The World Bank Group’s 2018 Capital Increase Package

Overview

This report presents the independent assessment, or validation, by the Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) of the World Bank Group’s 2018 capital increase package (CIP).

Purpose and Background

The CIP’s intention was to significantly expand the financing capacity of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) and the International Finance Corporation (IFC), thereby enabling both institutions to better achieve their strategic priorities. The CIP boosted the Bank Group’s financial firepower with a $7.5 billion paid-in capital increase for IBRD, a $5.5 billion paid-in capital increase for IFC, a $52.6 billion callable capital increase for IBRD, and internal savings measures. The CIP also committed IBRD and IFC to increasing their private capital mobilization (PCM) and financing for priority areas that were previously identified in 2016, in Forward Look: A Vision for the World Bank Group in 2030. These strategic priorities were the Bank Group’s enhanced engagement with all client country segments, an expanded role in leading on global themes and delivering global public goods, increased public and private resource mobilization, operating model’s increased effectiveness, and improved financial sustainability.

IEG conducted the assessment as an extended validation without the extensive data collection typical of a full-fledged evaluation. This report builds on management’s reporting, evidence from 25 IEG evaluations, and technical discussions with counterparts to assess IBRD’s and IFC’s progress in implementing the CIP’s commitments and policy measures, achieving its targets, and contributing to its intended outcomes. It also assesses the extent and quality of management’s CIP reporting. The validation has some limitations stemming from its underlying evidence sources. Much of the data come from the Bank Group’s monitoring indicators, which—like corporate indicators in general, are of uneven scope and quality—and are often unable to capture outcomes. The implementation status of some policy measures was also difficult to ascertain because of gaps or a lack of clarity in management’s reporting. As a result, the validation assessed policy measures and priority area outcomes with uneven depth. More broadly, a limitation of this validation is that, although there is no doubt that the Bank Group responded with speed and volume to the crises faced by client countries since 2019, it cannot make a clear causal attribution of this to the CIP.

Priority Area 1: Differentiating Support across Client Segments

IBRD’s reporting on the priority area of serving all clients has been satisfactory. Most of IBRD’s CIP commitments were specific and measurable, the reporting covered most commitments, and 11 reporting indicators were clearly linked to the commitments’ underlying objectives. IFC’s reporting has some shortfalls related to indicator precision.

IBRD has fully implemented its commitments for countries below the graduation discussion income (GDI). Its portfolio in these countries has grown steadily—from 60 percent in fiscal year (FY)17 to 76 percent in FY19—and has remained above the target of 70 percent. Country-level data suggest that International Development Association (IDA) graduation has not led to a decline in total World Bank lending for most IDA-blend and graduate countries.

IFC has made limited progress increasing its investment shares in IDA and in countries classified as having fragile and conflict-affected situations (FCS), despite IFC’s efforts to increase financing to these countries. IFC’s financing to low-income countries in the 17th Replenishment of IDA and in IDA FCS countries has fluctuated around an upward trend since FY19, but it averaged 9 percent as a share of its long-term own-account financing, which is below its low-end target for FY26 of 15 percent. IFC has increased its investments in all IDA and FCS countries, although it will need to grow faster to meet its ambitious targets.

IBRD’s lending for upper-middle-income countries (UMICs), or above-GDI countries, has remained more or less stable but below target. IBRD stopped distinguishing between crisis and noncrisis volumes; thus, it was not possible to validate this cluster’s target as it was originally defined. Country engagement documents for above-GDI countries did not systematically focus on strengthening policies and institutions, nor did they consistently focus on innovation, knowledge creation, and demonstration effects despite commitments and policy measures to this effect.

IFC’s ability to add value through financial features (for example, financing structure, innovative financing instruments, and resource mobilization) and nonfinancial features (for example, noncommercial risk mitigation, knowledge, innovation, and capacity building) is central to its value proposition in UMICs. To ensure that this value is realized, the CIP committed IFC to following a rigorous approach to additionality for private sector investments in UMICs. A recent IEG evaluation found that IFC’s support in UMICs is additional and that IFC does pay closer attention to documenting additionality in these countries (World Bank 2023a).

IBRD has met its CIP commitments to small states. The CIP included two very specific measures for small states, including an increase in the base funding allocation to these countries and a waiver from IBRD’s price increase for them. These measures, which went into effect in FY19, increased IBRD’s concessionality for small states and led to an increase in average lending volumes for small states. IFC’s commitment to using a regional approach for investing in upper-middle-income small states that leverages blended finance and other tools to limit investment risks in fragile and lower-income small states was not precisely defined and could not be validated.

Priority Area 2: Leading on Global Themes

Crisis response became an even more dominant theme for the Bank Group than was called for in the CIP. The Forward Look’s and CIP’s objectives were defined with the expectation that the Bank Group would need to respond to occasional major crises, but the reality has turned out differently, with the Bank Group being forced to respond to several major and overlapping crises. The Bank Group did so with a surge in financing for COVID-19 and other crises, enabled by the CIP, IBRD’s crisis buffer, and the front-loading and early replenishment of IDA funds.

The Bank Group has fully implemented its crisis commitments for countries affected by fragility, conflict, and violence (FCV). This includes IBRD’s crisis buffer allocation, which essentially sets aside IBRD funds for crisis lending, and a broad set of actions designed to shift from response to prevention. The Bank Group has strengthened its approach to FCV challenges. It adopted the FCV strategy (2020–25), introduced a new operational policy, strengthened partnerships with the United Nations and humanitarian agencies, and increased FCV funding. The FCV reporting stands out among corporate reporting for its depth and candor, particularly on the challenges of operating and achieving results in FCV contexts. The IFC commitments for this cluster were, first, to strengthen its partnerships and coordination on FCV approaches with the World Bank and other donors and, second, to increase IFC’s investments in high-risk FCV markets. It has been challenging for IFC to increase investments in FCV as intended because of the risks, complexities, and informality of FCV environments. Over the FY10–21 period, IFC’s long-term financing commitments to FCS have been relatively flat, averaging 5.2 percent of IFC’s total commitment volume and 8.6 percent of its total number of committed projects. However, IFC introduced or adapted a suite of instruments partly to target FCS, including upstream advisory services, blended finance, and country diagnostics.

IBRD’s and IFC’s reporting on their CIP gender implementation has been mostly adequate. Reporting was aligned with the gender strategy’s reporting and facilitated by existing corporate metrics on gender. The CIP gender commitments, indicators, and targets established by IBRD and IFC directly align with the Bank Group’s gender strategy. All six commitments have quantitative indicators and targets, which simplifies the reporting process. IBRD has exceeded its target of having 55 percent of its project designs close gender gaps, reaching 90 percent of all of operations approved in FY22. However, the gender indicators used within the CIP rely on the flag-and-tag methodology, which only captures the intent of projects during the design phase, and by their nature do not assess the quality, effectiveness, and overall outcomes of the World Bank’s and IFC’s interventions. More outcome-oriented metrics are not currently available. Moreover, whereas the gender strategy proposed a country-driven approach to narrowing gender gaps through multiple instruments acting in concert, in practice, implementation often took the form of stand-alone projects.

The CIP’s knowledge and convening cluster’s intended outcome was for the Bank Group to improve its knowledge and convening power to address global issues, but the cluster’s policy measures were not precisely defined, and its indicators did not capture the quality or effectiveness of the World Bank’s efforts in this area (which hampered reporting and validation of this cluster’s results). IBRD has implemented its policy measures in the knowledge and convening cluster. IBRD created the Strategic Framework for Knowledge, which captures the Bank Group’s current approach to knowledge management, and identified ways for the Bank Group to strengthen its knowledge management. IBRD also set up the global public goods fund to provide concessional finance for global public goods in middle-income countries. IBRD provided an initial $85 million in surplus funds to the global public goods fund as capital. Furthermore, both institutions widely share their data and research with the public; have taken steps to focus knowledge products on core diagnostics, such as the Country Climate and Development Reports and IFC’s Country Private Sector Diagnostics; and have made progress identifying knowledge gaps in country engagement products.

The World Bank has expanded and broadened its support for regional integration. More specifically, it has expanded its focus beyond Africa, and beyond its traditional focus on trade and infrastructure. However, the World Bank’s systems, accountability mechanisms, and incentive structures follow the country-driven model, and, in the absence of strong regional institutions and counterparts, it is often challenging to deepen the support for regional integration.

Priority Area 3: Mobilizing Capital and Creating Markets

This cluster had five policy measures that were monitored through two indicators that capture progress toward a part of the intended outcomes (namely, mobilization) and do not reflect the quality or effectiveness of the World Bank’s efforts in this area. At the same time, the CIP’s creating markets agenda involved a solutions package and the Cascade approach. These components comprise the overall narrative of Maximizing Finance for Development and are aligned with the broader directions expressed in the 2030 Agenda and From Billions to Trillions: Transforming Development Finance Post-2015 Financing for Development: Multilateral Development Finance discussion note. The concept of a solutions package implies the use of a combination of new and established Bank Group instruments in a mutually reinforcing way to crowd in private resources.

IBRD has made limited progress in mobilizing public and private capital as defined under the CIP. Its average annual PCM from FY19 to FY22 was 7.4 percent, well below its target of 25 percent. Following the capital increase in FY18, IBRD’s PCM ratio of mobilization to own-account financing decreased from 16 percent to 3 percent in FY21 but then rebounded to 9 percent in FY22, resulting in an average annual PCM of 7.4 percent between FY19 and FY22. Only in 2017 did IBRD meet its 25 percent mobilization target.

IFC’s core mobilization ratio has been 94 percent averaged over the CIP period, exceeding the illustrative target of 80 percent of own-account commitments. Its mobilization totals increased from $10.2 billion in FY19 to $10.6 billion in FY22, and its mobilization ratio dropped over the CIP period (falling to 84 percent in FY22), which was still above the CIP’s 2030 target of an 80 percent average.

The CIP’s market creation objectives were not fully articulated, and implementation was not systematic. Bank Group management took steps toward implementing Maximizing Finance for Development through the Cascade approach, including issuing guidance notes to incorporate the approach in country engagement products, establishing working groups, creating IFC upstream units, strengthening analytical capacity, and providing communication and training materials; however, there is little evidence that this led to operational work to create markets. IFC’s upstream operating model was launched in 2020 and envisaged a strong role for global units in supporting the creating markets strategy. In 2022, it moved most staff from these global upstream units to regional upstream units and further merged upstream and advisory teams. Furthermore, the Bank Group’s Cascade approach for creating markets was partially at odds with volume and process efficiency targets and related staff incentives. However, in the absence of a monitoring framework, there was no evidence that these efforts were systematic or successful; the reporting relied on individual examples.

Although the CIP has no formal domestic revenue mobilization (DRM) commitments, this area of work has become increasingly important because of fiscal deficits and high and rising debt levels in lower-income countries. The World Bank has intensified its DRM work since 2018 and pivoted toward tax policy. Evidence suggests that IBRD gave increased attention to DRM and tax policy and increasingly used development policy financing. IEG’s 2023 evaluation of the World Bank’s DRM work finds that the World Bank’s support was greatest in countries with low revenue–to–GDP ratios, such as those in Sub-Saharan Africa and IDA-eligible countries. Nonetheless, the World Bank has shown limited internal collaboration and policy coherence on DRM. Two evaluations uncovered weaknesses in the World Bank’s internal collaboration and planning related to DRM, including weak links between its diagnostic work and its operational work on tax reforms. At the same time, the Bank Group’s collaboration with external partners on DRM has improved. However, IBRD and IFC’s CIP reporting on DRM has been unsatisfactory. The CIP has no formal DRM commitments and no indicators for measuring DRM, and CIP’s annual reporting has described the World Bank’s DRM work in cursory fashion.

Priority Area 4: Improving the World Bank Group’s Internal Model

The CIP emphasized efficiency commitments to tighten budget discipline, whereas the Forward Look emphasized putting human capacity in place to deliver on the Bank Group’s various strategies. For example, the Forward Look proposed a new human resources initiative to strengthen staff capacity—the people strategy—which the CIP did not pursue. Instead, the CIP featured efficiency commitments to tighten budget discipline, deliver savings, and avoid costs.

World Bank management has taken steps during the review period to enhance the effectiveness of IBRD’s internal operating model. These steps include the following CIP policy measures: procurement reforms, the Agile Bank initiative, and the Environmental and Social Framework. The World Bank also undertook additional reforms to improve IBRD’s internal model effectiveness that were not explicit policy measures or commitments but were described in CIP progress reports, such as trust fund reforms; the decentralization of staff and decision-making; and Country Engagement Framework enhancements. The results from IBRD and IFC’s implementation of this cluster proved hard to validate because some key initiatives were abruptly discontinued without explanation and attempts to learn from them, many reform outcomes were unknown, and monitoring and reporting was inconsistent. For example, World Bank management discontinued the Agile Bank initiative without explanation, and CIP implementation updates from FY20 onward ceased to report on the Agile Bank initiative; therefore, its results are unclear.

IFC has implemented measures to enhance the effectiveness of its internal operating model in accordance with CIP mandates. The goals of these measures, as described in the CIP document, include trimming bureaucracy, simplifying approval procedures, enhancing the development impact of project portfolios, and improving organizational effectiveness. It is hard to assess the effectiveness of IFC’s operating model because of a lack of metrics and indicators, some reporting shortcomings, and the limited time IFC has been implementing these measures; however, initial results suggest that IFC’s portfolio approach and workforce planning have had some successes.

The CIP contained a single commitment to introduce a new Financial Sustainability Framework (FSF) for IBRD. The FSF’s purpose was to align IBRD’s lending with its long-term sustainable lending capacity, ensure efficient use of IBRD’s capital, and retain IBRD’s flexibility for responding to crises. IBRD fully implemented its CIP FSF measures and regularly updated the Executive Directors on its progress. Implementation of IBRD’s financial package increased IBRD’s capital base, increased its income from lending, and optimized its balance sheet. The FSF, including the crisis buffer, has allowed IBRD to increase its crisis lending and provide more fast-disbursing loans.

IFC has made good progress implementing all the relevant measures listed in its FSF and reporting them, including IFC’s active portfolio management, balance sheet optimization, pricing policies with minimum investment return targets, and income-based designations for advisory services. IFC’s capital base was strengthened during the CIP period, demonstrating its improved financial sustainability. The rating agencies provided positive assessments of IFC’s financial risk management.

Conclusions and Lessons

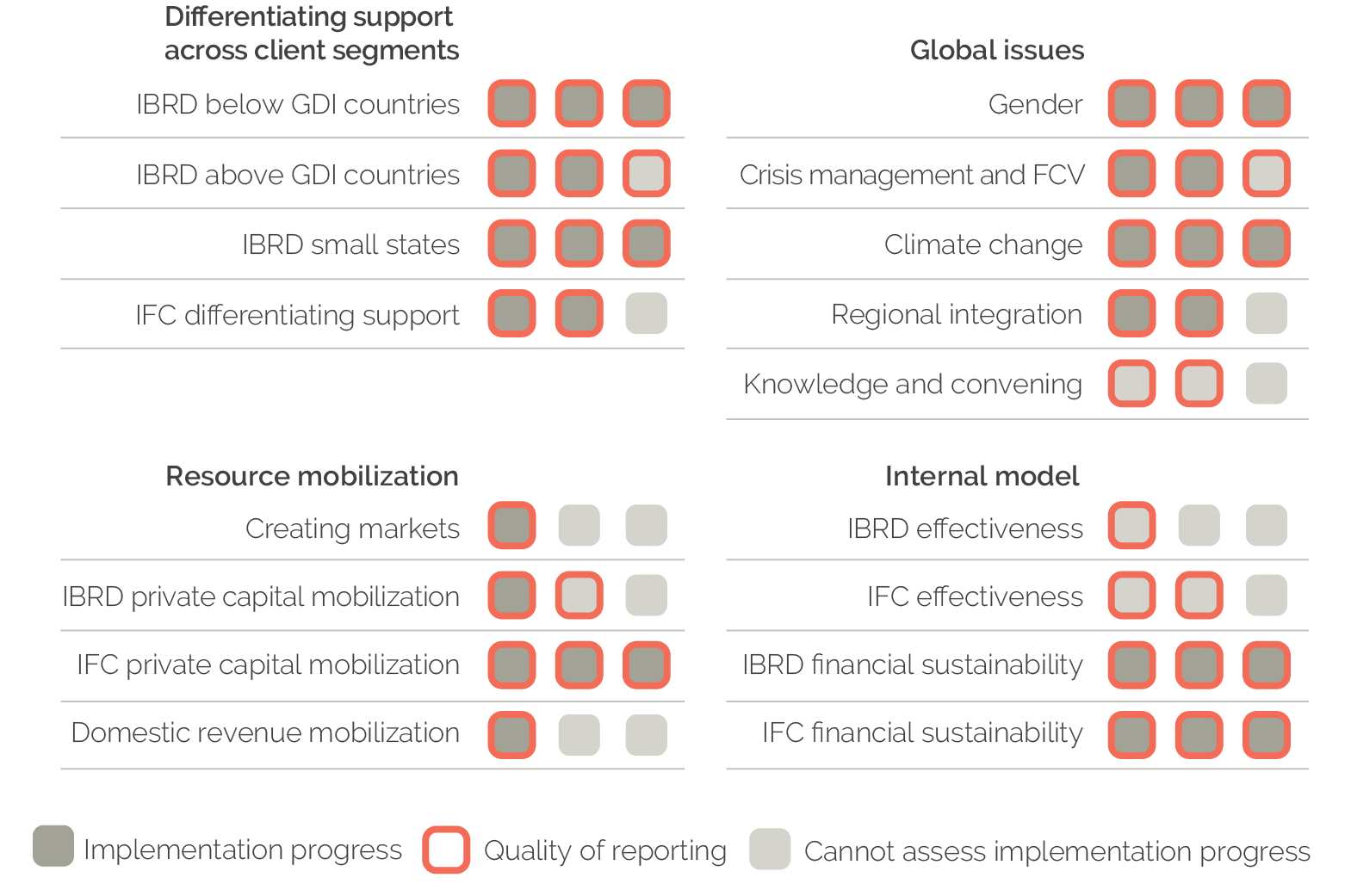

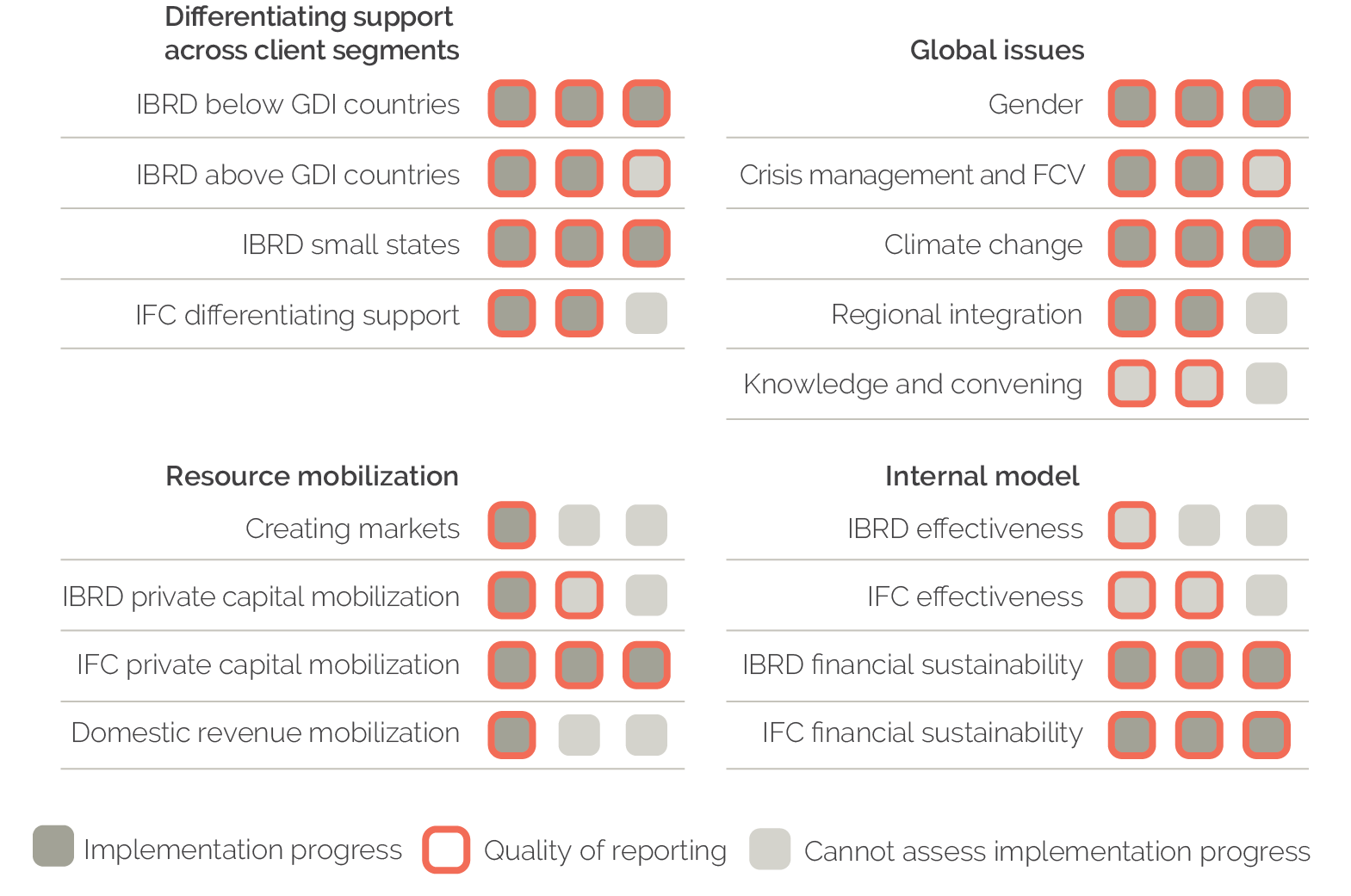

This validation shows that the Bank Group delivered many different major corporate commitments, even if it did not achieve all of its targets and objectives. Not only did the CIP infuse capital into IBRD and IFC, it also boosted the implementation of Bank Group priorities that already had corporate strategies and supportive internal arrangements in place, including for gender, climate change, and FSF. The CIP also had well-defined indicators and targets, and adequate reporting for these clusters. The Bank Group made the least progress in implementing clusters where policy measures were written as broad statements of intent and where it lacked clear strategies and measurable indicators or had limited oversight, weak collaboration, inadequate incentives, and overly ambitious targets. CIP reporting also had shortcomings in these clusters. Figure O.1 shows this validation’s rating of implementation progress and reporting across CIP clusters, showing clearly how instances with inadequate reporting were usually accompanied by limited implementation progress.

Figure O.1. Quality of Capital Increase Package Implementation and Reporting across Capital Increase Package Clusters

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The number of dark gray rectangles shows the validation’s ratings for capital increase package implementation progress: one rectangle = not achieved; two rectangles = partially achieved; three rectangles = achieved. The orange rectangles show ratings for reporting: one = major reporting shortfalls; two = some reporting shortfalls; three = adequate reporting. See chapter 6 and appendix A for the full criteria. FCV = fragility, conflict, and violence; GDI = graduation discussion income; IBRD = International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; IFC = International Finance Corporation.

The CIP’s five intended outcomes achieved differing levels of success. These are listed from most successful to either least successful or those with insufficient evidence for a more definitive assessment:

- Improving the Bank Group’s financial sustainability: This is the area with the clearest progress. The CIP’s capital infusion and financial sustainability measures clearly strengthened IBRD’s and IFC’s capital bases, thereby enhancing both institutions’ financial sustainability. Although outside the scope of this validation, the CIP allowed the Bank Group to swiftly and substantially respond to the crises that affected client countries after 2019.

- Leading on global themes: The Bank Group has undoubtedly expanded its role in promoting global themes during the CIP period. This includes delivering global public goods through its concerted response to pandemics, FCS, climate change, and other crises. As mentioned, this response was compelled by a confluence of global crises, but the CIP also facilitated this response.

- Differentiating support across client segments: The Bank Group continues to serve all country segments, and the country-based model continues to meet countries’ needs. The CIP led IBRD to focus more on below-GDI countries, and IBRD did meet its lending targets for these countries. IFC, for its part, has made limited progress toward its CIP financing targets for low-income and fragile countries, which, arguably, were overly ambitious for reasons that are not clear to this validation.

- Mobilizing capital and creating markets: The CIP saw limited progress in scaling up public and private resource mobilization. Although IFC has met or exceeded many of its mobilization targets, IBRD has not. This partly reflects the ambitious nature of the private resource mobilization targets for IBRD. At the same time, the Bank Group has lacked comprehensive strategies and support mechanisms to buttress its commitments and policy measures on DRM, PCM, and creating markets.

- Improving the operating model’s effectiveness: IBRD and IFC have made many changes to their operating models, though not necessarily those anticipated in the CIP. The outcomes of these changes have not yet been assessed. The CIP’s clearest, or at least most measurable, legacy in this area is its management of salary and workforce growth, specifically its reduction in GH-level staff. However, the reduction in high-level technical staff likely decreased staff capacity and morale with unclear effects on the Bank Group’s performance.

Five lessons emerged from the validation’s findings on developing, implementing, and reporting future corporate initiatives, including the CIP’s continued reporting:

Lesson 1: Success was greatest when corporate initiatives focused the Bank Group on areas with buy-in. Senior leadership’s buy-in and support are a necessary condition for the successful implementation of corporate initiatives. Many times, senior leadership demonstrates its buy-in by promoting corporate strategies or action plans, organizational champions, and changes to the Bank Group’s operating model. Shareholders could help increase the likelihood of success by ensuring that future policy measures are backed by a clear strategic vision, a conducive organizational model, and meaningful indicators and targets.

Lesson 2: Good indicators, with baselines and targets, create clarity, foster accountability, and contribute to a strategy’s sustained implementation. The implementation of some CIP commitments and policy measures lacked continuity, but this did not occur for commitments that were guard railed by measurable indicators and targets. Core corporate indicators and targets can be blunt tools, but they make required actions and reporting clear, become embedded in results agreements, compel business units to follow through on these issues, and ensure the implementation’s continuity in the face of changes to senior management and corporate priorities.

Lesson 3: Indicators should be aligned to commitments, and indicator monitoring should be grounded in routine operational processes. Reporting requirements multiply with the addition of new corporate initiatives and frameworks. Ensuring alignment between commitments and indicators and aligning indicators with those of existing corporate initiatives, systems, and frameworks will simplify the Bank Group’s reporting processes and ensure that corporate incentives are aligned.

Lesson 4: Corporate indicators are a blunt tool for capturing policy measure outcomes. Corporate indicators capture the Bank Group’s actions, processes, and outputs but do not capture what outcomes these actions led to or how policy measures interacted across clusters. This is because corporate indicators focus on activities and outputs that are under the Bank Group’s control. Although useful from an accountability perspective, this carries the risk that corporate indicators may perfectly measure the trees while ignoring the forest. To improve corporate indicators, the Bank Group could tap into their data-rich project monitoring and evaluation systems to develop metrics and assessments that better capture ongoing and ex post results. The Bank Group could also combine indicator-based reporting with periodic deep dives that focus on outcomes.

Lesson 5: Report with candor. Honest and accurate reporting on implementation challenges enables the organization to learn and adjust. As such, future reporting would benefit from greater candor on progress, challenges, and trade-offs. Management and Executive Directors may want to reflect on what signals they give to business units that report candidly on their successes and failures.