Making Procurement Work Better

Chapter 5 | Procurement Capacity Strengthening and Support

Highlights

The World Bank increased its support for strengthening clients’ procurement capacity, with a greater emphasis on global support and trust fund financing but less support in Africa and in countries that have the lowest procurement capacity. In fiscal year 2017–23, 65 percent of procurement capacity strengthening activities occurred in countries with higher procurement capacity.

Country-level capacity strengthening is fragmented, is not well measured, is only partially achieved, and often focuses on short-term activities rather than sustaining long-term change for scaled-up results in the country. Less than 20 percent of Country Partnership Frameworks had a significant emphasis on procurement capacity strengthening.

Procurement capacity strengthening resources could better target pressing needs and persistent issues that affect the performance of the World Bank portfolio, especially in countries where procurement is a main bottleneck to development achievements in projects.

The World Bank’s procurement staff have limited time to support clients and strengthen their capacity, especially in Western and Central Africa and fragile and conflict-affected situation countries, leading to more procurement issues and delays. Hands-on expanded implementation support fills some of these staffing gaps. In fragile and conflict-affected situation countries, about half of procurement staff are responsible for 10 or more projects. In Western and Central Africa, where 30 percent of all projects supported by investment project financing take place, staff support, on average, about 20 projects.

Hands-on expanded implementation support improves procurement performance, and the World Bank could apply it more strategically. Combining hands-on expanded implementation support with knowledge sharing and coaching could create a pool of experienced procurement specialists within the country to help enhance the long-term performance of projects and push what could be achieved in the portfolio.

This chapter evaluates the World Bank’s progress and challenges in supporting clients and strengthening their procurement capacity. This includes their capacity to execute procurements according to World Bank standards and the seven principles described in chapters 1, 2, 3, and 4. It also includes clients’ capacity for public procurement more generally—that is, in-country procurement capacity strengthening. The evaluation examines World Bank capacity strengthening interventions, including both lending projects and advisory services and analytics (ASA), country strategies, results indicators and their achievement, and staff support for capacity strengthening. Evidence also derives from the case studies, surveys, and portfolio analysis. This chapter finds that the World Bank increased its focus on strengthening clients’ procurement capacity since the reform, but that its efforts could be more strategic and well measured and could better address the most pressing and common procurement needs in its project portfolios.

Procurement specialists and sector specialists of other Global Practices lead the World Bank’s procurement capacity strengthening efforts. Procurement specialists perform capacity strengthening at the project level through day-to-day advice, short-term training, and process reviews. By contrast, procurement specialists and other sector specialists—including, among others, governance, public financial management, and transport specialists—strengthen procurement capacity at the country level through lending or ASA. This support may involve training client procurement specialists; assessing procurement systems; promoting legal, institutional, regulatory, and other system changes; and supporting the application of specific procurement methods.

Increased Capacity Strengthening since the Reform and a Strategic Approach That Could Make It More Valuable

The World Bank increased its country-level capacity strengthening support after the 2016 reform. The biggest increase occurred in global support, and the biggest regional decrease occurred in Africa. The number of procurement capacity strengthening interventions increased by 8 percent since the 2016 reform (appendix D). In FY10–16, the World Bank provided this support to 94 countries; in FY17–23, this support increased to 105 countries. The biggest jump took place in global support, or support that is directed to no particular country, which increased by fourfold in FY17–23 compared with FY10–16. Examples of global interventions include global studies on e-procurement, training on procurement rating systems, and development of procurement training and guidance materials. With regard to Regions, interventions in South Asia nearly doubled, whereas in Africa, where procurement capacity is among the lowest (appendix E), they declined by nearly 30 percent.

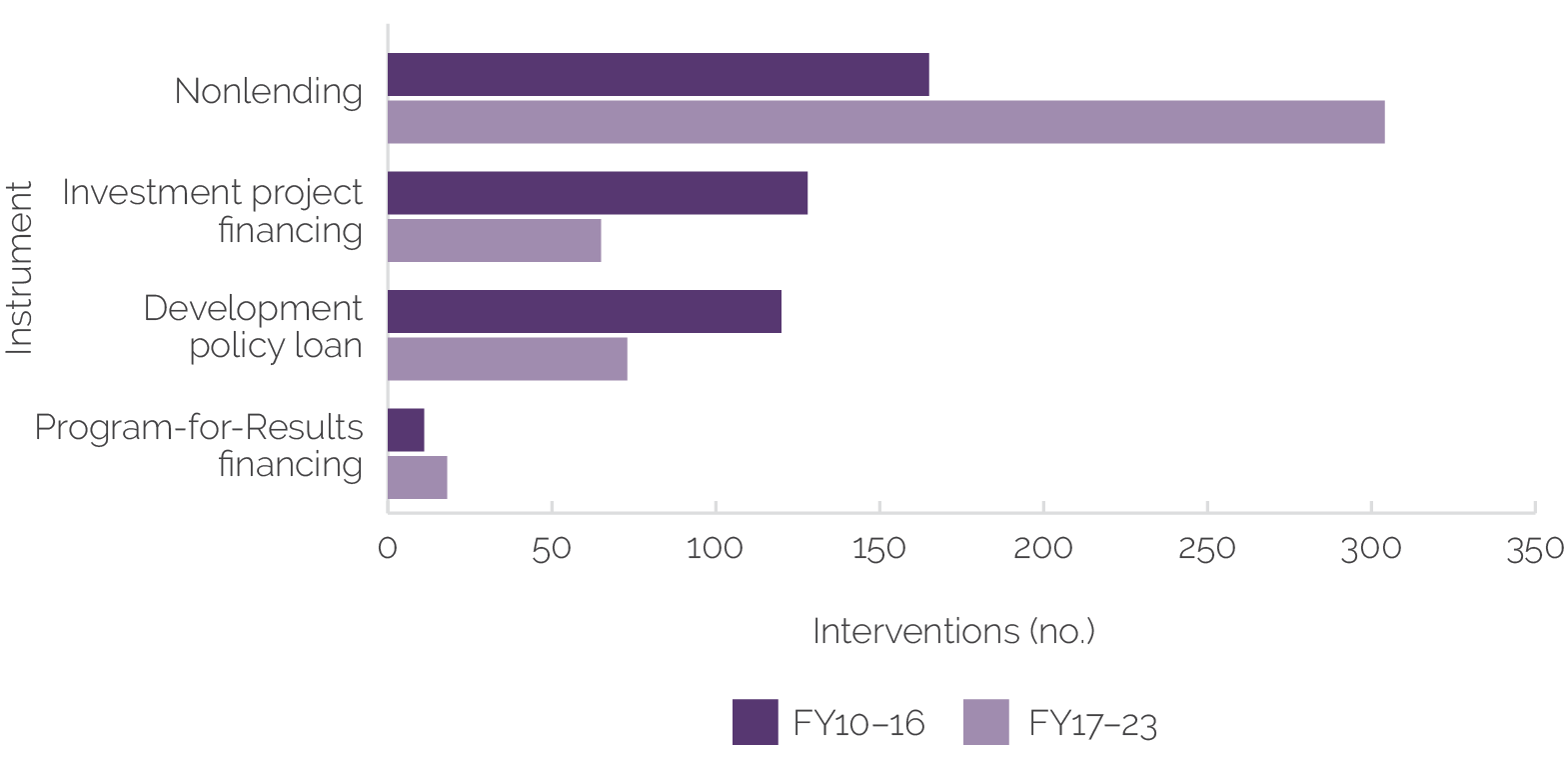

The World Bank’s procurement capacity strengthening support since 2016 relies heavily on trust funds, with limited support coming from lending. The number of ASA used for capacity strengthening increased by about 50 percent from FY10–16 to FY17–23 (figure 5.1). Trust funds largely funded this increase, particularly the Global Procurement Partnership multidonor trust fund, which has provided over $10 million of financing since 2016. However, procurement capacity strengthening has involved fewer development policy loans and IPF, although some lending still includes capacity strengthening activities and relevant policy actions.

Figure 5.1. Procurement Capacity Strengthening by Instrument, Fiscal Years 2010–16 and 2017–23

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Investment project financing includes other investment lending types, such as specific investment loans, technical assistance loans, and emergency recovery loans. Nonlending includes advisory services and analytics and other knowledge products supporting the strengthening of procurement capacity. FY = fiscal year.

The World Bank’s country strategies could more strongly emphasize procurement capacity strengthening. IEG’s 2014 procurement evaluation recommends that the World Bank develop a strategic, coherent approach to procurement capacity strengthening in client countries that is anchored in country strategies to facilitate longer-term change rather than a frag-mented set of opportunistic interventions.1 Despite this recommendation, in 61 percent of the most recent Country Partnership Frameworks (CPFs)—the principal strategy document for country programs—procurement capacity strengthening is absent or superficially mentioned. In 20 percent of CPFs, the evaluation classifies procurement capacity strengthening as somewhat significant within the strategy—that is, the CPFs mention procurement capacity strengthening activities but not under its main pillars and priority areas and without an emphasis on results. In about 19 percent of CPFs, the evaluation classifies procurement capacity strengthening as significant or highly significant—that is, it includes suitable activities that lead to im-provements in procurement capacity and indicators to measure results.2

The World Bank could consider more rapid and focused diagnostics to inform its country-level procurement capacity strengthening. Interviews with procurement staff show that World Bank staff decide on the country-level procurement capacity strengthening activities based on (i) the results of the Methodology for Assessing Procurement Systems (MAPS) that uses a rigid framework to benchmark and compare results across countries; (ii) other assessments, such as Public Expenditure Reviews; (iii) rapid ad hoc diagnostics; and (iv) client requests. MAPS is the primary diagnostic tool to assess national procurement systems in their entirety.3 However, of the 20 percent of country strategies with procurement capacity strengthening deemed significant or highly significant, about one-third had completed a MAPS assessment. This may not be surprising given that MAPS is a time-consuming and expensive exercise. Moreover, as noted in IEG’s 2014 procurement evaluation, MAPS assessments “provide a ‘snapshot’ of the [procurement] system, rather than a roadmap for reform” (World Bank 2014, 9). As such, rapid diagnostics are likely more useful for informing strategic decisions on procurement activities.

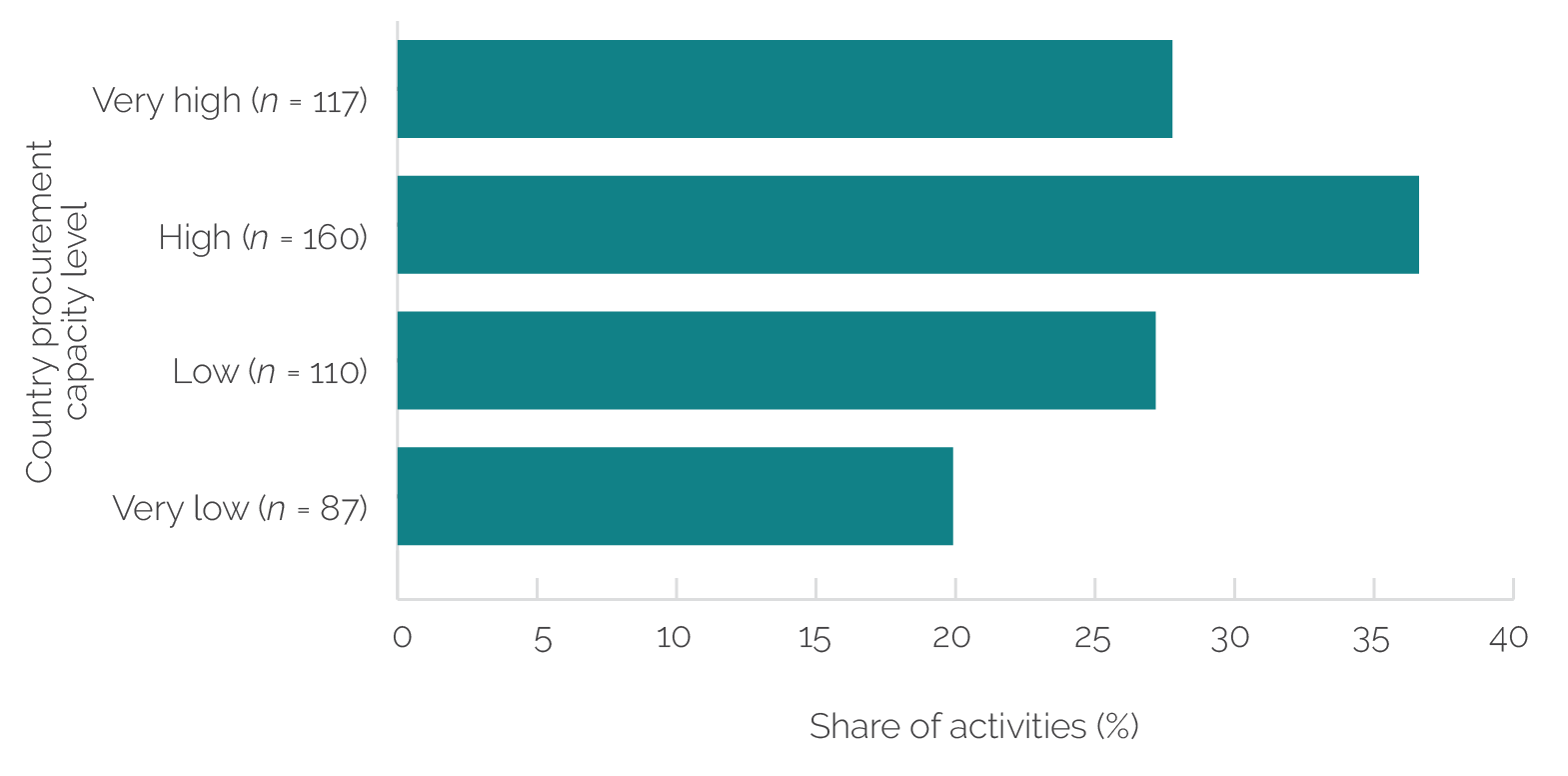

Capacity strengthening activities focus on countries with higher procurement capacity despite lower-capacity countries having more procurement issues. In FY17–23, 59 percent of procurement capacity strengthening activities occurred in countries with high or very high pro-curement capacity compared with 41 percent in countries with low or very low procurement capacity (figure 5.2). For example, Cambodia, Guinea-Bissau, and the Republic of Congo are among the countries with the lowest procurement capacity and many procurement issues that negatively affect the World Bank portfolio, yet each country received one capacity strengthen-ing intervention. The greater focus on higher-capacity countries might be explained by the lack of a strategic approach to in-country procurement capacity strengthening.

Figure 5.2. Procurement Capacity Strengthening by Country Capacity Level, Fiscal Years 2017–23

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The figure shows the percentage of activities in countries by the procurement capacity level of the country. Activities refer to procurement capacity strengthening activities in World Bank interventions, such as investment project financing and advisory services and analytics. One intervention may have multiple activities. Procurement capacity levels of countries are from the country situation analysis in appendix E. The total number of activities is 474.

The World Bank’s procurement capacity strengthening could be more continuous to influence sustained institutional change. Since the 2016 reform, in some countries, the World Bank discontinued or decreased the intensity of its capacity strengthening support compared with before the reform (FY10–16).4 Bangladesh, Benin, China, Djibouti, Ethiopia, India, Kosovo, Liberia, Pakistan, Tanzania, and Uganda stand out for having high or very high continuity, defined as numerous interventions on a continuous basis without interruption during both periods. Even if a country receives continuous World Bank capacity strengthening support, it is not uncommon that the World Bank units providing the support and the entities in the country receiving it differ for most of the interventions, leading to fragmented support. Literature acknowledges capacity strengthening as a long-term process (Eade 2007; Lusthaus, Adrien, and Perstinger 1999; Vogel 2012); hence, fragmentation, sporadicity, and discontinuity in support reduce the chances of influencing institutional change.

Capacity Strengthening and Procurement Issues in the Portfolio

Countries with access to experienced procurement specialists tend to successfully implement project procurement activities. As discussed in this chapter, the number of procurement issues reported in project ISRs decreases for projects that receive HEIS, and fewer issues reported in ISRs, in turn, are linked to higher procurement performance ratings (appendix E). The case studies (appendix F) also show that having experienced procurement specialists in project implementation units helps clients successfully implement procurement activities. For example, in Niger and Mozambique, projects with experienced client procurement staff had fewer procurement-related problems and delays, whereas projects without them experienced frequent problems and delays. The survey reflects this finding—TTLs and World Bank procurement staff report that the unavailability of procurement experts in client countries undermines project implementation.

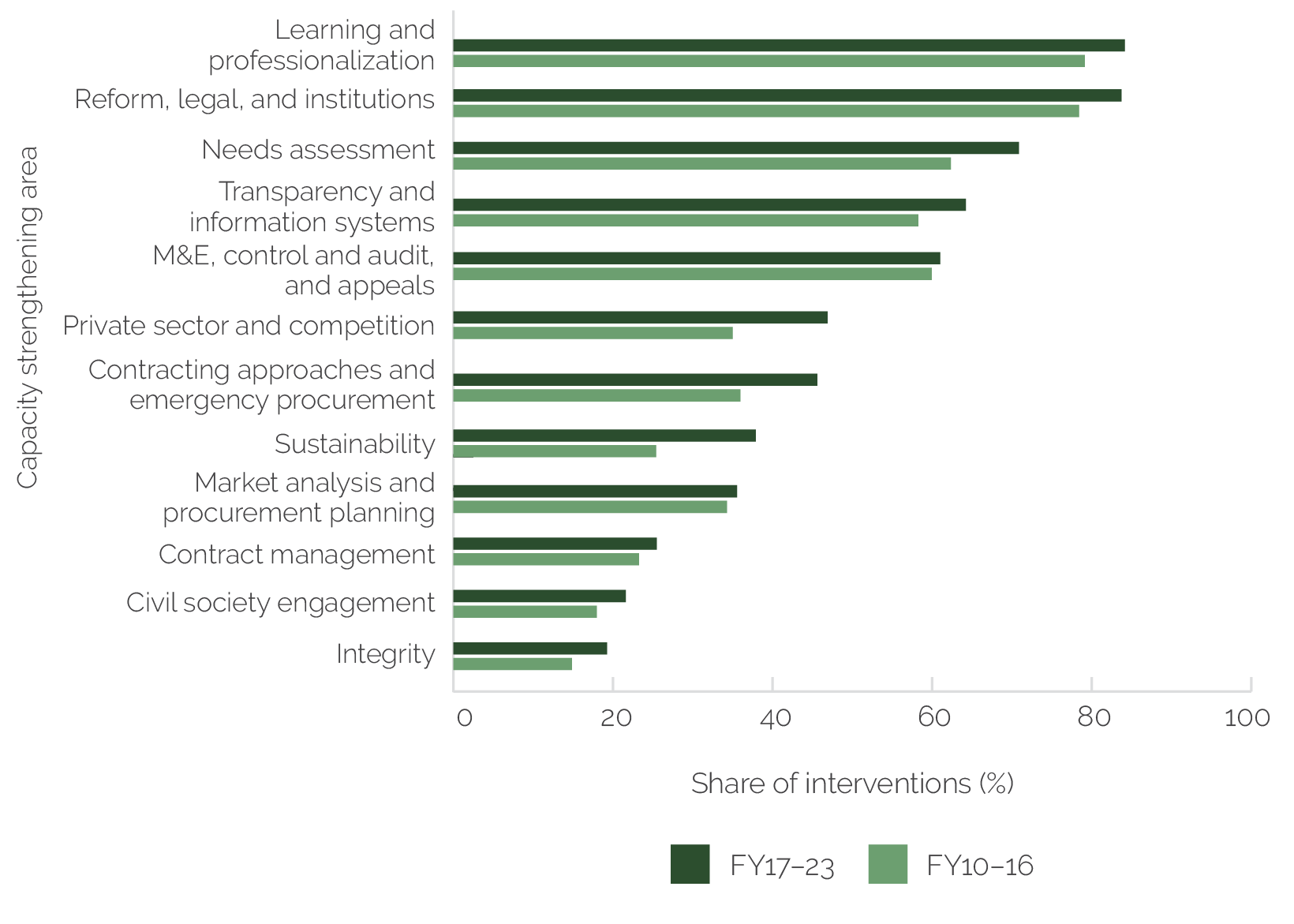

The World Bank could better emphasize building sustained human capacity in countries. Figure 5.3 shows that the highest percentage of capacity strengthening efforts are classified as “learning and professionalization” activities that include holding trainings and workshops, providing technical advice, and preparing learning materials, especially e-learning programs. Most of these activities are short term and topic specific and not aimed at building deep procurement expertise. However, there are learning and professionalization activities in some countries that build sustained human capacity. Such activities include supporting country institutions to provide procurement training, creating procurement career paths, and certifying procurement staff. Examples include certification programs in universities, procurement networks in India and Liberia, and central procurement hubs that provide mentoring support.

The World Bank provides limited capacity strengthening support for the procurement approaches introduced in the 2016 procurement reform. The case studies show that when clients become familiar with procurement approaches, they are more likely to use them (appendix F). For example, legislation in an Eastern European country encourages rated criteria in procurements, and, as a result, the client showed a willingness to use this approach in the project. The same client also successfully incorporated sustainability in procurement to foster women’s participation in road works. Despite the importance of familiarity for the uptake of new procurement approaches, a small proportion of World Bank interventions in FY17–23 strengthened capacity in sustainable procurement (figure 5.3).

Figure 5.3. Interventions by Capacity Strengthening Area, Fiscal Years 2010–16 and 2017–23

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The figure captures 884 World Bank interventions with procurement capacity strengthening. Of these interventions, 417 are part of FY10–16 and 467 are part of FY17–23. The procurement capacity strengthening areas were identified through a keyword search in the intervention name, objective, and other text fields. The percentages in the graph do not add up to 100 because interventions can support several areas of procurement capacity strengthening. FY = fiscal year; M&E = monitoring and evaluation.

Support to strengthen a country’s procurement capacity rarely targets systemic procurement processing issues. Project-related procurement issues identified in ISRs and the case studies are often related to weak country procurement systems and insufficient human capacity. Examples from ISRs include issues with bidding, contract management, procurement documents and standards, finding project procurement specialists in projects, and clients’ procurement capacity (appendix E). Additional examples from the case studies include difficulties with preparing technical specifications, terms of reference, evaluation criteria, and evaluation reports and lengthy local review, complaint, and appeal processes. Many of these issues are similar across projects in a country, and they often also negatively affect the country’s public procurement activities. Despite the persistence of these issues, the review of country-level procurement interventions since the 2016 reform shows that the World Bank’s capacity strengthening support rarely targets them.

Opportunities for Capacity Strengthening to Be More Ambitious and Better Measured

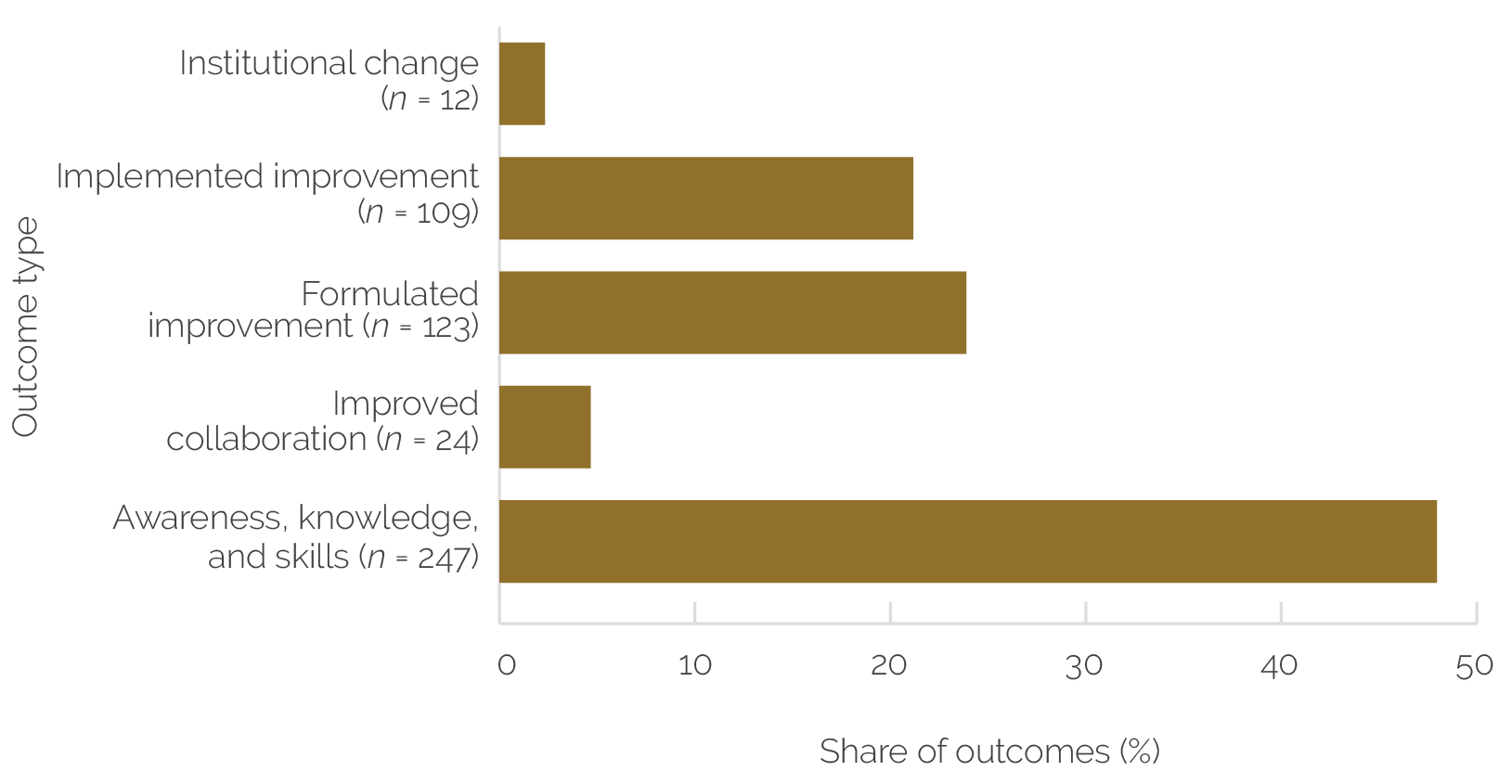

Most in-country procurement capacity strengthening support focuses on increasing knowledge but rarely focuses on ambitious institutional change. Such a change should be the ultimate outcome of capacity strengthening. Examples of support that focuses on increasing awareness, knowledge, and skills are diagnostic work to identify national procurement system weaknesses, procurement learning modules, and dissemination of good procurement practices in specific sectors. The other common capacity strengthening support aims at helping clients formulate and implement procurement improvements—for example, designing and operationalizing e-procurement systems. Figure 5.4 shows that only about 2 percent of capacity strengthening interventions aim at institutional changes related to the procurement principles. Examples of interventions supporting these objectives include helping countries increase reporting on corruption, improve procurement management scores, and reduce procurement times. A possible explanation for the limited number of institutional change interventions is that they are difficult to achieve by the time an intervention ends and results are reported.

Figure 5.4. Intermediate Outcomes Targeted by Capacity Strengthening, Fiscal Years 2017–23

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Outcome types capture intermediate outcomes achieved or likely to be achieved through the fiscal year 2017–23 World Bank support to strengthen procurement capacity. Examples of implemented improvement include the use of an e-procurement system or formal approval of a new procurement law. Examples of formulated improvement are the design of an e-procurement system, drafting of a procurement code or action plan, and development of a public-private partnership legal framework. Institutional change refers to a sustained change in policies, systems, or processes. The data come from 437 interventions—that is, advisory services and analytics and other nonlending, development policy loans, investment project financing, and Program-for-Results financing analyzed by the evaluation to identify outcomes.

Indicators measuring the World Bank’s procurement capacity strengthening in projects’ results frameworks are often outputs and are not fully achieved. The evaluation did not assess the results of procurement capacity strengthening ASA because of the weaknesses in reporting on results. In IPF, after at least four years of project implementation, 38 percent of indicators measuring procurement capacity strengthening are fully achieved (table 5.1). In closed projects, the level of achievement is just below 50 percent. Moreover, about 90 percent of the indicators in project results frameworks measuring procurement capacity strengthening are at the output level (for example, the number of people participating in training or the design or development of a plan or strategy) or at the intermediate outcomes level (for example, changes to procurement legislation or enhancements to procurement audits). About 9 percent of indicators measure institutional change related to the procurement principles, such as time reductions to complete procurement (which enhances efficiency).

Table 5.1. Achievement of Procurement Capacity Strengthening Indicators, Fiscal Years 2017–23 (percent)

|

Projects Implemented at Least Four Years |

Closed Projects |

|||

|

Level of Achievement of Indicators |

Intermediate outcome indicators |

Project development objective indicators |

Intermediate outcome indicators |

Project development objective indicators |

|

Achieved |

41 |

34 |

45 |

50 |

|

Evidence of progress |

29 |

36 |

19 |

32 |

|

Not achieved |

29 |

30 |

35 |

18 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The total number of procurement capacity strengthening indicators from investment project financing projects is 193. Indicators are those reported in the project results framework to measure procurement. Achieved = fully achieved at 100 percent or above; evidence of progress = indicators are above baseline but below the targeted change; not achieved = no positive change, or indicator dropped, or no data.

At the country level, measuring clients’ achievements toward the seven procurement principles is rare. About half of CPFs with procurement capacity strengthening activities measure progress toward the procurement principles. When they do, these typically include indicators on timeliness of procurement, which measures efficiency; use of e-procurement, which measures transparency and efficiency; and use of competitive bidding, which measures economy.

Opportunities to Optimize, Improve, and Better Recognize World Bank Staff Support in Projects

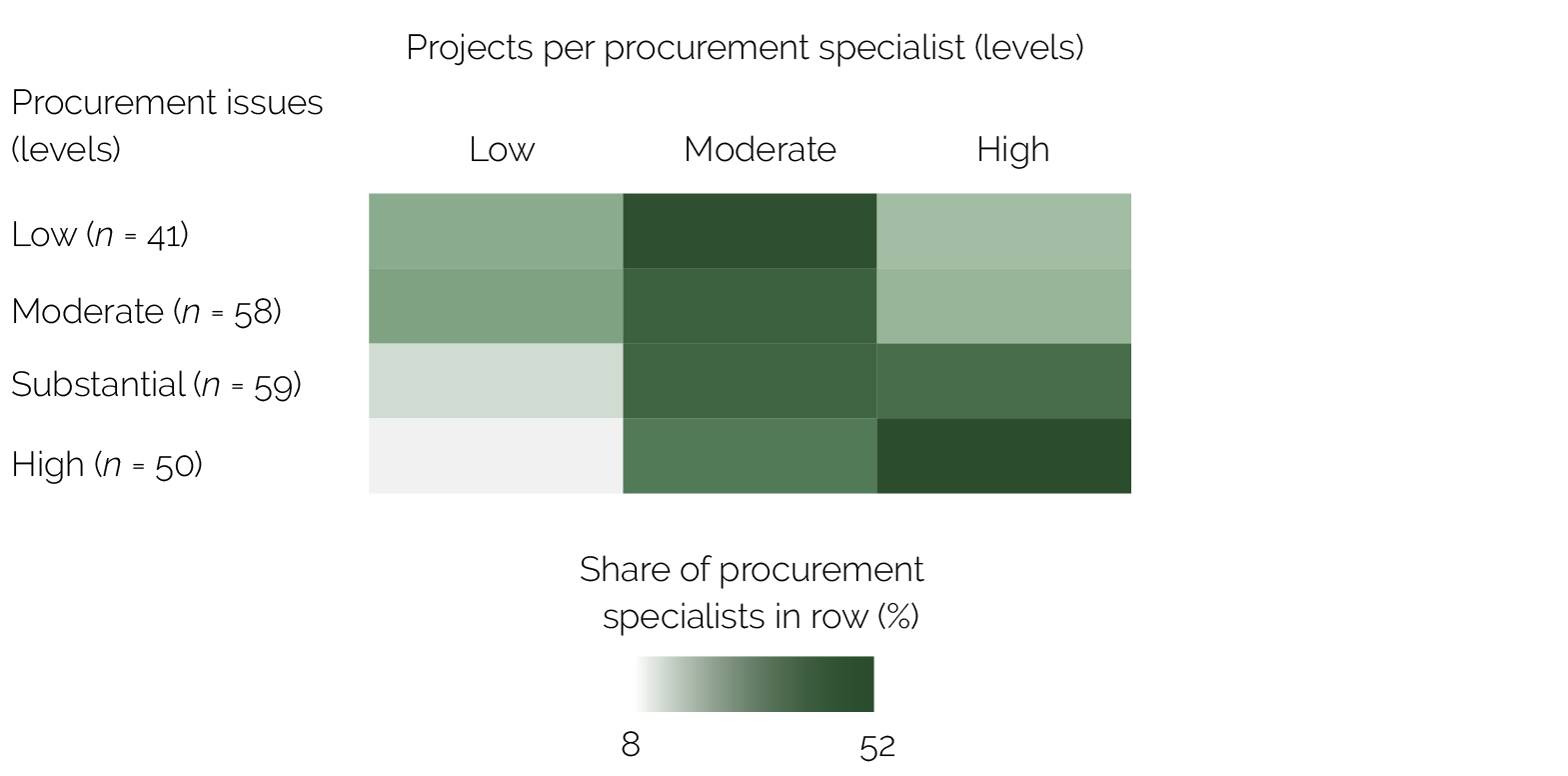

World Bank procurement staff have limited time, especially in Western and Central Africa and FCS countries, to support client procurement. Approximately 5 percent of procurement staff across Regions are responsible for 20 or more projects (appendix C). Workloads are heaviest in the Western and Central Africa Region (table 5.2). These countries also have the highest share of procurement activities and the highest share of HEIS in projects. In FCS countries, about half of procurement staff are responsible for 10 or more projects, 40 percent for 4–9 projects, and 16 percent for less than 4 projects. In countries with procurement staff who have higher project workloads, projects also encounter more procurement issues delaying their implementation (figure 5.5). During interviews, procurement staff note that they have little time to support clients because they have so many projects to support and because clients still require help with carrying out procurement processes subject to post review. According to one procurement staff in Africa, “The challenge is that if we complain that the project workload is too heavy, management is not responding because their concern is only procurement activities subject to prior review. So, sometimes I have no option than not helping the client.” In the survey, about 15 percent of procurement staff report that they have insufficient time to adequately support the client in applying the 2016 procurement framework.

Table 5.2. Procurement Staff Project Workload by Region

|

Region |

Projects (no.) |

Share of Projects (%) |

Procurement Staff per Project (team size) |

Projects per Procurement Staff (burden) |

Average Project Commitment (US$, millions) |

Overall Procurement Capacity |

Share of Procurement Activities per Region (%) |

Share of Projects with HEIS (%) |

|

AFW |

189 |

27 |

3 |

20 |

107 |

Low |

32 |

18 |

|

AFE |

135 |

19 |

2 |

12 |

162 |

Low |

22 |

12 |

|

SAR |

99 |

14 |

1 |

6 |

193 |

Low |

17 |

6 |

|

EAP |

95 |

13 |

2 |

10 |

105 |

High |

8 |

9 |

|

LAC |

88 |

12 |

2 |

7 |

118 |

High |

13 |

5 |

|

ECA |

78 |

11 |

2 |

9 |

106 |

Very high |

6 |

1 |

|

MENA |

28 |

4 |

2 |

6 |

148 |

Very low |

3 |

5 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Procurement staff per project (team size) is calculated by aggregating individual procurement staff within each project for 712 projects (1 global investment project financing is excluded) in the seven Regions, subject to procurement staff data available in Power BI. Similarly, projects per procurement staff (burden) are calculated by aggregating projects for each procurement staff assigned to them. Procurement staff includes ADM staff and non-ADM staff. Total procurement staff for the 712 projects is 220. ADM = accountability and decision-making; AFE = East and South Africa; AFW = Western and Central Africa; EAP = East Asia and Pacific; ECA = Europe and Central Asia; HEIS = hands-on expanded implementation support; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; MENA = Middle East and North Africa; SAR = South Asia.

Figure 5.5. Procurement Staff Support in Projects by Issues

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The figure shows shares of procurement specialists by levels of procurement issues in ISRs. Procurement specialists can be double counted across Regions, lending groups, and ISR issue levels because they can work across projects in different countries and in projects with different ISR issue levels. The levels of projects per procurement specialist are defined as follows: low = 1–3 projects, moderate = 4–9 projects, and high = 10–32 projects. The levels of issues in ISRs are as follows: low = one to less than three issues, moderate = three issues, substantial = more than three to six issues, and high = more than six to eight issues. The total number of procurement specialists in 713 projects is 165. ISR = Implementation Status and Results Report.

World Bank procurement staff have a mix of skills that can support clients, but many feel unprepared to help clients apply the reform’s new approaches. In the survey, about 60 percent of procurement staff note that they have received adequate training to support clients in applying the procurement framework, have access to colleagues who can support them, and consider the available guidance material suitable. Most procurement staff, especially those in higher grades and with more experience, agree that they have the experience to support clients in applying approaches incorporating quality (79 percent) and, to a lesser extent, sustainability (54 percent). TTLs have a less favorable opinion, with only about 38 percent believing that procurement staff have adequate knowledge to apply the reform’s new approaches (appendix G). About 65 percent of procurement staff have technical skills beyond procurement. This includes transport, urban planning, energy, and water and sanitation (appendix C). Although not all procurement staff might be ready individually to support clients in applying the reform’s new approaches, taking advantage of their collective skill mix through strategic allocation of teams to projects, change management, and training might bring the World Bank a long way.

Even fewer TTLs report that they have the necessary knowledge and training to help clients apply the reform’s new approaches. Only 34 percent of TTLs, especially those with more procurement training and knowledge, state that they have easy access to adequate training on all aspects of the procurement system. TTLs have taken limited procurement training: only 56 percent of TTLs state that they have taken two or more days of procurement training since FY16, and 33 percent state that their level of knowledge of the procurement system is moderate. Only 27 percent of TTLs report that they have the experience to help clients apply quality approaches, and 24 percent report that they have the experience to help apply sustainability approaches. These are mostly the TTLs who declare that they have substantial procurement knowledge. Lastly, 9 percent of the procurement staff believe that TTLs have adequate knowledge of the new approaches of the reform (appendix G).

There could be better recognition of World Bank procurement staff’s contributions to capacity strengthening. The case studies suggest smoother procurement processing in countries where World Bank procurement staff provide more day-to-day coaching. This support represents hidden procurement capacity strengthening because it is done through informal, unmeasured interactions with clients in projects. Capacity strengthening done by procurement staff also often gets little recognition from management. However, approximately one-third of World Bank procurement staff report spending one week per month helping clients strengthen country-level procurement systems (appendix G). This is an especially large amount of time considering that staff already have large project workloads, but it is often spread across many projects. Case studies show that task teams and clients value this support, although the time provided is often not enough for a single project. Tracking the capacity strengthening support and measuring its impact could raise awareness of the full benefits of capacity strengthening and added value for clients.

The World Bank’s short-term procurement training is rarely enough to meet the applied learning needs in World Bank–supported projects. In projects, World Bank procurement staff provide formal training, typically one to two days at least once a year, on general procurement rules, procedures, and systems or on specific procurement aspects, such as contract management and STEP. However, the case studies demonstrate that clients require more than this training to develop their practical procurement knowledge with more on-the-job or in-depth coaching. For example, the Federated States of Micronesia case study shows that formal training alone is insufficient to support practical procurement applications, and constant hands-on guidance is required. A client in Mali expresses strong appreciation for the learning they acquired through the World Bank specialist’s day-to-day support. Several clients in Africa also appreciate procurement clinics, such as those focused on how to prepare bidding documents. In other countries, such as Brazil, Kenya, and Nicaragua, the client and project team value regular procurement meetings among them to discuss and resolve issues as they arise.

Opportunities to Harness the Success of Hands-on Expanded Implementation Support and Knowledge Sharing

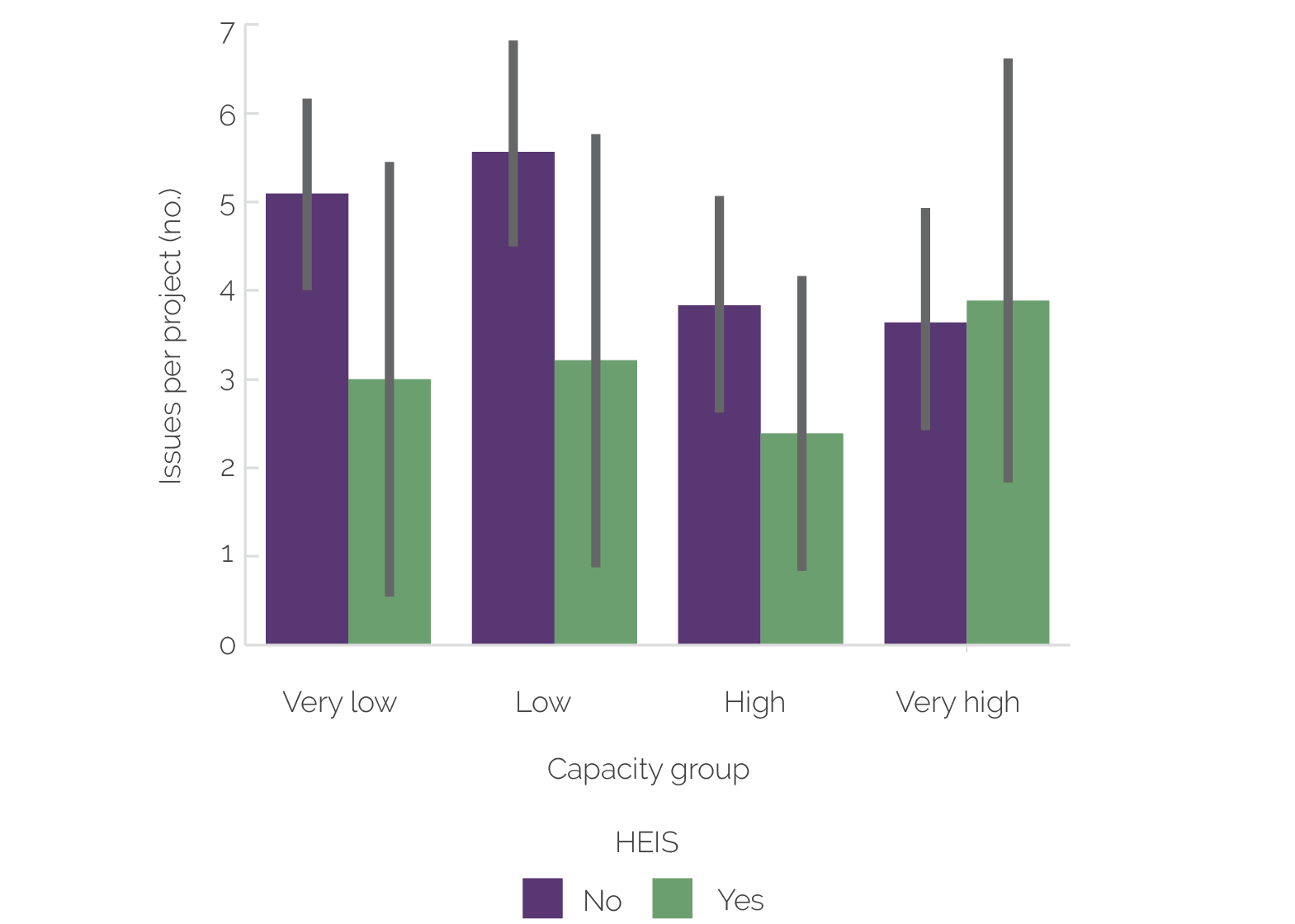

The World Bank usually uses HEIS in lower-capacity contexts to reduce procurement issues and improve project performance. The World Bank typically uses HEIS in FCS and low-capacity contexts. It can also use HEIS in higher-capacity contexts provided it will help IPFs (World Bank 2021c).5 Half of projects in countries with very low and low procurement capacity receive HEIS, whereas less than one-quarter of projects in countries with high and very high procurement capacity receive HEIS (appendixes C and E). Projects with HEIS also have fewer procurement issues reported in ISRs. This is true across country types and for most procurement issues, except logistic ones, such as supply chain delays. For example, figure 5.6 shows that HEIS reduces the number of reported procurement issues in countries with low and very low procurement capacity and is likely less helpful to reduce issues in higher-capacity countries. Similarly, HEIS has a strong benefit to reduce issues in FCS countries (appendix E). As detailed in chapters 2 and 4, projects with fewer procurement issues reported in ISRs have greater efficiency and higher procurement performance and project implementation ratings.

Figure 5.6. Hands-on Expanded Implementation Support and Reduction of Procurement Issues by Country Capacity Level

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: “Capacity group” refers to the group of countries with a specific procurement capacity level. The bar shows the average number of issues and the range. HEIS = hands-on expanded implementation support.

HEIS could better develop human resource capacity in projects. The World Bank designed HEIS to speed up procurement implementation by filling a project-level human resource gap. According to the interviews, in many projects, HEIS consultants prepare procurement documents and carry out procurement tasks themselves rather than coaching clients to do so. When this happens, it is a missed opportunity to develop local experience and skills because HEIS consultants are typically experienced and costly international consultants. For example, in Ghana, which offers a model for future HEIS, an experienced international procurement consultant provided HEIS through mentoring, training, and assistance to the country’s project implementation agencies. This led to effective on-the-job learning, according to the client. Similarly, in Liberia, instead of using HEIS and international consultants, the World Bank helped develop a pool of local procurement consultants. The availability of local experts allows projects to reduce costs and better understand local contextual implementation challenges. Moreover, clients often request HEIS late in project implementation to solve problems rather than prevent them or build capacity. For example, in a country in Southeast Asia, the World Bank provided HEIS to help the client prepare complex bidding documents after the project was delayed.

HEIS focuses on improving procurement efficiency but could do more to support the other reform principles. The case studies and portfolio data show that HEIS focuses on supporting efficiency improvements in projects. The same evidence suggests that the World Bank typically does not use HEIS to foster greater levels of innovation. In fact, projects with and without HEIS have similar levels of innovation, and projects with HEIS use fewer innovative open market approaches (appendix C). About 9 percent of projects that effectively achieve economy principles—such as improved quality, competition, and sustainability—receive HEIS.

Knowledge sharing could be better leveraged to help clients carry out procurement in World Bank–supported projects. Procurement knowledge sharing may take place through informal sharing of procurement documents, such as terms of reference and technical specifications, among task teams. However, the World Bank lacks a good knowledge management system and a repository of well-executed documents that might be informative for other task teams and clients. According to the interviews, clients have even less access to World Bank procurement knowledge because of the lack of formal knowledge transfer structures. In FY17–23, about 5 percent of the World Bank’s procurement capacity strengthening (figure 5.4) included support for regional procurement networks and global initiatives that facilitate collaboration. The case studies show that day-to-day knowledge exchange across clients in World Bank–supported projects could help solve day-to-day problems. For example, in Mali, the clients’ procurement specialists in project implementation units created a chat group to help solve procurement problems. In Togo, World Bank procurement staff formed an informal network for clients to share experiences through WhatsApp or meetings and support each other in solving procurement problems.

Knowledge sharing helps clients adopt less familiar procurement approaches and carry them out faster. For example, the World Bank shared examples of bidding documents with clients during COVID-19, which helped clients learn how to properly procure urgent supplies, such as medical equipment (World Bank 2022c). The case studies show that sharing technical specifications for procurement activities helps speed up quality procurement because clients do not have to prepare these specifications from the start. In Bangladesh, study tours helped the client’s project implementation staff learn to apply a procurement smartphone application and management information system.

- The Independent Evaluation Group’s 2014 procurement evaluation recommends that the World Bank develop a strategic and long-term approach to procurement capacity building in client countries. The evaluation also finds that a myriad of procurement capacity strengthening was undertaken for client countries but that strategic planning for procurement capacity strengthening is absent and efforts have been fragmented. Therefore, the evaluation recommends developing a strategic and long-term approach to procurement capacity strengthening that is integrated into the World Bank’s country strategy (World Bank 2014).

- The Independent Evaluation Group’s 2014 procurement evaluation finds that 95 percent of Country Assistance Strategies reviewed made some reference to procurement and 43 percent reviewed include procurement outcomes or monitoring indicators (World Bank 2014).

- Before the 2016 reform, the World Bank conducted country procurement assessment reports that are no longer used.

- Twenty-five countries that received support in FY10–16 did not receive support in the period since the reform (that is, there was no continuity).

- Hands-on expanded implementation support can be used “if the [World] Bank determines that this support is useful to help the Borrower [client] achieve the development objectives and outcomes of an [investment project financing] operation” (World Bank 2021c, 3).