Creating an Enabling Environment for Private Sector Climate Action

Chapter 4 | Effectiveness

Highlights

The World Bank Group usually achieves its indicator targets related to enabling environment for private sector climate action, but these indicators are usually inadequate to assess whether private sector climate action is being achieved.

For renewable energy—the largest and most mature part of the portfolio—econometric analysis shows that World Bank lending activities have led to improvements in enabling environment and to investment in renewable energy in countries with high financial development. International Finance Corporation advisory activities have also led to increased private sector investment.

The Bank Group has often been effective at achieving improvements for enabling environments, although success is mixed for activities that require overcoming political economy challenges. Improvements in enabling environment have sometimes led to significant private sector climate action, but there are also many cases where private sector action has not occurred or where it is too soon to tell.

Key success factors include establishing price levels sufficient to incentivize private sector action, developing standardized and replicable business models, addressing affordability for poor people, and fostering institutional reform. However, the Bank Group has often supported business models that are not scalable, typically because they have allocated risks to governments in a way that is unsustainable, such as through guarantees or contingent liability for foreign exchange risks.

This chapter assesses the effectiveness of Bank Group enabling environment activities. It first analyzes the available evidence for the Bank Group EEPSCA portfolio. Next, it conducts a deep dive using econometric analysis on the effectiveness of enabling environment activities for renewable energy, where the World Bank has engaged on EEPSCA for the longest time and where the most data are available. Finally, it identifies success factors and challenges to effectiveness using case studies.

Portfolio Effectiveness

The Bank Group portfolio on EEPSCA is relatively young, and so effectiveness can be assessed only for a subset of projects. Out of the 268 World Bank lending projects, only 73 are closed and evaluated. For IFC AS, 58 out of 119 IFC AS are closed and have a self-evaluation, and 22 of these have an independent validation. Most closed projects are related to climate change mitigation, especially in the energy sector, because these activities were predominant in the early years of the evaluation period. This limits the degree to which conclusions can be drawn about the effectiveness of other Bank Group EEPSCA activities.

The Bank Group usually achieves its indicator targets related to EEPSCA activities. Most projects with EEPSCA activities also contain other interventions that are not focused on enabling environment and do not have objectives related to enabling environment; thus, it is not possible to use overall project performance or outcome ratings as a measure of success. Instead, the evaluation identified the project indicators that related to EEPSCA activities and assessed achievement of their targets. The World Bank fully achieved 73 percent of its EEPSCA-related indicator targets and partially achieved another 18 percent (that is, achieved 70 percent or more of the target), leaving 19 percent of indicator targets unachieved. IFC also fully achieved 70 percent of its EEPSCA-related indicator targets and partially achieved another 1 percent of its targets, leaving 29 percent of targets unachieved. It is difficult to determine whether these success rates are optimal because there is no clear benchmark. They are, however, similar to the broad 75 percent satisfactory outcome target set for World Bank projects in the corporate scorecard.

These success rates do not vary much across different types of enabling environment activity or other project characteristics. Indicator achievement rates were similar for activities that supported incentive changes through price or nonprice regulations, provided information to the market, or managed risks related to stakeholders. The large majority of indicators were for climate change mitigation; therefore, it was not meaningful to compare success rates for mitigation versus adaptation. There were no other obvious patterns in achievement rates.

For the World Bank, the main reasons for indicator nonachievement were lack of political consensus or government ownership, project implementation delays, force majeure, or unrealistic choice of targets. For the 19 percent of World Bank lending EEPSCA indicators that did not achieve or partially achieved their targets, the most common reason for lack of success was from a lack of political consensus or poor government ownership (8 percent of indicators). This was particularly common for energy reforms that required subsidy cuts or tariff increases. A DPF series in Panama could not sustain increases in power tariffs because of social opposition, whereas in Togo, the government was not willing to implement power tariff increases because of fear of political backlash. The other main reasons for indicator nonachievement were project implementation delays, where project self-evaluations argued that indicators would be achieved later, after project closure; force majeure (consequences of COVID-19 or conflict); or indicators that project evaluations concluded were unrealistic to achieve by the time of project closure.

For IFC, the main reasons for indicator nonachievement were project implementation delays, shortcomings in project design, lack of government ownership, or force majeure. For the 29 percent of IFC EEPSCA AS indicators that did not achieve or partially achieved their targets, the most common reason was project implementation delays (10 percent of indicators). However, several projects also failed to achieve results because of shortcomings in project design weaknesses or lack of government ownership. For example, a project seeking to assist the government of Odisha, India, to implement a home-based rooftop solar program was unsuccessful because the design did not take account of radical changes in the sector, where large developers shifted from housing to large commercial and industrial rooftops and where solar developers shifted from rooftop solar to utility scale solar projects. A project supporting Excellence in Design for Greater Efficiencies building standards in China applied a generic design that was insufficiently tailored to the local context and did not consider that the housing ministry had just completed its own revision of building standards. The choice and monitoring of indicators, which in some cases were retained for activities that had been dropped from the project design, were another reason for not achieving the targets. In a few cases, the reasons were similar to those for World Bank development policy operations—a reluctance by government to increase energy tariffs meant that utilities were not on sound financial footing, and thus lenders were reluctant to invest to projects that might be affected by this. Other reasons cited for nonachievement were force majeure from COVID-19 or conflict.

World Bank and IFC project indicators are rarely adequate to assess whether private sector climate action is being achieved. Project indicators for EEPSCA activities typically capture only improvements in the enabling environment (44 percent for World Bank and 45 percent for IFC) or output delivery (19 percent for World Bank and 22 percent for IFC) rather than evidence of private sector climate action (36 percent for World Bank and 33 percent for IFC). World Bank and IFC projects with only output indicators often measured things such as development or submission of reports or proposals, or completion of technical assistance. Although some indicators that captured improvements in enabling environment were quite meaningful, such as documenting changes in energy tariffs, others documented only the implementation of a policy change, or adoption of a standard, or the creation of a new mechanism and fell short of measuring the results of these changes. Only a subset of indicators explicitly or implicitly assessed whether enabling environment changes were contributing to the desired private sector climate action, including firms’ investment in a new technology, adoption of a behavior change, or use of a new financing or risk-sharing mechanism. World Bank development policy operations tend to capture private sector climate action better than World Bank investment loans. One reason for this is because EEPSCA actions in development policy operations had their own prior action, with its own dedicated indicators seeking to assess its impact, whereas EEPSCA activities in World Bank investment projects were often a small portion of the overall project and had indicators that concentrated on measuring the effects of project works rather than enabling environment activities. IFC AS sometimes did not include indicators of private sector action because their shorter time horizons meant that they would close before private sector actions would be achieved.

Some projects include good practice indicators on measuring private sector climate action. The best designed projects have included indicators that assess whether enabling environment improvements are leading to or likely to lead to private sector climate action, across different types of enabling environment constraints (table 4.1). Although projects need to select indicators that will be achieved and measurable by project closure, projects such as those in table 4.1 demonstrate that it is often feasible to select achievable and measurable indicators that also assess progress toward private sector climate action.

Table 4.1. Examples of Good Practice Indicators in World Bank Group Projects

|

Type of Constraint on Private Sector Climate Action |

Country, Activity, Institution |

Good Practice Indicator |

|

Incentives, price or nonprice regulations |

Egypt, Arab Rep., energy subsidy reform, World Bank |

Reduction in energy subsidies as a percent of GDP |

|

Vietnam, feed-in tariff for wind power, World Bank |

Generating capacity of grid-connected wind power |

|

|

India, economic instruments for cleaner technologies in polluting industries, World Bank |

Percentage of industries that have adopted environmental management systems in the state |

|

|

Provision of information to markets |

Ghana, sustainable banking regulation through environmental and social standards, IFC |

Value of investments financed in compliance with environmental and social performance standards of participating banks |

|

China, green building standards, IFC |

Energy use expected to be avoided (megawatt-hours per year) |

|

|

Tunisia, adoption of renewable energy plan targeting private sector through concessions, World Bank |

Solar power capacity of private sector–owned projects selected under the concession scheme |

|

|

Public sector institutions are not designed to deal with complex private sector contracts |

Rwanda, adoption of standard PPA approaches, IPP risk allocation, and competitive procurement procedures, World Bank |

Generation projects initiated or accepted by the government over the past 24 months are consistent with the least-cost power development plan and comply with PPP law and competitive procurement procedures |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: IFC = International Finance Corporation; IPP = independent power producer; PPA = power purchase agreement; PPP = public-private partnership.

Effectiveness of Renewable Energy Activities

The evaluation conducted a deep dive on enabling environment activities for renewable energy. Renewable energy is the largest and most mature part of the Bank Group EEPSCA portfolio and a sector where sufficient data are available to make statistical analysis feasible. Using econometric analysis, we assessed the impact of upstream and midstream Bank Group EEPSCA interventions through World Bank lending, World Bank advisory services and analytics (ASA), and IFC AS related to renewable energy on (i) improvements in the enabling environment for private sector participation in wind and solar renewable energy generation and (ii) attracting private sector investments in wind and solar energy generation in the years that followed.

The analysis tested the theory that upstream and midstream Bank Group interventions in renewable energy might induce countries to improve their legal and regulatory framework and that a more favorable business environment causes private sector investors to invest in renewable energy.

The econometric analysis used external data. The analysis used an external measure of enabling environment (the Regulatory Indicators for Sustainable Energy data set) and data on private sector investments in wind and solar renewable energy generation (the Private Participation in Infrastructure database), measured in terms of dollar amounts at financial closure. Robustness tests for private investments were conducted using data on energy generation and installed capacity as proxies (with data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development–International Energy Agency database and the International Renewable Energy Agency). The analysis uses a difference-in-difference methodology, which statistically compares the effect of the interventions on countries that received treatment (treatment group) with another group of similar countries that did not receive interventions (control group). Details of the methodology are provided in appendix A.

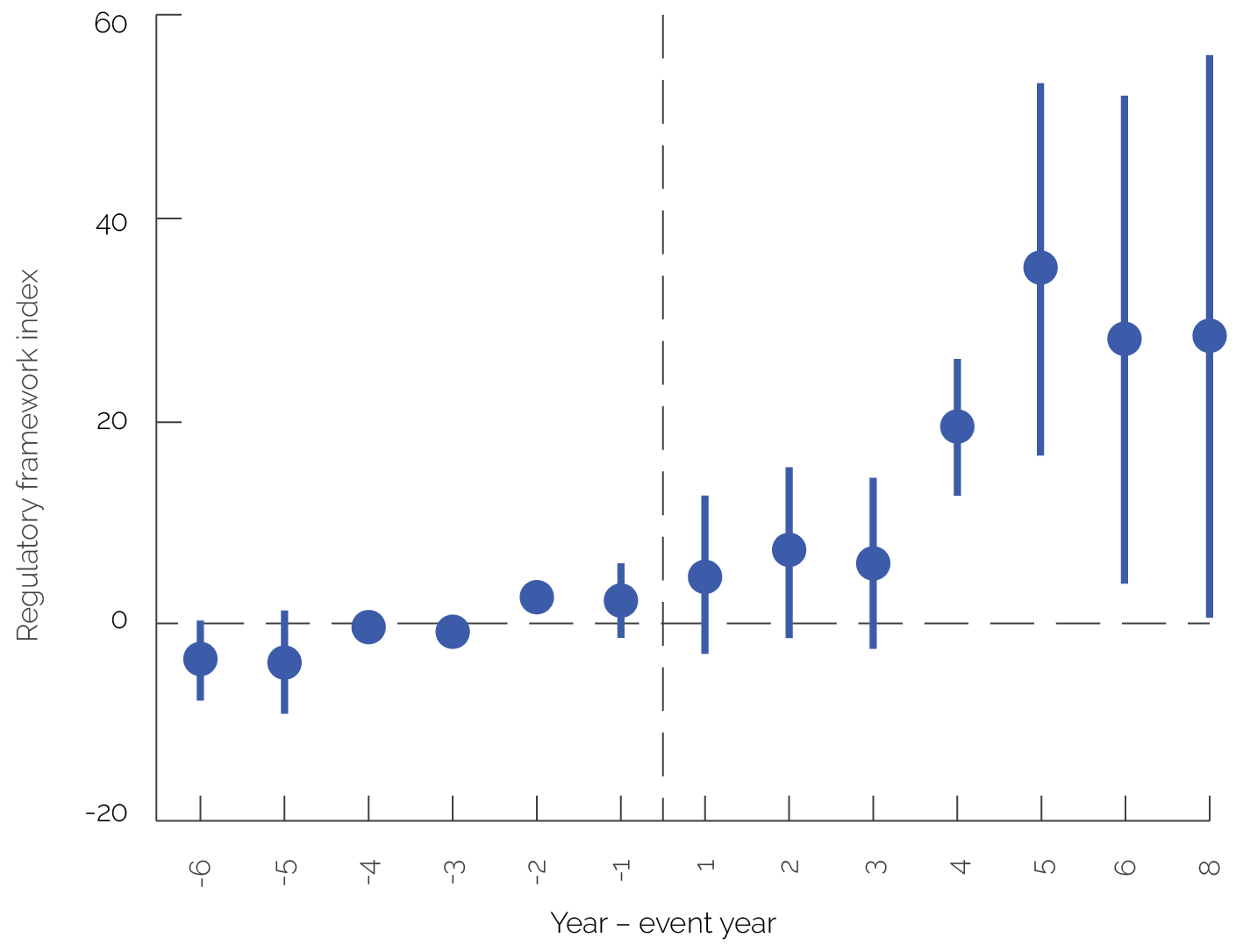

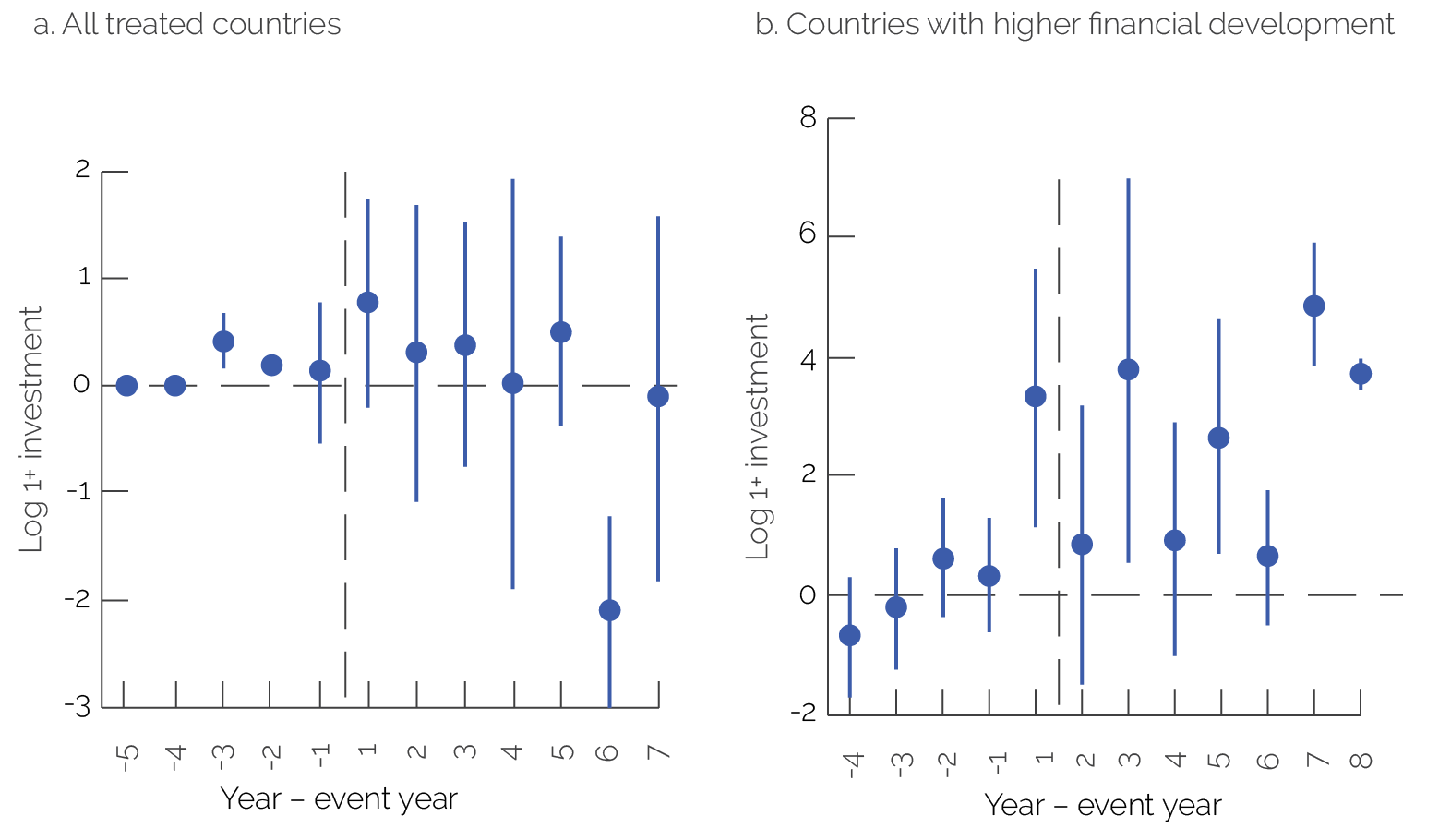

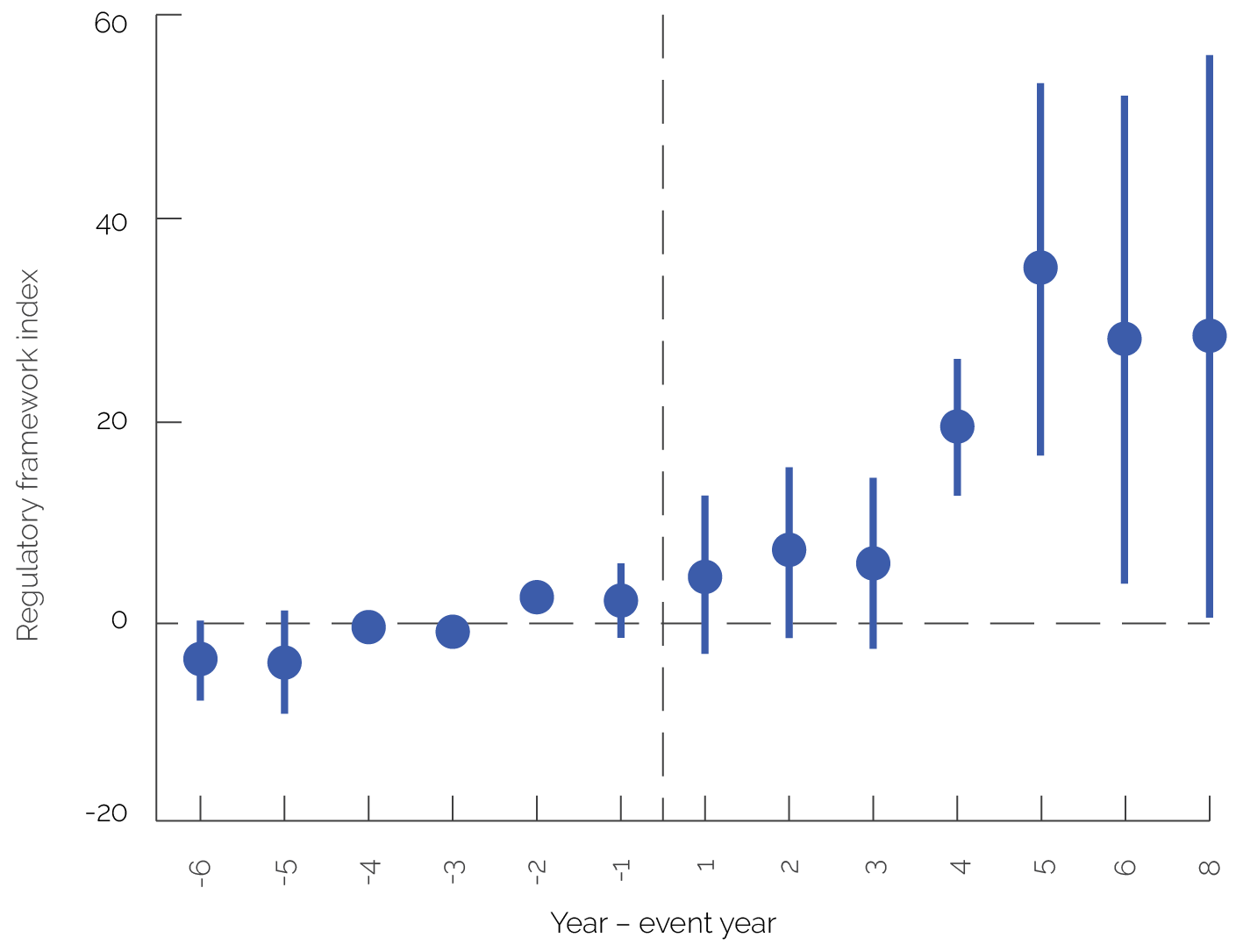

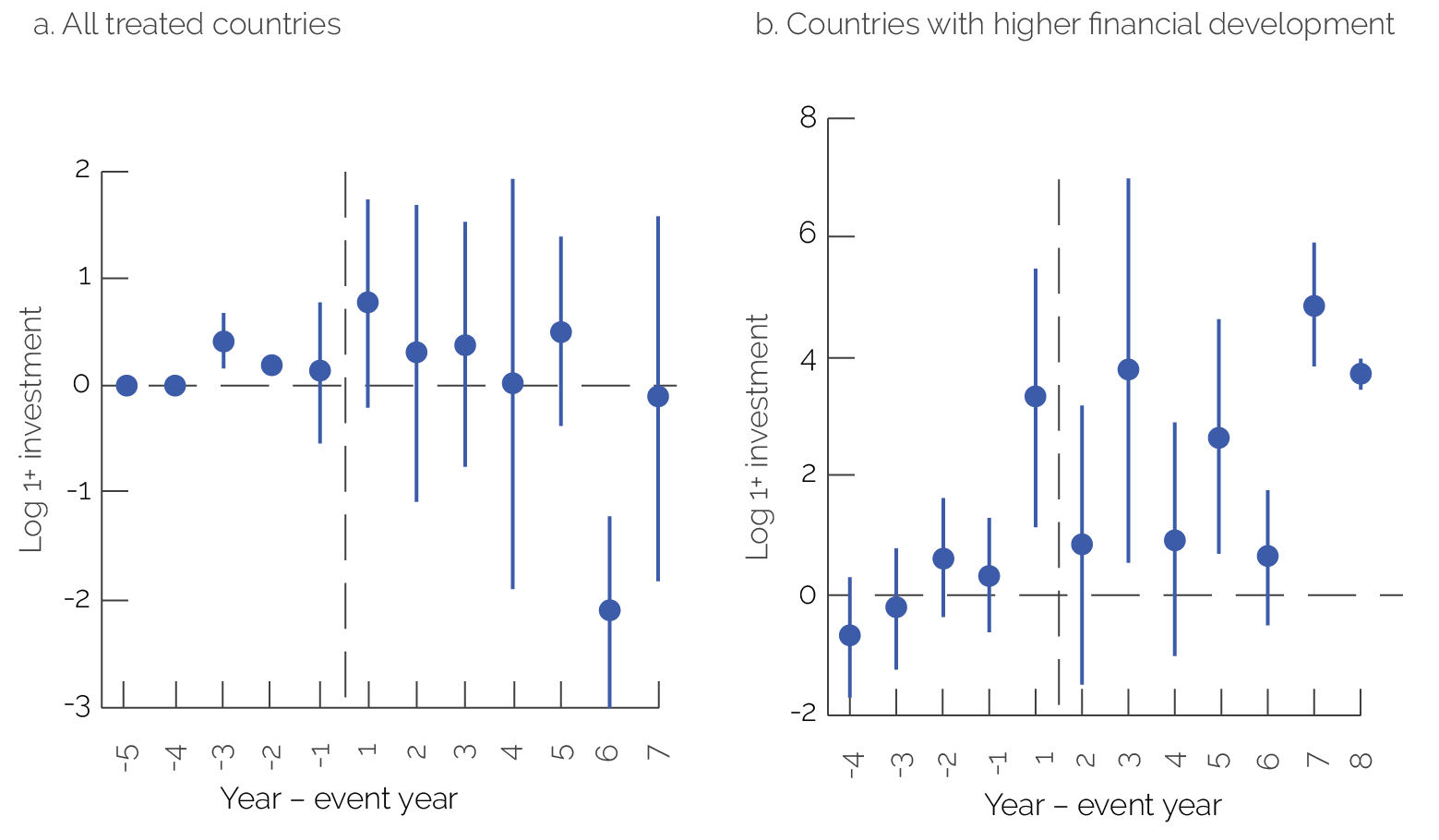

The econometric analysis finds that World Bank lending activities have led to an improved enabling environment for investing in renewable energy generation and increased private sector investment in countries with more financial development. As shown in figure 4.1, World Bank lending leads to a (weak) significant positive impact on enabling environment two years after the interventions and a significant impact after year four. This suggests that World Bank lending has been effective in supporting enabling environment reforms that improve the renewable energy regulatory environment. Although the impact of World Bank lending on private sector investments is inconclusive when tested for all countries in the sample (figure 4.2, panel a), the evidence suggests (weak) significance when tested for a subsample of treated countries with higher financial development, controlling for country income (figure 4.2, panel b; as defined by the International Monetary Fund Financial Development Index database).1 This shows that countries with greater financial development have benefited the most from improved enabling environment in terms of attracting private sector investments.

Both enabling environment improvements and financial development are needed to support private sector action in climate. Although these results of the econometric analysis confirm the World Bank’s catalytic role in supporting regulatory reforms that promote private sector participation in renewable energy, they also provide a warning about the effectiveness of these policies in countries with limited financial access. Improvements in the enabling environment might not be a perfect substitute for financial development. Investments in countries that are financially more integrated with the global market and are more known among the investors’ community have more funding opportunities compared with financially isolated countries with smaller banking sectors and underdeveloped capital markets. This implies the need to support both enabling environment and financial development improvements. It is beyond the scope of this evaluation to assess whether enabling environment and financial development interventions have been coordinated in these countries.

Figure 4.1. Staggered Difference-in-Difference Analysis—World Bank Lending on Renewable Energy Regulatory Framework

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis.

Note: Error bars are at 95 percent significance.

Figure 4.2. Staggered Difference-in-Difference Analysis—World Bank Lending on Wind and Solar Investments

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis.

Note: Error bars are at 95 percent significance.

Both enabling environment improvements and financial development are needed to support private sector action in climate. Although these results of the econometric analysis confirm the World Bank’s catalytic role in supporting regulatory reforms that promote private sector participation in renewable energy, they also provide a warning about the effectiveness of these policies in countries with limited financial access. Improvements in the enabling environment might not be a perfect substitute for financial development. Investments in countries that are financially more integrated with the global market and are more known among the investors’ community have more funding opportunities compared with financially isolated countries with smaller banking sectors and underdeveloped capital markets. This implies the need to support both enabling environment and financial development improvements. It is beyond the scope of this evaluation to assess whether enabling environment and financial development interventions have been coordinated in these countries.

IFC EEPSCA AS have been effective in attracting private sector investments in wind and solar renewable energy. These interventions are mostly transaction AS that support client countries, including subnational governments, in “the last mile” for attracting private investments. They include, for example, support in designing the auction for the creation of a solar farm or urban electrification of cities. It is plausible that the involvement of IFC in the design of the auction-built confidence among potential investors in the transparency of the process. Considering the operational nature of these services, it is not surprising that the evidence does not find that IFC AS projects improve the regulatory framework.

World Bank analytical work and AS for renewable energy have been effective in improving the regulatory framework, but we did not find clear evidence of its impact on attracting private sector investments. The econometric analysis also tested the effectiveness of World Bank ASA for renewable energy. The effects of the upstream and midstream policy interventions are positive and significant in improving the regulatory framework, but the effect on private investment was inconclusive. When tested for the impact on the proxies (generation and installed capacity) and for the subgroup of countries with financial development, the results were equally nonsignificant. These results should be seen as inconclusive (rather than evidence that nonlending work has been ineffective) because the large variety of interventions in World Bank ASA makes it difficult to identify which activities could plausibly lead to investment outcomes.

The evaluation also tested whether countries that received multiple EEPSCA interventions were able to attract more private investment in renewable energy. Although the difference-in-difference method assessed the impact of each intervention on enabling environment and investment, it was unable to test effectiveness of cumulative interventions carried out by the Bank Group. To address this, the evaluation used principal component analysis to assess the combination of World Bank lending, World Bank ASA, IFC AS, and IFC investment services. Principal component analysis develops a treatment intensity index that captures the information related to the number of EEPSCA interventions received by countries through the years. Through a nonparametric estimation, principal component analysis estimates the relationship between the treatment intensity index and the impact on private investments in renewable energy generation and private renewable energy installed capacity.

Countries that have received multiple Bank Group renewable energy interventions have also benefited from high private investment, but the effect is stronger in countries with more financial development. Although initial tests for the whole sample suggest that countries that have received more intensive Bank Group EEPSCA treatment have also been able to attract more private capital, the evidence is weak due to possible selection biases. We mitigated the selection bias by separating the sample between countries with higher and lower financial development. The analysis suggests that (i) countries with less financial development received fewer Bank Group renewable energy interventions and (ii) countries with more Bank Group renewable energy interventions benefit the most in attracting private investments when financial development is higher.

Effectiveness and Success Factors

The evaluation used case studies to identify factors that have supported or inhibited effectiveness and lessons. Each case study assessed the degree to which the Bank Group has contributed to improvements in enabling environment and the degree to which enabling environment improvements led to private sector climate action. Analysis of case studies also highlighted the degree to which supported business models included features that limited their ability to achieve impacts at scale. Table 4.2 provides a summary of the findings of the analysis, which are described in this chapter.

Achieving Effectiveness in Case Studies

The Bank Group has often been effective at achieving improvements to enabling environments using technical measures that do not impose significant negative effects on existing stakeholders. In most case studies, the Bank Group achieved at least some significant improvements in enabling environment. The Bank Group was most successful for constraints that could be addressed through technical measures that did not require significant trade-offs or impose negative effects on existing stakeholders. In Rwanda, the World Bank contributed to the government’s adoption of a least-cost power development plan, which incorporated a substantial role for the private sector, the adoption of a PPP law establishing competitive procurement procedures, and establishment of standardized PPA procedures. These provided clarity, certainty, and transparency to the private sector and contributed to substantial private investment, with 10 new private energy plants signing PPAs (compared with a signal new small public investment). In Colombia, the development of regulations better defining green investments and regulations modifying requirements for institutional investors has helped mobilize pension funds and others to invest in green infrastructure projects while complying with prudential standards.

The Bank Group has had mixed success for activities that require overcoming political economy and governance challenges, particularly from entrenched government stakeholders. Although these interventions are higher risk, they also offer potential for substantial impacts; therefore, the Bank Group should accept some tolerance for failure. For geothermal power in Indonesia, the World Bank was able to address capacity limitations for tendering processes, build a common understanding on development in conservation areas, and establish exploration risk-sharing facilities. However, it made limited progress on improving the pricing or process for PPAs (until a new regulation in late 2022) because this would require buy-in from the national power company. The power company had a limited incentive to undertake these actions because it faced pressure to minimize the supply cost of power, and thus was reluctant to pay more for renewable energy, and because it faced excess supply from existing generation sources, mostly coal, leaving little need for new PPAs. As a consequence, there have been no major private investments in geothermal power in recent years, and the risk-sharing facility remains unused. Nevertheless, if the enabling environment for geothermal energy could be improved to the point where projects were investible, geothermal energy could play a major role in helping the country to meet its long-term ambitions for phasing out coal. The World Bank’s efforts to improve the enabling environment for hydropower in Nepal were only partially successful because of the complex political economy. The World Bank convened stakeholders and sought to build consensus for reform. It was able to use DPF to support the drafting of a new electricity act that would liberalize the sector and allow private power plants to access the transmission grid and export power, and the issuance of a regulation requiring cost-reflective power tariffs. However, the key regulation has not been issued, and the act has been awaiting adopting by the parliament since 2020 (in part because of opposition from key stakeholders). As a consequence, investment in hydropower has been limited compared with its potential. Yet Nepal has substantial potential for hydropower, and exports of power to India could help substitute for coal power there.

Improvements in enabling environments have sometimes led to significant private sector climate action. In Türkiye, World Bank support to geothermal resource exploration through a risk-sharing mechanism helped stimulate private sector investment. Exploration had largely ceased after the end of a publicly funded exploration program, but now with the mechanism, 2 subprojects had completed drilling as of January 2023, 4 were about to start drilling, and 21 were shortlisted. In Colombia, revisions to the legal framework and new regulations contributed to a substantial increase in usage of electric buses—from near zero at the beginning of the program to 973 in 2022. The use of electric vehicles and bicycles increased, and air pollution declined. Efforts to incorporate climate mitigation and resilience practices into privately financed roads were also successful, achieving $13 billion of projects in operation, including $4.5 billion in domestic financing. Success on private sector action should also not be determined solely on the quantity of private sector action but also the quality, in terms of costs imposed on governments or consumers. As discussed in this chapter, some models have generated private sector climate action only by building up government contingent liabilities (which may generate some private investment but inhibits scalability).

Private sector action has not occurred in several cases because enabling environment efforts were partially successful, political economy challenges stymied reforms, important constraints were not addressed, or macro and financial contexts for private sector development were unsupportive. In Ghana, the World Bank has been unable to engage substantially on most constraints for several reasons, most prominently the difficulty in generating buy-in from the cocoa parastatal. Efforts to support hydropower in Nepal have not been successful because the key reform law remains unpassed. In Indonesia, efforts to catalyze geothermal power investment have been unsuccessful because prices have not been high enough to attract investors, although a new regulation with higher prices was issued in late 2022. In Türkiye, the unfavorable macroeconomic situation means that financing is highly constrained, and energy service companies’ balance sheets are not strong enough to meet banks’ loan conditions; thus, efforts to expand this model have been only modestly successful.

Table 4.2. Summary of Case Study Effectiveness

|

Case Study |

Improved Enabling Environment? |

Private Sector Climate Action? |

Scalable? |

|

Colombia transport sector |

✓ |

✓ |

Local currency guaranteesa |

|

Colombia sustainable banking |

✓ |

? |

n.a. |

|

Egypt, Arab Rep. energy subsidy reform |

✓ |

✓ |

n.a. |

|

Egypt, Arab Rep. renewable energy |

✓ |

✓ |

Foreign exchange guarantees |

|

Ghana cocoa forest management |

x |

x |

No business model developed |

|

Honduras climate-smart agriculture |

✓ |

x |

Donor finance |

|

Indonesia geothermal power |

? |

x |

Projects not bankable |

|

Indonesia sustainable banking |

✓ |

? |

n.a. |

|

Nepal renewable energy |

? |

x |

Excessive risks for large hydropower |

|

Nepal sustainable banking |

✓ |

? |

n.a. |

|

Rwanda renewable energy |

✓ |

✓ |

No scalability constraints identified for grid RE |

|

Türkiye new renewables |

✓ |

? |

No scalability constraints identified |

|

Türkiye energy efficiency |

✓ |

? |

ESCO projects not bankable |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group case studies.

Note: These are all simplifications of complex situations. ✓ (check mark) = largely successful; ? (question mark) = mixed success or too soon to tell; x = unsuccessful. Emphasized text shows business models that are generally scalable (italic), partially scalable (bold italic), or have elements that inhibit scalability (bold). ESCO = energy service company; n.a. = not applicable, as some activities are not promoting specific business models. a. In Colombia, early models for green highway public-private partnerships relied on guarantees, although later did not.

In many cases, despite the Bank Group engagement on elements of enabling environment for several years, it is still too soon to tell if these will lead to private sector action. Supporting the full chain of activities needed to catalyze private sector climate action can require years of dedicated support. For example, in Türkiye, IFC AS was highly successful in developing and operationalizing a national certification framework for green organized industrial zones, but the full impact of the framework will materialize only after further legislation and efforts to address financing barriers. In all three cases on sustainable banking (Colombia, Indonesia, and Nepal), the Bank Group has provided advice based on rapidly evolving global best practices. Awareness of banks and their regulatory and supervisory authorities of climate risk has improved, and key regulations have been issued on climate risk classification and reporting, but countries are still early in the process of assessing the climate exposure of their financial systems. For example, in Nepal, IFC helped the central bank establish environmental and social risk management guidelines and regulations that require 62 banks and financial institutions to comply with the guidelines by reporting on their portfolios. However, delays in mainstreaming the guidelines into their lending practices mean that changes in business behavior have not yet materialized. In addition, insufficient enforcement of the reporting requirements may have created unfair competition because banks that meet the requirements and collect the necessary data from their customers are seen as more difficult to work with and so are at a competitive disadvantage.

Factors of Success

Policies that ensure that price levels are sufficient to incentivize private action have been critical to success or failure, although the World Bank has rightly migrated from models such as feed-in tariffs to auctions. Price incentives are at the core of investment decisions because the private sector is willing to tolerate substantial risks if it is compensated for these. Achieving sufficient price levels for clean technologies, both by adopting incentive policies and by removing subsidies or supports for less resilient alternatives, has played a major role in the success or failure of EEPSCA interventions. However, the literature suggests that initial successful approaches to price incentives, such as feed-in tariffs, are no longer needed to incentivize investments in standardized technologies and that auctions can reduce the cost of new projects, with the exception of small projects (Dobrotkova, Audinet, and Sargsyan 2017; United States Department of Commerce 2023). In Indonesia, the requirement that PPA prices for geothermal power could not exceed the average supply cost in local grids, which were largely driven by subsidized coal power, meant that the private sector was unwilling to invest and that innovative geothermal exploration risk-mitigation measures were left unused. For rooftop solar in Türkiye, adoption of net metering replaced an expiring feed-in tariff program, providing significant incentive for households to purchase solar systems.

World Bank and IFC capacity building has played an important role in building the ability of government to design and implement policies and for the private sector to adopt climate action. Insufficient institutional capacity or awareness was a commonly diagnosed constraint. For example, low awareness of firms and banks on energy efficiency options constrained their ability to undertake energy saving investments. Limited capacity of government agencies to design and implement auction mechanisms or advanced contracting inhibited their ability to encourage private sector participation, and IFC transaction advisory helped address this. The Bank Group has provided capacity-building support as part of virtually all of its EEPSCA activities, either as subcomponents in lending projects or through stand-alone advisory. Government agencies frequently benefited from capacity-building efforts that expanded their ability to undertake key technical, legal, and financial activities. However, capacity-building efforts were seldom well monitored, as project indicators rarely measured capacity or capacity improvements in a tangible way, relying on output data on training programs. In a few cases, failure to address capacity limitations was a contributing factor to a lack of success.

DPF has played a powerful role in supporting critical policy changes related to EEPSCA, although they sometimes face barriers to implementation. In Nepal, the use of DPF helped leverage the authority of the Ministry of Finance to ensure progress on reforms by other government institutions and provided some degree of continuity in sector reforms in a context of frequent changes in key ministerial and top civil servant positions. However, the instrument was unable to overcome opposition from other internal stakeholders that opposed to reform the electricity sector. In Indonesia, DPF included a prior action supporting standardized procedures for PPAs, but the procedures were never fully adopted in part because of a lack of support from key stakeholders.

Government support and compensation to vulnerable populations for policies that seek to correct climate-related externalities are important to mitigate harmful effects. External literature points to the importance of supporting vulnerable groups when carbon price policies are adopted (IMF 2013; Sanghi and Steinbuks 2022). Although the Bank Group has limited ability to influence political support for reforms, it can advise on measures that help mitigate the side effects of these measures on vulnerable populations and consequently avoid their possible reversal. In the case of Egypt, the World Bank supported the government in energy subsidy reductions in 2014–17, including advice on a program of household subsidies that targeted vulnerable groups. The implementation of the subsidy reduction program took place gradually to give time to households and corporations to adapt, and for the first two years did not affect liquefied petroleum gas subsidies, which are a source of energy used mostly by lower-income families. The Bank Group supported progressively other social programs for affected populations, including conditional cash transfer programs. Although some energy subsidies still remain in Egypt, the adjustment was close to 7 percentage points of GDP between 2014 and 2017, and mitigation measures were important to alleviate the impact of the reform on poor people.

After the COVID-19 pandemic, most countries are better prepared to identify vulnerable population groups, which could make targeted compensation more feasible. As documented in the forthcoming Independent Evaluation Group evaluation on financial inclusion (World Bank 2023a), the COVID-19 pandemic brought better technologies to governments for identifying vulnerable populations and reaching out to them through cash transfers. During the pandemic, many countries started to use electronic cash transfers to support their populations. As part of strategies for mitigating the side effects of carbon pricing on vulnerable populations, the Bank Group may want to consider working with governments also in mitigation policies, while carbon pricing policies are introduced.

Bank Group models that address affordability constraints by low-income households and smallholders have been critical for achieving climate action by these groups. Climate action by smallholders or low-income households often faces serious affordability constraints. Successful Bank Group approaches have found ways to address these by incorporating subsidized financing mechanisms. For example, private sector off-grid companies in Rwanda were unable to expand beyond higher-income households at first, but access among lower-income households expanded significantly after providing them with subsidies through a World Bank–financed renewable energy fund. As a result, most new connections were for the poorest households.

IFC has played a valuable role in bringing investor and firm perspectives into policy dialogue and building the capacity of the private sector to engage. A particular strength of IFC has been its ability to consult and engage with the private sector and raise its awareness on a range of climate related issues, including on how to comply with upstream regulations. For example, in Colombia, IFC’s analytical and advisory work on incorporating performance standards for environmental and carbon reduction rules under PPP contracts met the need of the private sector to understand the commercial feasibility of such projects and cost and price in the cost of such measures in its bids. In the case of Egypt renewable energy projects, IFC was instrumental in reaching an agreement with the government regarding the terms of the contract that would facilitate project bankability, including the need of having an impartial system for dispute settlement. IFC also brought expertise on project finance structures and related risk management regulation to improve the design of private sector contracts.

IFC has played a leading role in initiating Bank Group action on topics such as sustainable banking. It was a pioneer in Bank Group efforts to promote sustainable banking regulations, initiating programs in Nepal and Indonesia that later received World Bank support and working as part of a joint Bank Group program in Colombia. Its advice to financial regulators and central banks, through the Sustainable Banking and Finance Network, laid the foundations for ongoing reform programs.

External factors, such as standards imposed on imports, have shifted incentives, unlocking action in a way that was not possible from domestic policy dialogue and capacity building. In Ghana, standards for cocoa certified as produced without deforestation helped motivate adoption of sustainable practices, as these offer a price premium. In Türkiye, desire to harmonize legislation with the European Union has been a driving force for electricity market development and reform. In Honduras, a desire for coffee exporters to receive international certifications, such as those for organic produce or for avoiding deforestation, helped encourage adoption of practices so that growers could access specialty export markets.

Institutional reforms that seek to create structures conducive to private investment have been a key determinant of enabling environment success. In many countries, institutional structures have favored state provision of infrastructure, with a limited role for the private sector. Many countries have large national energy utilities that are not supportive of a major role for the private sector. Reforms that open access or establish a clear role for the private sector have been critical. The ability to develop institutional structures that provide a development strategy incorporating the private sector accompanied by a defined pipeline of projects in the power sector in Rwanda, for example, played an important role for unlocking investment. Before Bank Group interventions, most new infrastructure was driven by bilateral, and sometimes opaque, agreements without a planned strategy, leading to high costs and low investor trust, but a new regulatory framework with standardized contracts and competitive procurement played a major role in mobilizing the private sector. In the case of Egypt, despite successful engagements in the renewable energy sector that allowed the attraction of private sector capital to renewable energy, economywide productivity has stagnated. According to the 2022 Systematic Country Diagnostic for Egypt, public sector institutional reforms are on the critical path to dynamizing the role of the private sector. These reforms that facilitate greater risk-sharing would be essential for the renewable energy sector to continue to grow.

Developing standardized business models has helped facilitate private investment in climate mitigation sectors, especially wind and solar power. Standardized approaches to contracts and regulations help attract investors by improving transparency and bringing predictability in the selection process and the rights and obligations of the different parties, reducing investor uncertainty. Standardizing includes both practices within a country to create a level playing field and adopting some standard best practices across countries, though still allowing differences based on country context. Standardization applies to elements such as contract and dispute settlement terms, procurement processes, and technical requirements. For example, in Egypt, IFC played an important role in bringing the private sector perspective to the conversations with the government in terms of creating a bankable contractual framework for multiple midsize contracts. The initial procurement round was unsuccessful because of lack of agreement on the arbitration terms, but IFC helped broker an agreement and unlock private investments in solar for approximately $2 billion in the second round. In Indonesia, the inability to establish standardized contracts and prices for geothermal power and the need for contracts to be individually negotiated with the national power utility were a barrier to investment. In Rwanda, shifting contracts for new power plants to a standardized procurement system rather than bilateral agreements helped build investor confidence that the process would be fair. In Colombia, IFC support for prefeasibility studies helped identify the viability of electric bus business models, which was critical to subsequent investment. IFC has had success in many countries with its standardized approach to scaling solar power.

Factors That Inhibit Scalability

It is critical that business models established with Bank Group enabling environment support have the potential to scale to meet the needs for climate investment. This section describes how some business models supported by the Bank Group through EEPSCA activities have included factors that supported or limited their scalability. Limitations to scalability were primarily due to allocation of risks to governments in a way that is unsustainable. Although there is an argument for government to adopt risks early in the development of a new industry, business models need to adjust over time to adopt scalable approaches.

Business models supported by the Bank Group for private investment in large public infrastructure projects have sometimes involved a buildup of currency risk for governments. In many case studies, the Bank Group has supported enabling environment activities that seek to trigger private investment in large public infrastructure projects. Most of these climate mitigation projects are in the nontradable sector, including those in energy and urban and road transport. Although revenue generation from these projects comes from domestic users paying tariffs in local currency, in most cases financing has come from international sources creating currency mismatches. A common PPP business model, especially for the energy sector, involves a government-guaranteed contract promising a stream of payments made to the investor company for a number of years, at a tariff structure that involves some level of adjustment according to the value of foreign exchange currency (foreign exchange indexation) that satisfies the investor. Although this contractual framework makes projects bankable, it requires the government to hold currency risks for years, with limited possibilities for mitigating the risks. In road programs in Colombia and renewable energy in Türkiye and Egypt, governments initially took on the foreign exchange risks to facilitate private investments, and these were successful in kick-starting the sector.

Accumulation of currency risk can impose a significant fiscal burden. Although the business model described in this section can work at the scale of a group of projects, it might not be suitable for financing the entire climate agenda because of the fiscal implications. After periods of macroeconomic instability, exchange depreciations in many client countries have created an increase in government financial obligations to private sector providers. For example, in the past five years (as of April 2023), currencies in Colombia, Egypt, and Türkiye have depreciated 65 percent, 75 percent, and 375 percent, respectively, against the US dollar, dramatically increasing the cost of the government obligations. In Egypt, the Bank Group–supported enabling environment improvements helped trigger a group of projects supported by IFC in connection with the Benban Solar Park. These projects reached financial closure in October 2017, with an average PPA tariff paid by the government utility of $0.071 per kilowatt-hour. This tariff was to be adjusted based on exchange rates, so that 70 percent of US dollar fluctuations would be reflected in the tariff. Measured in local currency, exchange rate depreciations meant that the tariff in April 2023 would be approximately 53 percent more expensive to the government than its value in October 2017.

The potential fiscal burden limits the scalability of these business models. The magnitude of the ensuing financial obligations means that governments cannot continue to offer these terms for new investments without further jeopardizing fiscal stability, especially for governments that already face high levels of debt (Hausmann and Panizza 2011). For example, in Egypt, for the period 2022–40, the CCDR identifies investment needs for renewable energy to be approximately 10 percent of the GDP. With a government debt-to-GDP ratio already in the range of 90 percent, a PPP model relying on government foreign exchange guarantees may face resistance from investors in supporting the scale of needed investments. In the case of the fourth generation Colombia road programs (2014–15), supported by the Bank Group, the government built up very high foreign exchange liabilities through guarantees on availability payments and revenue payments to concessionaries. The fifth generation of road PPP no longer offers foreign exchange guarantees, while it supports domestic financing of projects. Although it is too early to tell whether these projects will get financing, with the Bank Group support, the government approved amendments to the law that facilitate investments of pension funds in infrastructure projects.

Indexing consumer tariff rates to exchange rates to pass risk on to consumers is not a feasible solution. For nontradable sectors, such as transport and energy, countries may have difficulty in defining tariff structures for final users that are linked to foreign currencies. Theoretically, it could be done, but in practice would be difficult to implement as it would require tolerating volatile price swings for households and vulnerable populations.

Long-term currency hedging is also unlikely to be an immediate solution. Long-term currency hedging markets are unlikely to develop in countries with a small domestic investor base. Although IFC and other multilateral organizations offer longer-term currency hedge quotes (foreign exchange currency swaps) for some clients, in the absence of markets where domestic investors are willing to hold these risks, prices tend to be expensive compared with more liquid markets. In the absence of the development of domestic capital markets, the price of these foreign exchange swap mechanisms will continue to be expensive (BIS 2019). Although the provision of short-term foreign exchange currency swaps might help in some cases, in countries with high-interest rate volatility, prices of these instruments might be too expensive to ensure project bankability.

Scalable approaches to private financing of climate action will require the deepening of the domestic capital market and financial sector. Scalable approaches will require long-term debt financing either in local currency (Essers et al. 2014; Park, Shin, and Tian 2018) or in foreign currency but swapped into local currency using market hedging instruments. Such approaches would optimize the provision of government contingent liabilities and minimize those in foreign currencies. The Bank Group could contribute by supporting the creation of mechanisms that increase private savings that enable the development of long-term investors, including contractual savings mechanisms, such as pension funds and annuity companies, and encouraging their participation in climate financing. These developments could contribute to fostering domestic financing of projects and also to the creation of a long-term foreign exchange currency swap market. In the case of the Colombia roads, the World Bank supported actions to enable the participation of domestic pension funds through the creation of debt funds. Such actions enable the financing of projects without requiring government foreign exchange support. In Nepal, because tariff indexation for hydroelectric generation projects is linked to the local currency, interest from international investors has remained low. Under these contractual conditions and the absence of domestic capital market development, private investment in hydropower will remain a challenge. Globally, it will become increasingly difficult to mobilize private investment into large climate-related public infrastructure projects in the absence of policies that foster domestic capital market development.

Public sector guarantees have facilitated engagements of private sector investments. In the context of incomplete information and lack of track record of governments dealing with private sector contracts, such as PPAs, the private sector finds comfort in the provision of guarantees. Public guarantees help make private sector investments possible by enabling them to attract financing at low cost. For example, PPAs in Egypt enabled $2 billion of investments in renewable energy. Investors prefer standardized public guarantees rather than real asset guarantees. However, public guarantees in countries should be perceived mostly as an entry point for attracting private investors rather than an instrument for permanent financing of climate-related investments.

Excessive use of government guarantees can also inhibit scalability. As in Colombia, PPP concessions for toll road projects received government guarantees that mandated minimum payments regardless of road user numbers. During the COVID-19 pandemic, when road travel declined, some of these guarantees triggered and the Colombian government had to make payments to private sector companies. Besides the fact that the payments to private companies were triggered at a moment of significant fiscal constraint, the model of allocating the risk of traffic to the government has proven to be suboptimal.

Literature on toll road PPPs finds that flexible-term contract models for concessions offer a better risk allocation and avoid the use of public guarantees. Although it is common for countries to offer PPP concessions for a fixed term and organize bidding processes based on the lowest tariff, investors in these contracts typically require some form of government guarantee, such as a minimum traffic requirement, because traffic estimates have resulted in significant inaccuracies (Engel, Fischer, and Galetovic 2001, 2013). Flexible-term contracts (in terms of the number of years) offer a solution to this dilemma by extending the concession term if traffic volumes are below expectations and thus mitigate the investor’s risk without requiring a public guarantee. Under these models, bidders compete based on the present value of revenues. These models have been successfully operating in Chile since 1999.

In the context of high levels of government indebtedness and sizable needs for climate-related public infrastructure, risk allocation approaches should optimize the use of public guarantees when supporting projects. Governments could be better off if instead of allocating projects at the lowest up-front cost, using guarantees in foreign currencies, they allocated projects with slightly higher tariffs but with guarantees in local currency. Following the example of Egypt Benban energy projects, the government would be better off today if the tariffs with the energy generation company were 30 percent higher, but the indexation formula was initially set in local currency. By the same argument, governments would be better off by allocating toll road concession with no government guarantees, but a flexible duration of the concession period, than offering minimum traffic guarantees, but for a fixed concession period (for example, 20 years). The opportunities for risk diversification increase as domestic financial and capital markets become more sophisticated. Considering the high level of government indebtedness of many countries, the business models for attracting private capital supported by the Bank Group should factor in the need of optimizing the use of government contingent liabilities.

There are also cases where some enabling environment improvements have been achieved, but the models supported by the Bank Group may not be scalable because of a reliance on donor finance. Development finance is always likely to be limited, and business models supported by it should have a clear strategy for transition. In Honduras, the model pursued by the World Bank supplies matching grants to smallholder farmers to finance on-farm investments. Although the evidence shows stories of success among small farmers having access to finance and selling their products abroad, the program relies on International Development Association resources to provide this match, which covers 60 percent of subproject financing. This means that model cannot expand beyond the availability of concessional donor financing, and consequently the scale of the program is very limited; projects operating since 2008 have reached only 12,878 smallholder farms, in a country with an estimated 270,632 smallholder farms, and there is only weak evidence that the project is increasing agricultural finance beyond the direct loans subsidized by the program. In addition, only a limited set of CSA practices have been adopted in part because CSA was introduced more recently as a theme to an established program, and the program has not yet been made conditional on CSA. The main practice adopted was use of organic fertilizer, which may help farmer income by allowing them to reach specialty coffee buyers with a price premium, but the impact on climate resilience might be limited. In Rwanda, efforts to support off-grid solar also relied on donor finance, but the model had a finite end point of universal access, and long-term growth in energy consumption would be met by grid expansion.

- Financial development is defined as a combination of depth (size and liquidity of markets), access (the ability of individuals to access financial services), and efficiency (ability of institutions to provide financial services at low cost and with sustainable revenues, and the level of activity of capital markets).