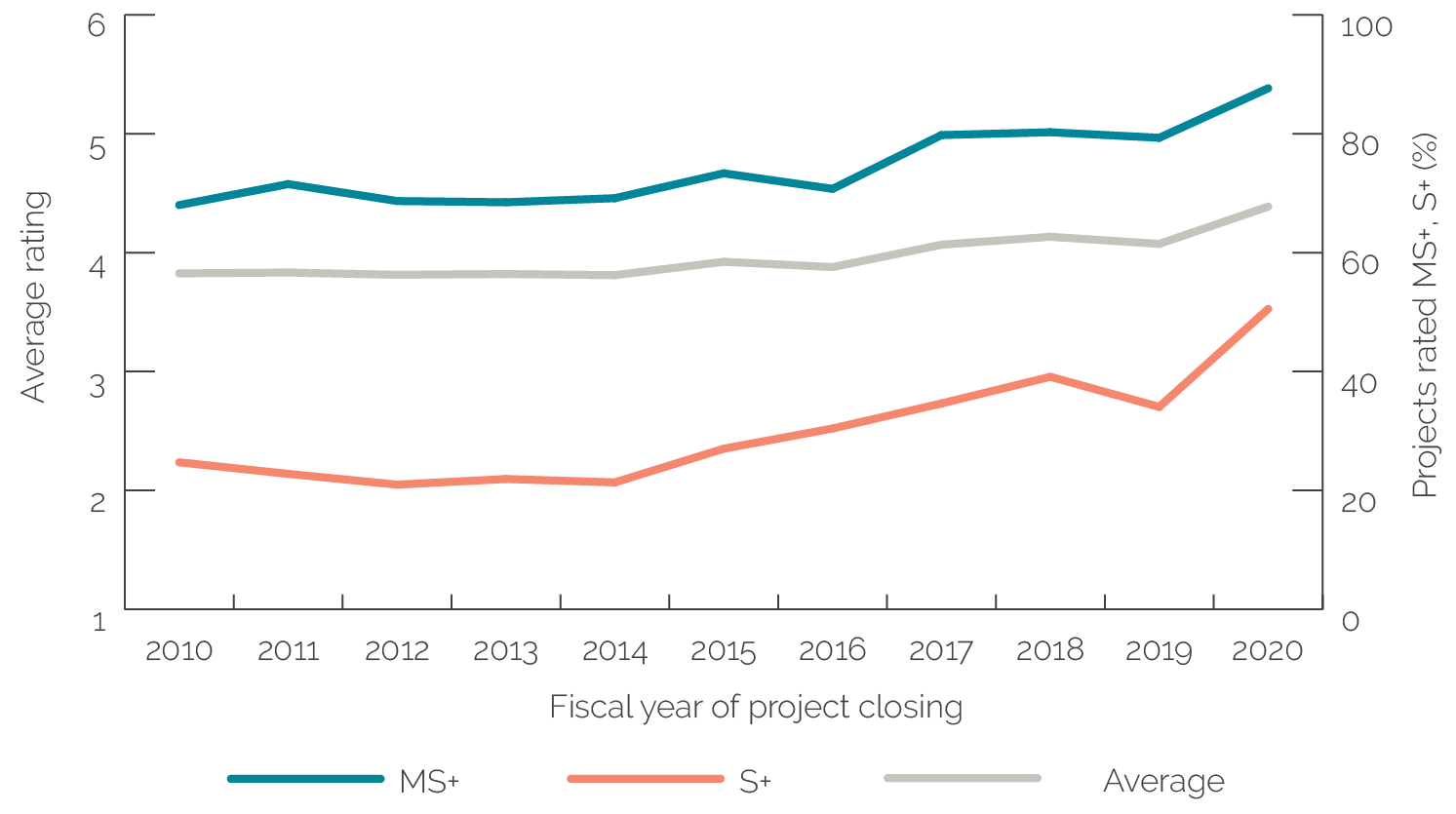

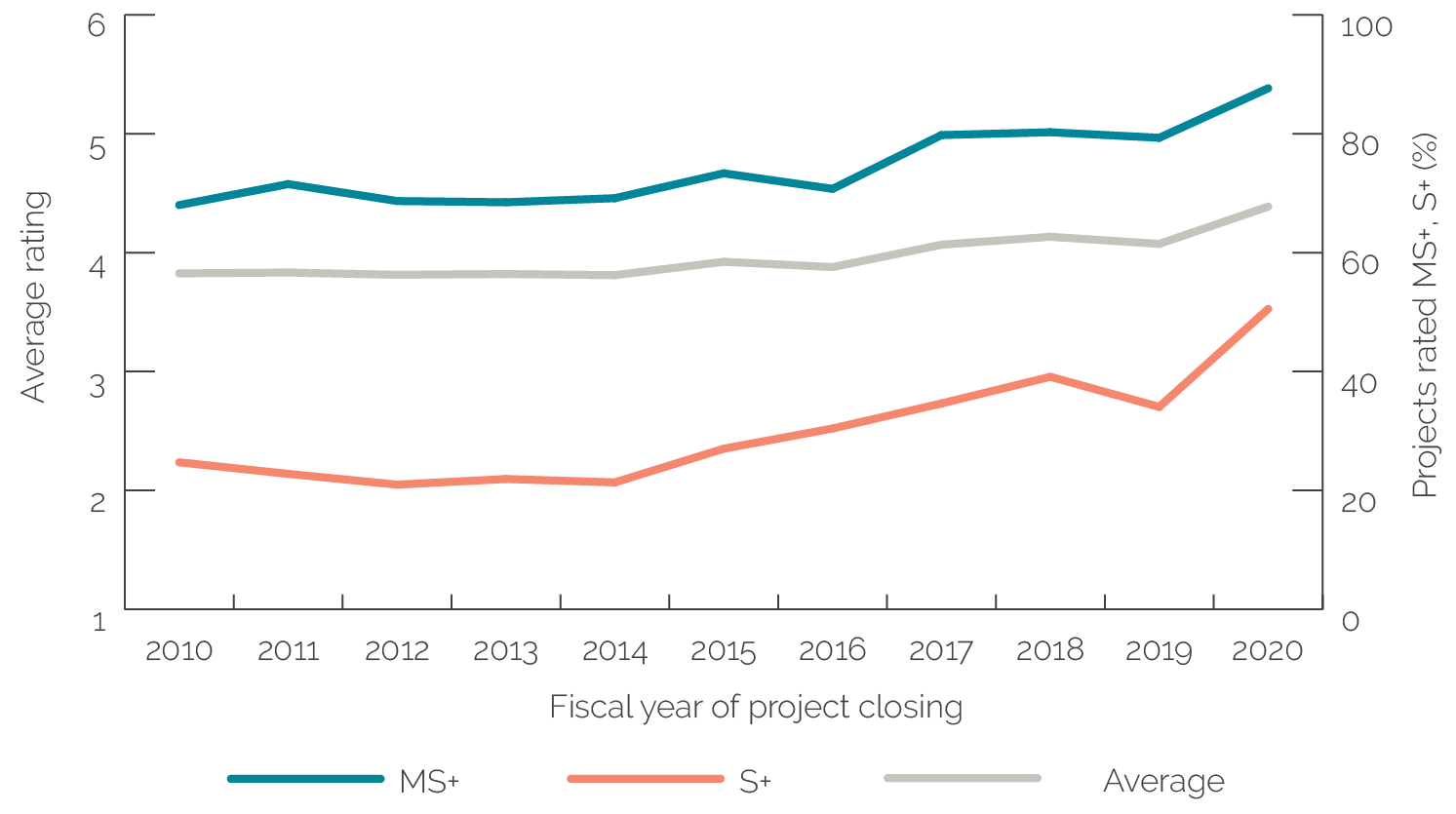

These tools and initiatives have served the World Bank well. The very latest ratings of project performance are high and improving (figure 1). Selectivity at country level, and the related project designs, are better today.

Instead, the Bank faces new challenges.

Figure 1: World Bank Project Outcome Ratings, by number of projects

Source: Results and Performance 2021.

The challenge of managing for outcomes

The World Bank has solid measures of its projects’ performance: its operational staff self-evaluate projects in what are called implementation completion reports (ICRs), and IEG validates every self-evaluation and rates the Bank project. At the same time, these ratings do not give a full picture of how far and how well World Bank Group financing is moving the needle on development outcomes at the sector, sub-national or national level. For an organization that prides itself on being driven by data and evidence and with a strong mission orientation, there is room for more systematic outcome evidence that takes in both long term development results and the need to adapt quickly to short term crises.

For example, IEG’s evaluation of the Bank Group’s country-level results system found that this results system emphasizes reporting and upward accountability, but does not do much to support teams’ efforts to learn and course correct. The results measurement toolkit is more suited to tracking outputs and direct results of individual operations than outcomes achieved through multifaceted country engagements. Incentives focus on meeting targets and reporting, rather than creating space for collective learning or making course corrections, and, at times, go counter to staffs’ intrinsic motivation to pursue high-level outcomes (see an earlier blog on this). As a consequence, staff navigate by judgment while some results systems are used as check-box exercises and to ensure compliance.

The challenge of selectivity

Whereas the World Bank has systems in place to ensure selectivity at project level, the selectivity challenges today show up at the regional and global levels. The global development space is crowded and contested. Stakeholders and shareholders advocate for the issues and global public goods that they care most about to be prioritized by the World Bank Group. New shocks and crises demand a response while deep-seated and persistent development challenges in the poorest and most fragile environments continue. The many global partnerships and trust funds housed at the Bank both exert pressure for, and help it work on, many of these issues, particularly in the knowledge space.

Agendas are therefore busy, at corporate, sectoral, and regional levels, as described in IEG’s evaluation of the Bank Group’s global work and convening power.

While the country programming process seeks to ensure selectivity for country work, it is harder to assess how well it works for global issues. Regional and country units decide which global priorities get embedded in country programs. But they have little say in selecting global engagement priorities in the first place. There are corporate indicators and a raft of policy commitments for IDA, the World Bank’s fund for the poorest countries, covering gender, climate co-benefits, fragility and citizen engagement, but, beyond this, the Bank struggles with a vision for how the country work and the global work should join up.

Climate change and multiple crises have put the urgency of collective action firmly back on the global agenda. The World Bank Group’s new crisis response framework is seeking to put more emphasis on regional level engagement; yet, it can be hard for the Bank Group to find its foot on some global and regional issues and challenges, especially when the solution requires a response beyond what can be embedded in country programs.

The challenge of assessing impact remains

The World Bank internalized the lessons of Wapenhans’ evaluation by cleaning up its portfolio quality and creating new tools and processes to manage lending quality. Thanks to this, the Bank has been able to grow its lending, strengthen its global relevance, and respond to many new priorities without apparent sacrifice of quality. However, having settled on ratings from the project self-evaluation system as the dominant results metric, the Bank still lacks good measures of the high-level outcomes of its work. Thirty years on from Wapenhans, the challenge of assessing impact remains, only now it has moved from the project level to the national, regional, and global levels.

While the Wapenhans report was produced by an ad hoc task force, today the World Bank Group has in IEG a permanent institutional home for credible evaluation, conducted by people who are inside the organization yet independent of management. Next year marks the 50th anniversary of independent evaluation at the World Bank Group.

Add new comment