Having cut my teeth on issues of debt sustainability in the mid-1990s working on the design and implementation of the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative (HIPC), I can’t help but have a feeling of déjà vu as concerns grow over debt sustainability in low-income countries (LICs). Unambiguously, the COVID pandemic has made things worse, but it is worth remembering that the resurgence in debt stress in LICs was evident and under active discussion in policy circles well before February 2020.

Since 2013, the number of countries eligible for concessional financing from the World Bank at high risk of, or in, debt distress has almost tripled (from 13 to 35 (33 in 2019)) and the average debt-to-GDP ratio has increased from about 40% to 60%. This occurred alongside significant support from the international community (and the World Bank in particular) to improve the debt management capacity of LICs. Despite this, and against a backdrop of persistently low global interest rates, median interest payments from LICs rose 128% between 2013 and 2018.

Yes, hindsight is 20/20. This blog is not an attempt to claim that the current situation should have been easily anticipated (although that proposition is subject to debate) but rather to emphasize the urgency of learning from the past. It is true that many of the factors underpinning the rise in pre-COVID debt stress such as persistently low global commodity prices were not easily anticipated. The Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) recently completed the third in a series of macro-fiscal evaluations that consider, among other things, the evolution of debt stress in LICS, and offer insights to enhance the effectiveness of Bank Group support to strengthen fiscal resilience in LICs.

IEG’s February 2021 Evaluation of World Bank Support for Public Financial and Debt Management in IDA-eligible Countries, focusing on the decade following the 2008 global financial crisis, notes that many LICs sharply increased non-concessional and shorter-term borrowing to finance “growth enhancing" public investment to close infrastructure gaps and meet global development goals. Appropriately, development partners extended significant support to enhance debt management capacity over this period, with many positive results in terms of the number of countries that met minimum standards of good practice for debt management.

However, as the IEG evaluation demonstrated, this was not systematically accompanied by similar attention to the quality of public investment management (PIM), which includes the ability to systematically and transparently scrutinize the costs and benefits of public investment, in infrastructure as well as other sectors. Indeed, over the last decade, public investment management diagnostics were undertaken by the Bank for less than half of countries eligible for concessional resources from IDA, the World Bank’s fund for the poorest countries, with demand concentrated among higher-income LICs. Of the 32 IDA-eligible countries at high risk of, or in, debt distress in FY18, only 10 had received support over the previous decade from the World Bank to improve their public investment management capacity.

In July 2021, IEG released its evaluation of the World Bank Group Contributions to Addressing Country-level Fiscal and Financial Sector Vulnerabilities. This evaluation sought to assess the adequacy of the Bank Group support for macro-fiscal and financial sector crisis preparedness. It found that outside the context of stabilization efforts, the World Bank Group was less effective in working with clients to proactively expand buffers, strengthen institutions, and build capacity for better preparedness and economic crisis management. It also pointed to optimistic bias in the growth assumptions underpinning debt sustainability analyses (DSAs) as well as important gaps in the quality and availability of data on the contingent liabilities of state-owned enterprises.

IEG will soon release its Early Stage Evaluation of IDA’s Sustainable Development Financing Policy (SDFP). The SDFP was adopted in July 2020 to incentivize IDA-eligible countries to achieve and maintain debt sustainability by moving toward more transparent and sustainable financing. The core of SDFP incentives is the requirement for countries that, according to the DSA, are at moderate to high risk of debt distress (or in debt distress) to implement performance and policy actions (PPAs). PPAs are intended to enhance debt transparency, promote fiscal sustainability, and strengthen debt management. IDA-eligible countries estimated to be at low risk of debt stress using the DSA are exempt from the requirement to implement PPAs.

Noting that one-third of countries that saw an elevation in their risk of debt distress over the past decade also experienced a two-level deterioration in less than three years, the evaluation recommended that a DSA finding of “low risk of debt distress” should not be sufficient to exempt an IDA-eligible country from implementing PPAs. Given the rapidity with which debt stress can build, and the well documented optimistic tendency of the DSA, the evaluation recommended that the requirement to implement PPAs not be determined solely using the DSA. While IEG did not suggest what other criteria might be introduced for PPA exemption, LICs currently assessed at low risk of debt stress might also be required to demonstrate a minimum standard of data transparency, including with respect to contingent liabilities associated with state guarantees and state owned enterprises.

Where does that leave us now? Can we use the lessons from these three IEG evaluations to plot a path to a more resilient foundation for responsible and productive use of credit? The answer is an unequivocal “yes”.

The recent Development Committee communique shines a light directly on the importance of debt transparency and debt management capacity, calling for the World Bank Group and the International Monetary Fund “to continue coordinating efforts to strengthen debt transparency and debt management capacity, including a process to strengthen the quality and consistency of debt data and improve debt disclosure, while helping many LICs and Middle Income Countries achieve debt and fiscal sustainability“.

No one credibly disputes that greater transparency on the amounts, terms and conditions of sovereign borrowing is needed or that improvements in the ability of governments to manage their debt to minimize cost and risk is a sine qua non for responsible macroeconomic management. These are important initiatives that should continue.

But with the costs of a potential debt sustainability crisis running well into the billions, they are not enough, and IEG’s three evaluations provide some guidance on what more might be considered. First, we need to pay greater attention to the quality of spending that is financed with official sector borrowing. Indeed, this was clearly recognized by IDA Deputies in the context of the 19th Replenishment of IDA in their statement that “the first challenge is to assist IDA countries to ensure that the benefits [of borrowed resources] exceed the costs of servicing their debt. IDA and other partners can help by supporting initiatives that enhance capacity in areas such as public finance management, public investment management… and debt management”.

As a start, Multilateral Development Banks, including the World Bank, should routinely include in the set of core economic and fiscal diagnostics used to inform country strategies and set priorities, an assessment of the quality of public investment management, such as the IMF’s Public Investment Management Assessment (PIMA). Countries receiving concessional support from the World Bank and seeking to be exempt from PPA implementation might also be required to regularly conduct (e.g., every five years) a Debt Management Performance Assessment (DeMPA) to provide clarity on where greater attention is needed on debt transparency and management, with a presumption of DeMPA publication. There are other data transparency standards that could usefully be strengthened, including the World Bank’s Debt Reporting System (DRS), whose coverage could be expanded (to include borrowing by State Owned Enterprises) and incentives for compliance could be strengthened.

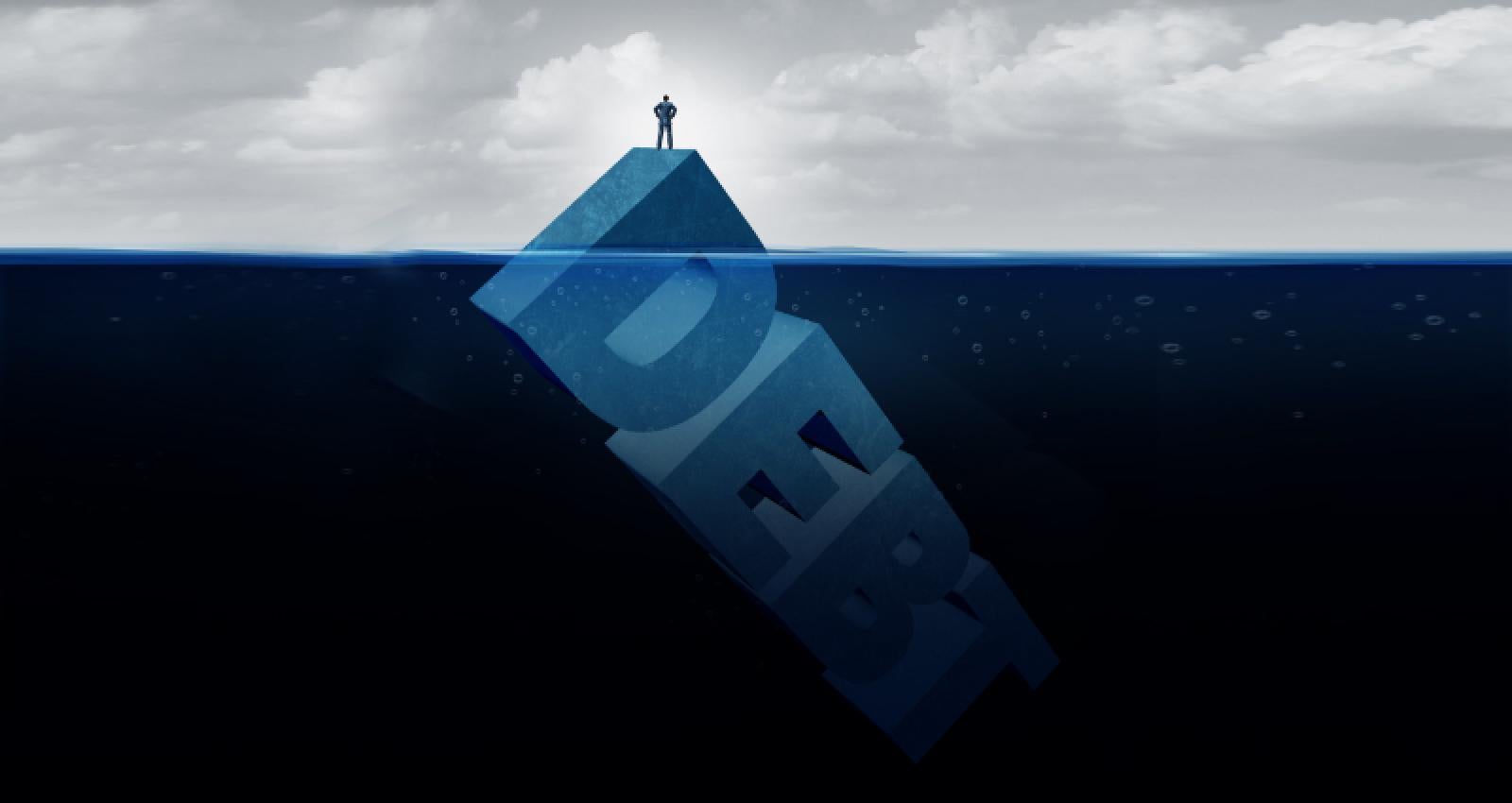

No one can say that the above actions would have prevented the pre-COVID resurgence of debt stress in IDA-eligible countries. But the intuitive appeal of proactive measures that promote higher quality public investment and better and more complete data about the borrowing behavior of governments, including state guarantees and state-owned enterprise debt, should not be controversial. And none of these actions are pro-cyclical, which means they can be implemented even in the midst of the COVID crisis (with donor support where capacity building is necessary). They might even enhance the resilience necessary to help avert the next hidden debt crisis or resurgence of debt stress.

Add new comment