Confronting the Learning Crisis

Chapter 2 | The World Bank’s Global and Regional Analytics and Programs and Global Partnerships

Highlights

In its work at the global and regional levels, the World Bank has recognized the depth of the learning crisis and responded with substantial advisory and analytic work that has provided global public goods related to education system strengthening and capacity development, to measurement of learning and use of data to inform education policy, and to teaching practices.

The World Bank’s regional and global analytic products have diagnosed inequality in access and learning for a variety of marginalized groups. Attention to addressing the adaptations to education delivery to ensure learning for children with disabilities has been modest.

The World Bank has worked strategically and synergistically with partners to convene and build global buy-in for the learning poverty concept, with ambitious goals and targets, helping to focus partners on foundational learning and unified communications on a common message, and has worked with partners to produce a volume of global public goods to respond to the challenges introduced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The World Bank has not systematically evaluated the country-level influence of this work, which creates a critical feedback loop in ensuring that the global and regional products are appropriately suited to country contexts and are creating improvements in education systems, measurement of learning, and teaching practices.

The World Bank’s knowledge and analytic work, partnerships, and global initiatives, as noted in the conceptual framework, can be important contributors to building global knowledge and encouraging action by country clients to support improvements in system alignment and capacity, teaching, and measurement of learning. This chapter, consistent with the conceptual framework, covers the World Bank’s production of global public goods (GPG) and programs to build knowledge and awareness, as well as its actions to translate the GPG into improvements in system alignment and capacity, measurement of learning, and teaching practices by governments.

The World Bank has created a wealth of relevant, high-quality knowledge products. The knowledge portfolio analyzed for this evaluation consists of all 145 ASA products that address basic education, of which 88 are ASA and 57 are impact evaluations classified by the World Bank as global and regional products.1 Equity was a theme analyzed to assess whether the ASA would help countries ensure that children and youth from disadvantaged groups benefit from equitable access to a quality education, consistent with the equity and inclusion aims of the Systems Approach for Better Education Results (SABER). IEG also reviewed a sample of programs and initiatives financed by trust funds (see appendix A), which did not cover all the disadvantaged groups noted in the World Bank ASA.

Increasing Global Knowledge and Building Awareness

The World Bank produced a wealth of knowledge products throughout the evaluated period related to student assessment systems to guide middle- and low-income countries in developing such systems. A conceptual framework created key indicator areas for tracking the development of an effective assessment system, with questionnaires and rubrics to collect and evaluate data on each of the assessment types: classroom assessment, examinations, national learning assessment, and international assessment. SABER–Student Assessment tools were applied in nearly 60 countries, resulting in two regional reports, seven country reports, and case studies of lessons learned from learning assessments and learning standards. Among the many useful, high-quality products that built global knowledge on learning measurement were the following: Primer on Large-Scale Assessments of Educational Achievement (Clarke and Luna-Bazaldua 2021); Map of Country Participation in Regional and International Large-Scale Assessments—Laboratorio Latinoamericano de Evaluación de la Calidad de la Educación, the Programme for the Analysis of Education Systems, the Pacific Islands Literacy and Numeracy Assessment, the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study, the Programme for International Student Assessment, the Southern and Eastern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality, the Southeast Asia Primary Learning Metrics, and the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study; learning standards with questionnaires and rubrics to collect and evaluate data on content, process, and performance standards in language arts, mathematics, and science; and the online course Student Assessment for Policymakers and Practitioners.

This analytic work and the programs and initiatives built global knowledge. A major initiative, SABER, launched in 2011 and continued with various iterations through to its completion in 2020. SABER produced a significant amount of knowledge work focused on specific education policies. Its initial purpose was to help identify and reach consensus on the education policies and programs most likely to create quality learning environments and improve student performance, especially among the disadvantaged, thus filling an important knowledge gap. One hundred countries applied SABER, selecting from among 13 areas of interest (such as school finance, equity and inclusion, and workforce development) with assistance from the World Bank or other development partners to analyze and benchmark their policies and institutions.2

By design, SABER produced comparative data and knowledge on education policies and institutions such that countries could seek to strengthen their systems to support the pursuit of learning for all. For example, the eight policy areas in the SABER–Teachers policy framework address the stock and flow of teachers and were used to diagnose and benchmark countries’ policies to inform government clients and other interested stakeholders and to support dialogue with education ministries and inform project design (World Bank 2018b).3 This aspect of SABER was applied in 36 countries and was used by partner organizations, such as by UNESCO for its Global Education Monitoring Report (UNESCO 2016, 2017). However, it only measured policy intent at the central level and did not assess what was implemented. This tendency to concentrate on the central policy level without strong supplemental attention to implementation and delivery across the system is a feature of the approach at the country level (as discussed in chapter 3).

Several development partners used SABER tools to support global research and their country work, and SABER also informed World Bank operations (World Bank 2018b). For example, SABER–Education Management Information Systems (EMIS) focused on data as a critical element for the education system and on the use of data in decisions by policy makers, school staff, parents, and students. Improved learning requires a functioning EMIS embedded in a strong enabling environment, supported by a well-defined policy framework and organizational structure, with sufficient infrastructure capacity, human resources, and budget—aspects emphasized in the SABER–EMIS framework. SABER–EMIS was implemented in six countries and developed and disseminated additional knowledge products. In addition, an EMIS was a component in numerous World Bank investment projects. Typically, EMIS counted the number of schools, teachers, and students and did not integrate data from the school census or on finances, human resources, learning assessments, or infrastructure. Consistent with the evaluation framework, the success of the EMIS relies on buy-in and collaboration between stakeholders within the education ministry and other relevant agencies. With the evolution in analytic support, EMIS is no longer a feature of the programs and initiatives in the Education GP, even though it is foundational for education systems to influence performance, policy making, planning, and monitoring of results and learning. The absence of a focus on EMIS leaves a gap in the analytic support designed to benefit client countries that still have weaknesses, as further described in chapter 3.

With experience and feedback, SABER’s analytic approach evolved toward systems strengthening and alignment. In time, the focus on policy intent diminished, leading the World Bank to convene an Education Systems Technical Advisory Board in 2017 to gather views on how to enhance the next phase. Based on that feedback, SABER 2.0 evolved to begin developing a framework for measuring and analyzing service delivery at the school level. This effort still left a gap in assessing capacity and coherence at all levels of the education system. The idea was to use SABER tools to provide countries with information to improve their policies and institutions to better meet their education goals; however, scaling up the use of these instruments proved difficult and costly, particularly when governments were asked to finance data collection.

Given the complexity of education systems, a focus on feedback loops is necessary to understand context-specific elements and functions within a system. This implies using existing information and data to identify what is needed to understand the political economy and capacity in that context to create sound, sequenced actions to improve systems that align with government financial resources. Particularly needed is an understanding of the capacity, functioning, and motivation of various actors and agencies that support a teaching career framework (across the stages of recruitment into teaching, preservice institutions, hiring, professional development, motivating, and monitoring) to ensure the system incrementally improves in a manner consistent with higher-performing countries. This information can be used to develop context solutions and a feedback loop so the World Bank can tailor its solutions to a well-understood context.

ASA products have increasingly focused on documenting inequalities in access and learning—an important element of learning for all. These knowledge products (23 out of 88 ASA products and 13 out of 57 impact evaluations) refer to disadvantaged groups, identify risk factors, and propose interventions to improve education outcomes. Groups include school dropouts in Latin America and the Caribbean, refugees and internally displaced persons in the Middle East and North Africa, and out-of-school children and girls in South Asia. In Latin America and the Caribbean, interventions include youth employment training and remedial classes; in the Middle East and North Africa, interventions include psychosocial support and remedial classes. What is particularly needed is moving beyond documenting the number of children with disabilities to provide guidance on adaptations to deliver education that will ensure learning among this diverse and vulnerable group. This type of context-specific evidence fed into the planning and implementation of education systems would be a way to respond to client need.

Sharing Global and Regional Knowledge

The World Bank has shared global knowledge predominantly through workshops, meetings, and policy guidance. The Sixth World Bank Europe and Central Asia Education Conference, supported by Russia Education Aid for Development (READ), helped clients better interpret and communicate learning data with country stakeholders. The team that produced Facing Forward: Schooling for Learning in Africa participated in 10 media events (regional and international); 11 regional or country-level dissemination events with World Bank colleagues and stakeholders; and 3 other events, including with the UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning and the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation ministers of international development. A Country Note prepared for Rwanda distilled the 450-page report into more manageable findings for the client. World Bank documents report that this Country Note helped Rwanda tackle grade repetition. Country Notes were not developed for other countries featured in the report. Box 2.1 summarizes several notable examples of the World Bank generating evidence, disseminating, and engaging in dialogue about policy actions among government clients.

The WDR 2018 benefited from substantial trust fund resources and strong leadership in the GP and Regions to bring further awareness of the need to focus on learning and to align the education system, including the technical, political, and social challenges. Online dissemination of the WDR 2018 is evident in the quantity of people it reached, as it was the second-most-downloaded global report in World Bank history. Findings from the WDR 2018 were presented at 100 dissemination events in 54 countries, particularly low- and middle-income countries, according to World Bank documents. Trust funds also allowed the report and messages to be translated into multiple languages. Practice managers invited members of the WDR team to discussions with finance and education ministry officials, local civil society, and researchers to spur further political commitment. Regions developed context-specific strategic papers that were later discussed with government clients (which is useful to clients).

Box 2.1. Influence of the World Bank’s Regional Advisory Services and Analytics on Country Clients in Developing Projects or Making Policy Reforms

Out-of-School Youth in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Policy Perspective transferred knowledge that enhanced policy dialogue (Inoue et al. 2015). The report brought attention to the needs of 89 million youth (12–24 years of age) who fell through the cracks once they dropped out of school. These youth, many of them living in rural areas, faced a variety of barriers, such as early marriage among girls. The report raised awareness of the problem and offered guidance on how to address it through school retention, educational remediation, and integration of youth into labor markets. The authors of the report disseminated the findings and policy recommendations to government clients in easily digestible form. The report contributed to the development (and financing) of skills development projects in Mali and Niger that focused on in-school and out-of-school youth. This report also resulted in country-specific advisory services and analytics.

The Latin America and the Caribbean Region Teacher Quality Launch Conference presented findings from Great Teachers: How to Raise Student Learning in Latin America and the Caribbean to promote South-South knowledge sharing at the political level with regional ministers of education (Bruns and Luque 2014). The report noted that “the low average quality of LAC [Latin America and the Caribbean] teachers is the binding constraint on the region’s education progress” and that three fundamental steps, “recruiting, grooming, and motivating better teachers,” are essential (Bruns and Luque 2014, 2), but the challenge confronting teacher reform is political. With clients who expressed commitment, further workshops brought together academics, politicians, and technical or other people in government at a seminar in Brazil. The September 2013 seminar sought to build capacity to understand and implement policies and programs that are informed by evidence and tailored to the local context. The study outcomes and dialogue influenced subsequent policy actions to reform teacher status, evaluation, and remuneration in Chile, Peru, and one state of Brazil. However, political changes in Brazil and Peru affected the continuity of the reforms, highlighting the susceptibility of reforms to political influence.

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group interviews and analysis of other World Bank documents; Bruns and Luque 2014; Inoue et al. 2015.

Among the factors that contributed to the World Bank’s influence with country clients were support for follow-up and the ability to link global and regional analytics to country programs. The World Bank provided resources to support staff time not only for dissemination but also for follow-up dialogue to build client support and commitment. In some cases, the evidence was transformed into analytic pieces that were more accessible to country clients. A negative incentive to task teams is that any time spent on influence was not accounted for within the World Bank’s time recording system, according to interviews.

Processes that linked global and regional analytic support with country programs, support, and implementation realities were also key factors in influence. Country clients informed IEG that they valued knowledge tailored to their context, which was similarly found by IEG (World Bank 2013a). Clients who use the World Bank’s ASA find it most effective when it customizes “best practice to local conditions” and formulates “actionable recommendations that fit local administrative and political economy constraints” (World Bank 2013a, 65). Interviews noted tension between the current supply-driven model, which provides evidence, tools, advice, measures, and analyses developed by the Education GP, and the level of interest, demand, and uptake by countries and operational TTLs that support client governments.

Convening and Partnership

The World Bank has worked strategically and synergistically with partners to build global buy-in for learning poverty, which has unified partners in their global message. Through its partnerships, the World Bank has contributed to two important supporting conditions in the conceptual framework. It has built international commitment to improve learning and helped create a coalition of development partners to address the learning crisis. The learning poverty initiative was particularly important in these achievements (box 2.2).

The Foundational Learning Compact also holds promise for improving the availability of essential national assessment data. The World Bank, the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, UNICEF, and other partners have agreed to the Foundational Learning Compact (launched in 2021) to support coordinated efforts to strengthen national assessment systems to ensure that low-income countries have at least one quality measure of learning in two grades and two subjects by 2025 and two measures of learning in two grades and two subjects by 2030. IEG’s review of documents and interviews was not able to identify how many new countries met the goal from the support provided by the Foundational Learning Compact. Going forward, a focus on the 24 countries in the Africa Region that lack a good-quality national assessment and have not participated in international or regional assessments in the past five years is particularly needed, given the global importance placed on learning data (Global Coalition for Foundational Learning 2023).

Box 2.2. Learning Poverty and Its Effect on Global and Country Stakeholders toward Action on the Learning Crisis

The World Bank and the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Institute for Statistics launched the learning poverty initiative in 2019 supported by trust funds and implemented in coordination with many development partners, especially the UNESCO Institute for Statistics and the United Nations Children’s Fund. The World Bank focused its analytic support, building on a comparative strength, to develop consensus among global partners for the validity of learning poverty.a Learning poverty measures both schooling and learning, focusing on reading because it is a requisite skill for other subjects and a proxy for foundational learning. The Learning Poverty Global Database and code book are accessible to the public.b Thus far, learning poverty data are only disaggregated by gender. Although learning poverty was already codified in one of the measures to evaluate progress on Sustainable Development Goal target 4.1, its simplicity and focus enabled stakeholders to unite on a common message. Data to calculate learning poverty are missing in some countries, particularly in Eastern and Southern Africa, where only 29 percent of countries have this indicator. The World Bank, the United Nations Children’s Fund, the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, and UNESCO have prepared joint publications about the status of learning. For example, Ending Learning Poverty: What Will It Take? provided global estimates based on the learning poverty of the low levels of learning, and ambitious global and country targets have been set to motivate global and country stakeholders toward collective action (World Bank 2019b).

Other partners (the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office; the United States Agency for International Development; and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) also use learning poverty, which created a single message from global partners to education stakeholders across the globe. At the end of 2020, the World Bank and partners (the United Nations Children’s Fund; the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office; the United States Agency for International Development; the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; and UNESCO) drew attention to the phenomenon of learning loss, which has become the focus of significant public debate in light of the COVID-19 pandemic,c and The State of Global Learning Poverty: 2022 Update showed the worsening of learning poverty associated with pandemic school closures (World Bank, UNESCO, et al. 2022).

Sources: World Bank 2019b; World Bank, UNESCO, et al. 2022.

Notes:

a. The learning poverty indicator is defined as the share of children in countries who are unable to read and understand a simple text by age 10 years. This indicator brings together schooling and learning indicators.

b. The code is in GitHub; running it allows anyone to generate the outputs (https://github.com/worldbank/LearningPoverty). The output data (Excel file) is in the development data hub (World Bank 2023b). The output country briefs are also public (World Bank 2024a).

c. See, for example, Mervosh (2022).

The World Bank response to the challenges introduced by the COVID-19 pandemic has been characterized by heightened partnership and the formation of new working coalitions and alliances that were established to address immediate needs arising from school closures. There are many examples of important partnership-driven work, including regional partnerships (box 2.3) and larger-scale initiatives. Examples of the latter include the joint approach between the World Bank and the Global Partnership for Education (GPE)—technical assistance, data analysis, and financing—in support of learning continuity and building resilience; the joint surveys and framework on reopening schools developed by the World Bank, UNESCO, and UNICEF; and a joint initiative with the World Health Organization that sought to provide guidance and support to governments on how to safely reopen schools during the pandemic. GPG were developed with GPE financing to provide guidance on school reopening, use of learning assessments in that process, surveys of government education response, the Global Education Recovery Tracker, blogs guiding COVID-19 responses and learning assessments, technological guidance on remote teaching, and methodologies for remote formative assessment of children’s learning. The World Bank joined the UNESCO-led Global Education Coalition—comprising over 200 private sector members, multilateral institutions, nongovernmental organizations, civil society actors, networks and agencies, and international media groups—which is an initiative to support countries’ efforts to mitigate the effects of school closures. The World Bank also partnered with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to help countries implement remote learning solutions, providing technical assistance to education ministries and supporting the development of education technology. The World Bank has also worked with HundrED to develop Technology for Teaching—a program to enhance and increase teacher professional development opportunities using technology-based solutions. However, the use and influence of these global products among country clients have not been evaluated.

More recently, early implementation of the Accelerator Program, which embraces the multidimensionality of basic education systems and the related political and other dynamics associated with learning failure in basic education, suggests some lessons. The program, launched in 2020 by the World Bank and UNICEF (in partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office; the UNESCO Institute for Statistics; and the United States Agency for International Development), “aims to demonstrate that governments that are dedicated to improving their foundational learning outcomes can achieve results within a few years through focused, evidence-based action, with adequate political and financial support” (World Bank 2021a). Accelerator responds to a critical challenge in brokering the supply of GPG—both those produced by the World Bank and those produced by other partners—with the priorities, demands, and needs of individual countries. Although the pandemic delayed progress, the initial stage of implementation suggests that more may be needed to support countries to demonstrate results than what is allowed for in the design of Accelerator. Lessons from leading education systems highlight that sustainable improvement to learning requires concerted reform of key aspects of education systems.4 Interviews have identified issues with waning political commitment as contextual conditions change, suggesting the need for more flexibility in how financing is deployed. Interviews also noted the additional time needed to coordinate among partners and clients.

Box 2.3. Regional Partnerships’ Help with Identification of Issues Contributing to Low Learning

Nonlending technical assistance provided to Papua New Guinea, Tonga, and Vanuatu introduced an Early Grade Reading Assessment (EGRA). Partners of the World Bank included Fast Track Initiative, the Australian Agency for International Development, and the New Zealand Aid Programme, which together produced baselines of EGRA performance for each country during the 2009 and 2010 school years. They also built local capacity to replicate EGRA in each country and worked with each country and partners to interpret assessment findings and analyze their policy and investment implications. The assessments in Tonga and Vanuatu identified the issues underlying low learning and created an agenda for common action among partners. The crucial issues related to the large share of unqualified teachers, lack of exposure to print material, and classroom instruction not conducted in students’ native language. Partners aligned and coordinated work to support phonics instruction. The analytic work informed policy dialogue that resulted in curricular reforms in the lower primary grade. It also supported training for government staff to design and administer EGRA. Interviewees praised the success of this technical support for its high technical quality, but documents also noted implementation weaknesses by the World Bank related to timeliness and dissemination of results to the client (which were due to constraints in staff availability to respond).

Source: Analysis of World Bank documents and Independent Evaluation Group interviews.

Feedback Process to Strengthen Systems, Teaching, and Learning

The World Bank has not systematically evaluated the influence and use of ASA products in client countries and therefore lacks a feedback mechanism consistent with the conceptual framework to assess the intermediate outcomes in country clients. The World Bank’s internal reporting of outputs lacks systematic and rigorous evaluation of the influence and impact of its ASA and sometimes lacks outcome measures to support assessment. The World Bank should not be satisfied with tracking the number of countries that implement its tools and should seek evidence of sustainable changes, as was the case with the second phase of READ, which reported on baselines, targets, and achievements of capacity against various performance indicators. The efficacy of tools and programs also needs to be evaluated to ensure that they are resulting in improvements in systems, teaching, and measurement of learning. For example, expanding the evidence base of the efficacy of Teach and Coach to improve teaching practices and student learning is needed beyond what currently is reported.5

Reports prepared for donors of trust funds describe delivery of outputs but lack reporting of outcomes achieved with the transmission of knowledge or technical assistance. IEG has previously found that global and regional ASA should be subject to a similar self-evaluation process to financial projects (World Bank 2022b), as this is a shortcoming not just of the Education GP. Despite asking for stories of impact of GPG or partnerships during IEG’s interview, the evaluation was able to capture only examples of dissemination, and few respondents were able to tell IEG what happened as a result. As the framework highlights, the World Bank will need to move beyond its current focus on production and sharing to ensure that the uptake with clients results in actions to improve systems, teaching, and measurement of learning and to ensure increases in the availability of disaggregated learning data. A theory of change can facilitate planning for implementation and monitoring of how client governments use global and regional analytics. This change is aligned with the World Bank’s Knowledge Compact for Action: Transforming Ideas into Development Impact (World Bank 2024b), which will require stronger monitoring to provide a feedback loop to the World Bank (box 2.4).

Box 2.4. The Foundational Learning Compact Lacking Outcome Measures

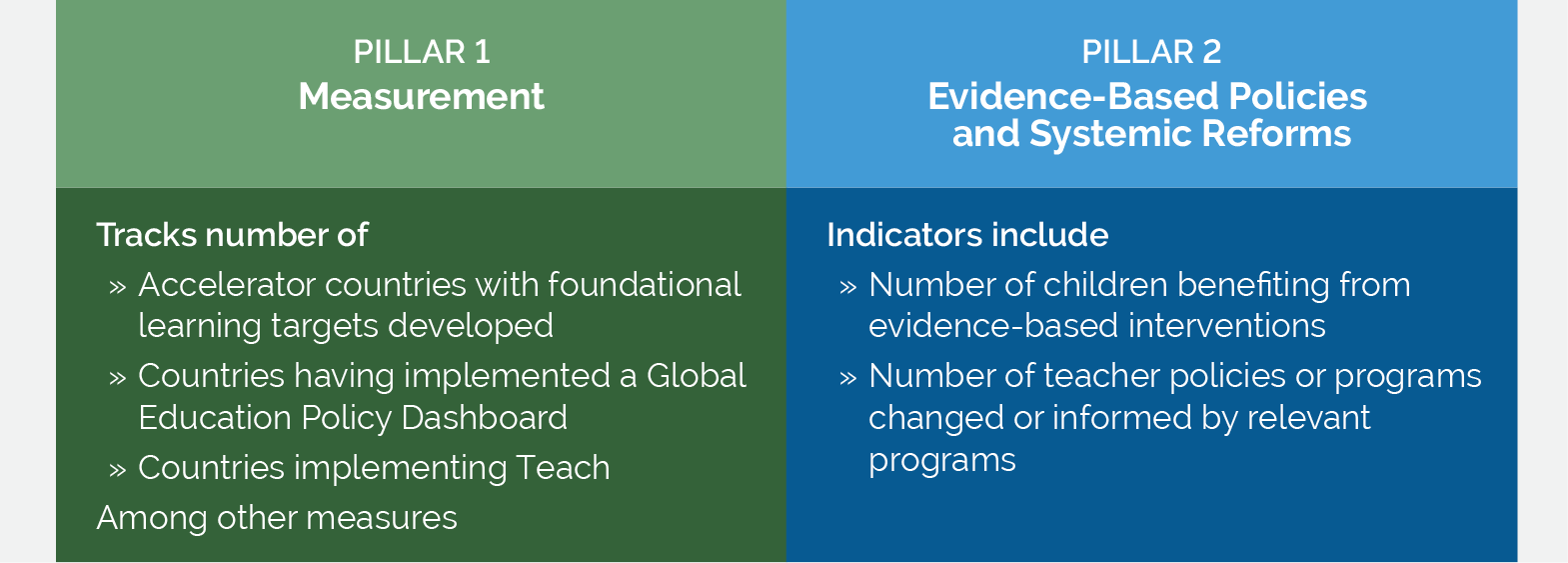

The Foundational Learning Compact trust fund provides financing for various initiatives in the Education Global Practice, including Coach, Teach, the Accelerator Program, and the Learning Compact, which were separately funded by various donors before being housed under a single umbrella mechanism. The Concept Note for the Foundational Learning Compact states that its objective is to enhance global and country efforts to pursue systemic and sustained improvements to early childhood, primary, and secondary education systems to achieve learning for all. The higher-level objectives include reducing learning poverty and increasing learning-adjusted years of schooling. The results framework, built on two pillars (figure B2.4.1), does not feature any outcome indicators or explicitly link the path of the World Bank’s actions to changes in clients—for example, moving beyond tracking the number of countries where policy dialogue is informed by the work of the Foundational Learning Compact. Independent Evaluation Group interviews similarly reported the gap in rigor in the results chain and the lack of outcome measures.

Figure B2.4.1. Results Framework for the Foundational Learning Compact Trust Fund

Source: Independent Evaluation Group based on Concept Note and interviews.

- Advisory services and analytics products are coded based on the project identification number and may contain multiple outputs.

- Between 2010 and 2017, the application of the Systems Approach for Better Education Results 1.0 produced 13 framework papers, 11 domain tools, more than 190 country reports, five global or regional analyses, and more than 50 case studies and background papers.

- The policy areas in the Teachers policy framework were as follows: setting clear expectations for teachers, attracting the best candidates into teaching, preparing teachers with useful training and experience, matching teachers’ skills with students’ needs, leading teachers with strong principals, monitoring teaching and learning, supporting teachers to improve instruction, and motivating teachers to perform.

- For example, leading systems select and encourage teachers to grow in their careers (Schleicher 2018). NCEE’s Blueprint for a High-Performing Education System highlights attention to reforms focused on systems (capacity and coherence across levels), measurement of learning, teaching, and focus on equity (NCEE 2021).

- The World Bank plans for further evaluation but reports that Teach is linked to higher student achievement in language and mathematics. It has also explored the extent to which raters or enumerators contributed to Teach score bias, finding that the scores produced by the classroom observation tool are mostly the product of the aspects of teacher quality measured by each of its items and the teacher performance, rather than the product of enumerator bias.