The World Bank Group’s 2018 Capital Increase Package

Chapter 3 | Priority Area 2: Leading on Global Themes

Highlights

The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the International Finance Corporation both made excellent progress implementing their global themes capital increase package commitments and achieved most of their targets, particularly for gender and climate change. For example, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s and the International Finance Corporation’s climate co-benefits reached record-high volumes in fiscal year 2022 after maintaining above-target values since fiscal year 2018.

The World Bank Group has regularized its surge in support for crises, conflicts, and fragility and moved toward greater prevention—issues that have taken on increased importance since the capital increase package was established.

This chapter covers the five clusters under the CIP’s second priority area—leading on global themes—namely, crisis and FCV, climate change, gender, knowledge and convening, and regional integration.

Crisis and Fragility, Conflict, and Violence

Crisis response is an important theme in both the Forward Look and the CIP. The CIP committed the Bank Group to continue strengthening its response to global and regional crises of all types, with a special emphasis on preventing FCV situations. Table 3.1 shows that the CIP had four FCV- and crisis-related commitments—one for IBRD, two for IFC, and one for both institutions. In summary, these commitments include the following: (i) IFC and the World Bank focusing more on conflict prevention; (ii) IBRD providing innovative financing solutions, such as its crisis buffer; (iii) IFC providing more upstream diagnostics and using de-risking financing tools, such as the PSW; and (iv) IFC improving its collaboration with the World Bank on FCV issues. The CIP monitored these commitments using two qualitative indicators with yes or no targets (table 3.1). These indicators focused on IBRD and IFC actions but did not capture their quality, effectiveness, and intended outcomes. The broad commitments and the few indicators on crisis response and FCV make it difficult to know what successful implementation of the CIP commitments was expected to look like for both institutions.

Crisis response became an even more dominant theme for the Bank Group than was called for in the CIP. The Forward Look and CIP objectives were defined with the expectation that the Bank Group would need to respond to occasional major crises, but the reality has turned out differently, with the Bank Group being forced to respond to several major and overlapping crises. As a result, the Bank Group has enhanced the way it prevents and responds to these events, as described in Navigating Multiple Crises, Staying the Course on Long-Term Development: The World Bank Group’s Response to the Crises Affecting Developing Countries and other reports (World Bank Group 2022c). The main takeaway from these documents is that as crises become more frequent and severe, there are increasing demands on the Bank Group to build resilience and respond to them.

Table 3.1. CIP Policy Measures for the World Bank Group for Crisis Management and Fragility, Conflict, and Violence

|

IBRD and IFC Policy Measures |

Commitments |

Indicators |

Targets |

|

Enhanced IBRD’s crisis response capacity incorporated in the Financial Sustainability Framework. |

Incorporate crisis response into IBRD Financial Sustainability Framework. CIP main text. Underlined and in annex summary of the capital package. |

Crisis buffer introduced. Annual approved amount of crisis buffer and resulting buffer-adjusted SALL level. |

Complete (yes/no). Monitored. |

|

IFC to strengthen partnerships with the World Bank and others to ensure a coordinated approach to crisis management and FCV. |

Strengthen IFC partnership with the World Bank and others to ensure a coordinated approach to crisis management and FCV. CIP main text. Underlined and in annex summary of the capital package. |

IFC’s FCS strategy integrated into World Bank Group FCV strategy. Reported in implementation updates narrative. |

Implemented (yes/no). |

|

Building on the Global Crisis Management Platform, the World Bank Group proposes to strengthen its efforts to support FCV situations, with a view to reinforcing country, regional and global stability, and development. Strong emphasis on crisis prevention. |

Strengthened response to national, regional, and global crises. Focus on preventing escalation of FCV situations and their spillover. CIP main text. Underlined and in annex summary of the capital package. |

No indicator in CIP implementation status table. Limited reporting in implementation updates narrative. |

No target. |

|

IFC’s upstream diagnostic work to guide its investments in high-risk FCV markets and implementation of specific de-risking solutions, such as PSW. |

Increasing IFC investments in high-risk FCV markets accompanied by upstream diagnostic work and implementation of specific de-risking solutions, such as PSW. CIP main text. Not underlined but listed in annex summary of the capital package. |

No indicator in CIP implementation status table. Limited reporting in implementation updates narrative. |

No target. |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The bold text in the table was underlined in the CIP document to show that these were formal commitments. CIP = capital increase package; FCS = fragile and conflict-affected situation; FCV = fragility, conflict, and violence; IBRD = International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; IFC = International Finance Corporation; PSW = Private Sector Window; SALL = sustainable annual lending limit.

Reporting

The Bank Group’s reporting on the FCV strategy stands out for its depth and candor of analysis. The importance of the Bank Group’s crisis and FCV agenda and the adoption of the FCV strategy in 2020 have meant that management has reported extensively on it. There have been regular Board updates on the Bank Group’s crisis responses, particularly its COVID-19 response and the FCV strategy’s implementation. The March 2022 Board update on the FCV strategy discussed the progress and challenges in addressing FCV issues and the limits to some of the Bank Group’s FCV response tools. For example, there is an increasing need for the Bank Group to engage on FCV issues in middle-income countries, but its response in these settings has been constrained by weak subnational capacity, limited concessional financing, and political hesitancy in some countries to involve the Bank Group in “domestic” conflicts, among other reasons (World Bank Group 2020b). The Bank Group’s narrative reporting on its FCV strategy addresses its specific CIP commitments, and, according to the validation team, it stands out among corporate reporting for its depth and candor, particularly on the challenges of operating and achieving results in FCV contexts. This reporting shows that high-quality reporting on qualitative commitments is feasible, although in this case it is driven by the FCV strategy more than by the CIP and its two yes-and-no indicators.

Implementation

IBRD and IFC have fully implemented their crisis and FCV commitments. IBRD’s first commitment was a specific action to incorporate a crisis response into its FSF. This has been achieved with IBRD’s crisis buffer allocation (described in chapter 5), which essentially sets aside IBRD funds for crisis lending. IBRD’s second FCV commitment included a broad set of actions to shift the Bank Group’s crisis work from response to prevention. The IFC commitments for this cluster were, first, to strengthen its partnerships and coordination on FCV approaches with the World Bank and other donors and, second, to increase IFC’s investments in high-risk FCV markets and accompany them with upstream diagnostic work and de-risking solutions. These commitments both require a broad set of actions that are not covered by any indicator. However, IFC has reported on these actions in its annual FCV strategy updates.

Crisis Response

The Bank Group provided a surge in financing for COVID-19 and other global and regional crises. This large financing response was enabled by the CIP, IBRD’s crisis buffer, the front-loading and early replenishment of IDA funds, and certain financial innovations, including new types of sustainable development bonds and IFC’s COVID-19 fast-track facility. These crisis responses were fast, flexible, at scale, globally coordinated, and tailored to the specific needs of recipient countries (World Bank 2022k). IFC’s early response—especially through the Financial Institutions Group—was mostly relevant to firms and in line with IFC’s expected countercyclical role (World Bank 2023b). The Bank Group’s COVID-19 response, in particular, assisted countries in addressing the pandemic’s health threats and social and economic impacts, while staying focused on the country’s long-term development goals (World Bank 2022k).

The Bank Group’s current approach to crisis response is built on its extensive experience responding to earlier crises and pandemics. IEG evaluations have pointed out many ways that the Bank Group has learned from past crisis interventions, including technical lessons in pandemic response, and the suitability of various financing instruments, such as the multiphase programmatic approach (World Bank 2022k). These evaluations also show that the Bank Group’s country-level crisis responses were more effective when they built on prior Bank Group engagements; for example, COVID-19 responses were more robust when they built on prior World Bank support for countries’ health and social protection systems (World Bank 2022k). In many countries, World Bank–supported social protection programs adjusted to the crises by scaling up and adding crisis response mechanisms. Another IEG evaluation found that the Bank Group was less effective in working with clients to expand fiscal buffers, strengthen institutions, and build capacity for better management of fiscal and financial crises (World Bank 2021a).

The Bank Group has begun taking a longer-term perspective to pandemic preparedness, although its efforts in this area have waxed and waned over the years. The 2014–15 Ebola outbreak led to the Bank Group’s renewed focus on pandemics. The Forward Look emphasized pandemic preparedness, the CIP less so. However, COVID-19 led the Bank Group to increase its focus on pandemics. As part of its response, the World Bank strengthened public health preparedness and built resilience in health, education, and social protection systems. The Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility (PEF), launched by the Bank Group in 2016 (largely in response to the Ebola outbreak), played a modest role in the pandemic response. PEF grants supported countries’ COVID-19 plans, but the grant amounts were small, and the allocation of just-in-time PEF resources was slow. This was because the PEF required that an emergency be declared before World Bank teams could access funding, and this funding had to be included in a World Bank financing project in order for recipient governments to use it. The Bank Group also started to take a longer-term view of pandemic preparedness. The international community has a long history of calling for increased investments in crisis preparedness after major disasters and pandemics only to see the funding and political commitment fade after the crisis’ immediate urgency passes (World Bank 2013). To help address this cycle of neglect, the Bank Group created the Financial Intermediary Fund for Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness, and Response in 2022. The fund has so far received $1.4 billion in capital commitments, against an estimated annual need of $10.5 billion for a fit-for-purpose pandemic preparedness and response architecture (WHO and World Bank 2022; World Bank 2022d).

Fragility, Conflict, and Violence

The Bank Group has strengthened its approach to FCV challenges. It adopted the FCV strategy (2020–25), introduced a new operational policy, and increased FCV funding, primarily through IDA’s FCV envelope. In addition, the Bank Group strengthened its partnerships with the United Nations and humanitarian agencies to coordinate responses to the humanitarian and development needs of conflict-affected countries. The World Bank has also improved its conflict and fragility analytics to help meet its commitment to greater conflict prevention, and it has revised its methodology for conflict analysis, which included making Risk and Resilience Assessments a “core diagnostic.” A recent IEG evaluation found that the Bank Group’s conflict analyses have become better at identifying fragility drivers and their influence on conflict and violence. This evaluation also found that World Bank investment projects in conflict-affected areas increasingly address conflict and fragility drivers but that the World Bank could do more to inform country engagements with timely analyses on conflict dynamics and risks (World Bank 2021c).

The PSW has helped IFC enter new markets and sectors, but it has been challenging for IFC to increase investments in FCV because of the risks, complexities, and informality of FCV environments. Taking the longer perspective over the FY10–21 period, IFC’s long-term financing commitments to FCS have been relatively flat (averaging 5.2 percent of its total commitment volume and 8.6 percent of its total number of committed projects), despite IFC introducing or adapting a suite of instruments partly to target FCS, including upstream advisory services, blended finance, and country diagnostics. IDA’s PSW is IFC’s largest blended finance program and was designed to mobilize private sector investment in IDA-only and IDA FCS countries through de-risking at both the country and transaction levels. Although IFC’s business volume in PSW-eligible countries did not increase during the 18th Replenishment of IDA, the PSW has helped IFC enter new markets and sectors. More generally, nonconducive business environments and the shortage of potentially bankable projects, or projects that meet IFC standards and criteria, are constraining its attempts to scale up its business in FCS, more than the lack of available finance. IFC has responded to the shortage of bankable projects by investing in upstream project development and pursuing blended finance, among other responses (World Bank 2022c).

The World Bank and IFC face both internal and external challenges in supporting FCS that are unique to those situations. Research shows that most jobs and economic opportunities in FCS, particularly for the disadvantaged, are in the informal sector, but the Bank Group has few instruments for working directly with the informal sector. FCS rarely have conducive business environments and project sponsors with relevant experience. Moreover, loans are typically small, and transaction costs are high in FCS. It can also be hard to attract staff to these locations. For IFC, scaling up in FCS would require further adjustments to its risk tolerance, cost structure, institutional incentives, and willingness to experiment and pilot new approaches and instruments. It would also require greater collaboration with the World Bank (World Bank 2022c).

Climate Change

The climate change cluster has specific measurable commitments and is aligned with other corporate strategy documents. This cluster’s six commitments focus on integrating climate considerations in operations and country strategies (table 3.2). The commitments, which the CIP monitored with one qualitative and four quantitative indicators, are aligned with the Bank Group’s 2016 Climate Change Action Plan (World Bank Group 2016a), IDA’s climate change commitments, and the Forward Look’s climate objectives. Moreover, the CIP expands the Forward Look’s climate ambitions by increasing the Forward Look’s climate co-benefit targets and expanding its focus on private sector solutions and global climate advocacy. Bank Group management has consistently reported on all CIP climate change commitments, using the agreed-on corporate indicators, most of which are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound. However, they focus on the Bank Group’s lending and do not do justice to the breadth of the Bank Group’s nonlending work on climate action. Moreover, the co-benefits accounting methodology, which is a joint multilateral development bank (MDB) methodology, has limitations, such as not capturing the intended outcomes, only capturing projects’ ex ante intentions, and combining investment and development policy operations’ co-benefits in a single metric despite underlying differences.1

Table 3.2. CIP Climate Change Policy Measures for IBRD and IFC

|

Policy Measures |

Commitments |

Indicators |

Targets |

|

For IBRD, the package will support increasing the climate co-benefit target of 28% by FY20 to an average of at least 30% over FY20–23, with this ambition maintained or increasing to FY30. |

IBRD average climate co-benefits of at least 30% over FY20–23, with this ambition maintained or increasing to FY30, reaching a cumulative $105 billion, 1.8 times or $45 billion more than if no package. CIP main text. Underlined and in annex summary of the capital package. |

Share of climate co-benefits in total commitments (%). |

At least 30% average over FY20–23. Ambition maintained or higher in FY24–30. |

|

All IBRD-IFC projects will be screened for climate risk. |

All projects screened for climate risk. CIP main text. Underlined and in annex summary of the capital package. |

IBRD: Annual percent of operations screened for climate risk. IFC: Annual percent of projects screened for climate risk within the sectors where climate risk screening was mainstreamed. |

100%. |

|

IBRD-IFC investment operations in key emission-producing sectors will incorporate the shadow price of carbon in economic analysis and apply GHG accounting, with annual disclosure of GHG emissions. |

IBRD-IFC investment operations in key emission-producing sectors to incorporate the shadow price of carbon in economic analysis and to apply GHG accounting, with annual disclosure of GHG emissions. CIP main text. Underlined and in annex summary of the capital package. |

IBRD: Annual percent of operations screened for climate risk. Annual disclosure of related GHG emissions. IFC: Annual percent of eligible projects incorporating shadow carbon pricing. Annual percent of eligible projects applying GHG accounting and disclosure. |

100%. Implemented (yes/no). 100% by FY20. 100% by FY20. |

|

In cooperation with other MDBs, the World Bank Group will review the methodology used for computing climate co-benefits with a view to better capturing adaptation benefits. |

In cooperation with other MDBs, the Bank Group will review the methodology used for computing climate co-benefits with a view to better capturing adaptation benefits. CIP main text. Underlined and in annex summary of the capital package. |

Progress in reviewing and improving methodology for computing climate co-benefits to improve capturing of adaptation benefits. |

Complete (yes/no). |

|

IFC will increase climate investments, including mitigation and adaptation projects, to 35% of commitments by 2030. Over FY19–30, the average would be 32%. |

Increasing share of climate investments to 35% by FY30 and reaching an average of 32% between FY20 and FY30 compared with 28% in the no-capital increase scenario. CIP main text. Underlined and in annex summary of the capital package. |

Share of climate investments as a percent of LTF own-account commitments. |

35% by FY30. 32% average in FY20–30. |

|

IFC will leverage World Bank policy work (under the Cascade approach) and expand the use of private sector solutions that cut across sectors and country groups. |

IFC will leverage World Bank policy work and expand use of private sector solutions that cut across sectors and country groups, expand share of early-stage equity investments and new technologies, and help countries meet their NDCs. CIP main text. Underlined and in annex summary of the capital package. |

No indicator in CIP implementation status table. Limited reporting in implementation updates narrative. |

No target. |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The bold text in the table was underlined in the CIP document to show that these were formal commitments. CIP = capital increase package; FY = fiscal year; GHG = greenhouse gas; IBRD = International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; IFC = International Finance Corporation; LTF = long-term financing; MDB = multilateral development bank; NDC = nationally determined contribution.

Implementation

Bank Group management has fully implemented the climate change commitments. It put internal climate commitment tracking tools in place, including climate risk screening, greenhouse gas accounting, co-benefit tracking, and adapted information technology systems, and provided guidance and training to staff on complying with these commitments. All 18 country engagement documents reviewed for this validation prioritize climate action; 12 of them strongly link those actions to the country’s nationally determined contributions and national climate change strategies, and 15 include private sector solutions in the proposed work programs. The CIP’s focus on engaging the private sector in climate action has also been reflected in the Bank Group’s commitments under the Climate Change Action Plan 2021–25, and in its sector- and country-level climate strategies.

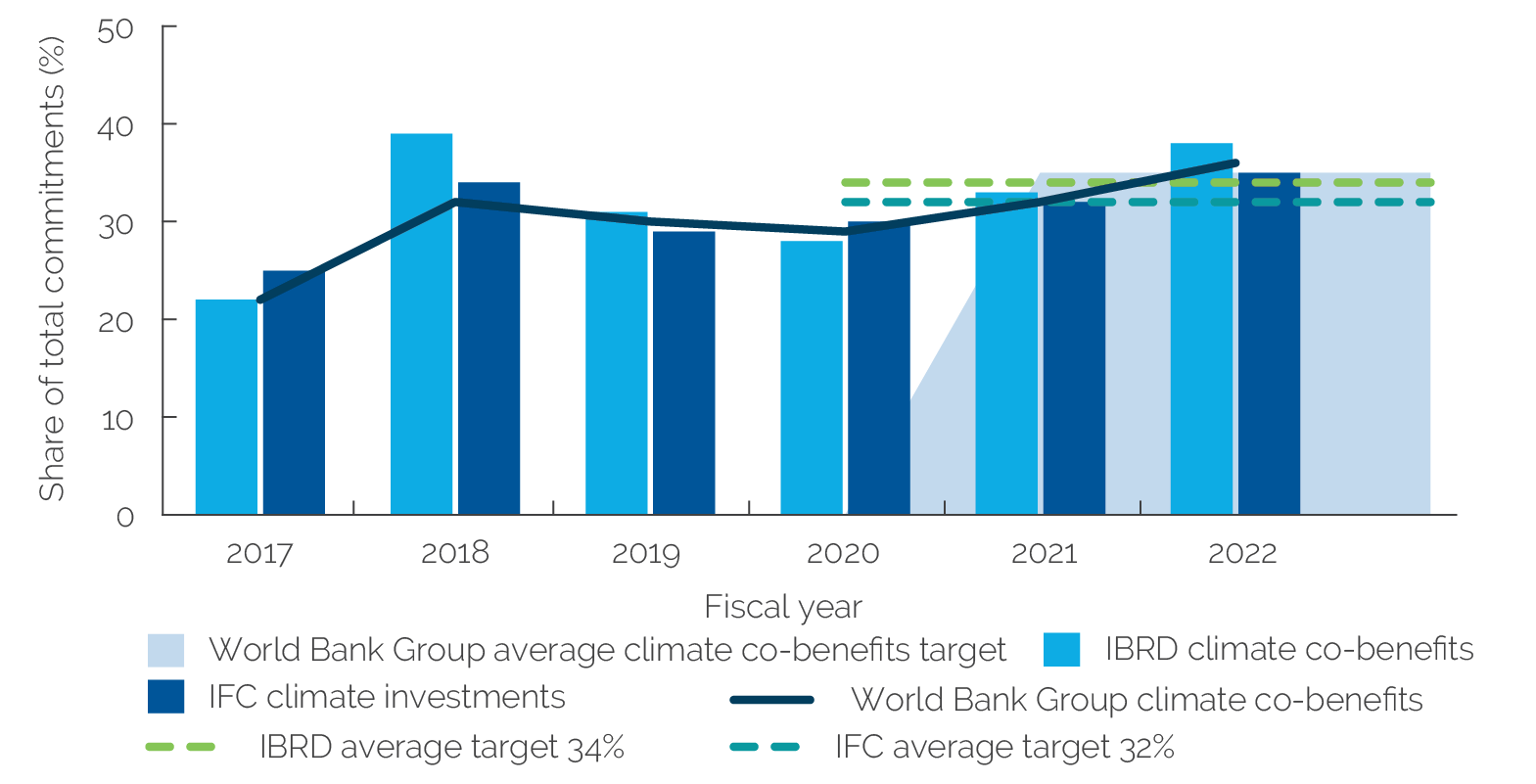

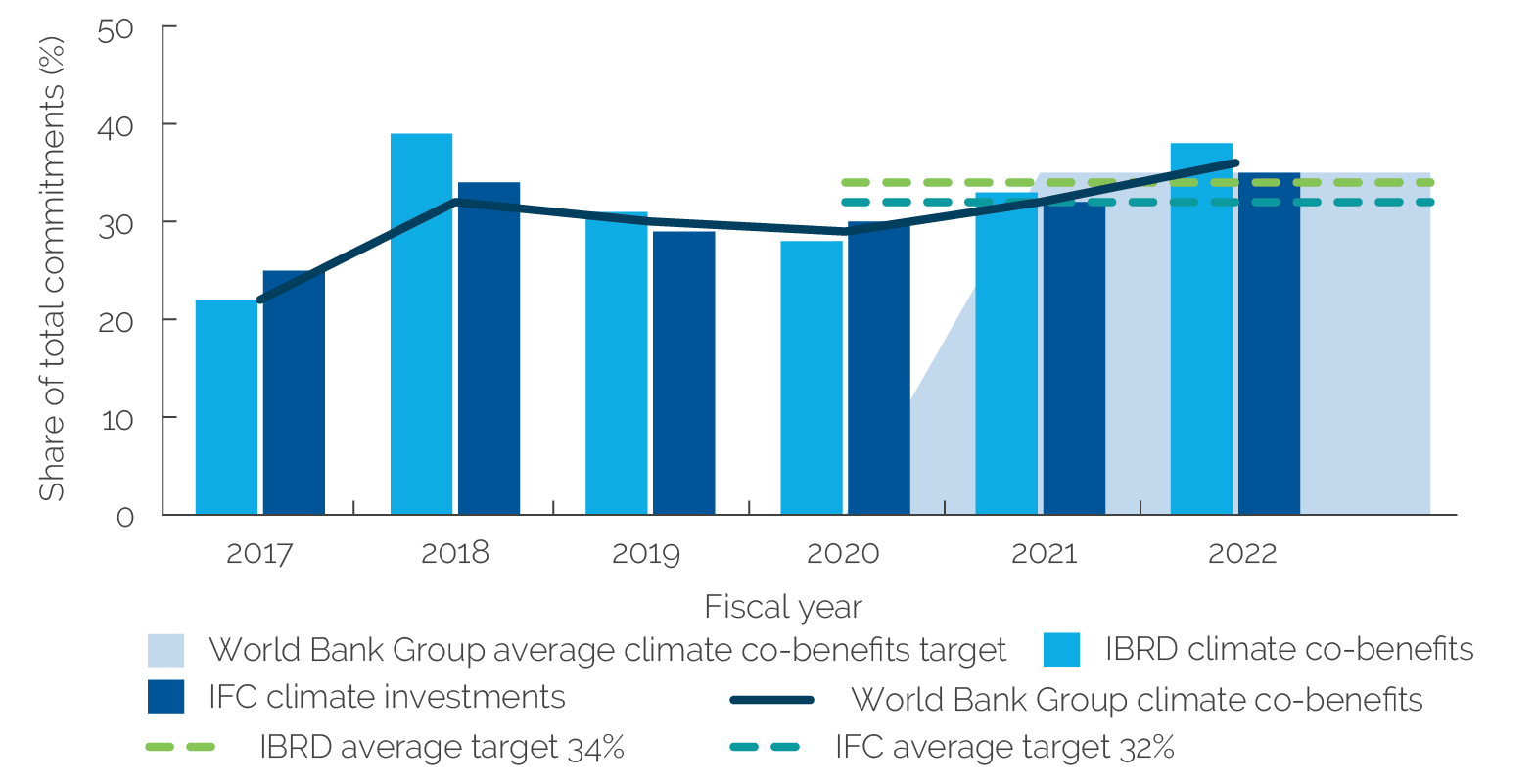

IBRD and IFC met or exceeded all of the CIP’s quantitative climate change targets. The share of climate lending and investments averaged 34 percent against a minimum target of 30 percent for IBRD and averaged 32 percent against a target of 32 percent for IFC over the FY20–22 period (figure 3.1). The shares of IBRD and IFC co-benefits in total commitments reached an average of 36 percent in FY22 and have remained above the Bank Group’s CSC target of 35 percent set for the FY21–25 period. IBRD and IFC screen all investment operations in the most greenhouse gas emissions-intensive sectors for climate risk, incorporate carbon shadow prices into their economic analyses, undertake greenhouse gas accounting, and disclose investments’ contribution to greenhouse gas emissions reductions. Moreover, the Bank Group has scaled up its climate change analytics through its Country Climate and Development Reports and other tools.

Figure 3.1. World Bank Group Climate Finance

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The World Bank Group Climate Change Action Plan target is to average 35 percent of the World Bank Group’s financing to have climate co-benefits over fiscal years 2021–25. IBRD = International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; IFC = International Finance Corporation.

Climate indicators and the systems that track them have created incentives for operational teams to expand their projects’ climate change components. Corporate indicators and targets, such as those committed to in the CIP, have acted as internal measures that hold business units accountable for achieving specific climate outputs. As such, these indicators have cascaded through results agreements, incentivizing management and project teams to maximize climate co-benefit volumes in their portfolios and projects.

The Bank Group is boosting its adaptation efforts and enhancing some climate result measurement methodologies. The Bank Group collaborates with other MDBs on a harmonized climate co-benefits methodology, thereby achieving a CIP commitment. For mitigation co-benefits, the task redefined the activities that qualified as co-benefits based on sector and subsector taxonomies. For adaptation, the Bank Group developed a climate resilience rating system to complement its climate co-benefit methodology, which provides guidance to teams on developing climate-resilient projects and measuring the project’s ability to withstand natural disasters and climate change impacts and build resilience among beneficiaries (World Bank 2021b). In addition, the World Bank Group’s Action Plan on Climate Change Adaptation and Resilience set an adaptation financing target for the World Bank of $50 billion over the FY21–25 period, which is more than double the levels from the FY15–18 period (World Bank Group 2019b).2 In FY22, the World Bank’s CSC started monitoring the share of adaptation co-benefits within total climate co-benefits, aiming for at least a 50 percent share.

The Bank Group’s corporate climate change indicators, such as those used in the CIP, do not assess higher-level climate outcomes. These indicators have many strengths, including being attributable, specific, measurable, achievable, and relevant. Moreover, the Bank Group’s climate co-benefit indicator has embedded climate considerations into Bank Group operations. However, like many other corporate results indicators, it measures inputs and processes rather than outcomes. Specifically, the climate co-benefit indicator estimates the dollar amount that the Bank Group commits to activities with potential climate change benefits. It does not measure whether funds were disbursed, nor if outputs resulted in actual climate change benefits, such as avoided emissions or increased resilience. In other words, the co-benefit indicator measures the breadth of the Bank Group’s climate action rather than its depth, which reinforces a staff incentive to comply with commitments instead of achieving greater development impact. At the project level, climate-related indicators complement the climate co-benefit indicator. Since FY21, projects with climate finance of 20 percent or higher include a climate-related indicator to track the achievement of results over the project cycle. An IEG learning engagement showed that these indicators contain a lot of useful evidence on achieving climate change results and, with some improvements, could be used to improve corporate reporting on climate change (World Bank 2022g). Conversely, a recent IEG evaluability assessment of IFC’s climate change monitoring identified important limitations that prevent IFC from transitioning to more outcome-oriented indicators. These limitations include IFC’s weak tracking of climate change savings during project implementation or closure and the limited provision of climate change-related data from clients (World Bank 2022b).

IFC has led on innovative climate solutions. It is diversifying its portfolio beyond renewables to include investments in climate-smart cities and blue finance (including blue bonds and loans for protecting clean water resources). IFC is playing a leadership role among clients, partners, and financial institutions to develop a global blue economy finance market. In 2022, IFC developed global guidelines for blue bond lending and issuances. In emerging markets, IFC is also increasing sustainability-linked financing, such as investments in so-called super green structures—that is, sustainability-linked instruments that companies commit to using the proceeds from to fund green or social projects (IFC 2022c). IFC has successfully promoted green buildings through its Excellence in Design for Greater Efficiencies certification and standards process to advance energy efficiency priorities across market segments (World Bank 2023c).

IEG’s climate-related evaluations have found that the Bank Group’s climate change efforts are yielding positive results despite some common challenges. An IEG evaluation found that the Bank Group’s convening on climate issues was in high demand and often successful (World Bank 2020c). This validation’s synthesis of three IEG evaluations and one Evaluation Insight Note conducted after 2018 (World Bank 2018, 2022f, 2022h, 2022i) find that the Bank Group has consistently expanded its climate support, achieved ambitious targets, built country capacities to act on climate change, and provided proof of concept for innovative approaches. These evaluations also identified three common shortcomings in the Bank Group’s climate support—namely, (i) challenges in sustaining outcomes. For example, evaluations noted challenges to the financial sustainability of municipal solid waste management projects (World Bank 2022h), and to disaster risk reduction projects which did not always ensure the necessary maintenance of infrastructure (World Bank 2022f); (ii) challenges in continuously updating staff’s specialized technical climate skills because the needs keep evolving, as in, for example, when the adoption of nature-based solutions for disaster risk reduction became limited by perceptions that they are too complex because they require many staff specializations (World Bank 2022f); and (iii) weak internal collaboration, which leads to a fragmented approach. For example, an evaluation in 2018 found that, at the time, coordination and collaboration between IBRD and IFC on carbon finance was limited (World Bank 2018). In a notable exception, IFC’s climate team fostered excellent collaboration across industry groups on energy efficiency (World Bank 2023c).

Gender

The gender cluster’s CIP policy measures and commitments were aligned with the Bank Group’s gender strategy. IBRD and IFC’s CIP gender commitments, indicators, and targets came directly from the Bank Group’s gender strategy, and all six commitments had quantitative indicators and targets, which facilitated reporting (tables 3.3 and 3.4). The CIP’s gender indicators relied on the flag-and-tag methodology, which only captures projects’ intent at design. They do not capture the quality, effectiveness, or outcomes of the Bank Group’s interventions. The IBRD indicators provide incentives to focus on individual projects instead of encouraging a country-driven approach to addressing gender gaps. As we will see later in this section, IBRD has fully implemented its two CIP gender commitments and exceeded its targets for these. Likewise, IFC has fully implemented its four gender commitments and has a well-organized approach to implementing the gender strategy.

Table 3.3. CIP IBRD Gender Policy Measures

|

IBRD Policy Measures |

Commitments |

Indicators |

Targets |

|

Continuous implementation of the gender action plan, with at least 55% of IBRD operations contributing to narrowing the gender gap by FY23. |

Increase the proportion of IBRD operations that narrow gender gaps (“gender tagged”). CIP main text. Underlined and in annex summary of the capital package. |

Percent of operations that are gender tagged. |

55% by FY23 with ambition maintained or increasing to FY30. |

|

60% of operations with financial sector components narrowing gaps in access to financial services by FY23, with this ambition maintained or increasing to FY30. |

Increase in the share of IBRD operations with financial sector components that include specific actions to close gender gaps in access to and use of financial services. CIP main text. Underlined and in annex summary of the capital package. |

Percent of operations with financial sector components that include specific actions to close gender gaps in access to and use of financial services. |

60% by FY23 with ambition maintained or increasing to FY30. |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The bold text in the table was underlined in the CIP document to show that these were formal commitments. CIP = capital increase package; FY = fiscal year; IBRD = International Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

Table 3.4. CIP IFC Gender Policy Measures

|

IFC Policy Measures |

Commitments |

Indicators |

Targets |

|

IFC will quadruple the amount of annual financing dedicated to women and women-led SMEs by 2030. |

IFC aims to quadruple the amount of annual financing dedicated to women and women-led SMEs. CIP main text. Underlined and in annex summary of the capital package. |

Amount of annual financing dedicated to women and women-led SMEs. |

$1.4 billion per year by FY30. |

|

Increase the amount of annual commitments to financial intermediaries specifically targeting women. |

$2.6 billion in annual commitments to financial institutions specifically targeting women by 2030. CIP main text. Underlined and in annex summary of the capital package. |

Amount of money committed to financial institutions targeting women. |

$2.6 billion by FY30. |

|

IFC will also flag all projects with gender components by 2020. |

Flagging all projects with gender component by 2020. CIP main text. Not underlined but listed in annex summary of the capital package. |

All projects with gender component flagged as applicable. |

100%. |

|

IFC aims to double the share of women directors that IFC nominates to boards of companies where it has an equity investment. |

Doubling the share of women directors IFC nominates to boards of companies where it has an equity investment (from 26% currently to 50%). CIP main text. Not underlined but listed in annex summary of the capital package. |

Percent of women directors IFC nominates to boards. |

50% of women directors by FY30 (increase from 26% baseline). |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The bold text in the table was underlined in the CIP document to show that these were formal commitments. CIP = capital increase package; FY = fiscal year; IFC = International Finance Corporation; SME = small and medium enterprise.

Reporting

IBRD’s and IFC’s reporting on their CIP gender implementation has been mostly adequate. Reporting was aligned with gender strategy reporting and facilitated by existing corporate metrics on gender. IBRD has two well-defined CIP indicators that focus on improving gender project designs, but they do not capture the full scope or richness of the World Bank’s gender work. Annual CIP updates also contain meaningful descriptions of the Bank Group gender strategy’s implementation, including the use of gender action plans by Regions and Global Practices. IFC’s CIP reporting framework adequately covers its four CIP gender commitments, using indicators that monitor the breadth of its actions. However, IFC’s CIP targets for three of its four CIP gender commitments are set for 2030—a distant result—whereas CSC sets annual targets and their achievements for some of the commitments.

Implementation

World Bank and IFC staff, management, and partners have demonstrated their commitment to the Bank Group’s gender strategy—a precondition for its success. IEG’s Mid-Term Review of the gender strategy found that it, along with its gender flag-and-tag approach, which defines a logical process for addressing a gender gap with actions, analyses, and indicators for each project, has generated attention and accountability. Specifically, the gender flag-and-tag and associated targets increased staff attention to gender issues, fostered accountability, and led to improvements in project design. The Mid-Term Review also found that IFC and the World Bank have collaborated well on implementing the gender strategy. The review of the strategy by GIA echoed the Mid-Term Review’s findings stating that management created incentives to ensure that processes reinforce the strategy’s aims (GIA 2020). IBRD has exceeded its target of having 55 percent of its project designs close gender gaps, reaching 90 percent of all of its operations approved in FY22. Likewise, in FY22, IBRD exceeded its target of having 60 percent of IBRD project designs with financial sector components closing gender gaps in access to finance, reaching 63 percent (World Bank Group 2022a). Moreover, IBRD also made progress in developing and updating gender action plans, conducting country diagnostics, and integrating these into country plans. The close monitoring of indicators and targets has incentivized frontline units to prioritize gender issues, develop their own gender action plans, appoint gender focal points to advise operational teams, organize trainings and communities of practice, establish a knowledge repository, develop a competency framework for gender experts, and create a career path for gender experts (World Bank 2021d). IEG’s Mid-Term Review also highlighted IFC’s well-organized internal coordination for closing gender gaps and implementing the strategy. IFC created gender leads and focal points. Its Gender Business Group works through regional and product gender leads and coordinates with focal points in industry groups. These coordination efforts have created effective links between country-level advisory services and global programs, such as the Women’s Insurance and Tackling Childcare projects (World Bank 2021d).

There were also areas where implementation of the gender strategy could have been more comprehensive. The Gender Group and other units have improved data and evidence. However, the implementation of the gender strategy was affected by the general lack of familiarity with the gender gap approach among staff, and competing requirements to integrate many other cross-cutting priorities into operational practices. Not all Regions and Global Practices were able to provide their staff with well-organized support from gender specialists to overcome these shortcomings. Similarly, the World Bank’s COVID-19 response lacked hands-on assistance from gender specialists and did not pay enough attention to supporting gender equality (World Bank 2022k). Moreover, the gender strategy proposed a country-driven approach to narrowing gender gaps through multiple instruments acting in concert; however, in practice, implementation often took the form of stand-alone projects. IEG’s Mid-Term Review of the gender strategy concluded that Bank Group management could address these concerns by letting teams from different Regions, Global Practices, and industry groups jointly develop country gender portfolios with greater synergies, promote knowledge generation to inform country gender priorities, improve the gender capacity of staff working on gender issues, and consider new corporate gender indicators that could better assess gender outcomes and support timely course corrections (World Bank 2021d).

The World Bank’s and IFC’s flag-and-tag approach to tracking gender commitments has had unintended effects on staff incentives. More specifically, this approach incentivizes teams and managers to focus on completing the tag and achieving the target indicator rather than pursuing a higher-level outcome. As a result, in some cases, project staff adjusted projects to the minimum level necessary to satisfy these indicator commitments. Likewise, the gender flagging tracks project design intentions regarding gender, but it does not adequately monitor and evaluate projects’ and country engagements’ implementation and outcomes (World Bank 2021d).

Knowledge and Convening

The CIP’s knowledge and convening cluster contained six policy measures. This included two policy measures for the Bank Group, two for IBRD, and two policy measures for IFC (table 3.5), which the CIP monitored with two qualitative indicators, but no targets. This cluster’s intended outcome was for the Bank Group to improve its knowledge and convening power to address global issues, but the policy measures were not clearly defined, and its indicators did not capture the quality or effectiveness of the World Bank’s efforts in this area. IEG could not validate the degree to which the Bank Group has achieved this because of the cluster’s lack of specificity and some reporting shortfalls. More specifically, the Bank Group does not monitor the uptake, quality, and relevance of its knowledge products nor the quantity and outcomes of its convening activities. Indeed, these things are not easy to monitor, but the absence of monitoring reduces the Bank Group’s accountability for delivering results in these strategically important areas.

Table 3.5. World Bank Group’s CIP Policy Measures for Knowledge and Convening

|

World Bank Group Policy Measures for Knowledge and Convening |

Commitments |

Indicators |

Targets |

|

The World Bank Group—Leveraging Bank Group knowledge and convening role for greater impact, including demonstration effects of implementing the Cascade approach. |

CIP main text. Not underlined but listed in annex summary of the capital package. |

No indicator in CIP implementation status table. Limited reporting in implementation updates narrative. |

No target. |

|

The Bank Group—Convening the public and private sectors on pressing global challenges. |

CIP main text. Not underlined but listed in annex summary of the capital package. |

No indicator in CIP implementation status table. Limited reporting in implementation updates narrative. |

No target. |

|

The World Bank will develop SFK generation and sharing to preserve and enhance its comparative advantage in this area. World Bank Group efforts will focus on sharing new research to underpin improved policy-making on emerging challenges; systematically harnessing and sharing knowledge (for example, South-South exchange) embedded in financing operations across the income spectrum; supporting innovative approaches for data collection; and continuing to strengthen public access to development data. |

Develop SFK generation and sharing. CIP main text. Underlined and in annex summary of the capital package. |

SFK generation and sharing developed and presented to the Board. |

Complete (yes/no). |

|

Dedicate part of IBRD income to provide concessional financing GPG. |

Establish an IBRD fund that uses IBRD surplus income to provide concessional financing for GPG. CIP main text. Not underlined but listed in annex summary of the capital package. |

Annual amount of funding dedicated to GPG fund from IBRD surplus. |

Implemented (yes/no). Monitored (no target). |

|

IFC will focus on critical mentoring and financial infrastructure to support entrepreneurship and innovation. |

CIP main text. Not underlined and not listed in annex summary of the capital package. |

No indicator in CIP implementation status table. Not reported. |

No target. |

|

IFC will invest with players that have the potential to become regional champions and facilitate transfer of new technologies to solve development issues. To scale up in this area, IFC will work more closely with the World Bank to advise and support policy improvements. |

IFC to also invest with private companies that have the strategy and the potential to become regional champions. CIP main text. Not underlined but listed in annex summary of the capital package. |

No indicator in CIP implementation status table. Limited reporting in implementation updates narrative. |

No target. |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The bold text in the table was underlined in the CIP document to show that these were formal commitments. CIP = capital increase package; GPG = global public good; IBRD = International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; IFC = International Finance Corporation; SFK = Strategic Framework for Knowledge.

Reporting

IBRD and IFC have only partially reported their actions on knowledge and convening, which hampered IEG’s validation of this cluster’s results. Actions include IBRD’s introduction of the Strategic Framework for Knowledge (SFK) and both institutions’ efforts to focus knowledge products on core diagnostics, such as the Bank Group’s Country Climate and Development Reports and IFC’s Country Private Sector Diagnostics (CPSDs). However, CIP reporting has not covered some of the less specific policy measures in this cluster. For example, it is unclear to what extent IFC implemented the CIP policy measure to invest in companies with the potential to become “regional champions,” which refers to companies that invest in one country then expand into another emerging market. It is also unclear to what extent the Bank Group helped countries share their experiences implementing the Cascade approach and Maximizing Finance for Development (MFD).3 The Bank Group’s lack of explicit commitments made progress difficult to judge. In addition, the lack of indicators, internal databases, and results systems on knowledge and convening hampers reporting and the understanding of outcomes in this cluster.

Implementation

IBRD has implemented its policy measures in the knowledge and convening cluster, although their results are difficult to independently validate. IBRD created the SFK (discussed in this chapter), widely shares its data and research with the public, and set up the global public goods fund to provide concessional finance for global public goods in middle-income countries. It also provided an initial $85 million in surplus funds to this fund as capital, although it was clear that this would not be enough over the fund’s life. As the CIP document states, there should be “up to $45 million per year for potential income support for [global public goods] projects” (38). The original CIP document does not define the fund’s duration nor the amount or frequency of IBRD’s annual surplus transfers. The fund continues to operate, and the provision of concessional resources for global public goods and the role of the fund is a major theme in discussions about the Bank Group’s evolution. The results of this cluster’s other commitments were also hard to validate, including commitments for convening, knowledge sharing, and data innovation. However, although these areas did not have indicators or targets in the CIP, the Bank Group still focused on them and launched several high-profile and innovative initiatives, including on COVID-19 crisis monitoring.

Knowledge

The World Bank has developed various approaches to managing knowledge since the mid-1990s. It introduced the “Knowledge Bank” concept in 1996 to systematically make its knowledge available to anyone who wanted it. The World Bank then created sector networks in 1997; developed the knowledge strategy in 2010 (World Bank 2010); underwent organizational reforms in 2014 (which created Global Practices to strengthen global knowledge flows); in 2017 developed a Knowledge Management Action Plan and a central knowledge management team led by a director (now disbanded); and realigned staff reporting lines from Global Practices to Regions in 2019 and 2020 to ensure that global knowledge is serving country programs (World Bank Group 2021e).

The SFK captures the Bank Group’s current approach to knowledge management (World Bank Group 2021e). Its diagnostics are built on IEG’s evaluation research and other Bank Group evidence on knowledge and identified ways for the Bank Group to strengthen its knowledge management. The SFK took a broad-brush approach to the question of how to manage the Bank Group’s knowledge. It raised critical questions with unknown or contested answers, including questions on how to measure knowledge and formalize tacit knowledge, but it did not include an action plan. It is too early to assess the SFK’s success, but the Bank Group’s Board of Executive Directors has expressed doubts about its effectiveness in strengthening knowledge. On a related note, IEG has begun evaluating the knowledge embedded in financing operations—a key part of the SFK.

The Bank Group has started identifying knowledge gaps in its country engagement products. This assessment reviewed 18 country engagement products that have been issued since July 2021. The review shows that most of the documents identify knowledge gaps, but only 5 out of 18 do so in a systematic way by linking the gaps to the CPF’s proposed objectives and work areas. One of these 5 was the Uzbekistan CPF for FY22–26 because it identified knowledge gaps for each CPF objective and established clear links to the planned country program.

Convening

The Bank Group has strong convening power on global and regional issues. Effective convening is about engaging partners to drive collective action from many actors. IEG evaluations find that the Bank Group’s knowledge, global reach, and ability to link global issues with action in country programs make it a sought-after convenor on many international development topics (World Bank 2020c).

The Bank Group can enhance its convening outcomes by focusing more intentionally and selectively on those topics where it has strong capacity. According to IEG’s convening evaluation, the Bank Group tends to be a more effective convenor when the convening issue aligns with the Bank Group’s core goals and mandates and is embedded in select country programs. Other factors that sustain convening over the longer term include adequate resources, established expertise and experience, and data and knowledge work that can inform and persuade partners. The Bank Group does not have the capacity to provide strong and sustained leadership on all the topics where the international community seeks its engagement. However, corporate strategy documents do not provide clear guidance on this—they do not have a defined set of issues in which the Bank Group is well placed to convene around nor address how convening efforts link with the Bank Group’s country-driven model. When Bank Group convening has been unsuccessful, it has often been because convening efforts were spread too thin or because internal or external consensus on an approach to the topic was missing.

Regional Integration

Reporting

The regional integration cluster has a single, broad policy measure (table 3.6). Stated simply, this cluster’s goal is to integrate countries through connective infrastructure and complementary policies and institutional reforms. As a result, it largely focuses on improving cross-border energy and transportation, and information and communication technologies infrastructure. The indicator used by the CIP to monitor this cluster’s commitment was unclear, not measurable, and limited to World Bank actions and not its intended outcomes. The CIP did not set targets for this cluster, and its reporting has been qualitative, describing the World Bank’s Africa regional integration lending portfolio; offering examples of technical assistance and advisory services, often on trade; and describing IFC and MIGA’s financing, upstream work, and advisory services. This reporting gives an idea of what types of regional integration activities the Bank Group pursues but does not provide much detail on the depth or scope of this work nor on its results.

Table 3.6. World Bank Group’s CIP Policy Measures for Regional Integration

|

World Bank Group Policy Measures for Regional Integration |

Commitments |

Indicators |

Targets |

|

The World Bank Group will continue to work with regional entities, other development partners, and the private sector to help build the connective infrastructure in areas such as transport, information and communication technologies, and energy. The Bank Group will support efforts on complementary policy and institutional reforms that are needed to ensure that gains from regional cooperation on infrastructure materialize fully, to foster growth of businesses and create good local jobs and value addition in all participating countries in an inclusive and sustainable manner. |

Supporting inclusive and sustainable regional integration through connective infrastructure and complementary policy and institutional reforms. CIP main text. Not underlined and not listed in annex summary of the capital package but recognized as commitment in implementation status table. |

IBRD—Progress in supporting regional integration through projects and advisory services and analytics. Reported in CIP implementation status table and implementation updates narrative. |

No target. |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: CIP = capital increase package; IBRD = International Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

Implementation

The World Bank has expanded and broadened its regional integration support. More specifically, it has expanded its focus beyond Africa—the Region where it has most actively and effectively fostered regional integration (World Bank 2019b). The World Bank has also expanded beyond its traditional focus on trade and infrastructure. For example, IDA’s CIP commitments address transboundary drivers of fragility and strengthen its regional crisis risk preparedness. IDA has also increased funding for the Regional Window of the 20th Replenishment of IDA to support regional projects. The World Bank’s two Sub-Saharan Africa Regions and its Middle East and North Africa Region jointly presented a regional integration strategy update to the Board in 2021. This update expanded the strategy’s focus on addressing fragility risks in Africa’s various subregions. In South Asia, the World Bank refocused its regional integration, cooperation, and engagement approach. It has also increased its engagement with regional organizations. For example, the World Bank’s COVID-19 response supported and collaborated with regional organizations, including the African Union and the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (World Bank 2022k). It also worked with the African Union to implement the African Continental Free Trade Area and identify trade benefits for the African Union’s trade negotiations with individual governments (World Bank Group 2021f). The World Bank has also continued to support transport and trade connectivity through diagnostics and technical assistance in South-East Asia, Latin America, the Horn of Africa, and the Africa Continental Free Trade Area (World Bank Group 2022a).

The World Bank has internal and external constraints preventing it from deepening its support for regional integration: its systems, accountability mechanisms, and incentive structures follow the country-driven model and are therefore oriented toward individual countries and not well geared for engaging across countries (World Bank 2019b). The World Bank addresses such constraints by adopting regional integration strategies and appointing regional directors to implement them, mirroring the way that country directors oversee country engagements. However, it has not clarified exactly what success on regional integration looks like. There are also external constraints. For example, regional integration projects are harder to design and implement because they require external collaboration, regional champions, and strong implementation capacity among all the involved countries.

- The assignment of climate co-benefits to development policy operations is problematic, although it is based on a joint multilateral development bank methodology. Because the financing provided by a development policy operation does not go to finance the reforms supported by a prior action, there is a qualitative difference in assigning a value to the climate co-benefits of a development policy operation as compared with assigning a value to an investment project. Whereas investment projects in principle have a link from the amount of financing to the supported climate actions, that is not the case for development policy operations.

- The International Finance Corporation does not have a volume or percentage target for adaptation finance.

- Both the Cascade approach and Maximizing Finance for Development leverage private capital to maximize the impact of public financing.