Making Waves

Chapter 1 | Background and Context

Ocean and coastal resources are integral to sustaining life on Earth. Oceans cover 71 percent of our planet’s surface, contain 97 percent of its water, are home to over 90 percent of its species, and produce more than 60 percent of all oxygen (Cousteau, Cousteau, and Kraynak 2021). Oceans play a crucial role in climate regulation, absorbing 30 percent of carbon dioxide emissions and over 90 percent of the excess heat from global warming (IPCC 2019). Coastal resources are natural resources occurring within coastal waters and their adjacent shorelands that include salt marshes, wetlands, floodplains, estuaries, beaches, dunes, barrier islands, mangroves, and coral reefs, as well as fish and wildlife and their respective habitats. Coastal resources, such as mangroves, are vital for carbon sequestration—acre by acre, mangroves store up to four times more carbon than terrestrial forests (Donato et al. 2011). Moreover, coral reefs and mangroves act as natural buffers and mitigate coastal flooding; coral reefs can dissipate up to 97 percent of wave energy, and mangroves provide flood protection benefits of some $65 billion in annual avoided losses (Menéndez et al. 2020).

Oceans and coastal resources are vital for inclusive growth, jobs, and food and nutrition security. The value of marine and coastal resources and industries (for example, fishing, aquaculture, shipping, tourism, offshore energy) is estimated to be between 3 and 5 percent of global GDP (Patil et al. 2016). Tourism—80 percent of which involves coastal and marine activities—is a crucial source of jobs and livelihoods in developing countries, where most people who work in tourism reside (OECD 2020; WTTC 2022). Small-scale fisheries account for at least 40 percent of the world’s total fisheries catch, and approximately 500 million people depend on small-scale fisheries for their livelihoods, mainly in developing countries (FAO, Duke University, and WorldFish 2023). In the least-developed countries, seafood is the primary protein source for over 50 percent of people, and fishing is used as a social safety net for people living in poverty (FAO 2022). For small island developing states (SIDS),1 the exclusive economic zone—the ocean under their control—is, on average, 28 times the country’s land mass. Thus, the economies of many SIDS are largely dependent on ocean and coastal resources that also sustain livelihoods and employment.

Ocean and coastal resources are in a state of emergency as a result of governance and management failures compounded by low institutional capacity. Oceans and coastal areas have been treated as limitless resources and largely cost-free repositories of waste (World Bank and UN DESA 2017). The policies governing ocean and coastal resources are often fragmented, characterized by legal and regulatory gaps and overlapping institutional mandates. There are limited incentives for institutions to coordinate rather than compete. Institutions also often exhibit information and skill gaps, such as in natural capital accounting and ocean and coastal spatial planning, which undermine their ability to effectively govern. Ill-regulated coastal development has resulted in the destruction of 1 million hectares of mangroves between 1990 and 2020 (FAO 2020a; Merzdorf 2020). Some 34 percent of global fish stocks have been overfished, including as a result of illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing (FAO 2020b). Oceans and marine life are also at risk from perverse policies that have failed to prevent 11 million tons of plastic waste and harmful chemicals from agricultural runoff, industrial processes, and wastewater from entering oceans annually (UNEP 2018). In addition, the lack of regulation does not bode well for the sustainable growth of established and emerging ocean and coastal sectors that are competing for limited space and resources.

Delayed climate action is further threatening oceans and coastal resources, resulting in a cascade of negative environmental and human welfare effects. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has pointed to the unprecedented and enduring threats to the ocean from climate change, including the escalating costs and risks of delayed action. The projected global rise in sea levels and temperatures threatens to destroy valuable ocean and coastal resources critical for livelihoods and human well-being. Sea level rise is displacing hundreds of millions of people living in coastal areas (Kulp and Strauss 2019). Changes in ocean currents and temperatures are altering fish migration patterns, affecting yields and community welfare. For example, a 1°C increase in sea surface temperature is expected to reduce global fishery yields by 4 percent, or 3.4 million tons (IPCC 2019). Coral bleaching and mortality events, caused mainly by rising sea temperatures, can lead to a significant loss of local revenue from reduced tourist activity and access to the fish that feed off coral reefs. Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia, and the Maldives derive almost 60 percent of their tourism income from their coral reefs (UN-OHRLLS 2021).

International actors have progressively proposed using a blue economy approach to address ocean and coastal governance failures. The notion of the blue economy was introduced at the 2012 Rio+20: The United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development by coastal countries that noted that even though many understand how to stimulate economic growth in ocean areas, there has been a lack of focus on the policies, conditions, and pathways needed to achieve sustainable and inclusive ocean and coastal economies. Although there is no single definition of the blue economy, international actors have coalesced around the need to achieve a triple bottom line—that is, the need to achieve healthy ocean and coastal resources that underpin inclusive and equitable economic growth and the achievement of social welfare benefits (including food and nutrition security). The blue economy implies a shift from sector-led to integrated approaches requiring sector coordination to identify potential synergies and to manage trade-offs among different resource user groups and development aims. Although important sector outcomes have been achieved, these outcomes have been undermined by externalities from other sectors. For example, efforts to restore mangroves or support fishers have been undermined by ill-sited ports and unregulated tourism. Governments and the private sector have also missed opportunities to invest in ecosystem services to increase profits from seafood harvests and enhance food and nutrition security. In addition, international actors point to a sense of urgency because of the expansion of existing and emerging ocean industries (for example, offshore renewable energy and deep-sea mining) that, together with the negative effects posed by climate change, are threatening the life-sustaining services provided by ocean and coastal resources. The blue economy is also seen as a way to support wider climate change, biodiversity, and circular economy aims.

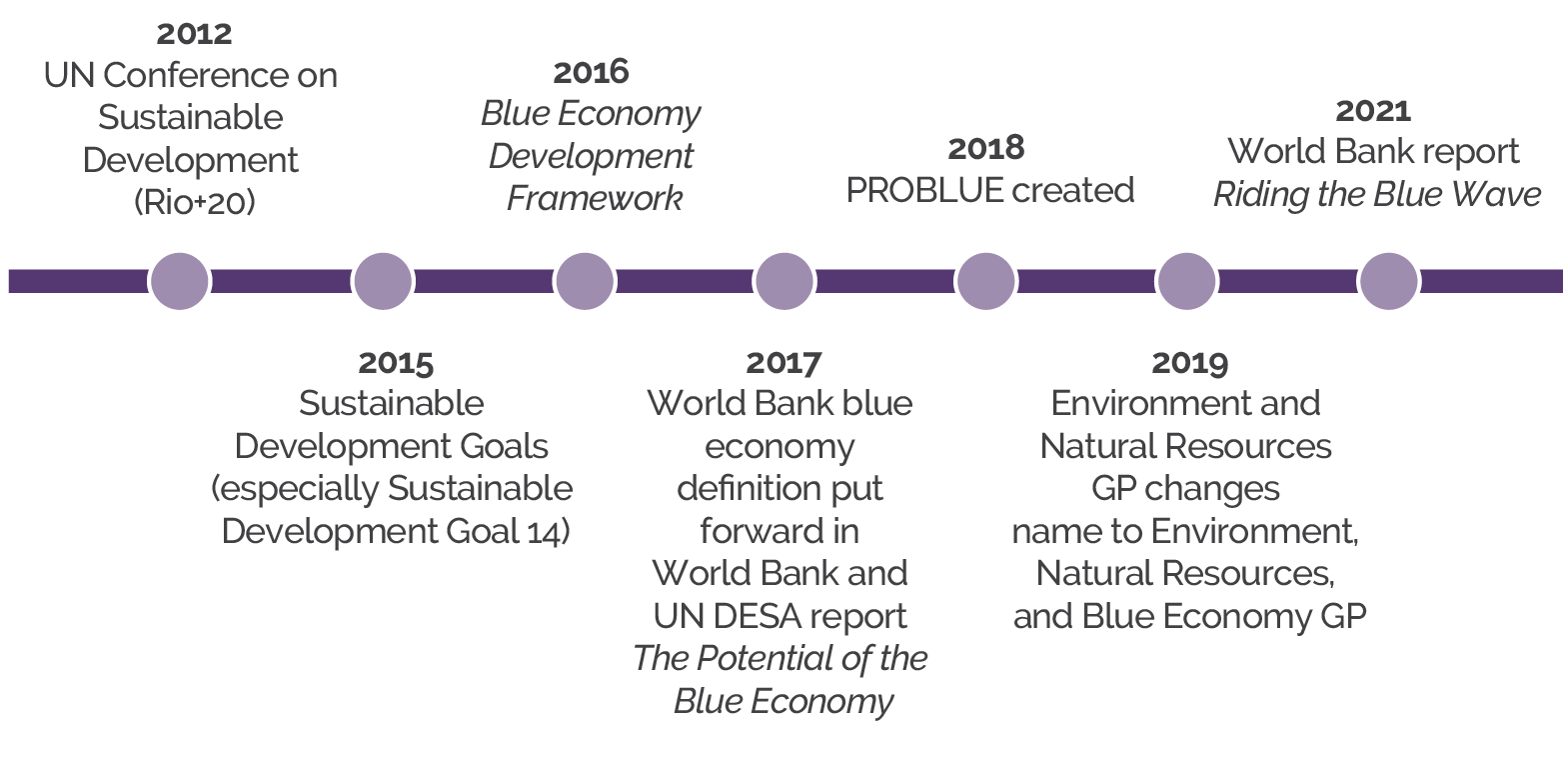

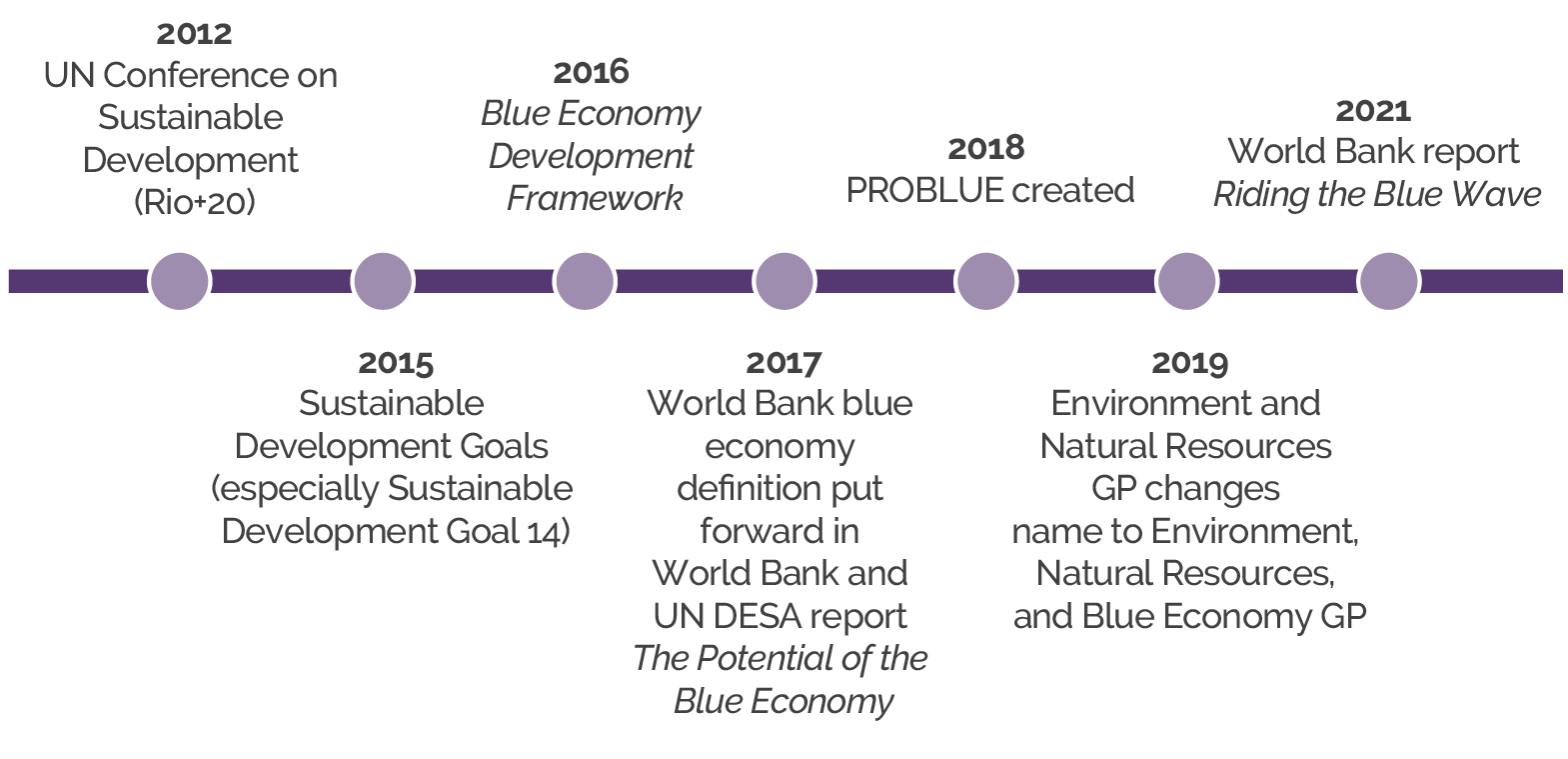

The World Bank adopted a blue economy approach in 2016. Although the World Bank has engaged for decades in marine and coastal development,2 it put forth a blue economy definition and an initial blue economy framework between 2016 and 2017. The World Bank’s 2017 definition of the blue economy is the “sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and job creation while preserving the health of ocean ecosystems” (World Bank 2017e). Pursuant to this definition, the World Bank published a series of blue economy analytics at the global, regional, and country levels; became home to a multidonor PROBLUE trust fund that supports the blue economy; and, in 2019, changed the name of its Environment and Natural Resources Global Practice (GP) to Environment, Natural Resources, and Blue Economy (ENB). The World Bank’s support for the blue economy aligns with its support to clients to achieve the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals, especially Sustainable Development Goal 14 (Life below Water), and climate change aims (figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Timeline of World Bank Engagement in the Blue Economy

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: GP = Global Practice; UN = United Nations; UN DESA = United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

Evaluation Purpose, Questions, Scope, and Methods

The evaluation purpose is to assess how well the World Bank is supporting a blue economy approach to achieve sustainable and inclusive development of ocean and coastal economies. The overarching evaluation question is, How well is the World Bank supporting a blue economy approach to achieve sustainable and inclusive development of ocean and coastal states? The two subquestions are (i) How well is the World Bank articulating blue economy aims, including in relation to other actors? and (ii) How well is the World Bank operationalizing blue economy aims? This evaluation was requested by the Board of Executive Directors’ Committee on Development Effectiveness and by World Bank management. Noting that the blue economy is an evolving approach, the World Bank explicitly requested a forward-looking evaluation—that is, an evaluation that aims to help surface early implementation lessons to inform the future development of the World Bank’s blue economy approach.

The evaluation scope consists of three parameters: geographic considerations, types of activities, and timing. The evaluation scope covers 109 countries with a coastline or any form of ocean access, including activities in their exclusive economic zone (within 200 nautical miles of their shoreline) but not activities in international waters where the World Bank has had any analytic or lending activities (see appendix B for the country list). These 109 countries include 32 SIDS and 77 coastal countries. For these countries, we cover all Systematic Country Diagnostics (SCDs; n = 84), Country Economic Memorandums (CEMs; n = 46), and Country Climate and Development Reports (CCDRs; n = 23). We also cover all World Bank–published focused blue economy analytics at the global, regional, and country levels (n = 38). The evaluation scope also includes four established sectors critical for the blue economy: (i) small-scale fisheries, (ii) plastics and marine pollution, (iii) marine and coastal tourism, and (iv) maritime transport infrastructure. For these sectors, we cover all World Bank advisory services and analytics (ASA) and lending approved between 2016 and 2023. The evaluation covers 2012–23 but mainly focuses on 2016–23, after the World Bank’s adoption of a blue economy approach. This is a World Bank–only evaluation (it excludes the International Finance Corporation and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency).

The evaluation used a triangulated set of methods to answer the evaluation questions. To assess how well the World Bank has articulated the blue economy, in relation to other actors, the evaluation undertook a focused literature review, conducted content analysis of World Bank blue economy–focused analytics and key partner publications, convened and conducted global expert interviews, and used content analysis to assess the presence and level of integration of the blue economy concept in World Bank country diagnostics (SCDs, CEMs, and CCDRs) for countries in scope. Structured templates and scoring rubrics were then used to quantify and conduct comparative analyses of these diagnostics. To assess how well the World Bank is operationalizing the blue economy at the country and regional levels, we conducted case studies in 9 out of 19 countries that have (i) an ongoing national blue economy process (strategy, policy, or institutional development) and (ii) World Bank operational support focused on the blue economy that was mature enough to evaluate. The nine cases are Bangladesh, Belize, Cabo Verde, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Morocco, the Seychelles, and St. Lucia (Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States [OECS]); an expanded validation review was also conducted for the Pacific Islands. To assess how well the World Bank is operationalizing the blue economy at the sector level, we used portfolio review and analyses and key informant interviews. We also examined the role of the PROBLUE multidonor trust fund—the fund established in the World Bank to support the blue economy—as part of the sector analyses. The methods are fully explained in appendix A.

- In recent years, the language of the “large ocean state” has increasingly been used by the leaders of various Pacific and Indian Ocean states as a counterpoint to the usual “small island developing state” nomenclature (Chan 2018). This emerging self-identification of large ocean states juxtaposes their small landmass and populations with the possession of sovereign authority over large swaths of the world’s oceans. Such authority is increasingly being exercised in the context of biodiversity conservation through expanding marine protected areas (an element of both the Sustainable Development Goals and the Aichi targets of the Convention on Biological Diversity). The term large ocean state has been deployed in the United Nations General Assembly debates (for example, by Anote Tong, former president of Kiribati) and as the theme of a regional meeting (at the 2012 Pacific Islands Forum summit, hosted by the Cook Islands, under the banner of “Large Ocean Island States: The Pacific Challenge”). In September 2016, when addressing the Annual Congress of the International Union for Conservation of Nature, Tommy E. Remengesau Jr., president of Palau, declared his country not to be a “small island state,” as might be the conventional description for a country of 25,000 people and a land area of only 500 square kilometers, but a large ocean state. The main justification for this was the establishment of the Palau National Marine Sanctuary, which designated 80 percent of Palau’s exclusive economic zone of 600,000 square kilometers as a “no-take zone” entirely closed to fishing activities—an area the size of California and the sixth-largest marine protected area in the world. The remaining 20 percent of Palau’s exclusive economic zone would be limited to domestic fishing only, barring foreign fleets in the service of marine protection and biodiversity conservation (Chan 2018).

- Since the launch of the blue agenda at Rio+20: The United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development in 2012, it became apparent that the sustainable development of ocean and coastal resources would require collaboration across nation states, sectors and industry areas, and public-private actors on a larger scale than previously achieved. At that conference, the World Bank launched the Global Partnership for Oceans and subsequently hosted the secretariat until 2015. The partnership focused on the sustainable economic development of ocean resources, including by supporting the implementation of projects designed to promote sustainable fishing, the protection of coastal and ocean habitats and biodiversity, and the reduction of marine pollution. Trust funds, such as the Global Program on Fisheries, known as PROFISH, helped enable the implementation of this portfolio.