International Finance Corporation Additionality in Middle-Income Countries

Chapter 3 | Effectiveness

Highlights

Some 96 percent of International Finance Corporation (IFC) investment projects realize some additionality, but many realize only part of the additionality anticipated. Although 82 percent of projects anticipate both financial and nonfinancial additionality, only 60 percent realize both. The overall additionality realization rates in lower-middle-income countries (61 percent) and upper-middle-income countries (63 percent) are very similar.

IFC is less successful at realizing nonfinancial additionality than at realizing financial additionality. Although 87 percent of anticipated financial additionalities were realized, only 63 percent of anticipated nonfinancial additionalities were realized. Because financial additionality is usually built into the design of IFC’s financing, it is often realized as soon as the financing is disbursed. In contrast, nonfinancial additionality is usually realized over time and often requires planning and continuing engagement.

Some additionality subtypes, such as standard setting and noncommercial risk mitigation, are realized in many projects where they were not anticipated. It is unclear why this happens.

Financing structure additionality is the most common type of financial additionality, whereas standard setting is the most common type of realized additionality. In 83 percent of cases, standard-setting additionality relates to environmental and social standards. IFC is a leader among development finance institutions in its ability and willingness to monitor and enforce compliance with environmental and social standards, which often requires intensive, sustained client interaction. Advisory services are a key instrument for nonfinancial additionality and are used more commonly in lower-middle-income countries than in upper-middle-income countries. Yet, advisory services are realized for only 57 percent of investment projects that anticipate them.

Realizing additionality is positively associated with both project development outcomes and project investment outcomes. Of projects with a high additionality rating, 74 percent have a successful development outcome. Further, 81 percent of projects with a low additionality rating have a low development outcome rating. Realizing nonfinancial additionality is particularly important for development outcomes.

IFC treats additionality primarily at the project level, but the country and sector lenses afford a potentially valuable additional perspective. Focusing strictly on projects can miss opportunities to realize greater additionality for clients, sectors, and countries. Thinking about additionality arising from sequenced or complementary activities may expand the identification of opportunities for IFC to tap into regional or global programs and partnerships or to increase collaboration across the World Bank Group and with other development finance institutions.

This chapter addresses the effectiveness of IFC additionality. In alignment with evaluation question 2, we first examine the extent to which IFC realized anticipated financial and nonfinancial additionality in MICs (including LMICs and UMICs) during the implementation period. We assess this by looking at whether projects received a successful (“above the line”) rating in IEG’s subsequent project evaluations.1 Second, we assess the extent to which the financial and nonfinancial additionality IFC is realizing is plausibly associated with enhanced outcome measures including development outcome. Finally, we apply the country sector lens to learn about where and when IFC’s overall activities in a country sector may add up to something greater than the value added by each individual project.

Realizing Project Additionality

IFC almost always realizes some project additionality. IFC realized at least one type of additionality—financial or nonfinancial—in 96 percent of its evaluated investment projects. Financing structure (for financial additionality) and standard setting, noncommercial risk mitigation, and knowledge, innovation, and capacity building (for nonfinancial additionality) are the most frequently realized subtypes of additionality.

Realized project additionality often falls short of what is anticipated. Of 579 evaluated IS projects, IEG rated 62 percent successful (“above the line”) in additionality. The majority of projects anticipate more than one type of additionality; however, many do not realize all the additionalities anticipated. For example, 82 percent of projects anticipate both financial and nonfinancial additionality, but only 60 percent deliver on both.2 The overall additionality success rates in LMICs (61 percent) and UMICs (63 percent) are very similar.

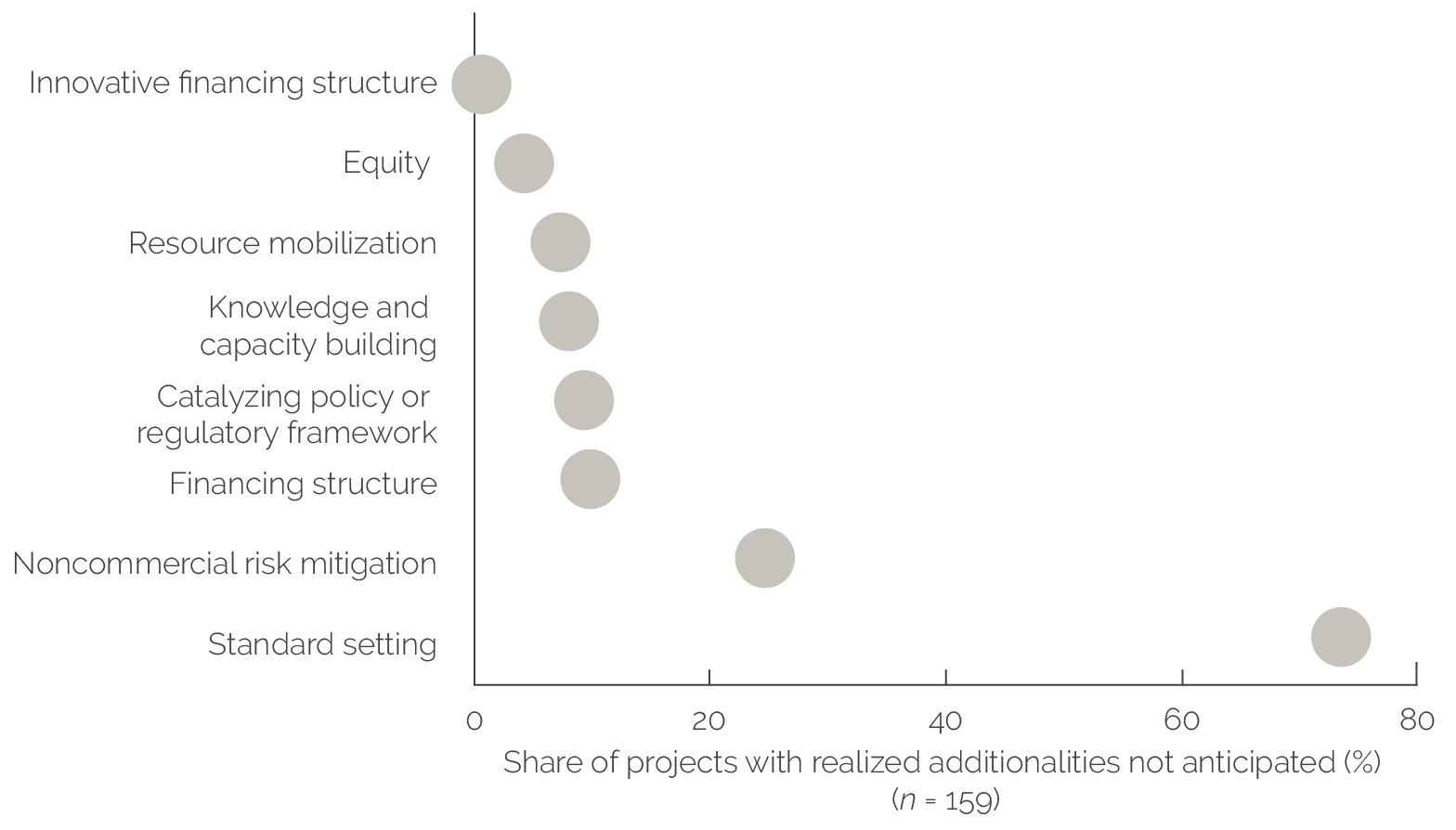

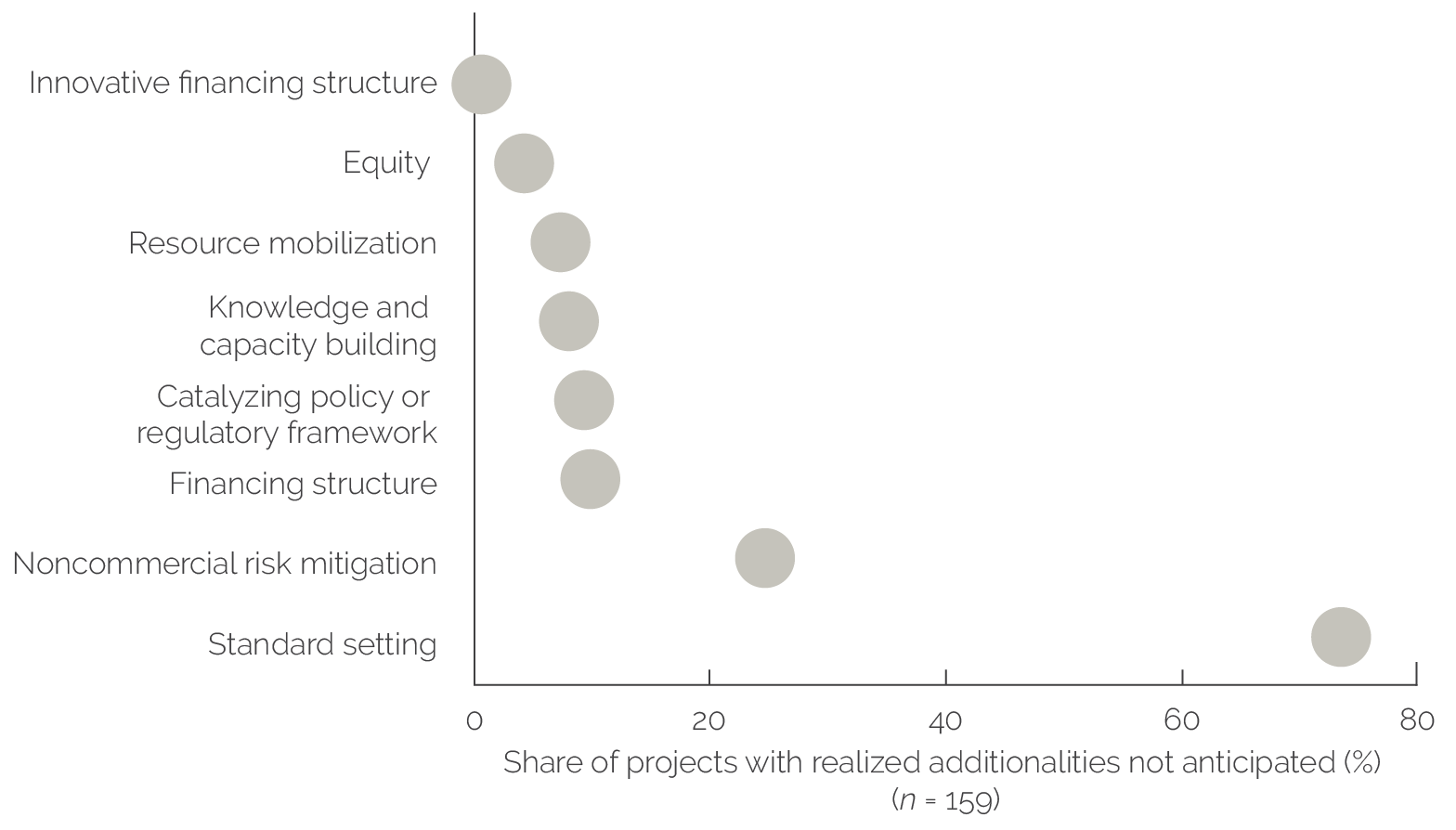

Two additionality subtypes are realized in many projects where they were not anticipated: standard setting and noncommercial risk mitigation (figure 3.1). IFC generally requires some compliance standards, which may bring standard-setting additionality to projects where it is not claimed as an explicit project feature. IEG’s review of evaluated projects indicates that this is exceptionally common—observed in 102 evaluated projects. Similarly, IFC’s presence may comfort investors even where it is not explicitly anticipated as an additionality. For example, noncommercial risk mitigation was realized but unanticipated in 33 projects. It is unclear whether these additionalities are difficult to anticipate or, alternatively, difficult to document with quantitative evidence and, therefore, not claimed in project appraisal.

Figure 3.1. Projects with Additionality Realized but Not Anticipated

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Data are based on portfolio analysis of 579 evaluated projects with complete documentation.

Financial Additionality

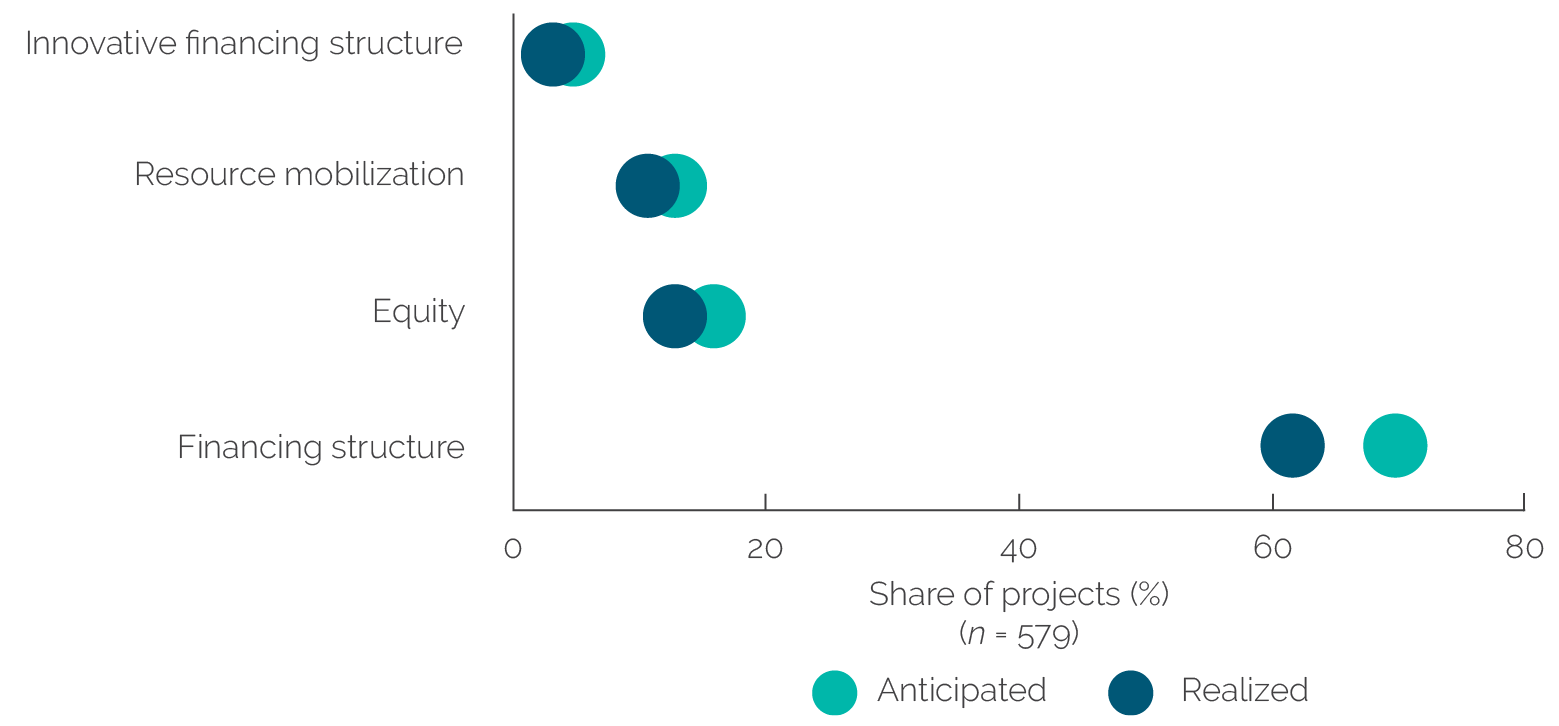

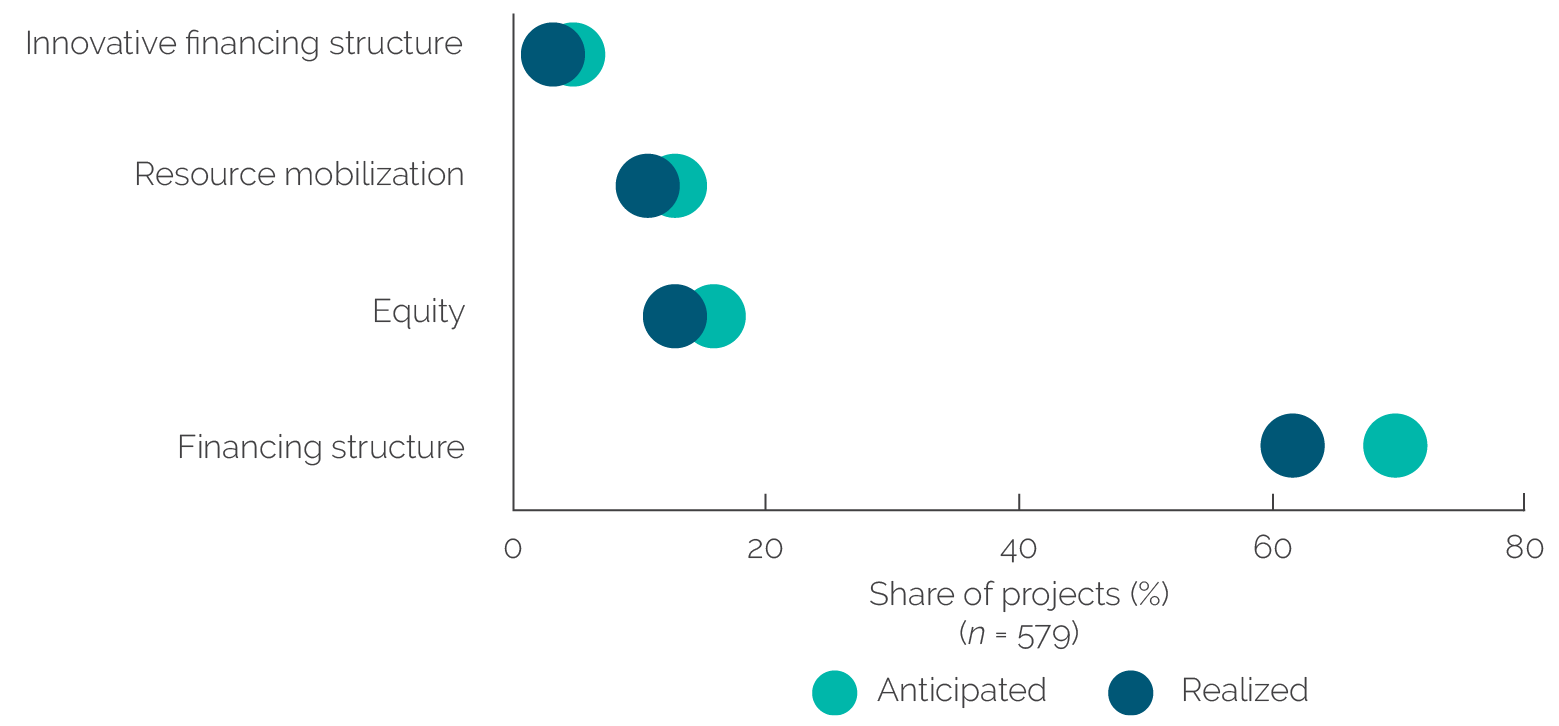

IFC is generally successful in realizing financial additionality. Overall, 86.7 percent of financial additionalities were realized (figure 3.2). Financial additionality is usually built into the design of IFC’s financing in a project. Hence, in its two most common forms, it is realized as soon as the financing is disbursed. By subtype, financing structure additionality is by far the most frequently anticipated and realized, followed by equity, then resource mobilization, and finally innovative financing structure.

Figure 3.2. Comparison of Anticipated and Realized Financial Additionality

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio analysis of International Finance Corporation projects evaluated in 2011–21.

Financing structure additionality (through the amount, tenor, grace period, or provision of local currency financing) is the most common type of financial additionality anticipated. This form of additionality most commonly emphasizes IFC’s ability to offer financing of a longer tenor than the market can provide, which is appealing where it matches loan maturity to an investment activity’s maturity. Financing structure additionality is realized in 62 percent of IFC evaluated projects with a success rate of approximately 89 percent (figure 3.2). Financial additionality based on financing structure is primarily rooted in longer tenors to the exclusion of other subtypes of financing structure additionality (for example, local currency). In Pakistan in 2020, IFC was able to offer a wind power project a 13-year loan that would not have been readily available in the local market. However, in both Nigeria’s microfinance sector and South Africa’s renewable energy sector, IFC was able to offer two features of financial structuring—loans that were of long tenor and in local currency. In several countries, over time, other financiers began offering loans of similar characteristics; hence, it was the availability of long-tenor finance early in the market’s or sector’s development that strengthened IFC’s additionality. During the COVID-19 crisis, banks in several countries became particularly interested in IFC’s long-tenor financing (and liquidity support) as other sources dried up.

Equity (where IFC provides equity that is unavailable in the market in ways that strengthen client financial soundness, creditworthiness, or governance) is the second-most common subtype of financial additionality. It is anticipated in 16 percent of projects and realized in 13 percent of them (81 percent success). In Türkiye, IFC used combinations of equity and loans in the financial and energy sectors, also investing through equity funds. One use of equity was to help banks strengthen regulatory capital. In postconflict Sri Lanka, IFC used an equity investment in local currency to provide a stable source of funding for a bank aiming to expand and promote financial inclusion for poor people and small farmers. In Jamaica, IFC’s $20 million equity investment in a mobile communications firm provided long-tenor growth capital unavailable locally, provided IFC’s seal of approval to attract investors, and opened an opportunity to advise the company on social responsibility and supply chain management. However, in a South Asian company, IFC’s equity investment failed to realize additionality in part as a result of weak screening, and the company ceased operation.

Low interest rates are not a source of financing structure additionality. The evaluation did not find evidence of IFC relying on lower-than-market interest rates as a form of additionality. Because IFC’s additionality framework does not include lower pricing as a form of additionality, none of the projects in the reviewed portfolio present such types of claims (as anticipated or realized additionality). Hence, IEG did not conduct a systematic analysis of IFC’s prices in relation to the prices of other actors (private and DFIs) to assess whether IFC may be crowding out its competitors. IFC staff and stakeholders interviewed for the nine country case studies indicated that IFC competes on product and institutional features rather than on pricing. In addition, some clients and competitors stated that IFC’s products were more expensive than those of other financiers, including of some other DFIs, pointing to no risk of crowding out. Nevertheless, there are certain products, such as concessional blended financing or performance-based incentives (for example, where interest rates are reduced if clients meet certain development targets), in which IFC has the potential of offering lower rates than the market, which in turn has the potential to crowd out competitors. In its case analysis, IEG did not, however, observe concrete examples of this.

IFC anticipated resource mobilization additionality in 12 percent of projects and realized it in 11 percent of them (92 percent success). Resource mobilization is claimed only when IFC had a verifiable active and direct role in mobilizing other investors—for example, a syndication role, as mandated lead arranger or similar role. Anticipated and realized mobilization and additionality reported in the evaluation conform to this definition and are based on project-level validations. In Mexico’s energy sector, in the early days of independent power providers, IFC often brought in the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and sometimes other DFIs, commercial banks, and other financiers. In Egypt, IFC worked with EBRD and the Overseas Private Investment Corporation on a major wind power project, and in the Dominican Republic, IFC mobilized syndicated and parallel loan financing for a wind power project, providing comfort to investors wary of country risk and market volatility.

Financial additionality through innovative financing structure or instruments (including structures not available in the market that add value by lowering the cost of capital or better addressing risks) is anticipated in 4 percent of IFC projects and realized in 3 percent of them. IEG’s interviews suggest that IFC perceives its ability to provide innovative financing structures or products as its greatest source of value added, although their realization appears rare in the evaluated portfolio. Despite IFC’s strategic intention to deliver more innovation in UMICs compared with LMICs, the rate is similar in each.

Several projects in country case studies realized innovative financing structures without anticipating them. For example, in Colombia, IFC supported a repeat client in issuing a green bond—the largest issued at that time in the entire Latin America and the Caribbean Region. The market structure for green bonds was nascent; therefore, the financial innovation was clear. Nevertheless, the anticipated additionality was nonfinancial. IEG’s observation from case studies suggests that such innovations may, at times, be challenging to document with compelling evidence and thus may be underreported. For example, in the Nigerian chemical sector, IFC supported a first-of-its-kind (in Nigeria) privatization transaction, with substantial mobilization of capital from private banks. However, IFC framed the additionality as noncommercial risk mitigation rather than innovative financing.

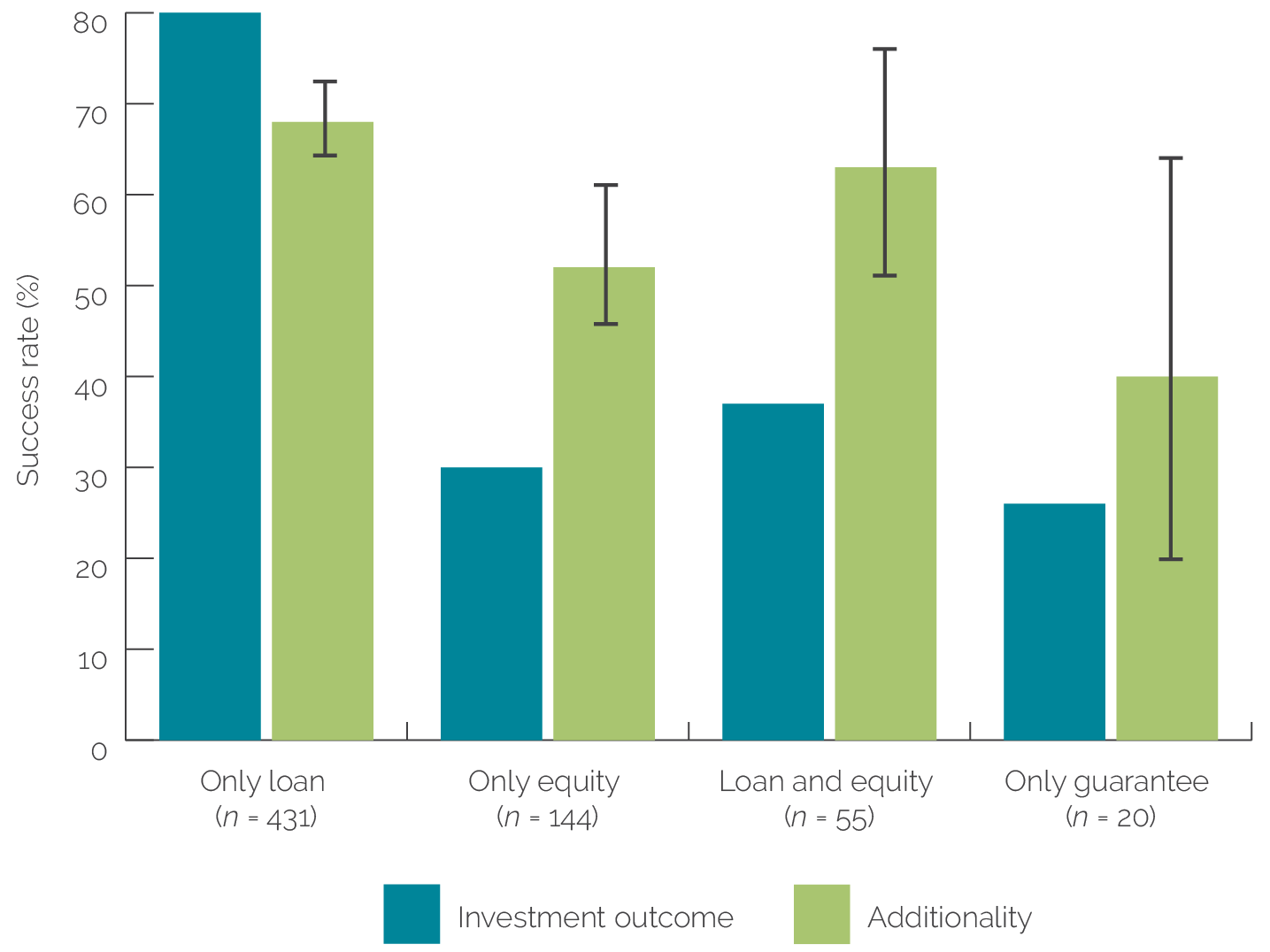

Evaluative data suggest that IFC has different levels of success with different financial instruments (figure 3.3). IFC’s loans are very common and are IFC’s most successful financial instrument, both in terms of realizing project-level additionality and in terms of achieving a positive project-level investment outcome for IFC.3 The record of equity projects is weaker regarding project-level additionality and investment outcome. A combination of loan and equity affords results that fall between those of loans and equity. IFC guarantees are the least successful instrument in terms of both project-level additionality and investment outcome.

Figure 3.3. International Finance Corporation Additionality Success by Financial Instrument

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis of evaluated projects.

Nonfinancial Additionality

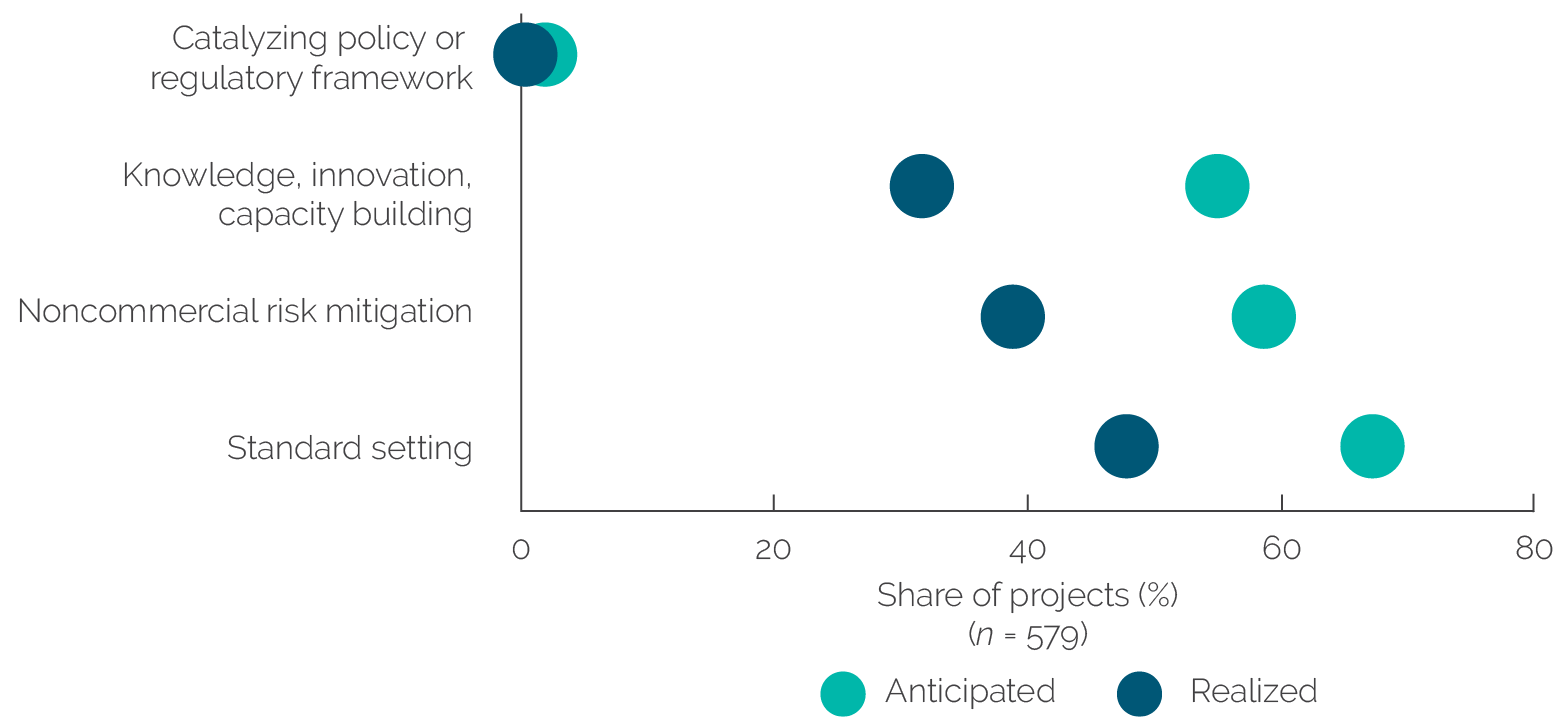

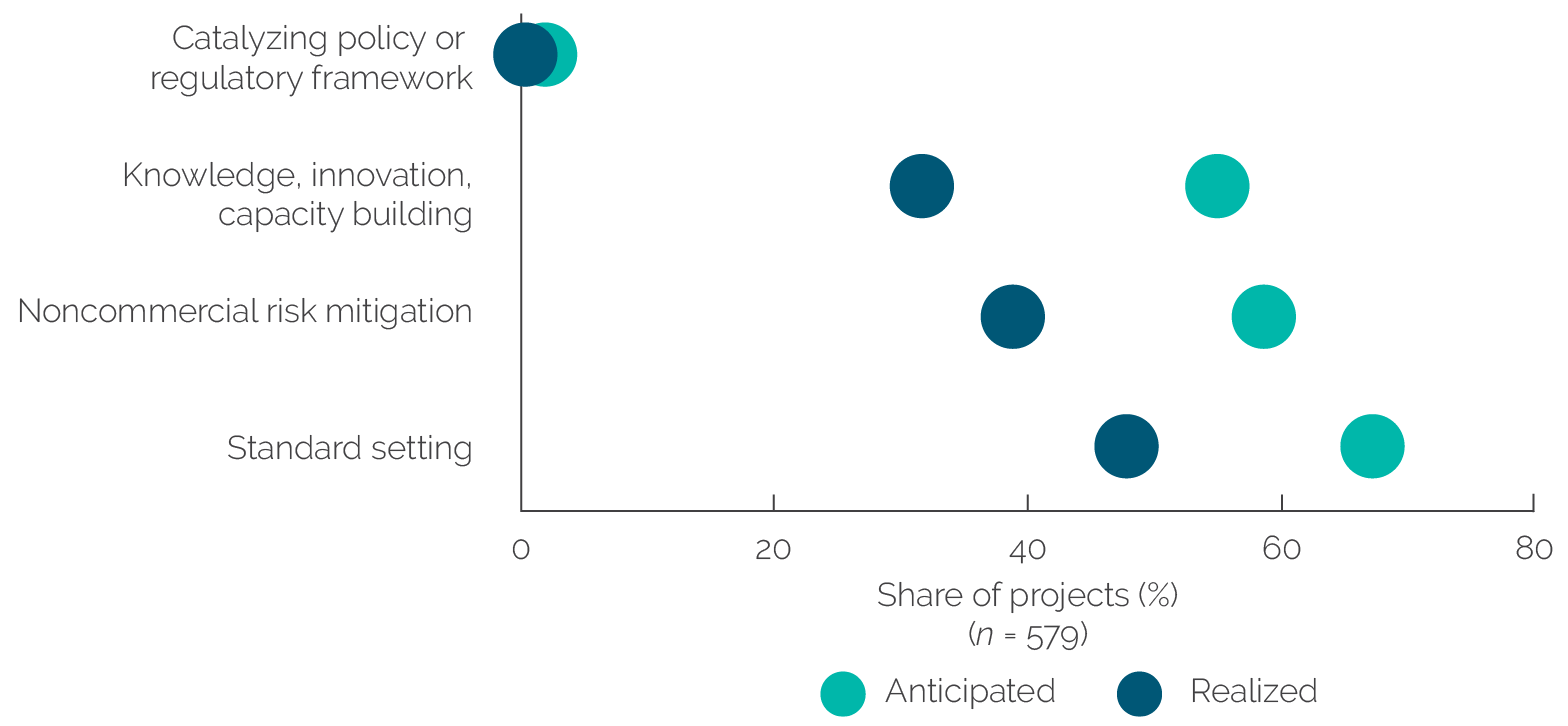

IFC is less successful at realizing nonfinancial additionality than at realizing financial additionality. Only 65 percent of anticipated nonfinancial additionality was realized. In contrast with financial additionality, nonfinancial additionality is usually realized over time rather than at financial disbursement. Thus, it often requires planning, monitoring, and continuing engagement. In fact, the leading reason for IFC not realizing anticipated nonfinancial additionality is its failure to deliver anticipated support, often embodied in AS. By subtype, the realization of additionalities in knowledge, innovation, and capacity building (58 percent realized), noncommercial risk mitigation (66 percent), and standard setting (70 percent) are lower than other nonfinancial types of additionality (figure 3.4). Additionality involving policy or regulatory changes, where IFC involvement in a project catalyzes investment response to a change in the policy or regulatory framework, was found anticipated in only 2 percent of IFC IS projects and realized in 1 percent; hence, it is not detailed in this section.

Figure 3.4. Comparison of Anticipated and Realized Nonfinancial Additionality

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis of evaluated projects.

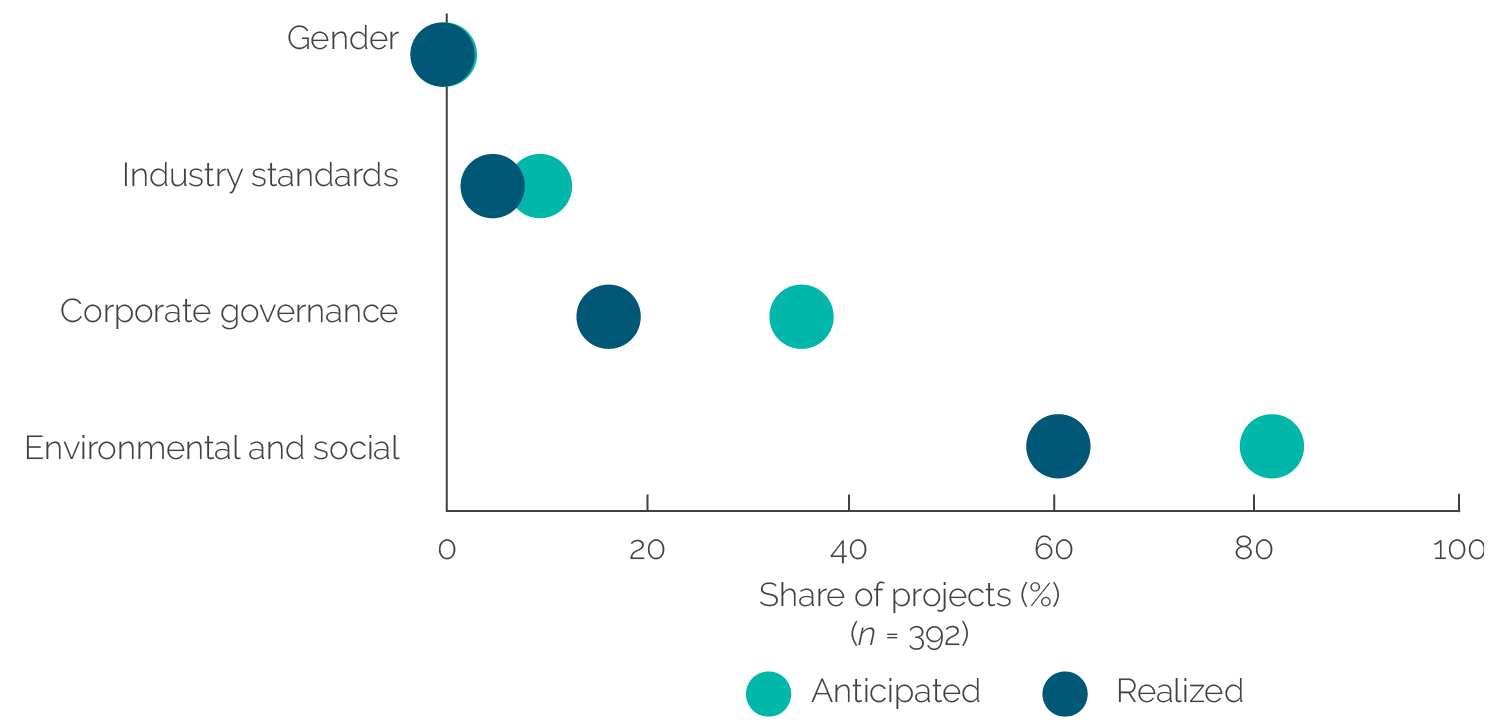

Standard setting, where IFC provides expertise in E&S standards, corporate governance, industry standards, and gender, was the most common form of nonfinancial additionality. Overall, standard-setting additionality was anticipated in 68 percent of projects and realized in 48 percent (figure 3.4). Standard setting relates primarily to E&S standards (anticipated in 83 percent of projects with standard-setting additionality), corporate governance (36 percent), industry standards (11 percent), and gender standards (1 percent; figure 3.5). The objective of standard-setting nonfinancial additionality is to induce changes in client practices in these critical areas.

Figure 3.5. Anticipated and Realized Standard-Setting Additionality, by Subtype

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis of evaluated projects.

IFC is considered a leader among DFIs in its ability and willingness to monitor and enforce compliance with E&S standards. In IEG’s interviews of expert IFC staff, E&S was the second-most commonly identified source of major IFC value added. IFC’s ability to monitor and enforce compliance with E&S standards is a distinctive feature of IFC compared with other DFIs, so IFC is considered a leader. The portfolio review finds that it is realized with a 75 percent success rate. At the same time, as noted previously, IFC often realizes E&S additionality without anticipating it.

Successful realization of E&S additionality often requires monitoring and client “hand-holding,” often yielding superior results. IFC devotes substantial staff and resources to E&S relative to other DFIs, and its compliance monitoring reflects this. In several country case studies, including Colombia, Indonesia, Mexico, and Türkiye, it was clear that IFC invested significant resources in ensuring compliance, giving ongoing attention and interaction between IFC staff and clients. In multiple instances, other DFIs and investors with fewer resources in E&S rely on IFC’s monitoring reports.

Some clients report that compliance with IFC E&S standards makes it easier to attract other international financial institutions and international investors. For example, this benefit was reported by Indonesian domestic businesses breaking into global supply chains. In Colombia, IFC provided a banking client with global climate finance knowledge through AS, transferring know-how in seeking climate finance opportunities. IFC also contributed to building the bank’s capacity in E&S, its ability to use a web-based IFC tool to determine the climate eligibility of transactions, and its ability to monitor and assess its climate portfolio.

Sometimes, despite its efforts, IFC has difficulty getting clients to adopt improved E&S standards and systems. In the case of a Brazilian agri-food firm, IFC ensured that its E&S requirements were incorporated into the project, and during supervision, IFC followed up with the client, convincing it to hire a dedicated corporate manager responsible for E&S issues. However, very little progress was made in reaching the company’s compliance obligations, and the additionality was not realized.

Corporate governance is the second-most common area of standard-setting additionality but is realized only in half the projects where it is anticipated. IFC has rigorous standards for the corporate governance of its clients and helps bring them into conformity with international norms. For example, IFC assisted a client involved in oil and gas pipelines in Colombia by bringing in an international corporate governance specialist to advise it. In China, IFC provided hand-holding assistance on corporate governance to a microfinance nongovernmental organization becoming a commercial entity. AS was structured as an ongoing process of capacity building and knowledge transfer. IFC staff took client executives on a study tour to Cambodia. Later, with IFC’s equity stake, an IFC board member additionally helped build capacity and transfer knowledge on an ongoing basis. However, sometimes IFC’s standards are not adopted by the client—for example, in Mexico, where despite the appointment of IFC’s independent director to a corporate board, IFC’s support did not change the governance structure and practices of the family-owned company. Client commitment and capacity, discussed in detail in chapter 4, are key factors for the realization of standard-setting additionalities.

Explicit standard-setting additionality on industry standards is less frequent and realized in 55 percent of projects where anticipated. IFC often brings international standards knowledge and experts to support client companies. In the case of a Vietnamese agri-food company, IFC food safety advisory worked with the company’s partner farmers to implement food safety standards. In Romania, IFC supported a leading health-care provider in raising standards by delivering services more efficiently and establishing benchmarks. However, in the case of a Nigerian private equity fund, IFC’s advice on international best practice in the structuring of the fund and its ongoing operations, and IFC’s participation on the fund’s advisory board, did not improve fund management or performance.

Noncommercial risk mitigation, where IFC provides comfort to clients and investors by mitigating nonenvironmental, nonsocial, and security risks, such as country, regulatory, project, or political risks, is anticipated in 59 percent of projects but realized in only 39 percent of projects. Clients report valuing IFC’s reputation (which has a risk mitigation effect) and influence (seen as risk mitigating with regulators). In both cases, IFC can add value by reducing risk from noncommercial sources, for example, the perceived risk of political interference or sudden policy changes. In Nigeria, IFC’s presence provided market comfort to international investors and locally grown institutions because they were able to secure funding from various international lenders. In Mexico, in the early days of renewable energy independent power provision, even experienced conglomerates sought IFC’s support to help shield themselves from potentially adverse government decisions. However, in some cases, IFC’s support does not afford the additionality anticipated. In the case of IFC’s support for a Turkish oil and gas services company, IFC’s financing was anticipated to enhance the credibility of the company in the market in support of a planned initial public offering. IFC’s additionality was expected to occur when the company did the initial public offering, but the initial public offering never occurred.

IFC’s ability to add value through knowledge, innovation, and capacity building figures centrally in its value proposition in MICs; however, it has proved challenging to realize this form of additionality. This additionality, where IFC “plays a verifiable, active, and direct role in providing expertise, innovation, knowledge, or capabilities that are material to the project’s development impact because of the perceived weak institutional capacity of the borrower or investee” (World Bank 2022, 3), was identified in 55 percent of IFC IS projects but delivered in only 32 percent. In IEG interviews, IFC experts identified knowledge, innovation, and capacity building far more frequently than any other vehicle for realizing IFC additionality in MICs. IEG found multiple instances in the case studies and portfolio review in which IFC’s global experience and industry experts delivered value to clients while its patient partnership built capacity. In Serbia, IFC augmented the value of its financing to an agribusiness client by guiding financial restructuring, financial reporting, and appropriate insurance policies. In Oman, IFC drew on its global experience to help a bank develop its financing for small and medium enterprises and housing finance.

Yet many projects faced challenges in realizing knowledge, innovation, and capacity-building additionality. In Costa Rica, IFC intended to support a housing finance institution in increasing its reach to low-income borrowers through an integrated investment and advisory approach. The advisory was intended to improve the client’s capacity in risk management and its small and medium enterprises business and strengthen its strategy, sales model, products and services, policies and procedures and tools. However, the advisory project never materialized. In South Africa, IFC planned to support a second-tier South African bank to enhance its capacity in risk management, identify new opportunities, and support energy efficiency and renewable energy. The support delivered, as evaluated, was inadequate, yielding little evident benefit. Chapter 4 explores factors that help explain such missed outcomes.

AS are a key instrument for nonfinancial additionality. A quarter of projects anticipating financial additionality identify AS as a means of delivery.4 This is more common in LMICs than UMICs—37 percent of projects anticipating financial additionality identify AS as a means of delivery. Yet, as chapter 4 discusses, this has proven problematic, in part because in practice in only 57 percent of investment projects with nonfinancial additionality that anticipate complementary AS does the AS actually materialize. When additionalities are to be realized through AS in the financial sector, they achieve a slightly higher success rate (69 percent) than other delivery mechanisms. In real sectors, the use of AS projects is associated with a lower rate of realizing anticipated additionality than other mechanisms for supporting nonfinancial additionality. By contrast, in real sectors, use of a corporate governance or E&S specialist as part of an IS project is associated with a substantially higher rate of success (80 percent) than using AS (54 percent).

Development Outcomes

Realizing additionality is positively associated with both project development outcomes and project investment outcomes. IEG’s analysis of IFC’s evaluated portfolio indicates that 74 percent of projects with a high additionality rating have a successful development outcome, but only 19 percent of projects with a low additionality rating do. Similarly, 77 percent of projects with a high additionality rating have a high investment outcome rating, but only 34 percent of projects with a low additionality rating do. This suggests where IFC can deliver unique support to a client; it generally contributes to overall project success.

Realizing nonfinancial additionality is particularly important for development outcomes. Although IFC has more difficulty realizing nonfinancial than financial additionality, IEG’s econometric analysis suggests that several subtypes of nonfinancial additionality are significantly associated with a higher probability of success in several important outcomes (table 3.1). Projects that realize nonfinancial additionality are 29 percent more likely to have positive social and environmental outcomes. (Projects that realize both financial and nonfinancial additionality are 40 percent more likely to have positive social and environmental outcomes.) For example, when IFC financed a Russian electronic materials manufacturer, it worked with the company to define and implement a platform that brought the company into compliance with IFC’s E&S standards. By project evaluation, the company had established an E&S management system and a human resources policy; was monitoring most key environmental, social, and occupational health and safety parameters; and had a low accident rate.

Specifically, projects realizing knowledge, innovation, and capacity-building additionality are 25 percent more likely to have a positive development outcome rating. Those same projects have a significantly higher likelihood of showing positive project business performance (15 percent more likely), economic sustainability (17 percent more likely), and private sector development (24 percent more likely). For example, IFC supported a microfinance institution in Tunisia in developing a new commercial strategy to expand to new client segments and new financial products oriented toward microenterprises. As a result, by the time of project evaluation, the institution had vastly increased its customer base, reaching over 140,000 new borrowers, 10 times its target.

Table 3.1. Average Marginal Effects for Outcomes Associated with Additionality (percent)

|

Additionality |

Development Outcome |

Project Business Performance |

Economic Sustainability |

Environmental and Social Effects |

Private Sector Development |

|

Nonfinancial additionality |

.. |

.. |

.. |

27.1 |

.. |

|

Financial and nonfinancial additionality |

39.8 |

.. |

.. |

33.4 |

.. |

|

Standard setting |

13.9 |

.. |

.. |

28.0 |

.. |

|

Noncommercial risk mitigation |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

13.8 |

|

Knowledge, innovation, and capacity building |

25.3 |

15.4 |

17.4 |

.. |

23.6 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group econometric analysis of evaluated International Finance Corporation projects, with internal and external control variables.

Note: .. = negligible or insignificant.

Projects realizing the standard-setting subtype of additionality are more likely to have positive development outcome ratings and E&S effects. Projects realizing the standard-setting subtype of additionality are 14 percent more likely to have positive development outcome ratings, and standard setting is associated with a 28 percent higher likelihood of positive E&S effects. For example, in Indonesia, IFC supported a synthetic fiber producer in improving its energy efficiency and resource recovery. By the time of project evaluation, the client company had enhanced its energy efficiency, resource recovery, and clean production, reducing greenhouse gas emissions by more than 10 percent and water usage by more than 20 percent.

Finally, noncommercial risk mitigation is associated with a 14 percent higher probability of positive private sector development outcomes. For example, IFC supported a Palestinian microfinance institution to encourage other international financial institutions to enter the sector, by showing its willingness to take risks the private sector was not yet willing to bear. At evaluation, it was determined that after IFC’s initial loan, both local banks and international institutions became financiers of the microfinance institution.

Realizing Additionality beyond the Project

Although IFC treats additionality primarily at the project level, in several countries and sectors, a country or sector lens affords a more positive view than a project lens. In these cases, additionality creates or builds markets, often through combined upstream and downstream engagement over an extended period. Some of IFC’s biggest value addition occurred when it came into a sector early, stayed, and adapted its support as the market developed.

- In China’s microfinance sector, IFC engaged early and long term, with government and carefully selected clients. It used multiple financing (equity and loans) and AS tools, adapted to specific needs. IFC transferred substantial knowledge to the government and businesses. Its China office supplemented unique in-country expertise with leading global experts mobilized as needed. IFC provided patient capital over 20 years and adapted the type of support over time as the market matured. It worked with carefully selected clients who generally proved to perform well with IFC’s interventions, some of whom became repeat clients. IFC helped build supportive upstream institutions, including regulatory capacity and complementary institutions and a credit bureau and movable asset registry.

- In the Turkish power sector, IFC complemented World Bank support by being among the first investors. The engagement demonstrated that properly structured private power projects could represent feasible and financially attractive investments for foreign investors. IFC’s investments also tested new regulations supported by the World Bank.

- In Bangladesh, the World Bank, IFC, and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) engaged in a coordinated manner to support independent power providers. The World Bank worked upstream on unbundling and improving regulatory capacity. IFC financed independent power providers, some with MIGA guarantees.

- In supporting a large Egyptian solar energy project, the Bank Group coordinated through a programmatic engagement. IFC supplied debt and equity investments, the World Bank provided advisory support to the renewable energy structuring program, and IFC and MIGA mobilized other investors and gave them comfort.

- In Colombia, green energy finance benefited from IFC’s multiple interventions, both upstream and downstream. IFC brought innovation within the Colombian context through the introduction of a green taxonomy for financial sector regulators and the introduction of green bonds downstream through financial sector clients. IFC also led introduction of secondary markets—a way to offer bonds in the over-the-counter market. Multiple stakeholders interviewed for IEG’s case study acknowledged its sector leadership.

In some cases, looking at additionality at the sector and country level raises questions, affording a more negative view than a project view would yield. This can happen where additionalities at the project level do not seem to add up to much at the sector level. In the banking sectors of South Africa and Türkiye, both known for their depth, IFC lending to banks was tiny relative to their assets, and the banks mostly had multiple funding sources. Despite success in delivering at the project level, the unique value added at the sector level was hard to discern.

Where IFC approaches transactions individually, there can be missed opportunities to sequence AS and IS or to collaborate with the World Bank and other DFIs. In such cases, IFC value addition may have been greater with a more coordinated approach. Most of the sectors covered in the case study do not reveal a strong complementarity of AS and IS to obtain a more programmatic benefit for the sector. The China chemicals case study indicated that the sector benefited only at the transaction level, with no greater sector impact. IFC found limited points of entry, working with small-scale clients because larger ones had alternative sources of finance. It entered the sector too late to influence its development and lacked the multi-instrument and upstream engagement it had in the microfinance sector in China. In Nigeria, IFC supported the first privatization in the chemical and fertilizers industry investment, but its additionality was limited to financial structuring and standard-setting benefits to very few clients. During the evaluation period, IFC was not able to scale its engagement or to influence the sector development upstream. In some cases, there can be constraints in the enabling environment limiting IFC’s opportunities to engage beyond isolated projects. This was seen at times during the evaluation period in the banking sector in South Africa and in the renewable energy sector in Bangladesh. In other cases, IFC’s overall presence and program size in a country may not allow multiple engagements.

Similarly, a “beyond the project” perspective can enhance IFC’s ability to take advantage of collaboration and external resources:

- Regional or global programs and partnerships can enhance and extend IFC’s ability to add value and may, in turn, have broader value added at the regional or global level.

- Collaboration with the World Bank can enable and expand additionality at the country and sector level (as discussed in chapter 4).

Collaboration with other DFIs at the project or sector level was associated with successful realization of additionality, especially in undertaking large projects (also discussed in chapter 4).

- In Expanded Project Supervision Reports and Evaluative Notes (EvNotes), projects are rated for additionality on a scale that includes excellent, satisfactory, partly unsatisfactory, and unsatisfactory. Projects receiving the first two ratings are considered “above the line”—that is, successful. Projects receiving the second two ratings are considered “below the line”—that is, unsuccessful.

- Expanded Project Supervision Reports guidance states that, for additionality to be rated satisfactory, both of the following criteria must be met: (i) all important aspects of claimed additionality were borne out or there were unforeseen ways in which the IFC was additional, and (ii) there were no areas where IFC made a negative contribution. Where IFC has not fully realized all aspects of claimed additionality, for a satisfactory rating, the Expanded Project Supervision Report should present evidence as to why the deficiencies are not deemed important in retrospect.

- In terms of loan income or equity returns.

- All figures in this paragraph result from IEG’s analysis of the portfolio of evaluated IFC investment services projects.