Addressing Gender Inequalities in Countries Affected by Fragility, Conflict, and Violence

Chapter 2 | The Challenge of Promoting Transformational Change

Highlights

The World Bank Group’s support to countries affected by fragility, conflict, and violence for women’s and girls’ economic empowerment and for gender-based violence prevention and response was generally relevant and promoted inclusively owned, deep, sustainable, and scalable approaches.

However, these elements were frequently too weak to produce meaningful and lasting results.

There were trade-offs among these elements—especially among depth, sustainability, and scale—making it difficult for projects to achieve all five elements simultaneously.

There were also trade-offs between project efforts to address short-term emergency needs and efforts to build long-term peace and resilience, although recent projects have improved at this.

Projects had difficulties ensuring that the supply of project-related benefits met the demand for them.

Projects were most relevant when they were based on sound and context-specific gender analyses and addressed gender-discriminatory mechanisms with local and culturally sensitive solutions that recognized the multiple dimensions of discrimination, referred to as “intersectionality,” and not just gender-based discrimination.

In successful cases, projects fostered inclusive ownership through local consultations, decentralized and community-based approaches, and women’s representation in decision-making bodies.

The Bank Group frequently consulted and involved local stakeholders, including women’s organizations, in project implementation, but normally did not in project design, which reduced the relevance, ownership, and sustainability of results.

It was not common for projects to use integrated and multisectoral approaches when attempting to transform gender norms.

Very few project designs included planning to bring activities to scale or make them sustainable.

This chapter discusses the Bank Group’s challenges in supporting FCV-affected countries to achieve transformational change in WGEE and in the prevention of and response to GBV. First, it describes the nature of these challenges. Then it explains how projects have or have not achieved relevance, inclusive ownership, depth, sustainability, and scale and discusses some of the pitfalls the Bank Group has encountered in integrating these elements in the six case study countries. Third, the chapter describes the trade-offs that projects face when pursuing transformational change on WGEE and GBV issues.

The Challenge

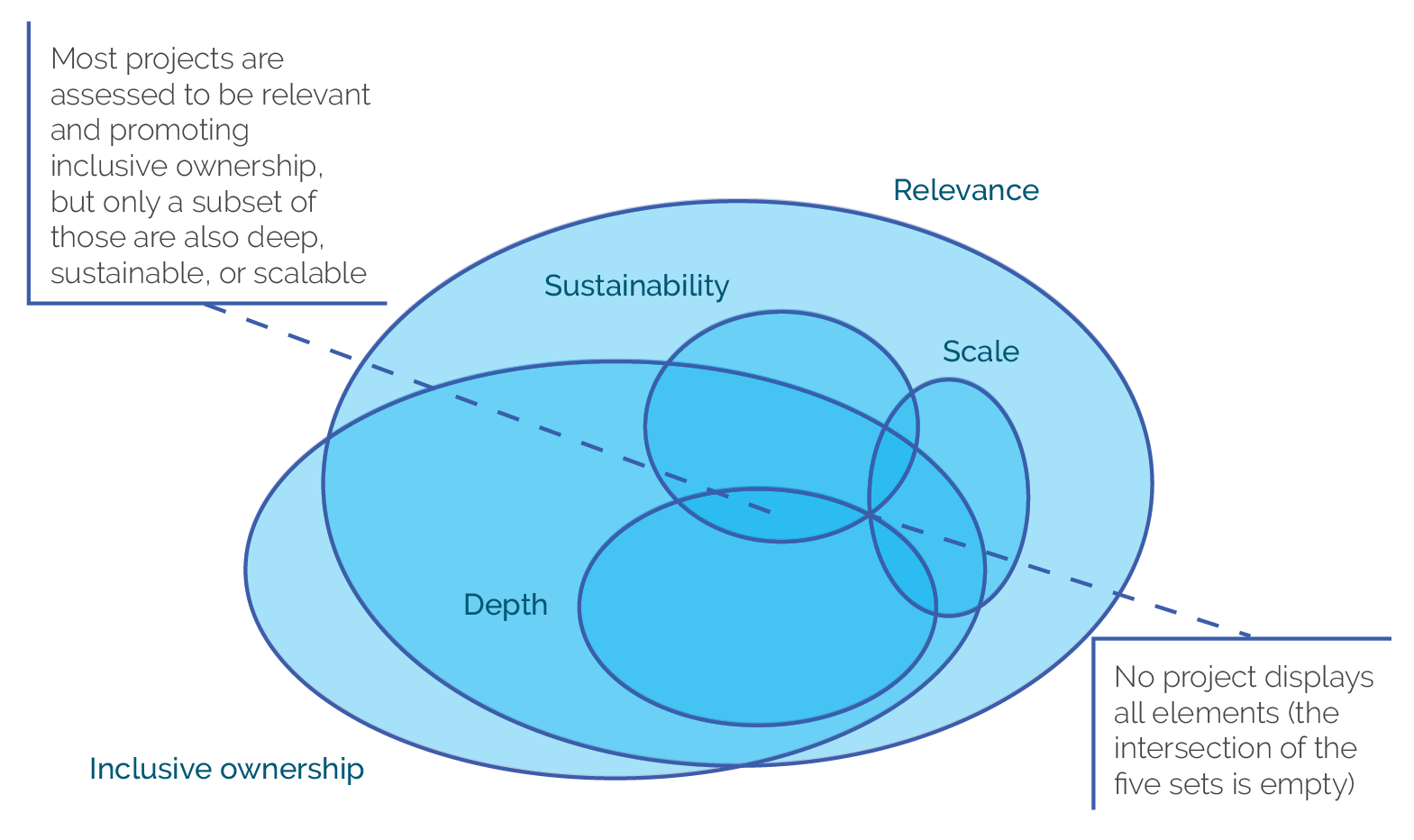

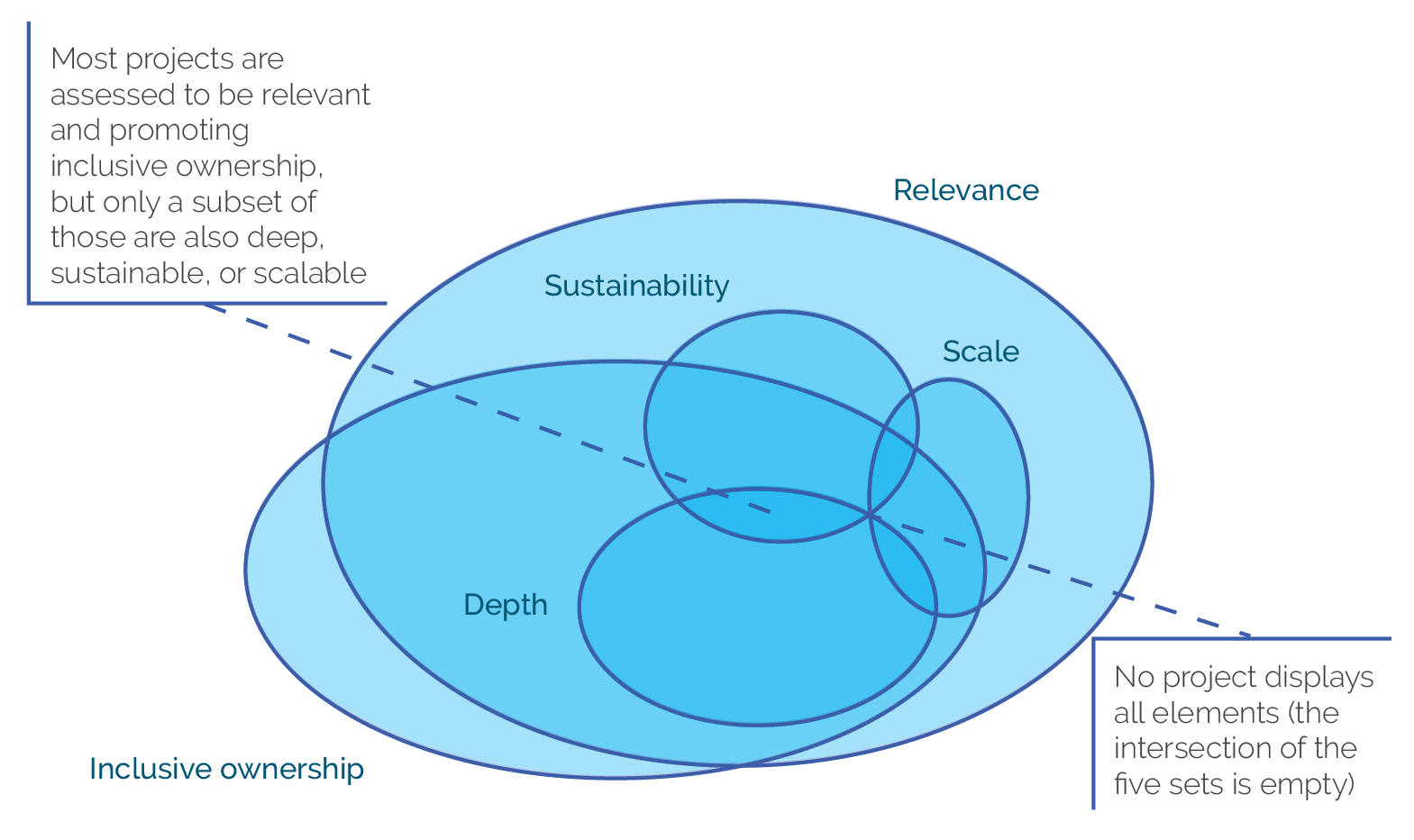

The Bank Group faces challenges in making its support relevant, inclusive, deep, sustainable, and scalable and easing the trade-off among these elements. Bank Group projects that enhance WGEE and address GBV in FCV countries vary in the degree to which they include the individual elements of transformational change—relevance, inclusive ownership, depth, sustainability, or scale—in project designs. Among the 41 project designs that this evaluation analyzed in depth, several were strong in one or more of these elements, particularly relevance and inclusive ownership.1 Depth, sustainability, and scalability were much less prevalent in designs. Crucially, as we will discuss, there are trade-offs among these three elements, and, as a result, the three are rarely found together in the same project design (figure 2.1). These findings have several implications. First, the Bank Group embraced the goal of addressing gender inequalities in FCV countries, as evidenced by its inclusion of elements of transformational change in project designs. Second, there have been challenges in strengthening and expanding each individual element. Third, projects face difficulties in combining the five elements and managing their trade-offs. This raises the question of whether it is possible to resolve these trade-offs within an individual project or whether this problem must be addressed at a higher level. This evaluation offers answers to these questions.

Figure 2.1. Elements Contributing to Transformational Change in Project Design

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The total number of project designs is 41, and the total number of individual projects is 38 (the design of 2 projects was fundamentally changed at restructuring and counted as a new design). Nine projects have no transformational elements that are considered “sufficient” (score 3 or 4) and are outside of every set of the Venn diagram. Project rating criteria are described in detail in appendix A. The number of projects in each set is reported in table A.2, appendix A.

Strengths and Weaknesses in Planning for Transformational Change

The intensity of relevance, inclusive ownership, depth, sustainability, and scale varies from project to project. The evaluation found that these elements were present in projects to varying degrees—not as a yes or no characteristic but on a continuum between yes and no. As a result, the evaluation had to define an absence-presence threshold to make the analysis possible (see appendix A).2 The intensity of each element depends on different project circumstances, such as the operational team’s knowledge and awareness of these elements, the constraints that the project faced, and the opportunities that it could seize.

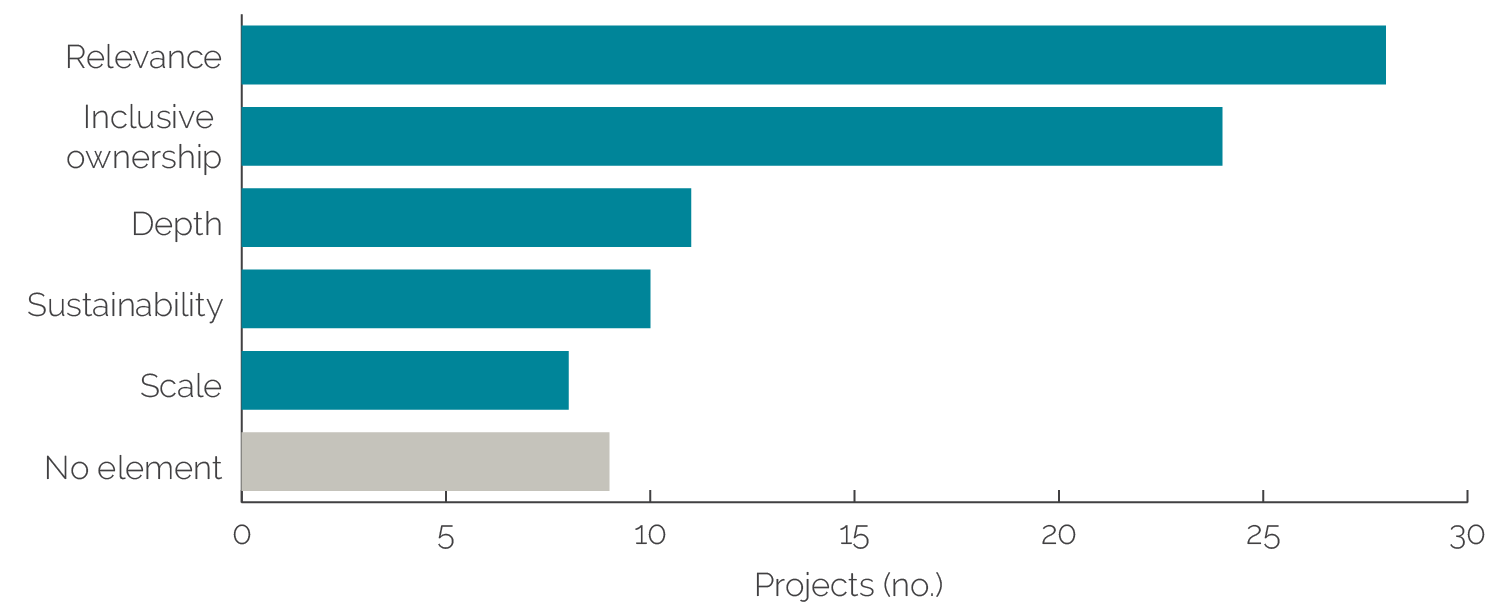

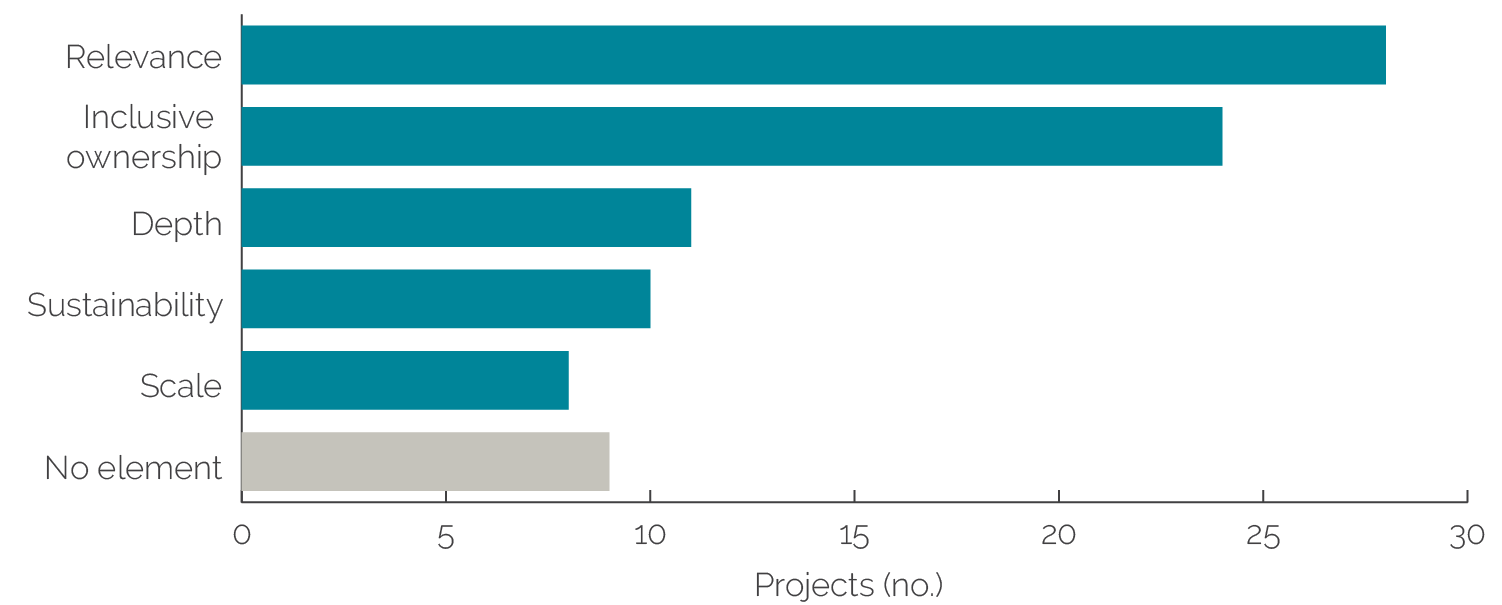

All projects had room to improve the intensity of certain elements. In 9 of 41 project designs, the elements were so weak that their intensity was negligible (figure 2.2). Moreover, even projects that were “sufficiently” relevant, inclusively owned, deep, sustainable, or scalable rarely had individual elements of the highest intensity, let alone all of them at once. Indeed, no single project contained all five elements at an intensity to which the project could be judged “fully transformational.” This is true both of projects that had elements to reduce gender inequalities and of “stand-alone” projects (6 of 41 designs) that focused primarily on reducing them.

Figure 2.2. Prevalence of Individual Elements in Project Design

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Categories are not mutually exclusive. Each element is considered to be present in a project design if it reaches at least a score of 3 on a 0–4 intensity scale (project rating criteria are described in detail in appendix A). The total number of project designs is 41, and the total number of individual projects is 38 (the design of 2 projects was drastically changed at restructuring and counted as a new design).

Relevance

Only two-thirds of the 41 analyzed project designs were relevant (figure 2.2). To be defined as relevant, a project must address GBV or support WGEE in FCV-affected countries and must be tailored to local FCV conditions and demonstrate an understanding of how gender inequalities play out for specific groups of the population under specific contexts. This is recognized as a general principle in the gender strategy: “Although gender equality challenges prevalent in [fragile and conflict-affected situations] are broadly similar to those in other developing countries, important contextual factors call for different operational approaches” (World Bank 2015d, 20). However, almost a third of the project designs were not sufficiently relevant, meaning they were not adequately tailored to the local context and did not adequately address the needs, constraints, and gender inequalities of different groups of women and girls. This finding was surprising because the evaluation team expected all of the selected projects to be sufficiently relevant, based on the selection criteria adopted by the evaluation and applied to projects that explicitly or potentially impact WGEE and GBV.

Several projects used quotas to increase their number of female beneficiaries, but this was only successful when the project also removed obstacles preventing women and girls from benefiting from the project. Quotas did not guarantee that projects included women’s and girls’ views in project designs, met their needs and expectations, or reduced gender inequalities. For example, Chad’s Climate Resilient Agriculture and Productivity Enhancement Project set a 30 percent quota for female beneficiaries, but most activities could not meet it. This was particularly true for the project’s e-services and pilot plots in rural areas, where women had lower access to land, cell phones, internet, and education compared with men. Similarly, in Burkina Faso, 31 percent of the Burkina Faso Agricultural Productivity and Food Security Project’s beneficiaries were women, but for the e-voucher component only 14 percent were women because few women in rural areas have their own cell phones (Sawadogo-Kaboré et al. 2020). In the Solomon Islands, the Community Governance and Grievance Management Project recruited community officers to mediate between chiefs, elders, and local leaders and the provincial and central government, and set a quota of 50 percent female community officers. However, only 2 of the 49 recruited community officers were women. According to the project’s Implementation Completion and Results Report, the main constraints to recruiting women were gender norms, insecurity, and the long distance to travel (World Bank 2022f).

Culturally sensitive projects that recognized and leveraged social institutions successfully alleviated aspects of gender discrimination. For instance, loan officers at Al Majmoua, a Lebanese microfinance institution receiving IFC support through the Blended Finance Facility Middle East and North Africa SME/ Trust Fund for Lebanon, promoted flexible individual loans over group loans, but this had the unintended consequence of excluding women, who worked from home so were less visible to loan officers and who found individual loans too expensive. With the support of IFC, Al Majmoua recruited female loan officers, reduced the collateral requirements for individual loans, reinstituted group loans (making them more flexible), and offered bonuses to loan officers who brought in female clients—all of which increased the project’s number of female beneficiaries. In Chad and Burkina Faso, some projects addressed discrimination that limited women from accessing land by supporting women’s inclusion in traditional land tenure systems, which are common in the rural areas of both countries.3 For example, in Burkina Faso, the SWEDD and the Forest Investment Program (FIP)—Decentralized Forest and Woodland Management Project organized initiatives of advocacy and sensitization on women’s rights to land, involving women and traditional leaders (who are responsible for the distribution of common land), local authorities, and other key stakeholders. These projects supplemented these initiatives with technical and financial support to women’s associations to increase their production and productivity. A woman in Burkina Faso who participated in this initiative reported: “With all this information and the chief here in person, I had the courage to go and ask him for the plot. Thus, I acquired it. I did not know I could do this. Women from another village also obtained a plot to do market gardening.”4 For the SWEDD in Chad, these efforts increased the areas cultivated by women’s groups from 152 to 1,921 hectares between 2016 and 2019 (World Bank 2022g), and the FIP project in Burkina Faso contributed to securing women’s associations’ access to land (World Bank 2023; World Bank Group, DGM Global, and CIF 2020). (See box 4.1 for more details.)

Bank Group projects did not reach the most marginalized women and girls when they failed to recognize women’s and girls’ differential needs and various types of discrimination they faced. Women and girls are not a homogeneous group and face discrimination based not only on gender but also on other identity characteristics, such as age, income, religion, education, ethnicity, disabilities, sexual orientation, marital status, position in the family, forced displacement status, geographical location, and others (Crenshaw 1989; Lutz 2015; Van Eerdewijk et al. 2017; World Bank 2020f). Some projects turned out to be relevant only for some, but not all, vulnerable women because they did not recognize this diversity, referred to as “intersectionality,” and did not provide the specific support that these groups required. Many projects planned to include “women and youth” but neglected the specific needs and double discrimination experienced by women who are also in the youth category. Moreover, women of ethnic minorities can easily be excluded from the project’s beneficiaries. For example, in one province of Burkina Faso, the FIP project gave Peuhl women’s groups grants, but was unable to involve them in local management committees. Illiterate women faced difficulties participating in some projects. For instance, rural women’s illiteracy limited female farmers’ participation in e-support for Chad’s Climate Resilient Agriculture and Productivity Enhancement Project. In some cases, projects provided specific support to address this additional disadvantage. For example, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, an implementing partner nongovernmental organization (NGO) of the Great Lakes Emergency Sexual and GBV and Women’s Health Project (hereafter “Great Lakes Project”) and the GBV Prevention and Response Project included literacy training for project beneficiaries to help illiterate women participate in the activities of village loans and savings associations. Some projects adopted participatory learning techniques to increase the participation of illiterate women. For example, the SWEDD trained the mentors of safe spaces in facilitation techniques. As a young woman explained: “In the space, at the beginning, it was not easy for everyone to speak. But over time, and thanks to the facilitators’ manners, all women participated.”5 Some projects specifically targeted marginalized or vulnerable women: for example, social safety net projects targeted female heads of household; the Democratic Republic of Congo GBV Prevention and Response Project targeted indigenous ethnic groups; and Al Majmoua targeted refugees. These projects, however, failed to tailor their support to each group’s specific needs, even if they explicitly targeted the groups.

Analytical work that adopted an intersectionality lens made project designs more relevant to different categories of women. An assessment of SWEDD-supported safe spaces for young women’s skills development (Population Council 2020) recommended separating participants into two distinct groups—married young women and unmarried adolescent girls—and applying a different curriculum for the two groups to better respond to each group’s needs and expectations. In the Solomon Islands, a study on vulnerable young women’s constraints to economic participation (Woo et al. 2019) informed the Community Access and Urban Services Enhancement Project. There are a few other good examples of analytical products adopting an intersectionality lens. For example, the Chad social safety net diagnostic (World Bank 2016d) analyzed gender-specific vulnerabilities in the different geographical areas, and the Land Property Rights, Farm Investments and Agricultural Productivity in Chad report (Chaherli et al. 2020) examined the impacts of customary and religious law systems on women’s access to land in three macrogeographical areas of Chad (urban areas, the South, and the Sahelian area).

Political sensitivities can undermine the relevance of project designs to FCV contexts, but smart designs can partially overcome this issue. For example, in Burkina Faso, the Financial Inclusion Support Project did not target internally displaced persons (IDPs) because of the government’s objection that supporting IDPs was not a financial inclusion issue but a social inclusion issue, for which social protection mechanisms were better suited. However, project managers still succeeded in indirectly supporting FCV-affected women in two ways. First, the project allowed people risking default because of COVID-19 and other external shocks (including conflict and forced displacement) to restructure their debt. Second, the project supported the governmental institution financing women’s income-generating activities (Fonds d’Appui aux Activités Rémunératrices des Femmes) by allowing digital payments, which facilitated the participation of conflict-affected and forcibly displaced women in the project.6 In Lebanon, the regional Mashreq Gender Facility (MGF) was not able to include Syrian refugees in country-level activities because of the government’s objection, but it established a regional window that facilitated the access of forcibly displaced women to economic opportunities in the three target countries (Hemenway et al. 2022).

IFC had difficulties tailoring its business model to FCV contexts, based on evidence for the six country cases, but was able to successfully invest in a client that targeted FCV-affected populations. IFC has increasingly focused investment and advisory activities on addressing gender inequalities in FCV-affected countries and challenging contexts, but in the countries analyzed there is little evidence that its work is addressing the drivers of gender inequalities related to fragility or the specific needs and constraints of FCV-affected women and girls. Only two of this evaluation’s case studies (Lebanon and the Solomon Islands) had significant gender-relevant IFC investments or advisory services. These activities, however, were not specifically designed to account for gender inequalities in an FCV context—for example, inequalities related to refugees, environmental fragilities, or other contextual factors. One interviewee pointed out that it was difficult to apply IFC’s approach to FCV settings and develop products relevant to FCV conditions. However, IFC showed that it could be done by investing in Lebanon’s Al Majmoua microfinance institution, which specifically targeted female refugee beneficiaries.7 Moreover, the creation of platforms to support peer learning, such as Leaders4Equality (a program that is part of the MGF), is a promising avenue to address gender gaps and cultural norms that limit women’s economic participation in challenging environments.

Gender studies and assessments helped make project designs relevant by tailoring them to local contexts and making them responsive to gender inequalities. Several projects used gender analyses during project preparation to inform their theories of change. For example, the design of phase II of the Regional Sahel Pastoralism Support Project integrated a gender action plan based on a gender assessment conducted during the Mid-Term Review of phase I and a gender gaps study conducted during the preparation of phase II. The gender action plan identified gender gaps among pastoralist populations and proposed measures to address them. In Chad, the Local Development and Adaptation Project (ALBIA) conducted a gender assessment, which included women’s organizations and proposed a list of activities to promote gender equality and women’s empowerment. In Lebanon, the World Bank Group carried out a gender assessment for the Creating Economic Opportunities program, which was canceled, but the assessment still informed the design of MGF. In the Republic of Yemen, the Emergency Electricity Access Project carried out a participatory gender analysis on the target communities’ gender-specific needs for microfinancing opportunities and preferences for solar photovoltaic technology. In some cases, the World Bank used assessments by partners. For instance, the World Bank used a gender assessment by the French Development Agency to inform the design of the Lake Chad Region Recovery and Development Project. The project design followed the gender assessment’s recommendations and promoted women’s participation in community management committees and income-generating activities, psychosocial support to GBV survivors, gender sensitivity trainings for men, and additional gender-sensitive studies to improve support for women’s economic empowerment and their agency.

The Bank Group’s analytical work, however, did not commonly focus on the interplay between gender inequalities and country-specific FCV issues. There is an increasing body of literature showing that FCV affects GBV and WGEE in specific ways,8 but the majority of the analyzed Bank Group knowledge products disregard these interactions. This analytical work seldom examines how FCV exacerbates gender inequalities or is differently experienced by women, men, girls, and boys; nor does it examine how gender inequalities differentially impact FCV-affected groups. Moreover, these knowledge products rarely discuss how gender inequalities exacerbate fragility. A donor in the Republic of Yemen stated that “the World Bank does not distinguish between GBV in emergencies, sexual harassment in the workplace, and gender issues. These are different issues that require different types of interventions, focuses, and strategies.”

Inclusive Ownership

Inclusive ownership was frequent during project implementation but rare during project design. Involvement of local stakeholders is vital in FCV contexts and can improve project ownership at the national, local, and community levels (Atuhaire et al. 2018; Bojicic-Dzelilovic and Martin 2018; UN and World Bank 2018). More than half of the analyzed projects promoted inclusive ownership by consulting with local stakeholders, including women beneficiaries and women’s grassroots organizations, and involving women in decision-making bodies and decentralized and community-based development approaches. The evaluation, however, unveiled that the Bank Group often gathered the input of local stakeholders but rarely integrated that input into project designs, which undermines the long-term ownership over the project by these stakeholders and can decrease project relevance and efficacy. The Bank Group more commonly involved women’s community-based organizations and local NGOs in the implementation of subprojects whose designs were already finalized by the government’s implementing agency. This was the case for the SWEDD project, the Emergency Food and Livestock Crisis Response Project in Chad, and the GBV Prevention and Response Project in the Democratic Republic of Congo. These findings echo the Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) evaluation Engaging Citizens for Better Development Results, which found that the Bank Group is not using citizen feedback to inform project designs or trigger course corrections during implementation (World Bank 2018g).

The World Bank operating modalities can restrict the extent of inclusive ownership. The evaluation found that the Bank Group’s business model, which uses the central government as its main interlocutor and counterpart in country programs, limits the Bank Group’s capacity to achieve local inclusive ownership over projects. As one informant put it: “In FCV situations, the key is to work the local way. We did a portfolio review and found that the World Bank has been struggling with impacting final beneficiaries in the countries because projects were focused on central level reforms and administration, but had problems with producing impact on the ground.” Informants from women’s rights organizations and CSOs believe that the World Bank can be more impactful in addressing gender inequalities by strengthening its partnership with CSOs that have experience working with communities and know how to effectively support them. A key informant of a local CSO in Burkina Faso said: “The [World] Bank would benefit from working with well-organized civil society structures. Even the government realizes that it cannot move forward without civil society. Where the government does not arrive, we do. We can better transform things. But directly with civil society, we know the field well.”9 IEG’s Social Contracts and World Bank Country Engagements: Lessons from Emerging Practices meso-evaluation documented a similar phenomenon and noted that the World Bank’s operating logic did not facilitate social contract thinking, as citizens and other social actors (including subnational authorities, which play a key role in service delivery) were unlikely to be involved in Bank Group activities (World Bank 2019c).

In the Republic of Yemen, the Bank Group adopted a decentralized and multistakeholder approach because a central government counterpart was absent, but it missed an opportunity to involve the local stakeholders most engaged on gender issues. As IEG’s World Bank Engagement in Situations of Conflict: An Evaluation of FY10–20 Experience (World Bank 2021e) highlights, in situations of open conflict, United Nations (UN) agencies are better equipped than the World Bank to mediate and negotiate with multiple stakeholders. Following the suspension of disbursements to the Republic of Yemen under Operational Policy 7.30, the UN began to implement the Bank Group’s projects there. In so doing, the UN operated through community-, district-, and governorate-level stakeholders, including local implementing agencies and, when possible, relevant government bodies. For example, the Emergency Crisis Response Project adopted a community-based approach to identify, implement, and maintain small community infrastructure subprojects through labor-intensive public works. The UN involved women, youth, and IDPs in consultations and decision-making processes at the community level. This approach helped strengthen social cohesion, ownership, and engagement, as women helped identify project priorities and design activities that responded to their needs. However, in the Republic of Yemen, the World Bank did not collaborate with the stakeholders most engaged on gender issues, which partly explains why its contribution to WGEE and to GBV prevention and response was very limited.

Depth

Few projects of those analyzed adopted integrated, holistic approaches to address the root causes of gender inequalities. The root causes of gender inequalities are complex and require “deep” approaches that are integrated and comprehensive. However, figure 2.2 shows that projects designed to achieve deep change were not very frequent. Those that did include deep designs were almost all recently designed projects: only phase I of the SWEDD and the Democratic Republic of Congo Great Lakes Project were deep projects designed before 2019. The SWEDD, for example, uses a multisector strategy and multiple entry points to increase women’s and girls’ empowerment and access to quality reproductive, child, and maternal health services. On the supply side, the project improves the quality of reproductive health services, whereas on the demand side, it builds girls’ and women’s capacity to make decisions, including on their fertility, and use reproductive health services. The project also intends to change gender norms through media and community-based communication activities and by actively engaging men, boys, and political, religious, and traditional leaders to work toward eliminating GBV.

Projects that did not adopt a theory of change that included all the necessary conditions for WGEE were less effective in promoting WGEE. The theories of change for projects that effectively support WGEE can be very complex (as shown in figure 1.1). These theories of change must consider multiple context-specific constraints to create the necessary conditions for WGEE, such as male acceptance or women’s freedom of movement, and women’s access to time, lands, skills, inputs, credit, markets, and information. For projects in which these various elements were not analyzed or integrated into the project’s design or implementation, intended results were not fully achieved at closing. For instance, the FIP—Decentralized Forest and Woodland Management Project in Burkina Faso technically and financially supported women’s income-generating activities; however, it underestimated the gaps in women’s technical capacity and ability to access markets, transportation, and business inputs, such as water and other resources. Focus group discussions revealed that failing to account for these gaps undermined the profitability and sustainability of project activities. Likewise, the SWEDD project provided young women with electrical and plumbing installation kits and technical and business development training to facilitate their access to traditionally male activities and increase their economic empowerment. However, when consulted for this evaluation, none of the beneficiaries had started their own business. This was because the project support neglected some elements of the theory of change: girls could not access credit for start-up costs, the installation kit did not include all the necessary materials or equipment for starting a business, and the training did not cover all the aspects required for a start-up firm. As a result, instead of starting their own businesses, the young female beneficiaries worked as apprentices in a male-headed firm.

To produce deep change in GBV and WGEE, it is necessary to consider the interrelationships between the two. The theory of change used by this evaluation (chapter 1 and appendix C) draws from an increasing body of evidence that shows the important interrelationships between GBV and WGEE. WGEE can enhance women’s status, agency, and bargaining power, thus decreasing GBV (Désilets et al. 2019; Kiplesund and Morton 2014; Klugman et al. 2014). However, it may also increase intimate partner or domestic violence (Désilets et al. 2019; IASC 2015; ICRW 2020; IRC 2019; Kiplesund and Morton 2014; Klugman et al. 2014) as men may feel uncomfortable or resentful about these advances for women. As such, these efforts require engaging men and boys to change gender norms, create a conducive environment for change, and build safe and equal relationships between men and women. They also require FCV settings to improve safety and protection from GBV as a precondition for women’s and girls’ equitable participation in economic life and decision-making (IRC 2019; Sida 2009).

The World Bank Group mitigated the risk of WGEE-related projects causing GBV as an unintended outcome by considering the interlinkages between WGEE and GBV in project designs. The Great Lakes Project, for instance, promoted GBV survivors’ economic empowerment to support their socioeconomic integration but also to reduce their vulnerability to violence and the consequent risk of GBV. The follow-on GBV Prevention and Response Project reinforced this component in design. The SWEDD project supported adolescent girls’ and young women’s economic empowerment to prevent child marriage and other forms of GBV, including domestic violence. As a young woman explained in a focus group, “When you stop holding out your hand every time, your husband respects you and sometimes negotiates.”10 The implementing NGOs also ensured that community leaders asked for the approval of husbands and fathers for the girls to participate in project activities;11 organized activities of sensitization through radio, in-person training, and other channels; and targeted different community groups to foster men’s support and reduce the risk of male resistance and domestic violence. In Burkina Faso, the Social Safety Net Project, informed by a local study that had been conducted in collaboration with the Africa Gender Innovation Lab (Gnoumou Thiombiano 2015), transferred cash to all the wives of vulnerable polygamous households to mitigate the risk of intrahousehold conflict and domestic violence. The Lake Chad Region Recovery and Development Project plans to engage and sensitize men “to ensure the broader understanding and encouragement of women’s participation in these activities [labor-intensive public works], so as not to create conflicts at the household level” (World Bank 2020e, 26). The Community Access and Urban Services Enhancement Project in the Solomon Islands, by contrast, did not consider the potential unintended negative effect that promoting WGEE could generate and ran into strong male resistance. Some husbands were upset when their wives participated in labor-intensive public works trainings because they felt threatened by their wives’ education and by that class being coeducational. Some husbands went so far as to burn their wives’ Community Access and Urban Services Enhancement Project training certificates.

Analytical work that investigates the links between WGEE and GBV supports deeper project designs, but this is very infrequent. Only 12 of 60 analyzed knowledge products explore the relationship between some aspect of WGEE and GBV. These are all gender-focused reports. Four are gender assessments, some of them recent (Lebanon: World Bank and UN Women 2021; Chad: World Bank 2020a), with in-depth analysis on, for example, how GBV drives gender inequalities in health and justice services and impacts women’s productivity and access to the labor market (Lebanon: World Bank and UN Women 2021) or how GBV becomes a barrier to women’s full participation in social and economic life (Democratic Republic of Congo: World Bank 2017b). Most of the remaining reports are private sector analyses of women’s participation in value chains or leadership positions. These include IFC knowledge products that discuss GBV’s negative impact on WGEE—for example, GBV’s impact on absenteeism, worker turnover, low productivity, and occupational hazards (IFC 2016, 2019b). IFC’s SolTuna report for the Solomon Islands (IFC 2016) discusses the concrete actions that the SolTuna company has taken to address sexual harassment in the workplace. These examples aside, the fact that so many knowledge products—especially sectoral or strategic diagnostic products—ignore these interlinkages greatly limits the Bank Group’s ability to develop deeper, more comprehensive interventions.

Sustainability

Sustainability is rarely planned for in project designs.12 Aside from scale, sustainability was the most difficult element of transformational change for projects to pursue; only 10 of the 41 analyzed project designs sufficiently incorporated sustainability in their designs (figure 2.2). One of the reasons is that achieving sustainability and scale requires stability, strong institutions, and strong financial capacity of national and subnational governments, which are rare in FCV situations.

Projects aimed for sustainability by building on existing processes and actors and, less frequently, by improving the enabling environment. Some projects pursued sustainability by building on earlier phases of the same projects and supporting preexisting processes and engaged actors. For example, the FIP—Decentralized Forest and Woodland Management Project developed the capacity of communities and local institutions, such as women’s and farmers’ grassroots organizations, to sustainably manage forests and foster women’s voice, agency, and economic empowerment. Very few projects pursued sustainability by changing the enabling environment for WGEE and for GBV prevention and response—that is, by improving the country’s policies, legal framework, and formal and informal institutions. The SWEDD, however, did this in several ways: first, by engaging with traditional and religious leaders to change gender norms and with political leaders to adopt national policies for gender equality; second, by improving health systems and women’s and girls’ sexual and reproductive health; third, by helping countries in the Sahel produce and disseminate analytical work; and fourth, by building the capacity of government experts to plan and monitor programs that harness the demographic dividend.13 The SWEDD’s new phase has increased the project’s focus on the enabling environment, particularly on strengthening the country’s legal framework and adopting budget practices that integrate the demographic dividend.

Scale

Few projects were designed to produce large-scale changes in WGEE and GBV prevention and response. There are three ways for projects to achieve scale:14 first, by progressively covering more people across more geographic areas; second, by strengthening country systems, including institutions and policy frameworks, to expand to a larger scale (this is also called endogenous scaling up and is intrinsically more sustainable); and third, by partnering or coordinating with other donors to develop a common strategy to deliver larger, complementary programs or “delivering as one.”15 Only 8 of the 41 analyzed project designs planned for larger scales. Four projects in the Republic of Yemen and the Solomon Islands were designed to achieve scale in the first way, by progressively targeting more and more beneficiaries with cash transfer or cash for work programs for vulnerable women. Another four projects planned for scale in the second, more sustainable way by strengthening national or subnational systems. This was the case for the FIP—Decentralized Forest and Woodland Management Project design, which integrated a gender-sensitive angle into the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation country strategy.16 Other examples of the second way were the Social Safety Net Projects in the Sahel, which aimed to consolidate national social safety net programs and strengthen institutions. These Social Safety Net Projects were also the only ones that followed, to some extent, the third way of scaling up by developing synergies with other international development partners to establish a unified registry, at the country level, of the beneficiaries of social protection programs.

The Trade-Offs

The Bank Group faced trade-offs among the five elements of transformational change. This evaluation has identified three such trade-offs. The first trade-off is among scale, depth, and sustainability (figure 2.1). The second type of trade-off is among the different parts of the project theory of change and emerges when projects attempt to achieve deep change. The third is the nexus between emergency humanitarian and development goals, which is often a temporal trade-off between the short- and long-term perspectives in FCV situations.

Trade-Offs among Scale, Depth, and Sustainability

There are key trade-offs among scale, depth, and sustainability. The evaluation observed only one project design that aimed to achieve both scale and deep change (figure 2.1) and found no examples where all three were achieved at once. The MGF planned for both scale and depth. The MGF was a technical assistance to improve the enabling environment for WGEE in three Mashreq countries (including Lebanon). The MGF was at scale, as it worked simultaneously at the subnational, national, and regional levels, and at depth, as it supported different types of activities including capacity building, evidence generation, and experience exchanges. Even so, the MGF still struggled with sustainability. Several MGF results were potentially sustainable, such as the passage of a sexual harassment law and the development of women’s economic empowerment action plans in five ministries,17 because these strengthened the enabling environment. However, the MGF was not connected to other relevant projects and partners to consolidate its achievements and new engagements; thus, the facility as such was not sustainable. No other analyzed project planned for both scale and depth. For example, the Sahel’s Adaptive Social Protection projects planned for scale by supporting national social safety net systems that targeted FCV-affected populations and vulnerable women, including female heads of households, lactating women, and pregnant women. However, the depth of the project designs was limited because they did not try to transform gender roles and relations. Moreover, these projects, like other social safety net projects, defined eligibility criteria at the household level, thereby ignoring intrahousehold gender dynamics and inequalities.18

There are trade-offs among scale, depth, and sustainability for both WGEE and GBV projects. National social safety net projects, which are large-scale, have been successful in increasing the resilience and economic empowerment of vulnerable women. However, these projects only produced deep and sustainable results at the local level, where they supported small-scale activities for beneficiaries’ productive inclusion, or “graduation,” into income-generating activities. These activities were not a part of the national system of social safety nets. Likewise, the SWEDD, despite its phase II strategy to scale up by improving the enabling environment, struggled to provide coverage to all of the countries’ in-need women and girls. Many of these trade-offs emerge from resource constraints. Scaling up a bundle of interconnected interventions to achieve deep change requires large financial resources that are difficult to mobilize in FCV countries. As a key informant reported: “The dormitories (for girls living far from the secondary school) are currently overwhelmed. There are plenty of girls on the waiting list. Resources are the challenge for scaling up. It is an exorbitant cost. In the country, there are one million girls at risk of child marriage, but we cannot support more than 600 girls. The expertise is there, the political will is there, the communities are welcoming, now it is a matter of resource mobilization. The World Bank alone cannot meet these needs.”

Various integrated projects achieved results in GBV prevention and response, but they remained small-scale and were not yet sustainable. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the African Great Lakes Project supported GBV survivors through complementary and coordinated interventions, but the scale of the combined intervention was small, and the intervention was not sustainable.19 The follow-on GBV Prevention and Response Project in the Democratic Republic of Congo intends to expand the coverage of the Great Lakes Project,20 but it cannot increase the full package of services to GBV survivors.21 Equally, the SWEDD in Burkina Faso and Chad helped reduce the incidence of child marriage and other forms of GBV by promoting girls’ education and skills development,22 but these activities were small-scale and not financially sustainable. IFC engaged with 15 of the largest companies in the Solomon Islands, all of which committed to improving gender equality by promoting respectful and supportive workplaces for nearly 7,000 employees,23 42 percent of whom were women. However, this two-year initiative was too short to ensure deep and sustainable results, and it did not purposefully engage with the government and other projects to consolidate its achievements.

Trade-Offs among the Different Parts of the Theory of Change

The second type of trade-off is among the different parts of the theory of change that are necessary for effectively supporting WGEE and preventing and responding to GBV. Addressing GBV and promoting WGEE requires holistic and integrated approaches, involving multiple sectors, that cover all the elements of the theory of change. This evaluation found that projects that, for example, were unable to balance supply and demand undermined their effectiveness. In some cases, projects created high expectations that generated a strong demand that the project could not meet. For example, the SWEDD adopted a multipronged approach that, on the demand side, aimed to remove constraints to women’s and girls’ access to services (through skills development, incentives for girls’ education, communication campaigns, and engagement of opinion leaders, men, and boys as key agents) and, on the supply side, intended to improve the quality of education and reproductive health services. However, the project was unable to ensure the supply of education and reproductive health services matched the increase in demand.24 It also happened that the services directly provided by the SWEDD—for example, safe spaces for young women’s and adolescent girls’ skills development—were in short supply with respect to the demand. As a mentor reported: “There was a census by the local association in collaboration with the village’s community development committee. Afterward, the project team came to make the final selection of the girls and women beneficiaries by lottery. The women and girls who wanted to participate were numerous: the number exceeded the capacities of the project. The need is great. We would like the safe spaces to continue to be able to reach everyone in the village.” On the other side, the Great Lakes Project in the Democratic Republic of Congo did not adequately address demand-side constraints, such as the long travel distance to services and the fear of stigmatization and social exclusion, hindering GBV survivors’ access to GBV case management. As a result, the number of GBV survivors who asked for health support was lower than expected.25

Trade-Offs between Humanitarian and Development Efforts

The third trade-off is between addressing humanitarian needs and pursuing longer-term development goals. Many key informants, both inside and outside the Bank Group, stressed the need to pursue long-term goals in FCV contexts, notably by building the resilience of FCV-affected populations and supporting FCV countries to exit from crises. According to the Bank Group’s FCV strategy, this is referred to as working “across the humanitarian-development-peace nexus” (World Bank Group 2020, 59). At the same time, the informants recognized the difficulty in investing in long-term goals, such as strengthening resilience, peace, and gender equality, when investments are needed for emergencies.26 One may question, for example, whether it is possible to aim for long-term goals within countries, such as the Republic of Yemen, where there are much more urgent matters of violence, famine, disease, displacement, and so on. To overcome this trade-off, the Lessons Learned Study: Yemen Emergency Crisis Project (ECRP) proposes adopting a pragmatic approach that is clear on how the country’s transformation will occur and incorporates both the longer-term and shorter-term views (UNDP 2019). The study suggests that the activities should be articulated along a continuum of expected activities and results, ranging from short-term coping measures that provide temporary relief for the urgent needs of individuals, households, and institutions to more systemic interventions that generate deeper and more sustainable results.

The World Bank Group bridged the humanitarian-development-peace nexus when it strategically collaborated with humanitarian actors. The World Bank’s comparative advantage lies in providing longer-term development solutions, not in short-term humanitarian relief. For this reason, the adoption of a nexus approach that meets both emergency and development needs requires the Bank Group to develop strong and strategic collaborations with humanitarian actors. In the Republic of Yemen, for example, the Bank Group established partnerships with UN agencies that have experience working in humanitarian settings. In this country, therefore, the Bank Group can focus on its comparative advantage in delivering basic services, building institutional capacity, and enhancing resilience among populations. Doing so also allows the Bank Group to focus on gender-related development issues in the Republic of Yemen, which it is beginning to do. This aspect is highlighted in the Bank Group’s Country Engagement Note (FY22–23) for the Republic of Yemen, which commits to supporting women’s and girls’ empowerment and building women’s resilience, because “despite many challenges, women in [the Republic of] Yemen are demonstrating resiliency and innovation in the face of crises” (World Bank 2022c, 21).

- Each element was rated on a scale of 0 to 4 and was considered present in project design if the intensity was 3 or 4 or absent if it was 0 to 2.

- The evaluator assessed to what extent each project planned (at design) the different elements of transformational change (relevance, inclusive ownership, depth, sustainability, and scale). To this end, each evaluator rated the five elements of transformational change on a scale of 0 to 4. Each rating was accompanied by a justification. The assessment of each element of transformational change was guided by specific questions to ensure harmonization of the rating criteria across evaluators. All the ratings were reviewed at the end by a second evaluator to ensure alignment. A threshold of 3 was chosen to define the presence (3 and 4) or absence (0 to 2) of each factor. A “relevant” project, therefore, has to be understood as a “relevant enough” project—that is, where relevance is above the threshold. The same goes for the other elements.

- In Burkina Faso, the prevalent land tenure system in rural areas is the customary system. According to the customary laws, the traditional leader (chef de terre) distributes the land to men, whereas women receive plots from their husbands or other male members of their household (Gender and Land Rights Database, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, access date: January 2022, https://www.fao.org/gender-landrights-database/en/). In Chad, several customary land tenure systems coexist, but they have some elements in common. Traditionally, land is considered the collective heritage of a community, and it is sacred and inalienable. In the north and south of the country, the perception of the land as a community asset remains very strong. Land is managed within the framework of patrilineal organizations structured around traditional authorities (Chaherli et al. 2020).

- In French: « Avec toutes ces informations reçues et la disposition du chef du village devant tout le monde, j’ai eu le courage d’aller demander la parcelle à ce chef. J’ai utilisé mes relations en passant par le fils du chef qui était un ami à mon mari. . . . Ainsi, j’ai acquis ma parcelle sur laquelle je cultive. . . . Avant cette rencontre moi je ne savais pas que je pouvais demander une parcelle à un chef de terre et que ce dernier pouvait me l’octroyer. Je l’ai appris dans cette expérience. D’autres femmes aussi ont obtenu des parcelles c’est le cas des femmes de Bourasso qui ont pu gagner une parcelle pour faire le maraichage. »

- In French: « Dans l’espace, au départ, ce n’était pas facile de prendre la parole pour tout le monde. Mais avec le temps et la façon de faire des animatrices, toutes les femmes participaient. »

- The project did not allow the fund to access the project’s guarantee schemes, which resulted in excluding informal female entrepreneurs (the overwhelming majority of female Independent Evaluation Group World Bank Group 37 entrepreneurs in Burkina Faso) from credit, which was partially compensated by introducing digital payments. This decision was driven by the initial choice of the Global Practice to focus only on the formal sector.

- At some point, however, Al Majmoua stopped including refugees after a request from the government.

- Conflict and fragility (i) increase violence against women and girls before, during, and after conflict and negatively impact service delivery and women’s and children’s human development (Buvinic et al. 2013; Kelly et al. 2021; Pereznieto, Magee, and Fyles 2017); (ii) increase women’s vulnerability to poverty, especially women heads of households and widows in humanitarian settings (Buvinic et al. 2013; Klugman 2022), and (iii) amplify gender inequalities in accessing assets, productive resources, and jobs (Klugman 2022; OECD 2020).

- In French: « La Banque gagnerait à travailler avec les structures bien organisées de la société civile. . . . L’état lui-même se rend compte que l’état ne peut pas avancer sans la société civile. Là où l’état n’arrive pas, nous pouvons arriver. . . . Nous pouvons mieux capter, mieux transformer les choses. Mais directement avec la société civile, nous connaissons bien le terrain. »

- In French: « Quand tu ne tends plus la main chaque fois, le monsieur te respecte et négocie parfois. »

- A young woman participating in a focus group stressed that involving participants’ husbands and fathers and explaining to them the type of activities organized in the safe spaces was important to get their support: “There was no problem with participation because before starting, we involved our husbands to avoid any problem. . . . Our husbands and dads were called to ask their opinion on the participation of their wives and daughters in the safe space. . . . Then, the project brought us together with our husbands and fathers of daughters to check everyone’s support: everyone agreed before we started. When we came back from the talk, our husbands were curious to know what subjects we talked about and we let them know.” (In French: « Il n’y a pas eu de problème de participation car avant de commencer on a impliqué nos maris pour éviter tout problème. . . . Nos maris et nos papas ont été ont appelés pour demander leur avis sur la participation de leurs épouses et leurs filles à l’espace sûr. . . . Ensuite, le projet nous a réuni avec nos maris et papas des filles pour vérifier l’adhésion de tous : tous ont marqué leur accord avant que l’on ne commence. . . . Lorsque nous revenons de la causerie, nos maris sont curieux de savoir de quels sujets on a parlé et on leur raconte. »)

- In the context of this evaluation, sustainability was not understood as the ability to secure additional development aid for a subsequent phase of the project. Sustainability was defined 38 Addressing Gender Inequalities in Countries Affected by Fragility, Conflict, and Violence Chapter 2 as the sustainability of the changes produced at the level of beneficiaries (for example, by strengthening women’s resilience) and sustainability of country and local systems to acquire and maintain their ability to continue to produce this change in the future (for example, via changes in formal and informal institutions to better address GBV and support WGEE). Improving the enabling environment by making institutions (state, religious, and customary laws and institutions; public service delivery systems; markets; and so on) work for the beneficiaries is addressing, at its core, the issues of the sustainability and continuity of the intervention to achieve and maintain outcomes in the medium and long term.

- For example, government experts were trained in developing the National Demographic Dividend Observatory and using it for decision-making, development planning, and monitoring progress to harness the demographic dividend. The demographic dividend is the economic growth potential that can result from shifts in a population’s age structure, mainly when the share of the working-age population (15 to 64) is larger than the non-working-age share of the population (14 and younger, and 65 and older). (Source: https://www.unfpa.org/demographic-dividend#0, accessed June 2023.)

- Increasing the number of beneficiaries through additional financing or a second or third phase of the project is not considered “scaling up” if the project still remains small-scale with respect to country needs or does not support a strategy of endogenous scale-up or coordination.

- IFC’s Respectful Workplaces Program, which started as a component of the Pacific WINvest project, has now become a global offering that is being deployed with clients in Fiji, Kenya, Myanmar, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam and will further expand to South Africa and the English-speaking Caribbean region. This evaluation has not assessed this specific strategy of scale-up at the global level.

- This objective—not yet achieved—is going to be integrated into the new Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation support project, currently under preparation (source: interviews with key informants).

- The sustainability of these results will critically depend on the implementation plan of the new law and the action plans.

- The gender assessment of the Sahel Adaptive Social Protection Program confirms the findings of this evaluation (Pereznieto and Holmes 2020). In Burkina Faso, cash transfers were delivered to all wives in polygamous households who were pregnant or mothers of children younger than five years of age to prevent women’s discrimination and domestic violence. The impact of this criterion of targeting has not been evaluated yet.

- The number of survivors of GBV supported by the Great Lakes Project in the Democratic Republic of Congo was 17,741 in five years. The World Bank considered this coverage as “large scale” (World Bank 2020h, 47). However, this was the total number of GBV survivors receiving at least one of the four services provided, whereas the scale of the combined intervention was much smaller. The number of women benefiting from mental health support was only 1,064, and 49 percent of GBV survivors received only one service.

- The result indicator of the new GBV project in the Democratic Republic of Congo is 60,000 GBV reported cases who access at least one service supported by the project.

- Various reasons explain why beneficiaries cannot receive all services: the project’s financial resources are limited, coordination among the implementing partners is weak, the public health service providers’ ownership of the project is low (as reported by the Mid-Term Review), and the local referral system is weak. To scale up, the project would need a robust long-term strategy to implement partners’ ownership and coordination (including with civil society organizations and public health services) and to define how to expand the holistic GBV case management.

- Data from impact evaluation are not available yet. These findings are based on interviews and focus groups with key informants (including female beneficiaries) and review of monitoring and evaluation reports.

- They represent about 1.8 percent of the current labor force of the Solomon Islands, which amounts to 360,730 according to estimates in 2021 (https://data.worldbank.org).

- In the second phase, the SWEDD aims to address this gap by establishing synergies with other sector projects to increase public investments in reproductive health and girls’ education.

- The expected number was 20,075, whereas the number achieved at the end of the project was 14,446 (World Bank 2020h, 59).

- For example, a key informant from a local women’s organization that supports women of returnee communities in Chad reported: “[These women] have many problems. . . . They do not have food; they do not have land to farm; their children do not go to school. They do not know what to do; they have livelihood problems.” (In French: « Elles ne reçoivent pas les vivres, elles n’ont pas la terre pour cultiver, les enfants ne partent pas à l’école. Elles ne savent pas quoi faire. Elles ont des problème de moyens d’existence. »)