Creating an Enabling Environment for Private Sector Climate Action

Chapter 3 | Relevance of World Bank Group Country Analytics and Sector Engagements

Highlights

Country climate diagnostics, especially Country Climate and Development Reports, describe actions needed to address climate change in each country, including the role of the private sector. However, they offer uneven depth across sectors in their analysis of the enabling environment needs for bringing private sector investment, they often do not offer realistic proposals for financing the proposed investments, and they propose green financing without addressing the limitations of the country context for green financing instruments.

The World Bank Group uses sector-based diagnostics well to identify the most important constraints on private sector climate action at the country level.

The Bank Group usually engages on the most important constraints identified by the diagnostics, and when it does not, it is typically because of a lack of government buy-in or political economy constraints.

This chapter assesses the relevance of the Bank Group’s country and sector analytics for EEPSCAs, the degree to which core country-level diagnostics identify priorities for support of climate change–enabling environments, and the degree to which the Bank Group diagnoses and acts on the main constraints in specific country and sector contexts.

Relevance of World Bank Group Enabling Environment for Private Sector Climate Action Country Analytical Work

The Bank Group uses country-level analytical tools to identify climate action priorities, including for EEPSCA, and the evaluation undertook a limited review of these tools. This section seeks to assess the degree to which the Bank Group’s core analytical tools are helpful in identifying constraints on private sector climate action at the country level. It does so by analyzing the first batch of CCDRs and climate-related notes associated with the FSAPs from the perspective of the EEPSCA and by using external data to assess the depth of domestic financial and capital markets for these countries. The evaluation reviewed the first 23 CCDRs and conducted a deeper assessment for 10 randomly selected reports (appendix A). This assessment was limited in scope to a desk review of the reports and related country data; it did not interview Bank Group teams or clients and did not assess the process of generating CCDRs or their impact. Consequently, this section is not intended to provide a comprehensive evaluation of these assessment tools. Rather, it assesses whether these tools emphasize the creation of an enabling environment, including the identification of barriers to private sector participation, and the availability of financing.

The first batch of CCDRs provides valuable diagnostics and actions needed to address climate change in the countries covered, including the role of the private sector. CCDRs are jointly produced by the World Bank and IFC and use state-of-the-art data, models, and tools to provide diagnostics and simulations. They help fill an important gap by providing consolidated analysis and recommendations. CCDRs use a scenario approach to explore sectoral and macroeconomic policies and investments that create synergies between climate action and short- to medium-term development objectives. In addition, they examine potential trade-offs between climate and other development objectives and options to manage them. They also explore options to manage the distributional impacts of the climate-related reform agenda. CCDRs provide estimates of the magnitude of the climate investments needed to adopt low-carbon development pathways to achieve net-zero targets (or other objectives). As the magnitude of investments is greater than public sector capabilities, all reports highlight the role of the private sector in supporting countries’ climate objectives. For most countries, the low-carbon development pathways proposed in the CCDRs are more ambitious than existing nationally determined contributions.

CCDRs lay out the long-term impact of climate change and the impact of different policy scenarios, highlighting in some cases the transition costs, but linkages with financing options for projects are less clear. CCDRs assess climate change impacts, using a macrostructural model, and a computable general equilibrium, using a standard set of variables and equations necessary for forecasting, economic policy, and budget planning analyses typically conducted by central ministries. Although they provide solid recommendations, the reports place limited emphasis on how countries can generate resources for implementing the proposed investments. Because the magnitude of annual investments proposed in the CCDRs is sizable (measured in percentage points of GDP) and because such levels are going to be required for decades, it is important to define more permanent sources of funding. The economic transitions implied by climate investment proposals may also require transition costs and the need for public sector expenditure to build safety nets for a just transition. CCDRs are only partially identifying these costs or considering how they may interact with the financing of climate action. For example, the Egypt CCDR proposes using the funds still devoted to energy subsidies after subsidy reforms (3 percent of GDP) for financing adaptation investments in cities (World Bank Group 2022c) and does not discuss funding social protection for vulnerable groups affected by subsidy cuts. However, the Argentina CCDR highlights the regressive impact of carbon tax and energy subsidy elimination (World Bank Group 2022a), unless the savings from subsidy cuts are recycled mostly through transfers to vulnerable population, which would leave limited additional resources to the government for financing adaptation investments.

CCDRs find that climate change investment needs are larger in low-income countries. The World Bank’s analysis of the first CCDRs summarizes the level of investments needed for a resilient and low-carbon pathway in 2022–30, finding that these should be 8 percent, 5.1 percent, and 1.1 percent of GDP for low-income, lower-middle-income, and upper-middle-income countries, respectively (World Bank Group 2022b). For most countries, the proposed climate-related investments (as a percent of GDP) are inverse to their per capita GHG emissions. CCDRs argue that in low-income countries, it is impossible to separate climate-related needs from development needs.

Identification of Enabling Environment Barriers

Although CCDRs provide solid diagnostics, including for needed sector investments, the enabling environments for bringing private sector investments into these sectors covered with uneven depth. For example, the Vietnam CCDR provides a comprehensive sectoral analysis and recommendations to support private sector participation in climate actions (World Bank Group 2022e). In other cases, enabling environment discussions cover only single constraint, for example, energy price regulations (Türkiye) or risk-sharing (the Philippines). The Egypt CCDR touches on some enabling issues at a high level, including price distortions, but does not identify priority actions, and instead suggests that the government should identify the priorities.

CCDRs do not sufficiently articulate the difficulty of bringing private sector capital to some of the lower-middle-income and low-income countries. For example, the CCDRs for Cameroon and the Sahel contain only vague references to mobilizing private sector capital. The challenges for bringing private sector capital to low-income countries are substantial, and it would be useful to recognize the need for reform and capacity building, including support for public sector institutional development and risk-sharing proposals that could attract the private sector. In Argentina’s CCDR, climate change enabling environment issues are not discussed, probably because enabling environment improvements would be ineffective without addressing macroeconomic imbalances, which were discussed.

Sources of Financing for Climate Action

CCDRs often do not offer proposals for financing that are consistent with the activities they envision. The sources of financing proposed in some CCDRs seem unsubstantiated and in some cases unrealistic, given countries’ financial market incentive structure, the size of their banks, and the level of development of their domestic capital markets. For the most challenging cases in the Sahel subregion, Cameroon, and Pakistan, where modeled projected investment needs for a resilient and low-carbon pathway between 2022 and 2030 are 8 percent, 9 percent, and approximately 10 percent of GDP, respectively, the discussion about financing opportunities is addressed only at a high level, including a statement about the role of the private sector. However, financing options are also not addressed in countries where investment needs are lower. For example, the Türkiye CCDR proposes annual investments equivalent to 1 percent of GDP ($8 billion) but does not propose a realistic way of financing this (World Bank Group 2022d). With an annual inflation rate above 50 percent (as of March 2023) and with a central bank interest rate of 8.5 percent, real interest rates are in deeply negative territory. In this context, private commercial banks are lending only in limited amounts and only with short-term maturities. In addition, international investors have been exiting the equity and corporate bond market. In this business environment, the government has emphasized channeling of resources to the export sector, so availability of private sector resources for investing in climate action would be limited. In the case of Vietnam, the CCDR expects the private sector to finance an annual amount equivalent to 3.4 percent of GDP, and the report suggests that Vietnam will be able to finance these investments through the creation of green bond markets. However, Vietnam’s banking system is dominated by public banks and institutional investors whose total assets are less than 10 percent of the GDP. As discussed in this chapter, the creation of a green bond market needs not simply a green tag but also a critical mass of investors willing to pay a premium for investing in assets whose use of proceeds is related to climate action. That mass of critical investors is absent in Vietnam.

CCDRs offer insufficient attention to the challenges presented to the private sector by governments’ overindebtedness and the limited development of domestic capital and financial markets. Although macro models identify governments’ indebtedness, the reports fall short in assessing the implications on financing opportunities for the private sector. As credit ratings of private sector assets have the sovereign credit rating as a ceiling, high government debt increases the cost of funding for private companies and limits the availability of funding for private sector investments. The cost of funding for projects in different countries needs to take into consideration their credit risk; for example, funding a project in Argentina is 10 times more expensive than funding it in Peru.1 Adjustments for the cost of funding may significantly increase the cost of investments needed in countries, especially if the private sector is expected to finance them. CCDRs’ implicit assumption of a homogenous cost of capital may underestimate the cost of the climate investments.

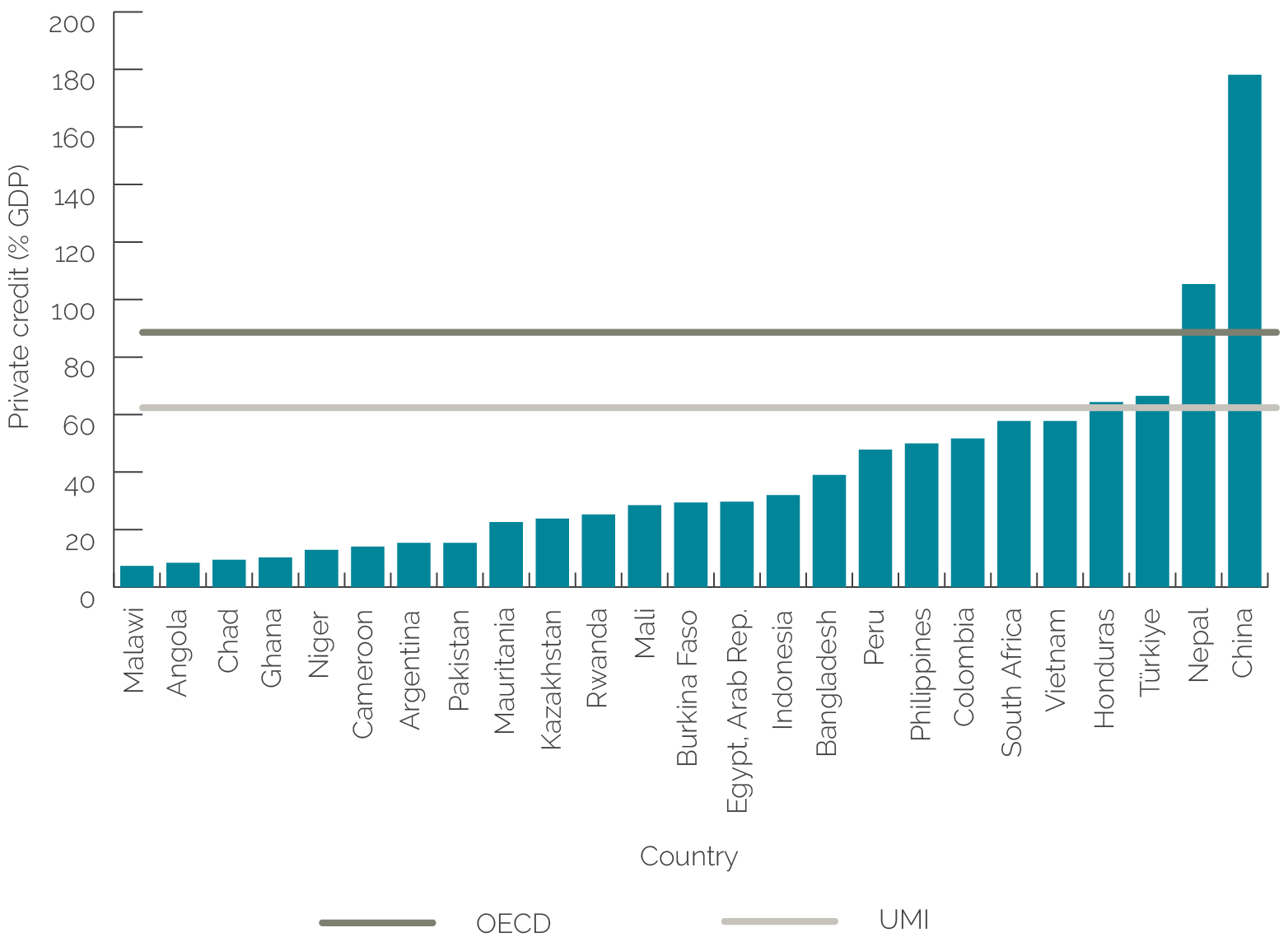

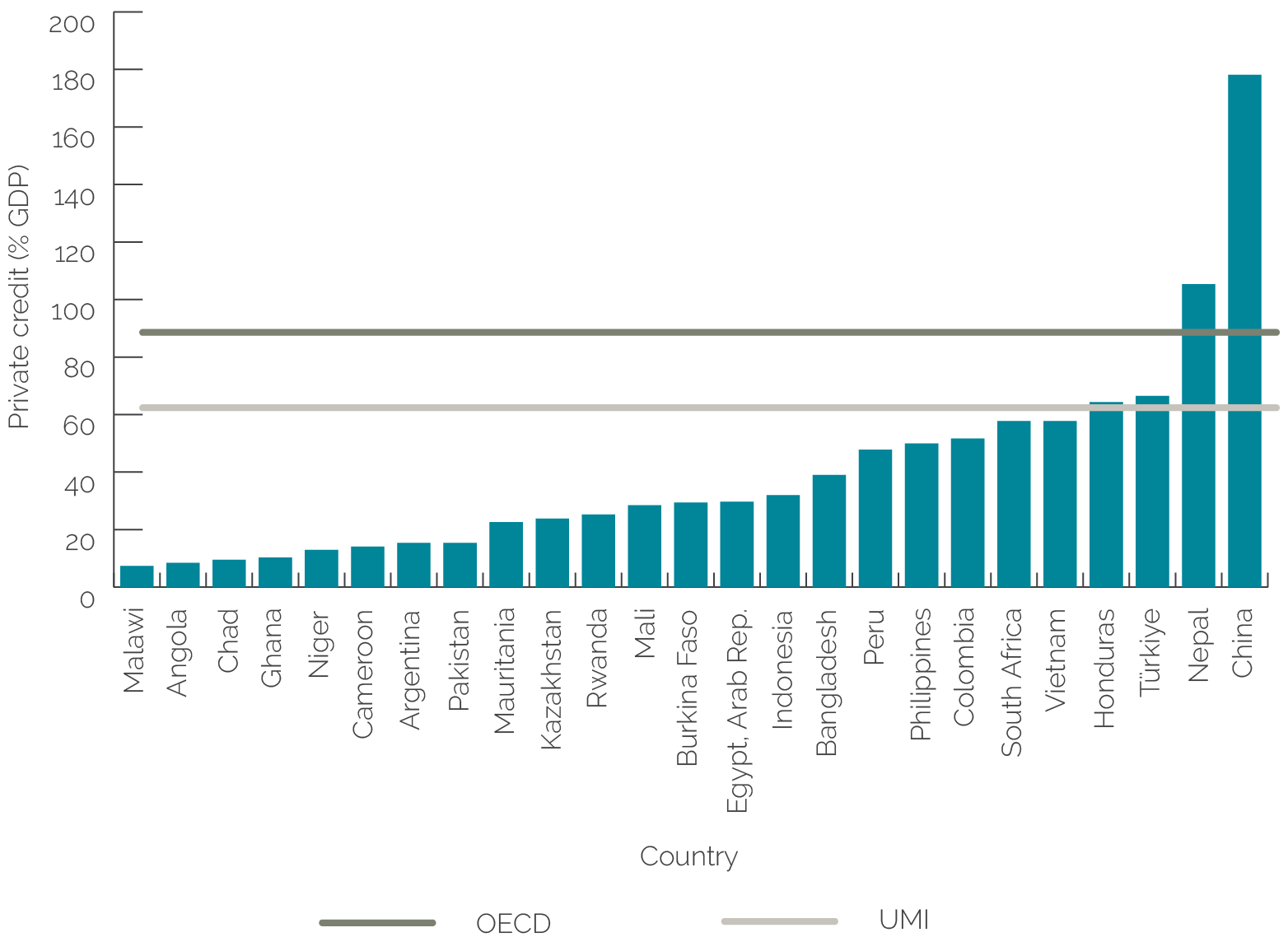

Figure 3.1. Private Credit by Deposit Money Banks and Other Financial Institutions in Country Climate and Development Report Countries in 2021

Source: Global Financial Development Database, World Bank (accessed November 2022).

Note: OECD = Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; UMI = upper-middle income.

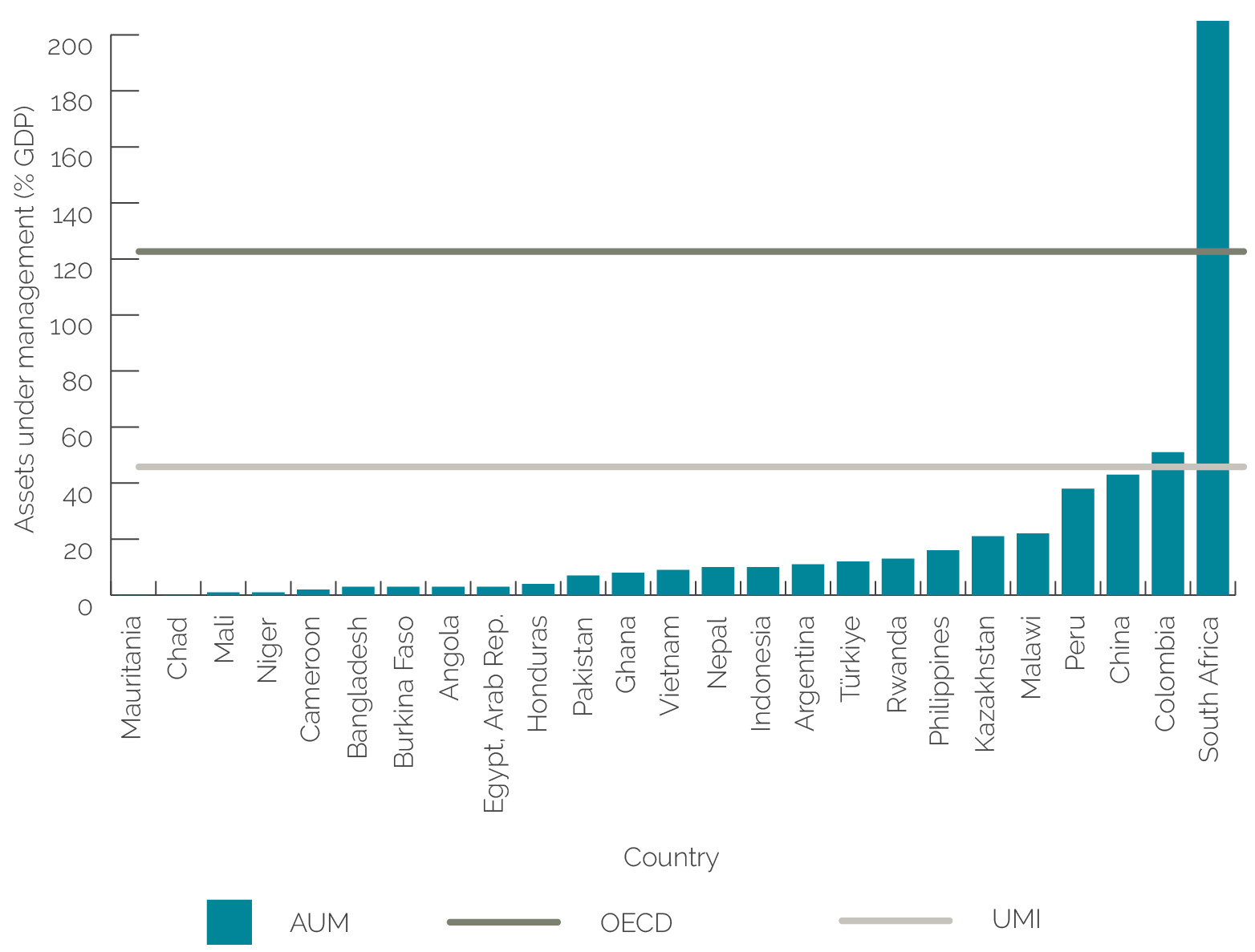

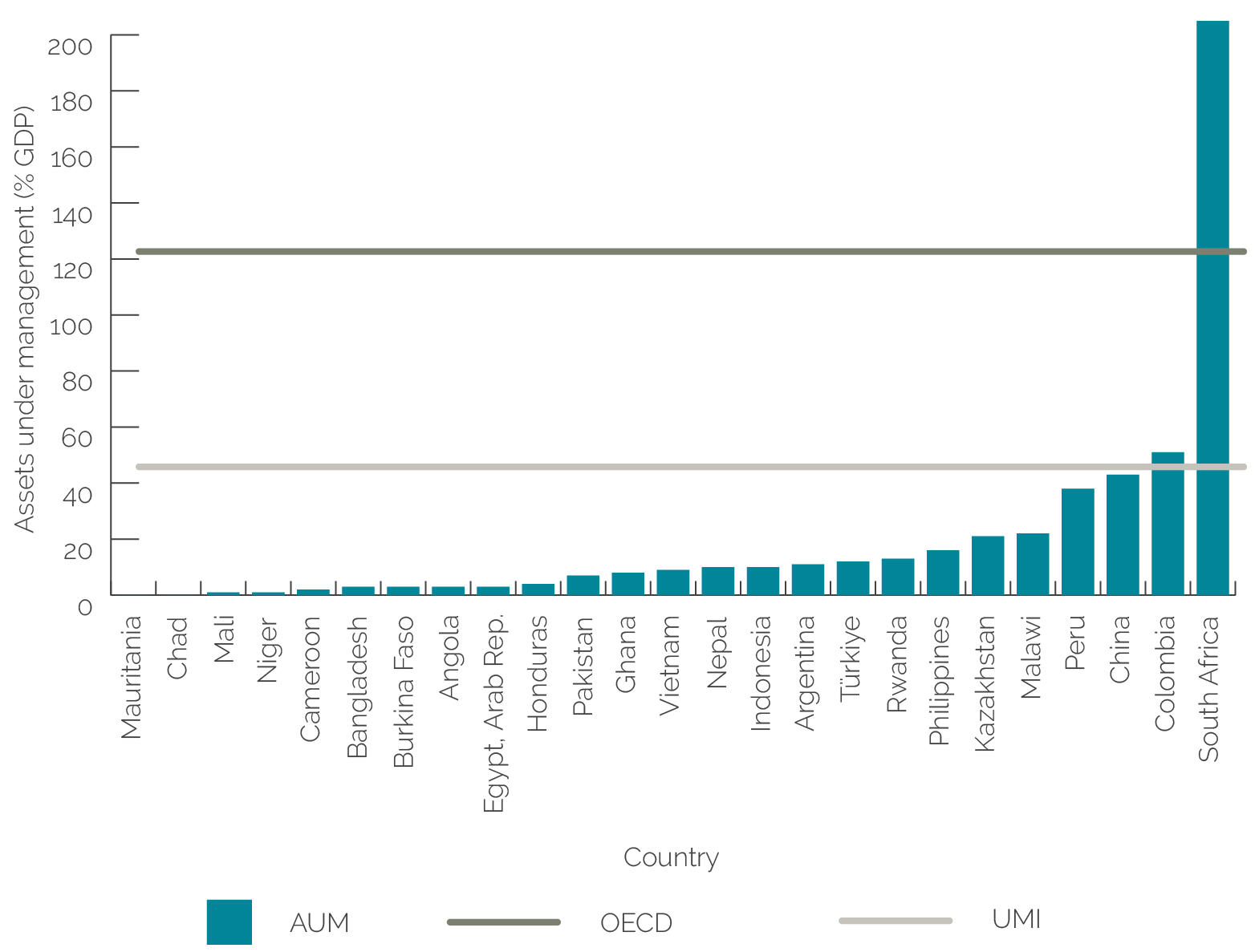

In most of the countries in the CCDR sample, domestic financial and capital markets would be insufficient to finance a significant portion of the proposed climate action agenda, but CCDRs do not include sufficient recommendations to strengthen domestic financial sectors. Commercial banks have total private sector assets of less than one-third of GDP for two-thirds of the 23 countries in the first batch of CCDRs (figure 3.1). In most countries, banks are not only small but also lack expertise in infrastructure financing (Garcia-Kilroy and Rudolph 2017; Ghersi and Sabal 2006). Assets under management by institutional investors in most countries in the sample would not be enough to provide financing for climate action products either (figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2. Assets under Management Held by Institutional Investors in Country Climate and Development Report Countries in 2021

Source: Global Financial Development Database, World Bank (accessed November 2022).

Note: AUM = assets under management; OECD = Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; UMI = upper-middle income.

Green Bond Financing

Most CCDRs encourage green and sustainable financing but do not address the limitations for these instruments, including limited market appetite for higher risk instruments. Nine of the 10 countries analyzed in depth in the first CCDRs make references to the opportunities for tapping international green bonds markets, including low-income countries and lower-middle-income countries, such as Ghana, Cameroon, and countries in the Sahel. However, domestic capital markets are little developed in these countries, and the opportunities for receiving green international financing are limited by their high government debt levels and associated poor credit ratings. Investors’ appetite for high-risk assets, either green or traditional, is low, especially in countries affected by sovereign debt distress (for example, Ghana). Most of the countries in the sample would have limited capacity to take additional foreign exchange risks, especially in the absence of foreign currency to support convertibility. Green financing does not solve the problem of currency mismatches.

Although the size of the green bond market has grown, meeting countries’ needs for climate investments would require sustained exponential expansion and a constant flow of new green investors, which may not occur. According to Cheng, Ehlers, and Packer (2022), as of June 2022, the amount outstanding on green, social, and sustainability bonds is approximately $2.9 trillion, the vast majority of which is in high-income countries. This is a small fraction compared with the size of the global fixed income market, which is approximately $127 trillion (SIFMA 2022).

In high-grade markets, green bonds offer a modest premium (greenium) compared with regular bond markets, and the appetite for low-grade instruments has been low. In 2020–22, globally corporate and sovereign green and sustainability-linked bonds are between 8 percent and 5 percent of the overall bond issuance in each category, respectively. Although some countries may still benefit from a modest reduction in the cost of financing some green projects, the depth of the green bond market does not offer the scale that is needed for financing the climate action agenda. Recent literature suggests that green bonds offer an average premium of 0.08 percent compared with conventional bonds (Caramichael and Rapp 2022), which might be insufficient to make a significant difference for the Bank Group client countries. The green bond market operates largely for high-grade issuers (with credit ratings in the range of AAA to BBB), and there is no statistically significant evidence of a premium for low-grade (with credit ratings BB to C) and not rated green bonds. In 2021, 94 percent of green and sustainability-linked bonds were issued by multilateral organizations and high-income countries (OECD 2022a) and only 2 percent were issued by lower-middle-income and low-income countries, which implies that green investors may have little appetite for low-grade green securities.

The Financial Sector Assessment Program and Other Diagnostics

Although FSAPs have not historically addressed climate change issues, they are doing so increasingly since FY19 using specific notes on climate change. The World Bank has used the established credibility of the FSAPs among ministries of finance and central banks to raise awareness of critical climate issues related to the stability of the financial sector and opportunities for climate financing. The reports offer high-quality work related to the financial stability agenda following the guidelines of the Network for Greening the Financial System (which has become the de facto standard setter).2 As of April 2023, only three climate change notes were published (for Chile, the Philippines, and South Africa), in addition to a guidance note. The notes emphasize the need to improve the quality of green financial data, support reporting and disclosures, and encourage regulators and institutions to strengthen their analytical capacity by internalizing climate risk in their models.

However, FSAP climate change notes are overemphasizing the development of green financing, while traditional financial markets have not been sufficiently developed. The reports emphasize the need to align incentives across sectors and labeling green assets for investors to identify green assets. Identification of green sectors and activities is a valuable contribution to the climate agenda. Although the FSAP notes encourage sovereign governments to get financing via green bonds, this financing is presented mostly as a substitute for traditional financing. For countries that are not regular issuers in global bond markets, issuing in segmented markets may be detrimental to traditional bond market liquidity and could affect the overall cost of funding (Hashimoto et al. 2021; World Bank and IMF 2001). Increases in the cost of funding might particularly affect low-grade credit issuers. The size of the green bond market is still a small fraction of the global bond market, and it is not evident that issuing more green bonds will be accompanied by new green investors. Proposals for tax incentives for domestic green bonds may also create further distortions.3 By segmenting the markets, countries might limit the opportunities to strengthen the traditional bond market (Hashimoto et al. 2021; IMF 2016).

Policy recommendations on financial and capital market development in other Bank Group diagnostics also do not have the level of ambition to generate private sector financing at scale. Other Bank Group diagnostic tools, including FSAPs, Infrastructure Sector Assessment Programs, and Country Private Sector Diagnostics, address issues of financial and capital market development, each with their own perspectives. However, none of them focus their recommendations on actions that could generate private sector financing at the levels envisioned in the CCDRs, such as support for domestic capital market development or increasing private sector savings. This is an important shortcoming for reports that expect to summarize the steps that countries need to take to reach their climate objectives.

Relevance of World Bank Group Enabling Environment for Private Sector Climate Action Sector Engagements

The enabling environment constraints on private sector climate action depends on specific country and sector context, which can be examined through case studies. To assess the degree to which the Bank Group diagnosed and acted on the most important constraints, the evaluation carried out 13 case studies across eight countries. These case studies considered the full set of Bank Group interventions related to a targeted private sector climate action, including analytical and advisory work, policy dialogue and awareness raising, technical assistance and capacity building, DPF, investment projects, IFC AS, and convening partners. Appendix A describes how case studies were selected and undertaken, and appendix C provides a summary of each case study.

In case studies, the Bank Group used its analytics to diagnose the most important constraints on private sector climate action. The World Bank typically uses sector-specific analytical work to identify constraints and recommend priorities, building on the knowledge of sector teams. IFC does not have a stand-alone diagnostic instrument but conducted diagnostics as part of preparing AS or drew on emerging global standard good practice in new areas, such as sustainable banking. Across the case studies, the Bank Group identified virtually all of the most significant constraints (table 3.1). For example, the World Bank conducted a substantial set of diagnostic work on efforts to induce investment in geothermal power in Indonesia. It identified constraints, including the difficulty of competing with subsidized coal power, the expensive and high-risk nature of geothermal exploration, the insufficient prices offered in power purchase agreements (PPAs), the lack of contract timeliness and predictability, challenges in environmental and social risk management and social acceptance, and a lack of sufficient public and private capacity. In Ghana, the World Bank carried out a series of sector notes and studies on constraints to reducing forest degradation in the cocoa sector, including low productivity that promotes land clearance, limited awareness and knowledge of agroforestry techniques, insecure tree tenure that discourages farmers from retaining trees, complex land tenure that disincentives conservation, limited access to credit for farm inputs, and low income for farmers inhibiting investment. In Türkiye, the World Bank’s analytics identified barriers for private investment in rooftop solar, including short-tenure contracts for feed-in tariffs that created uncertainty, a lack of subsidies to the residential sector, complex licensing, permitting and approvals procedures, a lack of technical standards, insufficient capacity and awareness of consumers, a lack of financing instruments through commercial banks, and the absence of third-party business models.

When there are constraints that are not diagnosed, these are usually relatively minor. For example, studies in Colombia identified challenges for electric mass transit systems for larger cities, which had broad integrated transport networks, but missed some issues that arose for smaller cities and towns because of a lack of economies of scale. In Honduras, the World Bank diagnosed the limited capacity of public research and development institutions as a constraint on CSA but did not support capacity building for these institutions, nor did the World Bank build the capacity of financial institutions to provide agricultural credit to producer groups.

Table 3.1. Summary of Case Study Relevance

|

Case Study |

World Bank Group Diagnosed Critical Constraints? |

World Bank Group Action on All Critical Constraints? |

|

Colombia transport sector |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Colombia sustainable banking |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Egypt, Arab Rep. energy subsidy reform |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Egypt, Arab Rep. renewable energy |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Ghana cocoa forest management |

✓ |

x |

|

Honduras climate-smart agriculture |

✓ |

? |

|

Indonesia geothermal power |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Indonesia sustainable banking |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Nepal renewable energy |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Nepal sustainable banking |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Rwanda renewable energy |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Türkiye new renewables |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Türkiye energy efficiency |

? |

? |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: These are all simplifications of complex situations. ✓ (check mark) = largely successful; ? (question mark) = mixed success; x = unsuccessful.

In only a few cases, important issues were not diagnosed in part because they did not naturally align with sectoral interventions. For example, in Türkiye, efforts to promote energy service company (ESCO) models had limited success in part because of an absence of commercial insurance products that would mitigate cash flow risks, credit default risk, or construction risk, leaving the ESCOs to bear the full risks or purchase expensive international insurance in foreign currency. This curtailed the willingness of private banks to lend to ESCOs. The World Bank’s work on ESCOs had concentrated on more technical constraints within the energy sector. IFC’s efforts to promote green buildings in Türkiye were also not well aligned. The main barriers in the energy performance certification process were the low technical capacity of auditors and insufficient data collection, monitoring, and verification, which were not identified in IFC’s green building project note; instead, the project was designed to promote IFC’s own green building certification and acquire market share.

Whereas some enabling environment constraints can be addressed by technical solutions, others involve trade-offs that may face political economy barriers. Literature on political economy emphasizes two perspectives: a rational choice perspective and a power-based perspective (World Bank 2008). Opposition to reforms may come because actors disagree on the potential effects of those reforms or how those effects should be valued, or they may come because groups with power see their economic or political interests threatened by the reform. The political economy barriers to EEPSCA reforms observed in this evaluation are consistent with these perspectives. The evaluation observed three main types of barriers. First, governments may have concerns about the negative effects of proposed policy changes on some groups. For example, governments may be reluctant to adopt energy tariff increases, carbon taxes, or fossil fuel subsidy cuts because they are concerned that these policies may increase costs to industries and households. Second, some governments are uneasy about private sector development because they believe private companies may not maximize the public good and might increase prices, reduce service quality, or shift profits offshore. In interviews, Bank Group staff argued that some governments were concerned about private sector growth creating alternative sources of power that they would not control. Third, there can be resistance to institutional reform from key state or private sector actors who may see reforms that shift activity to the private sector as weakening their power or reducing their profits or market share.

Politically informed policy reforms can sometimes ameliorate political economy barriers. Literature on political economy suggests several strategies for politically informed policy response (Fritz, Levy, and Ort 2014). Politically responsive policy design can involve alleviating concerns about negative effects by introducing parallel policies to mitigate their effects, such as combining subsidy reform programs with social programs to support the poorest people. It can also involve engaging in reform options preferred by local stakeholders even if these contravene best practices, such as incremental approaches that build private sector participation more gradually. Enhancing information on policies and options can lessen stakeholder opposition. Multistakeholder engagement can include intensive outreach to decision makers and stakeholders, seeking to build support for reforms. However, some political economy barriers may remain intractable until the political context changes.

The Bank Group usually engaged on constraints that can be addressed by technical solutions that did not face political economy barriers. Evidence-based policy dialogue with government leaders and senior civil servants often created opportunities for the World Bank to engage on enabling environment reforms or improvements. The World Bank and IFC were highly valued by client governments for their technical advice, credibility, and ability to introduce global knowledge. The Bank Group was often able to bring technical solutions to bear, such as new financing facilities, advice on legal frameworks, information sharing, awareness raising, and capacity building. Although the World Bank in Indonesia engaged with the government in the development of risk-sharing mechanisms to mitigate geothermal exploration risk, its engagements on policy discussions regarding fossil fuel subsidies were limited. The World Bank understood that it did not have the influence to tackle the issue directly without jeopardizing its relationship with the government; thus, it limited its engagement on subsidies to its diagnostic work and policy dialogue rather than pressing for subsidy reform as a prior action for its numerous DPF operations. In Türkiye, the World Bank worked through the Partnership for Market Readiness to conduct studies on technical aspects for the creation of an emissions trading program, such as designing and piloting a monitoring, reporting, and verification program, but the World Bank has not yet engaged on more politically challenging issues, such as determining the rules for allocations of permits.

When the Bank Group does not engage, it is usually because the constraint is a higher-level issue or has significant political economy challenges or because client buy-in or ownership is lacking. The World Bank can seek to persuade and to influence, but as a demand-driven institution, it is rightly constrained by the willingness of client governments to adopt reforms. In Ghana, although the World Bank had diagnosed constraints to better forest management in the cocoa sector since 2014, the World Bank was not able to translate these into actions because it was unable to find a successful strategy to address political economy challenges. For many years, the World Bank was not able to reach an agreement on a lending project in the sector because (i) the main cocoa parastatal lacked trust in the World Bank (in part because it believed previous World Bank–recommended policies were unsuccessful); (ii) it has found difficulty in persuading stakeholders on the need for institutional reform or in addressing sensitive topics, such as land and tree tenure; and (iii) the government has been reluctant to borrow for the cocoa sector on International Development Association and International Bank for Reconstruction and Development blend terms. As of March 2023, a lending project is in preparation on International Development Association terms but has not yet been approved.

The Bank Group has sometimes been able to engage on politically sensitive issues, including as a consequence of crises. A fiscal crisis in Egypt in 2014 meant that the government faced extreme pressure to reduce government spending. This opened an opportunity for the World Bank to engage on reducing fossil fuel subsidies, in coordination with IFC and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency activities on renewable energy. This effort was successful, leading to a reduction of energy subsidies equivalent to 7 percentage points of GDP between 2014 and 2017. The subsidy reduction also increased the credibility of government contracts with the private sector for renewable energy.

In a few cases, some key constraints were beyond the Bank Group’s capacity to engage at that time. In some countries, creating an enabling environment required a series of interventions at different levels. In some cases, technical teams found difficulty in engaging in some of these discussions with stakeholders, including on the role of the private sector in the economy or the importance of market base interest rates in fostering involvement of the financial sector for financing investment projects. Political instability in Nepal had been the main barrier to the development of the hydropower sector. Only after the establishment of a new government in 2018, following adoption of a new constitution, and after urgent power shortages were addressed, was the World Bank able to get traction on institutional and policy reform in the power sector. In Türkiye, some of the main barriers to energy efficiency investments were volatility in energy prices and macroeconomic instability, which were not feasible to address with World Bank projects at the time and would require broad structural reforms.

The Bank Group has been able to accommodate its interventions to policy boundaries imposed by governments, including limitations in the role that they see for the private sector in supporting the economy. In several client countries, governments or key institutions are skeptical about private sector approaches. This has meant that the World Bank sometimes needed to make compromises in its engagement. In Rwanda, for example, the World Bank supported efforts to improve energy access by creating subsidized financing mechanisms for off-grid solar systems. The World Bank’s technical analysis suggested that this was most likely to be successful if subsidized finance could be channeled directly to medium-size companies, but the government preferred to work through state-controlled credit cooperatives, even though these lacked the technical capacity to manage a pipeline of off-grid power projects. The World Bank approached this dilemma by approving a project that contained funding windows for both approaches but postponing the opening of the private sector window. After two years of operation, and the facility reaching only 1 percent of its target for new connections, the government allowed the use of the private sector window. The new window was highly successful—265,067 off-grid solar connections were made over 2020–22 (89 percent of them through the private sector window). This strategy brought some risks, in that the World Bank had approved a project that it knew was unlikely to succeed in the original form. Reaching success required flexibility and an understanding of the benefits of building long-term engagements with client countries.

In most cases, engaging substantially on enabling environment barriers required use of lending and nonlending instruments. In several cases, the Bank Group brought to bear the full set of its instruments, including nonlending diagnostics and technical assistance, investments, and policy lending. This was the case in the energy sector in Egypt, Indonesia, Nepal, and Rwanda and in the transport sector in Colombia. In a few cases, the World Bank was able to have a significant impact solely through nonlending work, but this was usually because of the influence and credibility gained from previous engagements. For example, the World Bank played an influential role in enabling environment improvements for emerging renewable energy technologies in Türkiye using only analytical work, technical assistance, and policy dialogue, but this was possible because of the trust and reputation built from its intensive prior energy engagements, supporting the liberalization of the energy sector and substantial investments, and because the World Bank took a demand-driven approach that responded and adapted to government priorities. In other cases, engagement was more limited; the World Bank sought to bring CSA practices to smallholder farmers in Honduras by building these practices into a long-running matching grant program for small farmers through productive alliances and was not able to use this as a platform for significant policy dialogue or reform in the agricultural sector. As discussed, in Ghana, the inability to develop a lending project constrained the World Bank’s ability to influence the enabling environment.

Although the evaluation did not analyze Bank Group interinstitutional coordination in detail, evidence suggests strong collaboration in renewable energy but little collaboration for climate-related PPP activities. World Bank–IFC collaboration on renewable energy was relatively strong. Out of the 18 IFC EEPSCA AS activities for renewable energy, 13 were performed during the same period that the World Bank was providing EEPSCA analytics or AS. For example, in Zambia, whereas the World Bank provided AS on solar and wind resource measurement and mapping, IFC supported transaction AS for solar generation power. For climate-related PPPs, there was no overlap between the countries where IFC AS and World Bank nonlending projects were conducted (except for some cases of regional activities), suggesting little coordination between World Bank support for upstream PPP reform and IFC PPP transaction advisory.4 This finding suggests some missing opportunities for collaboration. IFC interventions targeted several low- and middle-income countries, whereas World Bank nonlending activities had only a single intervention in a low-income country.

The Bank Group was often able to usefully combine upstream policy changes with midstream activities. Although high-level policy settings are important, sometimes they need to be complemented by activities to build project pipelines. In Türkiye, while upstream policies were important in establishing incentives, many barriers to new renewable energy investment were midstream issues, such as raising awareness, mitigating risk, creating business models, improving access to finance, and addressing complex procedures. In the case of Egypt, the Bank Group was able to engage in upstream policy reforms that helped stabilize the fiscal framework, including reductions in fossil fuel subsidies for an annual amount equivalent to 7 percent of GDP. In a context where the government did not have the financial strength to honor their contracts with private sector partners in the gas industry, Bank Group interventions aimed at allowing competitive bidding, net metering, and a system of feed-in tariffs helped the country in building credibility for attracting private sector investments in renewable energy. The reductions in fossil fuel subsidies were key for signaling to private investors the government’s intentions of creating a competitive market of renewable energy in relation to nonrenewable ones. In the case of Colombia, the Bank Group engagements related to the PPP framework have paved the way for engagements with subnational governments in urban transport, more specifically in electric mass transport operations.

Bank Group–supported approaches have frequently applied incentive policies (“carrots”) for emission-reducing or adaptive behaviors but rarely applied penalties or costs (“sticks”) to GHG-emitting or maladaptive activities. Many client countries find it difficult to impose or enforce penalties (or taxes) and are more comfortable with positive incentives, which may be more politically realistic. For example, in Türkiye, the World Bank’s engagement emphasized positive incentives, such as a new risk-sharing facility for geothermal exploration, designing new financial products for rooftop solar, and support for tradable emissions permits (where firms are initially allocated permits) rather than carbon taxes. This was aligned with the broad approach applied by the government; legislation often includes both incentives and penalties to induce behavioral change or compliance, but penalties are rarely implemented or are frequently pardoned, so penalties have little enforcement power. Globally, the introduction of direct carbon pricing has been infrequent not only among World Bank lending activities but also among Bank Group client countries. One of the few examples of sticks in the case studies was in Colombia. Bank Group nonlending work contributed to the continuation and expansion of taxes on dirty fuels (although this was in the context of several carbon tax measures enacted independently by the government), and Bank Group technical work contributed to congestion pricing. Another example was the reduction of energy subsidies in Egypt. There are also risks of taking stick policy actions that in practice are ineffective. As documented in the World Bank’s State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2023, the introduction of carbon taxes on gasoline in Uruguay was in practice a rebase of the previous gasoline excise tax, without any change in relative prices to final users. However, if countries find it difficult to meet their emission reduction targets, they may have to rely more on taxes, bans, or mandates.

- This calculation is based on the sovereign cost of funding for Peru and Argentina in international markets, based on data from March 2023.

- Some Financial Sector Assessment Programs also cover other climate-related issues, including vulnerabilities to climate-related and environmental risks; supervisory response and guidance; deepening green finance markets; deepening markets for climate risk resilience; and greening of development finance institutions. However, designing a path to finance countries’ climate agenda is beyond the scope of the Financial Sector Assessment Programs.

- Tax incentives for domestic green bonds would interfere with the deferred taxation approach used for many large institutional investors, such as pension funds. It would deter these investors from purchasing green bonds, leaving only retail investors to purchase these assets. Tax incentives would also shift the cost of a greenium to taxpayers, and the distorted market may mean that this greenium is captured by intermediaries rather than investors.

- International Finance Corporation public-private partnership advisory services involve support to governments in preparing, structuring, and implementing a transaction (for example, of a solar power plant) through to a tender process. These services include advice on project selection, project preparation, bidder prequalification, request for proposals, financial close, and contract management.