An Evaluation of World Bank and International Finance Corporation Engagement for Gender Equality over the Past 10 Years

Chapter 3 | Lessons Learned on Results

Highlights

The current model of engagement for gender equality lacks a system to capture, classify, and aggregate results, and there is no consensus on how to operationalize the high-level objectives of the fiscal year 2016–23 gender strategy.

Indicators are inadequately used to measure results and are inconsistently used in reporting, emphasizing more outreach than changes in women’s and girls’ empowerment and World Bank Group contributions to reducing gender inequalities. Most projects have a zero baseline for gender-relevant indicators.

Weak attention to implementation and drawbacks in the approaches adopted by the World Bank and the International Finance Corporation hinder the achievement of results. The evaluation identifies promising practices, which, if institutionalized, would make World Bank and International Finance Corporation support to gender equality more impactful and sustainable.

The World Bank and the International Finance Corporation are increasing their efforts to address gender inequalities in institutions, resources, and agency. However, most projects analyzed in the case studies do not sufficiently consider the interconnections and complementarities among these three dimensions, which undermine their effectiveness.

Country case studies show that the Bank Group can “internalize”—that is, anticipate and respond to—the external factors that influence the engagement for gender equality and its results, seizing key opportunities and addressing binding constraints to be more impactful.

This chapter discusses the challenges the World Bank and IFC face to track the results of their engagement for gender equality, explains why more attention is paid to design than implementation, and provides insights on results. The chapter discusses the reasons little evidence of results is found while describing the types and examples of results achieved using primary source data collection. The chapter also analyzes factors that enable and constrain the achievement of results.

The lack of a harmonized system to measure and report results of the Bank Group gender equality engagement at different levels is a challenge for the evaluation. Outcomes are not adequately documented, and no system exists to classify and aggregate them at the corporate level. Thus, this evaluation is unable to provide a quantitative account of results by type (process, outputs, and outcomes); areas of gender inequalities; elements of the theory of change; and other dimensions (sustainability, scale, and ownership). Nevertheless, based on the analysis of dozens of projects in eight countries, this chapter provides insights on how the design and implementation of the theory of change for gender equality in projects—influenced by several enabling and constraining factors—can contribute to reducing gender inequalities.

Limitations of Monitoring and Evaluation Systems

The current model of engagement for gender equality is not able to show results systematically. The Bank Group documents the results of specific interventions1 and conducts impact evaluations of specific project components, but its monitoring systems do not aggregate, classify, and organize results of the World Bank and IFC engagement in a systematic way. Corporate reporting on achievements in gender equality focuses on tracking gender tags and flags and signaling promising designs. Thus, the Bank Group is unable to assess the type of results achieved in supporting countries to move toward gender equality and determine whether this support generates change. For example, the FY16–23 gender strategy updates to the Board of Executive Directors and the World Bank and IFC 10-year retrospectives,2 both published in 2023, inform on the evolution of the engagement for gender equality, types of projects financed, and lessons learned from the engagement, without providing evidence of the results achieved because data on results are not available. This similar type of reporting also occurs in the Mid-Term Reviews of the regional gender action plans. A key informant of this evaluation states, “If we take the fact that every single project in the region had to have something on gender, then, yes, we achieved results. If we ask something more concrete, for example, on saying whether there is improved access to more and better jobs for women, this is more difficult to assess.”

Little evidence of gender results exists because the results are variably interpreted. At the corporate level, it is unclear what the results of gender equality engagement should be and how they should be expressed. Key informants define results differently, varying from a decrease in gender inequalities in the countries to specific outputs achieved by projects, to an increase in the proportion of gender-tagged projects, to improvements in design and processes. For example, 64 percent of IFC key informants in corporate interviews define gender results in relation to projects, 30 percent in terms of corporate achievements, and 18 percent in relation to the country or industry. Strategic documents also do not provide a clear and homogeneous definition of results. Moreover, the in-depth portfolio reviews of the eight case study countries find that projects with a robust theory of change supporting a clear identification of gender outcomes are rare. The absence of a robust theory of change makes it difficult to identify appropriate intermediate results. The varying definitions of the results of the gender engagement (that is, what success should look like) do not help the World Bank and IFC teams come to a common understanding of their goals and how to measure change.

Another reason little evidence of gender results exists is the weak capacity to measure and report results consistently. The Bank Group struggles to report country-level gender results of World Bank and IFC engagement. Performance and Learning Reviews and Completion and Learning Reviews generally report gender results as project-specific outputs, outcomes, and activities, rather than contributions to the reduction of gender inequalities in the country. Only 20 percent of the CPFs reviewed include indicators that allow the reduction of gender inequalities to be measured at the level of the CPF objectives and higher-level objectives.

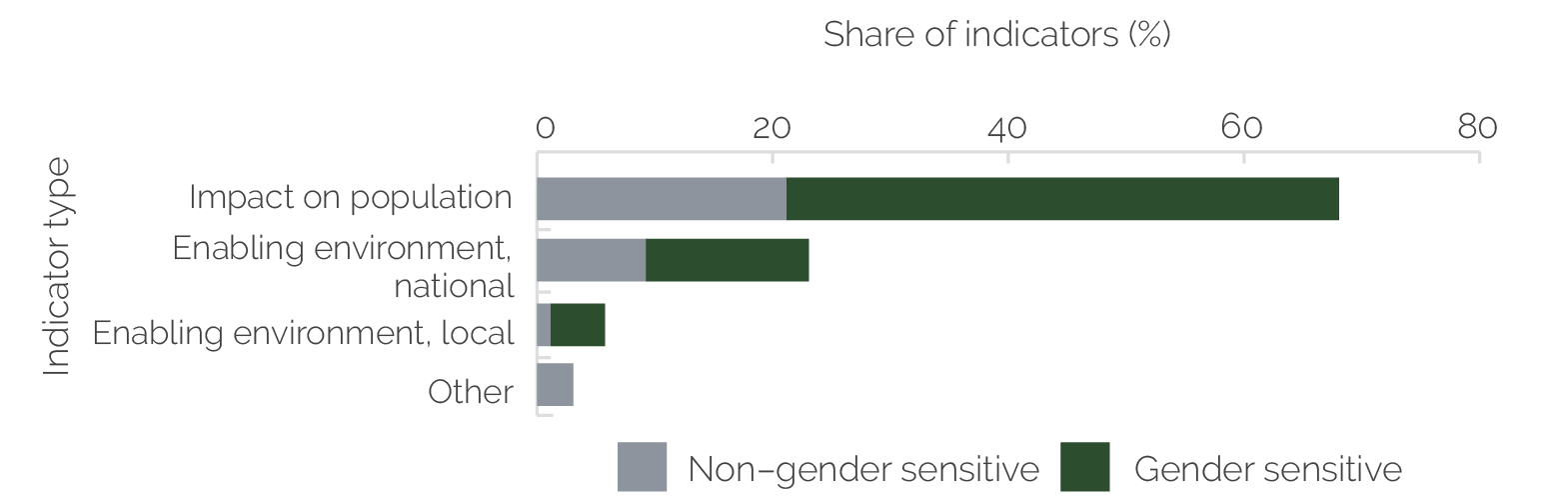

DPO reporting of country-level outcomes also has shortcomings. DPOs report on gender outcomes at the country level in terms of improvements of the enabling environment for gender equality (for example, data, policies, laws, institutional frameworks, budget allocations, and actors’ capacities) at either the national or the local level and the impact of the reforms supported by the DPO on female and male access to services, resources, and other benefits. More than one-third of DPO indicators associated with gender actions are not gender sensitive3 (figure 3.1). Moreover, 81 percent of closed gender-relevant DPOs aimed to achieve and measure outcomes related to the impact of gender-relevant reforms on populations. However, only 52 percent of the indicators measuring these outcomes achieved their target. This raises questions on how these indicators and targets are chosen, how the theory of change of the DPO is developed, and whether the difference between contribution and attribution needs to be clarified.

Figure 3.1. Type of Indicators Associated with Gender Actions in Gender-Relevant Development Policy Operations

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The analysis covers 95 gender-relevant development policy operations identified based on a greater than 15 cutoff value of the gender-relevant score approved between fiscal years 2012 and 2023. These development policy operations had 260 indicators associated with actions that were deemed gender relevant.

Unresolved tension between attribution and contribution makes it difficult to define and measure gender outcomes at the country level. This tension determines which indicators are chosen and then which results are reported and can also influence which activities are selected to achieve gender results (according to key informants). The excessive focus on attribution can foster risk aversion, overuse of output rather than outcome indicators, and an inclination to work in silos as opposed to seeking collaborations. As The World Bank Group Outcome Orientation at the Country Level indicates, the strong focus on attribution does not allow capturing of country-level outcomes that the Bank Group contributes to because of the use of multiple instruments and complementarities with other actors (World Bank 2020b). Thus, a mismatch occurs between the long-term goals the institution wants to pursue and the country result frameworks that rely on lower-level indicators. Capturing the Bank Group contribution to country outcomes requires a shift from attribution to contribution and from project-focused results to countrywide outcomes and changing incentives accordingly. This holds especially true for gender outcomes, which result from cross-sector and cross-institution collaborations, external partnerships, and long-term engagement with country actors.

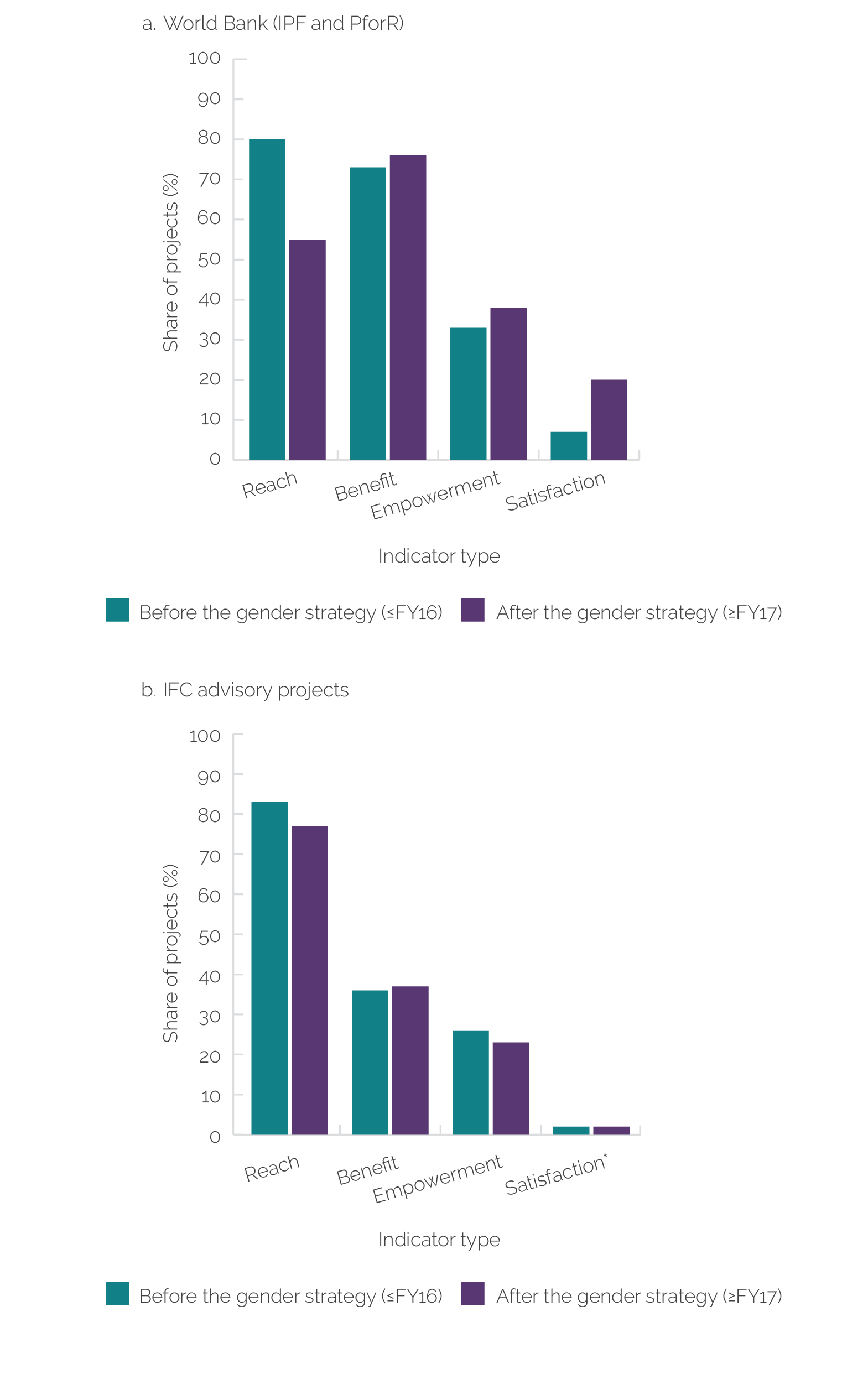

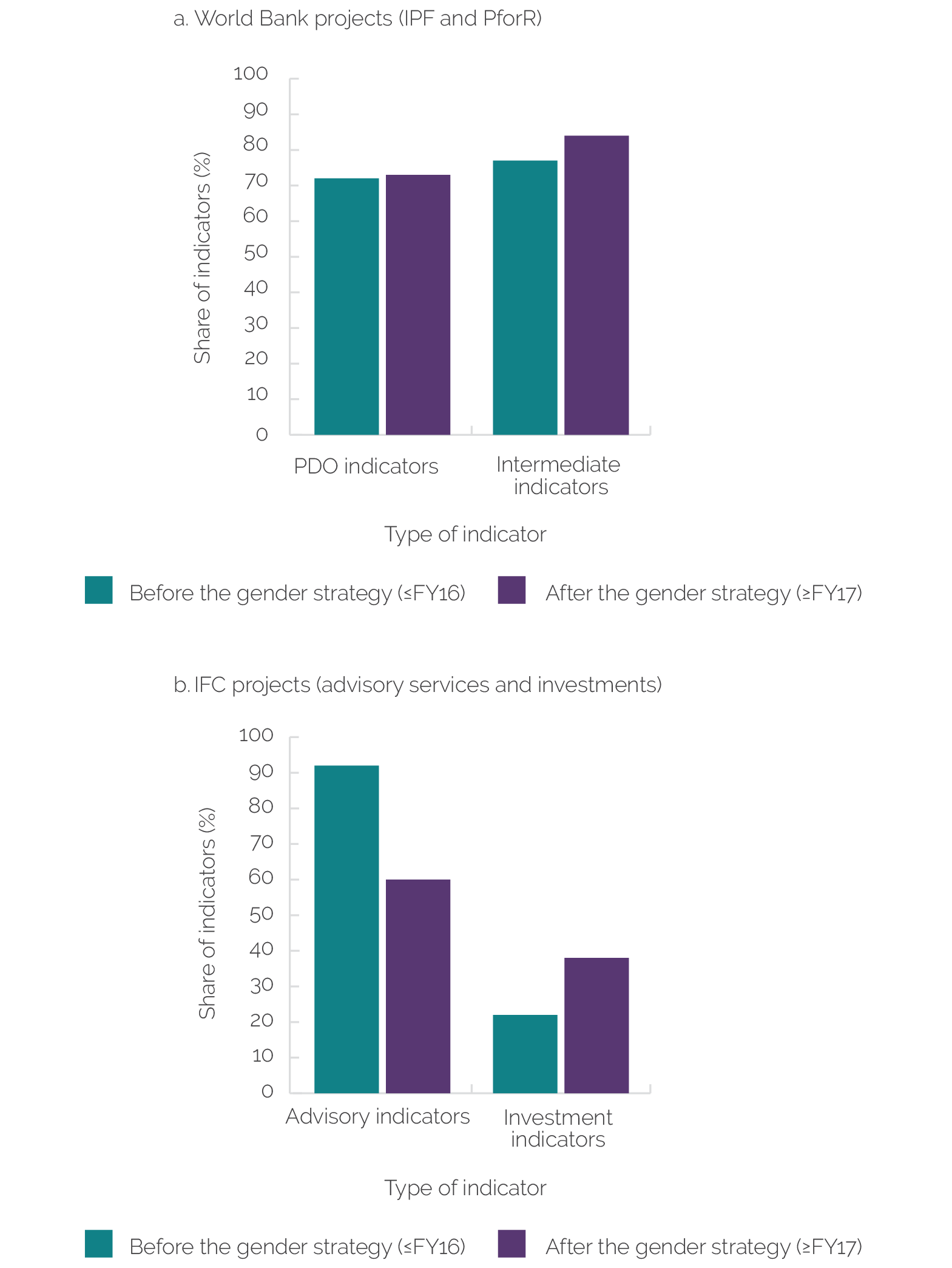

At the project level, completion reports rely on weak indicators that look at outreach numbers more than empowerment. Almost all gender-relevant projects—World Bank lending projects, IFC investments, and IFC advisory projects—include gender-relevant indicators (a precondition for receiving the gender tag and the gender flag), but the nature of these indicators is uneven. Approximately 50 percent of indicators measure only the outreach of the project to women, although for the World Bank, the percentage of projects that used only this type of indicator drastically decreases in the post-strategy period. In the pre-strategy period, 26 percent of World Bank projects used only outreach indicators; this percentage falls to 4 percent in the post-strategy period. For IFC, the share of projects with outreach measures remains the same (approximately 80 percent) for advisory indicators and increases for investment indicators4 (from 40 percent before the strategy to 70 percent afterward).5 For both the World Bank and IFC, indicators measuring women’s and girls’ empowerment are used less frequently than indicators measuring access to or benefits from services provided by the project (figure 3.2). Most empowerment indicators (71 percent) are in projects addressing gender inequalities in labor force participation, including entrepreneurship.

Figure 3.2. Types of Indicators Used in World Bank and International Finance Corporation Gender-Relevant Projects

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: For the World Bank, the analysis covers a sample of 200 randomly selected projects approved between FY12 and FY23, out of which indicator data are available for 195 projects. A total of 435 indicators were analyzed for 89 lending projects deemed gender relevant, identified based on a greater than 15 cutoff value of the gender-relevant score. The review of IFC indicators covers 279 gender-relevant investment projects in selected industries (Financial Institutions Group; Manufacturing, Agribusiness, and Services; and Disruptive Technologies and Funds) and 248 gender-relevant advisory projects in selected business lines (Financial Institutions Group; Manufacturing, Agribusiness, and Services; and Environmental, Social, and Governance). IFC gender-relevant projects were identified based on a greater than 15 cutoff value of the gender-relevant score. The indicator category types are not mutually exclusive—that is, a single project could have all four types of indicators. FY = fiscal year; IFC = International Finance Corporation; IPF = investment project financing; PforR = Program-for-Results. *IFC advisory services projects have client surveys to assess satisfaction, but they are often not part of the monitoring and evaluation framework.

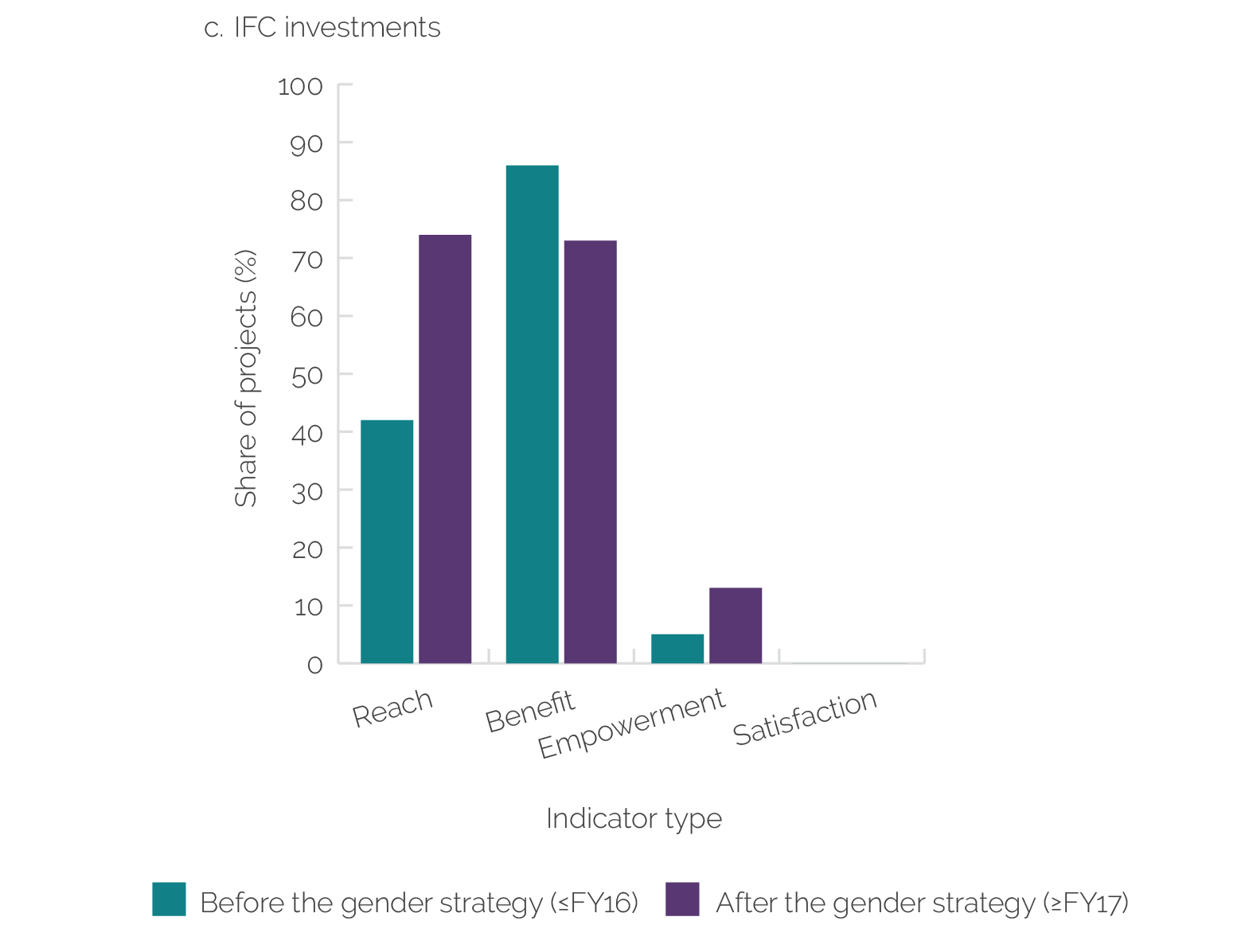

Projects rarely measure the extent to which gender inequalities are reduced because they lack baselines. A decrease in gender inequalities can be determined only by comparing the situation at the start of the project and at project closing, which calls for a baseline. Most gender-relevant indicators of World Bank lending projects have a zero baseline, irrespective of whether they are intermediate or PDO indicators (figure 3.3, panel a). Moreover, the percentage with zero baseline has not changed much in the post–gender strategy period. IFC advisory project indicators with a zero baseline have notably decreased after the strategy; however, approximately 60 percent still lack a baseline (figure 3.3, panel b). The situation is better for IFC investments, despite the percentage of indicators with zero baseline increasing in the post–gender strategy period (figure 3.3, panel b). Zero baselines may be due to lack of data at the start of the project or, more commonly, due to projects accounting only for the outputs they generate as opposed to changes in the context.6 Project Completion Reports7 of gender stand-alone projects measure gender results more systematically, but even they often lack robust indicators, with most at the output level; moreover, over half of their PDO indicators have zero baseline.

Figure 3.3. Indicators with Zero Baselines

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: For the World Bank, the analysis covers a sample of 200 randomly selected projects approved between FY12 and FY23, out of which indicator data are available for 195 projects. A total of 145 PDO indicators and 290 intermediate indicators were analyzed for 89 lending projects deemed gender relevant based on a greater than 15 cutoff value of the gender-relevant score. For IFC, the analysis covers all IFC advisory and IFC investment evaluated projects between FY12 and FY23 (identified based on a greater than 15 cutoff value of the gender-relevant score), out of which indicator data are available for 66 evaluated advisory and 21 (out of 23) evaluated investment projects with relevant gender indicators. The review analyzed 140 outcome (and impact) advisory service indicators and 45 investment indicators. FY = fiscal year; IFC = International Finance Corporation; IPF = investment project financing; PDO = project development objective; PforR = Program-for-Results.

World Bank and IFC projects achieve results that the Bank Group does not systematically track. IEG’s assessment of country engagement for gender equality in eight countries—corroborated by hundreds of interviews and more than 100 focus group discussions—points to a richer, varied, and sometimes contradictory set of results that escape the Bank Group’s current monitoring and reporting systems. These results can be captured only through ad hoc investigation (which greatly limits the ability to learn what works on a systematic basis). For example, in Peru, the Improving the Performance of Non-Criminal Justice Services Project supports Asistencia Legal Gratuita (ALEGRA) centers in providing legal support and information to vulnerable women (including GBV survivors), thus empowering them to understand and assert their rights. Female beneficiaries and ALEGRA centers’ staff consulted by IEG report women’s increased awareness of their rights, sense of psychosocial well-being, and sense of protection and agency. Yet the Implementation Completion and Results Report of the previous project (Justice Services Improvement Project II) does not capture this increased empowerment of women (World Bank 2016a), nor do the indicators of the new project, which measure only people’s access to ALEGRA services (without distinguishing between men and women) and women’s level of satisfaction with services (without capturing the benefits received and changes in women’s lives).8 In Tanzania, IFC’s Finance2Equal platform includes only an indicator on the number of female middle- and higher-level management staff in its results framework. One of the clients supported shows gender results that are not captured by indicators—that is, a reduction in the pay gap between men and women and the establishment of mentoring programs for women (which promotes sustainability).

The limited availability of sex-disaggregated data and gender statistics constrains the measurement of gender results. IFC has supported clients and partners in setting up sex-disaggregated data systems for investments, for example, through the yearly data collection requirement of gender-specific indicators and direct client support provided by advisory services. However, according to IFC’s key informants, establishing gender indicator baselines remains challenging because many clients still do not have sex-disaggregated data. A Retrospective of IFC’s Implementation of the World Bank Group Gender Strategy, 2016–2023 confirms this finding (IFC 2023). The World Bank also lacks sex-disaggregated data. Although many countries increasingly collect sex-disaggregated data and produce gender statistics also thanks to the support of the World Bank, several key informants state that sex-disaggregated data in some sectors are still not available.

Focus on Project Design More Than Implementation

The case studies show that weak implementation of design is one reason why projects are less successful in reducing gender inequalities and fostering women’s and girls’ empowerment than what is expected. Gender Equality in Development: A Ten-Year Retrospective confirms that “significant effort has been made at the design stage; greater focus and systematic effort to support implementation could strengthen results” (World Bank 2023d, 36). IEG’s Mid-Term Review of the FY16–23 gender strategy (World Bank 2021b) previously concluded that monitoring commitments and assessing the quality of project design get significant attention while monitoring implementation gets less attention, which raises the risk of missing evidence to assess outcomes. An example of promising design that reduced its transformative potential in implementation is the Sahel Women’s Empowerment and Demographic Dividend (SWEDD) project assessed in Benin by this evaluation (box 3.1), the effectiveness of which was undermined by various weaknesses in implementation.9

The Bank Group’s gender architecture provides insufficient support to operational teams for project implementation. Several Bank Group staff and implementing partners indicate that they would need support during implementation. This support is constrained by a lack of dedicated gender experts in the countries who can follow the implementation of projects. The gender focal points are frequently overburdened because assisting teams on gender issues is an additional task to many other assigned tasks. Moreover, World Bank and IFC project teams have insufficient knowledge and skills to implement gender-related design. According to the staff survey, 54 percent of respondents (most of them TTLs or team members of gender-relevant projects) never received any training on gender issues; 90 percent received some form of support at the stage of project design (either from the World Bank or IFC staff or from ad hoc consultants); and only 17 percent received support or guidance during project implementation. A key informant states, “People do [not] know how to implement the design; they do [not] necessarily have the expertise. The [World] Bank should ensure that they have this expertise. It would be necessary to provide support during implementation, but it is not possible.”

Corporate incentives are skewed toward directing Bank Group staff to produce a gender-relevant design. The main incentive to integrate gender into projects—the gender tag or the gender flag—is operating only at design. The human resources that are budget coded for gender support face a trade-off: invest their time in gender tagging or support project teams during implementation. This trade-off has become more acute for the World Bank because of the de facto corporate target of 100 percent gender-tagged projects that is enforced by some regions; it usually gets resolved by using the dedicated expert’s time for tagging. A key informant explains, “We need more implementation support to projects. The safeguard specialists are often looking at gender implementation, but they do [not] have the expertise. We need to focus more on implementation. Regions have these 100 percent mandates for design. We are spending a lot of time on design and not on implementation.”

Inadequate skills for implementation negatively affect effectiveness. Case studies and World Bank analytic work show that a good gender design does not guarantee achievement of gender outcomes, particularly if the project does not benefit from ongoing support and sufficient adaptation to overcome potential barriers. For example, a pilot training on psychological and socioemotional skills for female entrepreneurs was replicated in Ethiopia after an impact evaluation indicated that, as a result of this intervention, Togolese female entrepreneurs who followed a traditional business training had increased their profits by 40 percent (Campos et al. 2018). In Ethiopia, however, the training was not as effective; the impact on business performance was mixed because the quality of delivery seemed to matter (Alibhai et al. 2019). Similarly, a McKinsey & Company’s report highlights that gender diversity initiatives often fail when implementation teams lack training in unconscious bias, gender dynamics, and inclusion strategies. This leads to a lack of buy-in from male employees and ineffective interventions (McKinsey & Company 2023). Several of the project teams and implementing partners interviewed also confirm that one of the main constraints to achieving gender results is the lack of capacities—of the World Bank and IFC project teams or partners—for the implementation of activities to advance gender equality.

The presence of dedicated gender experts during implementation and partnership with knowledgeable and experienced local partners are critical for well-designed projects to maintain their gender relevance during implementation and to achieve results. The Australian Gender Pillar in Viet Nam, the Health and Gender Support Project for Cox’s Bazar District in Bangladesh, the Early Years Nutrition and Child Development Project in Benin, the Lima Metropolitano North Extension Project and the Centralized Emergency Response System Project in Peru, and Banking on Women in Egypt are examples of World Bank initiatives analyzed in the country case studies that demonstrate how the strong support of gender or GBV experts during implementation or skilled implementing partners bolster effective implementation of well-designed projects. IEG also observes that some poorly designed projects become more effective in reducing gender inequalities when there is an investment in gender knowledge and expertise and the adoption of effective approaches during implementation. For example, the Saweto Dedicated Grant Mechanism for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in Peru Project incorporated gender-relevant actions to enable women’s participation and leadership only at the implementation stage, which was accompanied and adjusted by the implementing partner who positioned gender high on the agenda, including in local partners’ governance. Also in Peru, the IFC Apurimac Mining Agriculture advisory services project did not initially incorporate gender issues, but it reacted to elements that emerged during implementation that called for a gender assessment and specific activities to be integrated into the project. The project succeeded in achieving gender results, particularly in increasing women’s economic empowerment (IEP 2018).

The 2024–30 gender strategy highlights the need for stronger attention to implementation and intends to develop an implementation plan. The strategy’s stronger focus on implementation was welcomed by several of the World Bank and IFC staff interviewed, who expect to receive greater support. This evaluation provides lessons and recommendations to inform the implementation of the new strategy.

Implementing the Theory of Change of the World Development Report 2012

Most gender-relevant projects overlook existing gender inequalities in institutional structures, distribution of resources, and women’s and girls’ agency and the strong interlinks among them. Advancing gender equality requires that all three elements of the theory of change for gender equality are fulfilled: access to and control of resources, conducive formal and informal institutions, and increased women’s and girls’ agency (figure 1.2; appendix B). World Bank and IFC operations can intervene on just one dimension, but they need to verify that the conditions attached to the other dimensions are in place and, if not, that other Bank Group, government, or other stakeholder interventions do address those gaps. Although there are notable exceptions, most projects analyzed in the case studies do not sufficiently consider the interconnections and complementarities among the three dimensions. An increasing number of knowledge products stress the importance of combining these three dimensions, but their message is weakly transferred into project designs.

IEG has found good examples of gender-transformative designs—most of them recent—resting on comprehensive theories of change that consider the interlinks among the three elements. One example is the SWEDD project described in box 3.1. Another transformative intervention is IFC’s Pacific Women in Business Program in Papua New Guinea and the Waka Mere peer learning platform in the Solomon Islands, which built the business case for addressing GBV in the workplace by estimating the cost of GBV to companies in terms of lost productivity, absenteeism, and turnover. Building on this knowledge, the program targeted both the firms and the industry by partnering with the Business Coalition for Women in Papua New Guinea and the Chamber of Commerce and Industry in the Solomon Islands to support the implementation of gender policies and programs for promoting gender diversity in participating firms (institutions). Training was provided to staff and managers (institutions) by the peer learning platforms on topics such as women’s safety on remote worksites and women’s leadership certification, the latter of which contributed to increasing women’s promotions and income generation (agency and resources). The program also supported the establishment of a case management and safe house service for victims of violence in the workplace (resources).

Box 3.1. The Sahel Women’s Empowerment and Demographic Dividend Project

The Sahel Women’s Empowerment and Demographic Dividend was launched in 2015 in six countries and subsequently expanded to other countries, including Benin (a case study country for this evaluation). The project aims to increase women’s and adolescent girls’ empowerment and their access to quality reproductive, child, and maternal health services in select areas of the participating countries and to improve regional knowledge generation and sharing and regional capacity and coordination. The Sahel Women’s Empowerment and Demographic Dividend project ultimately intends to help Sahel countries capture the demographic dividend by decreasing their fertility rate and better leveraging women’s and girls’ potential for development.

The project has a comprehensive theory of change that aims to (i) enhance women’s and girls’ agency through their participation in safe spaces for life skills development (resources) and increase schooling (resources) and economic empowerment (resources); (ii) shift gender norms (informal institutions) through multichannel communication and engagement with men and boys and with opinion leaders, including customary and religious leaders; and (iii) change formal institutions, including strengthening data production and use, policies, laws, and the quality and coverage of the sexual and reproductive health services system.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

When providing support to women’s economic empowerment, the World Bank and IFC focus more on access to resources than control of resources. Women’s access to credit, cash transfers, or skills does not automatically translate into women controlling and benefiting from them. Yet the World Bank and IFC promote women’s and girls’ access to resources while often neglecting to monitor and support women’s and girls’ use and control of these resources—that is, women’s and girls’ agency and the influence of informal institutions, such as gender norms and gender power relations. IEG finds, for example, that some loans provided by the Sustainable Forests and Livelihoods Project in Bangladesh, which supported women’s access to finance for income-generating activities, were used by male household members for their own activities. IFC projects that focus on increasing either women’s access to finance or income (employment) often do not capture changes in women’s decision-making power or use, control, and ownership of resources. An exception is an IFC project in Bangladesh, which supported the provision of mobile financial services to underprivileged women. A postcompletion assessment shows that the women beneficiaries increased control over their income and household resources and their participation in household decisions.

When the Bank Group aims to facilitate women’s control over resources by promoting asset ownership, gender norms and power relations can constrain the achievement of this goal. The Bank Group’s analytic work recognizes that law reforms aimed at reducing gender inequalities in asset ownership can be difficult to implement. For example, the South Asia GIL finds that legal reforms are not enough to eliminate gender inequality in inheritance and land distribution. The evidence on inheritance is mixed, with some studies suggesting a more gender-egalitarian inheritance pattern after the reform and others finding no impact (Zahra, Javed, and Munoz Boudet 2022). In Tanzania, the World Bank Land Tenure Improvement Project promoted joint land titling by establishing partnerships with local CSOs, which organized information and awareness-raising activities in the communities. Some key informants reported that these activities were not always effective because, in some communities, women feared that joint titling could compromise family harmony or threaten the husband’s breadwinner role. A lesson learned from a pilot initiative conducted by the Africa GIL in Uganda is that strong incentives (conditional offer of titling in this case) can notably increase the acceptance of joint titling (Cherchi et al. 2018). Nevertheless, women’s ownership of assets does not automatically imply control. An IFC market study on women-owned small and medium enterprises in Indonesia highlights that women would need their husband’s permission to use their own assets (especially housing) as collateral or capital (IFC 2016). The World Bank Inclusive Housing Finance Program in Egypt shows that gender norms and power relations can undermine the power of incentives to ensure women’s control of assets. The program intended to increase women’s access to mortgages by giving priority to female heads of households and providing incentives to joint titling in formal registration processes. The evaluation finds that the project did increase women’s homeownership, especially among female heads of household, and the social acceptance of female property. However, key informants reported that some women signed a private agreement with male household members to surrender the property.

The majority of World Bank and IFC projects target women and girls as individuals, overlooking the relations and norms in which they are “embedded” that strongly influence their choices and empowerment opportunities.10 Despite abundant World Bank and IFC analytic work demonstrating the implications of gender norms and gender power dynamics for advancing gender equality,11 projects often do not consider these implications. For example, projects promoting women’s economic empowerment rarely monitor or promote women’s decision-making and bargaining power within the household. Two examples are environmental projects supporting women’s income-generating activities and community leadership in Benin and Peru. Based on IEG’s field assessment, these two projects increased women’s income and agency in farmers’ cooperatives and community life but did not change their position in the household. In Tanzania, IFC’s Finance2Equal advisory services project led to a significant increase in women’s middle management positions in financial institutions but not in higher-level management positions. Gender norms and power relations may have prevented qualified women from accepting these positions, which could have required relocations to other branches—a decision generally made by men.

The World Bank and IFC also overlook the influence of gender power relations and norms within communities and social networks. Many Bank Group projects promote women’s community leadership by establishing mandatory quotas of women in community management committees or project activities without considering whether gender norms in the target communities allow women to participate in decisions, speak in front of men, or participate in activities with men who are not their family members. For example, in Egypt, IFC training for women aspiring to be on corporate boards was comprehensive and appreciated, but it did not lead to women’s nominations to boards because even when women qualified for the positions, they were often excluded from business networks. In Bangladesh, the Sustainable Forests and Livelihoods Project fostered women’s participation in forest management by mandating a quota of 33 percent of women involved in villages’ forest management committees. One committee activity involves pairs of individuals patrolling the forest to monitor and report unauthorized tree cutting. Achievement of the female quota in committees did not correspond to women’s effective participation because women refused to patrol the forest with men who were not their family members.

The World Bank and IFC are increasing their engagement with men and boys to advance gender equality, although structured and effective approaches are rare. The World Bank has produced knowledge on this topic (such as Pierotti, Delavallade, and Brar 2023), but few projects include structured interventions to engage men and boys for gender equality. The IEG review of gender stand-alone projects finds that 17 percent of World Bank projects engage men or boys in some way, but only 8 percent promote in-depth engagement that goes beyond sensitization, for example, by targeting men or boys to promote positive masculinity12 and shared decision-making. Almost all these projects were designed after the FY16–23 gender strategy.13 For IFC, only 5 percent of stand-alone projects engage with men and boys in some form. Some emerging IFC programs—such as those on women’s leadership, GBV, and childcare—engage men and boys as champions and business leaders for gender equality in capacity-building efforts. Evidence on IFC’s Women in Work program in Sri Lanka indicates that the involvement of male business owners in workshops and training events on recruiting, promoting, and retaining women and in the implementation of effective anti–sexual harassment mechanisms increased the recognition and formalization of women’s role in the business. At the same time, gender stereotypes (such as women’s tidiness and ability to multitask) were not addressed and were used to justify women’s new roles, and the conflict between paid and unpaid work—which was amplified by women’s increased participation in value chains—was also not addressed (DFAT 2022).

Engaging men and boys can be effective only as part of holistic and long-term interventions. Some projects that IEG analyzed in the case studies engaged with men and boys for gender equality using structured approaches but struggled to be effective. In Benin, the SWEDD project engaged with men and boys to support the empowerment of women and girls, their access to sexual and reproductive health, and their protection from GBV. However, its effectiveness was diminished because of the component’s limited scale and short duration and weak motivation for the men and boys to take part in the activities without deriving any tangible benefit. An Africa-led GIL impact evaluation of the Engaging Men through Accountable Practice approach to engage men in group discussions to reduce intimate partner violence finds that the attitudes of the participants changed, but intimate partner violence did not decrease (Vaillant et al. 2020). This suggests, in line with other existing literature, that this type of intervention needs to be longer in duration and more holistic.14 These findings are relevant for the 2024–30 gender strategy that intends to strengthen the engagement of men and boys for gender equality.

Supporting women’s and girls’ empowerment without considering gender power relations increases the risk of GBV. This risk is well documented in the literature (Bulte and Lensink 2019; Désilets et al. 2019; Edström et al. 2015; Eggers del Campo and Steinert 2022; Kiplesund and Morton 2014; World Bank 2023a), and it materialized, for example, in the Peru Decentralized Rural Transport Project. The project brought positive results in women’s agency and access to economic opportunities, but many female workers in road construction projects reported facing severe mistreatment from their spouses, including domestic abuse. Their husbands expressed discontent over the women’s prolonged absence from home and, in some cases, felt jealous of their wives’ higher income (Casabonne, Jiménez, and Müller 2015).

The World Bank and IFC have progressively increased their engagement on GBV by both mitigating GBV in projects through safeguard policies and addressing GBV to advance gender equality and empowerment in countries and industries. The number of projects that address GBV progressively increased over the evaluation period across all Bank Group instruments. The alarming surge in GBV during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–22) further increased the urgency to address GBV. The World Bank’s 10-year retrospective on GBV prevention and response in World Bank operations reported a more than tenfold growth in lending operations (both IPFs and DPOs) focusing on GBV during 2012–22 (World Bank 2023c).15 The increase of GBV interventions in the Bank Group portfolio coincided with an increase in strategic recruitment of GBV specialists at headquarters and in country offices16 to provide technical expertise and support at different levels. In Papua New Guinea, IFC has helped clients develop guidance, build coalitions, provide training, and establish safe houses and showed early results in increased productivity and cost savings. This engagement was foundational for IFC’s work on gender, and the model has been replicated elsewhere in the region (IFC 2023). Since COVID-19, IFC staff have also received increased requests from operational teams to help mitigate and address GBV in projects to advance gender equality. According to key informants, however, this surge in requests has not been met with a corresponding increase in GBV experts across the institution. Many key informants also stress the need to clarify roles and responsibilities in relation to risk mitigation (safeguards role) and to addressing GBV to advance gender equality (advisory support to GBV).

Health and transport interventions provide crucial opportunities to effectively address GBV and strengthen prevention and response systems. Effective GBV response interventions address both supply and demand—they strengthen institutions’ response to GBV while addressing barriers to survivors’ reporting and expanding access to services offering healing and recovery. In Bangladesh, the Health and Gender Support Project for Cox’s Bazar District achieved positive results in GBV survivors’ health service use through a comprehensive approach that strengthened the institutional capacity to deliver quality health services and enhanced communication and community engagement with the refugee population. Yet the project’s field visits highlighted shortcomings in implementing the engagement with men and boys component and issues with ensuring the sustainability of results. In Peru, the Lima Metropolitano North Extension Project led to an improved sexual assault reporting and referral system in the capital’s transport network through the development and adoption of a new sexual harassment protocol, coupled with the national counterpart’s expertise and commitment. In both projects, a robust theory of change, combined with the implementing partner’s strong expertise in GBV, World Bank sectoral gender expertise, and collaboration with other skilled actors, proved key for the high design quality and effectiveness.

Some interventions that seek meaningful community engagement and activism are promising efforts to help prevent GBV, although their effectiveness still needs to be proven. The existing evidence shows that GBV can be prevented through solid interventions based on in-depth, multiyear intensive community mobilization to shift harmful gender attitudes, roles, and social norms and highlights that these interventions are highly complex and require considerable intensity, time, skills, and contextual adaptations (Kerr-Wilson et al. 2020; Le Roux and Palm 2021). For example, the SWEDD project foresees the empowerment of women and girls and engagement with men and boys, faith and customary leaders, and overall communities to create conducive environments for gender equality and catalyze shifts in the entrenched social norms underpinning GBV (including child marriage). A field assessment in Benin, however, shows that implementation efforts still need to be intensified and deepened in line with global evidence to be most effective.

World Bank and IFC projects rarely support women’s and girls’ collective agency for the advancement of gender equality. The WDR 2012, FY16–23 gender strategy, and Bank Group’s analytic work (Klugman et al. 2014; Zahra, Javed, and Munoz Boudet 2022) highlighted the potential of women’s collective agency to achieve gender outcomes, but only a few Bank Group initiatives do so. For example, only 7 percent of World Bank and 15 percent of IFC advisory stand-alone projects support women’s collective agency. Bangladesh, of all the case studies, stands out for its support to self-help groups to enhance women’s economic empowerment; across regions, a form of support to women’s collective agency is the promotion of women’s cooperatives in agriculture value chains and forestry projects. In Benin, for example, the West Africa Coastal Areas Resilience Investment Project supported women producers to register their informal groups as cooperatives and also provided training on cooperative management to board members. Women participating in IEG’s focus groups consider the registration a benefit because it provides the opportunity to establish partnerships and receive funds (although they have not encountered any opportunity yet). Some of the participants also note that they have “learned how to stay together and organize [themselves].” In India, IFC’s partnership with the Self-Employed Women’s Association helped an associated housing entity facilitate access to housing for informal low-income female borrowers and expand geographic reach outside Gujarat. The program supported poor women’s access to housing through the provision of land rights based on informal land tenure by creating assets in their names and making them shareholders of the start-up. Similarly, in Papua New Guinea, IFC supported the creation of a business coalition for women that led to behavior changes in 45 firms through the implementation of 93 policies and practices. The coalition now operates as an independent business entity.

Institutional change through legal and policy reforms is less effective if the challenges to reform implementation are not adequately accounted for. The Bank Group’s analytic work shows that legal and policy reforms for gender equality are ineffective when weak institutional capacities and adverse gender norms constrain their implementation (Klugman et al. 2014; World Bank 2023a). In Egypt, the DPO gender pillar supported labor law reforms to remove constraints on women’s employment in some jobs. However, as a key informant reported, “allowing women to work at night does not mean that women will do it [work at night].” The communication campaign to promote the application of the reform was not implemented. Other challenges included weak government buy-in of the implementation phase, weak coordination of the government institutions involved, slow operational procedures, and lack of domestic resource mobilization. In Mauritania, IFC supported the strengthening of the legal and regulatory framework for property rights to foster women and youth entrepreneurship development. Although passing the first property law was considered an essential building block, there is no evidence of implementation of the law, especially with a gender perspective. For almost half the closed gender-relevant DPOs, their duration and attention to the implementation of reforms appears to not match their ambitions, expressed in outcome indicators.

Addressing Constraints, Opportunities, and Aspirations

Addressing constraints on women’s and girls’ participation and empowerment—beyond just targeting female beneficiaries—has increased the effectiveness of projects in advancing gender equality. World Bank analytic work stresses the benefit of analyzing and addressing the constraints on women’s and girls’ participation and empowerment to achieve meaningful results on gender equality. The Africa GIL focuses on the analysis of underlying constraints faced by women in providing analytic support to regional, country, and project teams to develop strategic documents and project designs. Support to female entrepreneurship and employment can be effective when it tailors interventions toward women’s specific needs and constraints rather than just target a quota of female beneficiaries. For example, in Peru, IFC supported a microcredit institution to increase the financial inclusion of migrant women entrepreneurs. The project redesigned the lending product to fit the target group’s needs, address the root causes of migrant women’s exclusion from financial services, and create opportunities to access credit. The intervention also aimed to raise clients’ awareness of their unconscious biases to gender financial inclusion. IEG found projects that did not achieve their expected results on women’s economic empowerment because they did not address the binding constraints that women faced. In Uzbekistan, the World Bank Rural Enterprise Development Project established a minimum share of 33 percent of female beneficiaries from credit lines. IEG found that few of the women received the credit because of several constraints, including their limited power of choice and lack of collateral.

Seizing opportunities to advance gender equality through partnerships increases the ownership, relevance, and effectiveness of interventions. Recognizing complementarities and others’ comparative advantages led the World Bank and IFC to establish collaborations with partners embedded in the countries that contributed specific skills and expertise that boosted the effectiveness of interventions. In Bangladesh, the partnership with the United Nations Population Fund (a United Nations’ agency with expertise in GBV interventions) contributed to an effective response to GBV in Rohingya refugee camps. The Saweto Dedicated Grant Mechanism for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in Peru Project’s collaboration with an experienced international NGO that has established partnerships with Indigenous associations contributed to supporting the leadership and economic empowerment of Indigenous women. The Better Work partnership between IFC and the International Labour Organization led to the Gender Equality Program in the garment sectors of Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Viet Nam that successfully supported female garment workers to advance their careers through technical and soft skills training and communication activities to increase the acceptance of female leadership. In Myanmar, IFC worked with partners such as the Business Coalition for Gender Equality and the Myanmar Hydropower Developers’ Association on successful initiatives such as Respectful Workplaces and Powered by Women.

Several World Bank key informants call for increased involvement with skilled and strongly embedded NGOs to promote collective action and achieve gender results. One key informant adds that NGOs should be involved not only in implementation (as the World Bank normally does) but also in programmatic and policy work to use their context-specific experience to support sustainable change in gender norms. The 2024–30 gender strategy confirms that consultations “called for widening collaborations, especially with civil society,” and commits to promote “wider global, regional, and local stakeholder engagement and partnerships to drive change” (World Bank Group 2024, 9). The new strategy recognizes collective action—defined as “concerted efforts of public and private sector actors, community groups, civil society, global advocacy groups, and international agencies, among others, toward better gender equality outcomes” (World Bank Group 2024, 13)—as one of the three drivers of change toward gender equality.

Some examples of interventions demonstrate that supporting “positive deviants” or “gender champions” to become role models, or role models to become gender champions, can be effective. Some World Bank–financed projects effectively encouraged adolescent girls and young women to enroll in traditionally male-dominated training courses by involving role models for inspiration (World Bank 2023a). In the private sector, women entrepreneurs can increase awareness of gender issues within their businesses and challenge gender norms by serving as role models for younger generations (Quak, Barenboim, and Guimarães 2022). IFC has supported client gender champions as role models and created platforms of exchange to influence other clients, although there is no evidence of results yet. For example, Mexico’s and Viet Nam’s peer learning platforms include some corporate clients as gender champions for childcare and prevention of GBV, who were invited to share their experiences, raise awareness, and foster change. IFC, however, rarely seized opportunities that may have existed outside of the private sector—for example, engaging with not-for-profit local actors, including women’s organizations. Collaboration with business councils in Papua New Guinea is a rare case of engagement with opinion leaders to make them gender champions. SWEDD’s extensive engagement with customary and religious leaders to prevent GBV and promote women’s and girls’ empowerment and sexual and reproductive health is a promising approach because of these leaders’ influence in the community, although, in Benin, it has not yet made an impact.17

Addressing women’s and girls’ aspirations positively affects their empowerment and involves three complementary actions: allowing women and girls to express their aspirations, expanding their aspirations, and supporting them to fulfill their aspirations. Community-driven development projects adopt participatory approaches to identify women’s priorities and monitor the extent to which the project addresses them.18 These projects can be gender transformative by expanding women’s aspirations, for example, by encouraging them to be leaders, form cooperatives, or innovate their activities to increase their income. For example, the Saweto Dedicated Grant Mechanism for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in Peru Project successfully supported bottom-up processes to increase Indigenous women’s economic empowerment and leadership in Indigenous organizations. Similarly, the Forest Investment Program—Decentralized Forest and Woodland Management Project in Burkina Faso demonstrated the effectiveness of bottom-up approaches in supporting women’s economic empowerment and enhancing women’s voice and collective agency (World Bank 2023a).

Yet projects often do not seek, expand, or fulfill women’s and girls’ aspirations, with potentially adverse effects. Many projects plan activities for women and girls without previously consulting them. In some cases, this negatively affects project effectiveness because expanding girls’ and women’s aspirations without the ability to fulfill them generates frustration. For example, the SWEDD project in Benin and Burkina Faso19 struggled to fulfill the aspirations raised in the adolescent girls who were consulted.20 In Benin, the SWEDD project supported vocational training in innovative male-dominated activities (solar panel installation and mobile phone repair) to help out-of-school girls start income-generating activities. Although interested in these activities, the adolescent girls eventually opted for chicken farming—an activity already done by their mothers—because they feared that the new activities had no market in their town and clients would not trust them because they were girls. The project did not influence their family and potential clients or increase the girls’ risk propensity and self-confidence. In Burkina Faso, the SWEDD project supported adolescent girls who were already working as apprentices in male-dominated fields. Girls received training and start-up kits for their microenterprises. The project built on existing adolescent girls’ aspirations and experience, but it did not address the existing constraints to fulfilling them—above all, lack of financial access. Thus, the girls remained apprentices and did not start their own activity. Similarly, field visits to an IFC advisory peer learning platform in Tanzania revealed that girls were still working as apprentices with their former employers. Not a single girl had started her independent activity because of the lack of start-up capital and no financial institution being ready to offer them loans.

The case studies show that the Bank Group can “internalize” external factors influencing engagement for gender equality and its results, seizing key opportunities and addressing binding constraints to be more impactful. Key external factors affecting engagement for gender equality and results that emerged from the country case studies were the governments’ and private sector clients’ commitment, approach, and capacity; governments’ domestic resource mobilization; engagement of development partners and civil society; insurgence and response to crises; and gender norms. Although these factors are not surprising, the analysis of the case studies finds that the Bank Group’s ability to anticipate and respond to them—that is, internalize them by integrating them within the theory of change—enhances its engagement for gender equality. For example, in Benin, the World Bank proactively seized the opportunity of the president’s political engagement on gender equality to enter into high-level policy dialogue with the government on the interlinks among economic development, demographic pressures, and women’s and girls’ empowerment and was able to negotiate two stand-alone lending projects (SWEDD and a DPO). Tanzania’s first female president, Samia Suluhu Hassan, opened new spaces for the Bank Group’s gender engagement and substantial progress in advancing gender equality, which resulted in a stand-alone operation approved in March 2024. Conversely, the political shift toward a more conservative Peruvian government made the policy dialogue on gender equality harder, but the World Bank succeeded in keeping the engagement for gender equality as a result of several ASAs and sector programs in the justice and transport sectors.

Multiple crises have significantly hindered progress, underscoring the need for a more systematic integration of FCV issues in gender equality efforts, even in non–fragile and conflict-affected countries. In some instances, crises have shifted priorities, leading to a downgrading of gender equality, whereas in others, they have generated specific threats to gender equality for population subgroups affected by FCV. The COVID-19 pandemic, for example, aggravated gender inequalities and the vulnerability of women and girls, hindered the implementation of activities, significantly altered all countries’ priorities, and temporarily reduced the investment of financial resources for gender equality. Governments negotiated with the World Bank to reallocate funding in project budgets from gender components to emergency funds to address the pandemic, such as in the Digital Rural Transformation Project in Benin. In several of the evaluation country cases (all non–fragile and conflict affected), pockets of FCV called for specific World Bank approaches to address gender inequalities. For example, the massive migration of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh affected the implementation and effectiveness of most World Bank projects in the region, not just gender equality interventions. In response, the World Bank tackled specific gender inequalities in interventions, such as the Health and Gender Support Project for Cox’s Bazar District, which addressed GBV and reproductive health needs in refugees and host communities.

Achieving Owned, Sustainable, and Large-Scale Gender Outcomes

The World Bank and IFC pay insufficient attention to the sustainability of gender results—a necessary condition for long-lasting progress in gender equality. Few projects show evidence of being sustainable. First, several projects are too short in duration to achieve long-lasting gender equality results because social change needs time. The duration of IFC advisory projects is generally two years, which several key informants consider too short. The duration of World Bank projects is longer but still insufficient, confirmed by several key informants at the national and local levels. Second, many projects do not include a clear strategy for sustainability. For example, subprojects in the SWEDD project in Benin last two years—a short time to ensure the successful start-up of income-generating activities or girls’ completion of secondary school. Moreover, the kits and cash transfers supporting the schooling of vulnerable girls lack financial and institutional sustainability because they are entirely funded by the project and managed by NGOs. The safe spaces for girls’ skill development also have no sustainability strategy.

The sustainability of new income-generating activities is more challenging and needs a longer time horizon, higher investments, and more knowledge than required by existing activities. In Benin, the West Africa Coastal Areas Resilience Investment Project financed income-generating activities to build resilience to climate change. The project hired experts and subcontracted local NGOs to support local cooperatives to prepare their financing requests and develop business plans. Two mixed male-female horticulture cooperatives that received funds to expand their activity increased their revenue and were clearly sustainable. By contrast, the sustainability of the new activities supported by the project was in doubt. One cooperative of women was waiting for equipment, technical support, and training to produce coconut oil. However, the price of the raw coconut was high, which threatened sustainability. Another cooperative producing biofertilizers had no market to sell them.

Large-scale gender results are achieved through programs supporting sector systems’ strengthening at the national level, but their sustainability is challenging. Sectoral programs of a long duration contribute to large-scale results in gender equality, but they struggle to produce sustainable results because of the lack of domestic resource mobilization and weak capacities of partners. A good practice is the Improving the Performance of Non-Criminal Justice Services Project in Peru, which aimed to support the implementation of Peru’s justice reform by improving the delivery of adequate noncriminal justice services. One project component aimed to strengthen the ALEGRA centers in providing information and legal support to vulnerable women (including GBV survivors) through expansion of coverage, increase in quality, and building of staff’s capacity to manage cases. The large scale and sustainability of gender results were possible because of their integration in the support to countrywide sector reform, investment in institution strengthening of existing services owned by the government, and continuity of engagement (the World Bank has supported the ALEGRA centers since 2011).

Gender-transformative projects based on comprehensive theories of change struggle to go to scale21 and often do not have a strategy to do so. For example, half of stand-alone projects22 are pilot interventions that can be replicated and scaled up. However, among them, only 22 percent indicate in their design a strategy for scaling up. This missing strategy is confirmed by the case studies and IEG’s evaluation of gender inequalities in FCV (World Bank 2023a).

Sustainable gender outcomes owned by communities and local stakeholders are produced thanks to the adoption of bottom-up and culturally sensitive approaches that support endogenous processes of change. Using culturally sensitive approaches that respect and build on traditional values and norms to sustain gender equality rather than aiming to “change wrong traditions” helps projects achieve sustainable results. The Saweto Dedicated Grant Mechanism for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in Peru Project succeeded in increasing women’s economic empowerment and leadership within the communities and Indigenous associations in a sustainable way because of a culturally sensitive and bottom-up approach and strong partnerships between the implementing partners and Indigenous associations. The Early Years Nutrition and Child Development Project in Benin adopted a culturally sensitive and community-based approach to promote men’s engagement in childcare and nutrition. Previously trained local field-workers organized group discussions with men and women in the targeted communities, involving community leaders, to discuss gender roles from their own experience.

- Gender Innovation Labs play a key role in producing knowledge on “what works” to reduce gender inequalities in different sectors.

- In preparation for the new 2024–30 gender strategy, the World Bank Group produced three retrospectives: Gender Equality in Development: A Ten-Year Retrospective (World Bank 2023d), Gender-Based Violence Prevention and Response in World Bank Operations: Taking Stock after a Decade of Engagement, 2011–2022 (World Bank 2023c), and A Retrospective of IFC’s Implementation of the World Bank Group Gender Strategy, 2016–2023 (IFC 2023).

- Gender-sensitive indicators capture gender differences and inequalities—for example, sex-disaggregated indicators and indicators focused on access, benefits, or other outcomes for women or girls (such as the rate of pregnant women’s access to at least four antenatal consultations). Gender-sensitive indicators that focus on the enabling environment capture changes in the system—for example, in policies, laws, data system, institutional framework, and budget allocations—to better satisfy women’s and girls’ specific needs and to advance gender equality (such as the percentage of the public budget allocated for gender-based violence prevention and response).

- This analysis includes Anticipated Impact Measurement and Monitoring indicators. Anticipated Impact Measurement and Monitoring is part of the International Finance Corporation’s approach to evaluating the expected development outcomes and potential positive effects of projects across multiple dimensions.

- For International Finance Corporation advisory, the percentage of projects using only outreach indicators decreased slightly, from 38 percent in the pre-strategy period to 36 percent in the post-strategy period. In contrast, the percentage of International Finance Corporation investment projects with only outreach indicators increased significantly, from 3 percent to 19 percent. This increase was primarily driven by a shift in the portfolio composition—from an overwhelming prevalence of financial market operations during the pre-strategy period, which predominantly use indicators measuring access to credit (a benefit indicator), to the inclusion of other industries that tend to favor outreach indicators during the post-strategy period.

- For example, an indicator can measure how many antenatal care consultations the project has delivered in one year instead of measuring the percentage increase of antenatal care consultations in the targeted maternal health services in one year attributable to the project.

- Completion reports refer to World Bank Implementation Completion and Results Reports, advisory Project Completion Reports, and Expanded Project Supervision Reports.

- The project results framework does not include any indicator capturing the increase in women’s access to Asistencia Legal Gratuita centers. The only existing indicator on access measures the number of requests received by the centers, and it is not sex disaggregated, probably relying on the assumption that most access is by women. The project development objective gender indicator is the “percentage of female users satisfied with the services provided at the [Asistencia Legal Gratuita centers]” (World Bank 2020a, 2). The emphasis on women’s satisfaction is not indicative of actual increased access or improved outcomes.

- Some weaknesses detected in the Sahel Women’s Empowerment and Demographic Dividend (SWEDD) project’s implementation in Benin are excessively short duration of subprojects aimed at women’s and girls’ empowerment and men’s, boys’, and communities’ engagement, undermining the achievement of results; insufficient coordination of the different components and actors; top-down and centralized choice of trade areas for the support of income-generating activities, which negatively affects their relevance and effectiveness; insufficient support to women’s and girls’ economic empowerment and men’s and boys’ engagement; and weak engagement with decentralized authorities and local branches of involved ministries.

- The Independent Evaluation Group found these examples through portfolio reviews of the eight country case studies, the World Bank gender stand-alone projects review, and the International Finance Corporation portfolio review of all evaluated gender-relevant projects (66 advisory and 23 investment projects).

- Several World Bank reports explicitly focus on the impact of gender norms on gender inequalities. Two recent examples are reports by Goldstein et al. (2024) and Muñoz Boudet et al. (2023). The International Finance Corporation knowledge products also acknowledge the importance of gender norms (for example, IFC 2019a, 2019b, 2019c, 2019d, 2020).

- Positive masculinity is the opposite of hegemonic masculinity, frequently defined as toxic masculinity. Positive masculinity promotes more inclusive, empathetic, caring, and egalitarian forms of manhood (Lomas 2013). Positive masculinity “reflects a developmental process towards healthy masculine identities that are supportive of gender equality” (Wilson et al. 2022, 2) and implies the adoption of a perspective that aims to accentuate the strengths and beneficial aspects of a masculine identity.

- Two important exceptions, both approved in 2014, are the Great Lakes Emergency Sexual and Gender Based Violence and Women’s Health Project in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Independent Evaluation Group World Bank Group 89 which included the pilot on Engaging Men through Accountable Practice approach, and the SWEDD project.

- For example, Advancing Learning and Innovation on Gender Norms highlights that the main lesson learned from literature analyzing programs that work with men and boys to achieve gender equality is the need to move away from gender sensitization to an approach based on gender transformation (Kedia and Verma 2019). Changes in men’s knowledge and attitudes must translate into tangible changes in behaviors (which requires working in depth on masculinity with men and boys and at the same time on women’s and girls’ empowerment and working with communities by using male role models and engaging with community opinion leaders).

- The retrospective also indicates how this growth reflects an increased commitment from client governments to allocate resources toward both preventing gender-based violence and enhancing response mechanisms (World Bank 2023c).

- The first gender-based violence expert was recruited in 2017 to join the Gender Group, and five gender-based violence specialists were added to the Social Sustainability and Inclusion team in fiscal years 2017 and 2018.

- According to different key informants, in Benin, the engagement with religious organizations and leaders needs to be strengthened to be more impactful. The religious organizations’ platform at the national level is weakly involved in SWEDD.

- A weakness of these projects is that they did not consider intersectionality—women, youth, ethnic minorities, and other marginalized groups were consulted separately but considered as homogeneous groups. Gender power relations across these groups and among women were not considered, which hid the voices of groups affected by multiple discriminations (for example, poor adolescent girls belonging to a minority ethnic group).

- This evaluation analyzed SWEDD in Benin. Addressing Gender Inequalities in Countries Affected by Fragility, Conflict, and Violence: An Evaluation of the World Bank Group’s Support analyzed SWEDD in Burkina Faso and Chad (World Bank 2023a).

- This finding is based on a deep dive of SWEDD in Benin, including field visits with interviews and focus groups with beneficiaries, local implementing partners, and local and community relevant stakeholders (World Bank 2023a).

- This evaluation makes a clear distinction between replication and scaling up of successful initiatives or approaches to reducing gender inequalities (or “gender-smart solutions” as the fiscal year 2016–23 strategy defines these initiatives or approaches). “Replication” means the repetition, in other countries, of a successful approach to reducing gender inequalities. Successful replication implies new analytic work and the adoption of a learning-by-doing approach (which can take the form of formative research) to adapt the solution to the new specific context and target group and ensure (and monitor) the necessary conditions for a successful implementation. The adaptation should take place during design but also during implementation. “Scaling up” means a significant increase in coverage of a pilot or small-scale project to make it impactful for the target group in a country or industry. The fiscal year 2016–23 gender strategy theory of action includes the buy-in, adaptation, and scaling up of successful approaches to reducing gender inequalities (gender-smart solutions) by the governments and clients. According to the gender strategy, this endogenous scaling up—sustainable and owned by countries and companies—is possible when governments and companies integrate the successful approaches in their own policies and development programs. The strategy provides an example of the Adolescent Girls Initiative, whose approach can be scaled up by governments through its integration in national employment programs.

- The review of stand-alone projects included investment project financing and Programs-for-Results; however, there is no Program-for-Results that is a pilot. Pilot projects represent 50 percent of stand-alone investment project financing and Programs-for-Results. When maternal health projects are excluded, pilots represent 48 percent.