Financial Inclusion

Chapter 1 | Introduction and Approach

Highlights

This evaluation explores how and with what effect the World Bank Group has supported financial inclusion for microenterprises, poor households, women, and other excluded groups.

Financial inclusion refers to expanding access to and use of financial services, including among low-income households, microenterprises, women, and other traditionally excluded groups. The inclusion concept goes beyond access, which refers to owning a financial account. Financial inclusion has been understood to have the potential to help reduce poverty and achieve global development goals, although empirical evidence in the literature on its benefits in lifting people out of poverty has substantial gaps.

Financial inclusion has advanced substantially internationally over the evaluation period, although disadvantaged groups remained disproportionately excluded. Digital technologies have been vital in expanding access to and use of financial services. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many adults made their first digital payments.

Consistent with its understanding of financial inclusion as a key tool to achieve its twin goals, the Bank Group gave it prominence. To strengthen impact, the Bank Group initially focused its Universal Financial Access 2020 strategy on 25 countries where over 70 percent of financially excluded people resided.

This evaluation aims to enhance learning from the Bank Group’s experience in supporting client country efforts to advance financial inclusion.

Key subthemes include the Universal Financial Access 2020 initiative, women’s access to finance (gender), digital financial services, and the effects of and response to COVID-19.

This evaluation links financial inclusion challenges to Bank Group responses and (where observable) outcomes. Subject to several limitations, it uses mixed methods to explore whether the Bank Group is doing the right things and doing them right.

The Importance of Financial Inclusion

Financial inclusion refers to expanding access to and use of financial services by the microenterprises, poor households, women, and other excluded groups (MPWEG). It means increasing access to and use of financial services in beneficial ways by those formerly lacking access or not using such services (box 1.1).1 Financial inclusion interventions target MPWEG, including the poorest people around the world (Prahalad 2004). The financial inclusion portfolio identified by the Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) includes MPWEG beneficiaries. The evaluation excludes projects exclusively supporting small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and those aimed at underserved populations in high-income countries.

Box 1.1. Financial Inclusion Compared with Access

Access to an account may not mean use of an account. The 2017 Global Findex found that 20 percent of all people who had an account in 2017 did not use it. Financial inclusion is a more expansive concept than access. It explicitly envisions both access to and use of a range of financial products and services, consisting of credit, savings, payments, and insurance, including through digital finance. Furthermore, the World Bank Group has stated that inclusive services should be useful, affordable, sustainable, and responsibly delivered.

Sources: Demirgüç-Kunt, Klapper, and Singer 2017; World Bank 2015b.

Improving financial inclusion might help reach several development goals and the World Bank Group’s twin goals—reducing extreme poverty and boosting shared prosperity. Financial inclusion has been linked to at least 9 of the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals: no poverty; zero hunger; good health and well-being; gender equality and women’s empowerment; decent work; economic growth and full and productive employment; industry, innovation, and infrastructure; reduced inequalities; and partnerships for the goals. Consistent with this, the Bank Group views financial inclusion in low-income countries as a key enabler to achieve its twin goals (World Bank 2022a).

Transforming irregular income flows into a dependable resource to meet daily needs is a key challenge for poor people. Collins et al. (2009) found that managing day-to-day cash flow was one of the three main drivers of the financial activities of poor people. The income of the people at the bottom of the economic pyramid is not only low but also volatile because they rely on a range of unpredictable jobs or on weather-dependent agriculture. Another challenge they face lies in meeting costs if a major expense (such as a home repair or medical service) arises or if a breadwinner falls ill. For example, Global Findex 2021 finds that only 55 percent of adults in developing economies could access extra funds within 30 days without much difficulty, and this percentage is lower for women (50 percent) and poor people (40 percent). In upper-middle-income countries, 72 percent of adults could access such emergency funds. By contrast, in low-income countries and lower-middle-income countries, only a minority (42 percent and 41 percent, respectively) could do so. Having access to a financial account and benefiting from its services—savings, credit, and insurance, among others—is expected to give poor people a chance to save their money safely, increase financing for their microbusinesses, improve investments in education and health, and reduce their vulnerability to shocks.

However, empirical evidence on whether financial inclusion can help achieve the Sustainable Development Goals and the Bank Group’s twin goals has substantial gaps. Although financial inclusion is linked by the Bank Group and others with poverty alleviation and resilience, the academic literature suggests that the evidence on this is mixed and incomplete. For example, there is abundant, mixed evidence on credit services but far thinner, mostly positive evidence on savings. Although financial inclusion is generally positively correlated with economywide growth and employment, evidence does not tightly link it to the well-being of poor people measured in terms of their income, consumption, or exit from poverty. It is also unclear whether investments in financial inclusion will yield greater gains than alternative approaches to poverty alleviation (box 1.2). At the same time, systematic reviews of evidence suggest critical gaps and limitations in evidence, particularly concerning the effects of government-to-person (G2P) payments, mobile banking, insurance, and the income benefits of all financial services.2 These gaps make it hard to directly link access and usage of financial services to beneficial impacts for MPWEG, such as improved income, education, health, or social status. This may be in part because the channels through which financial inclusion yields benefits are indirect and long term.

Box 1.2. Financial Inclusion and Poverty: Mixed Evidence and Important Gaps

The academic literature on the link of financial inclusion to poverty outcomes offers some positive and some mixed evidence but has significant gaps. An important protocol-based systematic review of reviews of rigorous evidence found the impacts of financial inclusion on poverty to be “small and variable.”a It found that “although some services have some positive effects for some people, overall financial inclusion may be no better than comparable alternatives, such as graduation or livelihoods interventions” (Duvendack and Mader 2019).b The review also found inconsistent effects of financial inclusion on core poverty indicators, such as incomes, assets, or spending, and a “small or nonexistent” benefit for health and social outcomes. Finally, financial inclusion was found unlikely to be transformative in terms of lifting people out of poverty. However, the review did find a small positive effect of savings on the well-being of poor people and sometimes positive impact of financial inclusion on women’s empowerment, depending on program design, context, and how empowerment is defined (Duvendack and Mader 2019).c

Although Duvendack and Mader considered literature up to 2017, subsequent literature surveyed in the Independent Evaluation Group’s structured literature review found more mixed evidence, including both positive and negative effects of savings mechanisms on poverty, positive evidence on the benefits of financial literacy interventions, mixed evidence on benefits to farmers, and evidence of negative benefits of microcredit (including overindebtedness).

Several authors have responded to the gaps in evidence with insights into why it may be difficult to prove the benefits of financial inclusion. Ogden (2019) argues that “what we can learn from [systematic reviews] can often be less than what we can learn from a theory-informed, nonsystematic but thorough reading of the research.” Storchi, Hernandez, and McGuinness (2020) argue that the lack of an apparent direct impact of financial inclusion on poverty is because the channels through which financial inclusion enhances welfare are indirect, such as helping poor people build resilience and seize opportunities, often through long-term investments, such as education, that lack an immediate payoff. Investments to improve skills or physical well-being (health and mobility) may have downstream benefits that are hard to observe.

Sources: Duvendack and Mader 2019; Independent Evaluation Group literature review (appendix D); Moore et al. 2019; Ogden 2019; Storchi, Hernandez, and McGuinness 2020.a. Duvendack and Mader (2019) reviewed 11 studies from 2010 onward that synthesized the findings of other studies (meta-studies) regarding the impacts of a range of financial inclusion interventions worldwide on economic, social, gender, and behavioral outcomes.b. Livelihood interventions seek to stimulate employment and income growth for poor people by promoting growth and employment in relevant sectors, strengthening delivery of social services, and empowering the community. Graduation interventions provide a simultaneous set of support to poor households that includes an asset to spur income generation, training and coaching on the use of the asset, food or cash support, health education, and financial services.c. The review also found that evidence of empowerment was “circumstantial” and that methods and measures of empowerment were inconsistent.

Global Progress on Financial Inclusion

Globally, financial account ownership (“access”) has advanced substantially since 2011 but is far from universal. The share of adults who own a bank account rose globally from 51 percent in 2011 to 76 percent in 2021. The account ownership rate doubled in low-income countries and increased by over 40 percent in lower-middle-income countries. Despite this, in 2021, 23.8 percent of the world adult (15 years of age and older) population (about 1.4 billion people) remained “unbanked”—that is, lacking an account at a financial institution or through a mobile money financial service provider.3 For some groups, this rate was higher: 26 percent of women, 28 percent of the bottom 40 percent in terms of income, and 34.5 percent of youth.4

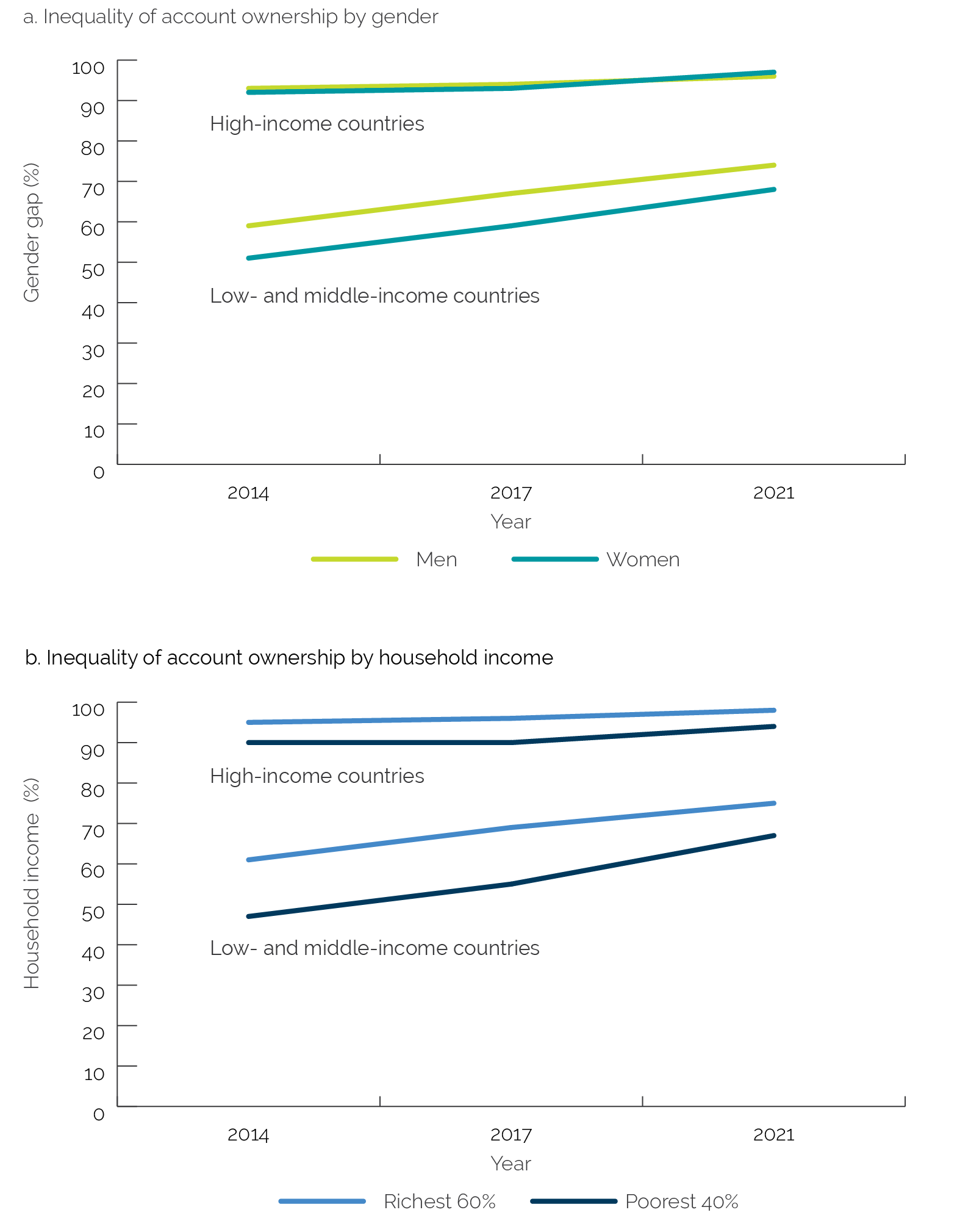

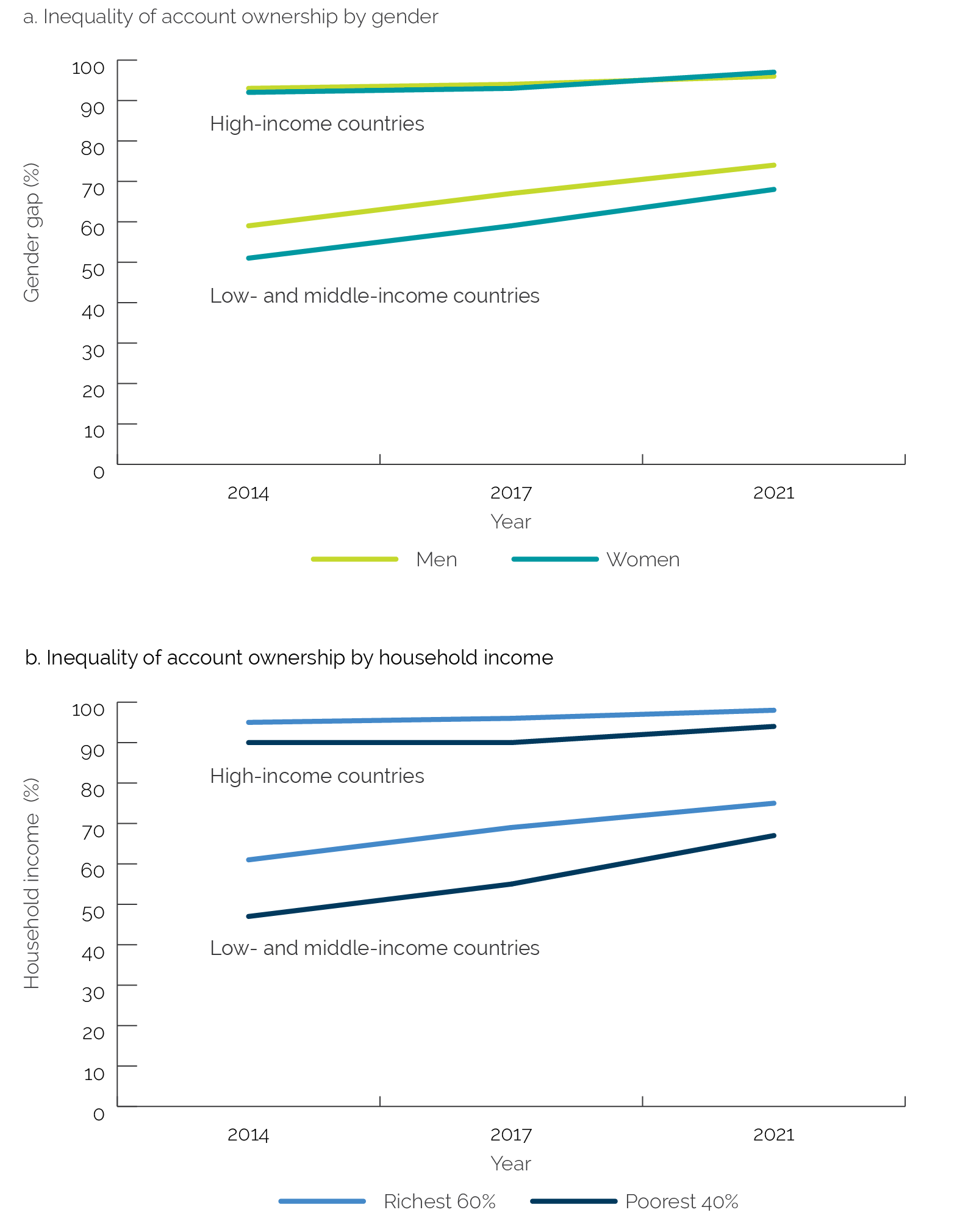

Women’s and low-income households’ access to financial services improved over time. The gender gap in account ownership in lower- and middle-income countries decreased from approximately 8 percentage points in 2017 to 6 percentage points in 2021 (figure 1.1, panel a). The gap persisted in part because of legal and cultural norms,5 whether directly through restrictions on women’s contracting and ownership rights or indirectly through their differential mobility, access to technology, documentation, literacy, numeracy, and economic roles in families (World Bank 2018c). The gap between richer and poorer households also narrowed in lower-middle-income countries from 14 percent in 2011 to 8 percent in 2021 (figure 1.1, panel b). Rural access has increased strongly, but in Africa, a rural access gap remains (Bull 2018).

Figure 1.1. Account Ownership over Time by Gender and Household Income

Figure 1.1. Account Ownership over Time by Gender and Household Income

Source: Global Findex 2021.

Account ownership does not always result in financial inclusion. Thirteen percent of accounts held by adults in 2021 had not been used in the prior year (Demirgüç-Kunt et al. 2022). In lower-middle-income countries, this rate was 24 percent. Where financial access is supply driven, demand for the services supplied may lag. India, which rolled out 300 million accounts in a few years under its Jan Dhan Yojana plan, had a 48 percent dormancy rate by 2017 (Bull 2018), although this subsequently declined in part because of substantial financial incentives from the government.

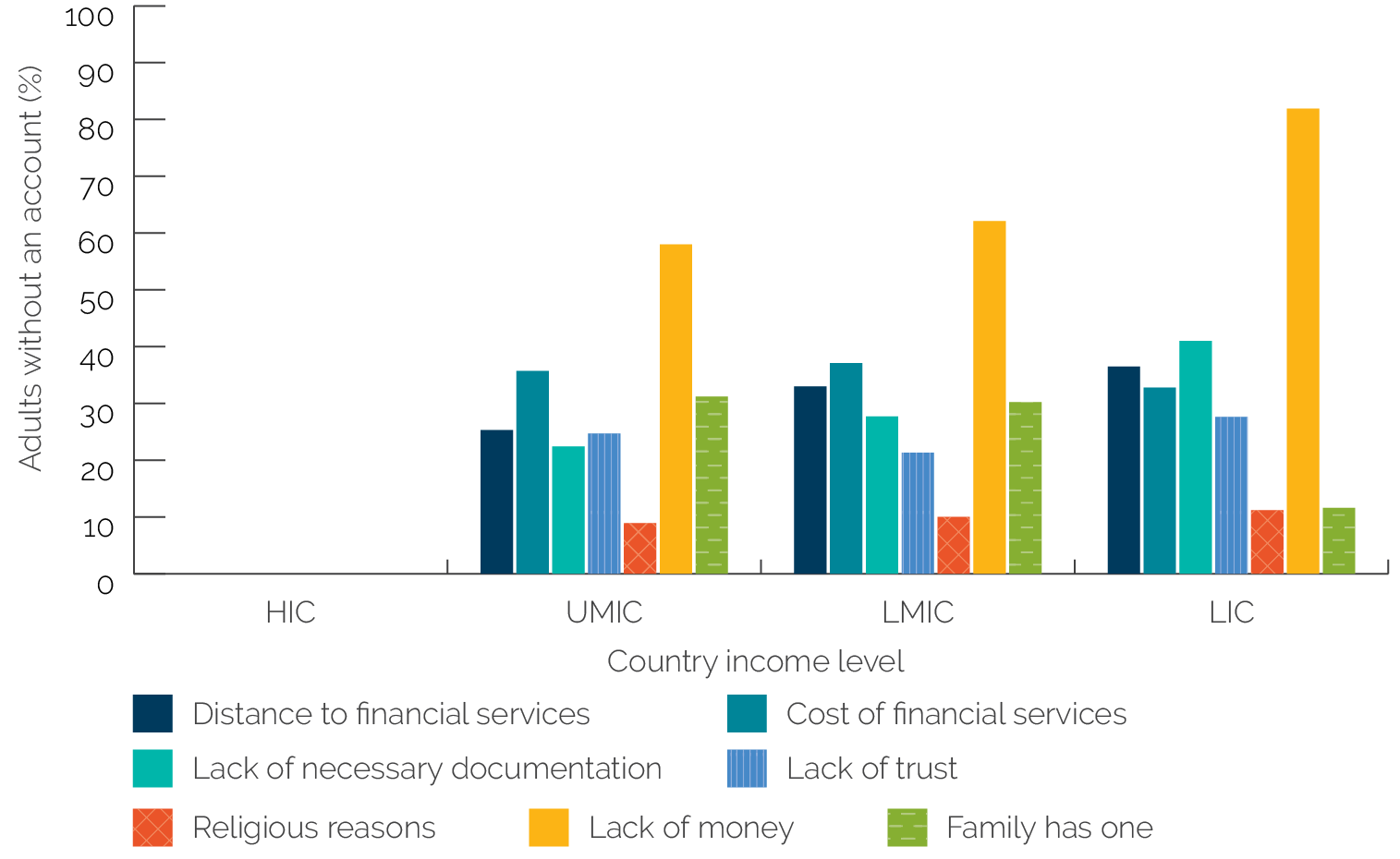

In every Region and country income classification, the leading reason for not using financial services is a lack of money. The second most common reason adults lack accounts is that they have access to financial services through other family members. Nonetheless, more than 20 percent of the excluded groups report that the cost of services, distance to services, and documentation requirements explain their lack of an account (figure 1.2).

Digital financial services (DFS) played a central role in expanding access to and use of financial services.6 DFS includes digital payments of all kinds and other digitally delivered financial services globally; 64 percent of adults sent or received digital payments in 2021 compared with 44 percent in 2014. In low-income countries, this rate increased from 12 percent in 2014 to 35 percent in 2021. Mobile money is credited with the lion’s share of improved access in Africa, where 33 percent of adults had a mobile account in 2021. It has also been growing rapidly in Latin America and the Caribbean, where 23 percent of adults have a mobile account. However, the global growth of DFS has been uneven across countries because digital payment systems and other digitally delivered financial services depend heavily on physical and financial infrastructure and the existence and enforcement of relevant laws and regulations (appendix E).

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the demand and drive for DFS. Many governments strengthened their regulatory or infrastructural capacity for DFS. Further enabling steps included associating social payments related to COVID-19 with new or existing financial accounts, enhancing citizens’ digital identification to meet eligibility requirements for financial services, and addressing regulatory and legal barriers to access and use. The percentage of adults in developing countries who had received digital payments rose from 44 percent in 2017 to 57 percent in 2021 (Demirgüç-Kunt et al. 2022).7 Global Findex estimates that in India, about 80 million adults made their first digital merchant payment during the pandemic, and in China, over 100 million adults (11 percent) did so. However, the temporary nature of government transfers related to COVID-19 and the limited functionality of some accounts raised questions about the degree and sustainability of inclusion achieved.

Figure 1.2. Reasons for Adults Not Having an Account

Source: Global Findex 2021.

Note: The graph shows the percentage of adults with no account citing a given barrier as a reason for having no financial institution account. HIC = high-income country; LIC = low-income country; LMIC = lower-middle-income country; UMIC = upper-middle-income country.

Evolution of World Bank Group Engagement in Financial Inclusion

The Bank Group has promoted financial inclusion over the evaluation period, starting with the Universal Financial Access 2020 (UFA2020) initiative. The UFA2020 initiative, announced by the Bank Group president in 2013 and fully launched in 2015, aimed to accelerate progress on financial inclusion to lift people out of poverty. Its ambitious goal of universal access was in its name “ensuring that people worldwide can have access to a transaction account” (World Bank 2022a) or an electronic instrument to store money, send payments, and receive deposits. This meant enabling about 2 billion adults who were financially excluded in 2014 to gain access to a transaction account by 2020. In support of this aim, the World Bank and the International Finance Corporation (IFC) anticipated support work such that 1 billion unbanked people would gain access to a transaction account (400 million World Bank; 600 million IFC) through targeted interventions by 2020.8 They also envisioned that they would “convene and energize a coalition of partners” to ensure that the universal access goal was realized. Although the focus on large numbers of new accounts drew some criticism, management saw financial access as a step toward full inclusion. In support of UFA2020, the World Bank sponsored the Payment Aspects of Financial Inclusion initiative (box 1.3). The World Bank also intended to integrate financial inclusion into the Financial Sector Assessment Programs (FSAPs) that are conducted jointly with the International Monetary Fund.

Box 1.3. Payment Aspects of Financial Inclusion

In 2014, the World Bank Group and the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures at the Bank for International Settlements convened a task force of experts on Payment Aspects of Financial Inclusion to recommend how payment systems and services could enhance financial inclusion efforts. Given the focus of the Universal Financial Access 2020 initiative on transaction accounts, the 2016 Payment Aspects of Financial Inclusion report became an organizing framework with guidance to do the following:

- Support expanded access to transaction accounts and use of electronic payment services.

- Publicize the importance of safe and efficient payment services for the well-being of individuals, households, and businesses and as a gateway to a broader range of services.

- Advance market efficiency, flexibility, integrity, and competitiveness.

- Facilitate the establishment of a balanced and proportional regulatory environment for effective, reliable, safe, and cost-efficient access to payment services.

Sources: Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures and World Bank Group 2016; World Bank Group interviews.

The Bank Group implemented the UFA2020 initiatives through lead units and in collaboration with partners. The World Bank’s Finance, Competitiveness, and Innovation Global Practice and IFC’s Financial Institutions Group led the implementation of the UFA2020 initiative on behalf of the Bank Group. They worked in collaboration with the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP; box 1.4) and the World Bank’s Development Research Group, as well as other Global Practices.9 The Bank Group lead units engaged with external partners (such as the Financial Inclusion Support Framework and Harnessing Innovation for Financial Inclusion; box 1.4), bringing in private foundations (such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Mastercard Foundation, and the Visa Foundation), global organizations (the United Nations and the Group of Twenty), and bilateral donors, among others.

Box 1.4. Leveraging Partnerships to Support Financial Inclusion

The Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP), hosted by the World Bank Group, is a multidonor partnership of leading development agencies that uses action-oriented research to “test, learn, and share knowledge” on financial inclusion. It aims to help build inclusive and responsible financial systems that enable poor people to capture economic opportunities, access essential services, and build resilience. CGAP intends to inform and enable development partners to implement solutions and bring them to scale. The former Finance and Markets Global Practice called CGAP its “innovation lab” and “knowledge hub.”

The Financial Inclusion Support Framework, launched in 2014, is a multidonor trust fund financing a global technical assistance program that aims to enhance country-led reforms and other actions to achieve national financial inclusion goals, often by supporting Bank Group technical assistance. It launched country support programs in 8 out of the 25 Universal Financial Access 2020 priority countries.

The Harnessing Innovation for Financial Inclusion program supports use of technology and innovation to sustainably increase financial inclusion. Hosted by the Bank Group and CGAP with United Kingdom government funding, it finances knowledge, technical assistance, and awareness raising on digital financial services.

Sources: Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (https://www.cgap.org); Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office 2022; Independent Evaluation Group interviews; World Bank 2022b.

The Bank Group’s strategy on financial inclusion centrally featured country engagements. The Bank Group at first centered its UFA2020 strategy on 25 countries where 70 percent of the world’s unbanked population lived but ultimately engaged on universal financial access with over 100 countries (World Bank 2018b). The World Bank described its support of countries as an “integrated and unified approach” focusing on intertwined areas to achieve financial inclusion. It would use national financial inclusion strategies (NFISs) as a basis to support modernization and reform of payment systems, diversification of financial services, leveraging of financial technology (fintech) for inclusion, strengthening of consumer protection and capabilities, data generation, and more.

With UFA2020, IFC defined an approach to advance financial access through its financial institution partners. IFC developed Country Action Plans for multiple UFA2020 priority countries and worked to increase financial access through partnerships with financial service providers, emphasizing underserved markets. IFC aimed to efficiently reach large numbers of the excluded groups by focusing on larger markets with big gaps in account access and partnering with existing institutions that enabled significant outreach. Under IFC’s leadership, a variety of international firms and organizations made commitments on the number of new accounts they would create or underserved customers they would serve (World Bank 2015d, n.d.). For example, Mastercard and Visa each committed to reaching 500 million excluded or underserved people. By December 2015, the partners had agreed on principles to avoid double counting and to focus on first-time access.

IFC separately highlights financial inclusion in its IFC 3.0 strategy. IFC 3.0 identifies opportunities in access to finance, including strengthening domestic banking sectors, increasing lending to nonbank financial institutions (NBFIs) to support SMEs, and supporting digital finance as a cost-effective route to financial inclusion for unbanked and underserved consumers (IFC 2018). It also supports the deepening of local capital markets to mobilize funds, risk management and responsible finance practices for microfinance institutions (MFIs), and institutional strengthening. IFC’s microfinance deep dive emphasizes scaling up by building sustainable financial service providers for underserved groups, especially in countries in fragile and conflict-affected situations and International Development Association countries, and supporting digital finance. The fintech deep dive highlights how IFC’s support can advance the financial inclusion of micro and very small enterprises and other underserved clients. As part of the COVID-19 response, IFC created the base of the pyramid platform and the working capital solutions facility to help mitigate the impacts of the pandemic on economic growth and livelihoods through long-term financing and working capital to banks focused on micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), MFIs, and NBFIs.

The Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) has recently highlighted the importance of financial inclusion for women. MIGA has not traditionally defined overarching financial inclusion goals (as defined in this evaluation). Its most recent strategy sets a new course in this respect, with statements embracing “inclusion” in general and its fiscal year (FY)21 Gender Strategy Implementation Plan explicitly emphasizing the importance of women’s access to digital services.

Although the Bank Group has not formally adopted a new financial inclusion strategy since UFA2020, it has shifted its emphasis over time toward DFS. In 2018, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund announced the Bali Fintech Agenda, with 12 policy elements aimed at helping countries to broadly enable fintech, ensure financial sector resilience, address risks, and promote international cooperation (World Bank 2018a). The Bank Group and the International Monetary Fund framed the agenda in terms of enhancing access to financial services (IMF 2018). Portfolio emphasis on DFS took off before COVID-19 and accelerated with the COVID-19 response. The World Bank aimed to improve conditions enabling access to and use of DFS. Recognizing the critical role that lack of formal identification played in exclusion from health, educational, social, and financial services and economic opportunities, the World Bank launched its Identification for Development (ID4D) program in 2016 with multiple partner donors. It aimed for the universalization of digital identification. The G2Px program was a “sister” activity launched in early 2020, aimed at advancing digitalization of G2P payments. It intended to advance financial inclusion, women’s economic empowerment, and government fiscal savings. Neither ID4D nor G2Px focused primarily on financial inclusion, but both supported relevant activities.

The Bank Group’s focus on gender in financial inclusion projects has also increased over time, accelerating from FY18 onward. IEG’s 2021 assessment World Bank Group Gender Strategy Mid-Term Review (World Bank 2021b) notes a strengthening of gender focus in financial inclusion after the rollout of the 2016 strategy. Under the 18th Replenishment of the International Development Association (for 2017–20), the World Bank committed to take action on gender gaps in access to and use of financial services and to provide sex-disaggregated reporting and targeting (IDA 2016). The Bank Group also committed in its 2018 proposal for a capital increase to work in International Bank for Reconstruction and Development countries to close gender gaps and expand the use of financial services.

The Bank Group’s involvement in financial inclusion for MPWEG has been substantial. During the evaluation period, the Bank Group financed nearly 1,700 financial inclusion activities worth nearly $30 billion and engaged in important knowledge development and global partnerships. We assessed the Bank Group’s work on financial inclusion for MPWEG and other financially excluded or underserved groups from 2014 to 2021. The World Bank’s financial inclusion portfolio consisted of 429 World Bank lending projects worth almost $23 billion, including over $11 billion in investment financing and an estimated $12 billion in development policy financing, and 677 advisory services and analytics (ASA). The evaluated IFC financial inclusion portfolio included 189 investments worth $5 billion and 360 advisory services (AS). The portfolio also included six MIGA guarantees totaling $1 billion (table 1.1) but only one evaluated project, limiting the inferences that may be derived from its experience. Beyond this portfolio, the Bank Group played a central role in leading the UFA2020 drive for universal financial access, in mobilizing partnerships in support of financial inclusion, and in generating financial inclusion knowledge and public goods.

A key Bank Group resource drawing global attention to financial inclusion has been the Global Findex database (and report), introduced in 2011. The triannual indicators emerged as a gold standard for benchmarking and evaluating progress on financial inclusion for most of the world. Over time, the Global Findex database has included additional indicators to enhance knowledge about access to and use of formal and informal financial services and digital payments and to offer insights into behaviors enabling (or limiting) financial resilience. The 2021 Global Findex covers 123 economies.

Table 1.1. Estimated Parameters of the World Bank Group’s Financial Inclusion Portfolio in the Evaluation Period (from 2014 to mid-2022)

|

Institution |

Evaluated Projects |

Projects |

Estimated Volumea, b |

|||

|

(no.) |

(%) |

(no.) |

(%) |

(US$, millions) |

(%) |

|

|

IFC |

162 |

77 |

549 |

37 |

5,477 |

30 |

|

IFC AS |

101 |

48 |

360 |

24 |

330 |

2 |

|

IFC IS |

61 |

29 |

189 |

13 |

5,147 |

28 |

|

MIGA |

1 |

0.0 |

6 |

0.4 |

1,078 |

6 |

|

World Bank (without DPO) |

49 |

23 |

924 |

63 |

11,647 |

64 |

|

World Bank ASAc, d |

0 |

0.0 |

677 |

46 |

337 |

2 |

|

World Bank IPF |

47 |

22 |

236 |

16 |

11,115 |

61 |

|

World Bank P4R |

2 |

1 |

11 |

1 |

195 |

1 |

|

Total, World Bank Group (without DPO) |

212 |

100 |

1,479 |

100 |

18,200 |

100 |

|

World Bank DPO |

87 |

100 |

182 |

100 |

11,591 |

100 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio review and analysis.

Note: The evaluation period covers fiscal years from 2014 to mid-2022. Fiscal year 2022 considers projects approved by December 31, 2021 (or effective by December 31, 2021, for MIGA projects). AS = advisory services; ASA = advisory services and analytics; DPO = development policy operation; IFC = International Finance Corporation; IPF = investment project financing; IS = investment services; MIGA = Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency; P4R = Program-for-Results.a. To estimate total volume related to financial inclusion in DPOs and other multicomponent projects, the projects’ committed amount was allocated proportionally among components (for example, prior actions for DPOs). Only components related to financial inclusion were considered. Where a component had multiple subcomponents, the committed amount was allocated proportionally to those subcomponents addressing financial inclusion.b. Volume for unevaluated projects was estimated based on the stratified random sample design, reflecting a 95 percent confidence level. The sampling framework considered institution, instrument, Region, and country income level as strata.c. For advisory projects, expenditure values are used. These values are not directly comparable to volumes associated with financing projects.d. The Independent Evaluation Group used a keyword search to identify 1,205 World Bank ASA projects potentially related to financial inclusion. A random sample reflecting a 95 percent confidence level produced a 43.8 percent rate of false positives. This figure was applied in projecting from the sample to the population.

Evaluation Objective, Scope, and Methodologies

The main objective of this evaluation is to enhance the Bank Group’s learning in supporting client countries to advance financial inclusion, including access to and use of financial services. Its learning centers on Bank Group support to financial inclusion, including its drive for universal financial access (the UFA2020 initiative), its support of NFISs, its promotion of women’s access to financial services (gender), its role in the growth of DFS, and its response to the effects of COVID-19.

This evaluation focuses on Bank Group support for financial inclusion—access to and use of financial accounts—for MPWEG. We examine the Bank Group’s work on financial inclusion—including both access to and use of financial accounts—in the period between FY14 and mid-FY22. It covers Bank Group interventions that target MPWEG as described in The Importance of Financial Inclusion section in chapter 1 (microenterprises, low-income households, and excluded groups, such as women, rural households and workers, and youth). Although the Bank Group includes SME finance under the rubric of financial inclusion, we have not included it within the scope of this evaluation. We have treated support to SMEs separately in earlier evaluative work (World Bank 2014, 2019). However, the portfolio includes projects that jointly benefit MSMEs.

We grouped our evaluation questions under relevance (“doing the right things”) and effectiveness (“doing things right”) as follows:

- Relevance

- To what extent have Bank Group country strategies aligned with the UFA2020 or country NFIS goals? How aligned is Bank Group engagement (global public goods, country programs, product mix, staffing, and partnerships) in financial inclusion reforms with country and financial sector priorities and conditions, including local needs and capabilities? What role did DFS play before and after the COVID-19 pandemic?

- Effectiveness

- How effective have the Bank Group’s financial inclusion interventions and programs (including the integrated approach focusing on nine intertwined areas) been in helping client countries strengthen their national policy and regulatory environment for financial inclusion and meeting the goals laid out in UFA2020?

- How effective have Bank Group efforts been in improving the supply and use of financial services? What role did DFS play?

- To what extent have Bank Group interventions contributed to improved economic and social outcomes for microenterprises and poor households, including those headed by women? Were the benefits sustained over time? To what extent did improved financial services foster resilience and adaptation of individuals and microenterprises during the pandemic?

- What country- and project-level factors explain success or failure? What lessons can be drawn from Bank Group experience?

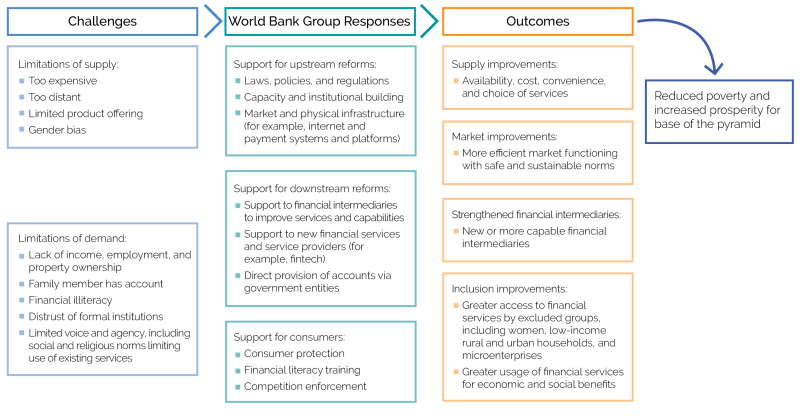

A logical framework guided our approach to this evaluation. This framework, introduced in the Approach Paper (World Bank 2021a), describes a logical connection between financial inclusion challenges, Bank Group responses, and intended outcomes (figure 1.3). Within this framework, limitations of supply and demand for financial services are addressed through a set of Bank Group responses. These responses include upstream reforms consisting of support for improved laws, policies, regulations, capacity building, and market and physical infrastructure. They also include downstream reforms containing support to financial intermediaries and other service providers and support to government programs that directly provide excluded citizens with accounts. In addition, responses may support consumers through consumer protection, financial literacy, and competition enforcement. The intended outcomes include improvements in the availability, cost, and quality of financial services; the capacity of financial intermediaries; the function of markets; and outcomes regarding access to and usage of financial services by underserved and excluded groups. The Bank Group is not the only source of responses, nor is it solely responsible for outcomes. Therefore, context and the activities of other actors must be understood to capture the relationships between challenges, responses, and outcomes.

Figure 1.3. Relationship between Challenges, World Bank Group Responses, and Outcomes

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The figure depicts World Bank Group activities (second column) responding to challenges in the domain of financial inclusion (first column). Bank Group interventions are intended to produce beneficial outcomes, denoted in the third column. Fintech = financial technology.

We used a mixed methods approach in this evaluation. The methodologies applied (detailed in appendix A) include the following:

- Portfolio review and analysis applied a systematic review of financial inclusion projects meeting defined selection criteria to identify design features and characteristics, achievement of objectives, and drivers of success. We identified and manually reviewed all 299 Bank Group evaluated projects for relevance and effectiveness, a stratified random sample of 197 unevaluated projects for relevance, and a stratified random sample of 105 unevaluated World Bank ASA projects similarly identified for relevance.

From this, we derived descriptive statistics and performed various statistical analyses of the resulting data, as follows:

- Field-based and desk-based case studies in 10 countries with embedded consideration of country strategy and diagnostic analysis. The 10 countries selected to represent the experience of the 25 UFA2020 priority countries were Bangladesh, Brazil, Colombia, the Arab Republic of Egypt, Indonesia, Mozambique, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Tanzania. All were subject to a desk study with document review and limited interviews, and six (Bangladesh, Colombia, Egypt, Mozambique, Nigeria, and the Philippines) further included in-person field missions. The studies followed parallel data collection methods and protocols to ensure harmonized treatment. A workshop of case study authors elicited hypotheses and supporting evidence deriving from them.

- Deep dives on DFS and gender. Deep dives provide a basis for enhancing the understanding of specific topics. Each included a brief literature review and drew from analysis of the portfolio and case studies, as well as select interviews and supplemental research, to provide a focused analysis.

- Structured literature review. The review examined evidence on the outcomes and impacts of financial inclusion. It supplemented prior academic structured reviews of the literature by reviewing literature since 2017 through a search of several leading databases of peer-reviewed journals, selecting for articles using robust methods.

- Global Findex 2021 analysis. We analyzed Global Findex 2021 data to better understand the state of financial inclusion in countries and the world and factors driving or constraining enhanced access to and usage of financial services.

- Semistructured interviews with Bank Group staff and management working in financial inclusion. We used a template of standard questions as a basis for dozens of interviews with relevant staff in addition to those conducted for case studies.

Limitations

We caution readers about the limitations of the evaluation, which were mitigated through the use and triangulation of appropriate methods and sources. Limitations include the following:

- Definition of financial inclusion. We focused this evaluation on services to MPWEG. Although the Bank Group often refers to SME-related activities when discussing financial inclusion, most of these activities (except when microenterprises and SMEs are jointly served by a project) are not treated in this evaluation. This means that initiatives such as the Women Entrepreneurs Finance Initiative, which addresses constraints on women-led SMEs, were out of scope.

- Sampling of important elements of the portfolio. Because of the large size of the portfolio and resource constraints, we constructed stratified random samples of the unevaluated Bank Group portfolio and of the large body of World Bank ASA projects. Although these samples were constructed to achieve a 90 or 95 percent level of confidence in generalizing to the population, as noted in relevant figures, they limit the types and levels of disaggregated analysis that can be conducted.

- Disruptions due to COVID-19 and natural disasters. This evaluation covers the period from FY14 to mid-FY22. It was originally launched in 2020 but was postponed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic interrupted fieldwork and delayed the availability of data from Global Findex 2020 (which became Global Findex 2021). Mission travel was constrained in some cases, and the delay imposed time and resource constraints on the evaluation. In Pakistan, massive flooding prevented us from carrying out fieldwork beyond a few interviews of Bank Group staff; thus, Bangladesh was substituted as a field-based study in South Asia.

- Lack of beneficiary-level data on outcomes and impacts. We found a dearth of data on Bank Group project outcomes and impacts, in terms of the usage of services provided and benefits realized by users. This challenge was more acute during COVID-19, when many rapidly implemented responses (including those in the domain of financial inclusion) collected only the most rudimentary output data. Most outcome data were not at the project level. We did not find ways to generate such data under the constraints we faced in our field activities.

- Difficulties of attribution. In many countries, the Bank Group operated in a context of multiple donor and government activities. Simultaneous or sequential efforts by governments and multiple donors and nongovernmental organizations clouded attribution of results. To the extent possible, we applied a contribution analytic framework to the case studies in judging how Bank Group activities “moved the needle.”

- Difficulties of judging the impacts of public goods and global engagements. The Bank Group has been a major producer of global public goods and contributor to global standards and knowledge. Initiatives such as the Global Findex and the Bali Fintech Agenda have broad influence, which is nonetheless very difficult to measure.

- Lack of MIGA data and strategic objectives for financial inclusion. Although we actively searched for MIGA engagement in financial inclusion, the portfolio review yielded only one evaluated MIGA project and six projects overall that fit the scope of this evaluation. The lack of evaluative data and examples, combined with MIGA’s own lack of strategic objectives in financial inclusion during the evaluation period, limits the ability to draw inferences specifically about MIGA guarantees. Multiple interviews with MIGA staff suggested that financial inclusion did not figure among its priorities. Therefore, although MIGA was never excluded from portfolio analysis and case studies, it rarely played a role, and no recommendations are offered for MIGA.

The report is organized into five chapters. The chapters that follow examine the relevance of Bank Group engagement in FY14 to mid-FY22 (chapter 2); the effectiveness of Bank Group engagement in FY14 to mid-FY22 (chapter 3); and country- and project-level factors explaining success and failure (chapter 4). Chapter 5 synthesizes our key findings and offers recommendations for enhanced Bank Group support for financial inclusion.

- The World Bank Group defines financial inclusion as the use of financial services by individuals and firms (World Bank 2020). As of 2022, the Bank Group used the following description: “Financial inclusion means that individuals and businesses have access to useful and affordable financial products and services that meet their needs—transactions, payments, savings, credit[,] and insurance—delivered in a responsible and sustainable way” (World Bank 2022a).

- See Center for Financial Inclusion’s 2019 Digital Finance Evidence Gap Map (https://www.centerforfinancialinclusion.org/digital-finance-evidence-gap-map) and World Bank 2015a.

- The Global Findex equates the percentage of people who have a mobile money account with the percentage of its survey respondents who reported personally using a mobile money service to make payments, buy things, or send or receive money in the past year.

- The Global Findex is unable to quantify the rural access gap: “But precisely quantifying the urban-rural gap is difficult. Defining what makes an area rural is complex—should the distinction be based on population density, on the availability of certain services and infrastructure, or on the subjective judgment of the interviewer or of the respondent? These definitional issues become more challenging when applied across economies—what might be considered rural in Bangladesh or India, for example, might be considered urban in less populous economies” (Demirgüç-Kunt et al. 2022, 28).

- Reflective of this, the structured literature review found that where disaggregation was possible, the impacts of gender-specific program features focused on women’s empowerment were larger than those of features focused solely on access to financial services (Chliova, Brinckmann, and Rosenbusch 2015; Peters et al. 2016).

- The Independent Evaluation Group identified digital financial services projects based on their use of digital technologies to deliver financial services or their objective to create conditions for the delivery of financial services using digital technologies.

- An estimated 1.3 million Colombians and 28 million Brazilians received new accounts related to government payment initiatives (Qiang, Rutkowski, and Pesme 2022).

- We were unable to verify estimations of the actual achievement of unbanked people who gained access to a transaction account resulting from Bank Group support. For example, the International Finance Corporation estimates that it met or exceeded its goal of enabling 600 million unbanked people to gain access to a transactions account. We could not use the International Finance Corporation’s estimate because it was based on an estimation of the incremental reach indicators in the 25 universal financial access countries that do not explicitly distinguish reach to excluded populations. Instead, to estimate the number of excluded people reached by its portfolio, the International Finance Corporation used the Global Findex–based country percentage of excluded population. We could not find the rationale to assume that this proportion should match the clientele of supported financial institutions and services.

- We did not directly evaluate the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor, but its use and role in Bank Group financial inclusion work emerges in inputs such as country case studies.