Making Procurement Work Better

Chapter 4 | Improving Procurement Fit for Purpose and Value for Money

Highlights

The 2016 reform introduced flexibilities that allow clients to tailor procurements to their needs and maximize value for money. However, only about 30 percent of projects achieve this customization. Few clients and task team leaders have the knowledge to do this.

Clients who apply the procurement principles are more likely to achieve satisfactory procurement performance and project implementation ratings, suggesting that the logic of the World Bank’s procurement reform is sound.

Projects that process procurement activities early in project implementation and with the support of experienced procurement specialists have fewer procurement issues, better performance, and better value for money regardless of country capacity. However, the largest proportion of signed procurements happen in year three, near the end of a project, limiting what a project can achieve. Projects with satisfactory implementation ratings had, on average, 40 percent of their procurement activities signed by the end of the first year.

The client’s procurement experience, familiarity with the procurement methods, history of procurement issues, procurement risk, and procurement start times can be predictive of a project’s eventual success. Using this information to optimize procurement support can enhance value for money.

Strategic procurement planning works when clients and World Bank technical and procurement staff collaborate. However, less than 20 percent of projects use their procurement strategies.

The World Bank advanced its procurement data analytics, but these lack benchmarks that would help assess procurement achievements across the principles, inform decision-making at project and portfolio levels, and optimally target support to projects.

The World Bank’s procurement risk analyses could be streamlined and pay more attention to collaboratively assessing and mitigating the full spectrum of risks, including those related to project development objectives.

This chapter assesses how the World Bank has improved procurement fit for purpose and value for money. Value for money is the procurement principle that others feed into. Achieving high value for money requires the optimal combination of financial and nonfinancial benefits in any procurement.1 Fit for purpose refers to how well a procurement approach fits the purpose of the procurement and its project—in other words, the extent to which clients customize procurement approaches to the country context and project needs to help achieve value for money. The chapter looks at the World Bank’s success at tailoring for fit for purpose and combining procurement principles to optimize value for money, the benefits of starting procurement early in project implementation, the value from PPSDs, and the use of procurement data analytics and risk assessments to inform procurement-related decisions. The chapter concludes that the World Bank achieves high value for money when it applies the procurement principles; however, procurement strategy, risk analysis, and data analytics could better support decision-making for better procurement performance.

Application of the Procurement Principles Leading to Better Performance

A fit-for-purpose approach helps clients customize the procurement principles to meet a particular project’s needs and enhance project implementation. This, in turn, helps clients achieve these principles in projects and ultimately promotes value for money and enhances project implementation. This finding is reinforced by the analysis detailed in appendix C. However, in the case studies, only about 30 percent of projects show a high customization of procurement. For example, in a Bangladesh local governance project, the client tailored their procurement of decentralized small works to the country’s low-capacity context. Customizations included recruiting audit firms to oversee procurement, using an application and geotagging to monitor subnational procurement activities, assigning local coordinators to oversee activities, and training local entities in procurement. The client organized prebid meetings with potential suppliers to understand their capabilities and adapt the procurement’s technical specifications accordingly. In a Lesotho COVID-19 emergency health project, the World Bank helped the client develop a fast and simple procurement approach to ease the procurement process. This approach included requests for quotations, standard procurement documents, and a limited number of qualified suppliers. In each of these examples, customization required trade-offs. For example, the Lesotho project chose simple instead of complex procurement approaches and a limited selection approach instead of an open market approach.

Tailoring procurements to country and project needs requires a sophisticated knowledge of procurement approaches, which TTLs and clients rarely possess. In the survey, about 80 percent of World Bank procurement staff state that the World Bank’s procurement system works well and that procurement approaches are flexible enough to meet country and client needs. Conversely, 36 percent of TTLs report that the procurement system works well, and about 25 percent of TTLs consider the procurement approaches to be flexible enough. Only 14 percent of TTLs state that the flexibility in the procurement system leads clients to seek innovative solutions (appendix G). Thus, World Bank procurement staff and TTLs lack the same understanding of the World Bank’s procurement system or its flexibilities. In the survey, about 25 percent of TTLs report that they had the necessary experience to advise clients on the reform’s less common procurement approaches, such as sustainable procurement. The case studies also indicate that most TTLs and clients lack the know-how to help clients successfully customize procurement in projects (for task teams, the case study–based estimate is that less than 10 percent have adequate knowledge of procurement planning).

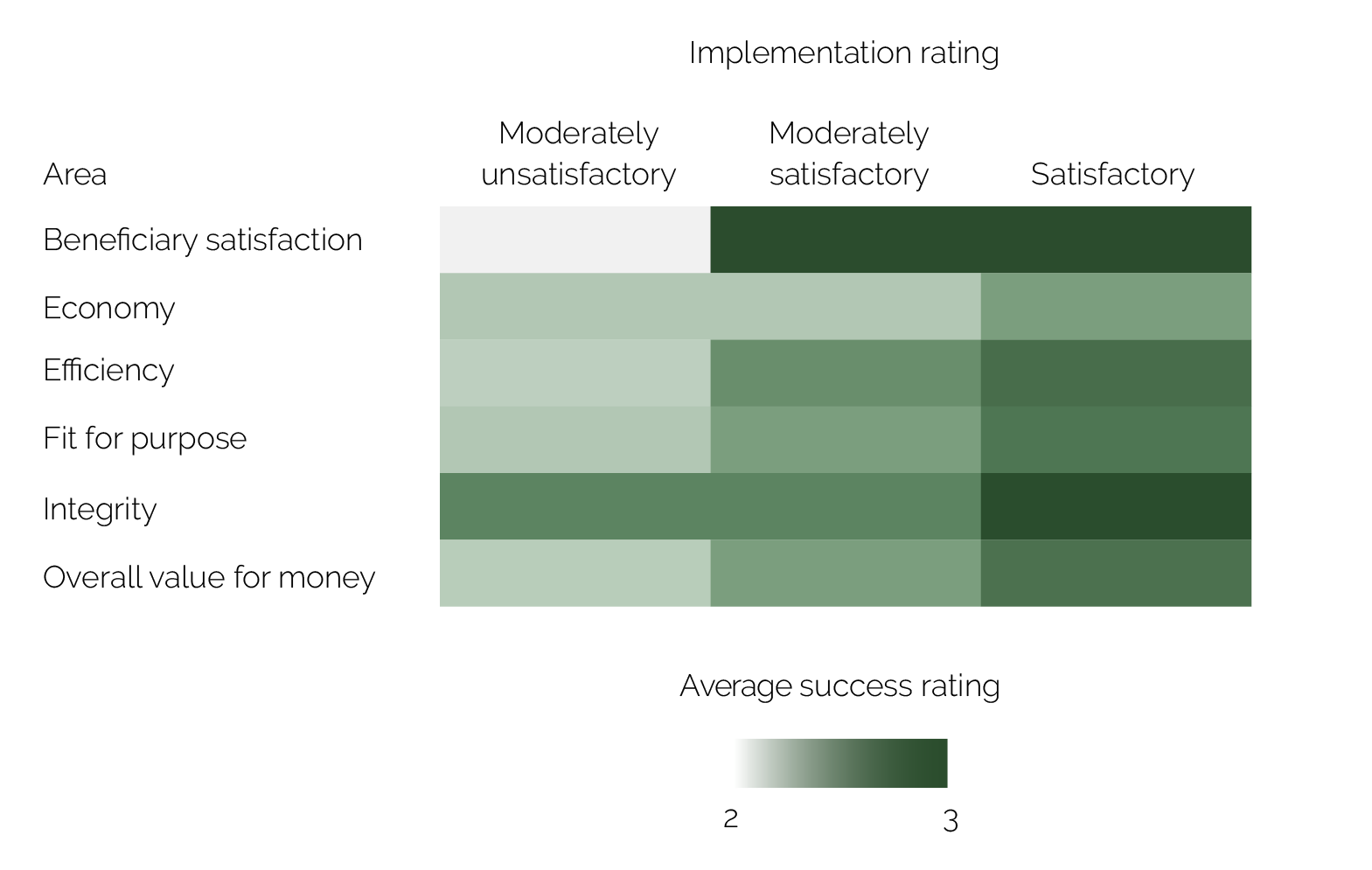

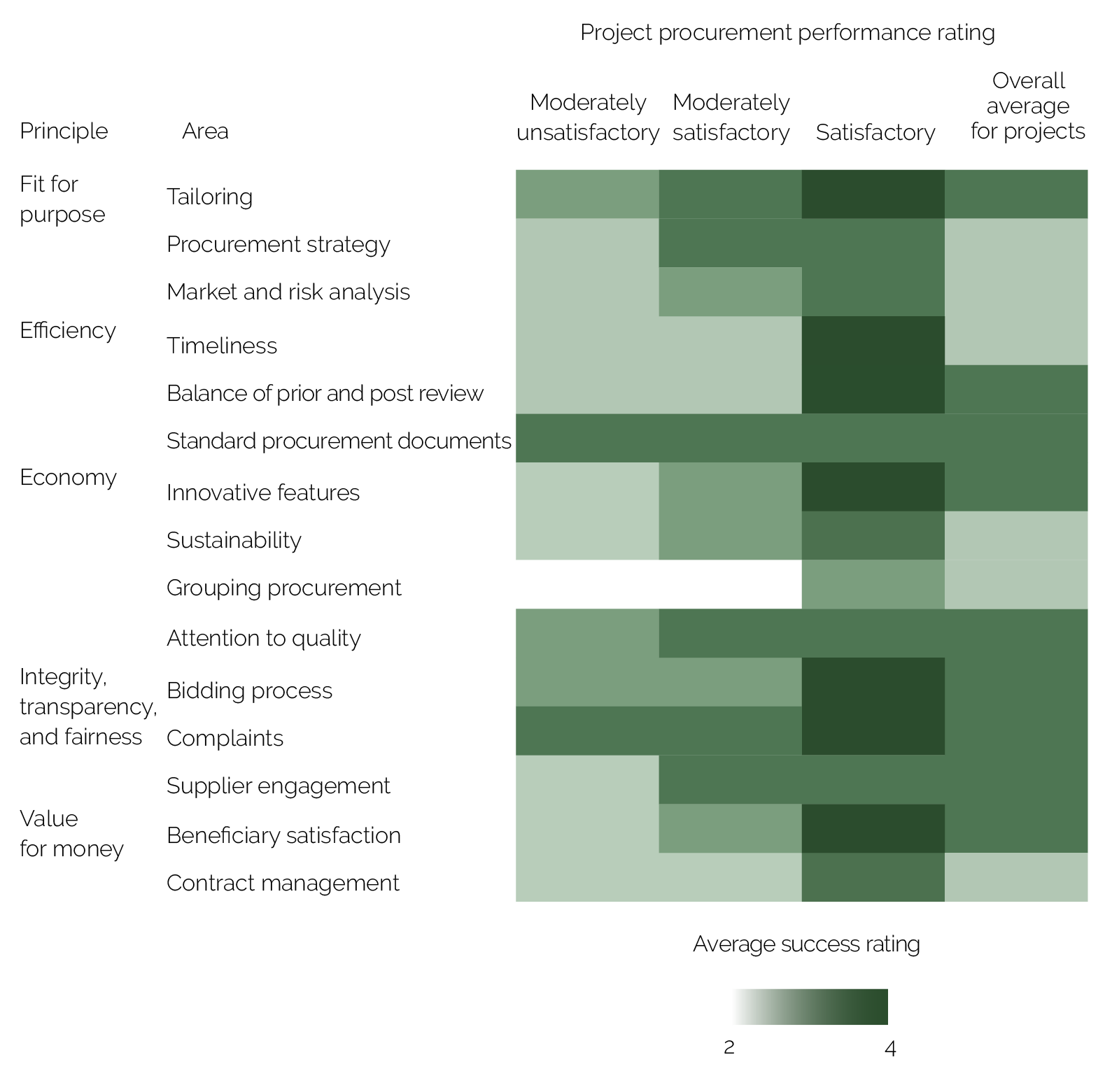

Clients who successfully apply the procurement principles are more likely to achieve satisfactory project implementation ratings. Figure 4.1 shows that projects that address the principles of efficiency, economy, integrity (which is combined with the principles of fairness and transparency in the visual), fit for purpose, and value for money and that report that procurement activities helped beneficiaries often had satisfactory or higher implementation ratings (see value-for-money indicators in appendix B). Project implementation ratings and project procurement performance ratings are also positively correlated. Projects that apply the procurement principles also report fewer procurement issues in ISRs. Figure 4.2 shows the relationship between procurement performance ratings and value for money for all seven principles for a random sample of 74 project case studies, stratified by procurement performance ratings. Figure 4.2 also breaks down areas of each procurement principle, such as tailoring and strategizing to customize procurement approaches in a project and use of market analysis and availability of experienced support to help carry out procurement (which, according to the case studies, are important for fit-for-purpose procurement). This suggests that the logic of the World Bank’s procurement reform is sound: applying the procurement principles supports project implementation and contributes to a project’s development outcomes.

Figure 4.1. Projects’ Achievement of Procurement Principles by Implementation Rating

Source: Independent Evaluation Group case study analysis.

Note: The figure shows average achievements of procurement principles for all sampled case study projects based on the ratings given in each case study analysis (appendix F). The areas reviewed to assess each principle align with the evaluation framework. For each principle, the extent to which the project is successful was assessed and rated on a scale of 1 to 4: 1 is not successful, 2 shows some aspects of success but could improve, 3 is mostly successful, and 4 is highly successful. “Integrity” refers to integrity, fairness, and transparency.

Figure 4.2. Projects’ Achievement of Procurement Principles by Procurement Rating

Source: Independent Evaluation Group case study analysis.

Note: The figure shows the average achievements of procurement principles for sampled case study projects based on the ratings given in each case study analysis (appendix F). The areas reviewed to assess each principle align with the evaluation framework. For each principle, the extent to which the project is successful was assessed and rated on a scale of 1 to 4: 1 is not successful, 2 shows some aspects of success but could improve, 3 is mostly successful, and 4 is highly successful. “Integrity” refers to integrity, fairness, and transparency. Moderately unsatisfactory, moderately satisfactory, and satisfactory are the project procurement performance ratings. “Overall” refers to the average rating for achieving each area of the procurement principle in the case studies.

Case studies show that tracking the procurement principles in the portfolio can help projects achieve value for money. Projects achieve fit for purpose through the collaborative engagement of clients, TTLs, and World Bank procurement staff to customize procurements, plan capacity strengthening, and identify the areas that need market analyses. Projects achieve efficiency by starting procurement early and quickly addressing procurement issues as they arise, such as during the evaluation of bids stage. Projects achieve economy by engaging qualified suppliers and applying innovative procurement approaches to address project needs. Projects attain integrity, transparency, and fairness through frequent interactions between the client and World Bank staff to ensure the quality of post review procurements, timely handling of complaints, and flagging of important procurement activities as higher risk to ensure that clients pay closer attention to them. Similarly, tracking and monitoring procurement by the client in collaboration with the task team and World Bank procurement specialists help clients make proactive procurement decisions to support project implementation and deliver on the seven principles.

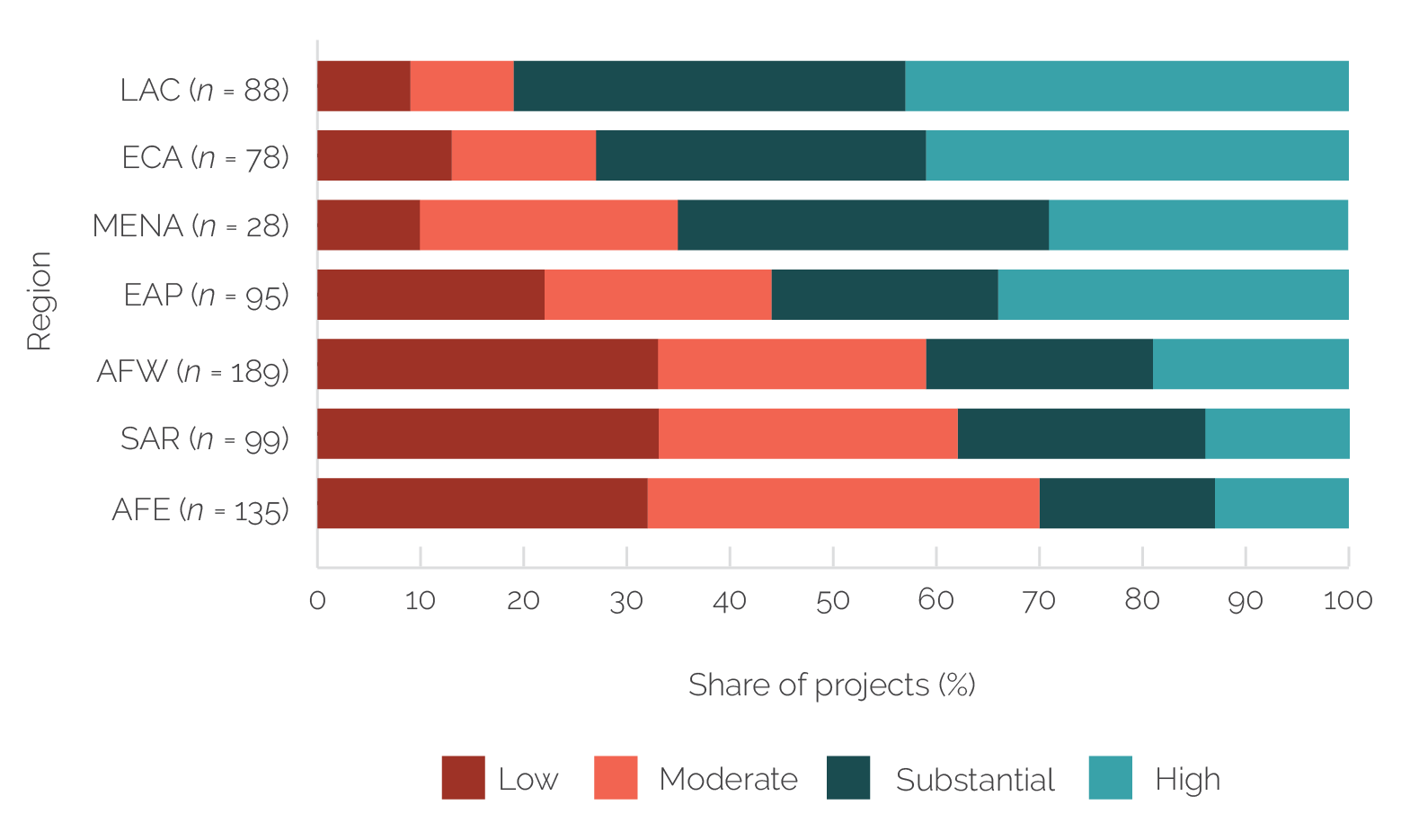

Procurement support can improve the value for money of procurement in low-capacity countries.2 Figure 4.3 shows that the share of projects with the highest value-for-money scores is in Latin America and the Caribbean, followed by Europe and Central Asia. By contrast, Eastern and Southern Africa, South Asia, and Western and Central Africa have the lowest value for money. Achieving higher value for money is more likely in IBRD countries than in IDA and FCS countries. Western and Central Africa and the Middle East and North Africa are Regions with lower procurement capacities. The country situation analysis suggests that countries with lower procurement capacity can achieve high value for money when there is experienced procurement support in the project (appendix E). This support could be provided by World Bank procurement specialists, HEIS, or other tools.

Figure 4.3. Average Project Value-for-Money Scores by Region

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The figure shows the share of projects within Regions by level of value-for-money composite score (appendix C). The levels are determined based on the data quartiles. The composite indicator score is estimated by combining the composite indicators of project achievement of the principles of efficiency; economy; integrity, fairness, and transparency; and fit for purpose. The total number of projects is 713. AFE = Eastern and Southern Africa; AFW = Western and Central Africa; EAP = East Asia and Pacific; ECA = Europe and Central Asia; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; MENA = Middle East and North Africa; SAR = South Asia.

Starting Procurement Early to Facilitate Project Implementation

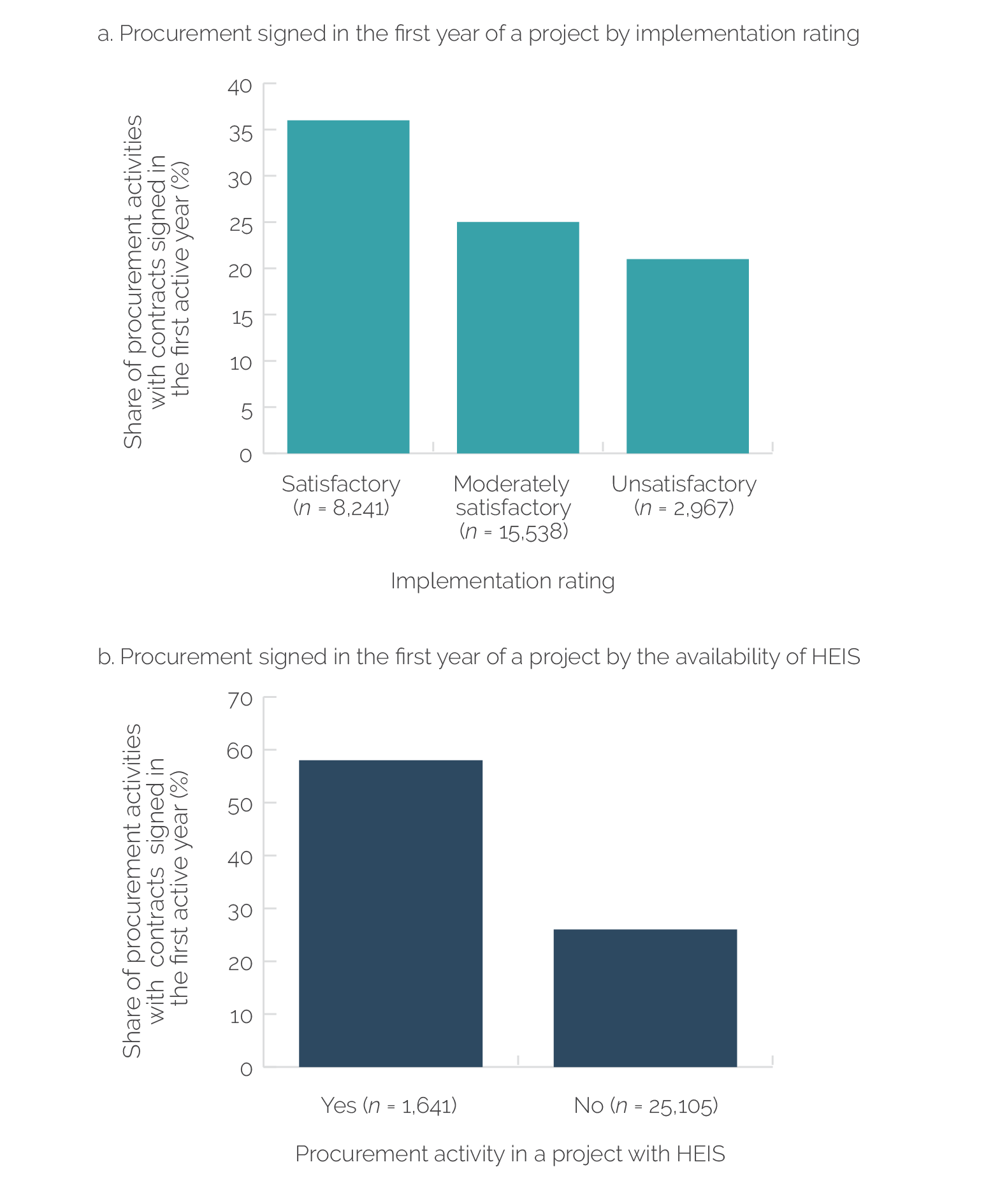

Projects that process procurement activities early tend to have better implementation performance and higher value for money. Projects with satisfactory implementation ratings have a higher proportion of procurements with signed contracts in the first year of implementation (figure 4.4, panel a). This proportion was even higher for projects supported by HEIS (figure 4.4, panel b). The evaluation’s country situation analysis indicates that lower project implementation performance ratings are associated with procurement delays early in project implementation. Projects with substantial to high value for money have about one-third of contracts signed within the first year of implementation and report fewer procurement issues in ISRs.

Figure 4.4. Signed Contracts in the First Year by Project Ratings and Hands-on Expanded Implementation Support

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Panel a shows the proportion of procurement activities with contracts signed in the first active year by implementation rating. Panel b shows the proportion of procurement activities with contracts signed in the first active year by the availability of HEIS. Projects with highly satisfactory implementation ratings are combined with those that are satisfactory. Projects with highly unsatisfactory or moderately unsatisfactory implementation ratings are combined with projects that are unsatisfactory. The total number of procurement activities with signed contracts in 617 projects is 26,746. HEIS = hands-on expanded implementation support.

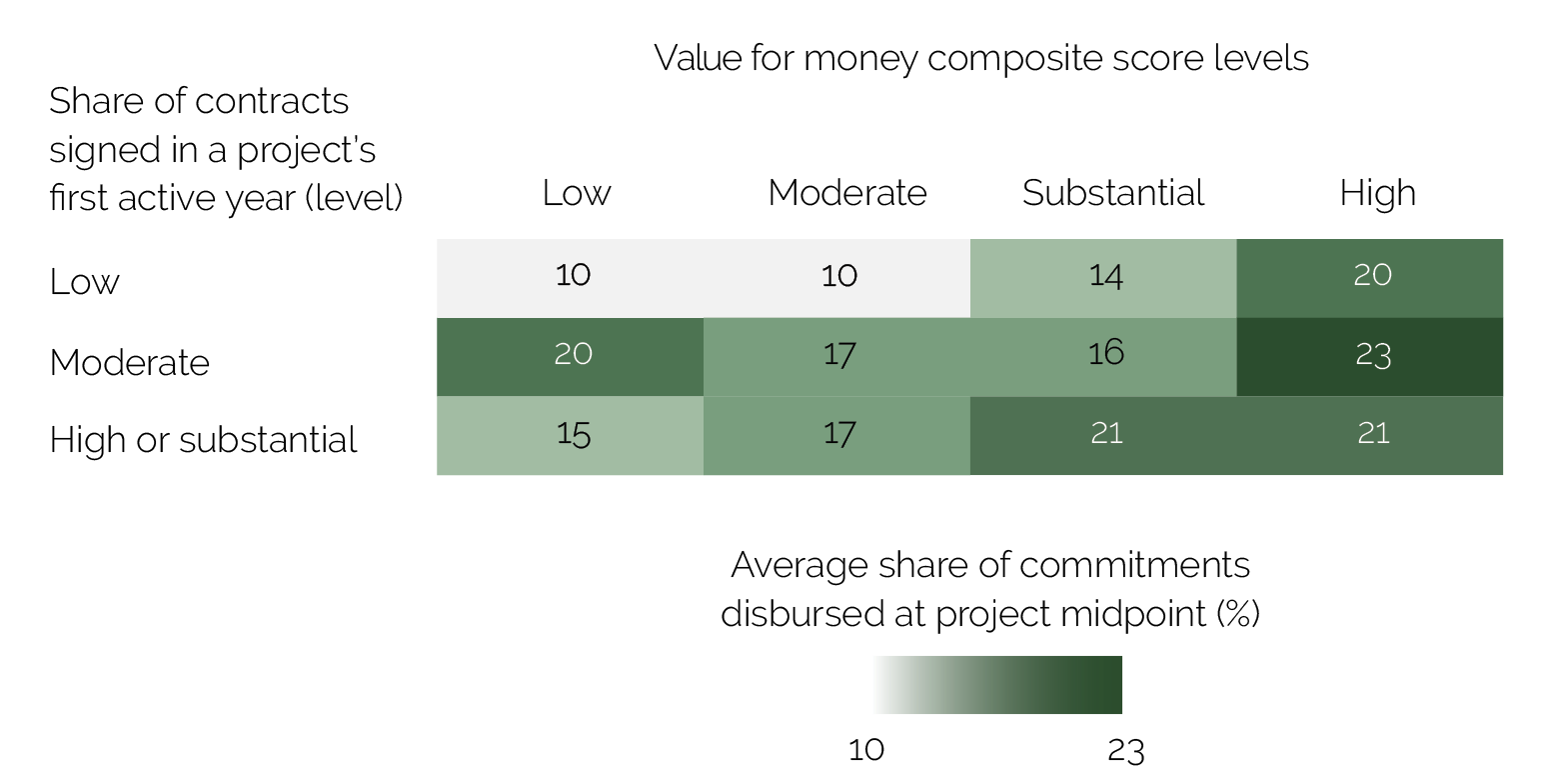

The late start of procurement activities often delays project disbursement to activities that are key to project development objectives. Signing key contracts in the first year of a project helps ensure that a higher share of project financing can be disbursed to beneficiaries by the project midpoint and that the project can bring greater value for money (figure 4.5). Starting procurement late can, conversely, delay disbursement of financing for activities toward the project’s outcomes. Across projects, STEP analyses show that the largest proportion of signed procurements occur in year three, near the end of a project, and contracts take, on average, several years to carry out (appendix C). The case studies provide several examples demonstrating that the late start of activities affects the achievement of key activities for project development outcomes. In Malawi, COVID-19 restrictions delayed the project’s procurement of an engineer, leading to delays in other activities important for the project outcomes. In a Republic of Congo public sector reform project, the client’s inexperience slowed procurement activities and affected project implementation of activities key for project outcomes. Such projects may pick up speed before closing, but procurement delays early on in projects consistently reduce the time for implementing project activities to achieve the intended outcomes for beneficiaries. For example, early procurement delays in a nutrition project in Benin reduced the available time to implement grant activities, thereby limiting the number of districts that received nutrition services.

Figure 4.5. Signed Contracts in the First Year by Value for Money and Commitments at Project Midpoint

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The figure shows the composite indicator score estimating value for money for projects in the evaluation portfolio from fiscal year 2017 to fiscal year 2023 (appendix C). The levels are determined based on the data quartiles. The composite indicator score is estimated by combining the composite indicators of project achievement of the principles of efficiency; economy; integrity, fairness, and transparency; and fit for purpose. The indicator is compared with the share of signed contracts in a project’s first active year and the share of commitments disbursed at the project midpoint.

More experienced client procurement specialists in countries could help ensure that procurement activities start early and maximize value for money. As described in chapter 2, one of the main challenges affecting project outcomes is the lack of access to experienced procurement specialists in the project early in implementation. In Bangladesh, the client established the procurement coordination unit early in the project. As a result, the unit acquired procurement and subject matter specialists to prepare technical specifications at the beginning of the project timeline. In some projects, clients share procurement specialists from existing projects to support new projects. However, this also slows the implementation of the original projects because the specialist now has too many projects at the same time to meet the increased workload. A more promising model for clients is to set up central procurement support that projects can draw from. The evaluation uncovered examples of this model in Albania, Serbia, and South Pacific countries. Other countries, such as Liberia, use in-country procurement training programs to build their in-house procurement capacity. Other possibilities include using grants to hire procurement specialists or soliciting HEIS from the World Bank.

Strategic Procurement Planning, Collaboration, and Incentives

World Bank staff and clients recognize the value of strategic planning in procurement. Case studies show that World Bank staff and clients recognize the importance of strategic procurement planning and how it can help identify procurement solutions that contribute to a project’s development objective, design suitable approaches for such activities, define areas for capacity strengthening, and develop means to better engage the market, among other benefits. The PPSD, introduced with the 2016 reform, is a methodology for strategic procurement planning to help clients customize an optimum procurement approach for a given project. The World Bank can also use client PPSDs to flag areas for management that would benefit from procurement support (World Bank 2018b).

Procurement strategic planning could be simplified at the country level and made more useful for projects. In practice, the PPSD is often a generic document with similar content across many projects. Moreover, case studies show that clients rarely use PPSDs. TTLs and clients often consider the PPSD as a compliance task and as not providing practical inputs for procurement planning, but procurement staff view the PPSD as more useful compared with TTLs. In the survey, about 60 percent of procurement staff (but 30 percent of TTLs) report that PPSDs help design procurement approaches that are fit for purpose. In the case studies, some TTLs recommend simplifying and integrating PPSD into project procurement plans that set out the project’s procurement activities, approaches, and timing, among others. Clients actively use these plans and update them, on average, about 30 times during a project; therefore, integrating strategic procurement planning into them could immediately make it more relevant. However, clients want the format of the procurement plan to be easier to read and compatible with their own database, such that they can update it offline and use it as a tool for monitoring. The case studies also indicate that having a procurement strategy at the country level could help optimize the World Bank’s support of projects because procurement issues often repeat across projects in a country.

Project procurement strategies are impractical without client ownership and collaboration. The main challenge is the limited client involvement in preparing and updating the PPSD (or “ownership”) in their development. In the survey, about 20 percent of procurement staff and TTLs report that clients own their PPSDs and substantively contribute to their development. Clients often hire consultants to prepare the PPSD before the project staff responsible for implementation decisions are on board. A World Bank review of PPSDs emphasizes the importance of genuine client ownership of the PPSD that helps enhance project implementation (World Bank 2018b). The case studies demonstrate that ownership requires collaborative engagement to strategize procurement and that the client develops and updates the PPSD. For example, in Bangladesh, the project coordination unit, with World Bank procurement staff support, adopted a PPSD to customize procurement activities to the project, and the client updated it during implementation. In a cash transfer project in Djibouti, the PPSD was developed by the client and was useful to forecast procurement challenges and identify mitigation actions. Similarly, in Nigeria, the government and World Bank jointly developed a PPSD for an electrification project that included comprehensive market and risk analyses and a review of procurement options and was updated and used by the project.

The World Bank could improve incentives for procurement staff to support clients’ strategic procurement planning. As further detailed in chapter 5, World Bank procurement specialists have heavy project workloads and are encouraged to support higher-value procurement activities, such as large infrastructure contracts. They provide other support, such as strategic procurement planning, when their work schedule permits. According to the case studies, World Bank procurement staff rarely collaborate with the client and TTL to carry out strategic procurement planning. A World Bank review of PPSDs emphasizes the opportunity to adjust work program incentives to reward procurement staff for collaborating with project teams to strategize their procurement (World Bank 2018b).

Leveraging Advances in Data Analytics for Procurement Performance

Certain project characteristics can predict which projects are likely to encounter procurement issues and help the World Bank target preventative support. These characteristics include a client’s procurement experience, history of procurement issues, procurement risk levels, a client’s familiarity with procurement approaches, and progress of procurement activities early in the first year of the project. The evaluation’s analysis of country procurement situations and the project portfolio uncovers several common characteristics that projects with procurement issues share (appendix E). These projects are in low-capacity countries that lack experienced client procurement staff. These projects also tend to take on unfamiliar procurement approaches without proper support or guidance. Projects with higher-risk ratings also portend future procurement challenges. Furthermore, countries that have previously encountered procurement issues, as reported in ISRs, are likely to encounter similar issues in future projects. In addition, projects with a limited number of contracts signed in the first year of implementation are likely to face implementation delays in procurement. Understanding these factors and identifying them early can help the World Bank predict the likelihood of procurement issues in the projects and target preventative support. This prediction could then help allocate the World Bank’s procurement support to projects that will likely face more challenges.

The World Bank’s procurement data analytics have advanced since the reform, but they could be better used to increase value for money. The reform’s introduction of STEP helped the World Bank take a step forward in tracking procurement data and making it readily available to staff and clients and partially available to the public. However, the data collected from STEP are still fragmented in different databases. The data could be enhanced to offer information that staff and clients can easily use for strategic procurement decisions (which, in turn, would lead to improvements in procurement value for money and project implementation). According to the interviews, World Bank staff and clients want data analytics to help them make project-level decisions. For example, they call for indicators that allow them to assess their project’s procurement principles against other projects in the portfolio.

The World Bank’s procurement dashboards could improve with indicators on the procurement principles and clear benchmarks. This would help assess performance and inform decisions at different levels, such as for clients implementing projects, procurement staff and TTLs supporting projects, and managers overseeing the portfolio. The World Bank has developed procurement dashboards and a mobile application for World Bank staff to monitor projects. These dashboards provide much information on efficiency, such as average timelines for procurement activities, but lack data on other principles and could be improved to measure indicators against benchmarks or targets. Thus, World Bank TTLs, procurement staff, country managers, and clients are unable to gauge, for example, whether procurement is taking longer than expected and whether procurement bottlenecks are adding delays and to decide how they can improve the value for money of procurement in the project. Expanding data analytics to include indicators on all procurement principles and measuring them against benchmarks would help teams flag potential problems and devise mitigation actions that can help projects achieve better procurement performance and value for money. Box 4.1 details how the World Bank could enhance its procurement analytics.

Box 4.1. Opportunities to Enhance Procurement Analytics

Benchmarks to understand procurement performance. Current World Bank dashboards focus on averages—number of turnaround days, number of activities, and cost, among others—and could be improved to provide benchmarks and targets for comparison. Large performance differences across groups skew the averages. Clear value distributions could help define very good, good, weak, or very weak achievements for an indicator and provide an easy reference to determine if a procurement activity is in an acceptable range of performance.

Indicators to trigger alerts for remedial action. Dashboards could use data mining and other tools to flag risks, such as projects that have taken a long time to sign their first contracts and projects with procurement post review reports that show procurement problems.

Indicators to assess the seven procurement principles. Current World Bank dashboards emphasize timeliness, process delays, and the proportion of post review procurement in a project. Indicators could track outcomes toward other principles, for example, by monitoring the quality of competition, indicators for different types of sustainable procurement coordinating with the monitoring of the World Bank’s Environmental and Social Framework, the quality and frequency of post review procurement, client feedback on the use of procurement strategies, the performance of hands-on expanded implementation support, and the frequency and timeliness of complaint resolutions (appendix B).

Indicators to assess value for money of projects and the portfolio. Measures to assess value for money could use a composite indicator at the project and portfolio levels that looks at the combined achievement of the procurement principles in a project.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group review of World Bank procurement measurement.

The Governance Global Practice, regions, and Operations Policy and Country Services could use data analytics to adaptively monitor the reform’s implementation. World Bank management could use the available procurement data or analyses of procurement achievements to adjust the 2016 procurement reform implementation and rollout to support projects. This could include systematically monitoring reform activities, such as the use of procurement approaches to address quality and sustainability or repeated procurement issues or bottlenecks that jeopardize procurement in projects. Better use of data could facilitate strategic decisions and knowledge sharing on what works and does not and help identify ways to support procurement staff to advance the 2016 reform actions.

Improvement of Procurement Risk Analysis and Mitigation

Project-level procurement risk assessments could be simplified by reducing their frequency and emphasizing data analytics of risks. Procurement staff biannually conduct a project risk assessment using the Procurement Risk Assessment and Management System (PRAMS). PRAMS is meant to guide decisions to mitigate procurement risks in a project (World Bank 2019).3 TTLs see PRAMS as a valuable baseline assessment to inform procurement in the project when done comprehensively. However, these repeat assessments can take several days to complete, rarely yield new information, and often miss details on post review procurement and other risks related to complexity, innovation, development objectives, procurement issues, and capacity. The case studies and the portfolio analysis show that risk assessment ratings rarely change during implementation and vary in how risk is assessed across projects. Moreover, risk analysis findings are not typically used to inform procurement activity design or mitigation actions. The highest-value procurements typically have the highest risk. IEG’s 2014 procurement evaluation also underscores the limited value of repeat assessment (World Bank 2014). As such, in interviews, World Bank staff indicated that PRAMS would improve by reducing the frequency of assessments and replacing them with a more rigorous baseline assessment early in project implementation. The assessment could be complemented by real-time data analytics of procurement activities in projects to identify risks (such as related to procurement issues, delays, competitive processes, and post review oversight) throughout a project. In addition, there could be more emphasis on tracking the success of mitigation actions.

Procurement risk assessments could better emphasize the importance of procurement activities for achieving project development objectives. The case studies reveal that certain procurement activities can strongly influence project outcomes. For example, delays in hiring a consultant to prepare for subsequent procurement activities might critically delay these activities and prevent the project from achieving the full scale of planned results. The case studies also demonstrate that project-level assessments in PRAMS and PPSD do not consistently consider the risk that procurement activities pose to project development objectives. The Asian Development Bank’s recent procurement evaluation reports a similar finding (ADB 2023).

Procurement risk assessments could be improved by considering the full spectrum of risks at the procurement activity level. The case studies show that task teams and clients benefit from the review of each important procurement activity to set a risk level for it in the procurement plan. This might highlight activities that are more complex from the client’s perspective; have greater market uncertainties; face risks in terms of cost, quality, and delivery time; and are important to the project’s development objective. Thus far, the risk analyses have heavily focused on the monetary value of the procurement, missing other risk elements of concern in projects. For example, in Burkina Faso, the World Bank procurement specialist and task team collaborated to assess activity risks. This helped customize their support and advise the client on which procurements required closer monitoring.

Precision, client involvement, and strong monitoring could help implement procurement risk mitigation actions. PRAMS often prescribes only generic mitigation actions, such as providing more procurement training to clients. However, as evidenced from the case studies, projects require concrete actions to address procurement risks. For example, in Albania and Pakistan, risk assessments identified concrete actions to improve procurement. Moreover, the case studies show that when the task team and clients work together to identify concrete mitigation actions, the actions are more likely to be effective. Another challenge identified in this evaluation is that PPRs, PRAMS, and PPSDs all identify separate mitigation actions and that their implementation is not well tracked. Hence, more concrete, better-monitored mitigation actions in a single place might lead to better risk mitigation—the main purpose of PRAMS.

- In its 2016 procurement guidance on value for money, the World Bank defines it as the effective, efficient, and economic use of resources, which requires the evaluation of relevant costs and benefits, along with an assessment of risks, and of nonprice attributes and life cycle costs, as appropriate. Price alone may not necessarily represent value for money.

- Value for money is estimated using a composite indicator of how well projects achieve aspects of each of the principles. The composite is estimated for the active portfolio by combining average indicators of project achievement of the principles (efficiency; economy; integrity, fairness, and transparency; and fit for purpose) using principal components analysis (appendix C). The approach provides a score for each project by estimating the success of procurement indicators. The indicators selected for the composite are based on guidance from the literature (appendix B). The efficiency indicators in the composite are the amount of procurement signed in the first year of a project, turnaround timeline for processing activities, amount of post review procurement in the project, and average number of delay days reported in data on electronic system transactions for procurement activities in the project. The economy indicators for the composite consider the use of open market approaches, the use of innovative or nontraditional procurement approaches, and the success of bidding processes. The integrity, transparency, and fairness indicators consider the integrity risk rating of projects, risk ratings for procurement activities, availability of a procurement post review report in the project’s previous fiscal year, timelines to resolve complaints, and duration of standstill periods. The composite also considers fit for purpose of procurement by including indicators on project procurement performance and risk rating, the number of issues reported in Implementation Status and Results Reports, and the number of procurement staff working on the project.

- The Procurement Risk Assessment and Management System considers the implementing agency’s procurement capacities, including its policies and whether there is an experienced specialist to manage project procurement; integrity (for example, audits, corruption risks, and complaints); the quality of procurement documents and activities; the complexity of the project’s procurement arrangements and methods; and market readiness (for example, access to suppliers for project activities).