Financial Inclusion

Chapter 3 | Effectiveness of World Bank Group Engagement in Financial Inclusion—Doing Things Right

Highlights

This chapter complements chapter 2 (which examines whether the World Bank Group is doing the right things) by assessing the Bank Group’s effectiveness on financial inclusion (that is, whether the Bank Group is doing things right).

What the Bank Group does most often to support financial inclusion is not always what it does best. Improving access and strengthening institutions were the most frequent financial inclusion objectives but were not the most successful. Projects with explicit consumer protection and financial literacy objectives were successful but uncommon. Bank Group support aimed at reaching or empowering excluded groups was rare and less often successful compared with support to achieve other objectives.

National financial inclusion strategies often provided adequate analysis, guidance, and governance mechanisms for countries to enhance financial inclusion. However, they were not always as comprehensive or as targeted as envisioned.

Bank Group institutions used different instruments for different purposes with varying success. International Finance Corporation investments in credit underscore both successes and challenges in finding viable business models to deliver services to microenterprises, poor households, women, and other excluded groups. World Bank development policy operations supporting credit had a 77 percent success rate. Development policy operations also supported policy, regulatory, and institutional reforms that often expanded service delivery. Development policy operations, investment project financing, and International Finance Corporation advisory services supported payments, mostly successfully.

Although the emphasis on digital services grew, World Bank projects focused on digital delivery had a 72 percent success rate. The International Finance Corporation was equally successful with digital and traditional services (77 percent) and relatively more successful with projects using both (86 percent). Sometimes well-placed technical assistance projects appeared to bring major benefits.

Evidence on outcomes is weak, making it difficult to attribute observed improvements in outcomes to Bank Group activities.

This chapter addresses the effectiveness of the Bank Group’s engagement in financial inclusion. First, it examines the effectiveness of the Bank Group’s support for financial inclusion by objective.1 Second, it discusses the Bank Group’s upstream engagement in policy, legal and regulatory reform, and institutional development. It then looks at success in delivering financial services by traditional and digital means.

Effectiveness by Objective

Improving access and strengthening institutions—the most frequent project objectives—were fairly successful. As noted in chapter 2, early in the evaluation period, access was a primary concern of client countries and the Bank Group. Although objectives diversified, the COVID-19 response renewed emphasis on the quantitative targets for people with accounts (box 3.1). Projects supporting access objectives showed an average success rate of 77 percent. Projects aimed at strengthening institutions showed an average success rate of 81 percent. Other, relatively rarer, project objectives were associated with higher rates of success—consumer protection (90 percent), financial literacy (87 percent), and stability (85 percent).

Box 3.1. Pakistan: Increasing Access during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Before the pandemic, the World Bank supported the government of Pakistan in expanding the Benazir Income Support Programme through two development policy operations (P147557 and P151620). Following the onset of the pandemic, the World Bank supported the expansion of the program to channel additional support to its 4.5 million women beneficiaries. The World Bank also supported emergency cash transfers under the Ehsaas Kafaalat Programme, using digital channels to include an additional 7.5 million vulnerable families through the active Crisis-Resilient Social Protection program (P174484). Pakistan made government-to-person transfers for existing social transfer beneficiaries into single-purpose accounts configured only to receive payments from the government.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group Pakistan case study.

IFC AS projects with an access objective were successful an average of 82 percent of the time. They were more frequently successful than IFC investments with the same objective (68 percent average success rate). For example, in the Dominican Republic, IFC AS–supported Asociación La Nacional de Ahorros y Préstamos strengthened its risk management and corporate governance practices. The aim was to serve the low-income housing and SME markets better and prepare for transformation into a commercial bank. However, an IFC AS project in Morocco (one of the 18 percent of projects that were not successful) that intended to help a local MFI transform into a regulated, commercially oriented NBFI did not achieve its objective because an enabling central bank regulation was not issued.

IFC often aimed to help client financial institutions transform their institutional structure to a commercial one to enable them to grow their client base, diversify their product offering, and enhance their long-term sustainability while maintaining focus on underserved groups. IFC projects that supported transformations were more frequently successful than projects that did not (81 percent compared with 64 percent average success rate). IFC supported transformations of NBFIs and MFIs in many cases with the use of advisory projects (box 3.2). The intended outcomes included improvements in the availability, cost, and quality of financial services, strengthening of the capacity of financial intermediaries, improvements in the market function, and improved outcomes regarding access and usage of financial services by formerly excluded groups and individuals. Through transformation support, clients were able to expand their product offering through savings (70 percent), housing finance (46 percent), agribusiness finance (30 percent), and insurance (30 percent).

DPOs with the access objective were successful an average of 80 percent of the time, and World Bank investment projects were similarly successful. A DPL in Uruguay successfully supported the government in developing and implementing policies to increase access to financial services for poor people by introducing fiscal incentives for installing electronic points of sale in small businesses, facilitating electronic payments. The number of points of sale increased by more than three times, far exceeding project targets and facilitating tremendous growth in digital transactions. The government used this network to deliver digitized payments during COVID-19.2

Box 3.2. International Finance Corporation Support for Clients’ Transformations

In India, the International Finance Corporation took a programmatic approach that aimed to support microfinance institutions through a large umbrella advisory services project that supported institutional transformation by providing long-term, comprehensive, and integrated investment and advisory services. In addition, the International Finance Corporation successfully supported the transformation of four nonbank financial institutions with long-term financing and two with advisory services projects that provided them with a strategic plan, savings mobilization, a diversified range of services, enhanced information technology systems, or strengthened corporate governance. In two of those cases, the nonbank financial institutions were able to lower their lending costs while maintaining their customer profile.

In Nigeria, the International Finance Corporation supported two local microfinance institutions to transform into deposit-taking microfinance banks. They grew faster than the rest of the banking system and were able to offer new services while maintaining their focus on low-income and women clients. There was a replication benefit for the Nigerian microfinance sector—subsequently, seven additional microfinance institutions obtained a national microfinance bank license.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Although infrequent, IFC AS and World Bank ASA were used to support consumer protection and financial literacy objectives. Because financial inclusion aims at reaching financially excluded populations through a wide array of providers, many countries are facing the need to protect new users from unethical practices (consumer protection) and educate them on how best to benefit from such services (financial literacy). Only 4 percent of evaluated financial inclusion projects had financial literacy objectives, with an 87 percent average success rate; 5 percent of projects had consumer protection objectives with an average success rate of 90 percent. Financial literacy and consumer protection remain key constraints in most case study countries, with a need to protect and inform new and potential users. For example, in Tanzania, IFC successfully facilitated a nationwide marketing campaign targeting one million people to increase the number of interoperable person-to-person payment transactions.

The World Bank supported consumer protection and financial literacy by working mostly upstream through regulators, public agencies, and service providers. The World Bank began supporting Egypt in strengthening financial consumer protection in 2017, financing ASA within the framework of the Financial Inclusion Global Initiative. With this support, the central bank and financial regulatory authority of Egypt updated the regulatory framework to include consumer protection, with provisions on disclosure requirements, fair treatment, complaint handling, and dispute resolution. The central bank also introduced an ombudsman within a new consumer protection department.

IFC engaged on financial literacy downstream by delivering training directly to consumers. For example, in Brazil, IFC advisory used a $1.1 million grant to educate low-income customers through mass marketing programs and a mobile money supplier. It reached its targeted number of active users, new users, noncash transactions, and accounts linked to mobile banking systems. In Kenya, IFC AS included training farmers in financial literacy and training 350 promoter farmers, who in turn trained farmers in 12 cooperative societies.

Bank Group support with explicit objectives of reaching or empowering excluded groups was rare and had a 69 percent average success rate. There were only 11 such projects among 293 evaluated projects. Some IFC AS projects used modest funding to achieve success. In the Philippines, IFC AS supported the Center for Agriculture and Rural Development to develop and launch fintech solutions for its rural base of microbusinesses and low-income customers, composed largely of women. The center introduced new risk management procedures and standards and transmitted improved practices to its clients through workshops and other means. Some World Bank investment projects also succeeded in enhancing the enabling environment for excluded groups. In Armenia, the World Bank supported activities to enhance internet access and improve consumer trust and security through the digital citizen program (which created a national certification authority for issuing electronic signatures) and digital literacy through the Computer for All program.

Support of Policies and Institutional Development

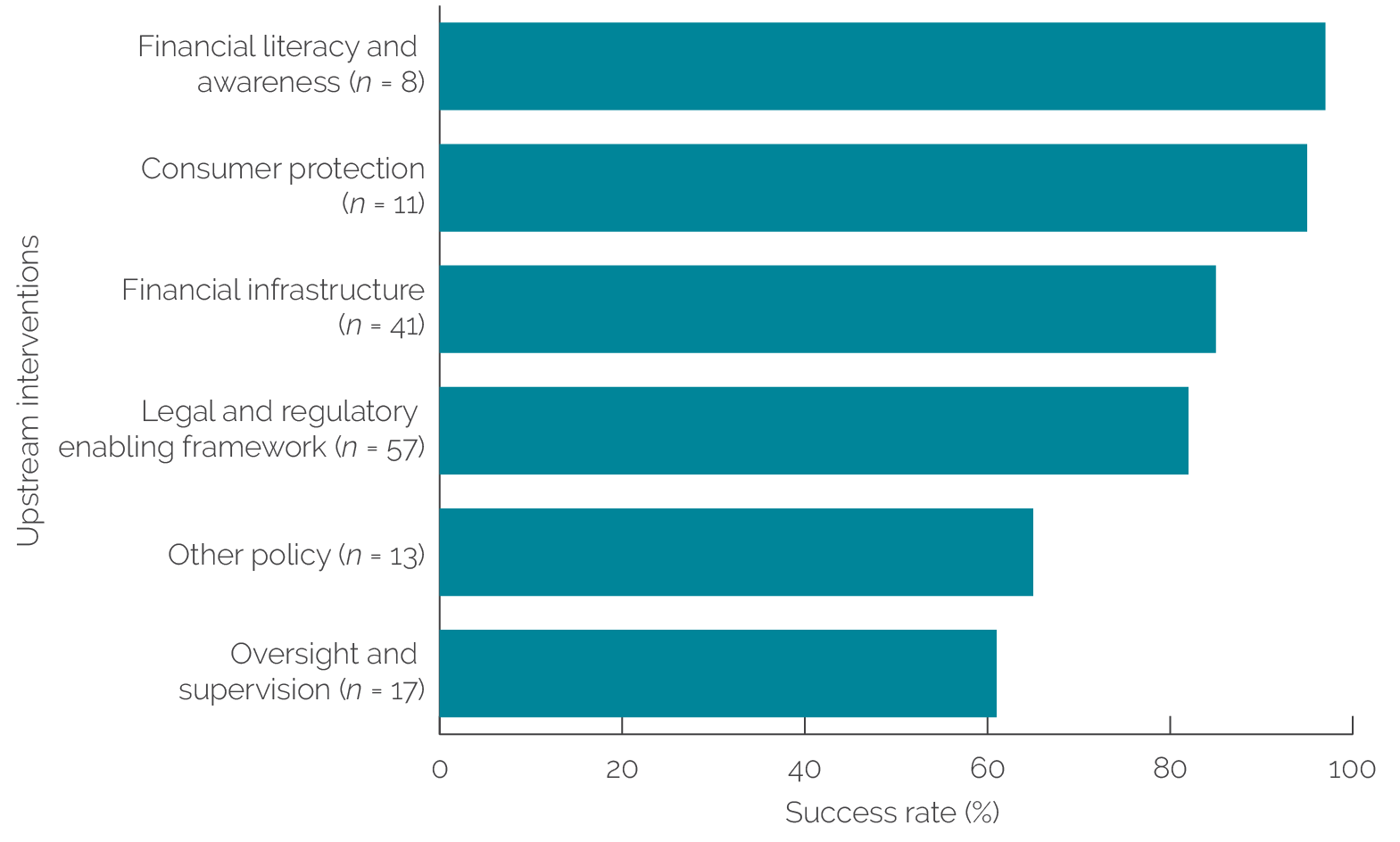

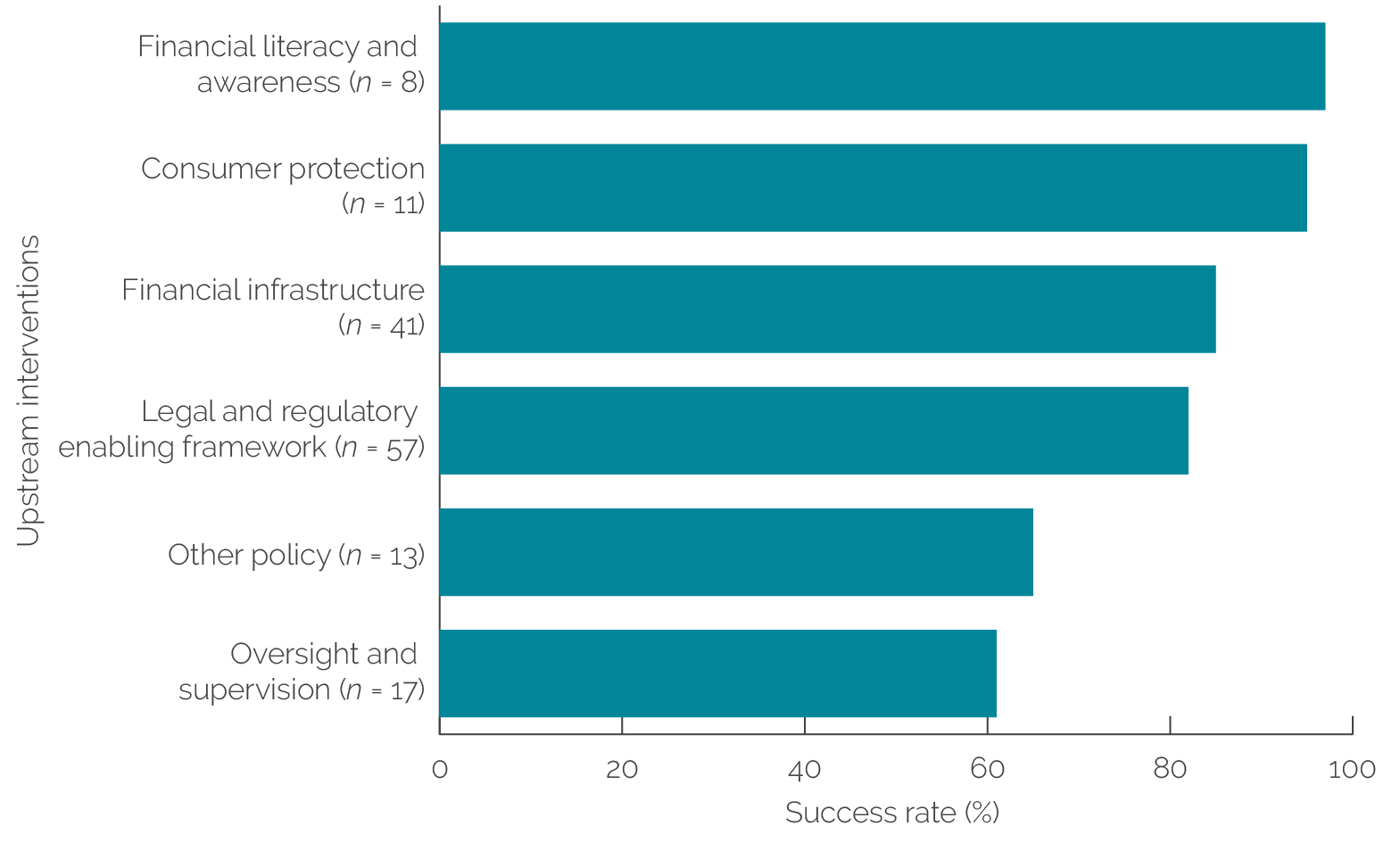

The Bank Group often engaged with governments on upstream policy, regulatory, and institutional reforms related to financial inclusion. These engagements included support for developing NFISs, establishing legal and regulatory enabling frameworks, strengthening financial infrastructure, and enhancing oversight and supervision. Development of NFISs was a key entry point for Bank Group support. The most frequent type of upstream Bank Group support was for reforming laws and regulations, such as reviewing financial inclusion regulatory frameworks, developing and introducing regulatory frameworks for mobile banking and payments, and establishing comprehensive policy and regulatory frameworks for payment systems. This type of support had an 82 percent average success rate (figure 3.1). The Bank Group strengthened oversight and supervision with a 61 percent average success rate through, for example, developing the capacity and independence of national supervisory bodies, carrying out organizational separations between oversight and operational functions, and establishing payment oversight functions.

Figure 3.1. Project Success Rate by Upstream Objective

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio review and analysis of evaluated projects.

Note: The number of projects with each type of upstream objective is shown in parentheses.

Projects supporting strengthening financial infrastructure were mostly successful. Bank Group support to financial infrastructure had an 85 percent average success rate. Although IFC investment services did not support financial infrastructure, IFC AS support had an average success rate of 90 percent in projects aiming to strengthen financial infrastructure. World Bank financing projects (policy and investment) supporting financial infrastructure had an average success rate of 81 percent. Both IFC and the World Bank sometimes aimed their support for financial infrastructure at reducing information asymmetries between lenders and borrowers and enabling the safe and efficient transfer of money between individuals, firms, and governments.

Most of the evidence of the effectiveness of support to financial infrastructure concerns the creation, strengthening, and coverage of credit bureau systems, credit information reporting systems, collateral registries (movable or immovable), security registries, and, more recently, payment systems. For example, IFC AS support has been effective at implementing or strengthening credit bureau systems (in Haiti and Tanzania), collateral and security registries (in Liberia, Malawi, Nigeria, and Bhutan), and credit reporting systems (in Tanzania and Vietnam). A World Bank investment lending project in Guinea successfully supported improvements to the credit information and reporting systems and the modernization of the payment system at the central bank.

The Bank Group was less successful in enhancing financial infrastructure when the underlying constraint was the legal and regulatory framework. In Bhutan, IFC AS capacity building could not occur because of delays in reviewing a draft law. Tunisia did not achieve a DPL prior action supporting an increase in licensed private credit bureaus because the parliament did not approve a draft credit bureau licensing law. This type of support often lacks evidence of reaching excluded populations. For example, the World Bank supported Bhutan to expand its credit bureau coverage, but the broad monitoring indicator did not show whether it served target groups. Similarly, although IFC AS successfully supported Haiti in introducing a credit bureau, it was unclear whether it reached the target market of MSMEs or whether its reporting system was operating properly for such clients.

DPOs were effective in supporting policies that required focused, short-term interventions but less well suited to support reforms that needed longer gestation efforts. In the Philippines, DPLs proved useful to sequence and anchor important policy actions. However, they were not well suited to support longer gestation efforts, such as financial and digital literacy, that are essential for financial inclusion. In Brazil, there was little evidence of achievements of DPLs focused on providing access to rural producers and SMEs. Indonesia exemplifies a sophisticated client to which the World Bank committed a large volume of DPLs over the evaluation period. However, the projects lacked practical methods to gauge details of financial inclusion progress and, alone, were insufficient to move development indicators.

Success in the Delivery of Financial Services

Credit, Savings, Payments, and Insurance

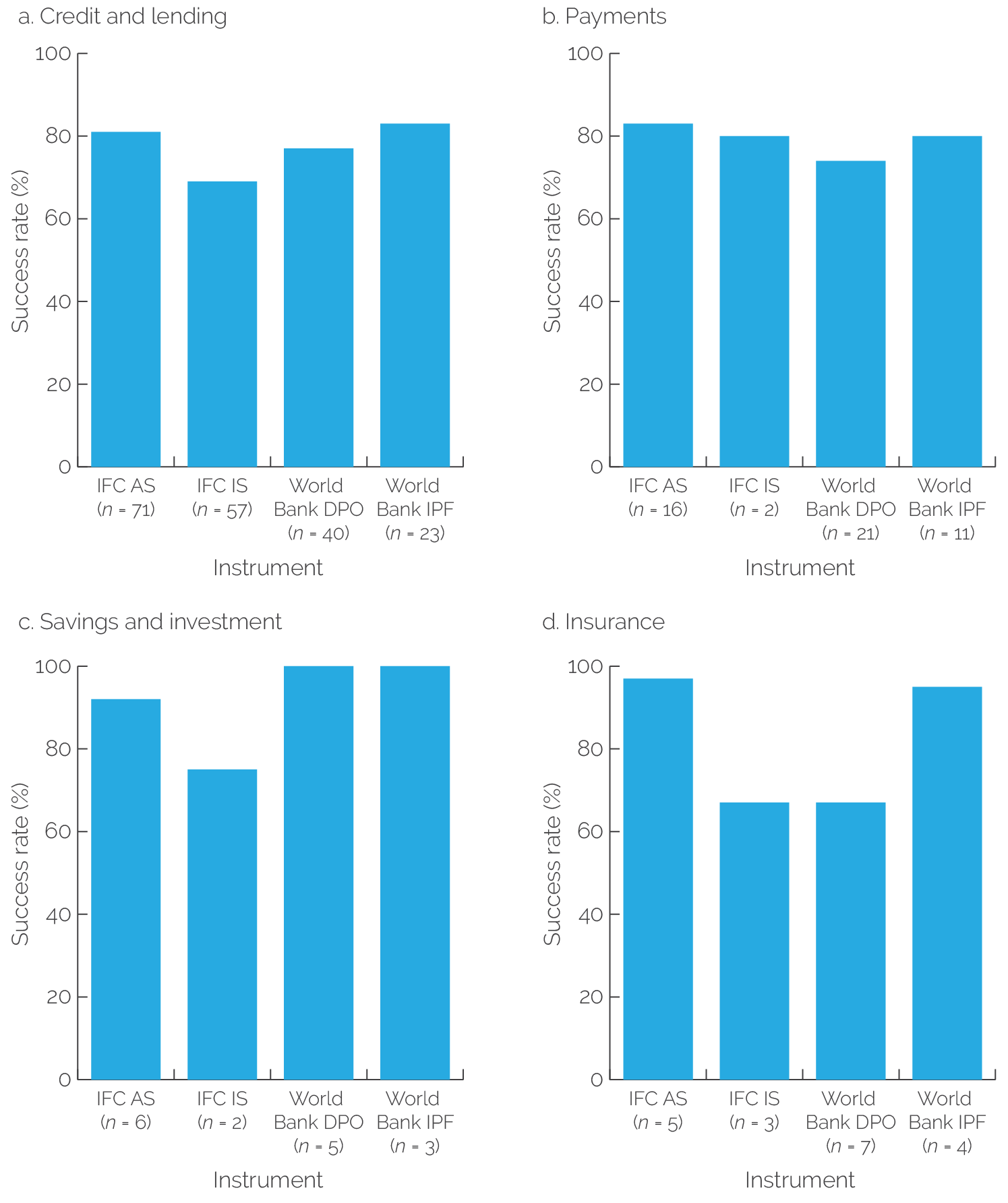

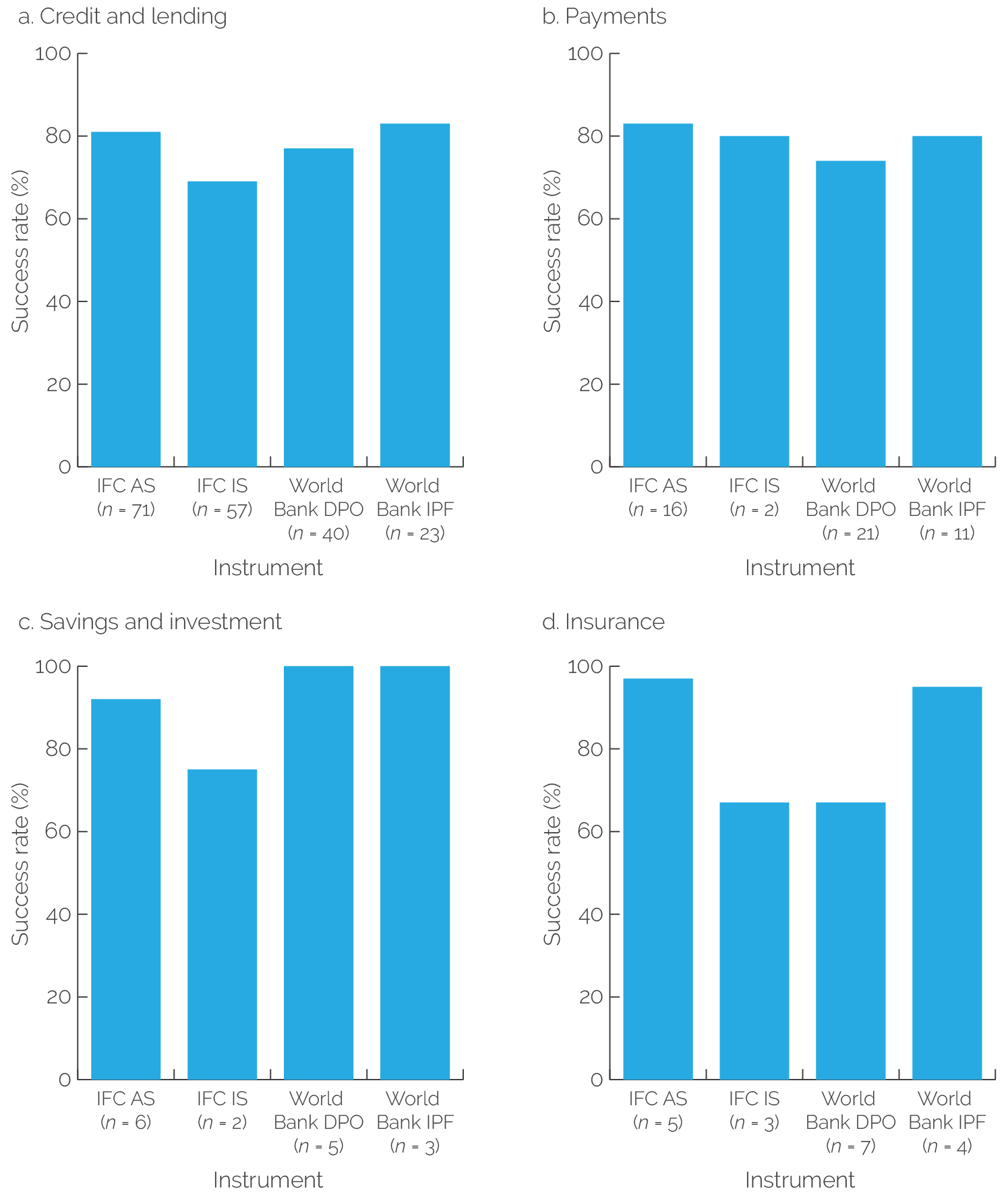

The Bank Group’s support for financial services to underserved groups, which mainly concentrated on credit, had mixed results. Credit was more frequently supported than other services, whereas support for savings and investment was relatively rare. Success rates varied both by service and instrument (figure 3.2). DPOs were more successful in supporting savings services than in supporting payment services, whereas IFC AS were highly successful in supporting insurance.

IFC investments faced both successes and challenges when providing credit support to underserved groups. Support for financial services with the objective of providing access to credit included 93 percent of the evaluated IFC investment portfolio, with an average success rate of 69 percent. A key challenge was finding sustainable business models for delivering financial services to MPWEG (box 3.3).3 One successful IFC investment supported a senior-term loan to a leading MFI in West Bank and Gaza. The investment aimed to finance the MFI to support its microfinance activities and expand its outreach. At evaluation, the MFI increased its loan portfolio about four and a half times and surpassed its target number of borrowers. However, in Nigeria, IFC’s support for a commercially oriented MFI to provide a full range of financial services to MSMEs and low-income populations met less success. The client reached less than 40 percent of its target for microloans and less than 20 percent of its target for active borrowers, and missed its volume targets for microfinance and women entrepreneurs.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio review and analysis of evaluated projects.

Note: The number of evaluated projects within each service and instrument is shown in parentheses. AS = advisory services; DPO = development policy operation; IFC = International Finance Corporation; IPF = investment project financing; IS = investment services.

Box 3.3. Finding Sustainable Business Models for Microenterprises, Poor Households, Women, and Other Excluded Groups

Support for private engagement in financial inclusion found only a few sustainable business models for extending financial services to poor people. Beyond credit, services, such as microsavings and microinsurance, which have proven more beneficial to low-income individuals in the literature, are not associated with profits when offered as stand-alone businesses. Some microcredit and mobile money services have proved financially sustainable. However, the COVID-19 pandemic posed substantial challenges for many traditional microfinance institutions. Most models for delivering financial services to the underserved and excluded required an element of subsidy.

- In Tanzania, the government had realized by 2014 that the low density of its rural population made it unprofitable for the private financial sector to serve remote areas. It emphasized mobile money accounts, and access grew rapidly. However, this growth did not always reduce gender or rural gaps. That required deliberate targeting, for example, by enhancing mobile reach to women and improving rural internet connectivity.

- In Brazil, International Finance Corporation staff acknowledged the “impossibility” of achieving profitability by serving only the underbanked population. Instead, it supported some clients in serving a broad spectrum of the population, including underserved groups. Yet the oligopolistic structure of the banking sector drove up costs and left only less profitable market segments to smaller banks and financial institutions.

- In Mozambique, only mobile money appeared to offer a viable and sustainable business model for serving many rural and excluded low-income people.

- In Indonesia, major banks found that, even after moving to digital financial services banking (such as expanded ATM networks) to reduce costs, delivering financial services to the excluded groups remained economically unviable. The International Finance Corporation used its responsible microfinance advisory services project to support the Indonesia Microfinance Forum to expand and adopt responsible finance principles and to assist members with adhering to its charter through training and awareness raising. The project was successful, resulting in 3.25 million clients receiving responsible microfinance services.

- In Colombia, the high cost of services was the leading reason (cited by 65 percent of the unbanked population) for not having an account. Commercial banks failed to find a viable model of services for financial inclusion, although some credit cooperatives and microfinance institutions were able to operate sustainably. The World Bank Group approach emphasized strengthening the payment system, enabling digital infrastructure, and fostering competition in the financial and the information and communication technology sectors.

Sources: Global Findex 2021; Independent Evaluation Group country case studies.

The World Bank used DPOs to support credit services with mixed success (77 percent average success rate). Upstream policy, regulatory, and institutional reforms often led to the expansion of service delivery, but not always. A World Bank DPL supported the Colombian government in establishing a regulatory framework to underpin the Priority Interest Housing Program for Savers. The program provided subsidies to selected types of families to facilitate the purchase of a house. With a target of providing 10,000 low-income families with access to affordable housing, the program supported 35,000 low-income families in gaining such access, far exceeding its target. By contrast, in Moldova, a DPL supporting legal reform to facilitate the use of movable assets as collateral did not meet its target. It expanded the types of eligible movable capital, created an out-of-court settlement mechanism, and established a notification registry to ensure transparency. However, it did not reach the targeted increase in the share of loans secured by movable collateral, which decreased over the project life.

Payments were mostly successfully supported by World Bank DPOs and investments and by IFC AS. In Panama, a DPL supported the government’s effort to create a single registry of beneficiaries and a single payment platform for its social payment and education benefit programs. At evaluation, the project had far exceeded its targets. The percentage of extremely poor people benefiting from at least one social assistance program rose from 37 percent in 2014 to 81 percent in 2018. The use of a “social card” for payments through the National Bank of Panama increased from 0 percent in 2014 to 80 percent by 2019. In Rwanda, a DPL supported the government’s social protection and health policy reforms, initially in 30 pilot sectors. The operation included a policy to provide direct payments of wages to the individual bank accounts of low-income Rwandese without intermediaries. At evaluation, the target of 35 percent of eligible households was far surpassed, with 77 percent of such households reached.

IFC AS supported savings more frequently than did other instruments. In Mexico, an IFC investment supported a microfinance client to mobilize savings and insurance through an integrated business model. Savings deposits rose from $33 million in 2012 to $68 million, and the number of depositors grew from 299,489 in 2012 to 523,808 by the end of 2016. In Ethiopia, a World Bank investment loan supported the promotion of new pastoral savings and credit cooperatives. In total, 1,305 new savings and credit cooperatives became operational, exceeding a target of 1,110. In target communities, the share of households belonging to the savings and credit cooperatives reached 15.3 percent, exceeding the target of 10 percent.

Digital Financial Services

Although the emphasis on DFS grew over the evaluation period, the success rate of DFS operations varied. The average success rate for World Bank projects focusing only on DFS was 72 percent. IFC was equally successful with digital and traditional services and more successful with projects using both. In some cases, well-placed technical assistance projects appeared to bring major benefits. In Bangladesh, IFC helped bKash to develop operational procedures and a strategy for an e-wallet payment solution and to implement merchant acquisition and rollout. By the end of 2017, it had exceeded its target of 45,000 merchants, with 50,516 accepting retail payments or mobile banking transactions. In addition, at 30.9 million accounts linked to mobile banking systems, it far exceeded its target of 20 million. In Mozambique, IFC supported the entry of M-PESA (Vodafone) as a mobile money service provider, as it sought to expand its customer base and merchant network in Mozambique. Since 2016, the growth rate for mobile wallets was three times faster than that for traditional bank accounts. A network of merchants where cash could be deposited and withdrawn advanced the ability to reach rural citizens with payment services. M-PESA emerged as the leading mobile money provider, with 4.2 million customers in a country of 31 million people.

Considering the accelerated emphasis on digital services in response to COVID-19, in several countries, the Bank Group worked to integrate the digitalization of payments with the opening or use of digital payment accounts to receive them, with mixed results. To enable financial access, a digital payment account created to receive social G2P payments must allow other uses, such as other payments and deposits. In multiple case study countries, client country governments, often with World Bank support, used digitalized payments as vehicles to expand financial access. Examples include the following:

- Colombia: The government responded to the pandemic by bolstering electronic payments, including by expanding existing conditional cash transfer programs and introducing Ingreso Solidario, which provided nonconditional monetary support to households living in poor and vulnerable conditions through electronic or digital transfers to deposit accounts. Ingreso Solidario took advantage of Colombia’s newly enacted regulatory modernization that supported DFS to deliver cash transfers through deposits into bank accounts and mobile wallets. By July 2020, this program had benefited 2.7 million households, most previously unbanked. The World Bank advised and supported this program, including through a DPL that expanded and redesigned the primary database for social protection.

- Mozambique: The 2020 COVID-19 response DPO included in its results framework a target of making 150,000 social transfers through electronic payments, including 90,000 to women. This target was a fraction of the government’s overall objective to more than double social protection payment beneficiaries. The World Bank intended the electronic payments to provide beneficiaries who lacked a financial account with an account usable to receive and make payments. To reach citizens lacking adequate identification documents, the central bank issued “comfort letters” to mobile money operators, allowing them to open accounts for beneficiaries lacking official identification.

At the same time, many accounts that were quickly opened or employed for crisis response G2P payments may not produce sustainable, usable financial services to beneficiaries. First, as noted, in multiple countries, lack of money is the primary reason for not using financial services; thus, if payments are not sustained, account usage may not last. Although the World Bank encouraged a general switch to digital G2P social payments in Mozambique, both cyclone and COVID-19 payments had limited life spans. Informed observers indicated that Mozambique lacked the fiscal means to sustain social payments introduced as a COVID-19 response. Although the ultimate fate of such accounts is not yet known, some countries recognize the need to mitigate these risks. For example, by contrast, Bangladesh had already begun to take steps toward establishing a common G2P payment platform, including pilot digital payments using a few different payment modalities, such as the Bangladesh Post Office, mobile financial services, and agent banking. Through the pilot, it issued cards to over 28,000 beneficiaries of its cash transfer programs across 10 subdistricts, with positive outcomes in terms of time and cost savings to beneficiaries.

In other countries, G2P accounts did not enable beneficiaries to use them for payments or savings. In Pakistan, beneficiaries could use the G2P transfer accounts only to withdraw benefits.4 In the Philippines, the Social Amelioration Program opened digital accounts for beneficiaries allowing it to disburse payments to a huge number of additional enrollees. However, it did not train beneficiaries in financial literacy; therefore, millions of accounts were predicted to become dormant.

In other countries, G2P never became a focus for financial inclusion, even under COVID-19. In Tanzania, Bank Group support for financial inclusion continued its focus on other areas, including digital payments, but not G2P. In several countries, IFC or the World Bank focused on ramping up support for SMEs (outside the scope of this evaluation) during COVID-19.

Evidence on Outcomes

Evidence on economic and social outcomes for microenterprises, low-income households, and excluded groups is weak. The portfolio review examined 293 financial inclusion project evaluations and found that 91 percent had no information on whether the projects had improved household or microenterprise outcomes. Only a handful of projects collected information on whether beneficiary enterprises had expanded employment or increased sales. Very few tracked whether adult users accelerated economic activity, increased their incomes, improved their homes, or diversified their sources of income. Approximately the same 91 percent of projects provided no evidence of poverty outcomes for beneficiaries. World Bank investment financing had a somewhat better rate of providing information on beneficiaries than other instruments.

In the country case studies, experience in tracking outcomes varied widely, with most countries lacking granularity or focusing on headline access numbers. In Brazil and Indonesia, case studies observed some improvements in the monitoring and evaluation of outcomes over the evaluation period. In general, there was no basis for linking financial inclusion to any economic or social outcome. A few projects—like some in Indonesia and Pakistan—benefited from outcome or impact studies. Countries, such as Mozambique, relied primarily on internationally generated indicators, such as Global Findex, although one World Bank project planned an ambitious postimplementation evaluation.

Given the lack of information on outcomes, attribution of observed improvements in outcomes was also difficult. In countries where multiple donors are active or there is independent government or private sector activity in financial inclusion, it was often challenging to attribute observed gains in financial access and inclusion to the Bank Group’s support. In a country such as Mozambique, with relatively few donors supporting financial inclusion, it is easier to attribute reforms to specific sources, but information on outcomes is scarce. In Indonesia, where some outcome indicators were disappointing, it was hard to tell what the Bank Group’s share of responsibility was because of the engagement of multiple actors. In Bangladesh, it was possible to attribute outcomes to activities on which the World Bank took the lead. However, where the Bank Group was one partner among several, it was difficult to disaggregate the Bank Group’s contribution.

- In this chapter, we assess success at the project and objective levels using portfolio analysis of the Independent Evaluation Group validated or evaluated projects within scope. For the analysis, we considered indicators with an “above the line” rating (that is, those rated satisfactory or moderately satisfactory) to be successful and assigned them a value of 1. We considered those “below the line” (that is, those rated not achieved or mostly not achieved) to be unsuccessful and assigned them a value of 0. Then we calculated the average success rate per project and objective. The calculation encompassed all output and outcome indicators with available ratings within each project but excluded objectives found in fewer than four projects. A project may have multiple objectives. In particular, we coded 293 evaluated projects for effectiveness, and they had 322 financial inclusion objectives. Because there is no validated evaluation system for World Bank advisory services and analytics, there are no accepted data on its effectiveness. Consequently, advisory services and analytics are not treated in this chapter.

- Access is the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency’s only identified objective in the financial inclusion domain, but only one operation with an access objective has been evaluated. It was successful.

- In general, it is difficult to compare the success rates of International Finance Corporation investments, which bear private commercial risks, with other types of World Bank Group projects. It should be noted that a 69 percent success rate is well above the institutional average for all investments, which in 2021 had a three-year rolling average rating of 58 percent.

- For the portfolio review, we included only government-to-person projects when they had a clear financial inclusion objective.