Addressing Gender Inequalities in Countries Affected by Fragility, Conflict, and Violence

Chapter 3 | Getting to Results

Highlights

The World Bank Group has strengthened elements of transformational change in projects related to gender-based violence and women’s and girls’ economic empowerment, but these project designs still have limitations.

The Bank Group has improved project designs in later project phases or follow-on projects. This happened when projects applied lessons from previous projects to new designs, planned for increased women’s participation in project activities and better addressed their needs and constraints in the new project designs, focused more on improving the country’s enabling environment, built local actors’ capacity, and coordinated better with and among stakeholders.

Since 2019, the Bank Group has approved innovative fragility, conflict, and violence–focused projects that address both impacts and drivers of fragility, conflict, and violence, thus easing the trade-off between humanitarian and development goals. These projects adopt decentralized, community-based, and inclusive approaches to build peace and resilience.

The Bank Group’s country engagement generally uses a project-centric approach that pursues gender goals through individual and disconnected projects. This approach rarely defines long-term, overarching women’s and girls’ economic empowerment, gender-based violence, or gender equality goals and exacerbates project-level trade-offs.

The Bank Group’s analytical products vary in quality and do not provide a deep and consistent analysis of the relationships between gender inequalities and fragility, conflict, and violence issues. This is especially apparent in analytical work that influences country strategies.

Monitoring and evaluation frameworks do not adequately measure transformational change processes or outcomes at either the project or the country level. This makes it difficult to systematically document what gender results the country engagements achieve and what gender-related interventions work.

This chapter analyzes the evolution of the Bank Group’s support for WGEE and for GBV prevention and response in FCV-affected countries and discusses pathways and challenges to achieving better results. The chapter focuses on three areas: (i) the recent evolution of Bank Group support for WGEE and for GBV prevention and response in FCV countries, which shows improvements in the design of many projects that moved from initial to later phases, and the emergence of a new generation of innovative projects focused on FCV; (ii) the Bank Group’s difficulties in shifting from a project-centric to a strategic country engagement approach as the pathway to achieve transformational change; and (iii) the limitations of the Bank Group’s current monitoring and evaluation frameworks in capturing outcomes and transformational change in GBV and WGEE. The chapter argues that there have been improvements at the project level, but the Bank Group’s focus on individual projects is limiting. Shifting from a project-centric to a strategic country engagement approach can allow the Bank Group to ease some of the trade-offs discussed in the previous chapter and better support FCV-affected countries in achieving WGEE and preventing and responding to GBV.

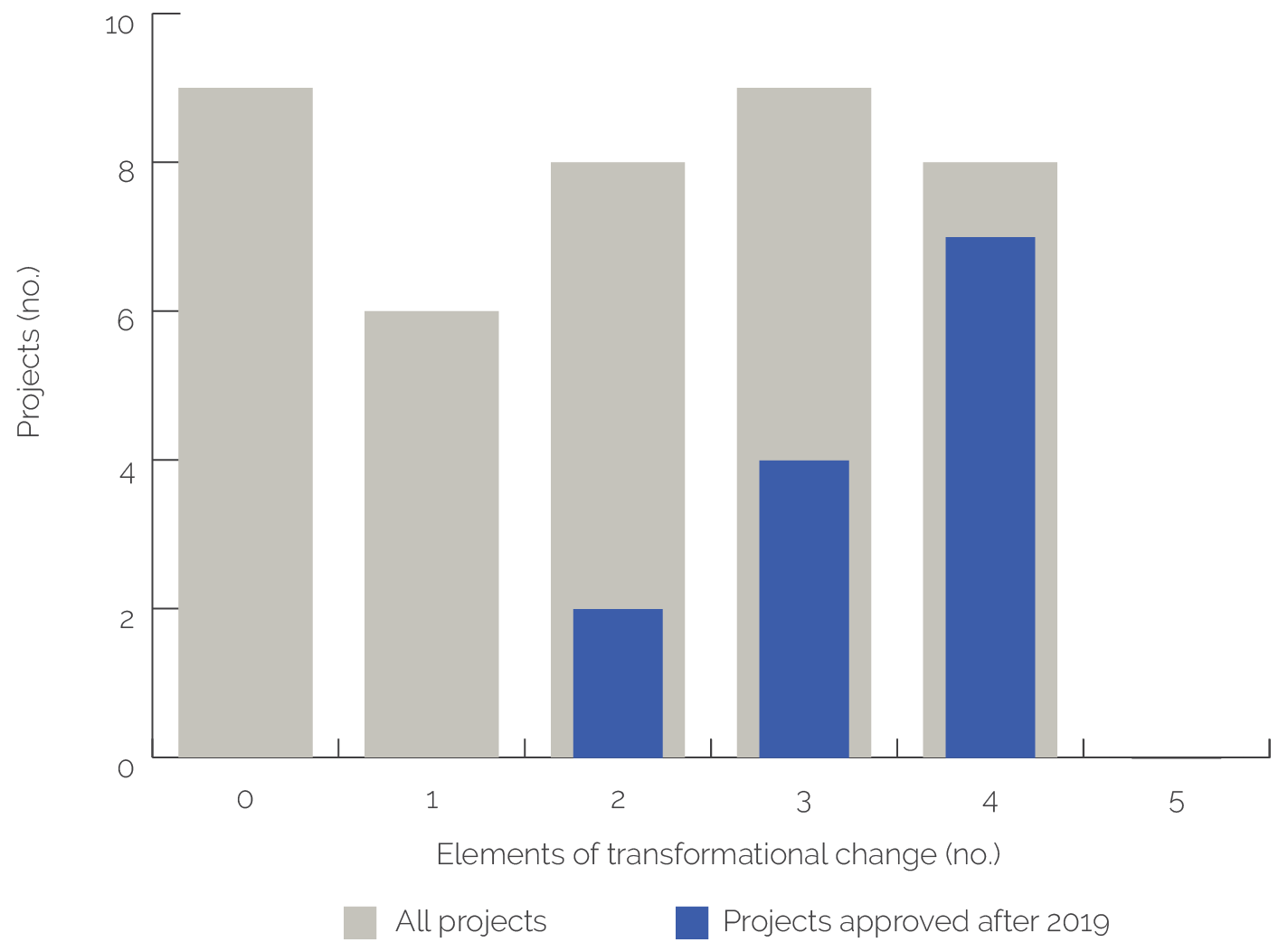

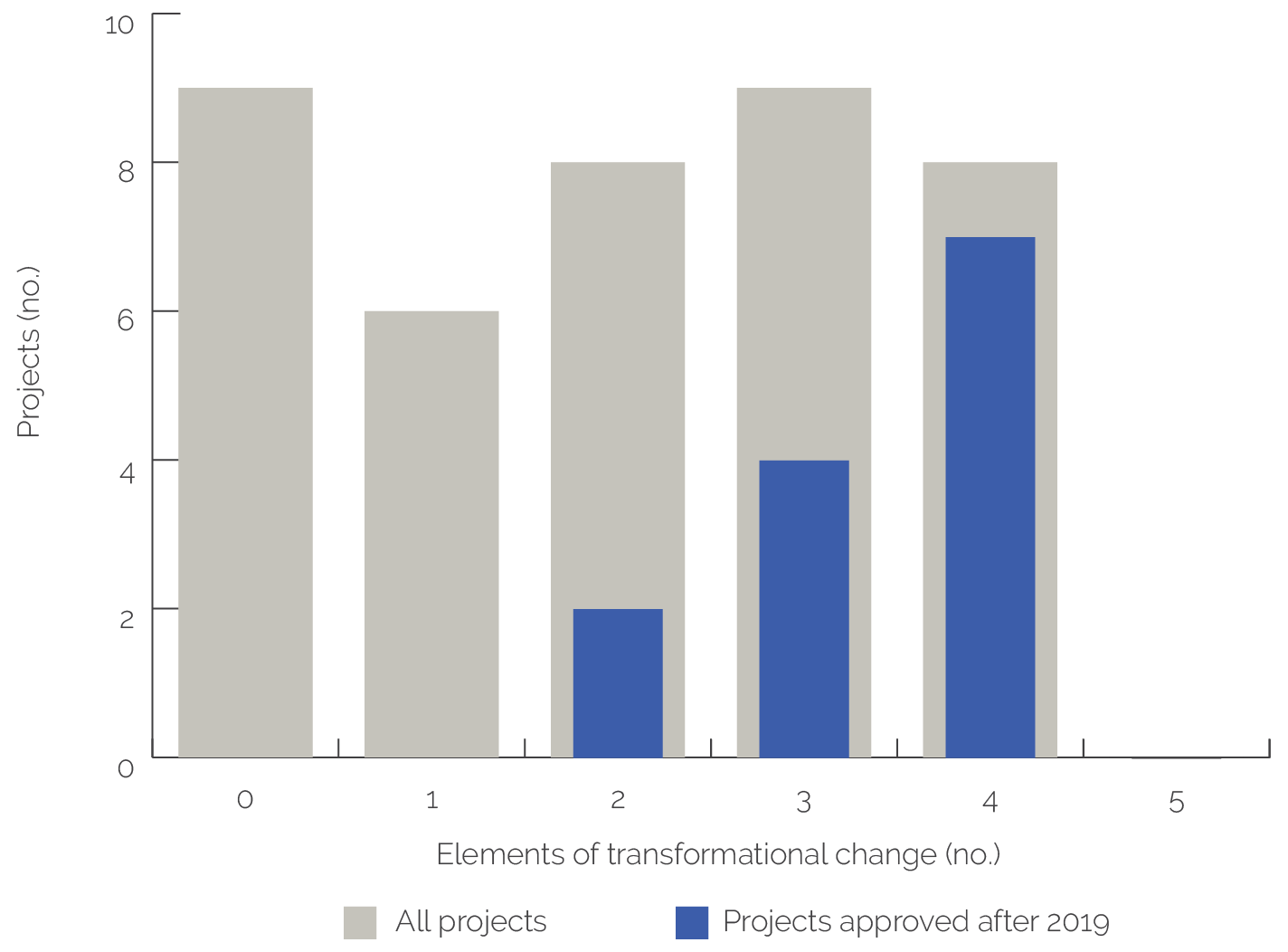

Recent WGEE- and GBV-related projects have a greater transformational potential compared with older projects. Thirteen of the 41 project designs analyzed for this evaluation were approved in 2019 or later, and of those, 11 have at least three elements of transformational change (figure 3.1). Six of the 11 projects are follow-on phases from previous projects, whereas 5 are entirely new projects. Moreover, 7 of the 8 projects with four transformational elements are recent. This shows that the Bank Group has applied lessons learned from previous projects to new designs in the same country or others.

Figure 3.1. Elements of Transformational Change for All Projects Compared to Recent Projects

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Learning from Implementation to Improve Results

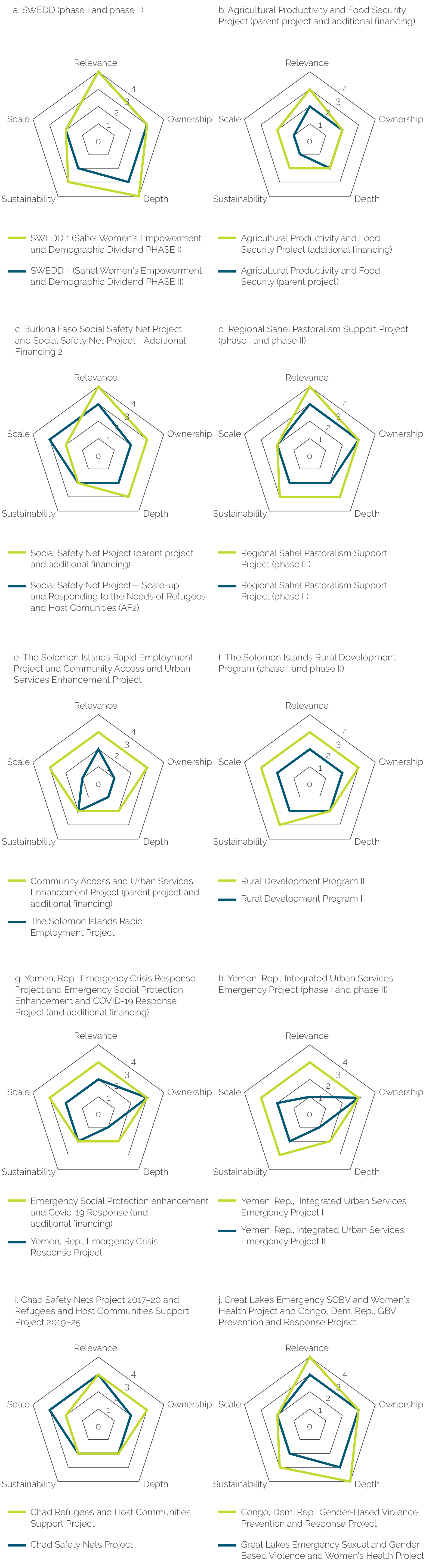

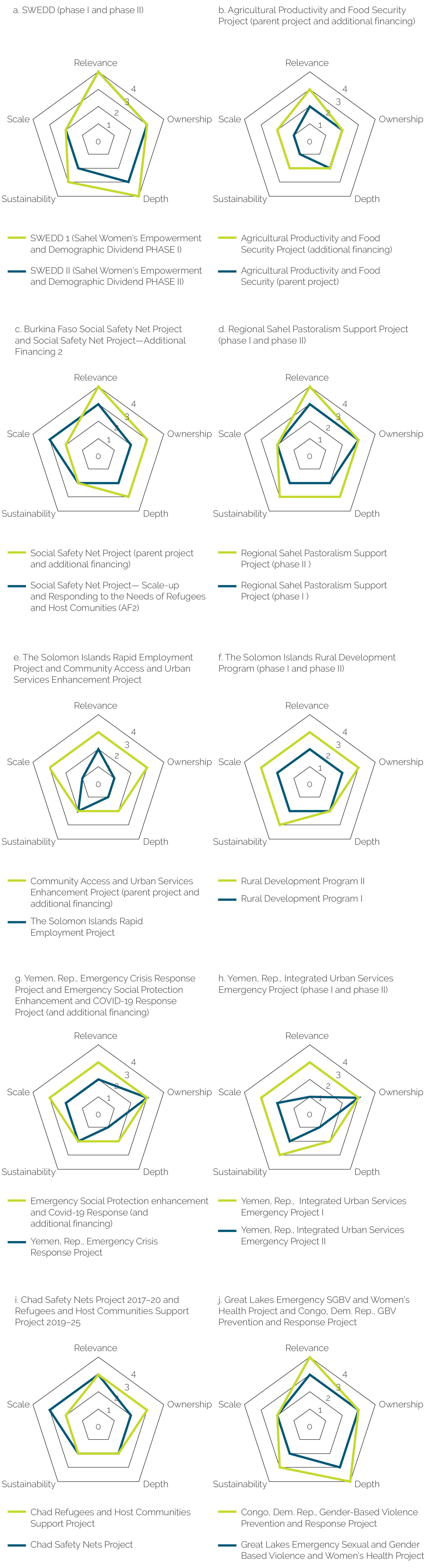

Project design improved over the evaluation period. Figure 3.2 shows that 10 of the case study projects improved the initial design (phase I) in a follow-up project (phase II) or additional financing design. All analyzed project designs were below full transformational potential (a maximum score in all elements), but in all 10 cases there were improvements in most elements from one phase to the next. These improvements were made possible by (i) using assessments and lessons from the previous project’s implementation, (ii) using gender expertise to address gaps in design, (iii) increasing budget allocations for WGEE and for GBV prevention and response, and (iv) ensuring project continuity, flexibility, and timely adaptation. Some of these factors will be discussed in detail in chapter 4.

Figure 3.2. Evolution of Project Design in Select Projects

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The blue (darker) line marks the score of the transformational elements in the early-phase project; the green (paler) line in the second-phase project. Project rating criteria are described in detail in appendix A. GBV = gender-based violence; SGBV = sexual and gender-based violence; SWEDD = Sahel Women’s Empowerment and Demographic Dividend.

Projects increased relevance and depth by addressing shortcomings in the original design. For example, the GBV Prevention and Response Project in the Democratic Republic of Congo built on lessons from the earlier regional Great Lakes Project. The earlier project included activities to prevent GBV and meet GBV survivors’ needs but did not include any specific strategy for GBV prevention, had a limited scope and outreach effort, and included communication campaigns that were too short to produce any significant change. In response, the Democratic Republic of Congo project integrated a stronger component of GBV prevention that mobilized the community and adopted tested approaches, such as Start, Awareness, Support, and Action and Engaging Men through Accountable Practice,1 to transform gender norms, improve GBV reporting, and reduce GBV survivors’ stigmatization. The project provided gender-transformative training to community activists who would manage cases, refer survivors to services, and mobilize community leaders to prevent GBV. Another example is the Regional Sahel Pastoralism Support Project covering Chad and Burkina Faso. The project’s Mid-Term Review recommended undertaking a gender assessment, which identified design shortcomings and recommended strategic investments in women’s income-generating activities (which, in Chad, had not been prioritized) and increased gender accountability and awareness at all levels (a more comprehensive approach than in the original design). Building off the Mid-Term Review, the project’s phase II integrated a new stand-alone component to support youth and women’s income-generating activities, improve the monitoring and evaluation framework, and “institutionalize” gender based on a gender action plan that included a stronger strategy for gender training and sensitization and added female participation quotas in consultation meetings and management committees.

In some cases, projects increased relevance and depth by integrating measures to increase women’s participation. Projects that did not pay sufficient attention to the constraints to women’s participation ended up with a lower-than-expected share of female beneficiaries. For example, in the initial phase of the Burkina Faso Agricultural Productivity and Food Security Project, women made up only 9.6 percent of the farmers recruited for training and 20 percent of the recipients of credit under a warrantage system. To address these shortcomings, the follow-on project mandated that 30 percent of project beneficiaries be women. To ensure that this quota was fulfilled, the project provided training to implementing partners and stakeholders, including farmers’ organizations, in Socio-economic and Gender Analysis.2 Because of greater stakeholder capacity in participatory gender analyses and planning, women’s participation in the trainings increased to 34 percent (Sawadogo-Kaboré et al. 2020).3

Projects also increased their relevance by introducing activities to address gender inequalities faced by FCV-affected women and girls. The second additional financing of the Social Safety Net Project in Burkina Faso, for instance, increased social safety nets and broadened their target beneficiaries to refugees and host communities. The design of the additional financing incorporated lessons from the previous Youth Employment and Skills Development Project by enhancing FCV-affected women’s economic empowerment through cash transfers, skills development, and labor-intensive public works activities supplemented by childcare support. It also included a new component of community-based prevention of child marriage and other forms of GBV.

The new SWEDD project design increased relevance and depth by improving coordination among activities and project stakeholders. During the project’s first phase, the SWEDD’s complementary subcomponents were spread out among different geographical areas within the project countries—essentially, the theory of change was “broken down,” which decreased the project’s overall effectiveness, because of the weak strategic and operational coordination among the implementing partners in the different regions. The project’s second phase aims for stronger coordination among the implementing partners and establishes mechanisms to layer and connect the various pieces of the theory of change within the same localities. This would ensure that multiple interventions—for example, men’s and boys’ clubs, activities to support WGEE, and activities to improve sexual and reproductive health services—complement each other and operate together, rather than in isolation.

Projects strengthened sustainability and scale in three ways—consolidating results, developing local capacity, and improving the enabling environment. For example, both the SWEDD and the Great Lakes Project improved sustainability by consolidating results from the first phase to the second. The Democratic Republic of Congo GBV Prevention and Response Project design, which followed up the initial Great Lakes Project, consolidated the GBV case management component from the first project by helping implementing partners develop their sustainability plans, improve the referral system, and build the capacity of CSOs, public health service providers, and community-based organizations in GBV prevention. Nevertheless, the project still lacks a strategy to ensure its financial sustainability after the project closes. The SWEDD’s project managers learned from SWEDD’s first phase that they needed to improve the enabling environment to support WGEE and prevent GBV. To this end, the SWEDD II plans to create a regional legal platform to improve the country’s legal framework,4 increase the integration of the demographic dividend in the state budget and develop regional and national referral pathways for GBV survivors to access legal, medical, and socioemotional support.

The World Bank occasionally used impact evaluations to improve project designs. Two projects that used impact evaluations to inform their theories of change were the Great Lakes Project in the Democratic Republic of Congo and the SWEDD I in the Sahel. Both used the evidence from impact evaluations of projects from other countries to justify holistic approaches to support GBV survivors in the Democratic Republic of Congo and promote women’s and girls’ empowerment and reduce child marriage in the Sahel. The Social Safety Net projects in the Sahel also benefited from impact evaluation evidence (and were themselves impact evaluated) under the Sahel Adaptive Social Protection Program, a multidonor trust fund supporting evidence-based design and adaptive social protection systems in the Sahel.5 Outside social safety nets, the World Bank almost never used impact evaluations to develop the theories of change of women’s economic empowerment interventions.6 Some projects—such as the Social Safety Net projects in Chad, Burkina Faso, and the Republic of Yemen and the GBV-focused interventions in the Democratic Republic of Congo—were evaluated to inform subsequent project phases. However, the World Bank was not always able to use those evaluations because of misaligned timelines. For example, the impact evaluation of the SWEDD I was meant to inform the second phase, but the SWEDD II was designed and started before the conclusion of the impact evaluation.

Since 2019, the World Bank Group has introduced projects that use decentralized and community-based approaches to address FCV, support WGEE, and counter GBV. Many of these new projects address the impacts and drivers of FCV, such as conflict and climate change, and explicitly confront both sides of the humanitarian-development nexus. They do so by adopting decentralized and community-based approaches that target FCV-affected populations, such as forcibly displaced people, host communities, and populations living in open conflict areas. According to the literature, these approaches enable more inclusive mechanisms of governance that empower women and girls and other marginalized groups and improve the accountability and capacity of local institutions to address FCV’s impacts and drivers (Atuhaire et al. 2018; Bojicic-Dzelilovic and Martin 2018; Cislaghi 2019; Gupta et al. 2020; Interpeace 2020; UN and World Bank 2018). For example, Burkina Faso’s 2021 Emergency Local Development and Resilience Project, which has WGEE and GBV components, used consultations with women’s organizations to identify and prioritize needs and mobilize communities to prevent GBV, through safe spaces for women’s and girls’ skills development, men’s and boys’ engagement, and initiatives of community dialogue to change gender norms. In Chad, the Lake Chad Region Recovery and Development Project aims to engage regional and community stakeholders to forge “partnerships between humanitarian and development actors” (World Bank 2020e, 23). The project helps communities identify, implement, and monitor community development plans and apply a gender-sensitive approach. It also helps local authorities integrate project activities in municipal development plans.

Some new projects enhanced their support for preexisting initiatives and local actors to promote sustainability. These projects built on ongoing local processes and developed the capacity of local actors to generate change leading to sustainable results. For example, in Chad, the ALBIA, which promotes women’s economic empowerment, builds the capacities of the communities’ female leaders, supports preexisting women’s groups and their economic activities, raises the gender awareness of local authorities and religious leaders, and improves the gender responsiveness of existing agriculture extension services and local communal development plans. Likewise, the Lake Chad Region Recovery and Development Project plans to build the capacity of local authorities, community institutions, and community-based organizations, including women’s groups, to ensure they can sustain project results. The community-led initiatives will be integrated into the existing communal development plans.

Shifting from a Project to a Country Focus

Shifting from a project-centric approach to a strategic country engagement on gender equality would ease the trade-offs discussed in chapter 2. The Bank Group focuses most of its support for WGEE and for GBV prevention and response on individual projects rather than country engagements (which combine many activities and pursue high-level gender equality goals over a long period). This project-centric approach does not correspond to the mandate of the organization, which centers on the country engagement model: “the Bank Group supports client countries to end extreme poverty and boost shared prosperity in a sustainable way, by contributing over time to high-level outcomes, consistent with a country’s development goals” (World Bank Group 2014). As we have seen, the intensity of some elements of transformational change has improved in recent projects, but even so, these projects do not achieve their full transformational potential and doing so is out of the reach of individual projects. However, the evaluation found that the Bank Group’s country engagement on gender equality issues remains highly focused on delivering individual projects and that these projects are not part of a comprehensive and long-term strategic approach to gender. Projects cannot trigger transformational change for WGEE and GBV and contribute to high-level outcomes if they are self-contained and not woven into a longer-term strategic perspective, likely covering multiple country strategies. IEG’s meso-evaluation Social Contracts and World Bank Country Engagements: Lessons from Emerging Practices observed that redefining power relationships—whether renewing social contracts or addressing the root causes of gender inequalities—requires a long-time horizon that “does not fit into shorter-term country programs and lending instruments” (World Bank 2019c, 28).

A project-centric approach has limitations in terms of the depth, sustainability, and scalability of Bank Group support for WGEE and for GBV prevention and response. Individual projects cannot produce changes in GBV and WGEE that are simultaneously deep, sustainable, and large-scale because these changes require continuity over a long-time horizon, integrated and multisectoral approaches, and collaboration among a country’s development partners. This evaluation’s interviews and desk analysis corroborate the findings of IEG’s Mid-Term Review, which indicated that “closing country gender gaps is beyond the scope, budget, and timeline of a single project[;] fully addressing gender gaps takes sustained effort, spans multiple projects, and can be addressed more strategically using Bank Group instruments collectively” (World Bank 2021f, 28). The SWEDD project, for example, uses a multisector approach and multiple entry points to increase access to sexual and reproductive health services and empower women and girls. According to key informants, however, the costs of bringing the SWEDD’s complex design to a national scale would be prohibitive. A more viable option to expand the SWEDD’s approach consists of collaborating with other development partners to connect each one’s gender equality program. The SWEDD has decided to follow this option and has recently started a collaboration with the French Development Agency to socialize its approach. Another strategy would be to identify which SWEDD elements were successful and graft them onto the World Bank’s large sector programs, which are already at scale or more easily scalable. Both approaches require the Bank Group to go beyond the project-by-project approach and explore connections and potential synergies across its own and others’ projects to follow a long-term strategic direction.

The Systematic Country Diagnostic (SCD)–Country Partnership Framework (CPF) model in the six analyzed FCV countries does not include an explicit long-term approach for addressing gender inequalities in those countries. The SCD and CPF are core elements of the Bank Group’s country engagement approach that outline the Bank Group’s strategy in any particular country. Only 5 of the 16 country strategies analyzed for this evaluation include gender-related objectives or subobjectives. Two of these five strategies include unclear or unspecific objectives. For example, the Democratic Republic of Congo CPF (2022–26) includes an overly broad objective to “improve gender disparities and inclusion across sectors” (World Bank 2022d, 26). When it comes to WGEE and GBV, only one old country strategy (the FY11–14 Country Partnership Strategy for Lebanon) includes a subobjective explicitly related to WGEE, whereas none of the strategies include an objective or subobjective on GBV.

It is rare for country strategies to define how various activities in the country portfolio combine to achieve higher-level goals related to WGEE or GBV. A gender-specific objective or subobjective in a country strategy identifies priority gender-related issues and can orchestrate the use of various instruments, including analytics, operations, and technical assistance, toward achieving specific goals. However, the evaluation found this in only one case. Lebanon’s 2010 Country Partnership Strategy specified improving women’s access to finance as a subobjective and brought together different elements of a strategic approach to achieve that objective (World Bank 2010). The country strategy aimed to improve the enabling environment through technical assistance to review and amend the labor code, assess women’s job informality and insecurity, and support women-owned businesses through IFC initiatives. This focus was somewhat lost in Lebanon’s 2016 CPF, which maintained some emphasis on WGEE through planned analytical work but did not have a specific objective on women’s access to finance (World Bank 2016c). This may be why the CPF’s results framework did not include indicators on women’s economic participation.

In several cases, country strategies do not explicitly articulate the contribution of projects to WGEE and to GBV prevention and response in the country. For instance, the Chad country program carried out an assessment of social safety nets that described women’s vulnerability to poverty and fragility and indicates women’s economic empowerment as a source of resilience (World Bank 2016d). The country program also included lending for social safety nets and planned the regional Sahel Adaptive Social Protection Program. These programs are listed in Chad’s CPF as items in the country portfolio, but their synergetic contribution to the economic empowerment of vulnerable women is not discussed.

The focus of country strategies on GBV and WGEE, when it exists, is easily lost from one strategy to the next. This discontinuity makes it difficult to connect individual projects to others over the long term. Figure 3.3 shows the discontinuity of WGEE and GBV across two subsequent country strategies for the six countries analyzed. We see that a focus on WGEE is more frequent and more commonly maintained or strengthened from one country strategy to the next compared with GBV. For example, in Burkina Faso, the 2013 Country Partnership Strategy discussed the need to bring women into a more active role in the economy (World Bank 2013a). Meanwhile, the 2018 CPF expanded this intent by also highlighting women’s systematic disadvantages in the labor market and calling for support to women-owned farms and businesses (World Bank 2018a). By contrast, GBV had not been introduced or was only recently introduced in three of six country strategies. In the Solomon Islands, the scope for decreasing GBV in the 2013 strategy (World Bank 2014c) was narrowed down to just providing GBV safeguards in the 2018 country strategy (World Bank 2018h). Moreover, in cases where country strategies consistently focused on a specific theme, they did not go deep in advancing that theme in subsequent strategies. Likewise, the Republic of Yemen’s consecutive Country Engagement Notes FY20–21 (World Bank 2019b) and FY22–23 (World Bank 2022c) emphasized the importance of providing psychosocial support to GBV survivors, but none discussed plans to operationalize that support.

Figure 3.3. Gender Inequality Focus Areas in Subsequent Country Strategies

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

The analytical work that influences country strategies does not adequately explore the interplay between gender inequalities and FCV issues. Gender-focused analytical products are more likely to provide a comprehensive in-depth analysis of gender in FCV settings than strategic analytical products. Some recent gender assessments provide great insights into how fragility exacerbates gender inequalities and how gender inequalities can contribute to fragility. For example, the Lebanon gender assessment (World Bank and UN Women 2021) analyzes female labor force participation and women’s access to services, by refugee status and vulnerability level, and shows that the country’s multiple crises have aggravated Lebanese women’s difficulties in generating income and improving their livelihoods (see box 4.3). Likewise, the Chad gender assessment (World Bank 2020a) examines the relationship between gender inequalities and demographic pressures, a key fragility driver, and also analyzes the gendered impacts of COVID-19. However, the influence of these in-depth gender and FCV analyses is not evident in SCDs and CPFs. Poverty assessments and social protection reports may have a more immediate impact on strategy, but are notably silent on the interactions between gender and fragility. For their part, poverty assessments tend to limit their analysis to the poverty gaps between male-headed and female-headed households despite the abundant research that documents gender inequalities in the intrahousehold allocation of resources (Behrman 1988; Brown, Ravallion, and van de Walle 2019; Hoddinott and Haddad 1995; Thomas 1994).7 Moreover, many poverty assessments do not explore the gendered impacts of fragility. For example, the 2021 Chad Poverty Assessment: Investing in Rural Income Growth, Human Capital, and Resilience to Support Sustainable Poverty Reduction (World Bank 2021a) describes the higher poverty rates for Central African and Sudanese refugees than for the rest of Chad, but does not provide any sex-disaggregated information. Similarly, the social protection reports for the Republic of Yemen (World Bank 2018d) and Burkina Faso (Vandeninden, Grun, and Semlali 2019) do not focus on the gendered impacts of social protection programs, despite recognizing that women are particularly vulnerable to crises.

Risk and Resilience Assessments (RRAs) increasingly discuss gender inequalities, especially the links between FCV and GBV. Eight of the nine analyzed RRAs discuss these links, and four identify gender equality as a source of resilience. For instance, the Sahel RRA (World Bank 2020c) frames demographic pressure as a key driver of fragility and gender inequality in the region. Similarly, the Democratic Republic of Congo RRA (World Bank 2021b) highlights sexual and gender-based violence as eroding social cohesion. Likewise, the Solomon Islands RRA (World Bank 2017e) shows how the social and economic costs of gender inequalities exacerbate the country’s fragility. In other examples, the Chad RRA (World Bank 2021d) discusses the steep increase in GBV by state and Boko Haram factions; the Democratic Republic of Congo RRA (World Bank 2016b) explores the relationship between GBV and violent masculinities in situations of conflict; and the Republic of Yemen RRA (World Bank 2022i) highlights the susceptibility of vulnerable groups, such as IDPs, to GBV. It is still too early to know if these RRAs will stimulate a greater focus within country strategies and operations on the most important gender inequalities—that is, if these RRAs will make strategies and projects more relevant.

SCDs increasingly recognize the interlinks between gender issues and fragility, but only in a few cases do their analyses relate to local FCV contexts. Five of the six SCDs examined for this evaluation discuss the interplay between GBV and FCV, and four of six analyze constraints to WGEE. By contrast, SCDs do not account for the local FCV context or enabling environment. The Democratic Republic of Congo SCD (World Bank 2018f) is an exception; it emphasizes the acute GBV challenges for vulnerable women, such as IDPs and women with disabilities, in the context of a country’s patriarchal norms, laws, and policies. Nevertheless, SCD analyses tend to be more coherent, relevant, and context specific when informed by RRAs. This was the case for the Chad SCD (World Bank 2022a), which discusses the impacts of the country’s legal framework on GBV.

The Bank Group’s gender-focused engagement with development partners and other nonstate actors is also centered on projects. When asked about the Bank Group’s role in coordinating and leading partnerships on gender, 79 percent of Bank Group staff and implementing partner informants cited only projects as examples of collaboration and partnerships. Several Bank Group interviewees stated that it was only within “the framework of a project” that they coordinated with relevant stakeholders. Specifically, Bank Group staff discussed collaborating with implementing partners, cofinancing donors, and other project stakeholders but rarely mentioned collaborating with partners on policy dialogues or the creation of synergies between different initiatives. One Bank Group staffer stated that, outside of the project, “there is a level of communication, not coordination.” Another Bank Group staffer stated that “it is more of an exchange of information.”

Measuring Results

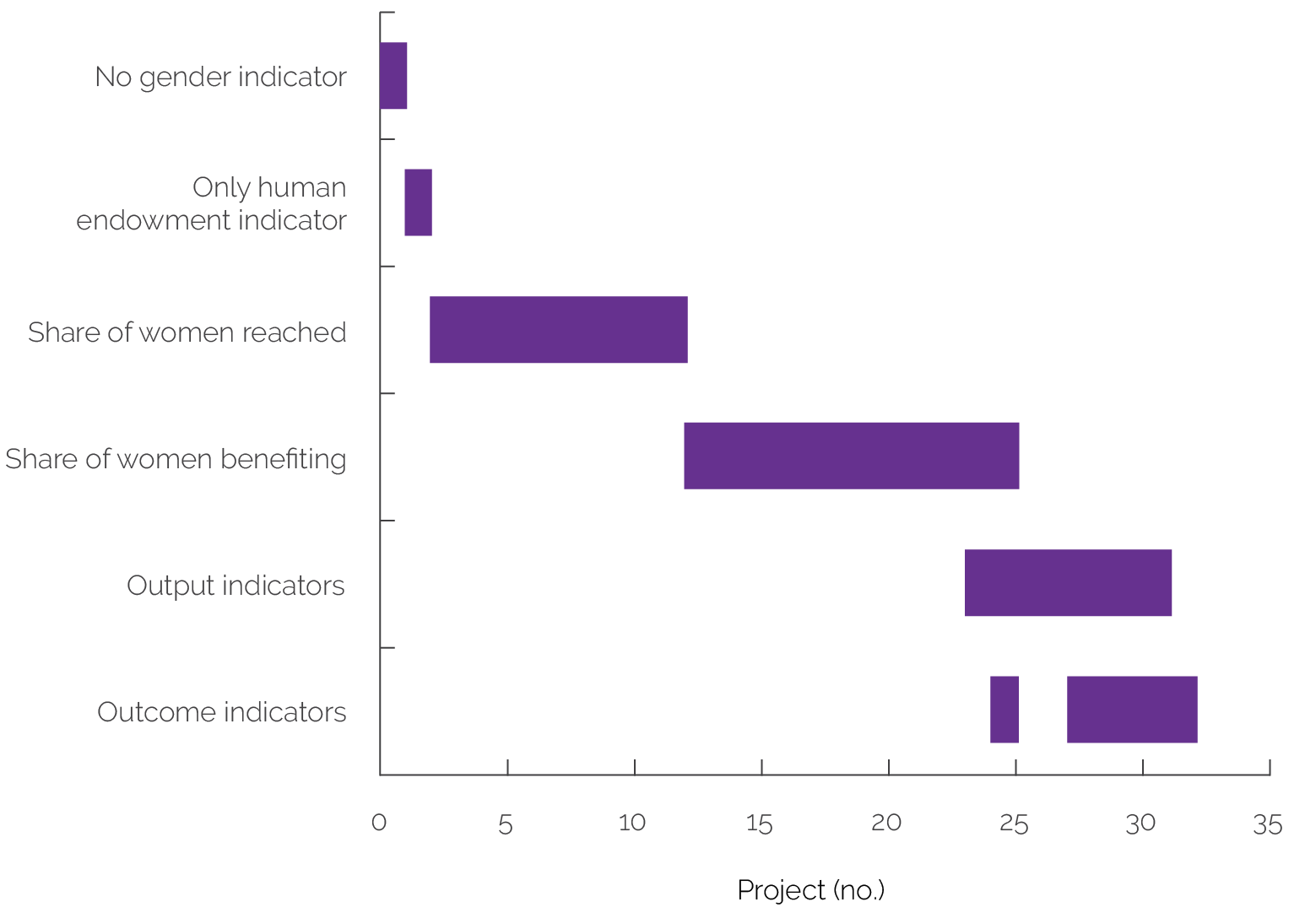

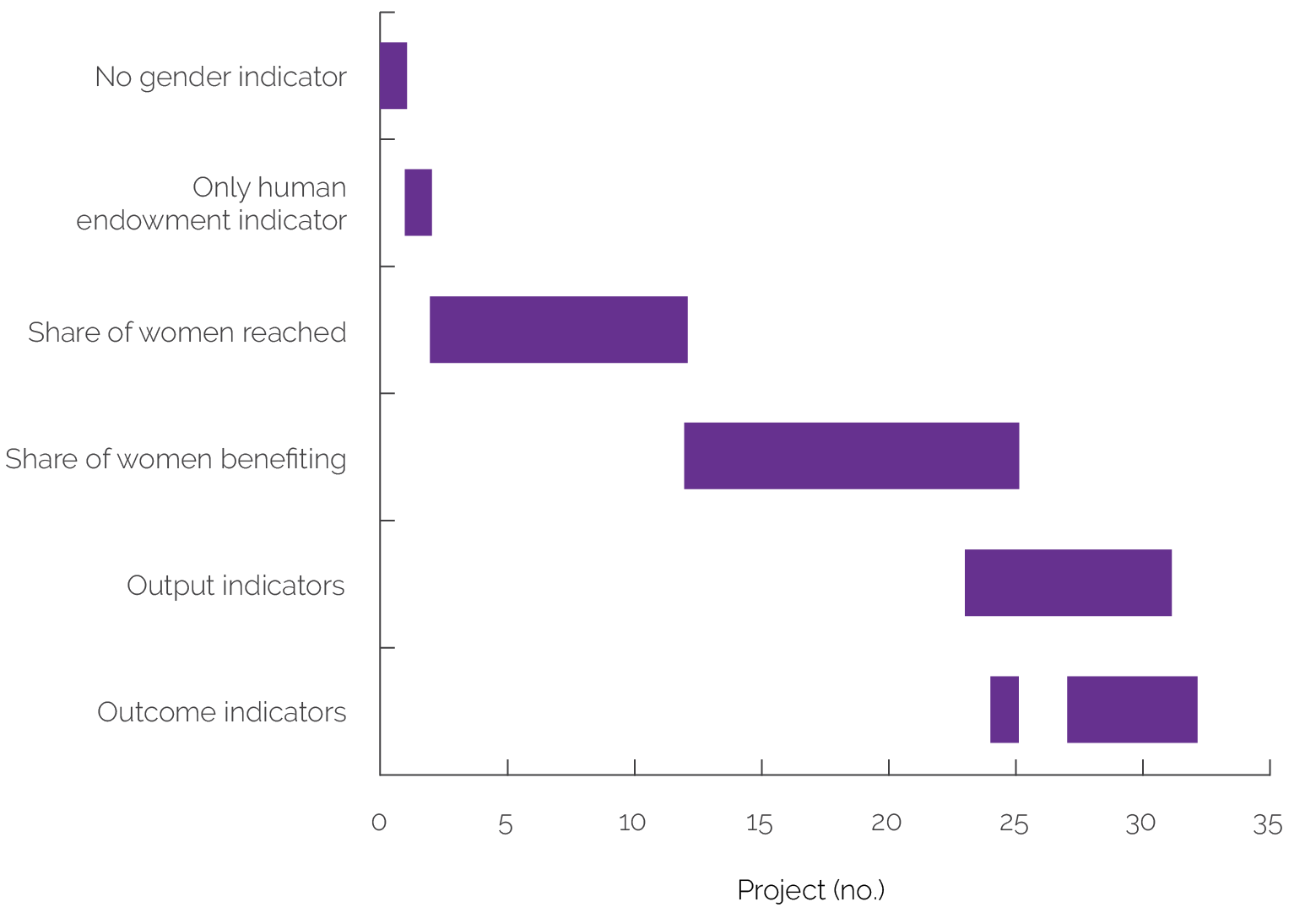

Monitoring and evaluation frameworks are also project-centric and have drawbacks that prevent them from measuring transformational change. There is not much evidence on the results of efforts to achieve transformational change. This is partly because many GBV and WGEE projects are new but also because monitoring systems of both new and older projects do not adequately capture results of transformational change elements in GBV and WGEE. Several key informants expressed the view that “quantitative data on women’s participation in project activities” was key to the monitoring process, and yet two-thirds of analyzed projects do not include indicators that measure outcomes related to GBV or WGEE. Of the 32 analyzed projects,8 30 have at least one gender-relevant indicator.9 Of these, 10 projects measure only the share of women or girls whom the project reaches, and another 11 projects measure only the share of women or girls who benefit from an element of the project (figure 3.4). Projects with stronger monitoring and evaluation frameworks report sex-disaggregated outcome data—for example, the percentage of women employed after a job training program or the net enrollment rate of girls, instead of just the share of female beneficiaries in project activities.

Project monitoring and evaluation does not adequately measure progress in WGEE and in GBV prevention and response, despite improvements. The monitoring and evaluation framework of the SWEDD II, for example, is stronger than that of the SWEDD I because, as discussed above, it measures GBV case management and changes in the enabling environment.10 However, even the stronger monitoring and evaluation frameworks have limitations. For example, an indicator measuring the number of legal frameworks that support girls’ education and adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health does not capture the actual goal, which is to improve those frameworks. Nor does an indicator measuring the number of GBV cases that are supported by a project capture improvements to the GBV referral system. In Chad, the ALBIA includes an intermediate indicator on women’s economic empowerment—the percentage of women within the project reporting increased incomes from extension services; however, it does not measure the project’s achievements relative to the target geographical area or the country’s underserved population.

Figure 3.4. Prevalence of Indicators Related to WGEE and Gender-Based Violence in Analyzed Monitoring and Evaluation Frameworks

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Only World Bank projects are included because the monitoring framework of International Finance Corporation projects is not fully comparable. WGEE = women’s and girls’ economic empowerment. The figure indicates how many projects have which type of indicators (also showing projects that have different types of indicators at the same time). For example, one project has share of women benefiting, output indicators, and outcome indicators; four projects have output indicators and outcome indicators.

Measuring the share of female beneficiaries does not indicate the results of the intervention. There are three reasons for this. First, counting beneficiaries is often misinterpreted; it measures outreach, not the positive impacts from the intervention. Second, setting target shares of female beneficiaries is typically based on what the project can provide, not based on the needs of women and girls. In addition, setting quotas relative to the project’s capacity rather than to the country’s needs may result in paradoxically setting minimum targets that are below the number of women whom the project will attract. This was what happened with Burkina Faso’s Youth Employment and Skills Development Project, which attracted more women to its public works component than the original quota mandated (64 percent of women among the youth participating in public works compared with 30 percent of women who were expected to participate). According to a qualitative evaluation (Grun et al. 2021) and key informant interviews, high female underemployment rates and the public works’ low salaries made these jobs particularly appealing to young women but unappealing to young men. Third, in isolation, the share of female beneficiaries does not measure improvements in women’s situations in either absolute or relative terms, even if it successfully measures the share of women who were economically empowered by the intervention.

Output and outcome indicators are, in most cases, weak measures of transformational change, even when they are related to WGEE or GBV. Six of the 32 analyzed projects have outcome indicators, and eight have output indicators that capture changes in WGEE and GBV (figure 3.4) or, in a few cases, measure improvements in service providers’ capacity or other aspects of the enabling environment for WGEE and for GBV prevention and response. In most cases, these indicators do not measure elements of transformational change. Many project development objectives are output (not outcome) indicators that do not measure changes in WGEE or GBV. Moreover, indicators are frequently defined in relation to the project, not to the national, subnational, or local context. Projects usually measure results in relation to a zero baseline (that is, they measure their absolute contribution) rather than benchmarking the project’s contribution against the needs of the communities or service gaps.

The paucity and inadequacy of indicators to measure processes and results partly reflect the lack of involvement of women and other relevant actors in monitoring and evaluation. The evaluation did not find examples of participatory monitoring—an activity that involves communities in choosing, collecting, and reporting meaningful indicators, which can be more easily identified by direct beneficiaries than nonlocal planners. For example, the experience of self-help groups in India, documented by the Social Observatory,11 has shown that involving women in defining poverty indicators leads to more meaningful indicators that reflect what communities truly feel contributes to their well-being (Ananthpur, Malik, and Rao 2014).

Results frameworks in country strategies reflect the project-centric approach and do not measure transformational change in WGEE and GBV. The nine reviewed country strategies that have a results framework include gender-related indicators—development outcomes and intermediate results—that are lifted from individual projects. These indicators most frequently measure project-level gender results—that is, they measure what the project did for the country (table 3.1, section a), not the country’s progress toward achieving gender equality, WGEE, or GBV prevention and response (table 3.1, section b). Moreover, eight of nine country strategies include the percentage or number of female beneficiaries as an indicator (table 3.1, section c), which is also a project-level indicator. Only the Solomon Islands Country Partnership Strategy (2013–17) had a country-level gender indicator (table 3.1, section b), and specifically a GBV indicator (World Bank 2013c). These country strategy results frameworks more commonly measured gender-related human capital indicators, such as female access to health and education (the “Other” columns in table 3.1), but less commonly measured WGEE and, especially, GBV, even at the project level.

Impact evaluations measured the impact of specific interventions but were normally disconnected from other types of evaluation that could have provided a deeper and broader perspective on results. Twelve relevant impact evaluations were produced for seven projects, almost all in Human Development in Sub-Saharan Africa.12 These impact evaluations measured the impact of specific interventions within a project and have contributed to replicating successful interventions in other projects. For example, impact evaluations of activities of earlier projects informed new project designs, replicating a component that provides cash to women for improved nutrition and holistic support for GBV survivors in the Republic of Yemen or in the Start, Awareness, Support, and Action approach to prevent GBV in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The results of these impact evaluations have also facilitated the Bank Group’s government dialogues and helped motivate certain government interventions, such as the Social Safety Net Project in the Sahel. One weakness of impact evaluations is that they often focus on very specific or small components of much more complex interventions and have trouble measuring the combined impact from the various elements of the project’s theory of change. For this reason, impact evaluations are most useful when they evaluate the impact of multiple layered activities in the same locality or when they are complemented by other types of evaluations.

Table 3.1. Types of Gender-Relevant Indicators Used in Country Strategies

|

Country Strategy |

Other Project-Level Indicators (a) |

Country-Level Indicators (b) |

Percentage of Female Beneficiaries (c) |

||||||

|

GBV |

WGEE |

Other |

GBV |

WGEE |

Other |

GBV |

WGEE |

Other |

|

|

Burkina Faso 2013 |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

✓ |

.. |

.. |

.. |

|

Burkina Faso 2018 |

.. |

✓ |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

✓ |

|

Chad 2016 |

.. |

.. |

✓ |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

✓ |

|

Congo, Dem. Rep. 2014 |

.. |

.. |

✓ |

.. |

.. |

✓ |

.. |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Congo, Dem. Rep. 2022 |

.. |

✓ |

✓ |

.. |

.. |

✓ |

.. |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Lebanon 2011 |

.. |

✓ |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

✓ |

|

Lebanon 2016 |

.. |

.. |

✓ |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

✓ |

|

Solomon Islands 2013 |

.. |

✓ |

.. |

✓ |

.. |

.. |

.. |

✓ |

.. |

|

Solomon Islands 2018 |

.. |

✓ |

✓ |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

✓ |

✓ |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Country Engagement Notes are not reflected in the table because they do not include a results framework. GBV = gender-based violence; WGEE = women’s and girls’ economic empowerment; ✓ = at least one indicator is present; .. = no indicator is present.

- Start, Awareness, Support, and Action (SASA!; “now” in Kiswahili), developed by Raising Voices, is a theory-based approach for mobilizing communities to transform power imbalances between women and men through critical discussion and positive action, with the goal of preventing GBV. The Engaging Men through Accountable Practice approach, created by the International Rescue Committee, is an evidence-based, year-long program to engage men, in humanitarian settings, in individual behavior change to prevent GBV.

- Socio-economic and Gender Analysis is an approach to development based on the analysis of socioeconomic patterns and participatory identification of women’s and men’s priorities. It has been designed and implemented by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and includes (i) the study of the environmental, economic, social, and institutional patterns and the links among them, which constitute the development context; (ii) the study of the different roles of women and men to understand what they do, what resources they have, and what their needs and priorities are; and (iii) a process of communication among local communities and development agents in which local communities take the lead in analyzing the current situation and planning, implementing, and evaluating development activities (FAO 2001).

- The activities planned at additional financing also consolidated and expanded the results achieved in the first phase by continuing to invest in women’s access to lowland, equipment, and the warrantage system.

- The weakness of the SWEDD regional legal platform is its limited inclusive ownership. Key informants of organizations that have historically been engaged in improving the legal framework to promote women’s and girls’ rights in Chad and Burkina Faso reported that they were not involved in this platform (source: interviews with key informants in Chad and Burkina Faso). By contrast, the Mashreq Gender Facility collaborated with other key actors (in particular, UN Women) and successfully supported a process that had been previously initiated by other donors and women’s rights organizations and that led to the adoption of a law on sexual harassment at work.

- One of the focus themes of the program is “Productive Inclusion and Women’s Empowerment.”

- The only exception is the Financial Inclusion Support Project in Burkina Faso, which used the evidence of an impact evaluation conducted in Togo on a very specific activity (personal life skills training for female entrepreneurs.)

- For example, the Chad Poverty Assessment: Investing in Rural Income Growth, Human Capital, and Resilience to Support Sustainable Poverty Reduction (World Bank 2021a) as well as The Independent Evaluation Group World Bank Group 63 Solomon Islands Poverty Profile Based on the 2012/13 Household Income and Expenditure Survey (World Bank Group 2015) and the Yemen Poverty Notes (World Bank 2017g).

- IFC projects were not included in this analysis because their monitoring and evaluation framework is not comparable with the monitoring and evaluation framework of World Bank projects; in particular, the criteria to set indicators differ significantly between the two institutions. Projects are not randomly selected, but as they are mostly gender relevant, these statistics are expected to be much worse for the broader project population.

- The other two projects (not included in these 30) consist of one without gender indicators and one with gender indicators related to access to services and not directly to GBV and WGEE.

- The indicators are the following: number of countries that have adopted budgeting practices that integrate the demographic dividend; number of national and regional legal frameworks that support enrolling and maintaining girls in school, adolescent reproductive health, and the elimination of GBV and harmful practices; and number of GBV and harmful practice cases reported in the project intervention areas that were referred for health, social, legal, and security support according to the referral process in place.

- The Social Observatory is an initiative of the World Bank that supports a $2 billion portfolio for World Bank livelihood projects in India and fosters participatory tracking to empower communities to be equal stakeholders in projects.

- There are only two exceptions of IEs that were not carried out in Sub-Saharan Africa: one impact evaluation of Cash for Nutrition in the Republic of Yemen and one in the Solomon Islands. This latter study is marginally relevant because it does not concern GBV or WGEE, but women’s participation and agency in community management committees of a Rural Development Program. Exceptions = not of Sub-Saharan Africa.