International Finance Corporation Additionality in Middle-Income Countries

Chapter 4 | Factors of Success and Failure

Highlights

For the International Finance Corporation (IFC) to realize additionality, a chain of events must take place, including identifying anticipated additionality, deploying tools or support to transform anticipated additionality into realized additionality, and assessing and addressing whether the anticipated additionality is being realized or not. Internal and external factors influence these events, both at the project level and at the country and sector level.

Project-level internal factors include IFC’s work quality, staff capabilities, and internal procedures. Work quality is the leading internal factor. Work quality during monitoring and supervision is especially important for nonfinancial additionality because it tends to be realized over the life of a project rather than at disbursement.

Staff capabilities (expertise, experience, and local presence) are the next most important internal factor, followed by IFC procedures and incentives (including safeguards, quality reviews, and systems for tracking additionality).

Project-level external factors include client capacity and commitment, the political and policy environment, and competition and collaboration with other financiers. Given that many (especially nonfinancial) additionalities are based on clients changing their behavior (for example, adopting new practices and standards), clients’ willingness and capability to follow through are key. Realization of additionality is higher for repeat clients, especially in lower-middle-income countries. A supportive policy, regulatory, and political environment is vital for IFC to realize additionality, whereas unfavorable policies toward private sector solutions can sharply impede its realization. Finally, the presence of other financiers creates fertile ground for collaboration but may also induce competition where the flow of bankable deals is limited, or private finance is abundant.

Through a learning lens at the country and sector level, we observe several factors influencing realization of additionality beyond the project level, including IFC’s long-term presence and engagement—strategic planning for country sectoral engagement, collaboration with the World Bank and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency, and the range of external factors described.

There is great value in learning what enables IFC to realize additionality and what prevents it from doing so. By identifying success and failure factors, IFC can realize more additionality more often. IEG finds further learning value in considering factors that may work beyond the project level to influence IFC’s success in realizing additionality.

For IFC to realize additionality successfully, a chain of events must align. First, it must correctly identify the additionality its support will realize. Second, it must work toward transforming anticipated additionality into realized additionality. Doing so requires deploying the right tools or support. Finally, IFC must generate and use information about whether the anticipated additionality is being realized to supervise its projects and, in cases where anticipated additionality is not being realized, to take corrective action.

However, whether realization happens involves many factors, both internal (within IFC’s control) and external (beyond it). Both internal and external factors can facilitate the steps required to realize additionality (if they are present) or frustrate them (if they are deficient). This chapter first presents evidence and findings on the factors internal to IFC that it can most directly control. Second, it presents evidence on factors external to IFC that it can seek to anticipate, mitigate, or influence. Understanding these factors helps explain both cases in which IFC realized additionality and cases in which it did not. A final section considers factors that may exist beyond the project level but have a direct bearing on project success in realizing additionality.

Project-Level Internal Factors

Several internal factors within IFC’s control affect the realization of additionality. They include IFC’s work quality, staff capabilities, and internal procedures.

Work Quality

IFC’s work quality is the leading internal factor influencing the realization of anticipated additionalities, both positively and negatively. Because work quality and the realization of additionality are rated, we can observe the relationship between the two. IFC and IEG evaluate the quality of IFC’s work at two stages: (i) project screening and appraisal and (ii) project monitoring and supervision. Controlling for various potential explanatory characteristics and factors, IEG’s econometric analysis of evaluated projects shows that IFC work quality bears a significant positive relationship with the realization of both financial and nonfinancial additionality, but the magnitude of the influence is stronger for nonfinancial additionality. A project with good overall work quality is 17 percent more likely to realize financial additionality. However, when controlling for multiple possible explanatory factors, it is 31 percent more likely to realize nonfinancial additionality (table 4.1).

Table 4.1. Average Marginal Effect of Work Quality on Successful Realization of Additionality (percent)

|

Aspect |

Financial Additionality |

Nonfinancial Additionality |

|

Overall work quality |

16.8 |

31.1 |

|

Screening and appraisal |

11.4 |

20.6 |

|

Monitoring and supervision |

7.8 |

16.3 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group econometric analysis of evaluated International Finance Corporation investment projects.

Note: Relationships statistically significant above a 95 percent confidence level are indicated. The analysis controls for project tier, country income category, region, International Finance Corporation industry group, client and project characteristics, time period, and ratings of country political stability, government effectiveness, control of corruption, and domestic private sector credit depth.

Both at project initiation and over the life of the project, work quality has a larger marginal effect on IFC’s realization of nonfinancial additionality. Good work quality at project initiation (screening and appraisal) increases the chance of realizing financial additionality by 11 percent and the likelihood of realizing nonfinancial additionality by 21 percent. Good work quality over the life of the project (monitoring and supervision) has a limited, significant benefit for financial additionality (an 8 percent higher likelihood of realization) but a larger benefit for nonfinancial additionality (a 16 percent higher likelihood of realization).

At screening and appraisal, additionality (in particular, financial additionality) is not always well identified. One important type of error at appraisal is when initial claims of additionality prove factually incorrect. Such claims can happen when IFC erroneously claims that a feature of its support is substantially superior to what is available in the market or other sources. For example, in the case of an Albanian property development company, the evaluation found that local banks were providing competitively priced funding for up to 10-year tenors; therefore, IFC’s financing was incorrectly claimed as additional. In IEG’s portfolio review of evaluated projects, the anticipated additionality statement was not correct in 40 percent of project claims where financing structuring additionality was not realized. Regarding noncommercial risk mitigation, 23 percent of the unrealized claims were found at evaluation to be incorrect. Overall, 27 percent of unrealized financial additionality claims and 12 percent of unrealized nonfinancial additionality claims were found at evaluation to have been inaccurate.

IEG’s analysis indicates that this type of error is diminishing in frequency in more recent projects as up-front analysis has strengthened. IEG compared a sample of 15 projects claiming financial structure additionality that had been approved before 2018 with a parallel sample approved between 2018 and 2021. In the older cohort, only one-third of projects offered a specific reference to country market conditions to justify their claims of additionality. In the more recent cohort, 80 percent of projects did so, and since FY20, the sample suggests that all projects have done so. This trend indicates that analysis to provide evidence that IFC is offering better than market terms has become routine (box 4.1). In recent years, the Global Macro and Market Research team has offered analysis of prevailing market terms for financing to support financial additionality claims.

A second problem at appraisal is when additionality is claimed for planned support that is later found not to have been delivered. This problem is especially common for nonfinancial additionalities such as standard setting and knowledge sharing additionality. This can happen either within a project or where a claim of additionality is made based on an anticipated subsequent AS project. An example is IFC’s support for a Costa Rican housing society; it was approved as an integrated IS-AS project, but the AS was not delivered.

IFC anticipated using AS to support nonfinancial additionality in 25 percent of investment projects but realized it in only 14 percent. The knowledge, innovation, and capacity-building additionality subtype relies more on the use of AS projects than the standard-setting additionality subtype (33 percent and 8 percent of projects, respectively). It is, therefore, more affected by the lack of delivery of AS. A variety of factors may influence the ultimate delivery of AS, including client commitment and resources, but the ability to accurately identify additionality and its delivery mechanism is an issue of work quality.

Box 4.1. Example of a Good-Practice Claim of Financing Structure Additionality

In one project, the International Finance Corporation is providing a long-term financing package, including blended finance, with an overall tenor of 19 years and a 46-month grace period. These terms improve the viability of the project by matching the long-term nature of revenue streams to debt service obligations while maintaining a competitive tariff. These financing terms are not available on the local market. Market data show that no international project finance in the local power sector had been provided over the previous 5 years. Over the previous 12 months, there was only one euro-denominated syndicated loan provided to a corporate in the country, benefiting the services sector, with a tenor of 7 years. There were no US dollar–denominated corporate bonds issued in the country over the previous 12 months.

Source: International Finance Corporation project document, anonymized to protect confidential information.

Good project supervision is associated with better additionality outcomes, especially regarding nonfinancial additionality. Because much nonfinancial additionality is realized over the life of a project, monitoring and supervision are essential to ensure its realization. Where IFC follow-up is lacking, the realization of additionality can suffer. An evaluation of IFC’s support for a telecommunication service company in Nigeria found that IFC did not follow up with the client on its plan for the client to implement an integrated E&S management system. In the case of a Brazilian telecommunications company, IFC failed to deliver on knowledge, innovation, and capacity-building additionality. The project evaluation determined that IFC had no direct contact with on-site management and staff after its investment, instead handling supervision from Washington, DC. It found that more intensive supervision by IFC’s technical specialist might have helped in diagnosing management and operational problems and achieving a better outcome.

Staff Capabilities

Staff expertise, experience, and presence in the field are key to IFC’s delivery of additionality. In case studies, IFC’s most successful sector engagements typically involved a combination of in-the-field capability and global industry expertise that could be mobilized as needed (table 4.2). Case studies also found that these were key IFC advantages in delivering industry and environmental, social, and governance knowledge. In IEG’s expert interviews, 60 percent of respondents expressed the view that IFC’s combination of local and global expertise was a key source of additionality. IFC brought its global experience to bear in Mexican independent power provision; renewable energy provision in Egypt and South Africa; microfinance in Bangladesh, China, and Nigeria; and green financing in Colombia and South Africa (see box 4.2 about Colombia). Clients appreciated IFC’s ability to combine in-country expertise with international industry experts. In South African renewable energy, this combination enabled an early concentrating solar power project. In Bangladesh microfinance, a client praised IFC’s in-house expertise, “No one knows the market like IFC.” In addition, in Bangladesh, the ministry of finance praised IFC’s role in sharing knowledge and capacity building as “pivotal.” In China microfinance, much of IFC’s expertise was locally based and easily accessible by clients, potential clients, and the government. Its in-house expertise extended to its policy advocacy and support function. Further, IFC’s global knowledge was a major asset as digital finance came to the forefront in China.

Table 4.2. Country Case Study Evidence on Positive and Negative Factors Associated with Realization of International Finance Corporation Additionality

|

Country |

Safeguards and Due Diligence |

Staff Capabilities, Knowledge, and Long-Term Presence in the Field |

Upstream Early Sector Work |

Monitoring and Reporting Additionality |

World Bank Group and DFI Collaboration |

Client Capacity and Commitment |

Policy and Political Environment |

|

Bangladesh |

+ |

+ |

+/− |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

|

China |

n.a. |

+ |

+ |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

|

Colombia |

+/− |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

+ |

n.a. |

|

Egypt, Arab Rep. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

+ |

+ |

n.a. |

|

Indonesia |

+ |

+ |

+ |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

|

Mexico |

+ |

+ |

n.a. |

n.a. |

+ |

n.a. |

n.a. |

|

Nigeria |

n.a. |

+ |

+ |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

|

South Africa |

n.a. |

+ |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

− |

n.a. |

|

Türkiye |

+/− |

+ |

+ |

n.a. |

+ |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group country case studies.

Note: + indicates evidence of a positive relationship; − indicates evidence of a negative relationship; +/− indicates mixed evidence. DFI = development finance institution; n.a. = not applicable.

Box 4.2. Colombia: From Global Knowledge to Local Green Finance

In Colombia, the International Finance Corporation transferred global knowledge on green building and climate finance—together with financial support—to a local bank. One embodiment of shared knowledge was the International Finance Corporation’s Excellence in Design for Greater Efficiencies green building certification tool. The International Finance Corporation’s support for green financing since 2018 was critical to structure a new operation to support the 2022 issuance of the second Basel III–compliant (B3T2) subordinated bond in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group Colombia country case study.

Internal Procedures

Internal IFC procedures and incentives enhance or constrain the realization of additionality. As noted in chapter 2, several procedures have been introduced since 2018 to support the quality of IFC additionality claims and the evidence behind them during project preparation. The new procedures include investment teams’ interactions with AIMM on additionality. AIMM was cited in half of IEG’s expert interviews as a factor enhancing IFC’s articulation of additionality and rigor at approval. However, several staff members felt that AIMM focused on additionality for which quantitative evidence could be provided to the exclusion of some other forms of additionality, such as innovative financing and mobilization.

Similarly, staff saw IFC’s safeguards and quality reviews as a double-edged sword. The same care and safeguards that could offer the comfort of IFC’s imprimatur of approval impose significant transaction costs. Several interview respondents felt that the sum of IFC’s procedures induced delays and imposed overheads that reduced IFC’s ability to compete. In South Africa, clients noted the need to wait for approvals with IFC, although one client commended the IFC team for getting a project cleared in a time comparable to other financiers, which the client regarded as having required exceptional dedication.

IFC systems for recording, monitoring, and reporting project additionality are incomplete, constraining learning and transparency. Anticipated additionality claims are reviewed for quality and credibility at project approval. According to IFC’s guidelines, once a project is approved, IFC teams are expected to enter additionality information and related additionality milestones and indicators into a new additionality database and provide regular updates and evidence of when and how additionality was delivered during project implementation. Such a system could facilitate supervision and inform learning. However, the envisioned additionality database is not yet operational, and little or no monitoring of additionality is currently being done under the old system (Development Outcome Tracking System). In addition, despite IFC’s guideline stating that “IFC will provide annual reporting on achievement of additionality as part of development impact reporting,” (IFC 2018, 11), it does not do so. Information on additionality is disclosed to the public by project. For each investment approved, IFC discloses a factual summary of the main elements of the investment, including IFC’s expected role and accountability in compliance with IFC’s Access to Information Policy (IFC 2012). Transparency also remains limited and mostly constrained to anticipated additionality in the other MDBs (box 4.3).

At completion, IFC assesses whether additionalities were realized only for a sample of mature projects. Those sampled undergo IFC’s self-evaluation process—the Expanded Project Supervision Report—and IEG’s validation. Projects not selected for self-evaluation generate no information on whether or not anticipated additionality was realized.

Interviews with IFC staff indicated that some internal incentives might mitigate against the realization of additionality. The majority of staff interviewed raised reservations regarding the alignment of staff incentives with additionality. One issue is the lack of explicit recognition. Although anticipating additionality is mandatory, there is neither a reward nor a penalty for realizing additionality because IFC does not track realization. However, there are reportedly strong incentives to deliver projects and volume. Another factor cited was limited resources. For example, investment officers may not have time to carefully or strategically reflect on or support the delivery of additionality if they are under time pressure to meet targets.

Box 4.3. Multilateral Development Banks’ Published Information on Project-Level Additionality

Multilateral development banks’ transparency about project additionality has improved after recent system upgrades, although it remains shallow and mostly focused on anticipated additionality.

- The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development publishes brief details on additionality in its project summary documents, usually identifying three sources.

- With the introduction of its Additionality and Impact Measurement system, the European Investment Bank now discloses some information on additionality and impact in its project summary sheets but with limited detail or separation of the two elements and no rating.

- For several years, the African Development Bank has produced a section on complementarity and additionality in its project summary notes. Details vary from project to project, but it is sometimes quite informative about additionality.

- The Asian Development Bank produces no summary but, in limited cases, has released a redacted version of its board project document with a section on value added. This section identifies elements of financial and nonfinancial additionality in some cases, but the treatment varies widely.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group deep dive (see appendix F).

Project-Level External Factors

Several external factors also have a critical influence on realizing additionality. They include client capacity and commitment, the political and policy environment, and competition and collaboration with other financiers.

Client Capacity and Commitment

Client capacity and commitment are important factors in realizing additionality. Given that many additionalities (especially nonfinancial additionalities) are based on clients changing their behavior (for example, adopting new practices and standards), clients’ willingness and capability to follow through are key. Thus, IFC’s selection of clients can determine whether the clients accept IFC’s advice and guidance on improving their businesses. As noted, one reason planned AS is not always delivered is a lack of client commitment and capacity. Several IFC experts interviewed see client capacity as constraining IFC’s realization of additionality.

Project evaluations often cite a lack of client commitment and capacity as a reason for failures to realize additionality. For a tourism client, IFC did not realize the anticipated E&S additionality in part because of a lack of client understanding and capacity. A financial sector client in Latin America ultimately rejected a planned advisory project intended to deliver knowledge and capacity on risk management for its smaller borrowers. A financial services group client rebuffed IFC’s efforts to get it to abide by IFC’s financial covenants promoting better banking practices to manage risk.

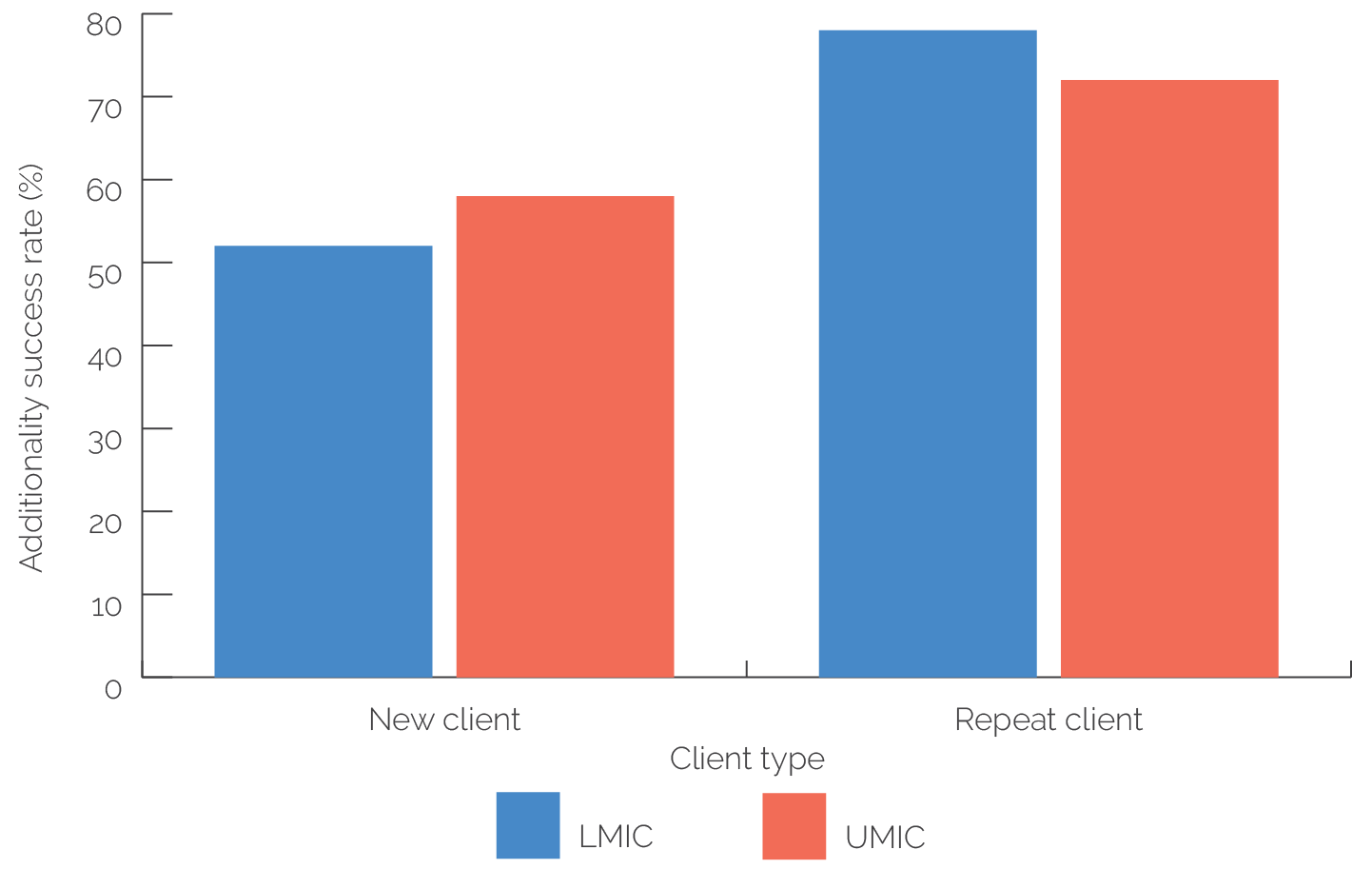

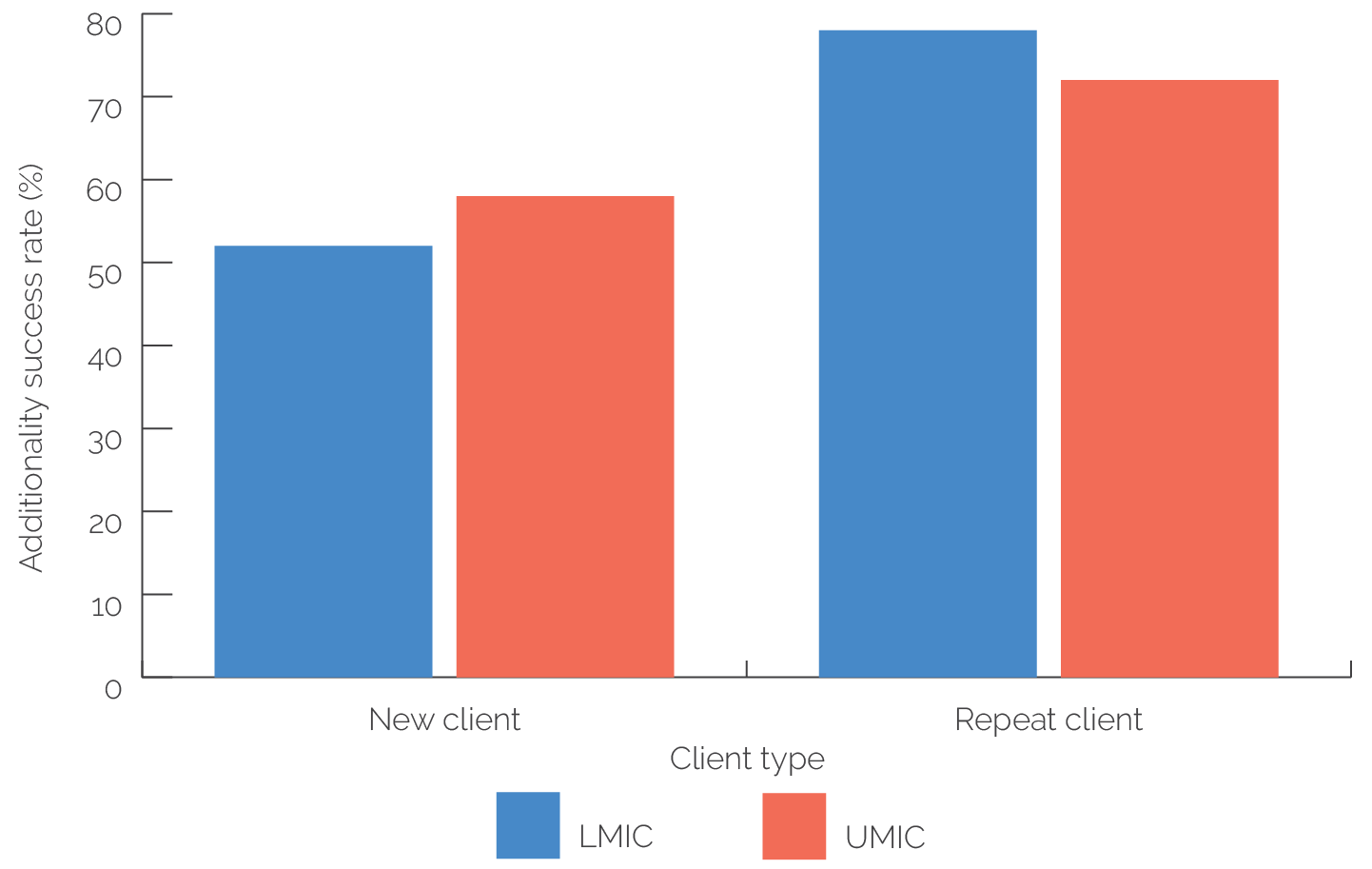

Figure 4.1. International Finance Corporation Additionality Success Rate by Client Type and Country Income Classification

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis of evaluated projects.

Note: LMIC = lower-middle-income country; UMIC = upper-middle-income country.

Furthermore, good clients often turn into repeat clients, and IFC’s additionality (particularly nonfinancial additionality) is higher with repeat clients than with new ones (figure 4.1). The benefit of being a repeat client is less in UMICs, perhaps because new clients start from a higher capacity than in LMICs. However, the benefit that being a repeat client has on the realization of additionality appears magnified in LMICs. This advantage for repeat clients in realizing additionality in LMICs suggests either strong selectivity of repeat clients for those with commitment and capacity or strong success in building commitment and capacity among new LMIC clients.

A Supportive Political and Policy Environment

A supportive policy, regulatory, and political environment is vital for IFC to realize additionality. Where policy makers and regulators are open to input from the Bank Group, there are opportunities for IFC to engage upstream or work through the Bank Group for upstream sectoral reforms beneficial to private sector participation. One example is in Colombia, where IFC worked with regulators on a framework for green finance. In the Bangladesh power sector, the World Bank had a long-standing technical assistance and capacity-building relationship with power sector regulators. In some instances where the existing policy framework is weak, IFC’s contribution can be stronger if local authorities are open to reform. For example, the realization of E&S additionality is inversely correlated with the local E&S legal framework and is more common in LMICs than in UMICs. Where the existing E&S regulatory framework is excellent (strong and well enforced), we may not see much IFC additionality on E&S.

Where local authorities are not open to favorable policies, IFC’s potential additionality may be constrained. In Indonesia, Mexico (power), Nigeria (microfinance), and South Africa (power), policies enforced during FY11–21 worked against private sector solutions (see box 4.4 about Indonesia). Such policies constrained opportunities for IFC to add its distinctive value.

Box 4.4. Indonesia’s Turn toward State-Owned Enterprises

Since 2014, the Indonesian government has relied more on public sector enterprises to drive economic growth. The emphasis on state-owned enterprises makes it difficult for the International Finance Corporation (IFC) to add value. IFC staff members note that the typical roles in other countries where IFC can add value are in large projects with the private sector that combine financial and nonfinancial additionality, especially in infrastructure. In such cases, IFC can offer industry-leading expertise to develop infrastructure projects that provide essential services while ensuring that environmental and social standards are met. In infrastructure, advisory services are a crucial component, and IFC can advise governments and support sector reforms that can translate into private investment for priority projects and sectors. IFC also offers its deep experience in providing financing and structuring solutions for sustainable infrastructure projects in developing countries, offering a range of financing and risk products tailored to meet project needs. The products include loans, equity, quasi-equity, currency swaps, and local currency products, along with World Bank and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency guarantees and insurance and mobilization of funding through IFC’s syndication programs and work with IFC’s Asset Management Company to engage with institutional investors. However, despite a tremendous need for national and municipal infrastructure, because of the government of Indonesia’s reliance on state-owned enterprises for infrastructure, IFC is unable to engage in a significant way in this sector.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group Indonesia case study.

Competition and Collaboration with Other Financiers

The presence of other sources of development finance and support can afford fertile ground for collaboration but may also induce competition where the flow of bankable deals is limited or private finance is abundant. In cases where IFC was well established in a country or sector or a first mover, it often mobilized financing or support from other DFIs, magnifying its additionality and impact through collaboration. Financing large investments (especially in infrastructure)—which may exceed the capacity or exposure limits of a single institution for a single investment, client, or country—can motivate DFIs to collaborate through co-investment. IEG found multiple examples of IFC partnering with EBRD and IDB, including a variety of other bilateral and multilateral donors, in case study sectors. DFIs often share a number of common goals in a country and sector, so they can augment each other’s benefits and influence. In its early engagements in Turkish power generation, IFC often brought in EBRD as a partner. In Egypt’s renewable energy sector, EBRD was also a collaborator on a major wind power project. In Mexico power generation, IFC often brought in IDB investment. IFC itself was sometimes brought in by another international financial institution to cofinance.1 When IFC engaged early in private renewable power generation in South Africa, it brought in a sponsor it had worked with in another region and an investor.

Competition among DFIs is more common where the pipeline of “bankable” projects and reliable sponsors is limited or where opportunities are limited by a well-developed commercial finance market. IFC staff noted instances where other DFIs offered similar financing and competed on terms of financing or cost of services and were sometimes able to reduce the cost of lending or offer free AS to gain an advantage. As noted in chapter 3, in its case studies, IEG did not find IFC competing with other DFIs on the basis of pricing of its financial products but did hear of other DFIs that were able to offer better pricing on some deals.

Competition may enhance additionality for some clients, but scarcity of projects may also lead DFIs to projects where they offer lower additionality and risk crowding out private financiers. The Multilateral Development Banks’ Harmonized Framework for Additionality in Private Sector Operations states that MDBs should avoid competing with each other and that, when assessing additionality, they should seek to jointly contribute to the success of a project by relying on their respective core strengths rather competing or duplicating efforts (AfDB et al. 2018). Yet, clients may appreciate such competition. Sophisticated clients are assessing the advantages and complementarities of DFI financing on their own. In the case of a large commercial bank in Africa, the client knew well the different financial features of each DFI and used one, the other, or several of them depending on its financial needs. A large bank in Europe and Central Asia reportedly worked with an array of different DFIs (including IFC) and private financiers, considering their terms, investment capacity, and sectoral capabilities. In such cases, it may be appropriate to question the degree of additionality, given that the alternative to IFC engagement (the counterfactual) would be a project proceeding with a different source of finance.

IFC often engages in particular markets early in their development, but as markets mature and the risks and rewards are better understood, first mover advantages dissipate, and former financing partners (whether public or private) may emerge as competitors. Staff cited instances in which EBRD was able to offer free technical assistance to accompany its financing and others in which IDB Invest could offer less expensive local currency financing than IFC could offer. In fact, about half of IFC experts interviewed viewed competition with other financiers as a constraint on IFC’s additionality. For example, in the Turkish power generation market, EBRD transitioned from a frequent partner to a frequent competitor. Where such competition is shaped by the availability of private finance, care is required to ensure that IFC (and other DFIs) are providing additionality and not crowding out private finance.

Additionality beyond the Project

Some additional internal factors and most of the external factors already identified have implications for additionality that go beyond the project level, pointing to the value of thinking in terms of country sector. IFC’s additionality framework and related internal systems were conceived to capture additionality at the project level. Thus, they do not systematically capture additionality beyond the project level, and IFC does not envision them doing so.

Taking a wider perspective could reveal important additionality factors at the sector and country levels. IFC’s distinctive benefit to a country or sector usually builds over a long period through a combination of sequenced interventions, policy dialogue, cooperation with other DFIs, interactions with stakeholders, and similar work. The absence of systematic ways to capture additionality beyond the project misses opportunities for learning and shaping strategy. It also omits important parts of the story about IFC’s additionality. In the remainder of this section, we describe success factors for achieving additionality beyond the project.

Long-Term Presence and Engagement

IFC’s long-term presence and engagement in country sectors emerged from several countries as a critical source of additionality. Long-term presence afforded not only knowledge of the market and potential clients but also the flexibility to respond quickly to changing conditions and priorities in circumstances where IFC’s global knowledge and local knowledge gave it a unique ability to add value. In one East Asian country, IFC’s long-standing relationships with national authorities helped it take an active and adaptive approach. This approach helped create the legal and regulatory framework for the establishment of the microfinance industry through a sequenced combination of upstream, downstream, investment, and advisory interventions. In Nigeria, faced with a restrictive authorizing environment and weak local capacity in microfinance, IFC required a long-term presence and engagement to realize some of its nonfinancial additionality through enhancing elements of the enabling environment by capacity building of financial institutions and sector reform.

Strategic Planning Tailored to the Context

Coinciding with long-term engagement is the element of strategic planning tailored for engagement in the sector in a specific country context. As noted in prior chapters, IFC can have a larger development effect in sectors where it can engage early in market development; apply multiple instruments in a sequential or complementary manner; collaborate with Bank Group institutions or other DFIs, financiers, and sponsors; and work both upstream and downstream. IFC realizes beyond-the-project additionalities through projects that build on or complement each other and its ability to take on, in aggregate, the financing of larger-scale activities. Examples discussed in chapter 3 include green finance in Colombia, microfinance in China, renewable energy in Egypt, and independent power generation in Mexico (until certain policy reversals) and Bangladesh. For example, at one point in the evaluation period, IFC-financed power generation in Bangladesh amounted to 20 percent of the total supply. In some of these engagements, as the market developed and evolved, so did IFC support. One example is the shift from more traditional microfinance models to digital financial service models. In several markets, as IFC achieved a demonstration effect in one model and others came in to replicate it, IFC moved on to new models and challenges. For example, in Mexico, IFC moved from supporting conventional independent power providers to supporting renewable energy independent power providers. In market creation, as regulators and clients grow in sophistication, additionality derives from moving toward the frontier of technologies and financing.

World Bank Group Collaboration

Collaboration with the World Bank and MIGA offers an opportunity for IFC to enhance its additionality to clients and its impact on sectors, but it is uncommon. IFC 3.0 poses a coordinated, sequential cascade approach as a model for the interaction of Bank Group institutions. This approach is intended to enhance IFC’s additionality and impact and functions largely at the sector level. In particular, it envisions IFC leveraging the World Bank’s policy and institutional capabilities for upstream work and MIGA’s ability to provide noncommercial risk insurance. In some of the examples above, it worked.

There have been cases where IFC and the World Bank (and occasionally MIGA) have collaborated after the model articulated in the cascade. In such instances, the World Bank often takes an upstream role, whereas IFC focuses on financial and advisory inputs to clients, and MIGA at times provides noncommercial risk guarantees. Where this occurred, IEG’s portfolio review indicates that IFC’s additionality was enhanced, for example, in the subtypes of additionality relating to the policy and regulatory framework, mobilization, and noncommercial risk mitigation.

However, such explicit coordination at the sector and project level is not common, except in power generation. In Türkiye’s energy sector, IFC activity deliberately complemented World Bank upstream sector work to establish a regulatory framework for independent power provision, proving to foreign investors that properly structured, private projects in the power sector could be financially attractive investments. IFC also aimed with its early investments to test the new regulations. Without the World Bank, IFC could not have provided such additionality on catalyzing policy and regulatory change. In Bangladesh, the International Development Association, IFC, and MIGA were able to work together in supporting new gas-fired power generation capacity, with substantial benefits for mobilization and commercial risk mitigation. In Egypt, this coordination was evident in support of a large solar energy project, described in the Realizing Additionality beyond the Project section in chapter 3. In South Africa’s power sector, a model of collaboration has emerged quite recently in which IFC identification of sector constraints to private provision informed World Bank policy dialogue, which, in turn, created opportunities for IFC additionality in subsequent projects.

IEG saw in the case studies at least four types of relationships:

1.Coordinated activity—seen in the Egypt and Bangladesh energy sectors.

2.Complementary activity—seen in China microfinance where World Bank analytics and policy dialogue complemented IFC’s long sectoral engagement; also seen where MIGA provided complementary guarantees for multiple IFC power projects.

3.Lack of coordination—in multiple sectors, the World Bank and IFC simply seemed to operate independently, communicating primarily at the time of the CPF. For example, in the case of Nigeria’s microfinance sector, IFC did not coordinate with the World Bank to change the restrictive policy environment.

4.Working at cross purposes—in Indonesia, the view of IFC was that the World Bank’s policy-based lending enabled the government’s embrace of state-owned enterprises. A similar view emerged in the Mexican power sector when the government turned away from reliance on independent private power providers.

Bank Group collaboration and dialogue could be increased and to some extent have been. IEG found in its case studies that collaboration varies markedly by country. Although some contributing factors to collaboration were identified (for example, co-location, need for upstream reform, country conditions, country engagement processes), an important explanatory factor still seemed to be the personalities of potential World Bank, IFC, and MIGA collaborators. Beliefs matter: IFC experts interviewed by IEG rarely embraced the cascade as a pathway to strengthening additionality. Only 15 percent identified engagement with the World Bank as a key means of achieving additionality.

Although case studies found no “silver bullet” to stimulating coordination to enhance IFC additionality, staff collaborative behavior appears to play a substantial role in shaping approaches, as do procedures that increasingly mandate a degree of joint planning. In China, coordination was stronger because of the orientation of IFC country leadership. Joint planning may also play a role. IEG also found that some IFC country strategies’ scenarios (“if-then”) rely heavily on precedent policy and regulatory actions that the World Bank could influence to reach a scenario where IFC engagement substantially expands, indicating that coordinated action could expand opportunities for IFC additionality. For example, IFC’s Indonesia country strategy envisions both substantial policy reform and sectoral collaboration with the World Bank as part of its higher case scenarios. The evolution of the country engagement model, according to which IFC’s country strategy is an input to the Bank Group’s CPF, expands the opportunity for consideration of complementary and collaborative opportunities.

Regional or global programs and partnerships can enhance IFC’s ability to add value and may have broader value added at the regional or global level. IEG saw examples of this in a number of areas where IFC has regional or global initiatives, including climate (green) finance in the Colombia and Türkiye case studies, microfinance in China and Nigeria, gender finance in multiple countries (including support from the Women Entrepreneurs Finance Initiative), capital markets development (with support from the Joint Capital Market Program of the World Bank and IFC), and trade finance (with support from the Global Trade Finance Program and the Global Trade Liquidity Program).

External Factors

Finally, each of the previously discussed external factors influences additionality not only at the project level but also at the country or sector level. Committed clients can be thought of not only in the context of individual transactions but also in terms of streams of interaction. As noted, on average, repeat clients yield stronger additionality, especially in LMICs. (Some strong clients become important sponsors or investors in other countries.) Working to achieve a supportive political and policy environment may not be practical in a single project. However, by means of engagement over the long term and through multiple instruments and partners, it becomes possible to realize additionality on policy and regulatory frameworks to enhance conditions for private sector participation. Finally, collaboration with other financiers may be more likely where there is a shared vision for the sector. This, too, requires a beyond-the-project perspective that can realize higher-level additionality.

- There are also cases where the Inter-American Development Bank mobilized IFC investment for a project, but those would not be claimed by the IFC or validated by the IEG as IFC mobilization additionality.