Making Waves

Chapter 3 | The World Bank’s Operationalization of the Blue Economy

Highlights

The governments of case study countries are just beginning to establish coherent policy, strategy, and institutional mechanisms for effective blue economy development.

The World Bank relevantly identified and addressed policy and institutional issues in the Eastern Caribbean to help harmonize and develop blue economy policies and practices. Elsewhere, the World Bank has mainly used sector entry points that are achieving sector results but are not being leveraged to support policy and institutional development critical for achieving blue economy aims.

There have been missed opportunities to support blue economy development after the World Bank launched influential analytics at the country level. Engagement challenges are associated with the limited number of staff with blue economy expertise, staff rotations, and a lack of Country Management Unit buy-in for the concept.

The World Bank has helped strengthen sector platforms at the regional level, but these efforts have yet to use a blue economy approach to identify cross-sector opportunities and address sector trade-offs. There have been missed opportunities to support regional bodies that are developing blue economy strategies. Where the World Bank has partnered regionally, its support has also sometimes been out of step with organizations’ capacities and mandates.

The designs of small-scale fisheries projects are increasingly aligned with progressive global fisheries guidance that is capable of achieving blue economy aims. Consistent application of this guidance can promote more holistic designs for some projects that retain a growth aim and the enhanced integration of climate change considerations.

The World Bank’s global plastics analytics and estimation models are being used by policy makers to tackle plastic pollution. The World Bank has used development policy lending to address marine plastics issues in small island developing states, but this policy support has yet to be extended to coastal nations that rank as major contributors to plastic waste production.

The World Bank’s blue tourism paper can support more holistic tourism approaches in marine and coastal tourism operations that contribute to local economic development and jobs, but with few exceptions, these operations pay insufficient attention to upstream environmental issues, such as water use and waste.

Aspects of the blue economy in the marine transport space—such as decarbonization and greening of ports—have been covered in analytics, but operational uptake is low.

PROBLUE has been instrumental in helping the World Bank produce blue economy analyses within advisory and operations. PROBLUE has had a pronounced focus on marine pollution with increasing thematic diversification in line with blue economy aims. PROBLUE funds are just beginning to finance blue economy activities in investments outside of the environment sector. PROBLUE promotes gender integration in its grant applications, but targeted gender expertise is needed in operations to ensure gender outcomes are achieved and measured.

This chapter focuses on how well the World Bank is operationalizing blue economy aims at the country, regional, sector, and corporate levels. At the country and regional levels, we assess how well the World Bank is supporting enabling conditions—policies, institutions, planning, and blue bonds—for blue economy development by presenting cross-cutting evidence from the nine case studies. At the sector level, we then present the findings of our portfolio review analyses to show how well the World Bank is adapting its approach in four established sectors—small-scale fisheries, plastics and marine pollution, marine and coastal tourism, and maritime transport—to achieve blue economy aims. At the corporate level, we assess the extent to which the PROBLUE trust fund has supported the integration of the blue economy across sectors.

Enabling Blue Economy Development at the Country Level

Policy and Institutions

The governments of all case study countries are just beginning to establish coherent policy, strategy, and institutional mechanisms for effective blue economy development. The World Bank’s global blue economy analytics cite the need for the World Bank to act upstream to identify and address the governance and institutional issues required to achieve blue economy aims (Patil et al. 2016; World Bank 2021d). This need to act upstream is because policies governing ocean and coastal resources are fragmented and characterized by legal, regulatory, and jurisdictional gaps (Patil et al. 2016; World Bank 2021d). Ministries often have overlapping mandates on the blue economy and few incentives to cooperate, rather than compete, for control over relevant sectors. For example, Belize has at least 16 different laws and regulations directly affecting the management of the country’s coastal and marine areas that need to be reconciled as part of the government’s blue economy policy development aims. In addition, Belize’s newly established Ministry of Blue Economy and Civil Aviation brings together some institutions responsible for the ocean economy, including the Fisheries Department and the Coastal Zone Management Authority and Institute, but not others, such as marine and coastal tourism and mangrove management managed by the Forest Department. In Bangladesh, there is a lack of consensus on the institutional leadership of the blue economy despite the creation of a blue economy cell within the Ministry of Power, Energy and Mineral Resources, leading to power struggles among different ministries. In Cabo Verde, the Ministry of the Sea and the Ministry of Tourism and Transport have not agreed on who is responsible for tourism under a blue economy framing. In the Seychelles, the Tourism Department has not been included in the blue economy development process that has mainly focused on blue finance and fish. In India and Kenya, even though national ministries have important regulatory, monitoring, and guiding policy functions, they do not have a role in policy implementation, which is decentralized to the state and local governments.

The World Bank relevantly identified and addressed policy and institutional issues in the Eastern Caribbean to enable the harmonization and development of blue economy policies and practices. Funded by the Global Environment Facility, the World Bank’s Caribbean Regional Oceanscape Project (CROP 2017–21)—which covered Dominica, Grenada, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines—achieved its aim of strengthening capacity for ocean governance. Although the Eastern Caribbean states had indigenously put forth the St. George’s Declaration of Principles for Environmental Sustainability in the OECS—the existing vision of the blue economy in the OECS—support was needed to translate that vision into regional and national policies, produce national asset accounts, and harmonize and update sector legislation. CROP supported, in a participatory manner, the development of regional and national marine spatial plans (endorsed at ministerial levels), national ocean governance committees, and regional and national ocean governance policies and laws (including model national fisheries and pollution laws) needed to achieve effective blue economy development.1 The marine spatial planning (MSP) processes helped identify and prioritize blue economy investments in line with shared principles. Although no private investment was forthcoming, these processes helped mobilize other donor financing (Irish and Norwegian) and informed the development of a blue economy–focused development policy financing series to address marine pollution, among other aims. CROP’s focus on governance and data-driven decision-making was, as articulated in the Implementation Completion and Results Report, “a model to emulate” (World Bank 2022b).

With few exceptions, the World Bank has mainly used sectoral entry points that have not been sufficiently leveraged to support blue economy policy and institutional development. The World Bank has seized opportunities to engage in sector operations that can have a positive effect on the blue economy; however, in most cases, it has not seized the opportunity to leverage these sector operations to engage on blue economy policy or institutional development. In Belize, the World Bank’s 2012 technical assistance cites opportunities offered by the development of a blue economy approach, but the World Bank did not use its subsequent Marine Conservation and Climate Adaptation Project (2015–20) as an entry point to engage with the government on blue economy development. The Marine Conservation and Climate Adaptation Project was under implementation when the World Bank rolled out its blue economy agenda. A problem that arose during the Marine Conservation and Climate Adaptation Project was the displacement of fishers because of expansion of protected areas supported by the project—a problem that could have been prevented, or solved, using a blue economy approach. In Kenya, the World Bank has engaged in fisheries operations, which are achieving enhanced local fisheries management (including through spatial planning) and community livelihoods, but not on blue economy strategy or institutional development. Our cabinet-level interviews confirmed that the Kenyan government needs support from donors to help address gaps (for example, participation, sector coverage, and gender gaps) in the development of their draft blue economy strategy and its implementation, especially in coastal counties receiving support from the World Bank’s fisheries operation. In Indonesia, the World Bank has made and continues to make important contributions to biodiversity protection, carbon storage, and social welfare through the Coral Reef Rehabilitation and Management Project (2004–present) and the Mangroves for Coastal Resilience Project (2022–present), but it has not engaged on blue economy policy development. The challenge in Indonesia is that the World Bank is effectively engaging with the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries, but the Blue Economy Roadmap is being rolled out by the Ministry of National Development Planning through a process that has minimal consultation and that is opaque about ecological and social considerations in relation to its blue growth aims. In Cabo Verde, the World Bank has engaged in tourism and fisheries through the Resilient Tourism and Blue Economy Development in Cabo Verde Project (2022–present), which seeks to relevantly achieve sector synergies by improving the quality and diversity of local fish for the tourism sector and by improving market and credit access for the fisheries sector. It is also financing a development policy financing series for Cabo Verde’s Resilient and Equitable Recovery (2022–24) that supports zoning, licensing, and other regulatory aims but that has dropped a prior action related to MSP integral to achieving higher-order blue economy policy aims. In Morocco, the World Bank is supporting a blue economy Program-for-Results that is focused on developing institutional frameworks to improve the integrated management of natural resources in line with blue economy aims.

Critical gaps between the launch of influential blue economy analytics and operational support have also hindered blue economy development. Across all the case study countries, World Bank analytic work on the blue economy, funded by PROBLUE or other trust funds, is well regarded by clients and has often been key to shaping the blue economy narrative.2 However, progress in taking forward this diagnostic and analytic work in blue economy policies and strategies either has stalled or has not been reinforced after initial engagements are completed. For example, in Bangladesh, the World Bank and the European Union helped the government develop a blue economy strategy between 2016 and 2018, including by facilitating awareness across ministries. After the departure of a key World Bank staff member, the blue economy development process has stalled. Although members of the government have a general understanding of the blue economy concept, it is loosely articulated regarding the development of coastal sectors without the spatial dimension, with limited cross-sector coordination and no real appreciation of the triple bottom line. Recognizing the need to rekindle dialogue, the World Bank country office formed a blue economy team in 2023, but it is taking time to gain traction. A similar situation occurred in Sri Lanka after the launch in 2017 of Managing Natural Wealth for Resilient Growth and Livelihoods: Unleashing the Potential of the Blue Economy. In the OECS, although the World Bank effectively supported blue economy policy and institutional development through CROP at the regional level, it prematurely transitioned from a focus on broader blue economy governance to national sector-level investments (waste management, tourism, and fish) and associated sectoral policy development in the follow-on investment operation. Although sector investment at the country level is necessary, the governance elements of CROP associated with the foundations of the blue economy needed reinforcement because the national policies and governance committees resulting from CROP have yet to be endorsed, formally adopted, and implemented by governments. Maintaining country engagement is important because the blue economy approach requires a strong shift in practices and mentalities and often involves policy and institutional reforms that can face resistance. Engagement challenges are associated with the limited number of staff with blue economy expertise, staff rotations, and Country Management Unit buy-in for the concept.

Integrated Coastal Zone Management and Marine Spatial Planning

The World Bank is not sufficiently leveraging its experience with integrated coastal zone management (ICZM) to support inclusive blue economy development. A sustainable blue economy calls for a strategic, integrated, and participatory approach to planning and managing coastal and marine areas. The World Bank was an early adopter of ICZM—a bottom-up, inclusive, and iterative governance approach to coastal development implemented by regional or local governments with wide stakeholder participation. ICZM institutes legal and institutional mechanisms to ensure that coastal development supports environmental and social goals and minimizes conflict (European Commission 1991; European Parliament and Council of the European Union 2002; Post and Lundin 1996). The World Bank published its ICZM guidelines in 1996 to guide its operational work (Post and Lundin 1996), including in nine lending activities in Albania, Belize, Egypt, India, Kenya, Morocco, Namibia, West Africa, and Viet Nam, implemented during the evaluation period (of which seven are closed and two are near closure). In all projects, ICZM has, to varying extents, improved coastal management by resolving policy and institutional and jurisdictional issues and achieved environmental and social benefits, including coastal land and resource restoration, pollution reduction, job creation and increases in local incomes, and more stable coastal environments conducive to private investment.3 Yet, whereas Riding the Blue Wave: Applying the Blue Economy Approach to World Bank Operations (World Bank 2021d) refers to ICZM as an important blue economy tool, the World Bank has not updated its guidance in almost 30 years; with two exceptions (Viet Nam and West Africa), no new lending in coastal areas since 2018 incorporates ICZM tools. Rather, in other projects, the World Bank is supporting a version of MSP that is top-down, focused on investment planning (as indicated in its 2022 MSP tool kit), and that often primarily centers on the fisheries sector. This is the case, for example, in Kenya and Morocco, where the World Bank has not created effective links or alignment between ICZM and MSP approaches. The literature indicates that ICZM and MSP need to come together for sustainable blue economy development. The Independent Evaluation Group, however, identified only one project that creates explicit links between these two approaches (in Viet Nam; see box 3.1).

Box 3.1. Linking Integrated Coastal Zone Management and Marine Spatial Planning Processes to Ensure the Success of the Blue Economy

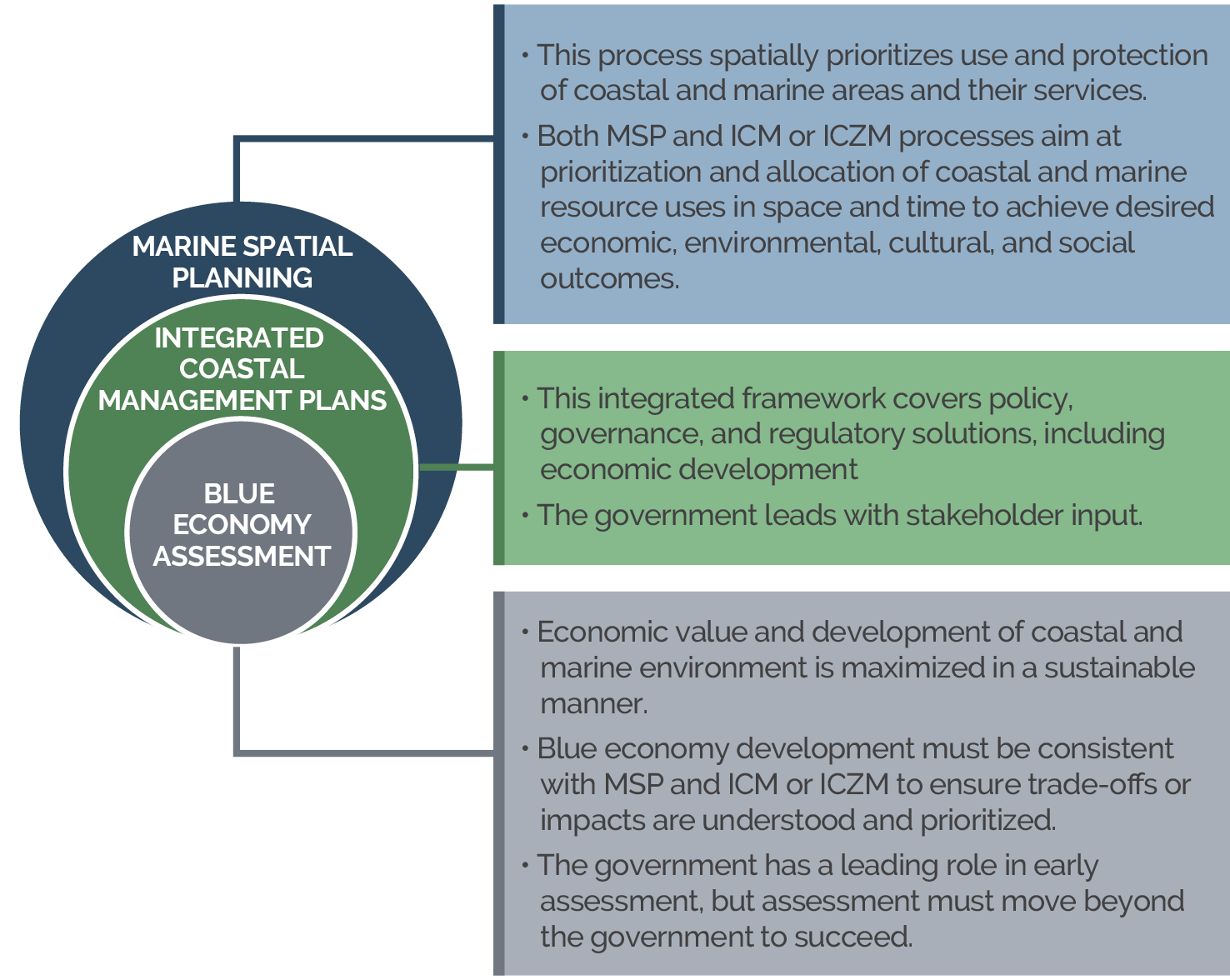

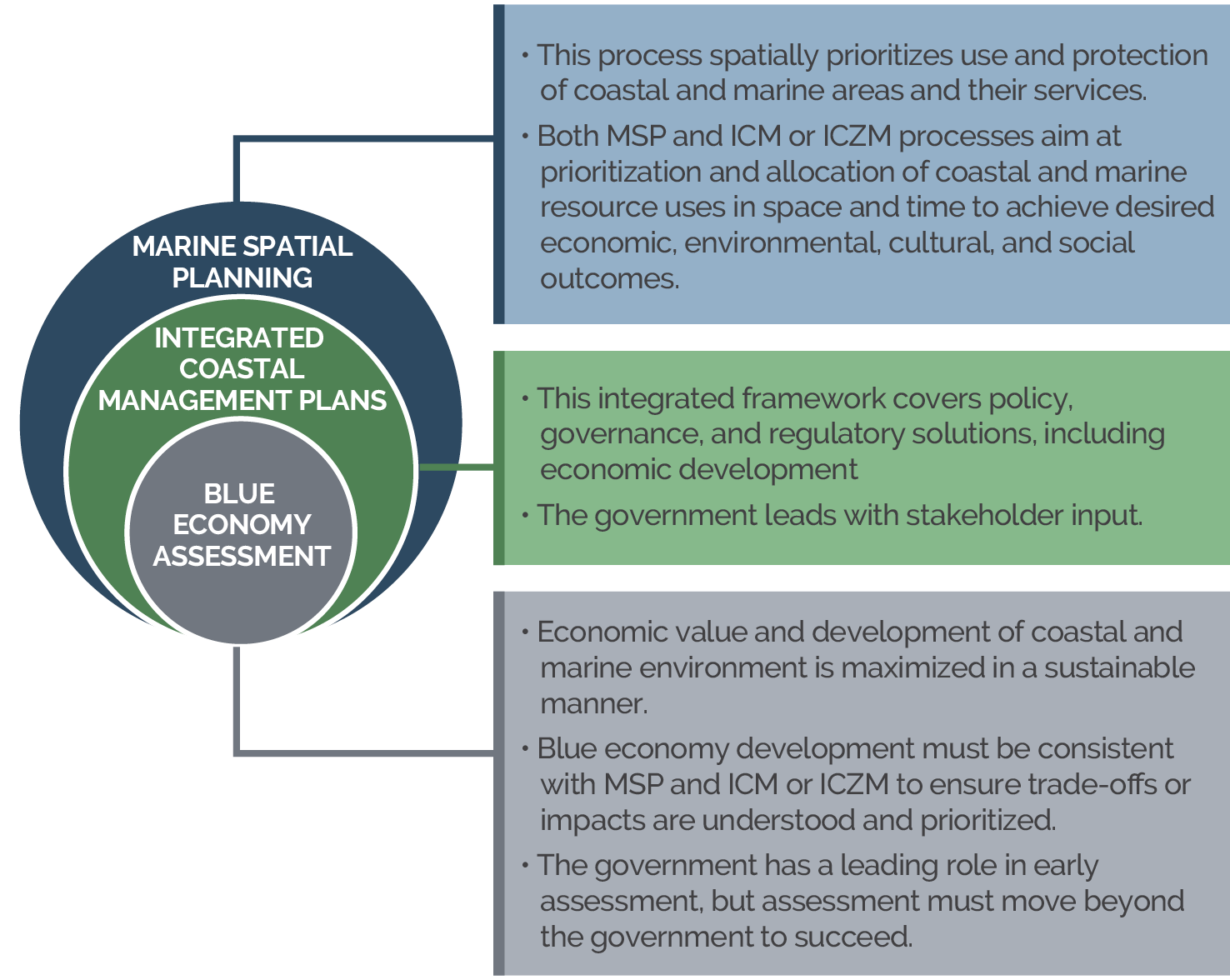

In Viet Nam, through the programmatic advisory services and analytics (Enhancing Environmental Sustainability and Resilience, 2018–22), the World Bank has articulated how to use both integrated coastal zone management (ICZM) and marine spatial planning (MSP) approaches to support blue economy development. As depicted in a report produced by the World Bank’s advisory services and analytics (figure B3.1.1), the success of the blue economy depends on effective planning, identification, and management of trade-offs at multiple levels to achieve desired economic, environmental, and social outcomes.

Figure B3.1.1. Alignment between MSP and ICZM in Viet Nam’s Blue Economy

Source: Adapted from World Bank 2022h.Note: ICM = integrated coastal management; ICZM = integrated coastal zone management; MSP = marine spatial planning.

In Morocco, the World Bank effectively piloted the ICZM approach at the local level through a Global Environment Facility project (2012–17), and supported ICZM policies and regional coastal plans through the Green Growth development policy financing series (2014–16) and technical assistance (2020). The Global Environment Facility pilot demonstrated the successful application of the ICZM approach by integrating ICZM in local development plans and piloting investments in coastal resource management, which helped restore 500 hectares of land and created local jobs with sustained income benefits. The development policy financing series supported the approval of the coastal law and legislation on illegal fishing, and the technical assistance helped prepare the first regional coastal plan (in Rabat-Salé-Kénitra). More recently, the World Bank has supported MSP by training the government in MSP approaches and providing technical assistance to the Maritime Fisheries Department to use MSP in the creation of a marine protected area for fisheries management in the Souss-Massa region. However, having the pilot led by one sectoral ministry and focusing primarily on one sector (fisheries) deviates from the more multidisciplinary and integrated ICZM approach.

In Kenya’s coastal counties, the World Bank used an ICZM approach (in the Kenya Coastal Development Project, 2011–17) to support sustainable fisheries management, with a focus on increasing incomes and effective natural resource management. The project used integrated conservation and land use plans—a participatory planning mechanism implemented at the local level—to increase awareness and influence behavior for enhanced fisheries and natural resource management. In a follow-on project, the Kenya Marine Fisheries and Socio-Economic Development Project (2020–present) continues to focus on community welfare, through fisheries co-management arrangements, while also supporting national MSP. The latter effort discontinues work on integrated conservation and land use planning and does not make explicit how local planning processes will feed into national MSP and decision-making. This is especially important in a country like Kenya, whose constitution devolves responsibilities for coastal development to the local level.

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group; World Bank 2022h.

The World Bank’s First Blue Bond

The world’s first blue bond (supported by the World Bank in the Seychelles) brought blue finance to the global stage but does little to demonstrate how capital markets can support the development of the blue economy. The Seychelles issued the first sovereign blue bond of $15 million in 2018, facilitated by the World Bank. The World Bank defines a blue bond as “a debt instrument issued by governments, development banks[,] or others to raise capital from impact investors to finance marine and ocean-based projects that have positive environmental, economic[,] and climate benefits” (World Bank 2018c). The objective of the blue bond, according to project documentation, is to demonstrate the potential for countries to harness capital markets for financing the sustainable and inclusive use and protection of marine resources. But the bond depended significantly on a World Bank partial guarantee of $5 million and a highly concessional $5 million loan from the Global Environment Facility Non-Grant Instrument Pilot. Therefore, although a highly innovative but concessional Blue Grants Fund was effective in piloting sustainable marine activities (for example, seaweed cultivation, oyster farming, pollution abatement, research and conservation activities), the effectiveness of the bond’s loan component (the Blue Investment Fund) was negatively affected by a lack of local investors, due in part to high collateral and substantial down payment requirements. The fund is supporting an established investor in the fisheries sector but not other diversified sustainable blue economy opportunities, such as those piloted through the grants. The scale of the fund also likely limited the participation of mainstream institutional investors, who typically seek different incentive structures. The monitoring and compliance management framework is also not sufficient to ensure that the bond remains aligned with blue economy objectives and sustainability principles (March et al. 2024).

Enabling Blue Economy Development at the Regional Level

The varying mandates and capacities of regional organizations have been a key determinant of success for blue economy development, especially in the context of the OECS. The World Bank’s support for blue economy development in the Eastern Caribbean was effective because the OECS—the regional implementing body for CROP—has high technical capacity in the area of the blue economy, long-standing relationships with member states, and a wide remit (extending to environmental, health, social, and economic policy areas). Furthermore, the homogeneity of the Eastern Caribbean islands makes managing opportunities and trade-offs relatively consistent. This example stands in stark contrast to the Pacific Islands Regional Oceanscape Program, where project implementation arrangements called on Forum Fisheries Agency—a regional fisheries body—to take on governance activities necessary for blue economy development that went beyond their technical mandate.

Although the World Bank has helped strengthen sector platforms at the regional level, these efforts have not yet introduced a blue economy lens. The World Bank has worked to build or strengthen regional platforms— including the West Africa Coastal Areas Management Program in West Africa and regional fisheries bodies through the West Africa Regional Fisheries Program, South West Indian Ocean Fisheries Governance and Shared Growth, and Pacific Islands Regional Oceanscape Program—and to help strengthen the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ capacity for addressing marine plastics. Although these platforms do not have an official mandate to engage in the various sectors that fall under the blue economy approach, the World Bank’s support could be anchored in a blue economy lens to promote coordination and coherence—and to identify opportunities—between the disparate agendas (between fisheries, coastal resilience, marine plastic pollution, and so on).

There have also been missed opportunities to support regional bodies developing blue economy strategies. The landscape of regional organizations influencing the blue economy is complex. Influenced by regional political dynamics, these organizations include economic unions, fisheries management organizations, and ocean governance bodies. In Africa, there are several regional bodies that are contemporaneously developing blue economy strategies. These include the African Union Interafrican Bureau for Animal Resources, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, and the East African Community. The evaluation found that each organization is prioritizing a subset of blue economy aims in their strategies rather than balancing these aims and that members would welcome World Bank support for knowledge sharing, strategy harmonization, and capacity building for blue economy policy development but that this aid has not been forthcoming.4

In cases where the World Bank partners with regional organizations influential to the blue economy, its support has sometimes been out of step with the organizations’ capacities and mandates. As discussed, in the Pacific, the World Bank ineffectively engaged a regional fisheries organization to address ocean governance issues, a remit that exceeded its mandate. Conversely, although the Indian Ocean Commission in the southwest Indian Ocean has a comprehensive understanding of the blue economy and capacity to facilitate effective knowledge sharing among member countries, the World Bank relied on it to deliver regional fisheries activities that exceeded its sector technical capacity, and thus the project has underdelivered.

Adapting Established Sectors to Achieve Blue Economy Aims

Blue economy development requires traditional sectors to transition away from unsustainable approaches toward activities that seek to achieve a triple bottom line. Blue economy development calls for transitions in coastal and oceanic sectors, requiring “new practices and approaches that can both enhance the sustainability of these sectors and limit, to the extent possible, the negative impacts they have on ocean health” (World Bank 2021d, 18). It also requires policies that actively seek out opportunities for sector synergies that maximize benefits and address trade-offs. For example, in the Philippines, efforts to protect and restore mangroves have helped rejuvenate fish stocks while protecting elements of the country’s pearl industry from the negative effects of disasters caused by natural hazards. We use a review of relevant literature (including internal and external publications) to understand and explain the challenges facing four key sectors within the blue economy—small-scale fisheries, plastics and marine pollution, marine and coastal tourism, and maritime transport infrastructure—and, relatedly, the way a blue economy approach is envisioned to address these. We then use portfolio review analyses to review the World Bank sector portfolios (ASA and lending), where we examine sector results and the extent to which sectors are transforming in line with blue economy principles.

Small-Scale Fisheries

Capture fisheries are essential to the well-being of millions of vulnerable households spread across most coastal nations. However, globally, fish stocks are massively depleted. Fisheries contribute to food and nutrition security, employment, and economic development (Chuenpagdee and Kerezi 2022; Neiland et al. 2016) and can produce comparatively low-carbon protein for human consumption (Parker et al. 2018). In many regions, small-scale fisheries are fundamental, providing affordable protein and micronutrients that are difficult to replicate (Arthur et al. 2022), and they can be the buffer between precarious livelihoods and destitution (Belhabib, Sumaila, and Pauly 2015). Economic benefits extend for hundreds of miles along trading routes locally and globally. For example, small-scale fisheries represent 40 percent of global seafood capture, employ 90 percent of the sector’s workforce, and are critical for improving gender equity because women make up 50 percent of the postharvest labor force—for example, processing, transport, sales, and so on (FAO, Duke University, and WorldFish 2023). However, between 30 and 35 percent of fish stocks globally remain overfished, and about 60 percent are fully fished with no potential for increased production (Link and Watson 2019; Ye and Gutierrez 2017). Small-scale fisheries in lower- and middle-income countries struggle to maintain their existence and are vulnerable to climate change (Chuenpagdee and Jentoft 2018; World Bank 2019a).

Investment in fisheries management is beneficial and necessary, but enabling sustainable fishing is complex and requires a blue economy approach. Effective fisheries management can lead to sustainable fisheries (Hilborn et al. 2020), and investment in improved fisheries outcomes will increase resilience and reduce poverty. Progress takes time, however, as the causes of unsustainability are myriad and connected. Poverty, political and economic marginalization, depleted stocks and habitats, competition for space, and, in some cases, corruption are common contributing factors (Chuenpagdee and Jentoft 2018). Progress, therefore, requires multiple factors to be addressed, including factors beyond the remit of traditional fisheries management. Fisheries, sustainability requires cross-sectoral alignment that emphasizes sustainable development, social inclusion, and environmental recovery—in other words, a blue economy approach.

Where fisheries are unsustainable, progress will involve managing trade-offs. Although fish stock health depends on the wider environment, the activity of fishing is often a primary driver of depletion (IPBES 2019). Shifting trajectories from unsustainable to sustainable involves transferring short- to medium-term costs onto those most dependent on the fished resources (Bladon, Greig, and Okamura 2022). Hence, management measures and interventions that restrict fishing are often resisted and are politically sensitive (Oyanedel, Gelcich, and Milner-Gulland 2020). Interventions need to seek sustainability across all outcomes—ecological, economic, and social—which may require social protection and labor instruments to compensate for costs and to incentivize behavioral change (Bladon, Greig, and Okamura 2022).

The World Bank has supported a steady stream of analytics and lending in the fisheries sector, which is the subject of this assessment. The World Bank provided 43 ASA and lending projects focused on fisheries development between 2016 and 2023. There were 13 ASA and technical assistance products that included fisheries analyses, of which 8 were completed and 5 are ongoing, and 39 lending projects with a focus or co-focus on fisheries (including 36 investment project financing, 2 development policy financing, and 1 Program-for-Results), of which 12 were closed and 27 are active. Projects were widely dispersed geographically, with most projects located in the East Asia and Pacific, Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Middle East and North Africa Regions.

The World Bank has put forth progressive global fisheries management guidance capable of supporting the blue economy goals that is increasingly reflected in the design of investments projects focused on small-scale fisheries. The World Bank published a new Fisheries Sector Assessment Toolkit in 2021 that progressively and explicitly includes social, ecological, and economic criteria and that has the potential to improve the treatment of resource sustainability and social protection, alongside economic development, in sector operations. This guidance is reflected in analytic support in Myanmar (2020–21), where the World Bank progressively set out to make a business case for improved fisheries governance, promoting good fisheries management as a means of fostering sustainable and inclusive growth. Projects in Peru (2017–23), Bangladesh (2019–present), Liberia (2022–present), Indonesia (2023–present), the Philippines (2023–present), and Senegal (2023–present) provide additional examples of fisheries projects that are transforming to include a blue economy focus or that better align with blue economy principles. For example, in Senegal, focal areas include intersectoral collaboration, resource resilience, and more inclusive governance, and in the Philippines, fisheries management, diversified livelihoods, conservation, and climate resilience feature. In Madagascar (2017–24), social protection features strongly as a means of offsetting overfishing challenges.

Consistent application of the World Bank’s Fisheries Sector Assessment Toolkit could promote more consistent and holistic treatment of sector issues and equal consideration of social, ecological, and economic outcomes in the ongoing and future portfolio. Some projects focused on small-scale fisheries and aquaculture that have been concurrently approved are not well aligned with holistic blue economy aims. In Sri Lanka (2020–21), fisheries analytics were focused on increased production in a sector where resource sustainability is a concern (IOTC 2022). Investments in Grenada and St. Vincent and the Grenadines (2017–present), Kiribati (2018–19), and India (2022–present) that support fisheries and aquaculture expansion do not articulate how they will address overfishing and resource scarcity.

Consistent application of the World Bank’s Fisheries Sector Assessment Toolkit can also support enhanced considerations of climate change. Climate change risks are discussed in all Project Appraisal Documents, but explicit climate resilience measures featured in only 40 percent of them.

The World Bank is also not sufficiently testing its assumptions about fisher behavior as part of a wider blue economy approach. Blue economy development requires an assessment of trade-offs (between biodiversity and climate change goals and marine resource extraction, for example) and a consideration of how to compensate vulnerable resource users under changing circumstances. Of small-scale fisheries lending operations, 75 percent include livelihood components. A key assumption associated with the design of these components is that fishing pressure can be reduced by offering income-generating opportunities (outside of fishing, such as in tourism, agriculture, or agroforestry), alongside other management efforts. However, these project theories are ambiguous as to whether they intend to have fishers shift completely away from fishing to alternative forms of economic activity or to have them fish less while supplementing their income. This distinction is important because experience shows that it can be quite difficult to move individuals who have engaged in catch fishing as their primary form of livelihood away from fishing on a permanent basis (Crawford 2002). World Bank projects measure participation rates, but less than half measure economic outcomes from livelihood activities, and none specifically assess the links between these livelihood activities and marine resource health (for example, reduced pressure on the ecosystem, fish stocks, and so on), including through studies. The World Bank’s causal theory in this space needs to be tested because studies show the following:

- Even if workers are successful in acquiring skills to engage in new sectors, they may diversify their livelihood activities without reducing fishing (Brugère, Holvoet, and Allison 2008).

- Small-scale fishing is tied to identity and self-worth—individuals may not be willing to exit because of stock declines, even when equal or better opportunities are available (Blythe 2015; Knudsen 2016; Muallil et al. 2011; Pollnac, Pomeroy, and Harkes 2001).

- Additional sources of income have enhanced the well-being of fishers, but they also contribute to additional pressure on nearshore resources (Epstein et al. 2022) and can reduce the likelihood of fishery exit in the long term (Slater, Napigkit, and Stead 2013).

- Diversification reduces the risk of livelihood failure; thus, it can supplement and complement fishing activity that might not otherwise be economically viable because of factors such as seasonality or lack of credit (Allison and Ellis 2001).

- Fishing is an enjoyable leisure activity for many, and increased income from alternative sources can increase the availability of time to engage in fishing (Reddy et al. 2013; Walsh, Groves, and Nagavarapu 2010).

Plastics and Marine Pollution

Marine plastic pollution is a chronic global problem that has reached a crisis level, with effects that are compromising ocean and human health and the potential of the blue economy. The productivity, viability, profitability, and safety of key blue economy sectors, including fishing, aquaculture, tourism, and heritage, are all diminished by plastic pollution, with coastal communities particularly vulnerable to the social and economic effects of marine plastic pollution (UNEP 2021a). Plastic pollution entering the ocean is expected to triple by 2040 to 29 million metric tons per year, and the total plastic stock in the ocean will quadruple to 646 million metric tons by 2040 without significant action (Lau et al. 2020). The presence of plastics in the ocean threatens all marine life through entanglement and ingestion, habitat disturbance, and chemical uptake (Gall and Thompson 2015; UNEP 2021a). Microplastics in the ocean can act as vectors for pathogenic organisms and alter the reproduction rates and life expectancy of marine species (UNEP 2021a). There is also growing evidence that exposure to the chemicals in plastics can lead to chronic health conditions, including cancers, diabetes, obesity, and infertility, whereas microplastics and nanoplastics could have additional toxic effects because of their ability to cross biological membranes, including the brain and placenta (Bidashimwa et al. 2023). Given their proximity and exposure to plastic pollution, workers in the blue economy are likely to be particularly vulnerable to plastic-related health concerns.

The World Bank was an early actor in tackling marine plastic pollution largely because of the support of the PROBLUE trust fund. Although the World Bank has addressed marine plastic pollution through its investments in solid waste management for at least two decades, the World Bank’s specific focus on plastic pollution can be traced to the establishment of a dedicated funding window (in 2018), within the PROBLUE multidonor trust fund. PROBLUE has provided 68 grants for $45 million in support of 39 pieces of analytic work and co-financing for 29 investment operations (representing 35 percent of PROBLUE’s total budget). The World Bank also has provided policy support to address plastic waste (12 development policy loans).

The World Bank’s global plastics analytics and estimation models are being used by policy makers to tackle plastic pollution. World Bank global analytics include the flagship report Where Is the Value in the Chain? Pathways out of Plastic Pollution (2022k), which brings insights from the development of two models: the Plastics Policy Simulator and the Plastic Substitution Tradeoff Estimator. The Plastics Policy Simulator is a capacity development model for policy makers to estimate how businesses and households will react to implementing new plastics policies and the costs, revenues, and other impacts of those policies. The Plastic Substitution Tradeoff Estimator assesses the costs and benefits of alternative materials in monetary, quantitative, and qualitative terms in 10 single-use plastic products, including bottles, cutlery, food wrapping, and diapers. These models are filling an important gap because very few similar open-access tools exist for national-level exploration of plastics policy options and show positive signs of early uptake. We found that the Plastics Policy Simulator and the Plastic Substitution Tradeoff Estimator are being applied, for example, in countries such as the Philippines, which is one of the highest plastic waste polluters in the world, as shown in figure 3.1, and by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Regional Action Plan for Combating Marine Debris, which has been endorsed by 10 countries, including many high-polluting countries.5 The tools are also being applied in Georgia, Türkiye, and Ukraine as part of the Europe and Central Asia Regional program Blueing the Black Sea. Other tools developed by the World Bank, such as waste audits, were applied in Kiribati, Samoa, and Tonga in the Pacific Islands. The World Bank has also significantly contributed to shaping the national plastics road maps of Ghana, Indonesia, Lebanon, Morocco, Pakistan, Tunisia, and Viet Nam through its partnership with the World Economic Forum’s Global Plastic Action Partnership. The Indonesia and Pakistan action plans, for example, use the World Bank’s What a Waste database and, together with Ghana’s road map, use its plastic hierarchy theory to outline the systematic changes needed for effective plastic waste management.

Figure 3.1. Highest Ocean Plastic Waste Polluters

Source: Lugas Wicaksono 2023, ©Visual Capitalist. Reproduced with permission, from Visual Capitalist; further permission required for reuse.

Note: Annual estimation is in metric tons.

The World Bank has provided important development policy support to address marine plastic issues in SIDS but not in the coastal nations that rank as major contributors to plastic waste production. The World Bank has concentrated its policy support on addressing plastic waste in or affecting the marine space through development policy financing, with 58 percent (7 out of 12) of prior actions targeting SIDS, which are not the principal generators of plastic waste.6 Although this is suboptimal from a global perspective, these interventions are yielding considerable environmental advantages locally. For example, the Grenada Fiscal Resilience and Blue Growth development policy credits had prior actions to ban Styrofoam food containers, single-use plastic bags, and disposable plastic cutlery, which resulted in an almost complete import ban of such products. Similarly, prior actions for the St. Vincent and the Grenadines Second Fiscal Reform and Resilience development policy credit supported the phaseout of the import, distribution, and use of single-use plastic bags and plastic food containers to reduce waste generation and marine pollution. Prior actions included in the Solomon Islands Transition to Sustainable Growth development policy operation series helped introduce an environmental levy on single-use plastics and other plastics with toxic components to reduce plastic pollution. However, there is a notable absence of policy operational support in many coastal nations shown in figure 3.1 that rank as major contributors to plastic waste production. Notable policy actions in the Philippines, the highest-polluting country, include the enactment of the Extended Producer Responsibility Act requiring large enterprises to recover up to 80 percent of plastic packaging waste by 2028. Otherwise, development policy operations have supported a tax on plastic bags in Colombia and a ban on the use of single-use plastic bags beneath a certain thickness in Albania, neither of which is a top polluter. This discrepancy suggests a potential misalignment between the geographical focus of policy support and the areas where it could achieve the most impact on global plastic waste reduction.

The World Bank has also not clarified the connection between its commitments to achieve a just climate change transition to its circular economy (plastics and pollution) agenda. A key area of debate in the ongoing Global Plastics Treaty negotiations is how the necessary circularity shift in the global plastics economy might affect vulnerable communities, with many countries and groups insisting that a just transition is essential to effectively tackle plastic pollution in a way that is acceptable to all parties. In alignment with this position, the World Bank has indicated that the solutions to plastic pollution should not “penalize poor countries, or poor communities in every country” and that “we must design solutions with the needs and realities of the poorest communities in mind, to ensure a ‘just transition’” (Hickey 2023). However, this position is not clearly reflected in some of the World Bank’s key guidance on tackling plastic pollution. For example, neither Where Is the Value in the Chain? Pathways out of Plastic Pollution (World Bank 2022k) nor Tackling Plastics Pollution: Towards Experience-Based Policy Guidance (World Bank 2022i) advocate a just transition or specifically mention the term. Although these reports, and the associated tools,7 acknowledge social dimensions and the need for integrating social considerations into policy reforms, the broader concept or contemporary understanding of a just transition, as highlighted by stakeholders in the Global Plastics Treaty negotiations,8 is not captured, and the tools do not clarify specific measures. Similarly, the recently published Plastic-Free Coastlines: A Contribution from the Maghreb to Address Marine Plastic Pollution (World Bank 2022f) does not mention a just transition. Given the World Bank’s view that tackling plastic pollution is key to its fight to tackle poverty and its commitment to supporting the blue economy, there is room for further alignment with this key consideration in the Global Plastics Treaty negotiations.

Marine and Coastal Tourism

Tourism, a key sector of the blue economy, offers significant opportunities for employment, income, and foreign exchange in developing countries, but it requires careful balancing of environmental and sociocultural impacts within a blue economy transition. Making up about 50 percent of global tourism, marine and coastal tourism generate $4.6 trillion annually, accounting for 5.2 percent of global GDP (Northrop et al. 2022). It is an essential part of the economy for small islands and coastal communities. Although COVID-19 severely affected the sector and those dependent on it, international tourism flows recovered to almost 60 percent of prepandemic levels by July 2022 (OECD 2022). Amid this recovery, tourism’s potential benefits are contingent on sustainable management because unmanaged tourism exerts pressures on limited marine and coastal resources, leading to environmental, economic, and social harm. Environmental impacts include pollution (including plastics),9 habitat and reef destruction for infrastructure development,10 biodiversity loss, shoreline erosion, water resource depletion, and increased greenhouse gas emissions. Climate change exacerbates these pressures as rising sea levels and increased storm frequency threaten both natural ecosystems and the tourism infrastructure dependent on them. Unsustainable tourism can also erode traditional culture and local economies. It can lead to overdependence on tourism, increase crime and conflicts, and crowd out traditional businesses (Lei, Suntikul, and Chen 2023). Transitioning the marine and coastal tourism sector within a blue economy calls for an approach that (i) is informed by an integrated planning framework such as MSP to designate tourism locations appropriately and balance trade-offs between tourism and other sectors; (ii) prioritizes and supports ecosystem health and resilience; and (iii) ensures comprehensive stakeholder engagement, with particular attention to the needs of marginalized groups (Hickey 2022). Tourism engagements that adopt a blue economy approach can help mobilize financing, knowledge, and technical assistance to implement integrated development strategies that build resilience, address climate change, reduce pollution, support ecosystem regeneration and biodiversity conservation, and invest in local jobs and communities (Northrop et al. 2022).

The World Bank’s core coastal and marine tourism portfolio has contributed to local economic development and jobs, with some evidence of success, but it has paid insufficient attention to upstream environmental issues, including water use and waste. Since 2016, the World Bank has financed 17 analytic products and 14 lending projects focused on tourism development (all were developed by the Finance, Competitiveness, and Innovation GP), which is the subject of this assessment.11 ,12 Of the 14 lending operations approved since the launch of the blue economy agenda in the World Bank (2016 onward) that have supported coastal and marine tourism, 6 have passed the Mid-Term Review stage and 3 are closed; most (78 percent) are in Africa. In this cohort of mature or closed projects, most contributed to increased private investment in tourism destinations by supporting tourism promotion and marketing plans and by improving infrastructure. They also supported diversification aims by connecting micro, small, and medium enterprises to tourism markets through training and certification, which also enabled some of these micro, small, and medium enterprises to access finance. Notwithstanding these economic achievements, none of these projects worked upstream to reduce the production of waste or pollution, or excess use of water, that would result from the envisioned increase in tourism, and only 2 projects included and tracked tourism-related waste management activities (in Indonesia and Senegal).

As of 2022, the World Bank put forth a blue tourism paper that represents a shift away from its prior tourism theory of change and that is capable of supporting blue economy aims. Blue Tourism in Islands and Small Tourism-Dependent Coastal States: Tools & Recovery Strategies (World Bank 2022a), financed by PROBLUE, represents a strong departure from the World Bank’s prior tourism theory of change, published in 2018, which focused mostly on competitiveness and diversification (World Bank 2018d). That theory of change report did not reference the blue economy, oceans, pollution, waste management, or plastics. The concept of environmental sustainability is also not clearly integrated within the guidance. Most of the coastal and marine tourism portfolio, approved since 2016, focused on market development and investment promotion; micro, small, and medium enterprise integration, which enables infrastructure and services; and to a certain extent, more recently, economic diversification. Conversely, the World Bank’s new tourism paper explains how countries and operations can shift to a more sustainable and resilient (financially, environmentally, socioeconomically, and culturally) tourism approach. The shift was stimulated by the sector crises caused by COVID-19, which prompted many governments and the World Bank to rethink the way they are engaging in the sector. The transition envisioned is one that moves the tourism sector away from high-impact, environmentally and culturally damaging activities toward low-impact, high-value tourism growth that proactively supports local communities and the conservation of natural resources. Importantly, the guidance also emphasizes the need for cross-sector coordination, which is critical for achieving blue economy aims: “tourism needs to be considered not as a discrete area but in connection with sustainable fisheries, agribusiness, transport, and rural development” (World Bank 2022a, 12). There is evidence that these principles have been taken up in one new tourism promotion project—the Resilient Tourism and Blue Economy Development in Cabo Verde Project (2022–present)—which promotes and tracks the number of beneficiary small and medium enterprises that take up environmentally friendly practices (for example, water conservation, waste management, and reduction of greenhouse gas emissions). Time will tell whether other tourism operations will follow suit now that they are supported by PROBLUE.

Maritime Transport Infrastructure

Maritime transport is an integral part of a holistic blue economy system, but maritime policies and infrastructure have historically been developed in silos. Maritime policies that concern the securitization of water rights, shipping, and navigational issues, as well as port design and expansion, have often been developed in isolation from other sectors. Decisions about the placement and development of fisheries ports and container or cruise terminals have been left to the markets without being integrated into marine and land use planning processes that consider their environmental and social effects. The industry has relied on heavy and intermediate fuel oils that pollute the sea and air and are a major source of greenhouse gas emissions (Helton 2023). Maritime transport contributes to approximately 30 percent of global nitrogen oxide emissions and 2.9 percent of total greenhouse gas emissions (OECD 2024). Solid waste has also been dumped into the ocean, winding up on coastlines and carried with the current to distant shores, rather than being managed responsibly.13 Ports range from deepwater container terminals that often are not socially inclusive to fishing ports and docks where there are ample opportunities to support local jobs and provide access to local markets with appropriate upstream planning and community engagement.

Aspects of the blue economy in the marine transport space—such as decarbonization and greening of ports—have been covered by World Bank analytics, but operational uptake is low. With the support of PROBLUE, the World Bank has developed analytics on the decarbonization of shipping and the greening of ports. Since the introduction of the Blue Economy Development Framework in fiscal year 2016, the World Bank has approved 14 investment projects that support maritime transport, seaports, or inland waterways connected to the coast. Among them, 5 projects in the Comoros, Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and Tonga have interventions designed to enhance the disaster resilience of their seaports, mainly through gray infrastructure.14 Only two maritime transport projects, in the Comoros and Kiribati, assess and address trade-offs as part of an MSP approach (financial, environmental, and social) using a blue economy lens (box 3.2). World Bank analytics are also yielding insights into the financial dimensions of decarbonizing maritime transport, particularly in carbon revenue allocation, and this knowledge has been shared globally at the 27th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Two South Asian maritime transport projects (approved in fiscal years 2016 and 2017) support decarbonization of maritime shipping through cleaner fuel adoption (however, both projects were undergoing restructuring at the time of the evaluation, so results could not be reported). However, other maritime transport projects in coastal states that focus on operational safety, physical expansions, and administrative management do not include references to environmental or social considerations beyond safeguards or the wider blue economy (including in Colombia, Côte d’Ivoire, Indonesia, Somalia, Tanzania, and Togo). There are also opportunities to partner or engage in mutual learning in this space, for example, with the African Union, which has placed sustainable port development at the center of its blue economy strategy with support from the African Development Bank (AfDB 2022).

Box 3.2. Maritime Transport Projects That Use a Blue Economy Lens

Two recently approved projects in Kiribati and the Comoros stand out for their integration of environmental and social considerations into maritime transport. The Kiribati Outer Islands Transport Infrastructure Investment Project (P165838), approved in fiscal year 2020, has technical assistance to enhance the government’s capacity in using marine spatial data. This is expected to enable the monitoring of cargo shipping activities’ impact on lagoon marine resources and reefs while facilitating climate-informed maritime operations. Similarly, the Comoros Interisland Connectivity Project (P173114), approved in fiscal year 2022, incorporates considerations for coastal communities’ social welfare in its project design. The seaports are designed to accommodate fishing boats and other small cargo vessels, allowing local fishing communities to develop their business in the port areas and thus promoting coexistence between local fishery and maritime transport industries.

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group; World Bank 2020a, 2022c.

Blue Economy at the Corporate Level

The PROBLUE trust fund has been instrumental in helping the World Bank finance blue economy analyses, lodged within advisory services and operations. PROBLUE is a multidonor trust fund established in 2018 and administered by the World Bank’s ENB GP. Donors include Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Norway, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States. It has supported over 180 grants in 80 client countries, with a total contribution of over $220 million, that have supported 84 ASAs and 46 lending operations (of which all but 2 are active and in the pipeline). PROBLUE finances four eligible pillars of work: (i) fisheries and aquaculture management; (ii) marine pollution, including litter and plastics; (iii) oceanic sectors (“blueing” sectors, such as tourism, maritime transport, offshore renewable energy, desalination, and so on); and (iv) seascape management (building government capacity for integrated marine resource management). As noted in the Articulation of the Blue Economy in Country Diagnostics section in chapter 2, focused blue economy analytics have been critical for articulating the blue economy in country diagnostics. Although PROBLUE had predominantly supported blue economy analytics housed in the ENB GP during its early years (100 percent of grants were provided to ENB GP as of 2019), it has also supported blue economy analyses in other sectors between 2019 and 2023 (one-fifth of the PROBLUE grants were provided to other sectors for ASA in 2023).

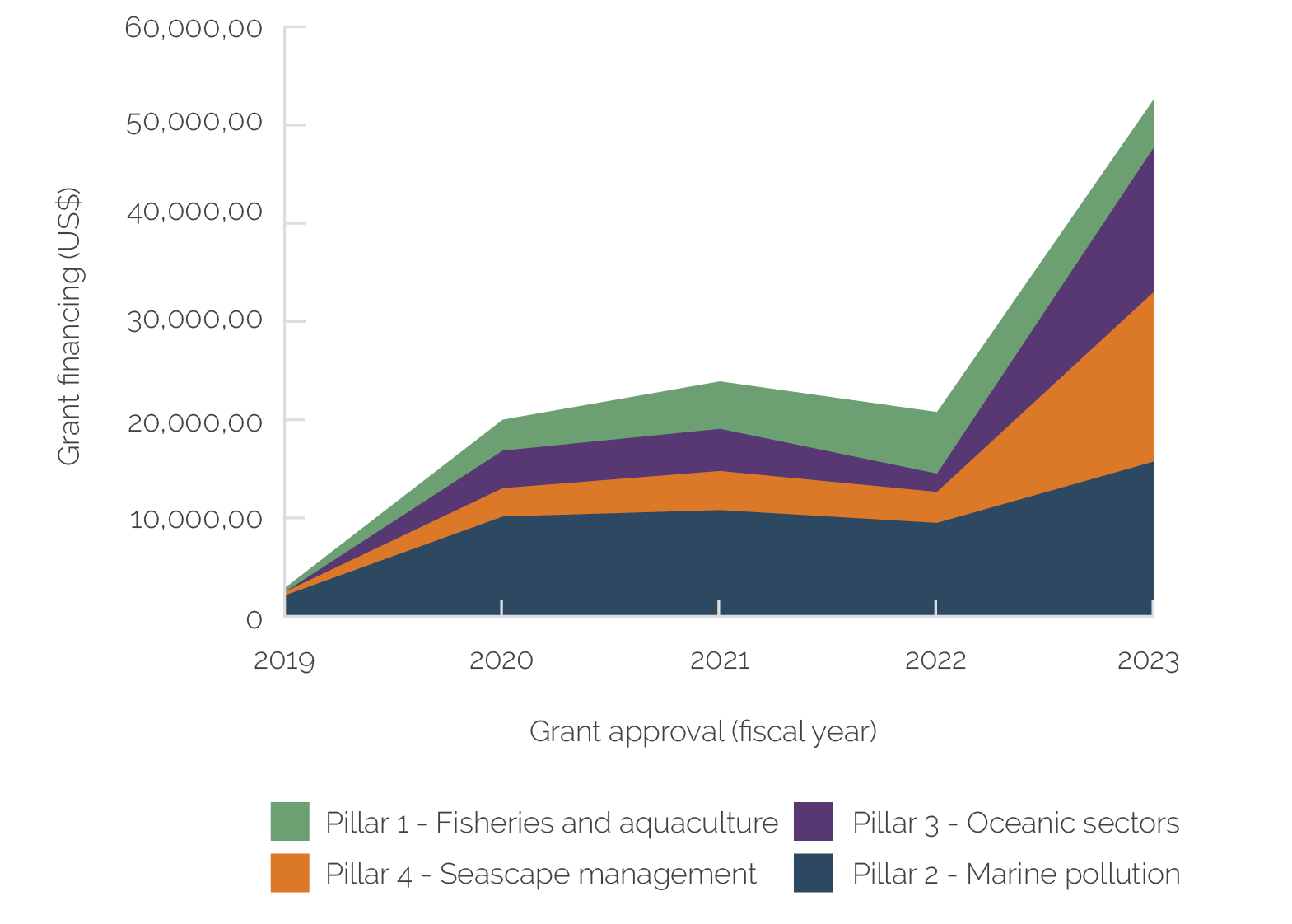

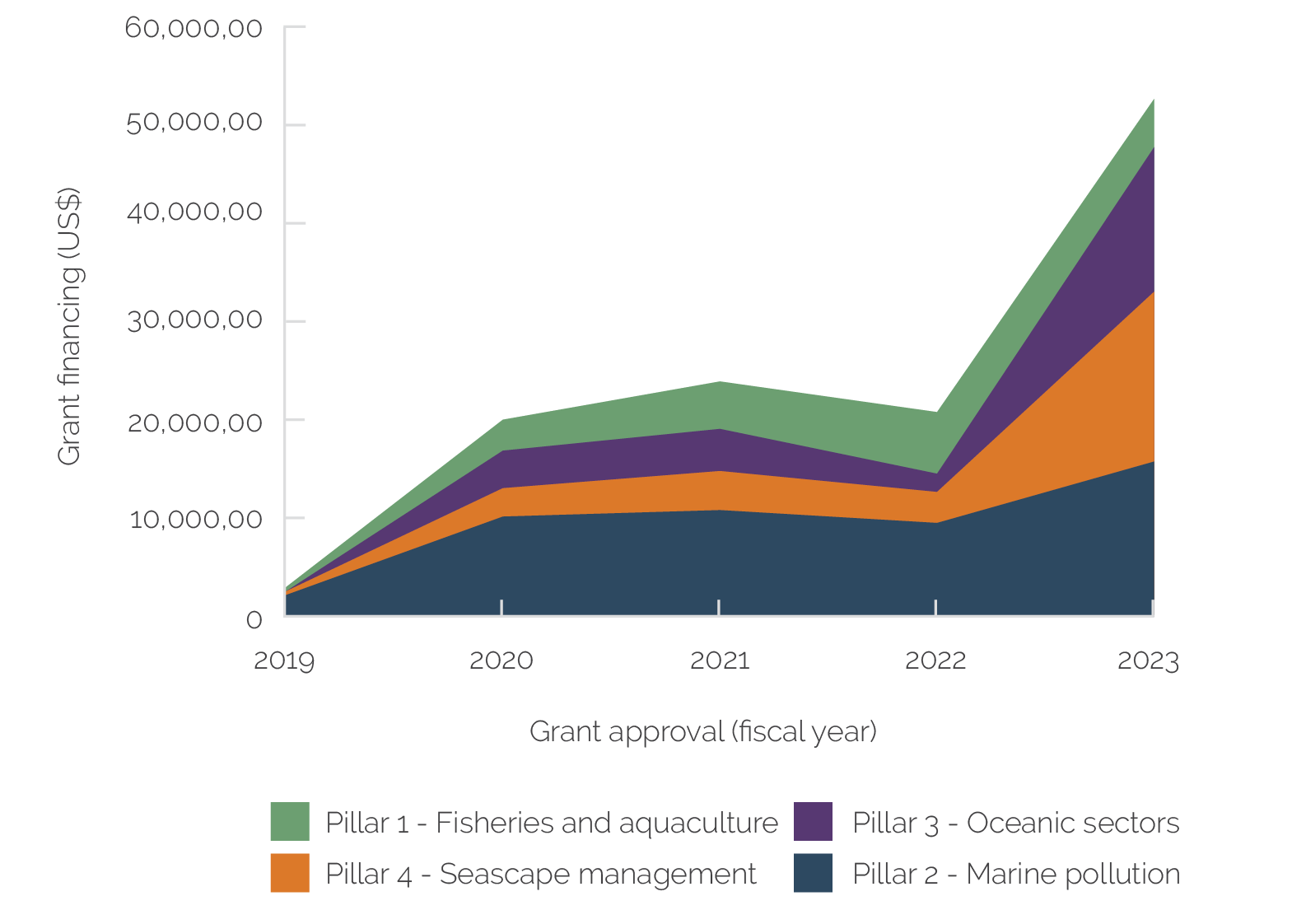

PROBLUE’s support has had a pronounced focus on marine pollution, but recent trends show increased pillar diversification in line with wider blue economy aims. Since its inception, PROBLUE has demonstrated a strong commitment to tackling marine pollution by directing 40 percent of its total grant financing toward pillar 2. The share of annual funding dedicated to pillar 2 started at a peak of 73 percent in 2019 and decreased to 30 percent by 2023, although in absolute terms, the share has increased in line with PROBLUE’s tripling of grant approvals during this period (see figure 3.2). By 2023, PROBLUE’s financing had shown a significant increase in diversification, especially in financing seascape management (pillar 4) and oceanic sectors (pillar 3), which are most in line with wider blue economy aims. Fisheries and aquaculture remain the least funded pillar, having received only 16 percent of PROBLUE’s financing over its lifetime.

Figure 3.2. PROBLUE Financing by Pillar, by Grant Volume

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

PROBLUE funds have only infrequently been used to help integrate blue economy principles into investment operations in other key sectors. Two-thirds of PROBLUE grants provided to lending operations have been used by ENB to enhance the sustainability of small-scale fishing, capacity building for solid waste management, and piloting nature-based tourism—activities in line with blue economy aims. However, PROBLUE grants have only infrequently been used to promote the adoption of a blue economy approach within other GPs, which would entail the provision of PROBLUE finance for engagement of ENB staff in sector operations in key blue economy areas, such as tourism or marine transport. Good examples include co–task team leadership of the Mozambique Sustainable Rural Economy Program and the Resilient Tourism and Blue Economy Development in Cabo Verde Project and ENB cross-support to the Jamaica Disaster Vulnerability Reduction Project.

PROBLUE is supporting gender integration through analytics and criteria in their grant proposals, but it is too soon to assess gender outcomes in projects, although enhanced monitoring and reporting are needed at the project and portfolio levels. PROBLUE has demonstrated a strategic commitment to gender integration by incorporating gender criteria in its grant proposals and by producing key analytics.15 For example, by June 2023, 93 percent of all PROBLUE grant recipients had articulated how gender results would be achieved in their respective operations. Since projects have not sufficiently captured and reported on gender-disaggregated effects, however, plans are underway to use more specialists on gender and gender-based violence in PROBLUE-financed operations.

- Although the Eastern Caribbean states had indigenously put forth the St. George’s Declaration of Principles for Environmental Sustainability in the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS)—the existing vision of the blue economy in the OECS—support was needed to translate that vision into regional and national policy, produce national asset accounts, and harmonize and update sector legislation. The St. George’s Declaration of Principles for Environmental Sustainability in the OECS (signed in 1999, ratified in 2001, and revised in 2006) is the benchmark environmental management framework in the Eastern Caribbean region. The declaration is structured around 21 principles to guide sustainable development, mandating their delivery by OECS member states, and sets out clear requirements for monitoring environmental impacts and trends in ecosystem health.

- This has included accounting exercises to provide initial measures of ocean-linked economic activity, undertaking Public Expenditure Reviews for the blue economy; guidance, action plans, and road maps to introduce blue economy tools such as marine spatial planning; and analyses for key sectors considered important for blue economy development.

- The Arab Republic of Egypt—Alexandria Coastal Zone Management Project (fiscal year [FY]10; P095925): The population is already benefiting from having a coordination mechanism in place through the adoption of the integrated coastal zone management plan, which will allow the regular monitoring of water quality and biodiversity along the coast. Beneficiaries were consulted, and they participated in the development of the plan. Pollution reduction will allow fishers to catch less contaminated and better-quality fish (Mugil cephalus instead of less valuable fish, such as tilapia), including the restoration of wetland and biodiversity conservation. Stakeholders have also benefited from integrated coastal zone management training, which has helped with sustainably managing the future land use of the city, potentially increasing coastal fishing and recreational activities. The Namibian Coast Conservation and Management Project (FY06; P070885): The proclamation of the Sperrgebiet National Park (now called Tsau/Khaeb) in 2008, the Namibian Islands Marine Protected Area in 2009, and the Dorob National Park in 2010, linking the Namib-Naukluft Park and the Skeleton Coast National Park in 2011, contributed to the achievement of the project development objective. India—Integrated Coastal Zone Management Project (FY10; P097985): Achievements included delineation of 7,500 kilometers of coastal hazard line for India and restoration of over 16,000 hectares of mangroves and 2,000 hectares of shelterbelt. Innovative environmental infrastructure includes sewage treatment plants in Gujarat with private sector participation and island electrification in West Bengal. Livelihood improvements and environmental services directly benefited 1.84 million people and indirectly 13.8 million people (over 50 percent women). Morocco—Integrated Coastal Zone Management Project (FY13; P121271): The project included the restoration of 500 hectares of degraded land, which reduced erosion and created jobs and income benefits. Albania—Integrated Coastal Zone Management and Clean-up Project (FY05–15; P086807): The project dropped its objective to enhance regulatory policy and governance of the coastal zone, land use and regional planning, and institutional capacity. However, it assisted the government of Albania with improving critical infrastructure and municipal services along its southern coast. This included the construction of a sanitary landfill that can accommodate the disposal of 25,000 tons of waste annually, construction of a 180-meter new berth front with 9-meter water depth, remediation of contaminated sites from a former chemical plant, water supply and sewerage infrastructure, and road improvements. West Africa Coastal Areas Resilience Investment Project (FY18, P162337): Achievements included 4,028 households in targeted coastal areas with less exposure to erosion, 14,368 households in targeted coastal areas with less exposure to flooding, 1,250 households in targeted coastal areas with less exposure to pollution, 168.75 hectares of targeted coastal area with flooding control measures, 6.79 kilometers of shoreline with targeted coastal erosion control measures, two sites or zones with pollution control measures, and 4,491 coastal households with access to improved livelihood activities.

- From Independent Evaluation Group discussions held with the African Union Interafrican Bureau for Animal Resources and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development in August 2023.

- Further alignment and implementation support of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Regional Action Plan provided as part of country-level investment project financing work—for example, the PROBLUE-supported investment project financing to Cambodia (P170976).

- The development policy operations have been led by the Macroeconomics, Trade, and Investment Global Practice (n = 9); Environment, Natural Resources, and Blue Economy (n = 2); Social Protection and Jobs (n = 1); and Urban, Disaster Risk Management, Resilience, and Land (n = 1).

- Namely, the Plastics Policy Simulator and the Plastic Substitution Tradeoff Estimator tools.

- For example, the Scientists’ Coalition for an Effective Plastics Treaty, in a briefing note for treaty negotiators published in 2023 titled Towards a Just Transition Away from Plastic Pollution, states that “provisions for a just transition away from plastic pollution have been viewed as necessary in the ongoing negotiations towards an international legally binding instrument to end plastic pollution (henceforth, plastics treaty). In this context, just transition means ensuring that measures taken to end plastic pollution are fair, equitable[,] and inclusive for all stakeholders across the plastics life cycle by safeguarding livelihoods and communities impacted by plastic pollution and corresponding control measures. A just transition entails recognizing the inequitably distributed impacts of plastic pollution across the plastics life cycle, ensuring decent and green work opportunities and conditions for affected communities and workers across the plastics value chain, reducing inequalities, particularly among women and youth, and leaving no-one behind in the transition towards ending plastic pollution” (O’Hare et al. 2023).

- Tourism can exacerbate marine litter, solid waste, and wastewater problems, particularly when infrastructure to accommodate increased visitors is insufficient. For example, the volume of marine litter in the Mediterranean region increases up to 40 percent during the peak tourist season, causing environmental damage and deterring tourists from visiting (WWF 2019). A recent PROBLUE study found that marine plastic pollution resulted in a measurable economic cost to tourism of approximately $18 million in Tanzania and Zanzibar (McIlgorm and Xie 2023). Discharge from boats and cruise ships and chemical sunscreen also negatively affect water quality and marine ecosystems.

- Tourism infrastructure development, including hotels and roads, often leads to environmental degradation, destroying vital coastal ecosystems, such as mangroves and seagrass, through land and beach clearing. In 2010, the state of Quintana Roo in Mexico, where Cancún is, was losing approximately 150,000 hectares of mangroves per year as a result of land clearing for hotels and resorts (Vidal 2010).

- Since 2016, the Finance, Competitiveness, and Innovation Global Practice has produced 17 advisory services and analytics, including six country analyses (Cabo Verde, Pakistan, Sint Maarten, Tanzania and Zanzibar, Timor-Leste, and Uruguay), two in the Caribbean (OECS), two in the Pacific region, one focused on the Indian Ocean subregion, and five global. It has also approved 14 lending projects (and four additional financing) that have a core focus on coastal and marine tourism across 12 countries—in Benin, The Gambia, Ghana, Indonesia, Madagascar, the Republic of Congo, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and four small island developing states (Cabo Verde, the Comoros, OECS, and Suriname).

- Other Global Practices have also supported projects with marine tourism activities (often lodged within components), including Urban, Disaster Risk Management, Resilience, and Land and Environment, Natural Resources, and Blue Economy, which are not the subject of this assessment.

- Maritime transport is the source of waste and pollution entering the seas and oceans in a direct way. The ports in the region lack waste reception facilities, and many ships dump their wastes at sea, and the waste is then transported to distant locations by winds and currents (UNEP 2021a).

- “Gray infrastructure is built structures and mechanical equipment, such as reservoirs, embankments, pipes, pumps, water treatment plants, and canals. These engineered solutions are embedded within watersheds or coastal ecosystems whose hydrological and environmental attributes profoundly affect the performance of the gray infrastructure” (Browder et al. 2019, 14).

- These include Gender Integration in the Blue Economy Portfolio: Review of Experiences and Future Opportunities (World Bank 2022d) and “Gender, Marginalized People and Marine Spatial Planning: Improve Livelihoods, Empower Marginalized Groups, Bridge the Inequality Gap” (World Bank 2021a).