World Bank Support to Jobs and Labor Market Reform through International Development Association Financing

Chapter 3 | Jobs Interventions

Highlights

The shift in the International Development Association (IDA) jobs strategy led to a change in the mix of jobs interventions in the portfolio. Focus on demand-side interventions increased, and, in line with the evidence literature, bundling of interventions is now common practice.

Overall, the choice and design of jobs interventions was well informed by evidence.

The prioritization of youth and women’s employment in the IDA jobs strategy also resulted in more focus on these two beneficiary groups in jobs interventions. However, despite a growing body of evidence from impact evaluations, interventions that specifically sought to improve women’s employment were infrequent in the portfolio, whereas youth employment projects were more common.

Overall, the performance of jobs interventions under implementation is on track. Two-thirds of jobs-related indicators in projects that have passed their Mid-Term Reviews were on track to meeting their targets. However, there were shortcomings in many of the underlying indicators.

Validated ratings for the limited number of closed projects supporting the jobs agenda were slightly better than those of the rest of the IDA portfolio. However, because of shortcomings in the underlying indicators, little is known about the effectiveness of the interventions, with IDA having fallen short of stimulating meaningful improvements in results measurement or in country-level statistical systems measuring labor market developments.

This chapter assesses the extent to which the shift in the IDA jobs strategy has influenced the portfolio of jobs interventions and whether it has been translated into relevant and well-performing jobs interventions. To answer this question, we (i) performed a portfolio review and analysis of 257 projects; (ii) carried out a structured literature review of the impact evaluations about jobs interventions; (iii) analyzed 13 country case studies; and (iv) ran a content analysis of the 18 available IPF and PforR Implementation Completion and Results Report Reviews. Overall, we found that the enhanced focus on jobs in the IDA strategy has been associated with only a slight increase in the size of the jobs portfolio but has led to a more pronounced change in the mix of jobs interventions. Jobs interventions are for the most part well designed, grounded in evidence, and often effectively combined within projects. The IDA jobs strategy’s prioritization of youth and women’s employment also resulted in more focus on these two beneficiary groups in jobs interventions. However, because of the inadequate results measurements, little is known about the effectiveness of the portfolio.

Portfolio Evolution

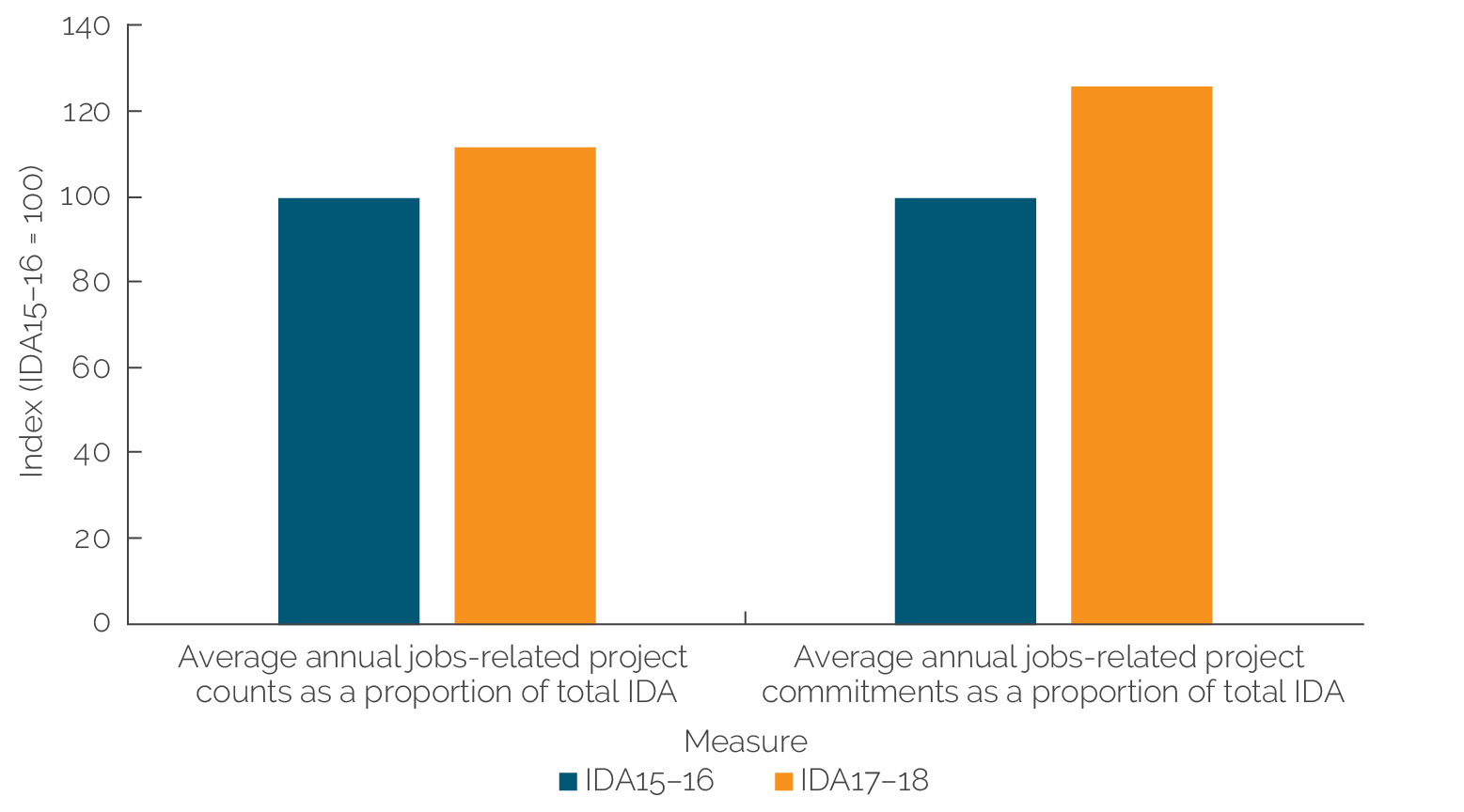

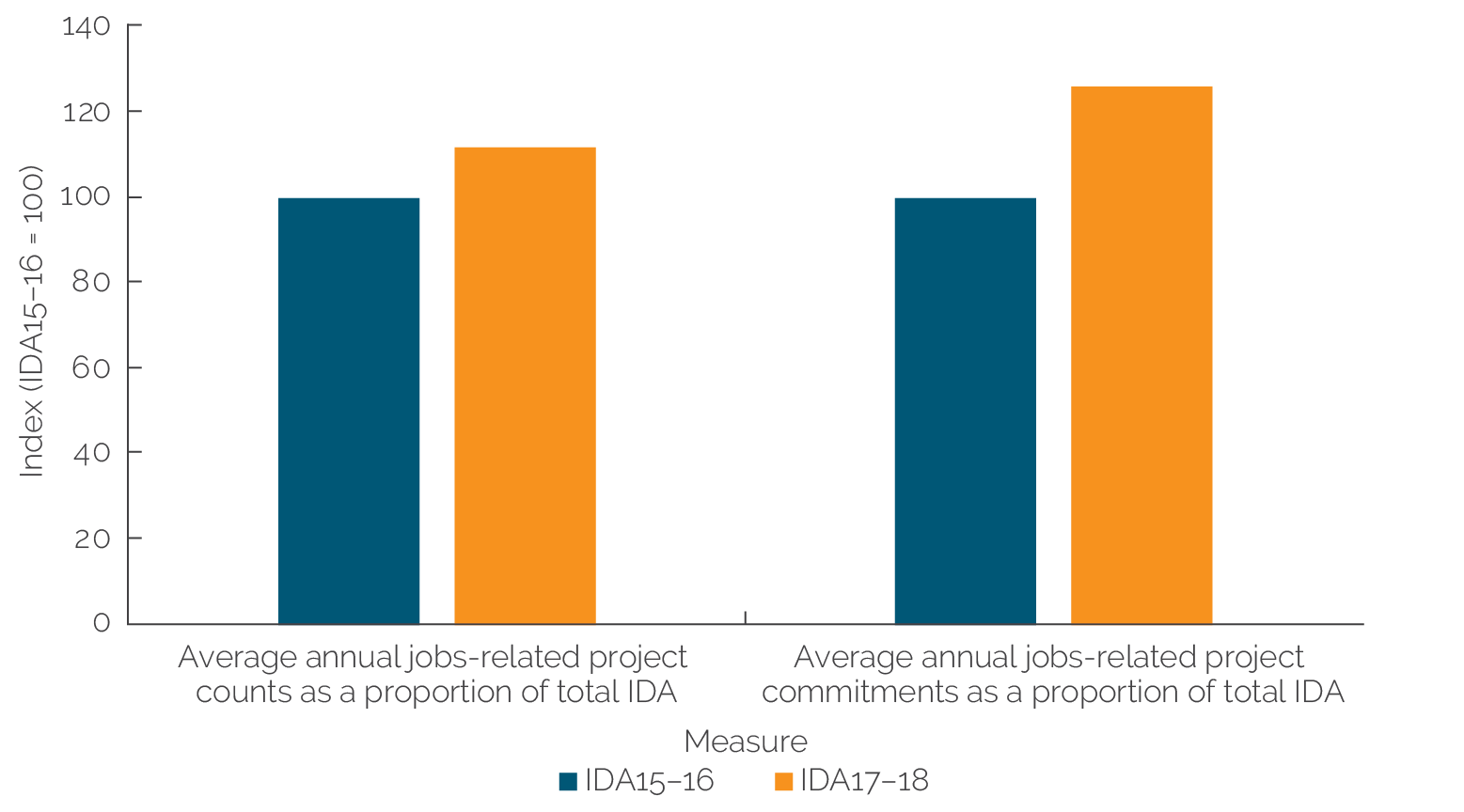

The enhanced focus on jobs in IDA strategy is associated with a slight increase in the size of the jobs portfolio. Figure 3.1 shows that IDA17 and IDA18 had higher estimated average annual shares of the IDA jobs-related portfolio in the total count and commitments of all IDA projects than IDA15 and IDA16. The share of the IDA jobs-related portfolio in the total count and commitments of all IDA projects remained stable across the three IDA Replenishment rounds examined (table 3.1).

Figure 3.1. IDA Jobs-Related Investment Project Financings and Programs-for-Results before and after the Shift in IDA Jobs Strategy

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Calculations presented are based on “synthetic” IDA jobs-related portfolios created for the purposes of comparison with the pre-evaluation period, and therefore they are not directly comparable with those for the “actual” evaluation portfolio presented in table 3.1. Thus, values are presented as an index with the first period being equal to 100 to show the change. IDA = International Development Association; IDA15, IDA16, IDA17, IDA18 = 15th, 16th, 17th, and 18th Replenishments of IDA.

Table 3.1. Share of IDA Jobs-Related Investment Project Financing and Program-for-Results Portfolio in Total IDA Projects over IDA Replenishment Cycles, FY15–22

|

IDA Replenishment Round |

Projects |

IDA Commitments |

||

|

Total (no.) |

As a share of total IDA (%) |

Total (US$, millions) |

As a share of total IDA (%) |

|

|

IDA17 |

75 |

13 |

6,486 |

13 |

|

IDA18 |

76 |

12 |

9,140 |

15 |

|

IDA19 |

76 |

14 |

9,686 |

15 |

|

Total |

227 |

13 |

25,312 |

15 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: FY = fiscal year; IDA = International Development Association; IDA17, IDA18, IDA19 = 17th, 18th, and 19th Replenishments of IDA.

IPF and PforR projects worked primarily through the labor demand and supply channels to achieve jobs-related objectives. Supply-side interventions tended to focus on skills and training for formal sector workers, and the use of small grants, microloans, and capacity building to support the self-employed and microentrepreneurs, who were more likely to be informally or vulnerably employed workers. Demand-side interventions included support to micro, small, and medium enterprise employers in both the formal and informal sectors through managerial, leadership, and psychosocial training or digital skills development. Such projects also focused on strengthening financial access through grants or venture capital to support better-paying jobs and investments in upskilling or reskilling workers to increase their productivity. When projects specifically targeted women or youth, they tended to include some form of labor intermediation, such as job fairs, matching services, or transport subsidies. Interventions to enhance labor market flexibility were rarer. They included interventions to improve labor information systems or labor code. Within agriculture, projects targeted on-farm productivity through a combination of technology transfer, capacity building, and subsidized inputs to improve outcomes for both formal and informal agricultural workers. Other projects targeted the development of the agribusiness value chain to increase production for processing or experts. These interventions aimed to improve the earnings of smallholder farmers—a critical jobs objective in itself—or the formalization of agricultural and food systems jobs.

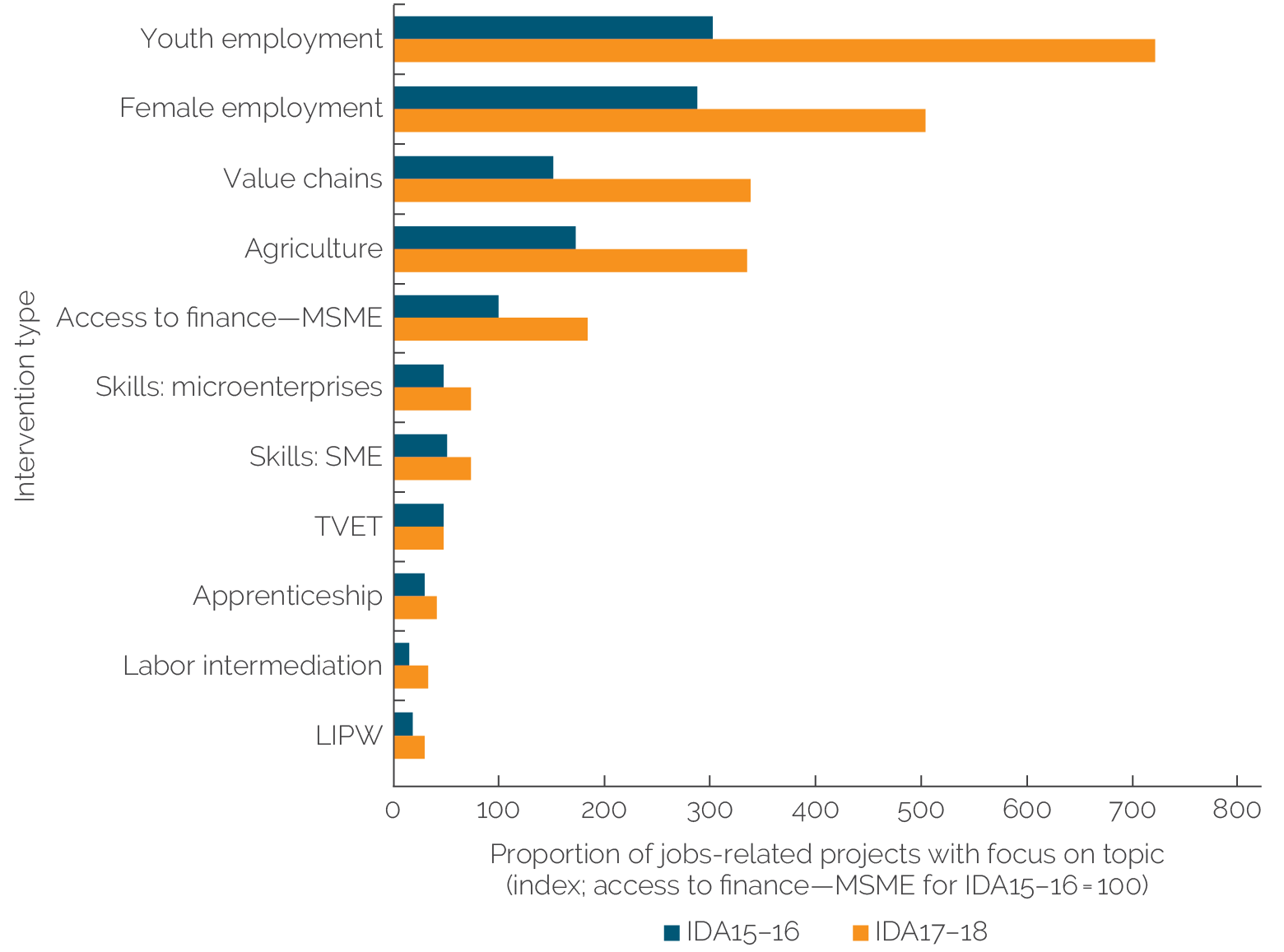

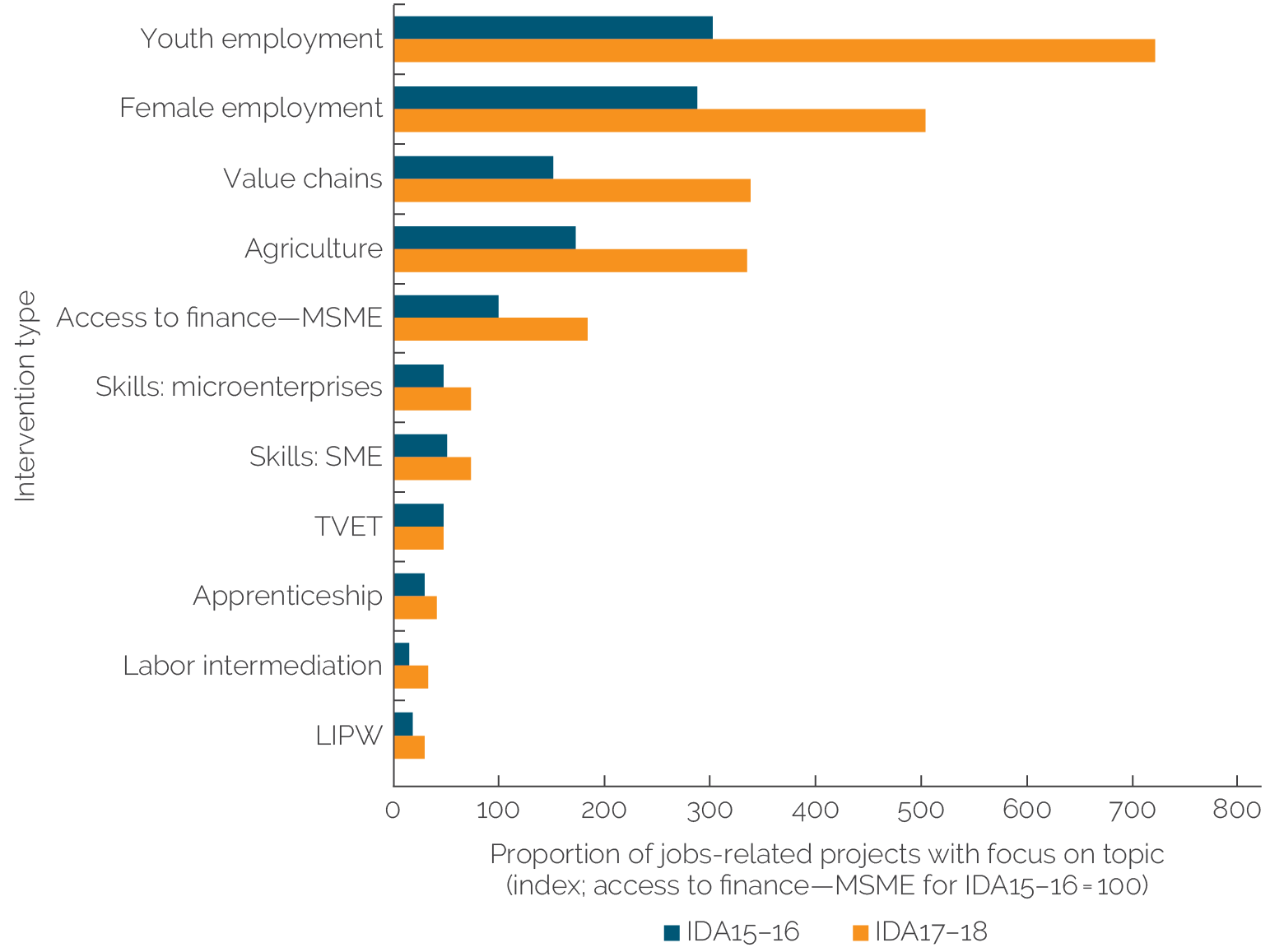

The shift in the IDA jobs strategy led to a change in the mix of jobs interventions in the portfolio. The evolution of the portfolio shows three distinct patterns, which reflected the shift in the IDA jobs strategy. First, there was a notable increase in the proportion of jobs-related projects that worked through the labor demand channel, such as the promotion of value chains, especially agricultural value chains, and business support to micro, small, and medium enterprises. Second, there was a notable increase in the proportion of jobs-related projects that sought to ensure the participation of youth and women in project activities. Third, the share of jobs-related projects that worked through the supply side remained stable across periods (figure 3.2).

In line with the evidence literature, bundling labor demand and labor supply interventions has now become common practice in the portfolio. In the IPF and PforR portfolio, 87 projects (40 percent) integrated both supply- and demand-side interventions. The literature clearly finds that interventions tended to have more impact when combined. Program effectiveness for youth was generally higher if the interventions combined multiple forms of support and offered personalized assistance and follow-up services (Kluve et al. 2019). Several such examples were found in the portfolio. In the Solomon Islands Rural Development Program II, there was a dual focus on both supply- and demand-side interventions, with income-generating skills courses and market linkages for farmers and agribusinesses. The project met both its objectives and surpassed both its targets for its indicators.

Figure 3.2. Change in Proportion of Different Types of Interventions in “Synthetic” Jobs Portfolio

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Values presented are indexed, with the value for the intervention type “access to finance—MSME” in IDA15–16 as the base (=100). For example, the value of the intervention type “youth employment” in IDA15–16 is 300 (that is, it was three times that of “access to finance—MSME” in the same period); similarly, the value for the intervention type “female employment” in IDA17–18 was 500, implying that it was five times that of “access to finance—MSME” in IDA15–16. The actual proportions are not reported because they are based on “synthetic” portfolios and are therefore not fully aligned with values computed for the actual evaluation portfolio for the IDA17–18 period. IDA15, IDA16, IDA17, IDA18 = 15th, 16th, 17th, and 18th Replenishments of the International Development Association; LIPW = labor-intensive public works; MSME = micro, small, and medium enterprise; SME = small and medium enterprise; TVET = technical and vocational education and training.

However, working across sectors to fully integrate supply- and demand-side interventions—as recommended by jobs diagnostics—has been hard to translate into practice. The objective of the jobs diagnostic is to guide policy makers and development practitioners in the design of country-specific jobs strategies comprising policy reforms, regulations, and investments to improve labor incomes and working conditions (Lachler and Merotto 2020). However, the portfolio review revealed that various GPs continued to target different beneficiary pools and pursue different jobs-related objectives rather than exploiting synergies and seeking scale. The extent of estimated cross-GP collaboration for projects in the evaluation portfolio varied depending on the specific pairs of GPs considered, with pockets of strong collaboration along with some that could potentially be strengthened. For the four GPs that led most jobs projects (Agriculture and Food; Education; Finance, Competitiveness, and Innovation; and Social Protection and Jobs), table 3.2 shows the proportions of their projects supported by the other GPs. For some GP pairs, there is also a higher degree of reciprocity than for others. For example, Finance, Competitiveness, and Innovation supported 28 percent of the Agriculture and Food GP’s projects, and the latter supported 21 percent of the former.

GPs could better leverage each other’s expertise to design interventions with more impact. Collaboration data, and evidence from case studies on the prevalence of demand- and supply-side interventions in projects, show that collaboration between the Agriculture and Food and the Finance, Competitiveness, and Innovation GPs, which collaborated in about one-quarter of projects, was an important factor in the uptake of agribusiness and value chain projects. For example, the jointly designed Nepal Rural Enterprise and Economic Development Project strengthened rural market linkages, incentivized regulatory improvements, and financed services and infrastructure in support of producer organizations, agribusiness SMEs, and agritech start-ups. One potential barrier to cross-GP collaboration was likely to be obstacles in the way of (or lack of incentives for) collaboration with GPs across the Practice Groups, the administrative divisions (vice presidential units) within which the various GPs operate. The extent of cross–Practice Group collaboration, based on the same measures used for cross-GP collaboration, is presented in table 3.3 for the entire evaluation portfolio. As can be seen from this table, for the Human Development and Sustainable Development Practice Groups, there was more collaboration within than across Practice Groups.

Interviews with country teams pointed to barriers to exploiting synergies across jobs projects through a more integrated approach. Collaboration was hindered, for example, by corporate incentives favoring certain GPs and task team leaders lead responsibilities, including through greater control of budgetary resources. There were also significant differences in perspectives between GPs on how best to address jobs objectives. Finally, the jobs agenda is not managed in a centralized manner within most client governments, which can contribute to a fragmented policy dialogue, which is not conducive to a more integrated approach within the World Bank, where different GPs may have different government interlocutors.

Table 3.2. Cross–Global Practice Collaboration on Jobs-Related Projects by Selected Global Practices

|

Lead GP |

Projects (no.) |

Supporting GP |

|||

|

Agriculture and Food (%) |

Education (%) |

Finance, Competitiveness, and Innovation (%) |

Social Protection and Jobs (%) |

||

|

Agriculture and Food |

78 |

n.a. |

0 |

28 |

5 |

|

Education |

34 |

9 |

n.a. |

12 |

29 |

|

Finance, Competitiveness, and Innovation |

34 |

21 |

15 |

n.a. |

9 |

|

Social Protection and Jobs |

42 |

10 |

17 |

21 |

n.a. |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: GP = Global Practice; n.a. = not applicable.

Table 3.3. Collaboration across Practice Groups on Jobs-Related Projects

|

Practice Groups for Lead GP |

Projects (no.) |

Practice Groups for Supporting GP |

||

|

Equitable Growth, Finance, and Institutions (%) |

Human Development (%) |

Sustainable Development (%) |

||

|

Equitable Growth, Finance, and Institutions |

34 |

24 |

24 |

38 |

|

Human Development |

78 |

24 |

35 |

21 |

|

Sustainable Development |

103 |

29 |

17 |

52 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The newly formed Infrastructure Practice Group is excluded from this table (N = 11). GP = Global Practice.

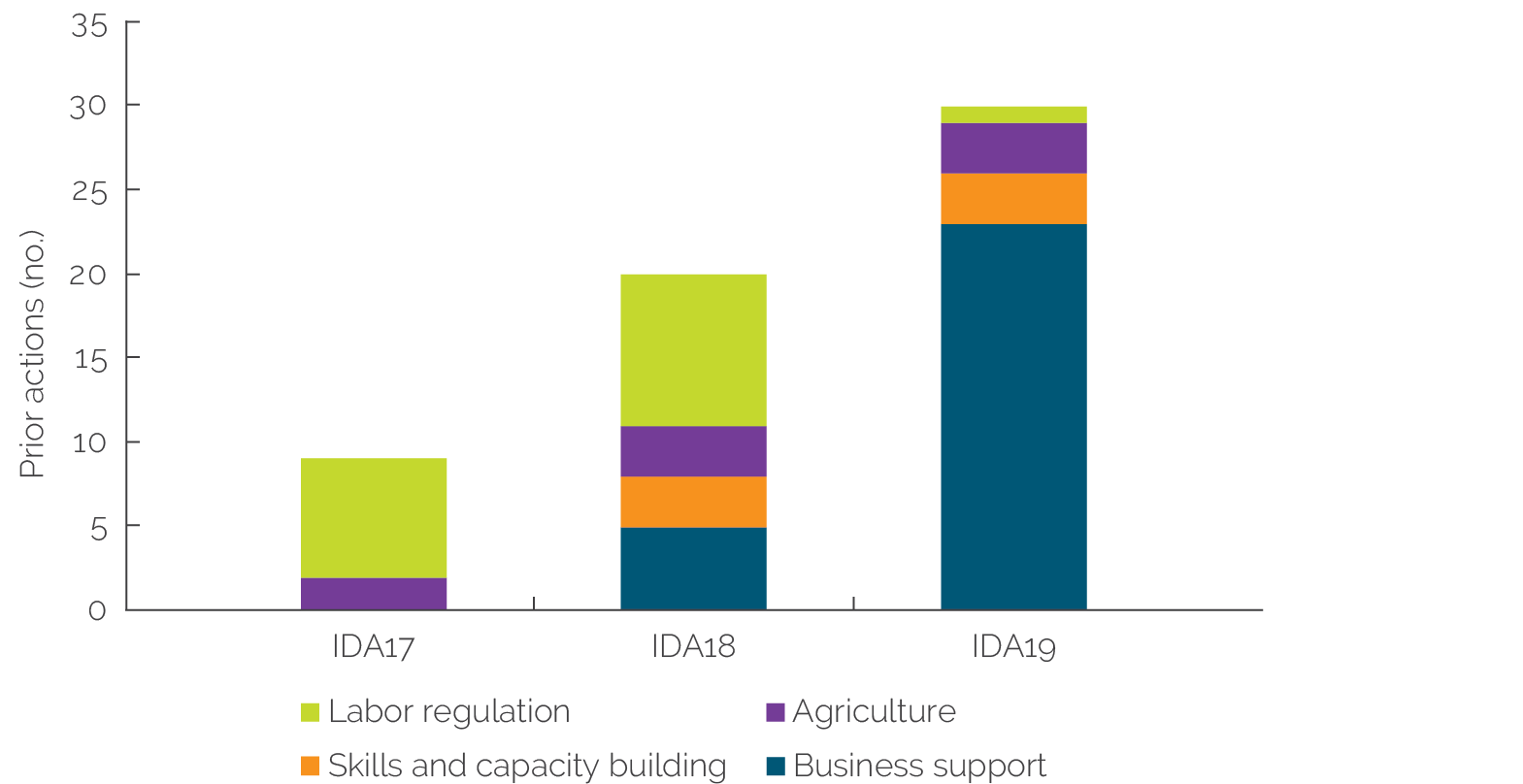

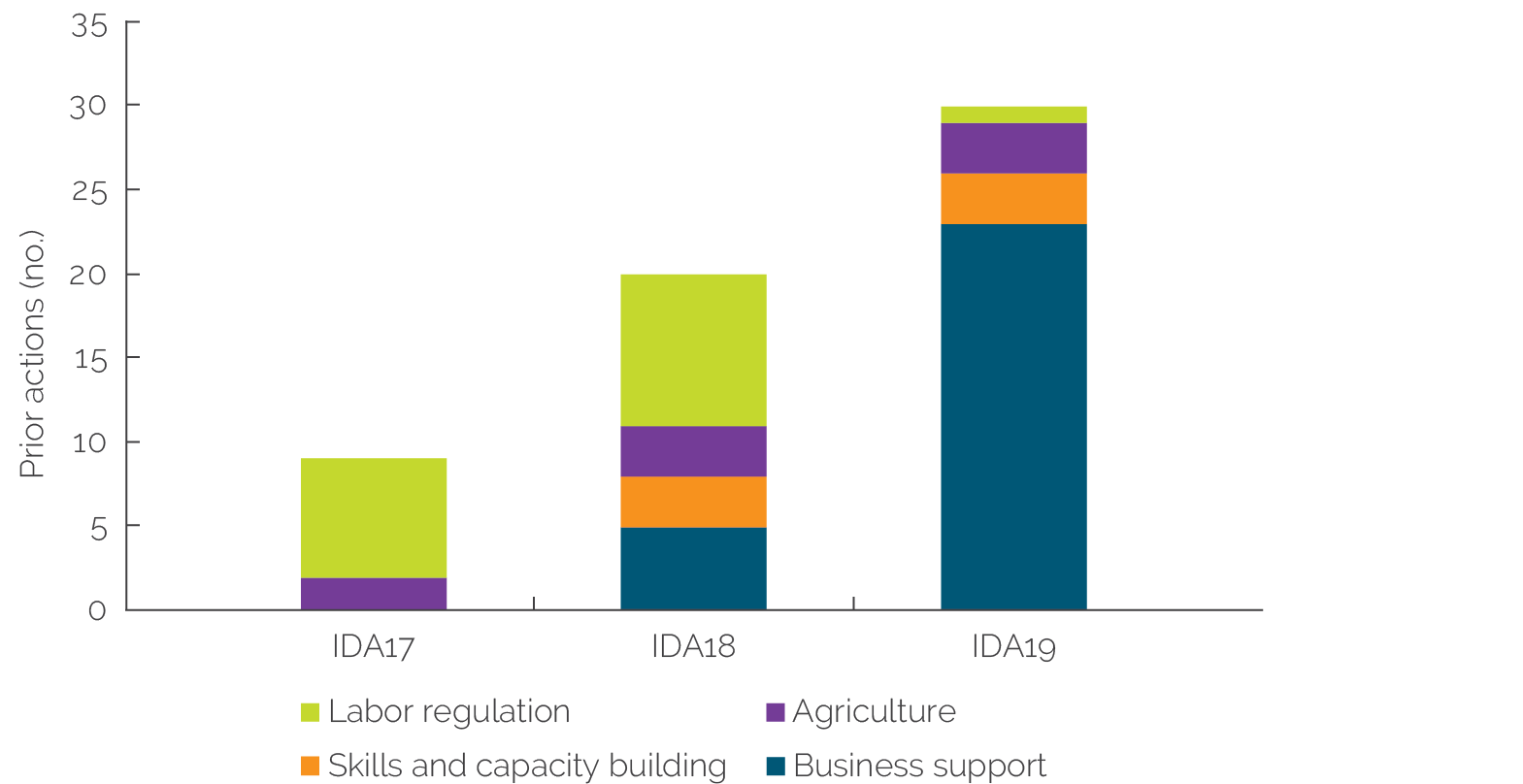

Although the use of development policy financing in direct support of jobs-related objectives was infrequent, the number of prior actions supporting jobs-related objectives has increased steadily across IDA Replenishments. Policy reforms mainly focused on labor regulation, gender discrimination, financial access, and agriculture, with DPO engagement on agriculture tapering off in IDA19. Figure 3.3 describes DPO prior actions by type of jobs intervention, especially through reforms targeting gender-based discrimination and youth development. For instance, in Niger, the DPO supported technical and vocational education and training (TVET) reform and introduced a national policy on dual apprenticeship training to promote youth employment, including through prior actions supporting the adoption of a new labor code that describes the legal framework for dual apprenticeships. In terms of mapping to channels of intervention, the overwhelming majority of DPO prior actions relate to labor demand, including those classified as agriculture-related interventions. IEG found no evidence of a shift in mapping of prior actions across IDA Replenishment rounds.

Figure 3.3. Top Areas of Interventions for Prior Actions across IDA Replenishments

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: IDA17, IDA18, IDA19 = 17th, 18th, and 19th Replenishments of the International Development Association.

Development policy financing was used adequately in several operations to contribute to jobs outcomes through necessary changes in labor market regulations. Concrete, well-articulated prior actions often contributed to jobs outcomes. For example, a DPO for Uzbekistan supported both labor mobility and formalization of work contracts for part-time and temporary workers through a prior action to simplify contracting procedures. The associated results indicator tracked the number of part-time and temporary employees with formal contracts. In Bangladesh, the jobs development policy credit built on collaboration with IFC and the International Labour Organization to support improved workplace safety and an improved labor code, which introduced, among other important provisions, penalties for sexual harassment and gender-based violence. The associated results indicator related to the number of complaints dealt with, including those related to sexual harassment and gender-based violence. In Senegal, the instrument was used to outlaw discrimination in the workplace based on gender, pregnancy, or lactation. The associated results indicator tracked the increase in share of female-led firms awarded public procurement contracts.

Appendix D contains additional examples of DPO jobs-related prior actions and associated results indicators.

Design of Jobs Interventions

Overall, the choice and design of jobs interventions was well informed by analysis. The evaluation triangulated information from the portfolio review, the structured literature review, IEG validations of staff self-evaluations, and case studies to assess the strength of the analytical underpinning of interventions and the quality of their design. Table 3.4 summarizes the findings and shows that the majority of jobs interventions supported by IDA were backed by evidence from impact evaluations.

Table 3.4. Types of Jobs Interventions in the Portfolio and Strength of Evidence

|

Channels |

Type of Jobs Interventions |

Strength of Evidence |

Projects (no.) |

|

Labor supply |

Skills: training and skills building for microentrepreneurs; TVET; apprenticeships |

Mixed evidence |

80 |

|

Measures to support labor force participation (for example, childcare; outreach to women and marginalized groups) |

Mixed evidence |

10 |

|

|

Labor regulations (for example, antidiscriminatory rules; antiharassment; incentivizing formalization) |

Limited evidence |

3 |

|

|

Labor demand |

Support to agriculture value chains and agribusiness |

Strong evidence |

28 |

|

Support to agricultural productivity (for example, inputs, seeds, and technology) and extension services |

Strong evidence |

43 |

|

|

Business support and capacity building of SMEs |

Strong evidence |

33 |

|

|

Access to finance for microentrepreneurs, SMEs, and MSMEs (through small loans and grants) |

Strong evidence |

65 |

|

|

Labor-intensive public works, including with a design focused on productive community assets |

Mixed evidence |

12 |

|

|

Both |

Combination of multiple labor supply and demand interventions (for example, skills and extension services, technology transfer, and finance) |

Strong evidence |

87 |

|

Labor flexibility |

Labor market information systems; labor intermediation services; employment exchanges; job search assistance; transport subsidies |

Limited evidence |

19 |

|

Labor codes; worker safety and health |

Limited evidence |

1 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The table overlays evidence from the portfolio analysis and the structured literature review. The strength of evidence was assessed based on the search in the literature related to jobs objectives. MSME = micro, small, and medium enterprise; SME = small and medium enterprise; TVET = technical and vocational education and training.

Labor Demand Interventions

The shift in jobs strategy led to an increase in interventions to enhance labor demand, especially support to sector-specific value chains. Consistent with recommendations from jobs diagnostics, the World Bank increased its efforts to remove bottlenecks in sectors with high potential for private sector–led job creation. Portfolio data show that 177 projects (69 percent of the portfolio) supported labor demand interventions. A deep dive into the evolution of country portfolios in 13 IDA countries also reveals an increased incidence of value chain and sector-specific projects. For example, the value chain operations in Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Kenya, and Sierra Leone were the first of their kind in the countries. These projects typically combined regulatory simplification with business support services and access to finance, and their objective was to enhance economic diversification through targeted support to specific value chains. They were often appropriately tested in situ before committing to financing. The Kenya Industry and Entrepreneurship Project was informed by a prior impact assessment of an in-country short-term, applied, intensive technology bootcamp and drew on findings from a trust-funded open innovation pilot.

A notable shift toward support to agribusiness took place to realize IDA’s priority of increasing jobs in the food system. Twenty-eight projects in the portfolio focused on promoting agribusiness or agricultural value chains. Since IDA18, country portfolios tend to combine projects with more conventional interventions to enhance agricultural productivity (through inputs and technology transfer), with complementary projects specifically targeting agribusiness SMEs. This shift is supported by evidence from the literature (Creevey, Dunn, and Farmer 2011; Dunn 2014; Humphrey and Navas-Alemán 2010; Rutherford et al. 2016). Examples from case studies show the benefits of combining both approaches. For example, in Sierra Leone, the Smallholder Commercialization and Agribusiness Development Project was complemented by the Agro-Processing Competitiveness Project, whose objective was to improve the enabling environment for agribusiness by simplifying regulations and providing business development services and capital investment grants to firms.

Several factors that would support better results for this type of intervention can be inferred from IEG validations of staff self-evaluations. When both farmers and processors were involved along the entire agricultural value chains, ownership and results tended to be better. Flexibility in the implementation of agricultural value chain projects was crucial to meet the needs of farmers, especially in the formation of producer groups, which play a crucial role in facilitating market access for agricultural products. The use of direct payments of grants to beneficiaries through mobile money can enhance local ownership and accessibility. Supporting nonfarm enterprises empowered beneficiaries to shift their household income away from insecure and low-paid wage employment, providing a pathway out of poverty.

Labor Supply Interventions

Projects addressing labor supply constraints did not change fundamentally, with a prevalence of TVET and stand-alone skills development projects, despite mixed evidence that such interventions have sustained impact on jobs outcomes. In the portfolio, 80 projects focused on enhancing the skills and capacities of (future) workers through apprenticeship, or TVET, or on-the-job training. Typical skills enhancement interventions, especially TVET, continue to rely on public training institutes and emphasize curriculum development through consultation with private employers without attempting to stimulate markets for training providers or strengthen their accountability for results. For example, TVET projects implemented before IDA17 in low-income and lower-middle-income countries, such as Bangladesh and Ghana, had limited impact, yet newer projects largely replicated the same design. The literature shows that getting technical and vocational education right requires adequate institutional capacity (World Bank, UNESCO, and ILO 2023), and in many lower-middle-income countries, the link between technical and vocational education and the labor market is currently broken. Case studies show that learners, especially women, face obstacles when looking for adequate jobs after completing technical and vocational education. They are often trapped in low-skilled jobs because of occupational segregation or cultural and social norms. There are limited incentives for the providers of technical and vocational education to respond to the needs of the labor market because their accountability to learners and teachers remains limited.

Conversely, some interventions, such as apprenticeships, show evidence of having achieved targeted outcomes but were rare in the portfolio, except in Western and Central Africa. The portfolio had only 27 apprenticeship projects, two-thirds in Western and Central African countries. A series of evaluations reported the positive effects of apprenticeships on a range of socioeconomic and well-being outcomes (Alfonsi et al. 2020; Crépon and Premand 2019), although effects for young women are less encouraging (Cho et al. 2013). The skills acquired during apprenticeship programs seem to lead to better employment outcomes. For example, the Bangladesh Recovery and Advancement of Informal Sector Employment project supported on-the-job training under informal apprenticeships through stipends to apprentices, training in life skills, testing and certification of apprentices’ knowledge, and payments to expert craftspeople for hosting apprentices (box 3.1).

Box 3.1. Example of Apprenticeship Interventions

The Niger Skills Development for Growth Project aims to improve the effectiveness of formal technical and vocational training, short-term skills development, and apprenticeship programs in priority sectors. This additional financing scales up the parent project approved in November 2013 and focuses mainly on agriculture and livestock.

The project development objective (PDO) indicator capturing progress on improving short-term skills development and apprenticeship programs has been exceeded. The percentage of out-of-school youth completing dual apprenticeship training programs as a result of the project’s activities was targeted to be 70 percent by November 2023 and is currently 81 percent. The share of women and girls among these youth was targeted to be 40 percent and is currently 48 percent.

The Central African Republic Investment and Business Competitiveness for Employment Project aims to implement reforms to enable investment, improve access to credit, and support targeted small and medium enterprises and young workers. The PDO indicator—certified apprentices with an active economic activity six months after the program completion—measures progress against supporting workers and captures the share of trainees who secure employment at the business in which they were apprenticed. No progress has been reported so far—targets for March 2027 are 50 percent overall, of which youth are targeted to be 50 percent and women and girls 40 percent.

The Chad Skills Development for Youth Employability Project aims to improve access to skills training and labor market outcomes for project beneficiaries and strengthen the technical and vocational education and training sector in Chad. Component 2 supports internships to improve the school-to-work transition and the expansion of opportunities for apprenticeships. The PDO indicator—share of beneficiaries of skills development programs who are employed (wage or self-employment) within six months of completion—captures progress toward the objectives through all activities, including apprenticeships and internships.

The Ghana Jobs and Skills Project aims to support skills development and job creation. Component 1 supports apprenticeship training for jobs. The PDO indicator capturing progress against the objective is the share of apprenticeship training program participants who complete the program and have jobs at least six months after completion. Targets do not seem ambitious relative to baseline, with an increase of only 10 percentage points envisaged, including in terms of share of women and girls successfully completing the program.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group based on Project Appraisal Documents.

In line with the literature, skills enhancement projects routinely bundled multiple interventions to enhance effectiveness. In the nine IEG validations of staff self-evaluations that assessed the performance of skills enhancement projects, the design of labor supply interventions was rated high, with clear lines of sight directly to jobs in seven out of nine projects and with appropriate bundling of multiple interventions. Some projects also used technology adequately to address access barriers. For example, in Pakistan, training sessions reached 396,530 farmers by using YouTube to stream agricultural training videos through mobile agricultural cinemas. Two other factors were found to enhance the likelihood of implementation success in skills interventions. First, a strong outreach and recruitment effort is deemed necessary to ensure the meaningful participation of youth in programs, and community engagement with local leaders is needed to promote the involvement of minority communities. Second, a strong public-private collaboration is needed for the development and maintenance of relevant skills programs, and performance-based contracts can enhance dialogue, transparency, and results.

Women and Youth Employment Interventions

The IDA jobs strategy prioritization of youth and women’s employment also resulted in more focus on ensuring the participation of these two beneficiary groups in jobs interventions. Jobs interventions more routinely seek to improve the gender balance among beneficiaries. Projects now systematically seek to reach women in jobs interventions, and they more routinely use specific incentive mechanisms to do so. For example, in Kenya and Sierra Leone, skills development projects used payment bonuses to service providers to try to reach a 50 percent female beneficiary ratio. In Côte d’Ivoire, the competitive value chain operation contained a small module to finance childcare services and personal initiative training for women. The emphasis on tracking gender-disaggregated indicators also means that more is known about whether targets are achieved or not.

Despite a growing body of evidence from impact evaluations, and the magnitude of the challenge, women-specific employment interventions remain infrequent in the portfolio. The Africa Gender Innovation Lab and the World Bank’s Gender team have conducted several studies to collate evidence on interventions that improve female labor force participation rates, support female entrepreneurship, and reduce gender differentials in income and employment vulnerability (Halim, O’Sullivan, and Sahay 2023; Sahay 2023; Ubfal 2023). These evaluations show promising evidence of successful women-specific projects. For example, the Sahel Adaptive Social Protection Project, which covers multiple countries and is mainly focused on women, found positive, significant, and persistent impact on off-farm business revenues and savings. Multiple interventions were undertaken, such as cash grants, savings associations, and training (life skills, micro entrepreneurship, and coaching and mentoring), as well as community sensitization on aspirations and social norms. Impact was high across different contexts—from rural Niger and Mauritania to urban Senegal. The Africa Gender Innovation Lab conducted randomized controlled trials in Ethiopia, the Republic of Congo, and Uganda to test interventions seeking to encourage women entrepreneurs to enter male-dominated sectors and showed that specific information-sharing practices about better opportunities had the most impact. The provision of childcare has been shown to lead to significantly higher female participation, employment, financial resilience, and savings. Yet women-specific interventions remain rare in the portfolio, with only 10 having specific interventions to ensure childcare and very few working on rules and social norms to address gender gaps in employment.

The World Bank has used accrued evidence from impact evaluations to effectively adapt the design of youth employment interventions. IEG’s 2012 evaluation on youth employment noted the absence of a comprehensive approach to youth employment projects (World Bank 2012b). Since then, significant progress has been made in ensuring that youth employment projects bundle multiple supply-side interventions in line with what the literature recommends. Interventions that target youth tend to combine skills development, TVET, and enterprise support. Although the benefits of training programs on youth are rather weak when training is used alone (Fox and Kaul 2018; Kluve et al. 2019), a recent meta-analysis reviewing estimates from more than 200 studies found that training programs combining multiple forms of support and offering personalized assistance and follow-up services are very effective (Kluve et al. 2019; Puerto et al. 2022). Examples of such combinations are increasingly common in the portfolio, with a trend toward bundling cash transfer, labor-intensive public works, and entrepreneurship programs, and a growing recognition of the need to encourage graduation from safety nets through job creation (for example, Ghana, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Sierra Leone). In FCV countries, youth employment interventions are increasingly common and getting better at ensuring fairness and avoiding elite capture in beneficiary selection (for example, the Democratic Republic of Congo).

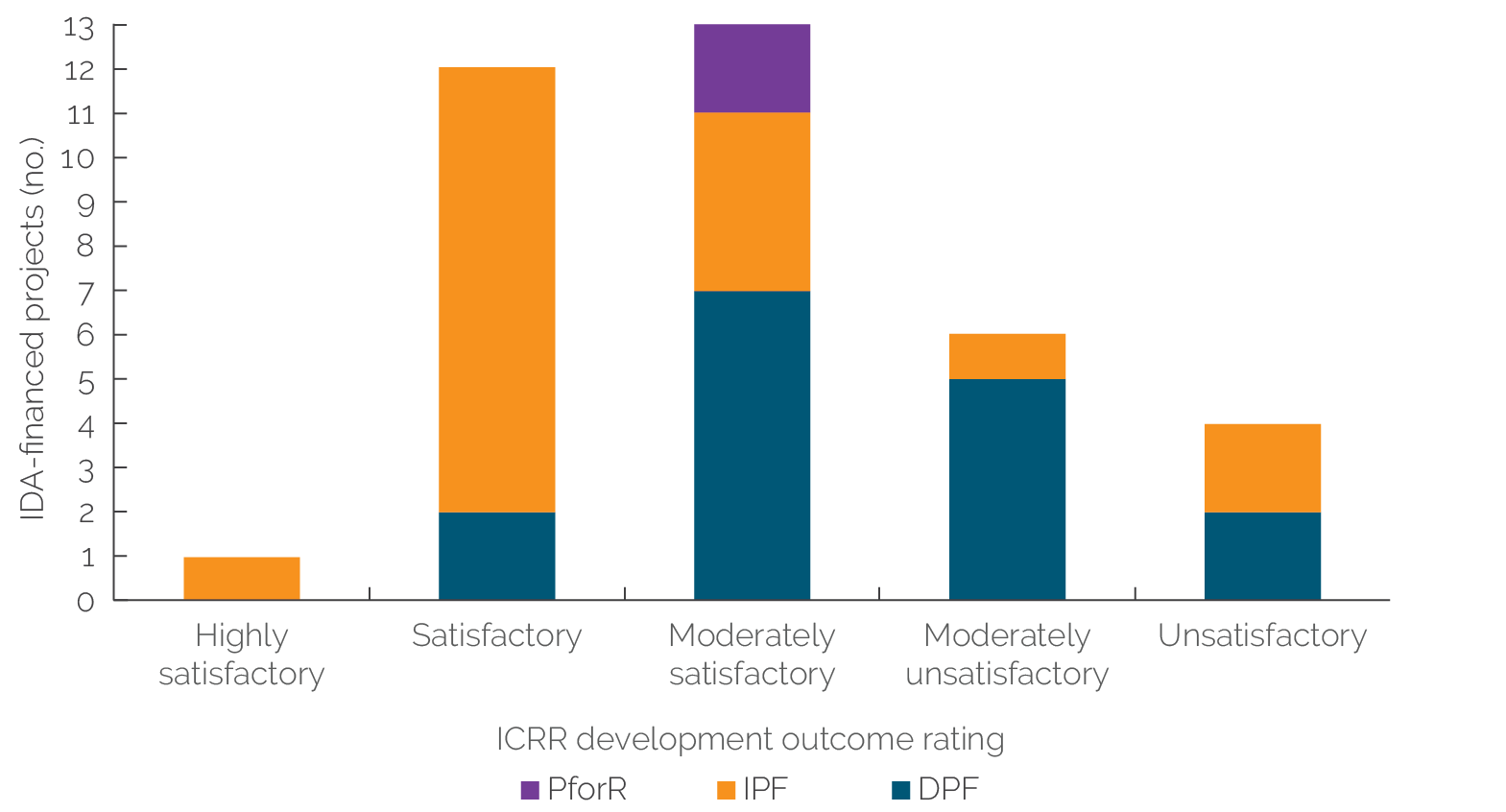

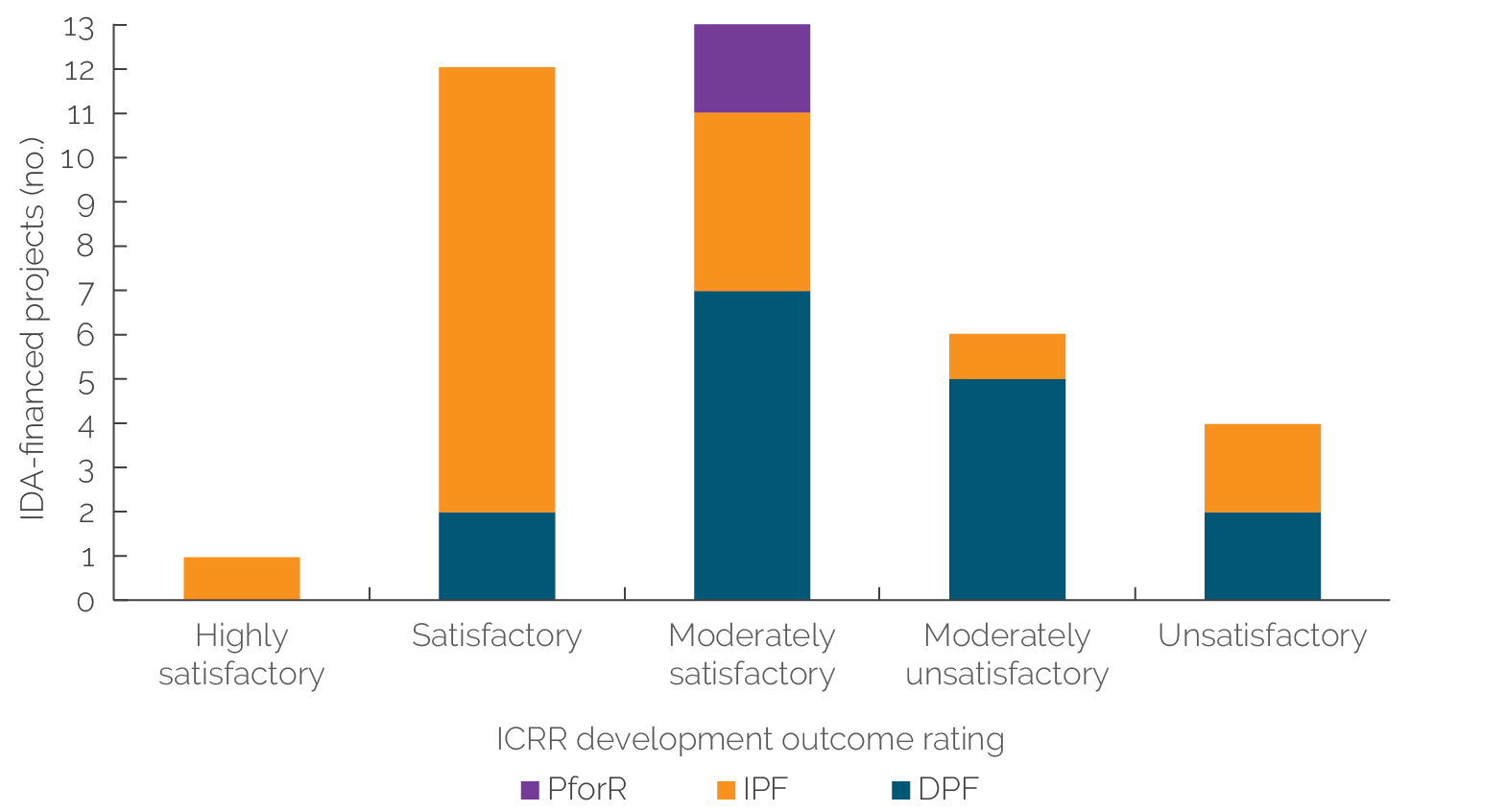

Performance

Based on the limited available data, the performance ratings of the closed projects in the evaluation portfolio were slightly better than those of the rest of the IDA portfolio. Given that the evaluation period starts in FY15, relatively few closed projects with validated outcome ratings are available. As shown in table 1.1, there were only 43 closed IPF projects, and IEG-validated outcome ratings were only available for 18 of these at the time of writing. Of the 18, 15 (83 percent) were rated moderately satisfactory or above (figure 3.4). In comparison, 72 percent of the 105 nonjobs-related closed IPF projects (with IDA financing) with IEG-validated outcome ratings were rated as moderately satisfactory or above. This indicates a relatively better performance of the jobs-related project portfolio compared with the rest of the IDA portfolio. To complement the evidence from the limited set of IEG validations of staff self-evaluations, we also conducted an analysis of project indicators and found that 75 percent of jobs-related indicators in closed projects achieved their targets (table 3.5).

Figure 3.4. Project Counts by Outcome Ratings in Implementation Completion and Results Report Review

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: DPF = development policy financing; ICRR = Implementation Completion and Results Report Review; IPF = investment project financing; PforR = Program-for-Results.

Table 3.5. Indicator Analysis

|

Indicator Type |

Projects (no.) |

No Progress (%) |

Not on Track (%) |

On Track (%) |

Achieved (%) |

|

By indicator category: All projects |

|||||

|

Outcome |

42 |

29 |

14 |

7 |

50 |

|

Output |

85 |

20 |

11 |

22 |

47 |

|

Total |

127 |

2 |

12 |

17 |

48 |

|

By indicator category: Closed projects |

|||||

|

Outcome |

11 |

9 |

9 |

0 |

82 |

|

Output |

29 |

3 |

0 |

24 |

72 |

|

Total |

40 |

5 |

3 |

18 |

75 |

|

By indicator category: Active projects |

|||||

|

Outcome |

31 |

35 |

16 |

10 |

39 |

|

Output |

56 |

29 |

16 |

21 |

34 |

|

Total |

87 |

31 |

16 |

17 |

36 |

|

By indicator type: All projects |

|||||

|

Intermediate results indicator |

63 |

16 |

11 |

14 |

59 |

|

PDO indicator |

64 |

30 |

13 |

20 |

38 |

|

Total |

127 |

23 |

12 |

17 |

48 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The sample of indicators included in this analysis covers 46 projects total: 33 active and 13 closed. The methodology is described in appendix B. PDO = project development objective.

The implementation performance of the active projects followed a similar pattern. To understand the performance of active projects in jobs-related versus nonjobs-related IDA-financed projects, IEG analyzed the proportion of projects in the portfolio that were classified as “actual problem projects” at any time during the 24 months between July 2021 and June 2023. The measure, calculated for a subset of projects from each group where data were available for all 24 months, is presented in table 3.6. It can be seen that the set of active jobs-related projects fared slightly better than the rest of the IDA active portfolio. However, the indicator analysis showed that targets for only half of the jobs-related indicators in active projects that were past their Mid-Term Review were on track to be achieved, and about one-third of indicators had made no progress toward their targets.

Table 3.6. Extent of Problem Projects in the Active IDA-Financed Jobs-Related and Nonjobs-Related Portfolios, FY15–22

|

Type |

Projects (no.) |

Projects Classified as “Actual Problem Projects” Any Time during June 2021 and June 2023 (no.) |

Proportion of Projects Classified as “Actual Problem Projects” Any Time during June 2021 and June 2023 (%) |

|

Jobs related |

105 |

26 |

25 |

|

Not jobs related |

624 |

245 |

39 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: FY = fiscal year; IDA = International Development Association.

Several factors helped the implementation of jobs interventions in IDA. Based on case studies evidence and mining of Implementation Completion and Results Report Reviews, the following factors, not all unique to jobs interventions, emerged as enabling successful implementation. Projects with strong institutional support for public-private partnerships and dialogue paved the way for effective collaboration between government and private sector interests. Partnerships are not limited to the public and private spheres only. Extensive diagnostic work and collaboration among donors also provided a solid foundation for project planning and implementation. Having a balance between short- and long-term reform needs careful identification of achievable targets based on different timelines. The implementation of ambitious reforms could involve phasing in key interventions and reforms. When lessons from previous projects informed subsequent phases, especially in low-capacity or FCV environments, projects were more likely to succeed, especially when they adapted to specific security and fragility challenges. For example, in Côte d’Ivoire, the World Bank’s involvement began largely with labor-intensive public works and cash transfers in the immediate postconflict period but then evolved to include entrepreneurship training and business development services for individuals to encourage graduation from the social safety net.

Three factors were recurrent in jobs interventions with failed implementation. Weaknesses in project preparedness led to the abandonment or delay of interventions, mostly because of unforeseen implementation costs, underestimated staffing costs, or capacity issues in implementation agencies. Similarly, frequent changes in management, staff, and personnel also yielded the same result. Next, political risks related to political uncertainties, especially during election cycles, were not fully accounted for and had a significantly negative impact on projects. At times, high reliance on the government or implementing agencies with low capacity to implement complex projects resulted in failure. Finally, the pandemic significantly affected project implementation and coordination because of lockdowns, breaks in operational continuity, and health risk factors.

Jobs-related prior actions in DPOs were deemed relevant, but only one-third of operations achieved the targets associated with their results indicators. A total of 33 DPOs fell within the scope of this evaluation (that is, those with at least one jobs-related prior action approved under IDA17, IDA18, or IDA19), and of those, 22 operations have been validated or evaluated by IEG. The majority of jobs-related prior actions in these DPOs were rated satisfactory for relevance, with almost all rated at least moderately satisfactory. This suggests that prior actions supporting jobs-related objectives were part of a coherent and well-articulated results chain and represented meaningful progress along the results chain to the associated jobs objective. With regard to results indicators measuring progress toward jobs objectives, 16 out of 22 results indicators were rated at least moderately satisfactory for relevance. However, just over one-quarter of results indicators were given a rating of moderately unsatisfactory or below for relevance, implying that they either inadequately captured the impact of the associated prior action or inadequately measured progress toward the associated objective. In terms of results, over one-third (38 percent) of jobs-related results indicators had an achievement rating of high (that is, targets were either fully or mostly achieved), whereas just over half (56 percent) had an achievement rating of modest or negligible, suggesting little impact from the associated prior action on progress toward the associated objective.

Several factors contribute to shortcomings in DPO achievements in reaching jobs objectives. In several DPOs, there was a mismatch between the ambition of the reform and the institutional capacity to implement it. For example, in Tanzania, the Business Environment and Competitiveness for Jobs DPO pursued too many objectives, and in the absence of a strong political backing for the reform agenda from the newly elected administration, achievements were modest, and the subsequent operations in the series were canceled. In Burkina Faso, the Fourth Growth and Competitiveness Credit DPO had a large number of unrelated prior actions, which undermined the achievement of results and made it difficult to monitor, prioritize, and focus implementation on the most critical areas.

Shortcomings in the data available to measure progress inhibited the assessment of outcomes from World Bank–supported jobs interventions. An assessment of the results indicators in projects and operations approved during the evaluation period highlights that the majority of indicators continue to capture outputs and not outcomes. The lack of comprehensive labor market information on a national scale also complicates robust tracking of progress toward jobs-related objectives and the measurement of indirect impacts of interventions beyond direct project beneficiaries. This suggests a clear need for enhanced measurement strategies and data collection mechanisms to adequately capture progress toward jobs-related objectives. A detailed review of indicators by type of intervention reveals the limitations of indicators in capturing jobs outcomes. Table 3.7 includes examples of outcome-oriented indicators as follows:

- For skills development projects, indicators typically tracked graduation or completion from training and occasionally tracked the probability of employment around the time of or within six months of project closing. A relatively small number of projects tracked the private sector relevance of TVET programs—for example, through curriculum design with industry participation—but typically did not track improvements in job quality (salary, benefits, or contractual security), private sector provision, or co-financing of training.

- For business and employer support programs, indicators mainly tracked financing or investment raised and business performance (sales, revenue, and number of beneficiaries).

- For agriculture support and agribusiness projects, indicators mainly tracked productivity (for example, yield per hectare, fall in harvesting losses, increasing share of processed commodities, increase in profitability, and adoption of technology and innovation); improving value chains (for example, market linkages, value of exports, yield increases in specific value chains, percentage of farmers selling produce in the market, and percentage of farmers selling produce in value-added form); access to finance (for example, new accounts opened by farmers or firms at financial institutions and SME action plans receiving funding for business expansion); and complying with standards (for example, SMEs compliant with international standards). Indicators tracking productivity were by far the most common.

Table 3.7. Examples of Jobs Outcome Indicators by Types of Interventions

|

Indicator |

Interventions |

|

Value chain or MSME support |

|

|

Skills development |

|

|

Entrepreneurship and livelihoods |

|

|

Agriculture and agribusiness |

|

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: MSME = micro, small, and medium enterprise.

Similar challenges affect monitoring of the impact of several DPO prior actions, with results frameworks having significant shortcomings. In Afghanistan’s 2020 Incentive Program Development Policy Grant, however, data scarcity at the time of project evaluation meant that detailed information on results indicators was lacking for several key areas, even areas where regular policy dialogue was already happening. Similarly, in Benin, the First Fiscal Reform and Growth Credit did not integrate monitoring and evaluation into government systems because of the lack of proper definition of some indicators from the outset. In Burkina Faso, the Fourth Growth and Competitiveness Credit DPO saw several delays in the implementation and resourcing of the monitoring and evaluation framework, which in turn resulted in the delay of the identification of problems and therefore the application of solutions.